In a 1997 article on the early Tudor court and the Eton Choirbook (Eton College Library, MS 178), Magnus Williamson posed an important question: ‘was [the Choirbook] the product of a provincial or a metropolitan environment?’ To answer this query, Williamson traced links between Eton College and other educational institutions, showing connections to Arundel College, Fotheringhay College and Windsor Chapel, while focusing on the college’s stronger ties to Oxford and Cambridge. As Williamson has shown, personnel moved regularly back and forth from Eton to Oxford, and a direct relationship between Eton and King’s College, Cambridge facilitated the transmission of singers as well as musical works. By documenting specific instances of personnel and music travelling between these educational institutions, Williamson sketched out likely routes that facilitated the spread of polyphonic repertory and singers to Eton in late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century England.Footnote 1 Similar paths are certainly easy to trace in later periods, where a wealth of documentary evidence containing names, dates and payments to musicians is more readily available.Footnote 2 Yet the significance of the links Williamson uncovered is worthy of further exploration – while his essay demonstrates that these provincial centres played a critical role in the transmission of late medieval English polyphony, I argue that this evidence sheds light on the presence of a network of educational institutions, located primarily in the south-east of England, which linked individuals and repertory to one another and was directly responsible for nurturing specifically English ideas about music and practices of musical style.

Numerous scholars of sixteenth-century English music have documented evidence of links between institutions, patrons and musical style in the early Tudor period, of course. Roger Bowers’s research on medieval English institutions ranging from monastic and secular collegiate churches to aristocratic, ecclesiastical and royal chapels has laid much of the necessary groundwork for undertaking further study of these institutions; without his detailed analysis of the inner workings of individual foundations, comparative study would be impossible.Footnote 3 On a more local level, Fiona Kisby has demonstrated strong ties between several Gentlemen of the Chapel Royal and the institutions of early Tudor Westminster, specifically its parish church of St Margaret’s, and the royal college of St Stephen.Footnote 4 Richard Lloyd and Hugh Ballie have uncovered similar links between musicians working in London’s parishes, while Clive Burgess and Andrew Wathey’s study of church music in English towns offers evidence of individuals travelling from their home institutions to other towns, cities and cathedrals to copy (or bring with them) existing polyphony.Footnote 5 Theodor Dumitrescu has tackled the question of musical networks in England at this time from a different angle, considering instead interactions between the early Tudor court and Continental institutions and individuals, and questioning the long-accepted notion that English musical style and practice were truly insular during the early sixteenth century.Footnote 6 It would not be a stretch to suggest, then, that all of England’s regional and even local centres were, to a certain extent, connected with one another in a way that facilitated the transmission of musical knowledge and repertory.

The network that I propose to examine here, however, is one that joined specific colleges and universities within England. Although these educational institutions may of course have received materials from elsewhere, including the royal court and even abroad, the ties I wish to highlight are those forged between the scholarly hubs that were joined primarily by academic pursuits rather than patronage or commercial enterprise. Williamson’s discovery that most of the repertory in the Eton Choirbook hails from provincial sources raises a further question: how else were such institutional links forged, and what additional types of musical materials might have travelled across such a network? Whereas Williamson is concerned solely with the transmission of musical works, in this essay I consider the spread of musical thought between these institutions more broadly, examining late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century English polyphony of the Eton Choirbook through the lens of contemporary theoretical writings. Although the theoretical sources on English music at the turn of the century are relatively few, they too suggest connections to musical life at the institutions Williamson has studied.Footnote 7 I concentrate here on the writings of John Tucke and John Dygon, two musicians educated at Oxford in the first decade of the sixteenth century whose works contain traces of the shared education they received. I will show how specific concepts elucidated in Tucke and Dygon’s writings echo some of the compositional solutions adopted in contemporaneous practice. In the light of Williamson’s work on the provenance of the Eton repertory, I argue that these manuscripts provide further evidence for a well-established network linking English educational institutions – with the triangle of Eton, Oxford and Cambridge at its centre – which allowed for the transmission of musical ideas throughout the south-east and perhaps beyond.

In taking as my focus the institutions of Eton, Oxford and Cambridge, I do not mean to imply that it was only these centres which display close musical relationships to one another; certainly the repertory in the Eton Choirbook alone, which hails from Arundel, London, Lincoln, Worcester and Windsor as well as Oxford and Cambridge, suggests the existence of a larger network of musicians and patronage across England. The presence of some compositional similarities between the Eton Choirbook and the roughly contemporary York Masses, moreover, indicates that the spread of musical knowledge in England was geographically broad (assuming, as both Lisa Colton and Theodor Dumitrescu have posited, that the York fragments were copied in or near York).Footnote 8 Instead, I make the case that these institutions were at the centre of an educational network from which more complex compositional techniques were disseminated to other institutions, whether via the transmission of music-theoretical writings or through the spread of polyphonic repertory. As Roger Bray has shown, Oxford and Cambridge were unique among European universities in combining choral provision (in the form of college choirs) with the offering of degrees in music; moreover, the academic study of both musica speculativa and musica practica led to training in ‘practical’ composition that was often highly theoretical and complex.Footnote 9 The close relationship of these institutions to Eton College, with personnel moving regularly back and forth between Eton and either Oxford or Cambridge, suggests that similar practices, though admittedly on a smaller scale, may have taken place at Eton as well. The choirbook’s certain provenance, when compared to contemporary sources of polyphony such as the Ritson Manuscript (London, British Library, Add. MS 5665), allows such connections to be made with relative certainty.Footnote 10 In addition, Eton College’s educational function sets it apart from numerous other similar choral foundations, such as those at Christ Church, Canterbury or St Stephen’s Westminster. Indeed, the differences in the level and type of education offered at Eton, Oxford and Cambridge made this nexus amenable to the musical transmission which took place between these central establishments. Although there is much work still to be done on the relationships between various musical centres in early sixteenth-century England, in what follows I suggest that a re-examination of these musical and theoretical sources, and the academic contexts which produced them, may provide stronger evidence for such connections between individuals, institutions and musical style in the early Tudor period.

