Educational Psychology Assessment

It has often been argued that a question frequently neglected by educational psychologists is: Why am I carrying out this assessment? The goals for carrying out an assessment should be clarified first before embarking on the process (Haywood & Lidz, Reference Haywood and Lidz2007). It has been argued that there is often a huge misunderstanding made by psychologists whereby the most up-to-date technique is taken from the shelf without pausing to consider why one is carrying out the assessment (Cizek, Reference Cizek and Phye1997). Prior to embarking on the assessment process, there may be far too little attention paid to essential questions regarding the purposes of assessment. Burden (Reference Burden, Kriegler and Englebrecht1996) argued that this can result in teachers, parents and administrators obtaining ‘useless information which they either find impossible to interpret, or which doesn't answer the questions that were required but they didn't bother to ask’ (p. 97). Burden referred to the kinds of questions that should be asked as the ‘why’ of assessment: essentially, why is the assessment being carried out? This specific question leads to many others; for example: Who wants information about this child? What kind of information is desired? In whose interest is the assessment being carried out? What are the gains and the adverse consequences of carrying out this assessment? (Burden, Reference Burden, Kriegler and Englebrecht1996; Cizek, Reference Cizek and Phye1997).

Gipps (Reference Gipps1994) outlined a number of purposes in the context of assessment in education:

[assessment] has to support teaching and learning, provide information about pupils, teachers and schools, act as a selection and certificating device, as an accountability procedure, and drive curriculum and teaching . . . [but] the prime purpose of assessment is professional: that is assessment to support the teaching/learning process. (pp. 1–3)

The approach of dynamic assessment, through the provision of examiner assistance (sometimes known as ‘mediation’), also aims to support the teaching and learning process, and tries to tackle some important questions; for instance: What strategies could be used to tackle the child's learning difficulties? What are his/her cognitive strengths and weaknesses? In what ways does he/she respond to assistance? Lidz (Reference Lidz and Carlson1992) argued that the aim of educational psychology assessment should be to help class teachers provide individualised programs for children:

The questions behind psychological assessment have tended to move away from such concerns as ‘How can we most appropriately sort and classify children?’ to ‘How do we teach this child?’ and ‘How can we help classroom teachers individualise their programmes?’ (p. 207)

Here Lidz refers to the relationship between psychological assessment and what happens subsequently regarding the child's learning. In what ways can assessment inform the next steps of the child's learning? When assessing a child, there is frequently an aim to link the findings of the assessment to the child's program of intervention; this is commonly referred to by teachers as ‘formative assessment’. Indeed, much of the philosophy underlying dynamic assessment shares common ground with the teaching approach of formative assessment (Yeomans, Reference Yeomans2008). Formative assessment is intended to have a subsequent, positive effect on a child's learning through the use of feedback and consultation. There has been increasing recognition that assessment should be used to support learning, rather than merely reporting a child's current, or past, achievement (known as summative assessment; Black, Reference Black1995; Glaser, Reference Glaser1990; Torrance Reference Torrance1989).

Dynamic assessment (DA) is considered a more recent development in the practice of educational psychologists, despite being promulgated as an alternative approach to psychological assessment for decades (Budoff, Reference Budoff1970; Feuerstein, Rand, & Hoffman, Reference Feuerstein, Rand and Hoffman1979; Guthke, Reference Guthke1982). A survey of 88 educational psychologists in the United Kingdom (Deutsch & Reynolds, Reference Deutsch and Reynolds2000) indicated that while most educational psychologists (EPs) were in favour of the approach, a common difficulty reported was how to move from theory to practice. In particular, EPs seemed to find the report writing aspect of dynamic assessment very challenging. The EPs reported that they often found it difficult to communicate the findings of DA and make the link to the classroom in terms of suggestions and recommendations for teachers and other staff. One might argue that if the suggestions and recommendations made on the basis of a dynamic assessment are not put into practice by those working daily with the child, it almost renders the assessment meaningless.

