1 Introduction

This article starts from the premise that not enough is known about grammatical differences between the standard Englishes of Scotland and England, here referred to as Scottish Standard English (SSE) and Southern British Standard English (SBSE), respectively.Footnote 2 In terms of its grammar, SSE is only theoretically recognised as a Standard variety, while empirical evidence concerning specific grammatical features is scarce. In our study, we focus on a central area of grammar, modal verbs of (strong) obligation.

Twentieth-century developments in the modal verb system of British and American English have collectively been dubbed ‘modal decline’ (e.g. Leech Reference Leech2003, Reference Leech, Marín-Arrese, Carretero, Hita and van der Auwera2013; Smith Reference Smith2003; Leech et al. Reference Leech, Hundt, Mair and Smith2009), which describes a decrease in the frequencies of core modals partly compensated by higher frequencies of semi-modals. Within the semantic domain of strong obligation, for example, the relative frequencies of the verbal predicates need to and have to have increased at the expense of must (see Millar Reference Millar2009: 204, 208–9; Leech Reference Leech, Marín-Arrese, Carretero, Hita and van der Auwera2013). For Scots (and Scottish English), Miller (Reference Miller, Kortmann and Upton2008: 305) claims that obligation is expressed by have to and need to, while must is reserved for epistemic contexts. This and other evidence in the literature suggests that one difference between SSE and SBSE may lie in this domain.

Based on new corpus material from the Scottish component of the International Corpus of English (ICE-SCO) and corresponding texts from ICE-GB (representative of SBSE), we compare the relative frequencies of must, have to, need to and (have) got to.Footnote 3 While the main focus is on intervarietal differences, we include mode of production (written vs spoken), grammatical subject (first, second and third person) and source of obligation (objective vs subjective) as predictors in a multivariate regression analysis.

Among other features, Schützler, Gut & Fuchs (Reference Schützler, Gut, Fuchs, Beal and Hancil2017) regard modal verbs as central to a better description of SSE: with the exception of (rare) double modal constructions, they are not overtly ‘dialectal’ – their characteristic behaviour in specific varieties like SSE is probabilistic and must be described in terms of frequencies, rather than categorical divergence. This view of intervarietal variation is of course commonplace in comparisons of British English (BrE) and American English (AmE) – see, for instance, contributions in Rohdenburg & Schlüter (Reference Rohdenburg and Schlüter2009). However, as we will argue in section 2, linguistic perspectives on SSE have for historico-political reasons been characterised by what Schützler, Gut & Fuchs (Reference Schützler, Gut, Fuchs, Beal and Hancil2017) call the ‘Scots bias’, i.e. the oversight of such probabilistic differences and a focus on more obvious features directly motivated from Scots. Our investigation aims to make first steps in overcoming this situation. The agenda of our article is twofold: (i) we present corpus-based evidence for a better comparison of SBSE and SSE, increasing the visibility of the latter as a variety, and (ii) we contribute methodologies and results to the existing research on English modal verb constructions more generally.

Section 2 is an introduction to SSE and some of the relevant research gaps. Section 3 summarises essential theoretical and empirical research background. In section 4, we formulate our research questions and hypotheses and explain our corpus-linguistic and statistical methodologies. The presentation of results in section 5 is followed by a conclusion and outlook in section 6.

2 Scottish Standard English, the ‘Scots bias’ and ICE-Scotland

Scottish English comprises a continuum ranging from Broad Scots (the vernacular) to SSE (McArthur Reference McArthur, Aitken and McArthur1979: 59; cf. Aitken Reference Aitken, Aitken and McArthur1979: 85). SSE is in principle recognised as a standard variety, but its phonological features tend to be highlighted relative to its grammatical characteristics, as in McClure (Reference McClure and Burchfield1994: 79):

[SSE] is now an autonomous speech form, having the status of one among the many forms of the international English language, and is recognised as an established national standard, throughout the English-speaking world . . . Like other national forms of English, it is characterised to some extent by grammar, vocabulary and idiom, but most obviously by pronunciation.

In keeping with McArthur's (Reference McArthur1987; Reference McArthur1998) notion of a World Standard English, it is natural to expect grammatical differences between standard dialects to be less salient compared to accent features. Similarly, Giegerich (Reference Giegerich1992: 45–6) associates distinctive lexical and grammatical features of Scottish English with Scots, perhaps thinking more in terms of categorical differences, i.e. constructions that exist in SSE but not in SBSE.

McClure (Reference McClure and Burchfield1994: 85) points out that phonetic and phonological characteristics of SSE are obvious, but that too little empirical research has been carried out on other linguistic levels (cf. exceptions discussed in Schützler, Gut & Fuchs Reference Schützler, Gut, Fuchs, Beal and Hancil2017). A similar ‘complaint’ was made much earlier by Aitken (Reference Aitken, Aitken and McArthur1979: 110), and, we would venture, can still be upheld today: beliefs and intuitions concerning the grammatical distinctness of SSE are supported by little empirical evidence. The question framed by McArthur (Reference McArthur, Aitken and McArthur1979: 57) has largely gone unanswered, and can serve as the starting point for our research: ‘What is the relationship between Scottish Standard English and the other national standards, and … how does it relate to its neighbour in southern England …?’

Research on the grammar of Scottish Englishes tends to focus on grammatical and/or lexical phenomena that are part of the inventory of Scots features (hence the ‘Scots bias’ discussed below; cf. Schützler, Gut & Fuchs Reference Schützler, Gut, Fuchs, Beal and Hancil2017). This may partly reflect a subconscious bias: Scotland and England are not only directly adjacent but form a political union. This, in combination with the historically strong position of the Scots language, weakens the position of SSE as a standard.

Schützler, Gut & Fuchs (Reference Schützler, Gut, Fuchs, Beal and Hancil2017: 279) identify a number of interconnected ‘deficits and gaps in research on SSE’: (i) little interest particularly in grammatical features; (ii) a lack of suitable tools and data resources (e.g. corpora); (iii) a lack of research targeting SSE, which leads to (iv) a descriptive deficit regarding SSE in itself; and (v) difficulties in comparing SSE to other standard varieties of English. A beginning has been made in addressing the first two points by raising awareness of a ‘Scots bias’ which needs to be overcome, and by compiling the Scottish component of the International Corpus of English (ICE-Scotland).Footnote 4

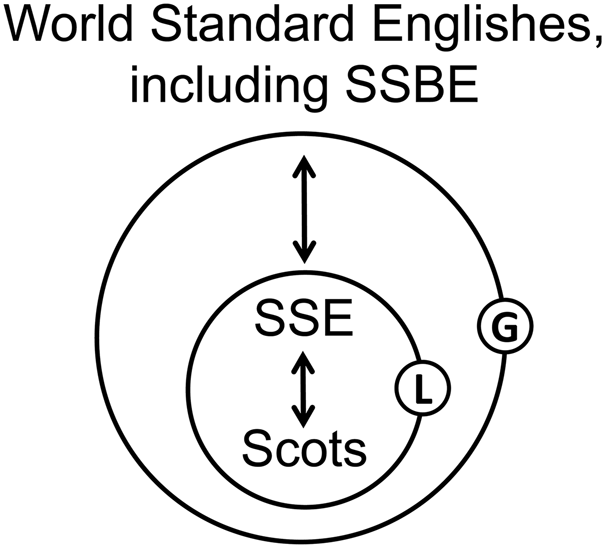

Our view of SSE is shown in figure 1, which expands the model by McArthur (Reference McArthur, Aitken and McArthur1979: 59; cf. Aitken Reference Aitken, Aitken and McArthur1979: 85) and is a slightly more compact version of the model developed in Schützler, Gut & Fuchs (Reference Schützler, Gut, Fuchs, Beal and Hancil2017: 282; cf. Schützler Reference Schützler2015: 25). We are interested in the standard pole (SSE) within the local continuum of variation and its position in an intervarietal context of variation – particularly concerning the influential close neighbour variety SBSE.

Figure 1. Local (L) and Global (G) continua of variation for SSE

Since the grammar of SSE is not codified, it is challenging to decide what to treat as standard usage. Our approach is guided by the data source: since ICE is dominated by language in standard genres, produced by educated speakers and writers, the forms that are produced qualify as SSE.

In what follows, we will look into relevant theoretical aspects of the core grammatical category of modality

3 Modality and modal verbs of strong obligation

Modality in the widest sense is about changes made to the meaning of clauses to express assessments of truth values or factuality (Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 221). Propositions are graded as more or less likely to be (or to become) factual, based on notions like possibility, permission, volition or obligation. Modality can be expressed in various ways (cf. Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 52; Leech Reference Leech, Marín-Arrese, Carretero, Hita and van der Auwera2013: 109), but modal and semi-modal verbs receive the greatest attention in linguistic research.

Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 219–20) distinguish two basic types of modality, (i) intrinsic, i.e. ‘intrinsic human control over events’ (permission, obligation, volition), and (ii) extrinsic, i.e. ‘human judgement of likelihoods’ (possibility, necessity, prediction). The extrinsic type is further subdivided, depending on whether or not it involves ‘human control’. In the following examples from Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 224–5), (1) is thus categorised as ‘(logical) necessity’, which Quirk et al. equate with ‘epistemic’; (2) is categorised as ‘root necessity’; and (3) is classified as ‘obligation or compulsion’ and stands apart from (1) and (2).

(1) There must be some mistake.

(2) To be healthy, a plant must receive a good supply of both sunshine and moisture.

(3) You must be back by ten o'clock.

Somewhat confusingly, there are two ‘root’ meanings of verbs like must in Quirk et al.'s scheme – exemplified as (2) and (3) – that belong to two different higher-level domains (necessity and obligation), although they seem closely related. For Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 52), example (1) would be a case of epistemic modality, while (2) and (3) would both be deontic, involving an element of obligation. The difference between the latter two is captured by the dichotomy subjective vs objective (Huddleston & Pullum Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002 et al.: 183). In subjective deontic modality, the deontic source – i.e. ‘[t]he person, authority, convention, or whatever from whom the obligation, etc., is understood to emanate’ (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 178) – coincides with the speaker/writer, or is clearly stated. In objective deontic modality, the speaker/writer states an obligation imposed by some other, more abstract agency. Thus, (4) and (5) are classified as subjective and objective, respectively (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 183).Footnote 5

(4) You must clean up this mess at once.

(5) We must make an appointment if we want to see the Dean.

A third type of modality identified by Huddleston & Pullum et al. is dynamic modality (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 52, 185). Here, the obligation derives from personal (and perhaps situational) properties, as in (6) and (7) from Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 185):

(6) Ed's a guy who must always be poking his nose into other people's business.

(7) Now that she has lost her job she must live extremely frugally.

Huddleston & Pullum et al. regard (6) as more prototypically dynamic: the necessity truly arises from the subject himself, while in (7) there is a more abstract ‘force of circumstance’. The central criterion for dynamic modality is the absence of a deontic source outside the closely delimited subject (e.g. ‘Ed’), or the situation itself. We would agree that in (6), the source of the obligation cannot be located outside Ed's character. In cases like (7), however, we would argue that circumstances, however abstract, may impose obligations and therefore constitute deontic sources.

Finally, Biber et al. (Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999: 485) apply a binary categorisation of modal meaning into (i) intrinsic (or deontic), in which case the situation is controlled via some agent (human or other), and (ii) extrinsic (or epistemic), which refers to the likelihood status of events or states (see Sweetser Reference Sweetser1990: 49). Crucially, Biber et al. (Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999) do not rely on a human source of obligation for the deontic category. In our analysis, we will adopt this more general framework: clear cases of epistemic and dynamic modality (examples (1) and (6)) are excluded, and the remaining deontic cases are classified as subjective or objective.

3.1 Differences between modal verbs of strong obligation

The verbs treated in this article belong in the category of strong obligation (see Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 176–7 for a differentiation between weak, medium and strong modality), since the proposed action appears (nearly) compulsory (see Sweetser Reference Sweetser1990: 54). We do not differentiate between stronger and weaker meanings between verbs, since these are ‘virtually impossible to categorize impartially’ (Tagliamonte & Smith Reference Tagliamonte and Smith2006: 345).

In Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 145), the four verbs are generally equivalent: have to and must are similar in meaning, have to and (have) got to are ‘semantically parallel’, and the relationship between all four is described as ‘close’ (226). More weight is given to grammatical differences. For instance, have to ‘can stand in for must in past constructions where must cannot occur’, and in contexts that require a nonfinite form. Such contexts also restrict the occurrence of (have) got to as opposed to have to (Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 145):

(8)

(a) I have to wait. / I (have) got to wait. / I must wait.

(b) I had to wait. / *I had got to wait. / *I musted wait.

(c) I will have to wait. / *I will (have) got to wait. / *I will must wait.

(d) I am having to wait. / *I am having got to wait. / *I am musting wait.

There is grammatical near-equivalence of need to and have to: substituting the former for the latter is unproblematic in sentences (8a–c), but marginally unacceptable in (8d).

The literature further reports that different verbs tend to be selected depending on whether the deontic source is subjective or objective. Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 183) find that objective cases are realised with have (got) to or need to, rather than must (see also Smith Reference Smith2003: 243–4), and Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 225–6) see must more strongly associated with subjective obligation than the ‘more impersonal’ have (got) to. Sweetser (Reference Sweetser1990: 53) says that, compared to must, have to ‘has more of a meaning of being obliged by extrinsically imposed authority’ and need to implies ‘that the obligation is imposed by something internal to the doer’ (cf. Talmy Reference Talmy1988). The view of need to as expressing an internally motivated obligation for the agent's own sake is also found in Smith (Reference Smith2003: 244–5); we will discuss possible theoretical consequences of this in section 3.4.

3.2 L1 varieties of English other than Scottish English

This section summarises research on modal verbs of strong obligation in L1 varieties of English – mostly American and British English (hereafter: AmE and BrE). The literature-based discussion of Scottish Englishes follows in the next section.

While the studies that are summarised show us the general frequencies of our verbs, they often do not disambiguate deontic and epistemic meanings, and furthermore take a traditional approach in counting and normalising frequencies based on super-categories (e.g. whole corpora, or corpus sections) without considering the hierarchical structure of such data sources. Our approach (see section 4.3) thus limits direct comparability with earlier studies. Finally, most studies report absolute (normalised) text frequencies, while we convert these to percentages relative to a category comprised of all occurrences of must, have to, need to and (have) got to.Footnote 6

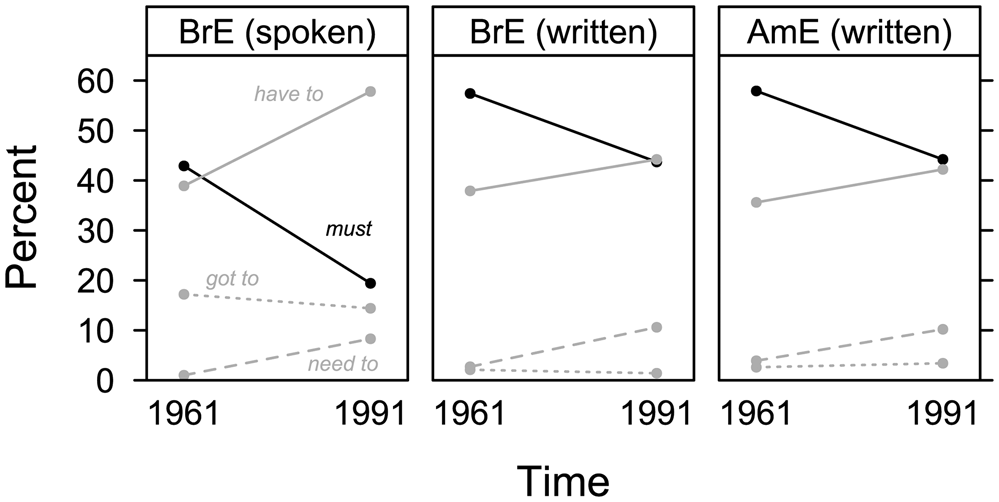

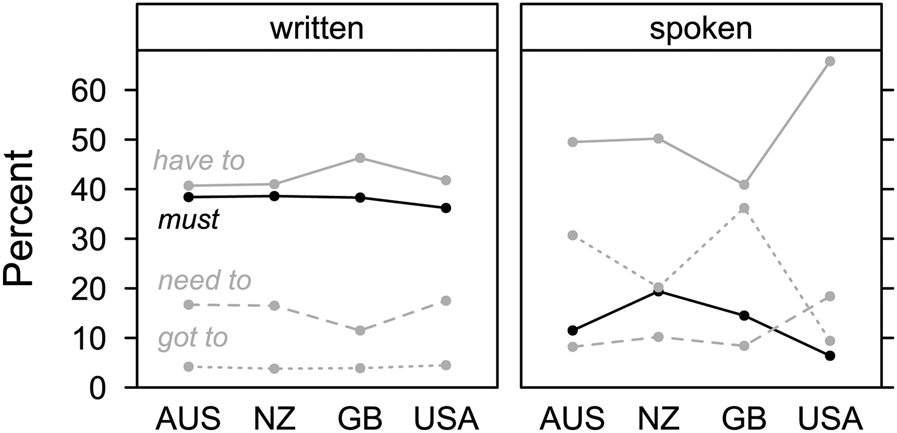

Figure 2 summarises Smith's (Reference Smith2003: 248–9) analysis of BrE and AmE.Footnote 7 It is based on written data from four corpora in the Brown family (e.g. Francis & Kučera Reference Francis and Kučera1979), complemented by two smaller spoken corpora of BrE.Footnote 8 No spoken AmE data were included.

