Modern understanding of the production and dissemination of Western twelfth- and thirteenth-century polyphony is largely constrained by the paucity of surviving complete manuscript sources and the mare magnum of fragments scattered worldwide in libraries. While France, and Paris in particular, are generally considered the cradle of what is conventionally and meaningfully named ‘Notre-Dame’ polyphony, this repertory travelled far beyond the boundaries of its original place, spreading through most of today’s Europe. Two out of the four large extant collections transmitting the repertory were not compiled in Paris or France, but in Scotland in the 1230s (W1)Footnote 1 and Castile between approximately 1240 and 1250 (Ma).Footnote 2

The largest manuscript collection of twelfth- and thirteenth-century polyphony and the ‘Notre-Dame source’ par excellence is the Florence manuscript (F), compiled in Paris sometime between 1240 and 1250,Footnote 3 possibly for the dedication of the Sainte-Chapelle, the chapel of the Parisian royal palace on the Île-de-la-Cité, which took place on 26 April 1248;Footnote 4 its present location in Florence dates back to the fifteenth century, when it entered the library of Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici (1416–69), perhaps as a gift from Louis XI.Footnote 5 So far, F retains its uniqueness as the only complete, almost all-inclusive and central ‘Notre-Dame source’, while the thirteenth-century Parisian production of comparable books of polyphony – an activity that might have already been in place in the first quarter of the centuryFootnote 6 – can only partially be reconstructed, like a puzzle with a number of missing pieces. The subject of the present study is a so far neglected piece of this fragmented picture, which contributes to a deeper understanding of the place polyphonic music occupied in the emergent commercial book production of thirteenth-century Paris.