JOHN TUCKE, JOHN DYGON AND EARLY SIXTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH THEORY

Written over the course of several decades, John Tucke’s notebook (London, British Library, Add. MS 10336) encompasses a wide range of primarily musical subjects, incorporating both pre-existing and original material. Probably begun during his last year as a scholar at Winchester College in 1500, the notebook probably reflects the training he received as an undergraduate at Oxford in both formal and informal instruction. Indeed, it contains both theoretical texts as well as material that might have been important for a practising musician whose position required teaching choirboys over the course of his career.Footnote 11 In addition to a discussion of the rhythmic modes and an abbreviated version of the Libellus cantus mensurabilis attributed to Johannes de Muris, which might have been standard topics in the Oxford curriculum, Tucke also drew on earlier English music theory.Footnote 12 In his edited translation of several sections of the manuscript, Ronald Woodley has shown how Tucke assembled these parts over a lifetime: the explicitly borrowed material, for example, dates from his Oxford days; while Tucke mostly copied the material himself, he also incorporated pages in a different hand.Footnote 13 As the book was most likely not bound until the 1520s, it is somewhat difficult to reconstruct the exact order in which Tucke himself received or copied information.Footnote 14

These two manuscripts by Tucke and Dygon share a common concentration on proportion, both musical and otherwise, although their contents are otherwise radically different.Footnote 15 Proportional relationships, of course, were a serious consideration in both English and Continental music theory at the turn of the sixteenth century, and the English interest in proportion dates back further than the writings of these two sixteenth-century scholars.Footnote 16 Of the miscellaneous notes dedicated to musical topics in London, British Library, Lansdowne MS 763, a manuscript copied c. 1450–60 in England, several deal with proportions and their classification.Footnote 17 The most theoretically rigorous of these is a short treatise in English by Chilston, one of three vernacular treatises in the volume.Footnote 18 Beginning with a discussion of the most basic proportional relationships often found in contemporary polyphony, this text also features a table of ratios that includes proportions of much higher numbers than would be necessary in music, ending with the ratio 78:42.Footnote 19 Its inclusion in the manuscript alongside other writings on the proportions in Latin certainly highlights an English preoccupation with proportion – one which would continue to influence later writers and composers. Chilston’s treatise, moreover, is not the only such English tract on musical proportions from this period; as Theodor Dumitrescu has demonstrated, many of these writings derive from a common source, indicating a widespread and uncontested understanding of basic proportions in theory and practice among English musicians at this time.Footnote 20

In addition to texts on proportion that deal more directly with its application to written polyphony, Tucke incorporated writings on number theory and arithmetic and geometric proportions.Footnote 21 Furthermore, he copied an additional treatise on proportion by one of Europe’s leading theoretical authorities: the Proportiones secundum ioannem ottoby, the only treatise by John Hothby to be found solely in English sources.Footnote 22 In addition to preserving these earlier texts, Tucke’s notes concern the relationship between mathematical proportions and mensuration changes. Five excerpts, for example, deal with the use of colouration to show proportional relationships – including not only how to use void and full versions of the common black and red notation, but also additional colouration. In one of two passages discussing extensive colouration, Tucke indicates how multiple colours might be used:

The colours requisite to musical proportions are these: black, green, blue, red, yellow. The colours in their correct order are these: black, green, yellow, blue, red, sanguine, purple. Green to black and red to blue is sesquioctava proportion [9:8]. Likewise, blue to black and yellow to blue is sesquitertia proportion [4:3]. Likewise, red to black is sesquialtera [3:2]. Likewise, red to green sesquitertia [4:3]. Likewise, red to blue sesquioctava [9:8].Footnote 23

In various combinations, then, these colours would allow for the expression of a number of different relationships. In another excerpt Tucke also points out that colouration can be employed with mensuration signs to produce ‘remarkable operations’ [mirabiliter operari], although he does not define the complex relationships that might result from such combination.Footnote 24

In addition to this treatment of colouration, Tucke lists a number of proportional relationships between the mensuration signs themselves. By far the most common of these is sesquialtera [3:2], which Tucke claims can be notated in five different ways: ![]() E to

E to ![]() C,

C, ![]() D to

D to ![]() A,

A, ![]() J to

J to ![]() D,

D, ![]() C to

C to ![]() F, and

F, and ![]() L to

L to ![]() A.Footnote

25

Tucke’s focus on sesquialtera suggests a link to contemporary practice; although a number of these signs do not appear regularly in practical sources, sesquialtera was by far the most common ratio employed by composers whose works appear in the Eton Choirbook.

A.Footnote

25

Tucke’s focus on sesquialtera suggests a link to contemporary practice; although a number of these signs do not appear regularly in practical sources, sesquialtera was by far the most common ratio employed by composers whose works appear in the Eton Choirbook.

John Dygon, Tucke’s slightly younger contemporary, was also educated at Oxford in the first decade of the sixteenth century, later serving as prior of St Augustine’s monastery in Canterbury at the time of the Dissolution.Footnote 26 Manuscript O.3.38 of Trinity College, Cambridge contains two separate but related texts on arithmetical proportions and their use in polyphonic music. To call Dygon the author of the two treatises in the manuscript that bears his name is perhaps misleading – the first is largely extracted and paraphrased from Book IV of the Practica musice of Gaffurius first printed in Milan in 1496, and the second treatise, more original in its contents, nonetheless also suggests Gaffurius as a model.Footnote 27 Although the second lacks introductory material and a title, in his edition of the manuscript Theodor Dumitrescu has demonstrated that the two ought to be read as separate treatises. Both texts are entirely concerned with proportions and mensuration, and the second mirrors the first in its layout and content, indicating that it was intended to supplement the first.Footnote 28 Dumitrescu has carefully documented the differences between Gaffurius’s original text and Dygon’s adaptation, beginning with Dygon’s omission of Gaffurius’s introduction.Footnote 29 One notable addition, for example, is Dygon’s discussion of inductiones proportionum, a practice wherein a composer uses one common proportion to lead into another – say, writing a breve’s length of sesquialtera to introduce sextupla – for ease of performance. As Dumitrescu notes, this practice appears to have been specifically English, given its mention in another famous sixteenth-century English theoretical treatise: Thomas Morley’s A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke (1596).Footnote 30 Indeed, for Richard Pace, an English humanist writing in 1517, this practice was a matter of national importance: ‘Still, I dare say that our English musicians have invented those things called the inductions of proportions, with the greatest subtlety of talent . . . and in that one thing they have surpassed all Antiquity.’Footnote 31

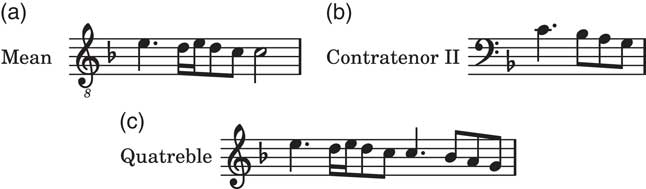

In addition, while Gaffurius’s proportions indicate a relationship between two sections in a single part, Dygon defines proportions in relation to the tenor. In examples which contain multiple proportional shifts, Dygon ‘resets’ the shifted part back to its original mensuration through the use of a mensuration sign and a return to black notation, a practice which Dumitrescu notes is standard in contemporary English repertory as well as in many Continental sources.Footnote 32 For example, in his first (and most basic) example of the proportion 2:1, Dygon sets a discantus line against a tenor, in which two minims in the discantus equal one minim in the tenor (see Example 1a and b). The subsequent 4:2 proportion with respect to the semibreve provided in the same example follows a brief return to the original mensuration in the discantus.