Figure 2. Modals of strong obligation in late twentieth-century BrE and AmE (based on Smith Reference Smith2003: 248–9)

In the spoken BrE data, have to and (have) got to are generally more frequent than in writing; relative frequencies of must decrease and relative frequencies of have to and need to increase over time. Since Smith looks at individual and cumulated text frequencies, some of his conclusions are not borne out by our representation, for example concerning differences between written BrE and AmE (which are virtually non-existent in figure 2).

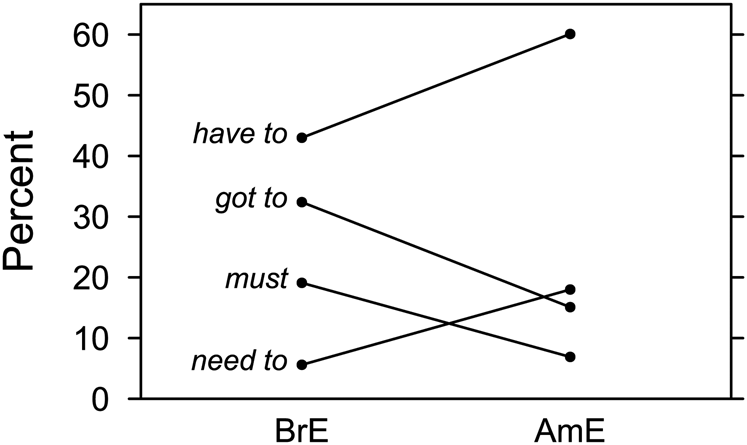

In figure 3, we reproduce spoken data from the demographic (spoken) subcorpus of the British National Corpus and the Longman Corpus of Spoken American English, both representative of 1990s usage, as published in Leech (Reference Leech, Marín-Arrese, Carretero, Hita and van der Auwera2013: 112). This analysis, too, is entirely form-driven.

Figure 3. Modal verbs of strong obligation in spoken BrE and AmE (based on Leech Reference Leech, Marín-Arrese, Carretero, Hita and van der Auwera2013: 112)

Results in BrE agree with Smith's (Reference Smith2003) data in the first panel of figure 2, except that in the BNC (have) got to is more frequent. There is also a marked difference between BrE and AmE, the latter showing a more pronounced preference for have to and need to, at the expense of must and (have) got to.

In figure 4, we re-visualise central results from Collins (Reference Collins2009).Footnote 9 Our focus is on L1 varieties only. In writing, the pattern is relatively stable across the four varieties under investigation (Australian, New Zealand, British and US-American English), with high frequencies of have to and must, lower frequencies of need to, and low frequencies of (have) got to – see results from Smith (Reference Smith2003) in figure 2. In speech, with few exeptions, have to and (have) got to are used more, while must is much less frequent and need to is somewhat less frequent.

Figure 4. Modal verbs of strong obligation in L1 varieties of English (based on Collins Reference Collins2009: 285–6)

Finally, Millar (Reference Millar2009) inspects diachronic developments in the frequencies of modal verbs in the TIME Magazine Corpus (Davies Reference Davies2007–). He finds a clear twentieth-century trend with must decreasing and have to and need to increasing in frequency, while (have) got to does not change much.

3.3 Scottish English

Differences between modal verb usage in SSE and SBSE are commented on by Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 220), who say that ‘Scots, Irish, and Northern English varieties resemble AmE in some respects more than they resemble the “standard” southern usage …’. In the following paragraphs, we avoid the issue of double-modal constructions – which may be what Quirk et al. allude to – although these have received a good deal of attention (e.g. Miller & Brown Reference Miller and Brown1982: 12–13; Brown Reference Brown, Trudgill and Chambers1991; Fennel & Butters Reference Fennel, Butters and Schneider1996: 273). In our data, such constructions did not occur, and it seems likely that double modals do not play a role in standard usage in Scotland.Footnote 10 The studies cited in this section do not explicitly target standard language, and it is therefore uncertain to what extent the described tendencies can be generalised to SSE.

Miller & Brown (Reference Miller and Brown1982: 8) list five modal verbs for the expression of necessity in Scottish English: must, have to, will have to, (have) got to and need to. There is a strong restriction of must to its epistemic sense, as in (9) (see also Aitken Reference Aitken, Aitken and McArthur1979: 105; Kirk Reference Kirk, Macafee and Macleod1987; Miller Reference Miller, Milroy and Milroy1989: 16–17; Reference Miller, Kortmann and Upton2008: 305). The epistemic sense is generally regarded as more recent than the deontic sense, illustrated in (10) (cf. Sweetser Reference Sweetser1990; Tagliamonte & Smith Reference Tagliamonte and Smith2006):

(9) I keep thinking about the other tenants in the building and how they must be feeling. (ICE-SCO-rep-056)

(10) Scotland's mountains and wild lands are one of our greatest treasures and must be protected. (ICE-SCO-rep-062)

According to Miller & Brown (Reference Miller and Brown1982), it is need to and have to that are mainly used for the expression of necessity. must is stronger (or more emphatic), but Miller & Brown suspect that there is no difference between have to and must concerning the deontic source. In the same context, need to is described as ‘no less strong than must or have to’. Finally, Miller & Brown (Reference Miller and Brown1982: 10) comment that the form will have to may be used where other varieties use must. Two examples from ICE-Scotland show that seemingly futurate uses of need to and have to can be used with a meaning equivalent to a present-tense form:

(11) This candidate drug will need to undergo further preclinical testing before it can be taken forward into clinical trials […]. (ICE-SCO-PNat-13)

(12) [This] means that the government has adopted Labour's shale gas policy and will have to bring in new environmental regulations before fracking can be allowed. (ICE-SCO-rep-73)

Forms like these are perhaps only formally marked for future, without any future meaning proper.

Two Scottish dialects are included in Tagliamonte & Smith's (Reference Tagliamonte and Smith2006) study: Buckie (in the present-day council area of Moray) and Cumnock (East Ayrshire). For methodological reasons, their results cannot be straightforwardly related to our own findings. What can be said, however, is that the two regional Scottish varieties seem to be rather different (see Tagliamonte & Smith Reference Tagliamonte and Smith2006: 366, table 3). Relative to the average behaviour of dialects, Buckie speakers simply do not use must, strongly prefer have to and disprefer (have) got to; Cumnock speakers, however, are very close indeed to the cross-dialectal average. The verb need to is not included, which additionally complicates a direct comparison to our data. Using a selection of crossed language-internal factors, Tagliamonte & Smith (Reference Tagliamonte and Smith2006: 363) further find that a subjective deontic source correlates with must, and an objective one with have to, at least with first- and third-person subjects.

The main task of the analyses presented in section 5 will be to establish whether the (more vernacular) patterns reported above have a parallel in SSE as documented in ICE-Scotland.

3.4 Mechanisms of change: grammaticalisation, democratisation and reallocation

Like Tagliamonte & Smith (Reference Tagliamonte and Smith2006: 344), we interpret the coexistence of semantically equivalent modals or semi-modals as a case of layering in the sense of Hopper (Reference Hopper, Traugott and Heine1991: 22–4). In grammaticalisation (Hopper & Traugott Reference Hopper and Traugott2003), existing forms take on new (grammatical or semantic) functions and become layered with older, functionally similar forms. For must, have to and have got to, the process is summarised by Tagliamonte & Smith (Reference Tagliamonte and Smith2006: 346–8): Germanic predecessors of must were part of Old English, while have to is first attested in Middle English, became more established in Early Modern English, and developed further – e.g. into (have) got to and its even more compacted and modalised form gotta – from the nineteenth century onwards (see also Krug Reference Krug2000). need to followed a grammaticalisation path roughly comparable to have to (OED online, s.v. ‘need, v.2’).