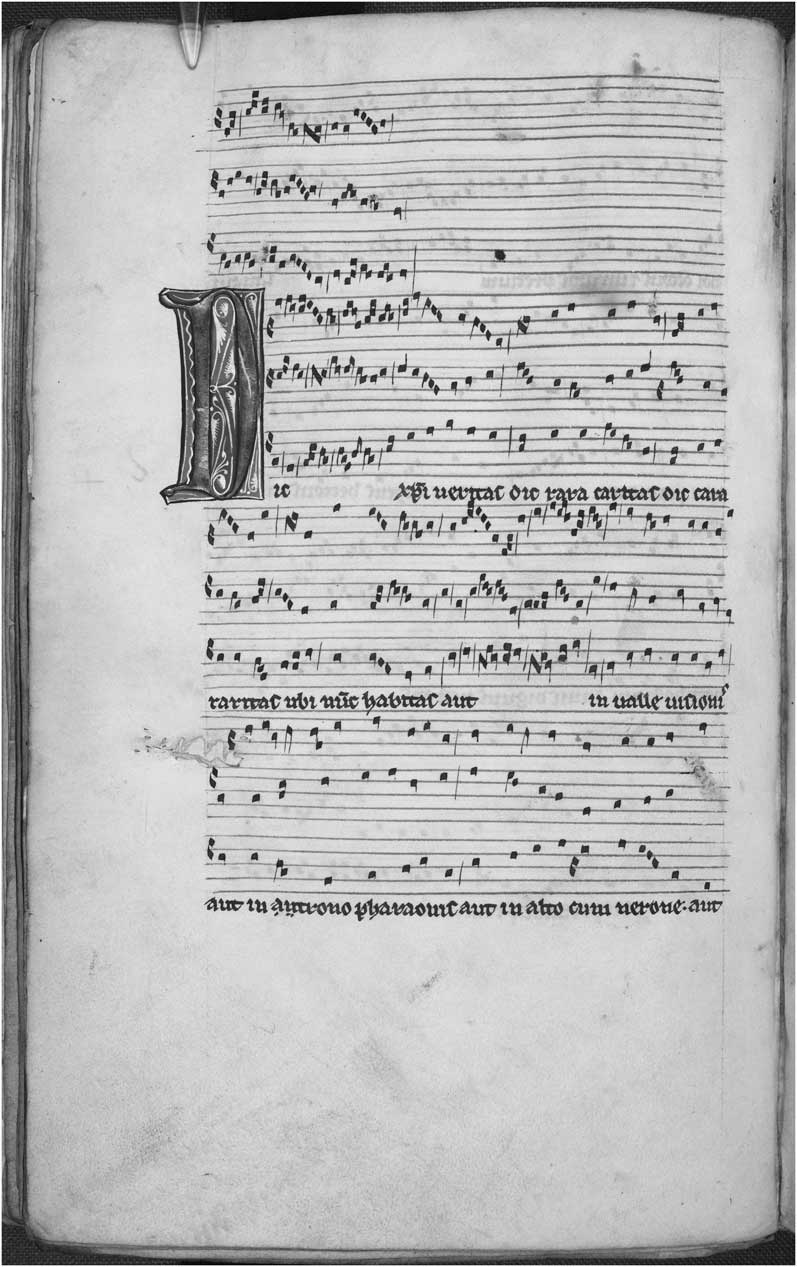

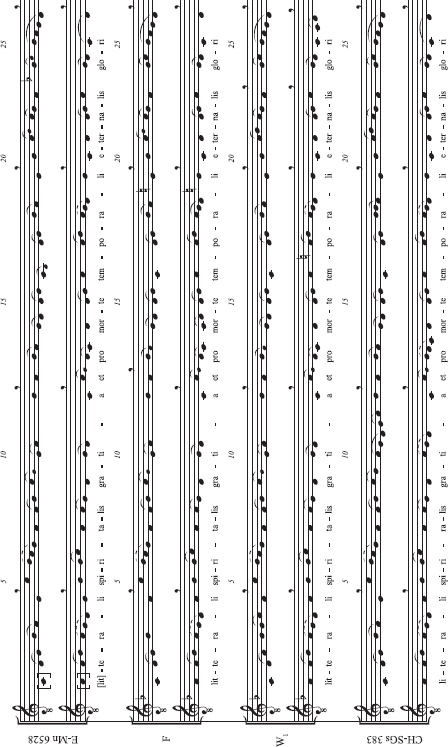

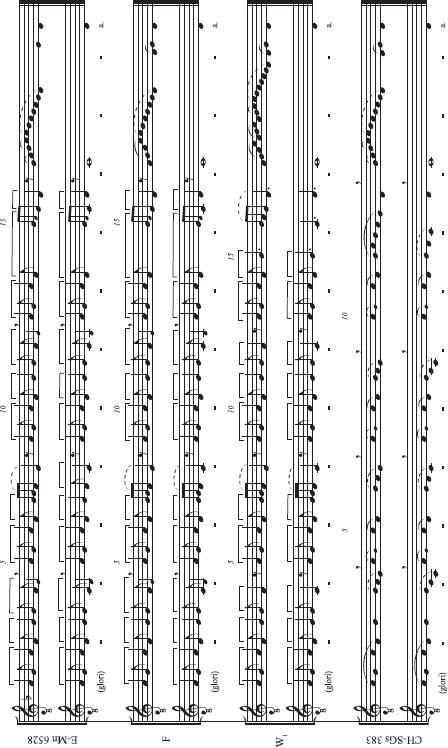

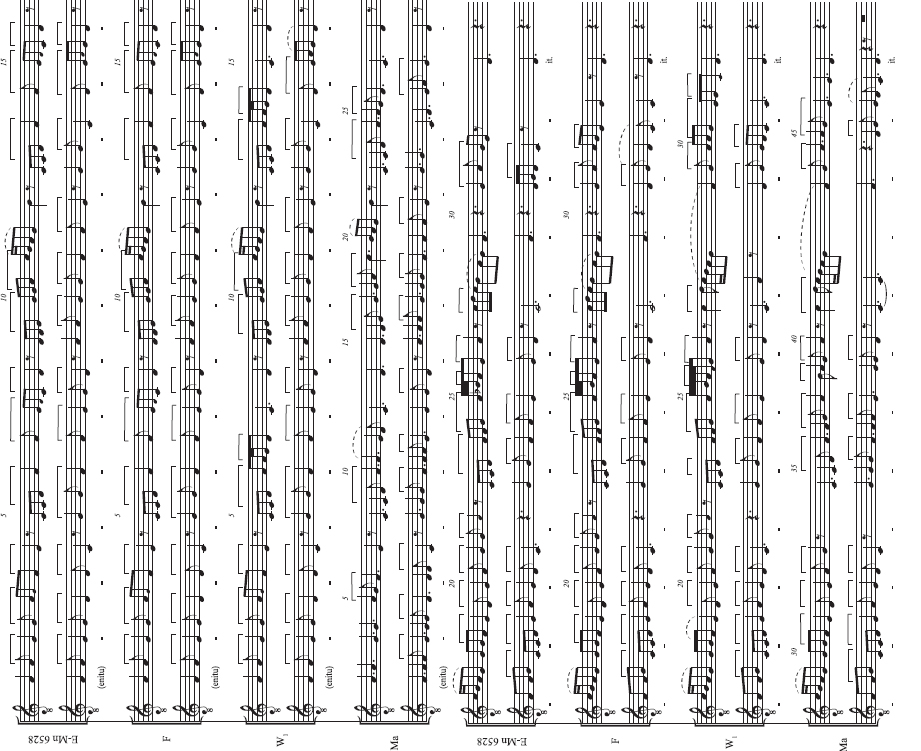

The source consists of three fragmentary folios from the same Ars antiqua manuscript that were attached to the binding of manuscript E-Mn 6528 – a copy of Priscian’s Ars grammatica. The only folio that is currently fully visible (see Figures 1 and 2) contains two fragmentary polyphonic conducti known from other sources: Legem dedit olim Deus and Lux illuxit gratiosa (see Table 1). David Catalunya recently noticed that this fragment displays a number of codicological and musical features that are strikingly similar to those found in F: both sources share format and mise-en-page, make use of similar styles of script, notation and pen-work decoration, transmit the pieces in the same order,Footnote 7 and present virtually identical musical readings.Footnote 8 The present article provides a detailed account of these features and explores the hypothesis that the musical fragment in E-Mn 6528 originated in the same Parisian workshop that produced F. Ars antiqua sources that can reasonably be recognised as products of the same workspace are extremely rare: so far, the only known case was the second section of the composite manuscript LoA, which Mark Everist suggests originated from the same workshop in which F was compiled.Footnote 9 The physical characteristics and musical content of E-Mn 6528 provide further evidence for the standardised production of polyphonic books in thirteenth-century Paris, and therefore contribute to our understanding of the reproduction and dissemination of Notre-Dame polyphony.Footnote 10

Figure 1 E-Mn 6528: Ars antiqua Fragment 1, recto (back flyleaf). © BNE

Figure 2 E-Mn 6528: Ars antiqua Fragment 1, verso (back flyleaf). © BNE

Table 1 Contents and concordances of the back flyleaf of E-Mn 6528 (Fragment 1)

* Both new and old foliations of W1 are provided; the former, which was added after the loss of a number of leaves, is given in brackets.

The existence of the Ars antiqua fragment in E-Mn 6528 was first acknowledged in 1910 by Friedrich Ludwig, who had received a description from Wilhelm Meyer.Footnote 11 At that time, however, the musical folios were still glued to the cover, and therefore only a section of the conductus Lux illuxit was visible. Two decades later, Higini Anglès briefly mentioned E-Mn 6528’s pastedown and suggested that its musical notation was connected with that of W1.Footnote 12 In 1946, Anglès and Subirà included the fragment in the catalogue of musical manuscripts of the Biblioteca Nacional de España, without providing any significant additional information.Footnote 13 More recently, Juan Carlos Asensio saw the pastedown when it had been detached from the back cover and reported the presence of both conducti.Footnote 14 Additionally, Maricarmen Gómez Muntané suggested that the fragment must have belonged to an ‘important’ collection of conducti, given ‘the quality of the copy’.Footnote 15 Nonetheless, neither Asensio nor Gómez Muntané performed a detailed examination of E-Mn 6528, as their works concerned a different topic and entailed a larger scope respectively. A thorough discussion of the resemblance of this fragment to F and its implications for the knowledge of Parisian book production in the thirteenth century has so far been lacking.

CODICOLOGICAL AND PALAEOGRAPHICAL OBSERVATIONS

The Host Manuscript and its Binding

E-Mn 6528 contains the first sixteen books of Priscian’s Ars grammatica.Footnote 16 The body of the manuscript consists of 123 folios measuring approximately 230 × 140 mm (ruled frame: 187 × 86 mm), a narrower format than usual. The codex was rebound in the fifteenth century; the binding structure, as well as the flyleaves and pastedowns that were attached to the new cover, will be discussed below.

A number of codicological and palaeographical features suggest that the host manuscript may date to the twelfth or very early thirteenth century at latest. All the quires of the book begin consistently with the hair side of the parchment and the text is always entered starting from above the top line of the ruled frame: both features are typical of twelfth-century Western manuscripts; they start to be reversed in books produced before the mid-thirteenth century.Footnote 17 The script of the main text, most likely the work of a single scribe, also points to the twelfth century: the lack of fusion and overlaps of letters and the use of very short ascenders and descenders are typical of a twelfth-century pre-Gothic hand.Footnote 18 In addition, the forms of some individual letters are commonly found in twelfth-century Iberian manuscripts. Two forms of a are used, one with the top of the shaft turning over to the left, and another, common in the Iberian Peninsula, drawn with a large lobe that makes it look like a single-compartment a. Two types of d appear in the text: one is vertical (a vestige of Carolingian script), the other is uncial with a curved ascender to the left that occasionally concludes with a small stroke curving to the right; the concurrence of both types is not uncommon in twelfth-century books and, in E-Mn 6528, are used in succession within words with double ds, a feature that appears in Iberian and southern French manuscripts. The same phenomenon can be observed for the forms of f and r, both of which extend slightly below the baseline, a feature found in German and Iberian manuscripts of the twelfth century.Footnote 19

The decorated initials of the host manuscript do not add much information to the foregoing palaeographic analysis. The decoration work was carried out by more than one individual at different times; some initials are in twelfth-century style (see, for example, fols. 90r, 96r, 107r); others were clearly added later in the thirteenth century (see fols. 7r, 23r, 115r). In any case, these styles and types of decoration are frequently found in manuscripts from the Iberian Peninsula, France, and elsewhere.Footnote 20

Whereas the palaeographical and ornamental features do not rule out a possible Iberian origin of the host manuscript, we can affirm with a high degree of certainty that the codex was rebound in fifteenth-century Spain. The current cover (see Figure 3) is an interesting exemplar of mudéjar binding, typical of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Iberia, and characterised by the use of Sienna tanned goatskin decorated with circles, braided shapes and other geometric patterns. The term mudéjar derives from the Arabic mudayyan, and refers to people of Islamic faith who did not convert to Christianity after the Reconquista. The mudéjar art, indeed, resulted from the combination of coexisting Islamic and Christian traditions within the Iberian Peninsula.Footnote 21 The main centres of production of this kind of binding were Toledo and Barcelona, followed by Valencia, Zaragoza, Salamanca, Guadalajara, Burgos, Segovia and Seville among others.Footnote 22 E-Mn 6528’s cover is described in the catalogue of mudéjar bindings of the Biblioteca Nacional de Madrid.Footnote 23 Nonetheless, although its mudéjar style and, therefore, Iberian origins are firmly established, its precise provenance remains elusive.

Figure 3 E-Mn 6528: Front cover. © BNE

The provenance of the twelfth-century grammar book and its fifteenth-century binding cannot be determined with further precision.Footnote 24 The Biblioteca Nacional de España does not preserve any record of its acquisition, a fate shared by a number of medieval codices now in Madrid.Footnote 25 Paradoxically, the origins of the thirteenth-century fragment of polyphony inserted into the binding of E-Mn 6528 can be delineated in more detail, given its shared features with F.