Example 1 John Dygon, 2:1: (a) original notation; (b) modern notation

Dygon’s most prominent change to Gaffurius’s text is his replacement of the original examples with newly composed music in a style comparable to contemporary English polyphony, as in Example 1.Footnote 33 A further addition to Gaffurius’s original is a substantial body of newly composed three-part examples, in which two upper parts are given in different proportional relationships with the tenor.Footnote 34 As seen in Example 2, this type of model allows for a complexity of proportional relationships that is not possible in two-voice examples.Footnote 35 The top discantus line is in a 3:1 relationship with the tenor, and the relationship between the lower discantus part and the tenor is 5:1. This layering results in a 5:3 relationship between the two discantus parts. Such complexity also recalls Tucke’s excitement about the proportional possibilities created through the combination of colouration and mensuration signs, although where Dygon provides practical examples, Tucke gave none. The intellectual rigour required to understand Dygon’s examples thus highlights the likelihood that the manuscript’s contents hail from Dygon’s university days.

Example 2 John Dygon, superbipartiens tertias: (a) original notation; (b) modern notation

Dygon’s second treatise, although modelled on the first, describes a system of combining mensuration signs to indicate specific proportions that is almost completely absent from practical sources.Footnote 36 It is similar, however, to the system of proportional relations between mensuration signs described in Tucke’s notebook. Dumitrescu argues that the correspondences between Dygon’s second treatise and this passage in Tucke’s notebook, which are too substantial to be coincidental, suggest a specifically English interest in this theoretical discussion. Furthermore, he hypothesises that this overlap stems from the music theoretical curriculum at Oxford, where both men were educated.Footnote 37 Although this system itself was entirely theoretical, and is therefore not directly applicable to contemporary repertory, it points to an intellectual engagement with proportions that may have been shared, through writings like these, with colleagues at other institutions. In addition, the focus on sesquialtera in both treatises, although not explicitly defined by either author but nevertheless clear in their extensive use of this ratio, links these writings on proportion to contemporary English polyphony.

musical style in the eton choirbook: an overview

The Eton Choirbook is one of three early Tudor choirbooks; compiled primarily between c. 1500 and 1504 for use in the chapel at Eton College, it originally contained sixty-seven Latin antiphons and twenty-four settings of the Magnificat, as well as an extended setting of the St Matthew Passion and a thirteen-part canon. The composers whose works are included belonged to a wide range of major choral institutions in England, among them King’s College, Cambridge; Magdalen College, Oxford; Arundel College; Worcester Cathedral; Wells Cathedral; Lincoln Cathedral; Winchester College; and the royal chapel at Windsor, St George’s.Footnote 38 As Dumitrescu notes in the preface to his edition of the York masses, the Eton repertory offers but one piece of evidence for the wide variety of musical styles in vogue in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries in England; none of the extant sources can be taken as representative of a single, distinctive ‘English’ style.Footnote 39 Nevertheless, the inclusion of works by composers associated with a number of prestigious English institutions indicates at the very least that the Eton Choirbook provides a sample of music that was performed at wealthy regional and educational centres across England, at least for celebratory feasts and Salve services. The complex connections between these establishments, of course, can be difficult to trace. As Williamson has demonstrated, moreover, the origination of the repertory at one particular institution does not mean it was transmitted directly to another; instead, such music might go first through an intermediary centre and then back out to another regional location. Indeed, such was most likely the case for the music in Eton originating in the royal household chapel, which Williamson posits reached Eton through King’s College, Cambridge, rather than arriving directly from Windsor.Footnote 40 Williamson’s evidence thus further supports the idea that Cambridge, Oxford and Eton formed the centre of an English educational network through which musical works and ideas were transmitted.

There are a number of musical features that set the music of the Eton Choirbook apart from works being created by Continental composers for similarly important institutions at the same time, as several scholars have noted. In his landmark study Latin Church Music in England c. 1460–1575, Hugh Benham identified several of these traits in the Eton repertory, including dense textures, lines that generally avoid any of the text-painting present in contemporary Continental compositions, extensive melismatic writing, triadic harmonies, a complex rhythmic interplay between voices, and the wide compass of the voices.Footnote 41 Although these features are not unique to the Eton Choirbook, they play a prominent role in these compositions, and when taken collectively demonstrate how these works form some type of cohesive whole.

More detailed scholarship on the Eton Choirbook has illuminated and clarified several of these compositional features, further highlighting the importance of this repertory for understanding early Tudor polyphonic style. In her 1998 dissertation on late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century Marian polyphony in England, Noël Bisson advocated new methods of analysis for this repertory, quantifying some of the differences between English and Continental musical style during this period.Footnote 42 While Bisson has convincingly argued that there is no single ‘Eton style’, given the wide chronological and geographical makeup of the collection, she concedes that there are nevertheless several basic stylistic characteristics that differentiate this music from that found in Continental sources.Footnote 43 Although the works in the manuscript span roughly forty years – the oldest generation of composers was active in the 1460s and 1470s, and Wylkynson’s Salve regina was probably written between 1505 and 1515 – when compared to Franco-Flemish or Italian music from the same period the English emphases on extreme contrasts of vocal texture, rhythmic interplay and proportional writing are conspicuous. In addition, while some imitation occurs in the Eton repertory – and more in later works than in earlier ones – these composers were not interested in writing highly imitative counterpoint like their Continental counterparts, but rather in creating a dense web of sound with a constantly changing texture.Footnote 44 More recently, Fabrice Fitch has pointed to a pattern of sixth resolution which first emerges in English compositions with the Eton repertory, in which a sixth (either major or minor) is resolved downwards by step on a following minim, resembling an appoggiatura. As Fitch demonstrates, this treatment of the sixth is so widespread in Eton that it warrants the label of ‘Eton sixth’.Footnote 45

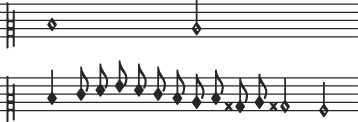

The lack in Eton of clear segmentation or organisation around the syntax and poetic structure of a chosen text so prevalent in Continental works has led many scholars, including Bisson, to argue that there is an improvisational quality to the writing.Footnote 46 Whereas earlier scholarship focused solely on the analysis of musical style through comparative study, Bisson suggests links between English theoretical writings and musical practice. Her work reintroduced an often-forgotten theoretical treatise by the so-called ‘Scottish Anonymous’ on a compositional technique called countering, described only in a single late sixteenth-century Scottish manuscript (British Library, Add. MS 4911).Footnote 47 A more complicated technique than either faburden or descant, the two methods of improvisation most commonly described by theoretical treatises, countering also relies on the fundamental practice of creating new parts around an existing plainchant. Countering begins with a plainchant which is first itself highly ornamented; to this ornamented tenor, one to four lines may be added, each using similar procedures to create a decidedly melismatic texture. Although the treatise itself dates to c. 1580, references to countering occur as early as 1447, for example, in an indenture from Durham Cathedral that stipulates that the cantor should teach countering (in addition to plainsong, faburden, pricksong and discant); it is likely that the practice was used throughout the sixteenth century.Footnote 48 As Jane Flynn has demonstrated, ‘counter’ was a skill often taught to choristers as part of their musical education in the latter half of the fifteenth and first third of the sixteenth centuries.Footnote 49 Bisson argues that the fact that there was an established practice of melismatic improvisation among trained singers supports the notion that much of the Eton style could have developed out of basic improvisation, although the examples of countering in the treatise (see Example 3) do not approach the complexity of the writing found in the Eton repertory.Footnote 50

Example 3 An example of three-part countering in British Library, Add. MS 4911, fol. 87v

Whether the works created through countering were notated or not is impossible to know; as they may not have been considered worth saving, they most probably would have been transcribed on relatively cheap paper had they been written at all. However, it requires only a short leap to suggest that a practice like countering (or, for that matter, faburden or descant) might be a first step in the creation of a notated piece of music. Moreover, Bisson’s linking of the Eton repertory to existing English music-theoretical writings offers a tantalising glimpse of what might be learnt about English musical style by examining early Tudor polyphony through the lens of contemporary theoretical writings.