However, grammaticalisation as an intra-systemic mechanism of change does not explain why a change happens. There seem to be mainly two factors that can motivate changes in our verbs. The first one assumes a process of democratisation (e.g. Farrelly & Seoane Reference Farrelly, Seoane, Nevalainen and Traugott2012), which Leech et al. (Reference Leech, Hundt, Mair and Smith2009: 259) define as a discourse-pragmatic (i.e. linguistic) correlate of ‘changing norms in personal relations’ – a kind of language change directly linked to (and caused by) changes in society. The adoption of different modal verbs for the coding of strong obligation would seem to fall into a category that Schützler (Reference Schützler2020) calls ‘explicit democratisation’, i.e. the avoidance of overt linguistic markers of inequality or power asymmetry (see Fairclough Reference Fairclough1992). This is consistent with Smith's (Reference Smith2003: 263) description of deontic must as ‘prototypically subjective and insistent, sometimes authoritarian-sounding’ and therefore ‘likely to be increasingly avoided in a culture where overt markers of power or hierarchy are much less in favour’. The avoidance of must can then be compensated for by increased frequencies of have to and need to. Associated with objective deontic sources, the former avoids the impression of a direct imposition of speaker authority. Concerning need to, Smith (Reference Smith2003: 263–4; cf. Leech Reference Leech2003: 237) writes that it ‘is (ostensibly at least) not an overt marker of power’ and can thus serve as ‘an indirect means of laying down obligations’. As Smith (Reference Smith2003: 244–5) points out, need to may express a (potentially strong) directive that poses, so to speak, as a recommendation in the addressee's own interest.

Secondly, and notwithstanding possible differences in their typical deontic source configuration (see section 3.1), the basic functional equivalence of verbs postulated in Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985; cf. Talmy Reference Talmy1988: 86) makes it quite likely that they have been reallocated to socio-stylistic (including dialect-marking) functions (see Trudgill Reference Trudgill1986: 118–21; Britain & Trudgill Reference Britain, Trudgill and Mattheier2000: 73–4). Stylistic differences of the verbs are discussed by Talmy (Reference Talmy1988: 77), who comments on the colloquial character of have to relative to must, Leech et al. (Reference Leech, Hundt, Mair and Smith2009: 95), who remark upon (have) got to as a colloquialism, as well as Biber et al. (Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999: 489), who compare a number of verbs concerning their distribution across broad genres. We will make such comparison at a very general level by comparing speech and writing, since our central concern is the function of verbs as dialect markers that signal a difference between SBSE and SSE.

4 Research questions, data and methodology

4.1 Research questions and expectations

Our main research question is whether or not SSE does indeed follow different strategies when encoding strong obligation with the verbs must, have to, need to and (have) got to. Miller (Reference Miller, Milroy and Milroy1989: 17) foreshadows our expectation:

My impression … is that need occurs frequently. I at one time imagined that it was more frequent than have to, but this is not borne out by the recorded data. It may well be, however, that need is used more frequently by speakers of Scottish English than by speakers of other varieties.

We expect that must is used less in SSE, while have to and particularly need to are used more, compared to SBSE. We further expect those differences to surface more strongly in spoken language, since writing will be characterised to a greater extent by the kind of ‘text-linked World Standard’ postulated by McArthur (Reference McArthur1987: 10).

Due to the socio-stylistic values of verbs, we expect higher relative frequencies of have to, need to and (have) got to in speech, while must retains a relatively central position in writing. Further, if we accept the association of must with overtly expressed authority, this verb should be less frequent in connection with subjects in the second-person. Finally, we expect an association of have to with objective obligation. Apart from general differences between varieties, we will also inspect whether or not intra-linguistic or contextual factors (grammatical subject, deontic source, mode of production) have similar effects in SSE and SBSE, or whether they, too, are variety-specific.

4.2 Data retrieval and coding

We used two components of the International Corpus of English (ICE): ICE-GB (Nelson, Wallis & Aarts Reference Nelson, Wallis and Aarts2002; Kirk & Nelson Reference Kirk and Nelson2018) and ICE-Scotland (‘ICE-SCO’; Schützler, Gut & Fuchs Reference Schützler, Gut, Fuchs, Beal and Hancil2017). We included material from 21 genres. With the concordancing software AntConc (Anthony Reference Anthony2018), we retrieved occurrences of <must>, <have to>, <has to>, <need to>, <needs to> and <got to>. Nonfinite forms (e.g. will have to, might need to), interrogatives, past-tense forms, as well as negations were excluded, as were all epistemic instances (predominantly of must) and non-obligation meanings of got to (e.g. They got to be friends). The categories ‘legal cross-examinations’ and ‘business letters’ – at the time of analysis represented by n = 4 and n = 6 texts, respectively, in ICE-SCO – did not yield valid hits in SSE and were excluded to maintain the genre balance between corpora. Eventually, the analysis was thus based on n = 19 genres (9 spoken, 10 written). Genres and total numbers of texts and words are documented in appendix A.

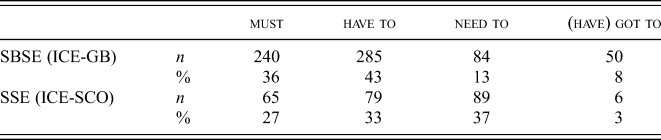

We obtained n = 898 tokens, distributed across n = 332 individual texts. This number of texts is considerably lower than the number that were searched (n = 607) – not necessarily because none of our verbs occurred in the remaining n = 275 texts, but because the retrieved cases did not meet the necessary grammatical and semantic criteria. Raw counts and percentages (per variety) are shown in table 1.

Table 1. Raw counts and percentages of verbs

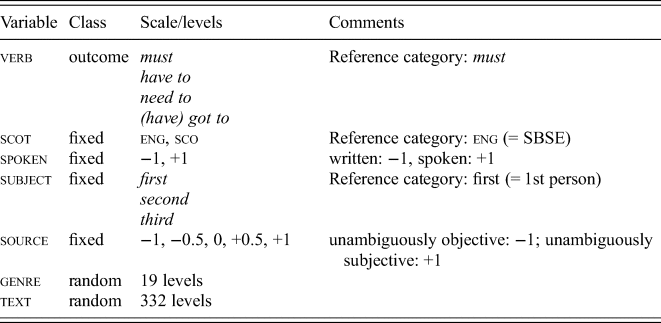

Cases were coded for the variables shown in table 2. Grammatical coding and the exclusion of false positives and epistemic cases were done by the second author, supported by Zeyu Li at the University of Münster. Rare instances of disagreement were discussed and resolved in cooperation with author one. Concerning deontic source, both authors independently awarded scores of −1 (objective), +1 (subjective) and 0 (intermediate/unclassified). Cases of disagreement were only resolved if there had been an obvious error. In other cases, the two ratings were averaged – thus, the predictor source can take five numerical values.

Table 2. Definition of variables

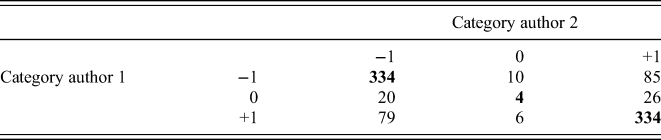

Our way of handling semantic classification reduces loss of information as well as the pressure involved in making a forced decision. The two sets of ratings are cross-tabulated in table 3.

Table 3. Deontic source: agreement between raters

Relative observed agreement was at 74.8 per cent: both raters awarded the same score in 672 out of 898 cases. Considering that we are dealing with semantic disambiguation, this is a good rate, even if complete disagreement (with exactly opposite ratings) was also substantial (164/898 = 18.3 per cent). Apart from true inter-rater errors, this figure may partly be explained from the fact that (i) it was not feasible to inspect the full context of examples, and that (ii) many examples are truly ambiguous. By averaging the two scores for deontic source, we neutralise conflicting cases in a consistent, non-lossy way.

4.3 Statistical modelling and visualisation

We worked in the R-environment (R Core Team 2019), using RStudio (RStudio Team 2009–19). Visualisations were done with functions in the R-package ‘lattice’ (Sarkar Reference Sarkar2018). With the variables in table 2, we fitted a Bayesian multinomial mixed-effects model to the data, using the R-package ‘brms’ (Bürkner Reference Bürkner2020), which is based on Stan (Stan Development Team 2019). A multinomial model has more than two possible categorical outcomes, whose probabilities under the influence of different factors are estimated. In this case there are four possible outcomes corresponding to the four modal verbs under investigation, encoded in the variable verb. Predictor variables were subject, source and spoken, each of which was specified as interacting with variety. In other words: the model allowed for the possibility that subject, source and spoken take different effects on the selection of verbs in SBSE and SSE. For the exact model specification, a discussion of the priors that were used, as well as for further information see appendix B.