The Ars antiqua Fragment

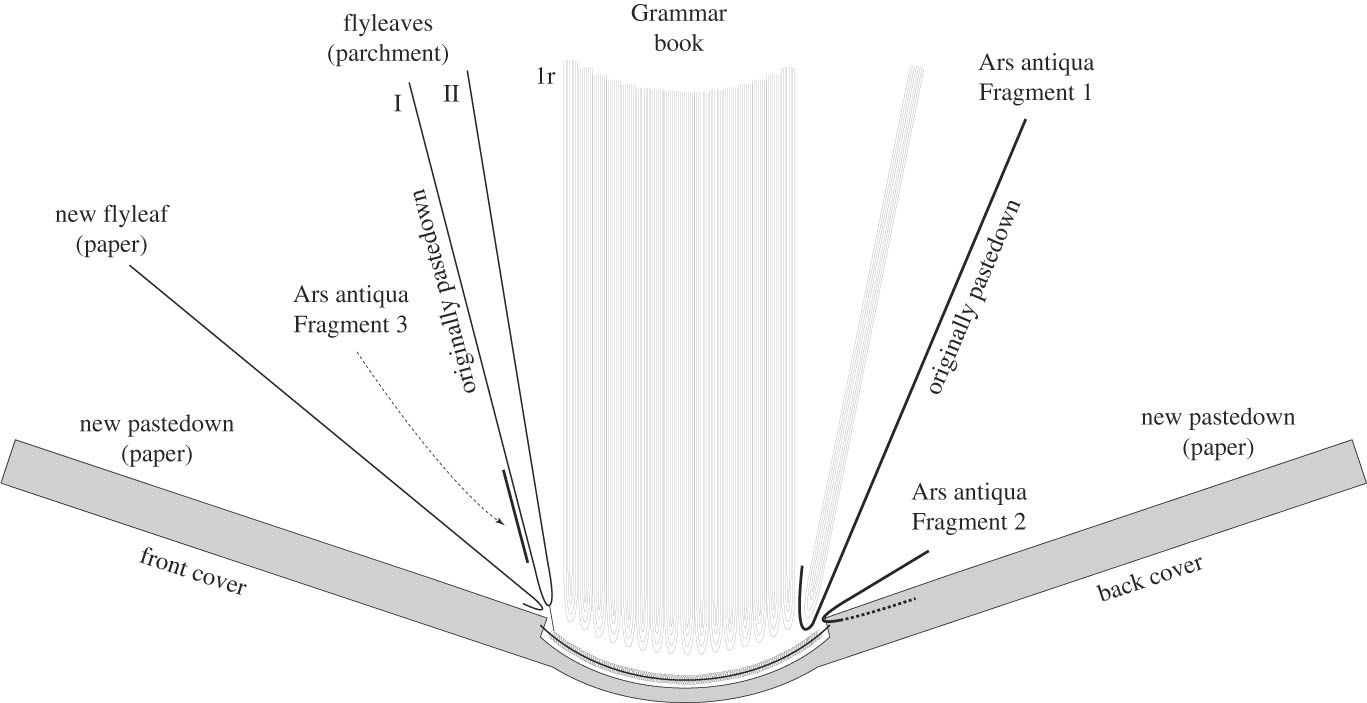

E-Mn 6528’s fifteenth-century binding was originally provided with parchment pastedowns, which were detached from the front and back covers during restoration work that took place in the Biblioteca Nacional in the late twentieth century. Figure 4 shows a diagram of the current structure of the binding. The fully visible Ars antiqua folio, referred to as ‘Fragment 1’, was inserted upside down and glued to the back cover as a pastedown. ‘Fragment 2’, however, retained its upright position and was inserted as an inner reinforcement before Fragment 1 was pasted down; Fragment 2 continues inside the back cover and the only portion of the folio now visible is the outer margin of the original folio (see Figure 5).Footnote 26 The parchment bifolio attached to the front cover has a third fragment from the same source pasted to it (‘Fragment 3’, see Figure 6),Footnote 27 and also contains an offset of musical notation from a fourth, now lost, fragment that most likely acted as an inner reinforcement inside the cover.Footnote 28

Figure 4 E-Mn 6528: Codicological diagram

Figure 5 E-Mn 6528: Ars antiqua Fragment 2. Reproduced with the kind permission of the BNE

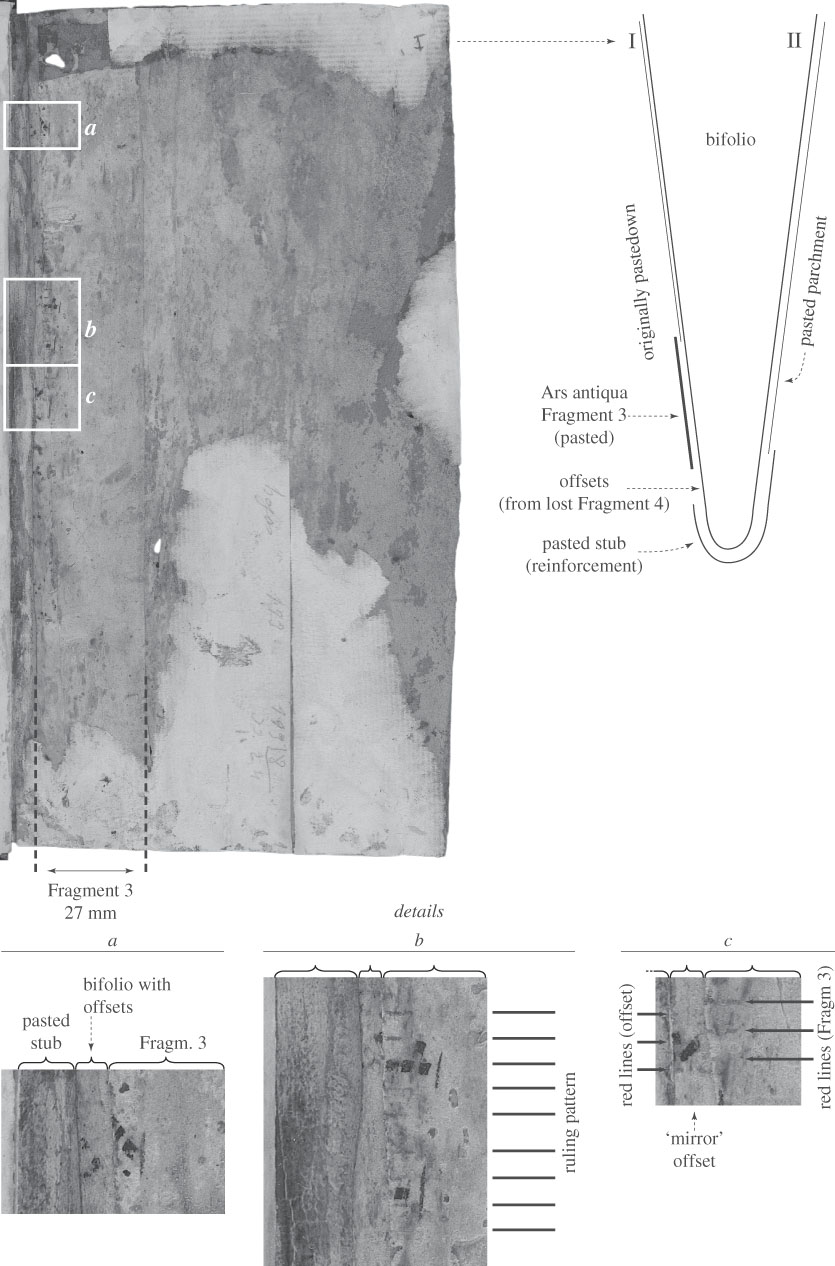

Figure 6 E-Mn 6528: Ars antiqua Fragment 3. Reproduced with the kind permission of the BNE

The bookbinder cut off the left side of Fragment 1’s original bifolio, and then inserted the last gathering of Priscian’s book into the remaining original fold of the mutilated bifolio (see Figure 4). Once glued to the back cover as a pastedown, Fragment 1 was trimmed in order to make it fit the format of the cover. However, whilst the outer margin of Fragment 1 thus became narrower, that of Fragment 2 was preserved in its entirety (see Figure 5). Fragment 2 displays the upright corner of ruled frame, six guiding lines for the text, and the pricking marks used to rule those guiding lines. On the verso of this Fragment 2, the letters ‘e’ and ‘m’ are placed next to the folio’s edge. Carmen Julia Gutiérrez suggests that these are guide-letters indicating the minor initials to be inserted by the decorator, and that Fragment 2 might originally have belonged to a fascicle containing clausulae, rather than conducti. Similar guide-letters are occasionally noticeable in F, both in outer and inner margins (see, for instance, fols. 147r and 327r–v). A typical conductus section in F would not display many minor initials per folio, but fascicles transmitting clausulae would have the same initial letter repeated in three or more consecutive systems (lines), as occurs, for example, on fol. 151r, where the initial letter ‘m’ for Manere is found in three consecutive systems.Footnote 29 The fact that the ruling pattern of Fragment 2 consists of five lines for the upper voice but only four lines for the lower voice – the typical layout for two-part pieces based on liturgical tenors – further supports this hypothesis (see Figure 5, detail a).Footnote 30

Both the pricking marks and the guide-letters were obviously meant to be trimmed off. Pricking marks are not visible in F and LoA, and the guide-letters in the Madrid fragment are placed right behind them. Also noteworthy is that the folio edge of Fragment 2 has a careless, curved contour, further suggesting that at least this section of the original manuscript remained untrimmed.