While the arguments in favour of using the DA approach are strong (Lauchlan, Reference Lauchlan2001), and indeed are recognised by educational psychologists, there remains insufficient evidence that it can change the nature of children's intervention programs significantly (Deutsch & Reynolds, Reference Deutsch and Reynolds2000; Elliott, Reference Elliott2003; Lauchlan & Elliott, Reference Lauchlan and Elliott2001; Yeomans, Reference Yeomans2008). There may be potential for the use of the DA approach in answering the more important questions described above; however, it has not yet realised that potential (Murphy, Reference Murphy2011; Yeomans, Reference Yeomans2008), mainly because there has been insufficient consideration of how to make DA meaningful in the classroom. Some have argued that there has been a lack of criticality by authors in the field (Burden, Reference Burden2002); however, it is argued here that there is little useful advice by authors in the field (possibly because most of the DA literature is written by academic researchers rather than practising educational psychologists) as to the most effective ways in which to feedback the results of the assessment in order to maximise such an impact on a child's learning. Alternatively, highly specific advice is provided; for example, recommendation of a specific program of intervention that will not be available in most circumstances, and moreover, the assessment will be based on several hours contact time, a situation which is simply not an option for most practising educational psychologists.

It is the issue of linking assessment to intervention that will be the crucial test of whether DA will continue to be used and incorporated in EPs’ everyday practice:

Unless there is greater emphasis placed upon informing intervention than on classification and selection, it is unlikely that most clinicians will consider DA sufficiently worthwhile to move away from existing assessment practices. (Elliott, Reference Elliott, Lidz and Elliott2000, p. 735)

It is this ‘greater emphasis on informing intervention’ that formed the basis of the practical approach presented here.

The resources and practical ideas to be discussed below emerged from the writer's work (in collaboration with a colleague, also a practising educational psychologist; Lauchlan & Carrigan, Reference Lauchlan and Carrigan2013) specifically using dynamic assessment approaches. The resources have been developed over a number of years as a result of working daily with children, teaching staff and parents and can be encapsulated under the heading ‘Improving learning through dynamic assessment’. However, the value of these materials in the wider context of psychological assessment has been recognised by other educational psychologists who have piloted the materials using more traditional assessment approaches.

The materials have been piloted by two local authority Educational Psychology Services in the United Kingdom. Several research studies have been undertaken on the piloting of the materials, that demonstrate empirical findings relating to the use of the approach, some of which have been published in peer-reviewed journals (see Elliott & Lauchlan, Reference Elliott and Lauchlan2000; Elliott, Lauchlan, & Stinger, Reference Elliott, Lauchlan and Stringer1996; Landor, Lauchlan, Carrigan, & Kennedy, Reference Landor, Lauchlan, Carrigan and Kennedy2007; Lauchlan, Reference Lauchlan1999; Lauchlan, Carrigan, & Daly, Reference Lauchlan, Carrigan and Daly2007). These studies demonstrate the link between the assessment and subsequent improvement in learning, including positive feedback from teachers and policy-makers regarding the usefulness of the approach.

While the rest of this article will refer to the practice of dynamic assessment, it should be acknowledged that the resources and ideas could also be valuable to those psychologists employing other assessment approaches.

Improving Learning Through Dynamic Assessment

Improving Learning Through Dynamic Assessment: A Practical Classroom Resource for Educational Psychologists (Lauchlan & Carrigan, Reference Lauchlan and Carrigan2013) provides a framework with four parts: Assessment, Feedback, Intervention and Review. For each of these elements, practical materials have been developed that can be used by educational psychologists and others in their practice of using dynamic assessment. The practical elements are as follows:

1. Assessment

• Materials: checklists of Learning Principles (cognitive and emotional).

• Aim: to be used as a practical aid to help with the recording of information during a dynamic assessment.

2. Feedback

• Materials (1): a proforma entitled a ‘Learning Profile’.

• Aim (1): to be used to summarise quickly and effectively the findings of a DA to parents and teaching staff.

• Materials (2): the Learning Principles adapted into simpler, child-friendly language, with accompanying graphic representations.