The plots show median values of the estimated percentages of the four verbs under different conditions, as well as their dispersion, expressed as 50% and 90% percentile-based posterior uncertainty intervals. Such intervals will sometimes be reported in the text. For instance, in figure 5, the percentage point difference between spoken SSE and spoken SBSE for need to can be given as ‘22.1% [10.3, 36.3]’, which means ‘a median difference of 22.1% with a 90% uncertainty interval extending from 10.3% to 36.3%’.

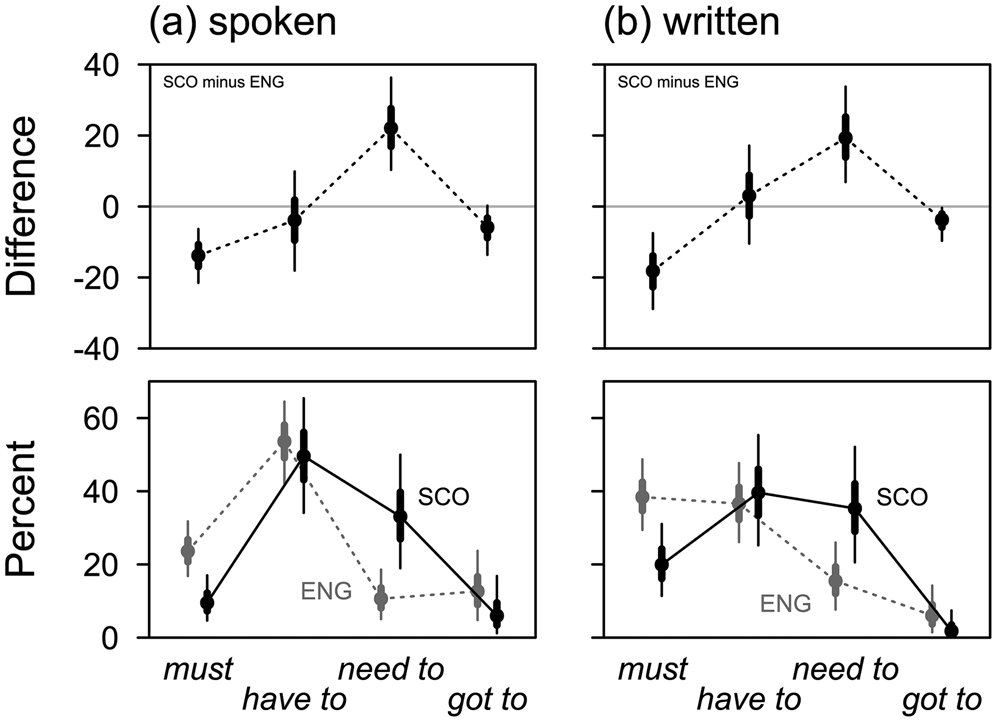

Figure 5. SSE vs SBSE: percentages and differences by verb and mode of production ![]()

Factors of no immediate interest in a given scenario are held constant. The exact routine is made transparent on https://osf.io/aq2r5/ (see section 4.4 below). Intuitively, it may seem to be problematic to assume normal (or average) values for mode of production or grammatical subject, since, in reality, these parameters take categorical values at any one time.Footnote 11 However, this approach allows us to target specific effects and thus makes results more accessible.

Concerning the fixed part, no model comparison or model selection process was conducted, since it was considered essential to retain all theoretically important predictors in the model, irrespective of their estimated effects (cf. Heinze, Wallisch & Dunkler Reference Heinze, Wallisch and Dunkler2018); we thus adopted the notion of the ‘deductive model’ as proposed by Tizón-Couto & Lorenz (Reference Tizón-Couto and Lorenz2015). No p-values are calculated for individual coefficients, since we prefer an estimation approach to (less informative) null hypothesis testing. The reader can assess the robustness of an effect by looking at the uncertainty interval of the estimated difference (the effect size). If the interval cuts across the critical value of zero, results need to be treated with caution. The table in appendix C provides the complete fixed-effects part of the model output, as well as basic information on the random effects. Concerning the random part, the inclusion of text as a cluster variable seemed absolutely necessary, and in our inclusion of genre we were guided by the structure of the ICE corpus. The random-effects structure at the level of text is maximal, i.e. it mirrors the fixed effects and thus makes them more precise.

4.4 Open data

The dataset used in the present study is published as Schützler & Herzky (Reference Schützler and Herzky2021) at the Tromsø Repository of Language and Linguistics (TROLLing; see references). R-scripts used in the analysis can be retrieved from https://osf.io/aq2r5/. Readers are thus enabled to understand our approach more fully, incorporate our data into their own analyses, adapt our models (e.g. by using different priors, including more interactions, or specifying different random effects) or to implement altogether different kinds of models (e.g. of a non-Bayesian type) or statistical tests. The osf-repository also contains the scripts for the generation of figures 5–10, along with the figures themselves (in svg-format). For the entire repository, we selected a CC BY 4.0 licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) and marked the respective figures in the captions, thus: ![]() .

.

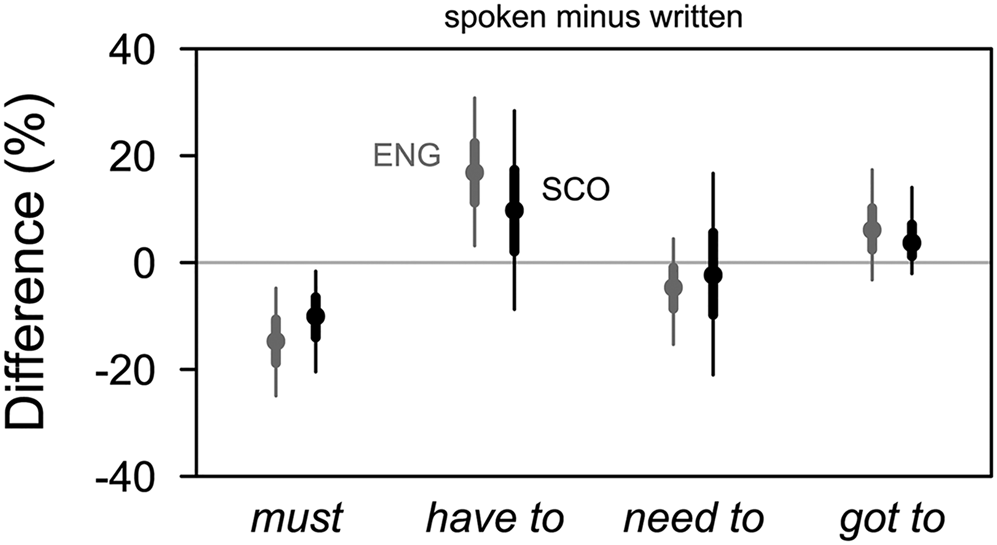

Figure 6. Speech vs writing: differences by verb and variety ![]()

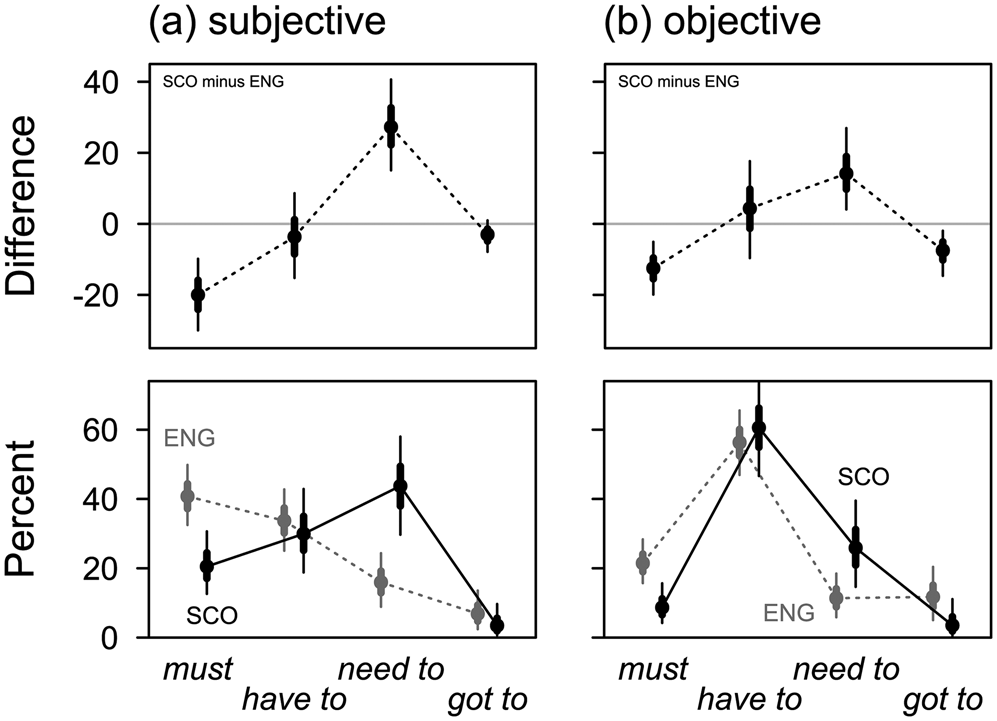

Figure 7. SSE vs SBSE: percentages and differences by verb and source of obligation ![]()