In the present context, it is impossible to examine such a diverse body of repertory as the works in the Eton Choirbook thoroughly. Although most of the choirbook’s contents cannot be precisely dated, biographical information on the composers allows for a relative chronology to be put forward; as such, I have chosen to examine three works that cover a wide chronological period: Walter Lambe’s Gaude flore virginali, William Cornysh’s incomplete Stabat mater and Robert Wylkynson’s nine-part Salve regina.Footnote 51 The last, which was added to the manuscript probably c. 1515, is one of the latest works in the choirbook.Footnote 52 Although Wylkynson’s music was not disseminated widely, it was also in use at King’s College, Cambridge. Walter Lambe, on the other hand, came to Eton as a scholar in 1467. Lambe’s career provides two additional important links with surrounding institutions: following his schooling at Eton he was employed first at Arundel College, and then took up a clerkship at Windsor from 1479 until 1504 or later, except for the period between 1484 and 1492, when he returned to Arundel.Footnote 53 More than most composers whose works are included in the Eton Choirbook, the career trajectories of Lambe and Wylkynson also highlight the extent to which Eton formed part of the central nexus of England’s educational network, as a point from which musical knowledge might be spread to other institutions. Unlike other Eton composers such as Robert Fayrfax and Richard Davy, who undertook university-level study at Cambridge and Oxford respectively and probably never attended Eton, Lambe received his education only at Eton; as such, he must have acquired his compositional training there. Wylkynson, meanwhile, was elected parish clerk of Eton in 1496, and from c. 1500 to 1515 he served as the school’s informator choristarum, where he was responsible for teaching the choristers of the choir and during which time he wrote his Salve regina. Wylkynson, too, is not known to have attended either Oxford or Cambridge.Footnote 54 Yet as I will demonstrate, both composers’ works show knowledge of the compositional techniques found in the Oxford-based writings of Tucke and Dygon. In the case of Lambe in particular, these skills suggest that young musicians at Eton may have received instruction beyond what was typical for choristers at this time.Footnote 55

David Skinner has recently called into question whether the William Cornysh whose music is found in the Eton Choirbook is, in fact, the same William Cornysh who later worked as a famous court composer and playwright, suggesting instead that the Eton composer is the man employed at Westminster Abbey at the end of the fifteenth century. Although the evidence for this suggestion is not conclusive, on stylistic grounds Skinner argues that the works by Cornysh in the Eton Choirbook must be the work of an earlier composer, which would place the date of Cornysh’s Stabat mater in the last quarter of the fifteenth century.Footnote 56 Although scholars often omit incomplete works from examination, I include Cornysh’s Stabat mater because the extant sections show strong links with contemporary theory. Some of the important stylistic features in these votive antiphons reflect the writings of Tucke and Dygon, indicating that composers relied on the strong music-theoretical foundation offered by England’s educational institutions.

the eton repertory and musical proportion

As Theodor Dumitrescu has suggested, the preoccupation with proportions in the theoretical treatises of Tucke and Dygon is mirrored in several Eton works.Footnote 57 Like Dygon, the Eton scribe makes use of four colours, eschewing the theoretical variations Tucke posits in green, yellow, blue, sanguine and purple: black full, black void, red full and red void.Footnote 58 At least fifty-three of the sixty-four extant (complete and partial) works in the Eton Choirbook employ some type of proportional notation, although the extent to which such ratios are used varies considerably in scope and number.Footnote 59 Although Dygon’s overview delves into more complex proportions than can be found in the Eton repertory, there are numerous examples of the ratio of 3:2, or sesquialtera, found throughout this body of polyphony; each of the aforementioned works incorporates this proportional change to a certain degree. Moreover, all three composers employ a 3:2 ratio in multiple (or all) parts simultaneously; in Gaude flore virginali and Stabat mater there are also single part shifts, creating a 3:2 relationship between simultaneously sounding voices. A brief discussion of how Cornysh and Lambe treat proportions will illustrate these relationships in more detail.

In Cornysh’s Stabat mater, there are several extended passages as well as a number of quick three- or four-note figures that relate to the previous section in a ratio of 3:2, and these are found throughout. The prominence of this particular proportion in his Stabat mater, as well as its presence in Wylkynson’s Salve regina and Lambe’s Gaude flore virginali, shows that this relationship played a distinct role in the aural patterns of English polyphony for composers as well as theorists from the mid-fifteenth century into the early sixteenth. Indeed, of the fifty-three works in the choirbook which incorporate some proportional notation, the majority use sesquialtera, with a more limited number using the ratio of 3:1 or, even more rarely, 6:2.Footnote 60 While Wylkynson only employs a 3:2 proportion on the penultimate syllable of the word ‘vulnerato’ in his nine-voice Salve regina, he makes more frequent use of it in earlier works, such as in his five-voice Salve regina, suggesting that he, too, favoured this technique.

Lambe, the earliest of the three composers, shows a complex treatment of proportion in his Gaude flore virginali. As was common, the scribe of the Eton Choirbook uses mensuration signs to indicate proportional changes between different sections of the piece in which all voice parts are involved. The following table shows a breakdown of the sections of Gaude flore virginali according to these mensuration changes; these do not, with the exception of bar 50, line up with phrase breaks in the text:Footnote 61

While the relationships between the first four sections are clear – a standard reading of ![]() C and

C and ![]() B confirms a 3:2 relationship with respect to the division of the breve – the mensuration signs in the last two sections offer an intriguing question about exactly how these parts relate to the piece as a whole.Footnote

62

B confirms a 3:2 relationship with respect to the division of the breve – the mensuration signs in the last two sections offer an intriguing question about exactly how these parts relate to the piece as a whole.Footnote

62

The shift in bar 120 is accompanied by a change to red full and void notation in all parts, with the addition of ‘3·2’ written in only the contratenor part; while red full often indicates sesquialtera, it is only this addition in the contratenor that confirms this reading here. As Magnus Williamson has pointed out in his introduction to the facsimile of the choirbook, the slash through a mensuration sign had no effect on proportional relationships in the Eton repertory, nor does it appear to have served a single function;Footnote