• Aim (2): to be used to feedback to the child following a DA.

3. Intervention

• Materials: a Bank of Strategies, which includes general tips, strategies, resources and activities.

• Aim: to map directly onto the two checklists (i.e., strategies and resources are provided for each of the learning principles).

In addition to this framework, training materials have been developed to help with the implementation of systemic work in dynamic assessment. These in-service training materials have been developed to train teaching staff in making them more aware of the approach, which in turn will help make the DA feedback more understandable and more likely to have an impact.

The child-friendly ‘Learning Principles’ and accompanying graphic representations can be used as training materials with children. A booklet/guide has also been developed, providing general background information on DA, which has been written in simple, clear, user-friendly language, and can be distributed to staff, parents and children when a DA has been undertaken. There now follows further details on each of the main elements of the approach to Improving Learning Through Dynamic Assessment.

Assessment

There are a number of learning principles that the assessor is aiming to observe during a dynamic assessment. These can be divided into cognitive skills (aspects of problem-solving behaviour) and affective (emotional) factors. Through the use of a collaborative environment between assessor and child (known as ‘mediation’), the aim is to bring about change in these learning principles. In other words, in what ways can the assessor enable change in the child's approach to learning during the assessment? For example, a child may be very impulsive at the beginning of the assessment; however, after intervention by the assessor to tackle this learning principle (perhaps through comments such as ‘Slow down, take your time, you know you do better when you stop and think about it first’), the child may make the transition from ‘other-regulated’ to ‘self-regulated’ (Wood Bruner, & Ross, Reference Wood, Bruner and Ross1976) and become more reflective as a result.

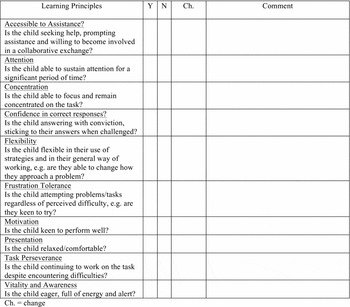

The idea to develop checklists of learning principles emerged from the increasing difficulty experienced when trying to record information during dynamic assessment. This was mainly because, in dynamic assessment, one is trying to intervene and provide ‘mediation’, as well as being an assessor. The checklists (see Figures 1 and 2) were based on the work of Feuerstein, Feuerstein, Falik, & Rand's (Reference Feuerstein, Feuerstein, Falik and Rand2002) list of deficient cognitive functions, and Tzuriel, Samuels, & Feuerstein's (Reference Tzuriel, Samuels, Feuerstein, Gupta and Coxhead1988) list of non-intellective factors. However, an essential difference is that the checklists have been worded positively, that is, what the child can do, rather than what the child cannot do. Moreover, the content of the checklists has been adapted, including adding some new learning principles, based on the writer's several years experience of using the dynamic assessment approach.

FIGURE 1 Checklist of learning principles (cognitive).

FIGURE 2 Checklist of learning principles (affective).

The information recorded on the checklists can be used directly to inform the feedback given to staff, parents and the child (viz-a-viz a learning profile that will be discussed below). It is recommended that the assessor prioritises around three learning principles that were deemed to be most important to the child's learning during the dynamic assessment. It is this process of moving from assessment to feedback that is a crucial part of dynamic assessment, and is now discussed.

Feedback

The idea of a Learning Profile (see Figure 3) was developed in response to feedback from teaching staff and parents who struggled to put into practice the suggestions and recommendations that were made in the dynamic assessment reports provided. These reports tended to be rather lengthy accounts of the assessment, sometimes littered with jargon and concepts that teachers and parents found difficult to comprehend (e.g., cognitive modifiability, mediated learning, non-intellective factors).

FIGURE 3 Learning profile.