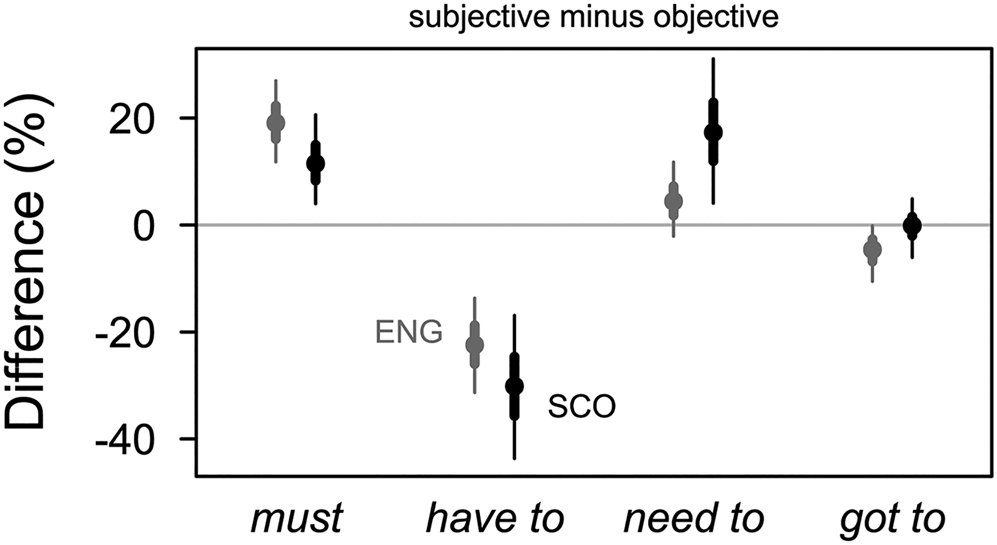

Figure 8. Subjective vs objective source of obligation: differences by verb and variety ![]()

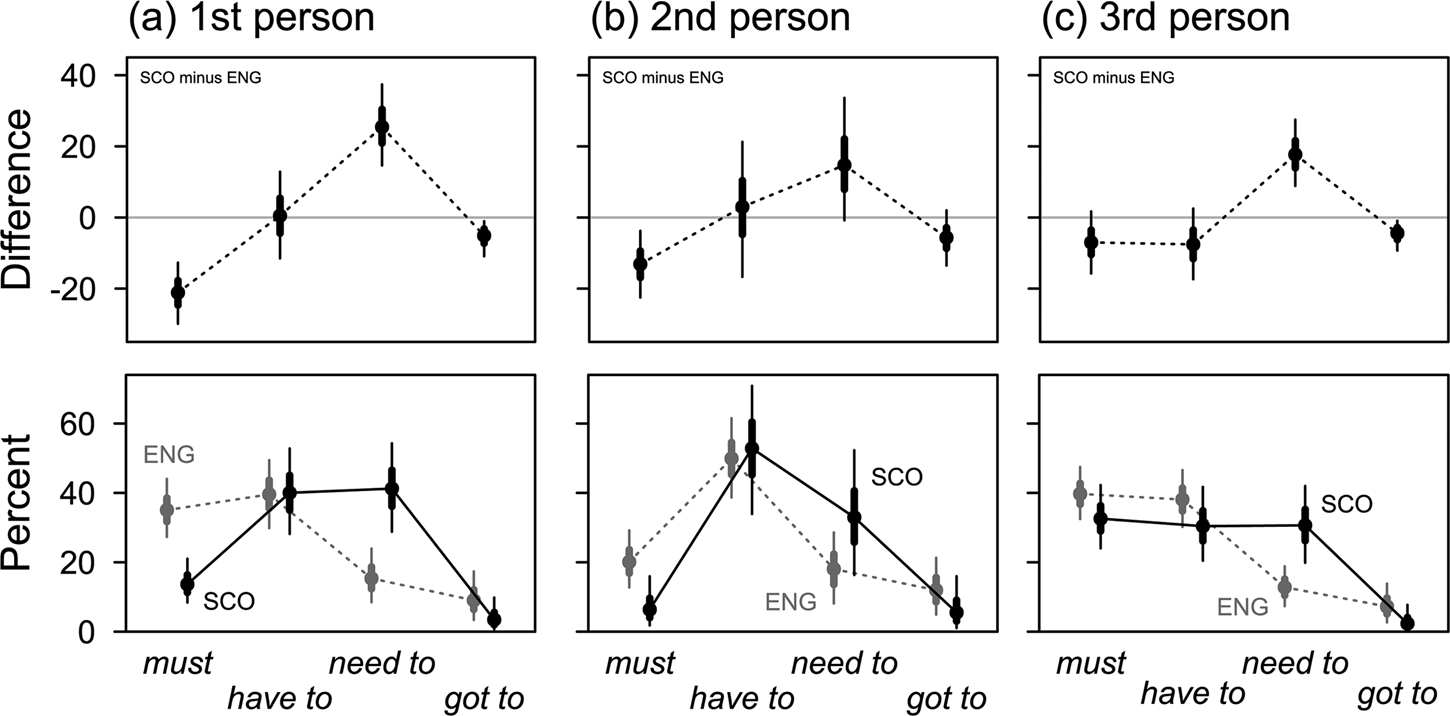

Figure 9. SSE vs SBSE: percentages and differences by verb and grammatical subject ![]()

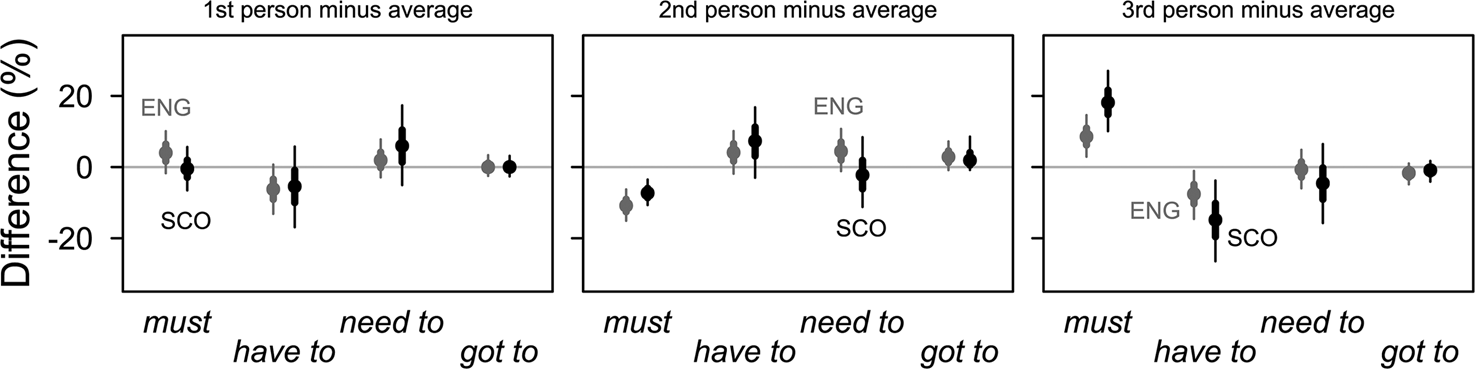

Figure 10. Grammatical subjects: differences by verb and variety ![]()

5 Results

Each of the following subsections focuses on one of three contrasts: speech vs writing, objective vs subjective sources of obligation, and the differences between grammatical subjects. For different conditions, estimated percentages of the four verbal categories are plotted for SSE and SBSE, controlling for other factors. Additionally, the percentage point differences between the two varieties are estimated and plotted. The reader can thus see at a glance (i) the expected proportions of verbal categories in each variety and (ii) the magnitude and robustness of the difference between SSE and SBSE. In addition, the effects of a difference (like speech vs writing) on specific verbs are gauged.

5.1 Speech and writing

We turn first to the difference between modes of production. The bottom panels in parts (a) and (b) of figure 5 show estimated percentages of the four verbs in speech and writing; the panels on the top compare the two variety-based patterns by subtracting percentages in SBSE from percentages in SSE. For the sake of clarity, we use the labels ‘SCO’ and ‘ENG’, rather than ‘SSE’ and ‘SBSE’.