63

the two signs in Figure 1, taken from the opening of Robert Wylkynson’s fragmentary six-part O virgo prudentissima, would map onto one another as 1:1. Thus, it is only the sign in bar 120 in Lambe’s Gaude flore virginali that appears unusual. Yet if Williamson is correct that there is no functional effect of the slash, then ![]() J might just as well be read as

J might just as well be read as ![]() L. If this is true, then a link emerges between the relationship of the mensuration sign in bar 120 and the previous section, and John Tucke’s system of proportional relationships: Tucke designates

L. If this is true, then a link emerges between the relationship of the mensuration sign in bar 120 and the previous section, and John Tucke’s system of proportional relationships: Tucke designates ![]() L to

L to ![]() A as sesquialtera.Footnote

64

Although here the signs instead read

A as sesquialtera.Footnote

64

Although here the signs instead read ![]() J to

J to ![]() A rather than

A rather than ![]() L to

L to ![]() A, Tucke’s system suggests a possible reason the Eton scribe may have used such an otherwise irregular mensuration sign to indicate this particular change, even though Tucke would have read the relationship between these two sections differently based on the presence or absence of a slash.Footnote

65

A, Tucke’s system suggests a possible reason the Eton scribe may have used such an otherwise irregular mensuration sign to indicate this particular change, even though Tucke would have read the relationship between these two sections differently based on the presence or absence of a slash.Footnote

65

Figure 1 Two unlabelled parts from Robert Wylkynson’s O virgo prudentissima

Whereas the aforementioned mensuration sign pairing has perhaps somewhat tenuous links to contemporary theoretical writings, another feature of Lambe’s Gaude flore virginali suggests a strong link to Dygon’s treatise – specifically, to his inclusion of three-part examples to show multiple proportional relationships simultaneously. Unlike Cornysh and Wylkynson, whose music employs a 3:2 proportion between sections only, Lambe offers the singers examples of sesquialtera in terms of the breve, semibreve and minim in a passage noted by Hugh Benham for its proportional complexity.Footnote 66 Example 4 shows how these three levels of the proportion relate to one another.

Example 4 Walter Lambe, Gaude flore virginali, bb. 103–5

These changes are indicated through a variety of means in the manuscript, and in bar 105, both shifts in the contratenor and bassus are indicated consistently, through a continuation of red full notation and the Arabic numerals 3·1.Footnote

67

What is unusual is that the shift in bars 103–4 from ![]() A, which is the same in all three parts, is signalled differently in each line: a mensuration sign (

A, which is the same in all three parts, is signalled differently in each line: a mensuration sign (![]() C) and shift to red full notation in the mean; red full notation and the Arabic numerals 6·4 in the contratenor; and red full notation, the Arabic numerals 6·4, and a mensuration sign (

C) and shift to red full notation in the mean; red full notation and the Arabic numerals 6·4 in the contratenor; and red full notation, the Arabic numerals 6·4, and a mensuration sign (![]() C) in the bassus (see Figure 2 for the original notation).

C) in the bassus (see Figure 2 for the original notation).

Figure 2 Lambe, Gaude flore virginali: (a) mean; (b) contratenor; (c) bassus

This 3:2 relationship between bars 103–4 and the previous section with respect to the division of the breve is quite common in Eton, and there is no reason for the scribe to have been inconsistent in his representation. Furthermore, a more extensive examination of the works in the choirbook shows that red full notation always indicates a sesquialtera proportion unless Arabic numerals indicate otherwise (the most common being 3:1, as occurs in this passage), so the inclusion of Arabic numerals here seems unnecessary. Nevertheless, this brief passage highlights an interest in proportional writing that is mirrored in Dygon’s three-part examples, although on a smaller and less complicated scale.

Magnus Williamson has demonstrated that the works in the Eton Choirbook, with the exception of two pieces by Wylkynson (including the Salve regina), were copied by a single scribe.Footnote

68

Given the relatively short period of copying, the number of strategies adopted for indicating proportional changes is surprising. While mensuration signs are always used to signal shifts that occur simultaneously in all parts, for example between the two halves of a piece, they often appear alongside red full notation to indicate a proportional relationship, as in Figure 2a and c. Figure 3 shows a similar application of this technique, the first proportional shift in the bassus part in Cornysh’s Stabat mater from ![]() B to

B to ![]() D.

D.

Figure 3 William Cornysh, Stabat mater, bassus part

The change to red full notation is a common technique outlined in Tucke’s notebook, found in two of the few passages in English: ‘Red full to blacke full ys sesquealtera 3 | 2 |’.Footnote

69

Moreover, the relationship between the two mensuration signs resembles one of the five relationships Tucke copied for sesquialtera in his discussion of proportional relationships between individual mensuration signs (![]() to

to ![]() A).Footnote

70

Theodor Dumitrescu has argued that the system of proportional mensuration signs outlined in Tucke and Dygon’s writings seems to have had little practical use;Footnote

71

with the exception of mentions of sesquialtera, this seems to hold true. Since the division of the breve (into three versus two semibreves) or the semibreve (into three versus two minims) seems to have been the most common implementation of the 3:2 ratio in the choirbook, the mensuration sign in this case would seem unnecessary; at the very least, there are other instances where the scribe is not so careful to indicate where the proportional relationship exists as he has here. That Tucke copied down this theoretical relationship, and that it exists in practical sources, suggests a use that may have been widespread in the late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century practical sources that no longer come down to us.

A).Footnote

70

Theodor Dumitrescu has argued that the system of proportional mensuration signs outlined in Tucke and Dygon’s writings seems to have had little practical use;Footnote

71

with the exception of mentions of sesquialtera, this seems to hold true. Since the division of the breve (into three versus two semibreves) or the semibreve (into three versus two minims) seems to have been the most common implementation of the 3:2 ratio in the choirbook, the mensuration sign in this case would seem unnecessary; at the very least, there are other instances where the scribe is not so careful to indicate where the proportional relationship exists as he has here. That Tucke copied down this theoretical relationship, and that it exists in practical sources, suggests a use that may have been widespread in the late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century practical sources that no longer come down to us.