Instead of writing up to three or four pages of text on the cognitive skills and affective factors of the child's learning, it was felt to be more meaningful and valuable for staff and parents to transform the information gathered during the dynamic assessment into a one-page profile of the three most important factors that were highlighted during the assessment. The words most important are significant because the three learning principles highlighted could be those skills that were most amenable to change during the dynamic assessment, and could therefore be encouraged more in the classroom. This is in accordance with Feuerstein's theory of structural cognitive modifiability (Feuerstein et al., Reference Feuerstein, Feuerstein, Falik and Rand2002). Alternatively, there may be a focus on those learning principles that were difficult to modify during the assessment, and that therefore require further, significant investment. Or, indeed, the assessor may decide to focus on the learning principles that were clear strengths in the child, that is, were demonstrated throughout the assessment. It may the case that such strengths are being underused in their everyday classroom activity and should therefore be promoted.

On the right-hand side of the learning profile are some ideas or activities that are suggested to help address or encourage the most important factors that were highlighted. These ideas are taken from a ‘Bank of Strategies’ that will be described in further detail below in the section ‘Intervention’.

The learning profile can be used in different ways. For example, it could be completed at a review meeting with teaching staff and parents, where a consultation approach could be used to identify three significant areas of the child's learning, as well as corresponding ideas and suggestions for intervention.

The learning profile is intended to be a practical resource that can be used by the child's teacher, parents, auxiliary staff, learning support staff, as well as the child himself/herself. Moreover, writing a learning profile should be less time consuming than writing a three- or four-page detailed report.

It could be argued that focusing on only three of the many cognitive and affective factors observed during the assessment may not be a full account of the child's learning. However, the learning profile is intended to be a more focused report to make it easier to enable change, as it is easier to implement an action plan that focuses on only a few issues in a child's learning rather than trying to address many different issues simultaneously. Moreover, the learning profile can be reviewed at suitable intervals (e.g., every 6 months — see below) to ensure the profile is being effective in addressing the issues highlighted, or whether there needs to be any changes to the profile.

Another important factor often overlooked by those working in the dynamic assessment field is the inclusion of children in the feedback process following an assessment. In trying to change some aspects of the child's learning style and improve the child's teaching and learning, it is commonly the case that those attending a feedback meeting (e.g., educational psychologist, teacher, support for learning staff and parents) do not include the child himself/herself in this feedback. Often this is because it is felt that the language used in such a feedback session may be too difficult for the child to understand, and that there is therefore little point in including the child. For example, it may be that the child's reading ability would not enable them to access the language in the report which has been written following a dynamic assessment.

It is argued here that neglecting the role of children in trying to change their own learning style is a gross misrepresentation, and potentially harmful to the success of an intervention plan. The learning principles have been ‘translated’ into much simpler, child-friendly language (see Figure 4) and with each learning principle depicted by a graphic representation to aid the child's memory, thus helping the intervention process.

FIGURE 4 Child friendly learning principles — cognitive and affective.

Intervention

As discussed above, the intention of the learning profile is not only to feedback those factors that appeared to be most important to the child's learning during the dynamic assessment, but also to provide suggestions and recommendations to tackle or encourage these factors.

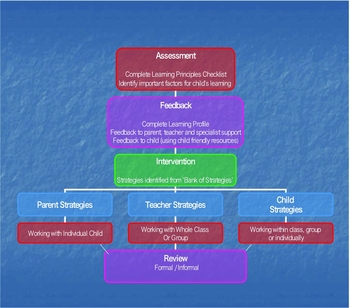

After using the dynamic assessment approach for several years, the author had developed some ideas and suggestions that could be made to teaching staff and parents on the basis of the information gathered during the DA. However, this fairly limited list of strategies and suggestions was quickly exhausted and it was felt that a more extensive ‘Bank of Strategies’ was needed, to which the psychologist could refer when feeding back the dynamic assessment results. Ideally, the intention was to build up strategies/recommendations for each of the learning principles that were delineated in the checklists described above. Thus, the aim was to create a much simpler framework from the recording of information during the assessment (via the two checklists) to the feedback meeting (via the learning profile) and then to the intervention program (via the bank of strategies). Figure 5 provides an overview of this process and the relationship between the four elements of Improving Learning Through Dynamic Assessment, that is, assessment, feedback, intervention and review.