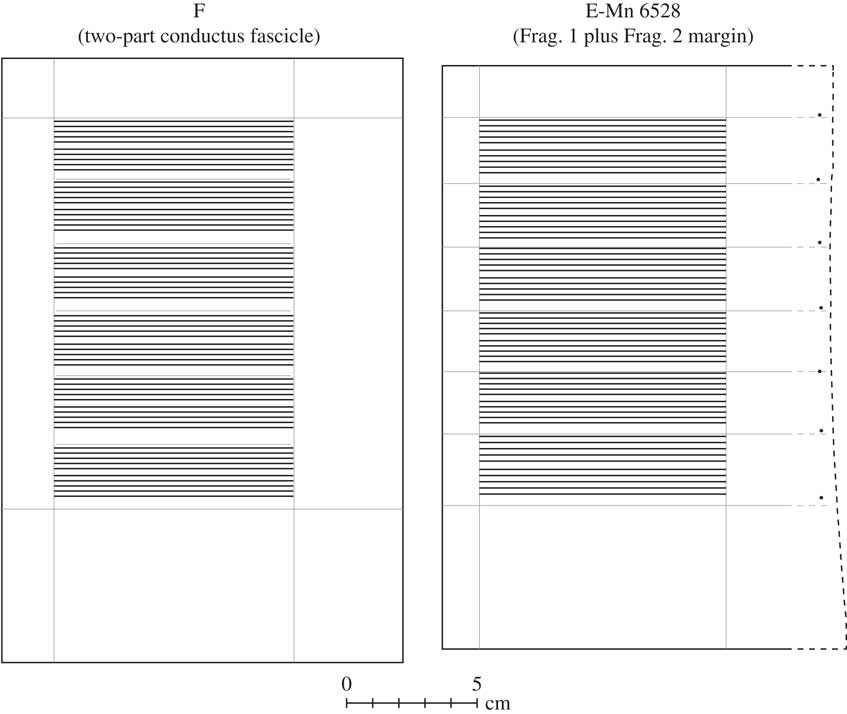

Fragment 1 currently measures 225 × 127 mm, with a ruled frame of 148 × 92 mm, and an outer margin some 25 mm wide. The fully preserved outer margin of Fragment 2, however, ranges between 40.5 and 47 mm (the folio has a curved edge). This indicates that the original Ars antiqua manuscript was around 20 mm wider – and, possibly, also slightly longer – than the current size of Fragment 1. These sizes roughly correspond those of F, the largest of the main Ars antiqua sources, which measures 232 × 157 mm and has an outer margin of around 40 mm (see Figure 7).Footnote 31 Moreover, the high-quality parchment of the fragment is akin to the fine one used for the Florence manuscript; it is thin (approximately 0.3 mm), flexible, and consistently white.Footnote 32 The type of lead pen used to rule the writing frame and text guiding-lines is very similar in the two sources. Perhaps the only substantial divergence in the preparation of the parchment of the two sources is that, whilst in F the text guiding-lines rarely continue over the outer margin, in E-Mn 6528 they do so more frequently.

Figure 7 Format and mise-en-page of manuscript F and E-Mn 6528

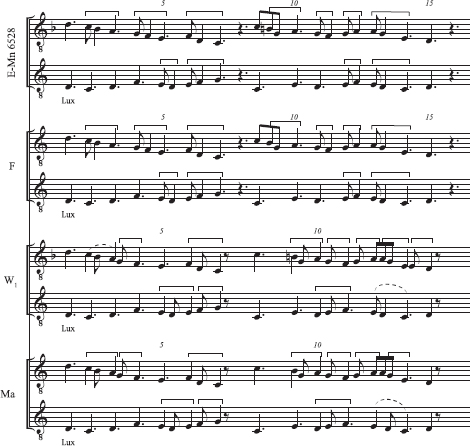

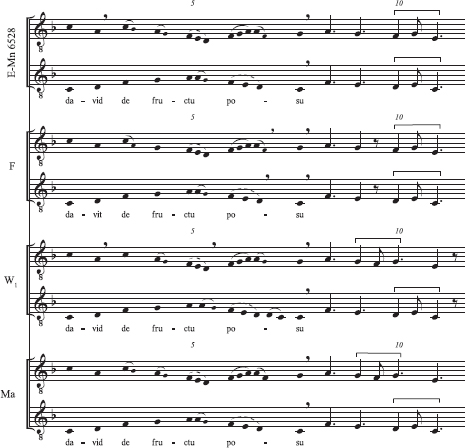

Yet, even more significant is the perfect match of the mise-en-page of the Madrid fragment with that of manuscript F: the ruled frames are 148 × 92 mm and 149 × 92 mm (average) respectively.Footnote 33 Obviously, this difference of a millimetre in height should not be taken into consideration, given that the same degree of discrepancy is found within F.Footnote 34 In both sources, the frame accommodates six two-part systems of red-coloured staves which have an average height of 10 mm.Footnote 35

Identical mise-en-page was, as mentioned above, the principal evidence presented by Mark Everist to suggest that the Ars antiqua section of LoA and manuscript F were prepared in the same workshop.Footnote 36 Everist hypothesised the use of a common ‘template’ for the pricking, which led to exact similarities in the ruling, and argued that a mere ‘imitation’ of a pre-existing format would have occasioned considerable differences; he presented W1 as a clear example of an attempt at imitating the format of contemporaneous Parisian manuscripts.Footnote 37 The evidence presented above suggests that E-Mn 6528’s fragment went through a very similar preparation process as F and LoA, which prompts one to wonder whether the same hypothetical template was used in the three manuscripts.

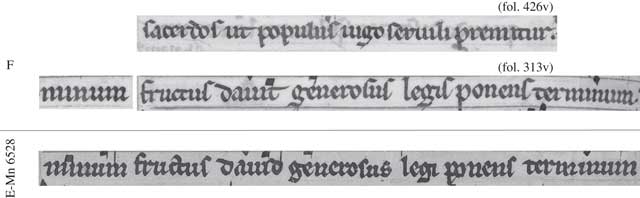

There is, in fact, further palaeographical evidence that ties the Madrid fragment and F together. The text script of the two sources is extremely similar in many details (see Figure 8). The type of script is a northern thirteenth-century littera textualis, characterised by the use of double-compartment a, ascenders without loops and flat on the top, and straight f and s that do not descend below the baseline.Footnote 38 This type of script results from an accurate and all-but-rushed ductus that produces easily legible letters, neatly separated from one another, and with a very regular module. In both sources the size of minims is approximately 3 mm, and most of the individual letters are written in exactly the same fashion: the double-compartment a has an open upper bow; the limb of h extends below the baseline; medial r appears in both straight and round forms; straight s appears in both medial and final position with its foot turning upwards to the right; round s is also occasionally used at the end of a word; t is very short and its shaft barely extends above the head-stroke; x is written drawing two diagonal strokes, the one going from the top right to the bottom left, displaying an elongated descender approached with a clockwise short stroke made with the full width of the nib and then proceeding downwards in a descending hairline. In F, the letter d is often drawn in its uncial form with an elongated shaft sloping to the left. Nonetheless, certain calligraphic features of the Madrid fragment, such as the shorter shaft of the letter d, are also found in F’s monophonic fascicle (see, for instance, F, fol. 426r–v).

Figure 8 Comparison of text script in F and E-Mn 6528. Reproduced with the kind permission of the MiBACT and the BNE

Only a few, subtle calligraphic differences between F and the Madrid fragment suggest that the two manuscripts were copied by different hands. Unlike in the Madrid fragment, the lower lobe of the letter g in F always has a shaft sloping down to the left. The loops of the long s are longer and more open in F than in the Madrid fragment. The Madrid scribe took the care of adding a diacritical stroke above the letter i in order to distinguish it from adjacent u minims – though not from adjacent m or n minims – while the scribe of F rarely used the diacritical stroke, and on occasion placed it above i next to m and n. It is of course impossible to determine the large-scale scribal variability of the Madrid copyist by analysing only one folio. Yet as it seems, the text scribes that worked on the Madrid fragment and F were two individuals trained in the same ‘school’.