In speech, the preferred verb in both varieties is have to, at 53.6% in SBSE and 49.6% in SSE. The difference is small enough to be passed over quickly. need to is used at rates of 33.1% in SSE and 10.6% in SBSE, respectively. This preference for need to in SSE is one of the two main differences between varieties. The second major difference concerns the relative frequency of must, which is 23.6% in SBSE and 9.5% in SSE. Again, the difference is quite robust. Finally, (have) got to is used more frequently in SBSE (12.7%) than in SSE (6.0%).

In writing, the general pattern is fundamentally different. In both varieties, the percentage of must is higher than in speech, with 38.4% in SBSE and 19.9% in SSE; percentages of have to are lower but still fairly similar in both varieties; frequencies of need to are somewhat higher; and frequencies of (have) got to are lower than in speech. Thus, all verbs, perhaps with the exception of need to, respond to the difference between modes. Crucially, however, the systematic differences between SSE and SBSE hold across speech and writing, as shown in the top panels of figure 5: must and (have) got to are more frequent in SBSE, need to is more frequent in SSE, and have to is roughly equally frequent. The following two examples show an instance of written must and spoken have to from ICE-SCO.

(13) Current legislation dictates that sprinklers must be fitted in all care homes and sheltered housing […] (ICE-SCO-rep-056)

(14) […] this is a scandal […] we have to expose what went on here in Scotland […] (ICE-SCO-btal-036)

Figure 6 reorganises the information contained in figure 5 to focus on how the frequencies of individual verbs are affected by modes of production. Individual verbs’ responses to the two conditions are more clearly visible here. Two verbs – have to and and (have) got to – associate with speech, must associates with writing, and need to is relatively indifferent in SSE, perhaps tending towards the written mode in SBSE. Crucially, the effects point in the same direction in both varieties, although they differ in magnitude. Whatever the general differences in patterns between SBSE and SSE, the stylistic value of the four verbs seems to be similar, at least at this general level.

In section 3.4, we discussed the more colloquial character of have to and (have) got to. If we accept speech and writing as very broad stylistic categories, the behaviour of the two verbs in our data is consonant with those accounts.

5.2 Sources of obligation

In this section, we inspect subjective and objective sources of obligation, holding other factors constant. As discussed in section 3.1, the source of objective authority lies outside the speaker or writer, which is often the case in rules and regulations, while in subjective cases the authority is imposed by the speaking or writing subject (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 183; Tagliamonte & Smith Reference Tagliamonte and Smith2006: 361–2).

Figure 7 shows estimated percentages of the four verbs in the bottom panels, and compares the two variety-based patterns in the top panels. Irrespective of the results we discuss below, the general difference between the two varieties holds true from this perspective, too: Compared to SBSE, need to is substantially more frequent in SSE, must is substantially less frequent, and (have) got to is somewhat less frequent.

Further, the difference between subjective and objective obligation correlates with the choice of verb in similar ways as the difference between writing and speech. Due to this similarity of the effects, there is considerable similarity between figures 5a and 7b, as well as between figures 5b and 7a, and we can therefore let figure 7 speak for itself.

In analogy to figure 6, figure 8 focuses on the behaviour of verbs between conditions. Subjective obligation disfavours have to in both varieties (see Tagliamonte & Smith Reference Tagliamonte and Smith2006: 362): Compared to objective obligation, the respective relative frequencies of have to are lower by 22.4% [13.7, 31.3] in SBSE and 30.1% [16.9, 43.7] in SSE.Footnote 12 On the other hand, must is more common with this type of deontic source (see Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002). In our data, need to is associated with subjective sources of obligation, particularly in SSE, where its relative frequency is higher by 17.3% [4.1, 31.1] in this condition, compared to objective deontic sources.

We conclude that the general difference between SBSE and SSE concerning relative frequencies of must, need to and (have) got to is robust, even if we isolate the two deontic sources. Secondly, the impact of deontic source on the choice of modal verb is similar in both varieties.

5.3 Grammatical subjects

The analysis of the relationship between grammatical subjects and verb selection is guided by the idea that notionally authoritarian items like must should occur less frequently when there is a second-person addressee. Figure 9 shows frequency patterns in a form familiar from above, with the direct comparison of SSE and SBSE in the top panels. We concentrate on those characteristics that stand out in each condition.

With second-person subjects, must is considerably less frequent than with first- or third-person subjects, at 6.4% in SSE and 20.1% in SBSE. At the same time, have to is the majority variant in both varieties (SSE: 52.8%; SBSE: 49.9%). Third-person subjects, however, associate strongly with the verb must, which is the majority variant in both varieties in this condition (SSE: 32.6%; SBSE: 39.7%). This is remarkable, given that SSE generally uses this verb less when compared to SBSE (see above). As a result, the pattern recurrently observed in the top panels of earlier figures – less must and more need to in SSE, relatively indifferent behaviour of have to and (have) got to – is qualified with third-person subjects: In this context, the otherwise marked difference between varieties concerning frequencies of must virtually disappears. Only a small and not particularly robust difference remains.

For the direct inspection of the behaviour of individual verbs in figure 10, we compare the estimated frequencies of verbs in combination with any of the three subject conditions to an idealised average value (see section 4.3). This was preferred to a less informative pairwise comparison of subject conditions.

Figure 10 highlights the main differences discussed above. Variation conditioned by first-person subjects is rather limited; with second-person subjects, percentages of must are much lower in both varieties, by 7.3% [3.5, 10.7] in SSE and by 10.8% [6.3, 15.1] in SBSE; in the third person, must is above average by 18.1% [10.1, 27.0] in SSE and by 8.6% [2.9, 14.6] in SBSE, while have to is below average by 14.8% [3.8, 26.5] in SSE and by 7.6% [1.1, 14.6] in SBSE. The verbs need to and (have) got to do not respond much to grammatical-subject conditions. For illustration, the following two examples show third-person subjects in combination with must and have to, respectively.

(15) SNP must face economic realities (ICE-SCO-ed-021)

(16) [T]he Labour Party has to be at the forefront of the Labour Movement (ICE-SCO-nbtal-011)

A straightforward reading of the examples as conditioned by grammatical subjects is hampered not only by the headline style of (15), but also by the fact that deontic source seems to play a major role as well, probably with an objective source in (15) and a subjective one in (16).

6 Conclusion and outlook

There are both similarities and systematic differences between SSE and SBSE concerning the use of the four modal verbs of strong obligation, must, have to, need to and (have) got to. Against the background of rather different baseline frequencies of the four verbs, the contextual, semantic and syntactic factors that govern the concrete choice of verb are remarkably similar:

i. In both varieties, must and – to a much lesser extent – need to are associated with written language, while have to and – to a lesser extent – (have) got to are associated with spoken language. If we accept that the basic difference between speech and writing correlates with basic stylistic categories, our results are in agreement with descriptions of must as more formal than have to and (have) got to. The correlation of need to with writing is a new insight.

ii. In both varieties, subjective deontic sources of obligation correlate positively with higher rates of must and need to, while objective deontic sources correlate with have to. For must, this pattern has been reported before, but to the best of our knowledge it has not been connected with need to. The association of need to with subjective deontic sources may be a yet unknown characteristic of its grammaticalisation path in English more generally. However, we regard it as an interesting indication rather than a conclusive result, and its further exploration must be left to independent follow-up research.

iii. In both SSE and SBSE, must tends to be used less with grammatical subjects in the second person, while have to is used more in this context. In contrast, with third-person subjects, there are increased frequencies of must and lower frequencies of have to. These patterns may be due to face-saving strategies: when directly telling someone what s/he should do, have to with its implied objective-obligation meaning is substituted for overtly authoritarian must.

Independently from the above constraints, both varieties appear to be characterised by different basic preferences concerning modal verbs of strong obligation. In SSE, need to is used more frequently than in SBSE; in contrast, SBSE shows higher relative frequencies of (have) got to and particularly of must. We would argue that SSE has developed need to as a strongly grammaticalised alternative to must, which is supported by the fact that both verbs are functionally similar, i.e. associated with writing and subjective deontic sources. Like have to, the verb need to is ‘softer’ in a social sense, since it is traditionally linked to self-motivated obligation (cf. Talmy Reference Talmy1988; Sweetser Reference Sweetser1990; Smith Reference Smith2003). Although in our data need to – like must – is linked to subjective (i.e. directly imposed) obligation and possibly to formal contexts, it may still serve as a more diplomatic (or democratic) functional equivalent of must.