FIGURE 5 Graphical representation of the four key elements of Improving Learning Through Dynamic Assessment: assessment, feedback, intervention and review.

In building up a bank of strategies, a number of different interventions have been developed that can be used at an individual level with the child, at a group level, and at a whole class level. Moreover, the bank of strategies includes not merely some hints, but also activities, games and resources that can be tried with the child at home, as part of a small group, or as part of the whole class.

Review

The last part of the staged process is to review the learning profile and the suggested intervention strategies. This is a very important part of any assessment since not every strategy suggested will work for every child, therefore it is necessary to review any intervention to ascertain whether or not it has been effective. If the strategies tried have indeed been effective for the child, then it is important for those involved to provide positive feedback. If not, then it is important to highlight this and the reasons why, and where necessary, discuss alternatives. As stated above, it is possible that after a period of 6 months that some positive changes have already occurred in those learning principles highlighted by the profile. Thus, after a review of the original learning profile, it may be that other learning principles, perhaps observed during the original assessment, can be included in the newly modified learning profile. Alternatively, it may be that those learning principles highlighted in the original learning profile have not changed significantly in the time since the last review, and that there may need to be changes made to the suggestions/recommendations designed to encourage those said learning principles. It may or may not be necessary to include the educational psychologist in the review of the learning profile.

Training Materials

It is argued here that another essential element in making dynamic assessment effective, and in making it more meaningful in the classroom, is to raise awareness of the approach to classroom teachers and those working daily with the children and young people. In-service materials have been developed that transform the somewhat complex language of dynamic assessment and its background theories and concepts into more accessible and comprehensible terms, to make it more meaningful for class teachers. These materials have already been piloted in several primary schools, and the response to this training has always been of a very positive nature.

The intention in providing in-service training in dynamic assessment to schools is to aid the process of ‘making DA meaningful in the classroom’, as it is only through cooperation and collaborative working with teaching staff that the ideas and concepts of DA can be implemented in the classroom.

The in-service training materials were based on the work done in completing a general guide to dynamic assessment, which was published by South Lanarkshire Council in the UK (SLC, 2003). This guide is written in clear and simple language and is distributed to parents and teachers when a psychologist is feeding back the results of dynamic assessment. It is a common criticism of the dynamic assessment approach that the literature is often full of complex language and unnecessary jargon, which serves to cloud the ideas and concepts rather than illuminate them for practitioners in schools and parents (Buchel & Scharnhorst, Reference Buchel, Scharnhorst, Hamers, Sijtsma and Ruijssenaars1993; Deutsch & Reynolds, Reference Deutsch and Reynolds2000).

It is also possible to deliver training to children and young people. The child-friendly learning principles (and their graphic representations), alongside the activities and worksheets from the Bank of Strategies, could be used to guide group work with children, to help in general terms their teaching and learning in the classroom.

Conclusion

The four strands to the dynamic assessment approach outlined above form the basis of Improving Learning Through Dynamic Assessment. It is intended to provide a clearer relationship between the assessment process and the subsequent feedback to staff, parents and children, which then informs a plan of intervention and review. The practical materials that accompany this approach, some of which are attached to this article, have been collated and published as a resource (Lauchlan & Carrigan, Reference Lauchlan and Carrigan2013). The resource encapsulates this approach of linking assessment, feedback, intervention and review. It is intended to help educational psychologists and other professionals who are trying to implement the potentially powerful ideas and concepts underlying dynamic assessment, but who are given little guidance in making the transition from theory to practice. It is also hoped that the resources and ideas may also be considered valuable by psychologists who practise assessment approaches other than dynamic assessment.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Donna Carrigan for the significant contribution she has made to to ideas presented in this article. Some of the images presented in this article have been reproduced by kind permission of Jessica Kingsley Publishers, taken from Improving Learning Through Dynamic Assessment: A Practical Classroom Resource that will be published in March 2013 and available from www.footprint.com.au<http://www.footprint.com.au/>. ISBN: 9781849053730