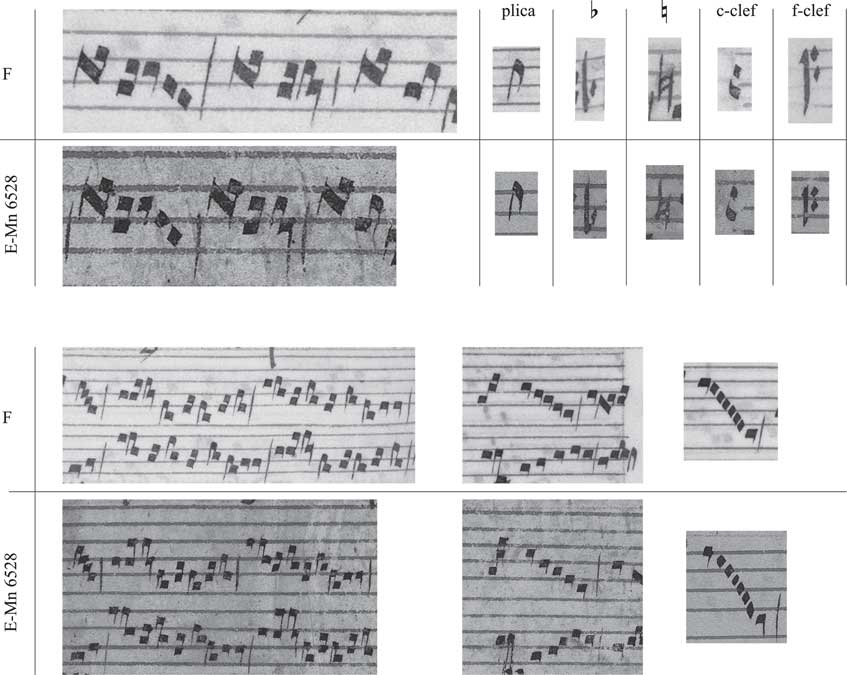

Essentially the same observation holds for the musical notation of E-Mn 6528 and F: the music script is so remarkably similar in the two sources that it is sometimes hard to distinguish two different hands (see Figure 9).Footnote 39 This music script is characterised by the short downward stems of the single notes, the stems of binary and ternary ligatures are often longer, and those of the porrectus usually extend slightly above the upper left corner of the oblique shaft. The square note-heads are drawn with a slight inclination of the pen’s nib to the right, which forms an angle ranging between 10° and 14° with respect to an imaginary line perpendicular to the stave. The nota plicata is drawn in two pen strokes, also with a slight inclination. The diamond-shaped notes, on the contrary, have their vertical axis perpendicular to the stave. Many other elements, such as the C-clef and the accidentals, look mostly identical in the two sources. The F-clef, however, looks significantly different in the two sources.Footnote 40 In the Madrid fragment, the vertical stem is rather thick and the strokes on its right are positioned on the G and E spaces of the stave, while in F the stem is thinner and the strokes are placed on the A and F lines.

Figure 9 Comparison of music script in F and E-Mn 6528. Reproduced with the kind permission of the MiBACT and the BNE

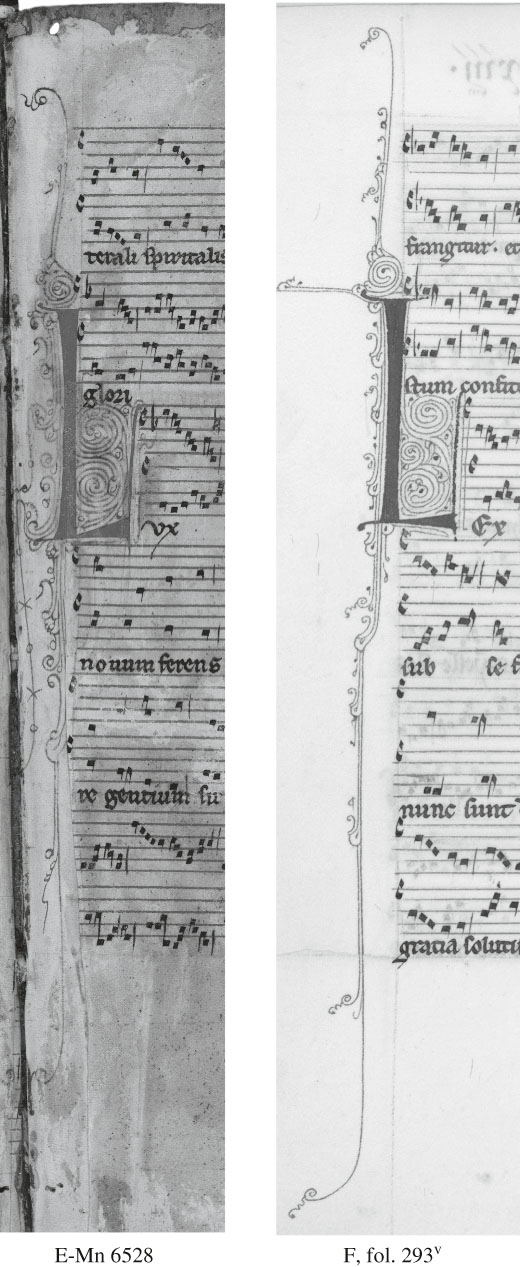

The pen-flourishing decorations of the Madrid fragment and manuscript F are more easily distinguishable as the work of two individuals, even though they clearly belong to the same tradition. The elaborated filigree initials include the same type of components, which are fairly common in thirteenth-century French manuscripts: spirals, ‘palmettes’, ‘extended fans’, flourish stalks with bulbs and ‘paws’, and long flourishes with curled tips.Footnote 41 Practically all the principal ornamental components of the Madrid fragment are also present in F, although not always used with the same frequency. The conductus Lux illuxit gratiosa in F begins at the top of the page, while in E-Mn 6528 it begins in the third system. The position of the initial within the page affects the design of its filigree. The conductus Lex honus importabile (F, fol. 293v) also begins in the third system and, therefore, the comparison of its decorated initial with that of Lux illuxit gratiosa in E-Mn 6528 is more pertinent. The two capital letters L are essentially identical in shape and the pen-flourishing decorations have a very similar overall design (see Figure 10). The ‘extended fan’ component beside the letter, however, is less frequent in F (see Figure 11b). The curled tip of the long flourishes is usually adorned with a small wave in F, while E-Mn 6528 displays a flower (Figure 11d). The bulb that articulates the descending flourish stalk is wider in E-Mn 6528 than the average in F (Figure 11e). The decorator at work in F tended to elaborate rather intricate spirals in the initials’ infillings, yet the type of spiral is essentially the same in the two manuscripts (Figure 11g).

Figure 10 Pen flourishing decoration in F and E-Mn 6528. Reproduced with the kind permission of the MiBACT and the BNE

Figure 11 Pen flourishing decoration in F and E-Mn 6528 (details). Reproduced with the kind permission of the MiBACT and the BNE

The codicological and palaeographical similarities between the Madrid fragment and F inevitably bring the above-mentioned manuscript LoA back into the picture. While the conductus flyleaf in E-Mn 6528 displays features whose resemblance to F go well beyond an identical ruling pattern, LoA presents a number of divergences from F. To begin with, the script in LoA, however still clearly recognisable as a thirteenth-century littera textualis, has – despite having the same allocated space for the text as in F – a smaller module and is more angular when compared to the other two sources,Footnote 42 leaving very little doubt that a different scribe is at work here (see Figure 12). The same can be said about the notation in LoA: it shares some similarities with that of F, but is undoubtedly the work of a different hand.Footnote 43 In addition, LoA was not decorated with elaborate filigree initials; it received far less intricate and quite ordinarily drawn initiales champies.Footnote 44

Figure 12 British Library, Egerton 2615 (LoA), fol. 87v/88v (older/newer foliation). © British Library Board

Given the shared features between the Madrid fragment and F, it is tempting to assume that the former was originally part of a book that did not differ much in volume, artistic ambition and scope from its Florentine counterpart, especially given the likelihood that the manuscript transmitted not only conducti but also clausulae and organa, and possibly other conventional Ars antiqua genres such as motets. The question of how the manuscript reached Spain will be addressed in the last section of this article.

In any case, the evidence discussed so far suggests that the Madrid fragment could have originated in the same Parisian workshop that produced F. This raises the question of whether one source was copied from the other, or they were both copied from a common exemplar. In order to shed light on this question we must analyse the musico-poetical transmission of the musical content of the Madrid fragment in all its extant sources.

TRANSMISSION

The textual and musical material available in E-Mn 6528, consisting of the final cauda of Legem dedit olim Deus and a great part of Lux illuxit gratiosa, allows partial comparison with other sources. Such comparison is nevertheless rather revealing.

First, it will be helpful to examine the textual transmission. The text of Legem dedit olim Deus in E-Mn 6528,Footnote 45 compared with all other extant sources of the poem, is given below (all abbreviations have been expanded and identified with the use of italic font; bold signals variants; lacunae are indicated with square brackets). In this case, all readings are essentially identical, even though it can be noted how E-Mn 6528 and F make no use of abbreviations, which on the other hand appear once in W1 and more distinctly in CH-SGs 383, a thirteenth-century tropary from present-day Switzerland.Footnote 46

Lux illuxit gratiosa offers more material for comparison, as E-Mn 6528 transmits its whole three-stanza poem: some of the variants are worth consideration:

In F, the inversion of the words hac and in in the first stanza (third line) is unique, but may well be ascribed to mere scribal distraction and it does not affect the prosody or the text underlay. W1 has the single reading auravit instead of iuravit (third stanza, first line), which is definitely a mistake. This inaccuracy, however, may have originated in a lack of coordination between scribe and decorator: as a matter of fact, the letter a is drawn as a blue minor initial, marking the beginning of a new stanza, and is the result of a stage in the process of manuscript compilation that is distinct from the writing of the main text in black ink.