The possibility of consistent relationships between mensuration signs in the Eton Choirbook is muddied, however, by an example taken from the first instance of a 3:2 proportion in Lambe’s Gaude flore virginali (see Figure 4). Not only is the choice of ![]() C to

C to ![]() J unusual for designating sesquialtera – neither Tucke nor Dygon suggests it as a theoretical possibility, for example – but the mensuration sign seems superfluous: in all three parts which undergo a shift at this point (mean, contratenor and bassus), the scribe uses red colouration and Arabic numerals alongside

J unusual for designating sesquialtera – neither Tucke nor Dygon suggests it as a theoretical possibility, for example – but the mensuration sign seems superfluous: in all three parts which undergo a shift at this point (mean, contratenor and bassus), the scribe uses red colouration and Arabic numerals alongside ![]() J to signal the change. As the combination of red colouration and Arabic numerals is enough to indicate sesquialtera elsewhere in Eton, the scribe’s use here is redundant. The inconsistency in the methods used by the scribe to identify a sesquialtera proportion, moreover, goes beyond these examples: in addition to sections, often relatively short, where the shift is indicated only through the use of red full notation, there are instances where the relationship is marked by 3·2 without a mensuration sign, or through a combination of red notation and a single Arabic numeral, 3, which can indicate a 3:2 or 3:1 relationship in Eton. From this examination, one must conclude that the scribe carefully copied each work into the manuscript exactly as it came to him, presumably using different sources, each with its own idiosyncratic ways of notating proportions. These ‘errors’ also suggest, then, that while the use of red full notation to express sesquialtera was common throughout England, other techniques to indicate the same ratio were less standardised. Indeed, even within the same work, a number of indicators might have been used to alert singers to a proportional shift, and these changes might have taken place at a variety of different levels.

J to signal the change. As the combination of red colouration and Arabic numerals is enough to indicate sesquialtera elsewhere in Eton, the scribe’s use here is redundant. The inconsistency in the methods used by the scribe to identify a sesquialtera proportion, moreover, goes beyond these examples: in addition to sections, often relatively short, where the shift is indicated only through the use of red full notation, there are instances where the relationship is marked by 3·2 without a mensuration sign, or through a combination of red notation and a single Arabic numeral, 3, which can indicate a 3:2 or 3:1 relationship in Eton. From this examination, one must conclude that the scribe carefully copied each work into the manuscript exactly as it came to him, presumably using different sources, each with its own idiosyncratic ways of notating proportions. These ‘errors’ also suggest, then, that while the use of red full notation to express sesquialtera was common throughout England, other techniques to indicate the same ratio were less standardised. Indeed, even within the same work, a number of indicators might have been used to alert singers to a proportional shift, and these changes might have taken place at a variety of different levels.

Figure 4 Lambe, Gaude flore virginali, mean

Although the relationships in the Eton Choirbook are not nearly so complex as many of those outlined in Dygon’s treatise, the English interest in proportional mensuration stressed in theoretical sources is mirrored in practical examples from the Eton Choirbook. Moreover, the strong connection between some of the methods described in these theoretical treatises and their use in contemporary polyphony, although there are numerous inconsistencies in their application, suggests that English music theory at the turn of the fifteenth century may provide further insight into concurrently copied books of polyphony. Lambe’s use of more complex relationships between parts in Gaude flore virginali, furthermore, provides a practical explanation for why Dygon thought it was important to include examples in his treatise that showed two discant parts in different relationships to the tenor, when Gaffurius had not done so. Yet even the use of a sesquialtera proportion at multiple levels, as in Lambe’s Gaude flore virginali, does not fully explain the interest in proportion found in Dygon’s treatise or even Tucke’s brief discussion. Indeed, this preoccupation with complex proportional relationships appears to have been based in the combined study of musica speculativa and musica practica that was the curricular focus for musicians trained and educated at Oxford and Cambridge.Footnote 72

This possible explanation for these notational inconsistencies is further corroborated by other scholarly work on proportions and mensuration signs and their application in practical sources during this period. In a series of articles, Roger Bray has proposed a relationship between the academic study of complex proportions, their implementation through colouration, and the works composers completed as part of their doctoral degree requirements. One obvious example of the latter still exists, he argues: the anonymous and enigmatic O quam suavis mass. A brief study of Robert Fayrfax’s O quam glorifica, Bray demonstrates, shows it to contain numerous ‘markers’ – including unusual uses of mensuration signs like those discussed above – of a more complex system of colouration.Footnote 73 Bray argues that a number of these learned masses were produced in a complicated, academic format but also ‘arranged’ for performance, as their ‘esoteric’ notation would have left parts such as the tenor of the O quam suavis mass difficult to perform. Significantly, Bray demonstrates that the complexity in the academic format of Fayrfax’s O quam glorifica hinges on its mensuration, and it is the practical difficulty performers might have faced that meant such performing versions were required.Footnote 74 Bray’s working model, however, assumes that these pieces were first composed using a notational form similar to the performance versions that come down to us. Ian Darbyshire argues in his own study of this ‘esoteric’ compositional practice that the complex notation was in fact an integral part of the conception of these works, and that we can reconstruct this form based on the markers or clues left in the existing performance versions.Footnote 75 The suggestion that more complex mensural shifts – among other elements – were removed from this repertory in order to aid in its performance provides further evidence linking the more notationally complicated examples in Dygon’s treatises, the system of mensuration signs provided by both Tucke and Dygon, and contemporary composition, and demonstrates that composers employing difficult proportions were well aware that simplification might be needed in order for their music to be performed.

In his edition of John Tucke’s notebook, Ronald Woodley makes a similar argument concerning Tucke’s discussion of proportions and contemporary polyphony. Relying on Tucke’s description of colouration, Woodley proposes solutions to two complex passages in Thomas Ashwell’s Ave Maria mass, found in the Forrest–Heyther partbooks (Oxford, Bodleian Library, Mus. Sch. e.376–381), in which blue and green notation would allow for a cleaner and less awkward presentation. Given the possible relationship between Ashwell and New College, Oxford, as well as the connection between the Forrest–Heyther partbooks and Cardinal College, Oxford, Woodley argues that these links offer evidence of an intellectual context in which, over several generations, musicians in contact with one another developed the colouration scheme Tucke proposes.Footnote 76 Although Woodley’s evidence suggests a relatively small cluster of musicians, when taken with Roger Bray and Ian Darbyshire’s work on ‘esoteric’ compositional practices this circle becomes wider. Robert Fayrfax’s O quam glorifica, which served as his doctoral exercise at Oxford in 1511 and which Bray and Darbyshire argue originally employed a system of colouration akin to that which Tucke describes, is found in three extant sources: the Caius (Cambridge, Gonville and Caius College, MS 667) and Lambeth (London, Lambeth Palace, MS 1) choirbooks, and the Peterhouse partbooks (Cambridge, Peterhouse College, ‘Henrician Set’ MSS 40–1, 31–2), the latter of whose sources derive from repertory at Magdalen College, Oxford.Footnote 77 Fayrfax’s earlier education, moreover, was undertaken at Cambridge, where he received the MusB in 1501 and the DMus in 1504, during which time he also served as a lay clerk or Gentleman of the Royal Household Chapel.Footnote 78

I do not wish to imply that the majority of the Eton repertory was originally written using the kind of ‘esoteric’ notation that Darbyshire and Bray describe. Indeed, although there are perhaps specific moments that might lend themselves to such an interpretation, on the whole the notational oddities in Eton are best understood as unusual deviations from a system of mensuration and proportional writing that was becoming increasingly standardised in practice. But these notational complexities offer us a glimpse into how the theoretical and compositional training professional musicians received at Oxford and Cambridge also affected the compositional process of ‘standard’, or non-academic, repertory. Although the intricate proportional systems Tucke and Dygon describe were not commonly employed in music intended solely for performance, an education that focused heavily on colouration and mensural relationships to express proportional shifts in academic composition would nevertheless have affected how musicians processed and understood the act of composition, and it is unsurprising that signs of this education would appear in music written for a non-academic purpose. The grounding these composers received in musica practica thus helps to explain some of the more irregular or unusual uses of mensuration signs (and their combination with colouration and Arabic numerals) in the Eton repertory.