With regard to our study, it is of course problematic that there is a considerable time gap between ICE-GB and ICE-SCO. As some of the research summarised in section 3 shows, there have been substantial diachronic developments in the system of modal verbs between the 1960s and the 1990s, and such trends may well have continued up to the present day. There is no easy solution to this problem: we have no corpora that represent SSE in the 1990s, and those corpora that could be used to assess present-day SBSE are either written-only – e.g. the BE06 corpus (Baker Reference Baker2009) – or follow sampling frames different from ICE (e.g. BNC2014; Love et al. Reference Love, Dembry, Hardie, Brezina and McEnery2017). The way forward is likely to be some kind of corpus-triangulation approach, in which a more robust picture is assembled from carefully handled heterogeneous sources (ICE-SCO, BNC2014, Brown-family corpora). Given this problem, we make no claims for our research to be definitive; rather, we offer it as a reference point for future efforts, including our own.

We see three possible extensions of our present research. First, there is a distinction not only between grammatical subjects in different persons, but also between what has been called ‘definite’ vs ‘indefinite’ (or ‘generic’) subjects (see Tagliamonte & Smith Reference Tagliamonte and Smith2006). The following examples illustrate the difference, showing definite subjective (17), definite objective (18) and indefinite objective cases (19), respectively:

(17) You must come and visit us as soon as you can. (ICE-GB-W1B-004)

(18) Yet the design has to be visible and distinctive so potential readers can quickly select their favourite newspaper […]. (ICE-SCO-ed-32)

(19) To work in high performance sport you have to be determined […] (ICE-SCO-Rep-09)

Including the definite-generic distinction in the analysis would certainly require more data. Diachronic and synchronic corpora large enough for this kind of undertaking exist for BrE and AmE, but it is doubtful whether ICE-SCO, even in its completed form, will be large enough.

Secondly, quasi-futurate forms – illustrated in examples (11) and (12) in section 3.3 – may play a special role in SSE. Future meaning is an implicit concomitant of obligation, as pointed out by Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 217) with regard to must. In many constructions that combine finite will with the infinitive of have to or need to, temporal deixis may therefore be much less important than a general softening effect achieved by making futurity explicit and thus reducing the immediacy of the imposed obligation. However, incorporating this into our quantitative approach would involve similar quantity-related issues as the inclusion of the definite-generic distinction of subjects. In our data, will have to and will need to were rare, but they may well be one of the more subtle grammatical Scotticisms in SSE.

Despite these caveats and reservations, we have taken a step towards a better description of SSE concerning a central element of grammar. While, as expected, SSE and SBSE draw on the same basic system of modal verbs of obligation, the categories involved seem to have grammaticalised to different extents in the two varieties. SBSE is more traditional in using must at higher rates, but has also developed (have) got to as an alternative (see Krug Reference Krug2000). In SSE, need to has grammaticalised much more strongly, while (have) got to is less frequent. The notion of greater or lesser conservatism cannot be applied across the board. Rather, modal verbs grammaticalised along different trajectories in both varieties.

Concerning our object of investigation, one could perhaps speak of a British standard in the sense that both SSE and SBSE respond very similarly to factors like mode of production, deontic source and grammatical subject configuration. This shared set of rules, however, contrasts with different preferences of a more general kind. Consequently, the two major standard dialects in mainland Britain are characterised by unity and diversity at different levels. We will take this forward as a working hypothesis for our ongoing research on this topic.

Appendix

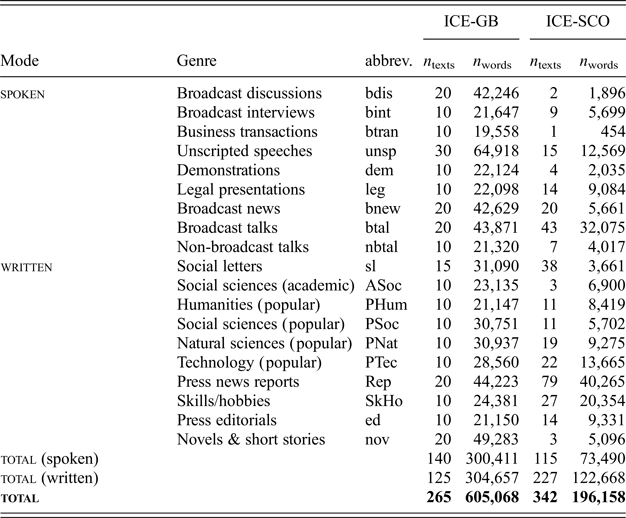

A. Corpus sizes: genres, numbers of texts and words

Although ICE-GB was purged of extra-corpus material, the word count is rather too high for some text categories. Divergent figures for ICE-GB and ICE-SCO are due to the latter being still under construction. It also follows a somewhat different sampling approach, in that texts shorter than 2,000 words were accepted.

B. Model specification

The model was set up as a multinomial regression model with four outcome categories, the reference category being the verb must. Priors were specified as documented in the full model syntax below. The model was run with n = 4,750 iterations in four chains, each with a warmup of n = 1,000 iterations. The resulting number of posterior samples was n = 15,000. Model diagnostics indicated the convergence of chains (R-hat = 1.00 for all parameters; see appendix C).

brm(verb ~ (subject + source + spoken) * scot

+ (subject + source | text)

+ (1 | genre),

family = "categorical", data = modals,

warmup = 1000, iter = 4750, cores = 3, chains = 4,

prior=c(

set_prior("normal(0, 3)", class = "Intercept"),

set_prior("normal(0, 2)", class = "b"),

set_prior("normal(0, 2)", class = "sd", dpar = "muhaveto"),

set_prior("normal(0, 2)", class = "sd", dpar = "muhavegotto"),

set_prior("normal(0, 2)", class = "sd", dpar = "muneedto")

),

control = list(adapt_delta = .96)

)

We tested the reported model against two models, one with random intercepts only for text and genre, the other with the complete random-effects structure for text but without random effects based on genre. Our model was evaluated as better than the less complex ones, based on the Leave-one-out Information Criterion (LOOIC).

To check for prior sensitivity, a model with relaxed priors was run, defining the prior of the intercept as ‘normal(0, 6)’ and the remaining four priors as ‘normal(0, 3)’. This model was characterised by larger estimates for the standard deviations of several random coefficients. However, the visual inspection of predicted percentages did not reveal any differences that ran against our original conclusions, although uncertainties tended to increase. The model summary shown when applying the function print() to the model object in R is documented on the osf-repository (see section 4.4).

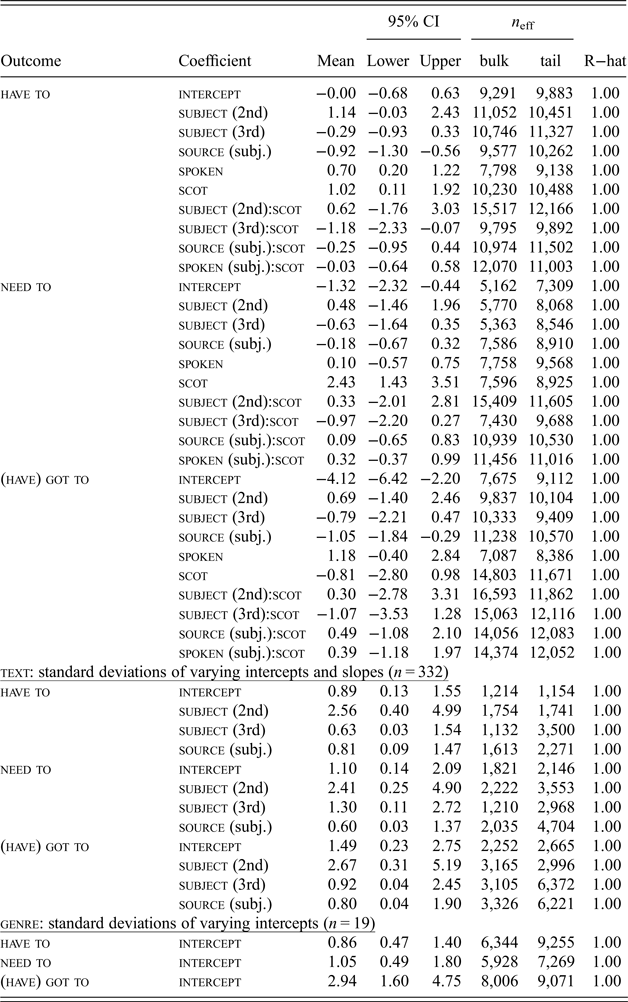

C. Regression table