Similarly, Ma presents the unique reading penitebit (third stanza, second line) in place of penituit adopted in all other sources. Theoretically, this cannot be considered a mistake, as the meaning of the sentence remains unaltered, except for the verb tense that switches from perfect to future in Ma.Footnote 47 The reason for the different tense lies in the origin of the passage itself, which is a quotation of Psalm 109:4: ‘Iuravit Dominus, et non pœnitebit eum’ (The Lord hath sworn, and will not repent). Ma seems thus to follow the biblical passage more closely; such a variant may have been found in the model used by the scribe of Ma or could even be due to the scribe’s inclination to adapt the passage to the sacred text.

Discrepancies between E-Mn 6528 and F involve the words Iuravit and David: the Madrid fragment presents David in all instances (second stanza, third line, and third stanza, first and fourth lines), which is the correct reading, but at the same time has the erroneous Iuravid in place of Iuravit. F consistently and incorrectly reads davit in place of David, but has the correct reading Iuravit, except for an unnecessary repetition of the syllable ra.Footnote 48 These discrepancies may suggest that there is a certain degree of separation between the textual traditions of Lux illuxit gratiosa in E-Mn 6528 and F; indeed, they may have originated in the alliterative feature of the passage that perhaps led scribes to confusion. There is even a chance the passage was already corrupt in their supposedly common exemplar, and that different attempts to correct the same error led to different results and different readings.

Consistent with the codicological evidence, the comparison of textual variants seems to indicate that, despite their similarities, E-Mn 6528 and F were not copied from one another but have a collateral relationship to a single model source. The analyses of musical variants of Legem dedit olim Deus and Lux illuxit gratiosa point to the same conclusion.

The comparison of Legem dedit olim Deus transmitted in E-Mn 6528 with the versions copied in the other sources points to variants in the musical text. Example 1 provides a transcription of the syllabic excerpt transmitted in all the sources.Footnote 49 A unison between duplum and tenor closes the word litterali (Example 1, at no. 4).Footnote 50 E-Mn 6528 is the only source with an e unison, whereas F and W1 conclude on f. Such a discrepancy may be attributed to scribal inattention in placing the notes on the stave. For example, the interval of a minor second displayed by the Sankt Gallen manuscript (Example 1, at no. 4) is certainly erroneous and suggests that such differences may not depend on separate traditions but rather on copyists’ distractions. With a few exceptions consisting mostly of minor notational differences (e.g. duplum, at no. 13; tenor, at no. 14; and duplum, at no. 16), E-Mn 6528 and F generally tend to share the same variants. W1 and CH-SGs 383 do not differ much either, but both have a unique distinct variant: the former is the only source with a g–g–a ascending figure in duplum, at no. 3, while the latter has a unique and more elaborate ligature pattern at no. 10.

Example 1 Legem dedit olim Deus, stanza 4, lines 1–4

Some slightly sharper differences are noticeable in the concluding cauda of Legem dedit olim Deus. Example 2 provides transcriptions of the second ordo of the cauda in the four sources. There are essentially no differences between E-Mn 6528, F and W1, with one exception: in the tenor, ternary long 3, W1 has a simple binary ligature in place of the binaria plicata displayed by both E-Mn 6528 and F. This means that in W1 we have an uninterrupted first mode ordo, while the other two sources have a shortened f as a resulting effect of the plica. CH-SGs 383, in addition to its total lack of the typical ligature patterns of the modal system, displays a completely different melodic reading of the passage.

Example 2 Legem dedit olim Deus, final cauda (second ordo)

The alignment of E-Mn 6528 and F, their contrast with W1, and the unmeasured notation of CH-SGs 383 are more apparent in Example 3, which includes the final four ordines and the conclusive punctus organi of Legem dedit olim Deus. At ternary longs 4 and 12, W1 lacks the plicae which are instead present in both E-Mn 6528 and F, determining a shortening of their preceding notes and a different harmonic and melodic conclusion of the ordines. W1 also provides a unique rhythmic arrangement of the final ordo: while E-Mn 6528 and F have a rather straightforward first-mode pattern, interrupted only by a plica at ternary long 15, W1 diverges from this configuration introducing a four-note ligature with currentes (duplum, ternary longs 16–17) and two single notes (tenor, ternary longs 16–17) that determine the extensio modi of the passage. The punctus organi is a further element of disagreement: essentially, no source shares exactly the same reading with another, but while E-Mn 6528, F and CH-SGs 383 display only some slight differences between each other, namely in the melodic ascent from f/g to c′ that introduces the cascade of currentes and the note(s) preceding the concluding unison d, W1 has a unique and more elaborate pattern – consisting of a sequence of a ternaria, a quaternaria and a binaria – that precedes the distinctive descending melodic seventh of the punctus organi.

Example 3 Legem dedit olim Deus, final cauda and punctus organi

As for CH-SGs 383, its melody follows the reading of E-Mn 6528, F and W1, with the exception of the five-note ligature in the duplum at no. 12 that ascends to a before descending to d as the other sources do. Its notation, however, marks a neat distinction between this manuscript and the other sources. CH-SGs 383 tends to lack plicae that are present in the other manuscripts (e.g. nos. 3 and 9) and conversely adds them where they are not (e.g. nos. 4, 7 and 10), but most notably, it displays unique non-mensural ligature patterns that do not allow rhythmic interpretation.

The fragment of Legem dedit olim Deus transmitted in E-Mn 6528 allowed limited comparison with the complete extant sources of the conductus. Nevertheless, it can be summarised that, whereas a few readings are certainly unique to individual manuscripts, E-Mn 6528 and F have more in common with each other than with the remaining sources. In particular, it seems that W1 systematically avoids the use of the plica within a first-mode context, thus resulting in a typical first-mode long-short pattern, whereas both E-Mn 6528 and F apply the plica to the same ligatures, providing a slight deviation from the rhythmic repetition (as in Example 2, tenor) or creating longer ordines, where the vertical tractus after the binaria plicata functions as a mark of alignment rather than a rest (as in Example 3). It thus seems that the scribes of these two sources were following the same notational tradition.

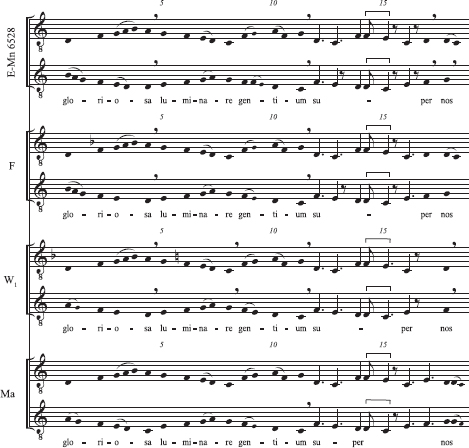

Further evidence comes from the longer fragment of Lux illuxit gratiosa transmitted in E-Mn 6528. The transmission of the opening cauda of this conductus is instructive. As evident from Example 4, E-Mn 6528 and F are identical, except for the missing specification of a b{fl} in the first ordo in the Madrid fragment.Footnote 51 In the duplum (ternary longs 1–7), both sources have the first ordo arranged in a typical third-mode pattern, consisting of a single note followed by three ternary ligatures and a rest. The upper voices in W1 and Ma share a different ligature arrangement of the ordo, which displays an isolated note followed by a ternary and binary ligature in succession: this passage can be transcribed as first mode with extensio modi. The comparison of the tenor parts reveals the same differences: F and E-Mn 6528 both have, after four ternary longs, a binary and ternary ligature; W1 and Ma instead invert the order of these ligatures, suggesting a different arrangement of short and long durations.

Example 4 Lux illuxit gratiosa, opening cauda

Similarly, the comparison of the second ordo in the four sources confirms the alignment of F and E-Mn 6528 on the one hand and W1 and Ma on the other: in particular, the dissimilar ligature patterns in the tenor (1, 1, 1, 2, 3, 1 in F and E-Mn 6528; 1, 1, 3, 3, 1 in W1 and Ma) determine different rhythmic arrangements, which in turn bring different rhythmic interpretations of the duplum parts, which otherwise display rather similar configurations in all manuscripts.

The first syllabic section of Lux illuxit gratiosa (Example 5) also displays some minor variants that highlight the association of E-Mn 6528 and F in opposition to W1 and Ma. For instance, the syllable glo in the tenor part (at no. 1) in both E-Mn 6528 and F has a ternary ligature with currentes (essentially a climacus), while the other two sources have a two-note ligature. Also, it is possible to notice how the syllable gen in the duplum (at no. 9) is sung on a note with an additional ascending plica in both E-Mn 6528 and F, while the other two manuscripts have a simple binary ligature and no plica. Likewise, the short rhythmic passage (ternary longs 12–16) at the end of Example 5 reveals some differences that are indicative of the consistency between E-Mn 6528 and F: both manuscripts make the identical use of rests in this section, whereas W1 and Ma lack almost all the rests and also tend to slightly disagree here (Ma has even a unique placement of the word super, resulting in the passage being sung almost entirely on the syllable per rather than su).