Understanding proportional relationships in early sixteenth-century English polyphony as essential to the most sophisticated practice of music composition also offers us a fuller sense of how music was learned and appreciated in early Tudor England. Although the strictly ‘esoteric’ music Darbyshire hypothesises may have been produced only at Oxford and Cambridge, many graduates of these institutions went on to successful musical careers at the regional colleges like Eton and Arundel, where they still produced highly complex works like those in the Eton choirbook. Additional research is needed to reconstruct the curriculum taught to music students at these colleges and universities, but the writings of Tucke and Dygon, the considerable use of proportional relationships in the Eton Choirbook (and elsewhere), and the ‘esoteric’ notational practices uncovered by Roger Bray and Ian Darbyshire all demonstrate that the theoretical interest in proportions in England continued to stimulate or be inspired by practical considerations to a greater extent than was the case for Continental theorists at this time.Footnote 79

MUSICAL NETWORKS IN ENGLAND C. 1500: FURTHER EVIDENCE OF CONNECTIONS

In addition to the central importance of rhythmic proportions for both theorists and the composers of the Eton repertory, there are further musical links between these three sources which point to a shared intellectual environment. In his edition of John Tucke’s notebook, Ronald Woodley considers other practical implications of this theoretical source for the study of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century English polyphony. Specifically, he examines several short passages in which Tucke discusses techniques that might be used for creating musical embellishment. As Theodor Dumitrescu notes, the Greek or pseudo-Greek titles of these devices offer evidence of a university curriculum whose contents included material outside the standard Boethian curriculum.Footnote 80 Woodley stresses in particular the practice of typus or transumpcio, describing Tucke’s definition as ‘potentially one of the most rewarding passages for our understanding and perception of at least one aspect of the music of this period’.Footnote 81 Indeed, Tucke’s discussion of typus helps to explain the elements in early sixteenth-century repertory that are imitative or derived from one another without being related to a specific point of imitation. These passages, which offer suggestions for creating variation from existing material, are similar in concept to Continental writings on imitation. However, they provide a different approach – one that still leads to a type of musical cohesion, but which is not strictly imitative.

Beginning with a group of pitches called the ‘nature’, in typus each pitch is then embellished by a two-note figure that rises stepwise and then returns to the original pitch (see Example 5), which Tucke describes thus: ‘In this way pieces of music can be composed by means of typus in all kinds of prolations.’Footnote 82 Tucke’s use of four different notational forms suggests this is a basic skill that can be applied to any type of composition. Although he uses only two- and three-note melodies in his example, as Woodley points out, the significance of this example lies in the possibilities it suggests for a compositional practice wherein any number of similar formulaic motifs might be employed to add variety to simple counterpoint while maintaining coherence. Indeed, this ornamentation is probably only one example of an entire repertory of formulaic motivic constructions that singers and young composers may have been taught.Footnote 83 Such a practice would not create imitative music, at least in the Continental sense; rather, the music composed using this technique (or variations on it) might have a more general sense of motivic unity.

Example 5 Typus in John Tucke’s Notebook

Woodley discusses the possible ramifications of such formulaic constructions using a short, untexted three-part work by William Cornysh the younger in the so-called Henry VIII manuscript (London, British Library, Add. MS 31922).Footnote 84 Woodley identifies several of the underlying melodic patterns in the piece, demonstrating the ways in which they are ‘composed out’ in a graph that allows the reader to grasp how the motifs work on a larger scale throughout the work. Although it is not always easy to see such patterns in extant works – and in more complex polyphony, similar units are even more difficult to trace – Woodley’s analysis demonstrates a strong connection between Tucke’s theoretical discussion and this contemporary practical example. As Woodley suggests, this technique thus has the potential to shed considerable light on contemporary compositional practices – a particularly valuable prospect, given how few English music-theoretical sources from the early Tudor period remain.Footnote 85

In addition, this technique, alongside the related compositional practice of temporal arsis and thesis discussed below, suggests a further possibility for how music educational techniques spread from centres like Oxford and Cambridge to not only Eton, but further afield, in this case to Higham Ferrers College, Northamptonshire (Tucke’s first teaching appointment) and the Benedictine abbey of St Peter, Gloucester, where Tucke was later employed as lay master of the Lady Chapel.Footnote 86 In each instance, Tucke was probably required to teach choristers the basic techniques typically required in the education of young singers, including several of the following: pricksong, descant, plainsong, faburden and countering.Footnote 87 Yet it is also conceivable that Tucke taught the more skilled of his charges the relatively simple techniques of typus or arsis and thesis, which could be used in improvised as well as written polyphony. As such, these methods offer insight into how the more learned study of music at Oxford and Cambridge might reach those whose education occurred primarily at regional institutions.

Although an exhaustive examination of the ways in which typus might aid in our understanding of even the three works I have selected from the Eton Choirbook is beyond the scope of this essay, a few examples will illustrate how specific compositional techniques can be traced to or explained by this practice. In addition, that such patterns appear in the Eton repertory as well as in Woodley’s example from the Henry VIII manuscript provides further evidence for the network I posited at the beginning of this essay, through which personnel, musical thought and polyphony were probably transmitted around the south-east of England. Indeed, that examples of this nature can be found in a source probably compiled at court, and in non-religious music, hints at a broader transmission of compositional practices such as those in Tucke’s notebook.

As mentioned above, Tucke’s brief example of typus can be understood as a more general method for embellishing an otherwise simple melodic line through the use of stock ornaments or figures. Although the Eton composers tended not to articulate their polyphonic settings into points of imitation, as was common on the Continent, there are nevertheless small motifs or figures that often appear in multiple vocal lines within a given section. Of the three works examined in this study, these figures appear to feature most prominently in Cornysh’s Stabat mater; however, as it is incomplete, an analysis of how such figures are used in multiple parts is impossible. The following discussion, therefore, is focused on Lambe’s Gaude flore virginali.

Although there are only two large sections in Lambe’s Gaude flore virginali, which end in bar 49 and bar 127 respectively, the votive antiphon can be further broken down into smaller parts. Within each of these overlapping sections, in most instances Lambe uses a single, identifiable melodic figure to tie the music together. Not imitative in the Continental sense, these motifs nevertheless unite the otherwise independent polyphonic lines. Example 6 shows three motifs used in four different sections in Lambe’s setting; they are by no means the only such figures, but a sample of the type of figure found throughout these works.