Example 5 Lux illuxit gratiosa, stanza 1, lines 3–5

The cauda that concludes the first stanza of Lux illuxit gratiosa (see Example 6) confirms again the close correspondence between E-Mn 6528 and F as opposed to the alignment of Ma and W1. Within this sine littera passage, the Madrid fragment and F agree essentially in all aspects, except in the very final part (ternary longs 30–3), where the reiteration of a pitch and a different ligature pattern in F lead to a slightly different rhythmic arrangement. W1 displays essentially the same version, with some minor variants in the duplum (ternary longs 6–7 and 14–15) and a different rhythmic pattern in both parts towards the end of the melisma (ternary longs 27–33), determined by a different grouping of ligatures, lack of rests and repetition of pitches. Contrary to expectations, Ma does not align with W1, but neither does it with E-Mn 6528 or F: instead, it displays a unique and sharply distinct rhythm characterised by ternary longs, mostly repeating the same pitch, and sparser ligatures. The result is a longer, slower cauda that shares the same melody with the other three sources but deviates from these sources in terms of rhythm.

Example 6 Lux illuxit gratiosa, stanza 1, line 5 (cauda)

There are a number of possible explanations for why Ma, which so far seemed to align with W1, takes its own path in this passage. The divergence may be attributed, for instance, to the scribe of Ma, who might deliberately have modified a passage given in his exemplar. But it may well be that the longer version of the cauda was already present there. In the absence of the models used by scribes in putting together their collections, coupled with the fact that we cannot precisely determine how the process of compiling a book of polyphony took place, both explanations are equally plausible. Despite the fact that Ma presents this unique variant, its version of Lux illuxit gratiosa, as seen in previous comparisons, nevertheless pairs with the one provided in W1 rather than that given in E-Mn 6528 and F. This is further confirmed by additional passages of the conductus.

Example 7 presents the ending of the cauda that opens the third stanza of Lux illuxit gratiosa. Again, E-Mn 6528 and F share the same ligature patterns in both parts (1, 2, 3, etc.). These patterns are essentially inverted in W1 and Ma (1, 3, 2, etc.), resulting in a different arrangement of short and long values. Another noticeable variant appears in the tenor, at no. 7 on the syllable ra: E-Mn 6528 and F have a repeated a with an ascending plica added, whereas both W1 and Ma have a four-note ligature with no repeated note and no plica.

Example 7 Lux illuxit gratiosa, stanza 3, line 1 (opening cauda)

An additional variant that further separates E-Mn 6528 and F from W1 and Ma can be noticed in Example 8. The beginning of the cauda that concludes the conductus on the syllable su is notated in the duplum (ternary longs 8–11) with the same pattern of two longs followed by a ternary ligature in E-Mn 6528 and F, even though F adds a rest between the second longa and the ternaria. W1 and Ma instead present a common pattern made of a long, a ternary ligature and another long (which in W1 is followed by a rest that is not provided in Ma). This passage is not identical in any of the sources, but still the rhythmic solutions adopted support once more the association of E-Mn 6528 and F – in opposition to the variant shared by W1 and Ma – that we have observed so far. Other variations can be noticed in the cum littera section preceding the cauda: at the duplum at nos. 3 and 4, for instance, there is a slight inconsistency among all sources with the exception of E-Mn 6528 and Ma, which share the same reading (it is mostly a matter of the lack or presence of plicas, even though the descending melodic excerpt from c′ to g is maintained in all manuscripts). More consistent is the unique variant in W1 in the tenor at no. 6, which organises its descending pattern from f to c with a combination of a ternary and a binary ligature, whereas all other sources have a simpler climacus.

Example 8 Lux illuxit gratiosa, stanza 3, line 4

Despite the few discrepancies identified, it seems clear that the musical tradition presented in E-Mn 6528 is closely related to that provided by F. W1 and Ma appear to follow and share a distinct tradition, while CH-SGs 383 seems to follow its own non-modal interpretation of Legem dedit olim Deus that includes a few unique melodic variants that can either be due to the scribe’s intervention or a different tradition of the conductus. This is unsurprising, since this tropary is fairly different in appearance and content from the other sources.

One of the most notable aspects of the comparison given above is that the ligature patterns displayed by E-Mn 6528 tend to be the same as those used in F, in opposition to the solutions adopted in W1 and Ma. In particular, E-Mn 6528 and F use ligature patterns that gesture towards third-mode rhythms, whereas the same passages in W1 and Ma are notated in the first mode (see Examples 4 and 7 above). This specific divergence may be seen as indicative of the reading in W1 and Ma being earlier, and possibly closer to a lost archetype,Footnote 52 than that provided in E-Mn 6528 and F: both Ernest Sanders and Edward Roesner suggested that the main pre-modal rhythmic principle of early Parisian polyphony was a long–short pattern that was later classified by theorists as first mode.Footnote 53 It might thus be possible that, to some extent, the notational (and therefore rhythmic) choices adopted by E-Mn 6528 and F represent a later revision and update of the older version given in W1 and Ma, whose modal notations are still somehow connected to the pre-modal predominance of the long–short–long pattern. It would not, however, be wise to mark the reading of W1 and Ma as ‘original’, as it is not possible to determine the exact span of time that separates the creation of a conductus from the moment it was written down into a manuscript collection.Footnote 54 Moreover, the idea of an original form of the repertory implies a certain stability of the repertory itself, and such stability is yet to be demonstrated or discarded. Be that as it may, the notational correspondences between E-Mn 6528 and F are indicative of a shared musical house-style.

FROM A PARISIAN WORKSHOP TO AN IBERIAN BOOKBINDER

When the considerations of the musical congruence of the Madrid fragment with F are combined with the codicological and palaeographical denominators common to the two sources, it is reasonable to conclude that they are closely connected. Rather than a lineal relationship, where one manuscript is copied from the other, the evidence discussed above suggests that the two sources are collaterally related and derive from a common musical and codicological model. This model must have been held in a Parisian workshop and functioned as the benchmark for the production of polyphonic books with almost identical characteristics.Footnote 55 The rather minor inconsistencies between F and E-Mn 6528 hardly contradict the notion that the two manuscripts were compiled from the same exemplar. These inconsistencies could simply be explained by assuming that the transmission of polyphony was rarely a purely mechanical process, and that experienced scribes often acted as ‘editors’. Catherine Bradley has recently drawn attention to the possibility that the scribe of F may have been directly responsible for the reworking of some motets and conductus-motets.Footnote 56 Yet the discrepancies found in the conductus of E-Mn 6528 and F are so trivial that they cannot be characterised as the result of a reworking process. Rather, they might be the result of a flexible approach to the process of copying, in which the scribe felt free to contribute with his own experience and view of performance practice.Footnote 57

What is striking here is the apparently well-structured chain production of books around the mid-thirteenth century. The process involved scribes and artists from different shops.Footnote 58 F, for instance, was furnished with text and music by a scribe and a notator, then sent to an artist who drew filigree minor initials, and finally to a painter working in the Johannes Grush atelier.Footnote 59 One wonders whether E-Mn 6528 may have followed the same itinerary. It is also reasonably apparent that E-Mn 6528 and F, as well as LoA, were all produced over a relatively brief chronological span, sometime between 1245 and 1255.Footnote 60

The hypothesis that F, LoA and E-Mn 6528 represent evidence of the multiple production of books of polyphony, which were issued by the same workshop with identical formats, shared contents and clearly recognisable house-style features, brings to mind the pecia system adopted for university texts. A pecia is a separate portion of a complete work that university stationers would rent to students, masters and scribes, thus facilitating the process of multiple, simultaneous copying of the same book.Footnote 61 This system started to be regulated by the University of Paris only between the third and the last quarter of the thirteenth century,Footnote 62 roughly one generation after the production of F, LoA and E-Mn 6528. However, the system was already in place in Paris decades before the university and the city stationers standardised it. The Paris Dominicans of the rue St-Jacques, for instance, applied their own form of chain reproduction by copying from unbound quires, called pecias, before 1250.Footnote 63 Manuscripts copied from pecia were therefore not necessarily associated with university teaching.Footnote 64 Workshops produced books in pieces (gatherings and fascicles) without adopting the pecia system strictu sensu.Footnote 65 Lay bookmakers soon saw the prospective economic advantages of chain production as devised by the Dominicans, and started to adapt the system to their purposes.Footnote 66

The reconstruction of the exemplars of LoA and E-Mn 6528 is a matter nearly left to speculation. The very likely prospect that F was put together by copying from distinct exemplars,Footnote 67 however, matches the standardised book-making practices in thirteenth-century Paris. In his description of thirteenth-century Parisian books of polyphony, Anonymous IV, writing in the late thirteenth century about events he may have witnessed several decades earlier, gives details of different and separate manuscript entities (volumina)Footnote 68 which bear close similarities to the identifiable subsections of F, their coherence being determined essentially by the number of voices and musical genre. Mark Everist has recently proposed that Anonymous IV based his description of two-part conductus volumina on his – at times hazy – memory of what might have been the exemplars of F.Footnote 69

One can thus imagine a Parisian workshop holding Anonymous IV’s volumina, each transmitting pieces with certain characteristics. Multiple scribes would be given one volumen each and could even work simultaneously. Yet whereas scribes operating in the same workshop would use these volumina to copy music on parchment prepared with identical mise-en-page, their attitude towards the repertory, as well as conditions of compilation and fascicular construction, might vary. The compiler of F was determined – or requested – to include as much material and in the most complete form as possible, while that of LoA had a more idiosyncratic approach to the repertory transmitted in the exemplars and made a selection of pieces (four organa, three motets and five conducti), some of which he did not bother to copy in their full versions.Footnote 70

These different approaches to the corpus of polyphony, and perhaps the variable circumstances of fascicular production, are clearly mirrored by the different standards of decoration, very high in F and the rather modest in LoA, and suggest the workshop’s ability to adjust its work to satisfy different standards of commission and their budgets. The two-part conductus fascicles of E-Mn 6528 and F were possibly copied from the same booklet (or volumen).

Given the shared features of E-Mn 6528 and F, it seems reasonable to assume that the manuscript from which the fragment originated held a status comparable to that of F. Since a royal context for F seems plausible, one wonders whether the Ars antiqua fragment of E-Mn 6528 was the product of an equally high-ranking commission. In 1987 Rebecca Baltzer identified seventeen lost Notre-Dame manuscripts in catalogues of medieval libraries of Europe.Footnote 71 Judging from the very brief descriptions given in these catalogues, most of these manuscripts seem to have shared (to what extent is obviously impossible to determine) the same contents and organisation of F, beginning with four-part organa (notably, the gradual Viderunt omnes) and ending with monophonic pieces. Unsurprisingly, these books once belonged to personalities and institutions such as Pope Boniface VIII, King Edward I of England, the Sorbonne in Paris, and St Paul’s Cathedral in London.Footnote 72

Thus far there is no demonstrable evidence that the same workshop where F, LoA and E-Mn 6528 were possibly compiled produced many other similar manuscripts. However, it is entirely plausible that a Parisian workshop producing volumes of Ars antiqua polyphony was a successful business; its co-ordinators took care to acquire fine-quality parchment and hire professional scribes, notators specialised in polyphonic music,Footnote 73 skilled pen-flourishers and – at least in the case of F, which was a royal commission – talented illuminators.Footnote 74

We do not know who commissioned the manuscript from which the Ars antiqua fragment in E-Mn 6528 was copied, nor can we determine when, how and why the unbound gathering(s) arrived in the Iberian Peninsula. Yet we can imagine a number of possible scenarios. The only fact we can assume with a high degree of certainty is that the parchment was available to a mudéjar bookbinder in fifteenth-century Spain. Physical evidence suggests that the fragment had not been used as recycled material prior to its insertion into the binding of E-Mn 6528. It seems rather unlikely that waste material travelled more than 600 miles for the mere purpose of being recycled.Footnote 75 It is thus reasonable to assume that the Ars antiqua manuscript arrived in the Iberian Peninsula in the thirteenth century, when it was still regarded as a valuable manuscript.

Castilians had been active at the French court in Paris ever since 1200, the year in which Blanche of Castile went there as the future wife of Louis VIII, becoming mother of Louis IX, with emissaries from her sister Queen Berenguela – whose official residence was the royal palace in Las Huelgas of Burgos. The two sisters Blanche and Berenguela, each a dominant figure in affairs of state,Footnote 76 served as dynamic poles for the transmission of cultural currents.Footnote 77 This connection explains, for example, the presence of ‘political’ monophonic conducti with texts by Philippe the Chancellor in the Las Huelgas codex.Footnote 78 Many other notable figures of the Castilian political and ecclesiastical scene were present in Paris during the first half of the thirteenth century. Rodrigo Ximénez de Rada – intellectual, historian, royal chancellor and influential archbishop of Toledo between 1209 and 1247 – studied in Paris and later returned there as a diplomat and royal chancellor. Archbishop Ximénez, who most likely met Philippe the Chancellor and Perotinus in Paris, must have played a crucial role in the introduction of French polyphony to the Cathedral of Toledo.Footnote 79 In the 1240s, two sons of the king of Castile were also sent to study in Paris: Infante Felipe and Infante Sancho, future archbishops of Seville and Toledo respectively. By 1248, the Castilian prospect at the very summit of French royalty continued to be highly promising. In April of that year, the new archbishop of Toledo Juan de Medina was invited to officiate at the consecration of the Sainte-Chapelle as the only foreign prelate present at that solemn and highly charged occasion. One month later, Louis IX offered him various gifts, including a fragment of the True Cross and other relics, which made their way to Toledo.Footnote 80 Masters of polyphony (organistae) are documented in Toledo Cathedral since the twelfth and throughout the thirteenth century; Archbishop Juan de Medina might therefore have been interested in acquiring a new manuscript of Parisian polyphony. The cathedrals of Burgos and León were also deeply influenced by Parisian art and culture, and there is evidence that their bishops and cantors were particularly interested in polyphony.Footnote 81

Any member of the Castilian royal family and high clergy (bishops, archbishops, infantes) with direct contacts in Paris could have acted as potential commissioners of a beautiful Parisian manuscript of polyphonic music. The royal connection, however, deserves further exploration. In the 1250s, Alfonso X began to plan an extremely ambitious strategy aimed at pushing his own candidacy for the Holy Roman Imperial crown. Alfonso’s plan included the union of the kingdoms of France and Castile. In 1255, the kings of France and Castile agreed to betrothe their respective heirs – the first-born son of Louis IX and Alfonso’s eldest daughter, Berenguela, at the time the heir to the Castilian throne.Footnote 82 In June of that same year, Alfonso’s chancellor took part in an espousal ceremony in Paris on behalf of the bride. The dynastic project failed because the French heir died prematurely and a boy was born to Alfonso. In any case, negotiations and contacts between the two courts during the early 1250s must have implied an intense cultural exchange, in which ceremonies and gifts played an essential role.

In the 1260s, a new Franco-Castilian project began to take shape. In 1266, Alfonso sent his emissaries from Seville to Paris to negotiate the marriage of his new heir, Alfonso de la Cerda, to the daughter of Louis IX, Blanche of France. The Franco-Castilian wedding finally took place in Burgos in 1269 with the greatest solemnity.Footnote 83 The extravagant ceremony was split between the Royal Abbey of Las Huelgas and the cathedral. Francisco Hernández argues that it was most likely on this occasion that Alfonso X received the three lavishly illuminated volumes of the Bible moralisée – the so-called ‘Bible of St Louis’ now preserved in the Cathedral Library of Toledo – as a gift from Louis IX.Footnote 84 This extremely fine product of Parisian craftsmanship dates back to Blanche of Castile’s first regency and may actually have been commissioned by Blanche herself for her young son Louis IX.Footnote 85 The three volumes, mentioned in Alfonso X’s last will,Footnote 86 ended up in the treasury of the Cathedral of Toledo sometime after Alfonso’s death in 1284. In the same last will, Alfonso X mentioned at least one other book in four volumes from Louis IX.Footnote 87 One could speculate whether the French king also sent a book of Parisian polyphony to his daughter’s father-in-law, a very fitting gift for a music lover like Alfonso X the Wise.Footnote 88 This would be in agreement with the highly regarded status of a manuscript like F.Footnote 89 Another possibility left to speculation is whether the Ars antiqua manuscript from which the Madrid fragment was torn belonged to the private chapel of Louis IX’s daughter, Blanche of France, whose possessions passed through different hands after her hasty flight from Castile in 1278.Footnote 90

Be that as it may, the Ars antiqua fragment E-Mn 6528 sheds new light on the context of the production the largest, principal extant source of Notre-Dame polyphony, F. The sources of thirteenth-century polyphony that have survived practically untouched by the merciless vicissitudes of time have done so because of ‘historical caprice’, to borrow Craig Wright’s words.Footnote 91 As a matter of fact, whereas F remained nearly undamaged in the hands of the Medici family, even escaping the iconoclastic fury of Giacomo Savonarola and his followers in the late fifteenth century,Footnote 92 its ‘sister’ codex, now witnessed by the fragments in E-Mn 6528, was dispersed, leaving only a small trace of its existence.