Example 6 Use of motifs in Lambe’s Gaude flore virginali: (a) bb. 11–12; (b) bb. 15–19; (c) bb. 25–7 and 58–60

As can be seen from these examples, such figures are relatively short and hardly innovative. Yet the melodic and rhythmic contours of each do set them apart from one another and they are used specifically to unify individual sections, often through direct repetition in individual lines, as Tucke demonstrates with typus. In addition, although these examples include melodic and rhythmic repetition, there are many examples of purely rhythmic figures being used in much the same way throughout these works.Footnote 88 At first glance, the connection to the type of embellishment explained in Tucke’s definition of typus seems slight – after all, Tucke’s description and example clearly show a single type of ornamentation that can be applied to a series of pitches. Yet it is easy to see how such motifs might be created out of simpler melodic fragments: in these cases, a falling fourth or fifth, or a rising third. In addition, that Tucke discussed such a method at all is highly suggestive. For a practising musician to write down an example – although only one – of a technique in which two or three pitches were turned into a series of motifs suggests that such methods were widespread and well known.

In addition to typus, Tucke describes a second related compositional technique, temporal arsis and thesis: ‘A piece of music stands in temporal arsis when it is sung backwards, and in temporal thesis when it is sung in a contrary manner, by looking at [the notation] a different way round.’Footnote 89 Tucke provides a notated example of each separately as well as in combination using the same melody, O lux beata Trinitas, which is not included in its original form – presumably Tucke would not have needed a reminder of the chant. Furthermore, he links these two practices directly with composition: ‘In this way pieces of music can be composed at pleasure by means of arsis and thesis, as well in plainsong as in measured music, as you wish.’Footnote 90 Just as in his overview of typus, Tucke thus indicates the practical significance of a simple, but important, compositional practice.

On a scale much smaller than the examples in Tucke’s notebook might suggest, arsis and thesis are also at play in Lambe’s setting. Inverted and retrograde figures found in succession or parallel abound in multiple parts; although these are particularly easy to spot in Lambe’s Gaude, they are present in the other two works in this study as well. Example 7 shows two instances of the application of these techniques: (a) is temporal arsis (retrograde) and(b) temporal thesis (inversion); (c) is a combination of the two techniques.

Example 7 Examples of arsis and thesis in Lambe’s Gaude flore virginali: (a) bb. 112–113, showing arsis; (b) b. 80, showing thesis; arsis and thesis

Granted, such a technique need not require corroborating evidence from theoretical sources to be relevant; composers in England had been using melodies in retrograde and inversion for some time. Yet it is important that a writer like Tucke would think to transcribe or define such a practice explicitly, and it suggests that on a smaller scale these techniques were part of the compositional practices taught to young composers. Indeed, Woodley points to similar instances of this practice in his own analysis of the three-voice untexted Cornysh work, offering examples of temporal arsis and thesis on a both broad and a motivic level.Footnote 91

One need not look far for another Eton work with similar characteristics: John Sutton’s seven-part Salve regina incorporates such gestures, shown in Example 8. Sutton employs these motivic ideas more broadly, across larger sections, but the principle remains the same: in each case, a specific gesture is used to create a sense of motivic unity, although the texture is not otherwise imitative. Here, where Sutton begins using a second unifying motif in bar 27, the next section’s motif is combined with that of the first section, shown in Example 8(c). A broader study, no doubt, might be able to find similar patterns not only within a single composer’s output, but in a whole collection like the Eton Choirbook – indeed, Sutton’s second motif (Example 8(b)) and Lambe’s (Example 6(b)) are remarkably similar. Furthermore, as Woodley shows, composers did not limit this type of expansion to the creation of motivic cells that were identical, but rather often incorporated minor variation. Thus, in each of these cases, a number of further examples might be added to the aforementioned motifs if we take such melodic or rhythmic variation into account.Footnote 92

Example 8 Motivic examples in John Sutton’s Salve regina: (a) motif used in bb. 4–27; (b) motif used in bb. 27–80; (c) motifs combined in b. 27

Such a focus on melodic and rhythmic embellishment, however, was not limited in the Eton compositions to motivic development. An examination of the most original part of Dygon’s treatises, his newly composed musical examples, alongside a section of Robert Wylkynson’s Salve regina will show that these new examples are strongly tied to contemporary English compositional practice. Indeed, as Theodor Dumitrescu has argued, these examples were a crucial part of Dygon’s transformation of a Continental work into two specifically English treatises.Footnote 93 Although it is difficult to compare Dygon’s two- and three-part examples to the fuller compositions in the Eton Choirbook, some similarities are nevertheless apparent. One of the defining features Noël Bisson highlighted in this repertory is the variety of cadences used to extend or end phrases. As Bisson has shown, a characteristic feature of many Eton works is the use of internal cadential points to extend shorter segments into a relatively long phrase.Footnote 94 In addition to obvious similarities, such as the general lack of imitation in Dygon’s examples and the melismatic, complex lines that demonstrate each new proportion, it is Dygon’s treatment of cadences that is typically English.Footnote 95

The use of ornamented internal lines to extend a final cadence is nowhere more apparent in the Eton Choirbook than in Wylkynson’s Salve regina (see Examples 9 and 10). In Example 9, the ‘salve’ which closes the second short section of the piece, the most prominent motion occurs in the second contratenor line, though the first contratenor has the final say in bar 20. In Example 10, not only are the entrances of ‘Et Jesum’ staggered so that at most three of the eight parts begin simultaneously, but Wylkynson varies the technique by halting all rhythmic motion in bar 51, only to resume in both the treble and the first contratenor in bar 52. Moreover, the delay of the C♯ in the treble and third contratenor in bar 52 lead to a brightening of the chord following the harmonic resolution. In both of these examples, the internal rhythmic motion does not delay the harmonic progression, either on the penultimate or the final chord – nor are these lines necessary to avoid any contrapuntal errors. Instead, the cadences are simply extended temporally. In Dygon’s treatise, his three-part examples give an indication of this practice of writing overlapping lines to extend (or avoid) cadences. Example 2 above, which indicates a 3:1 proportion in the top line and a 5:1 relationship in the middle, shows how Dygon writes discantus parts that overlap with one another, dovetailing in order to avoid full internal cadences and extending the phrase until all three voices stop. Although the proportional writing in this example eclipses the rhythmic complexity in Wylkynson’s Salve regina, the two lines against one another, if sung, would offer a similar aural cue: in both cases, a listener would hear multiple complex rhythmic lines, overlapping so as to avoid a full close until the end of the section.

Example 9 Robert Wylkynson, Salve regina, bb. 18–20

Example 10 Robert Wylkynson, Salve regina, bb. 49–52

The final cadences in much of the Eton repertory, as Bisson has shown, are also substantially different from their Continental counterparts, in part due to the high level of embellishment found in individual voices after the cadential resolution or on the penultimate syllable. Table 1 shows the number of cadences (harmonic resolutions which end major sections) found in the three primary works examined in this study. The overwhelming majority of cadences that end sections in these three works – over 75 per cent – incorporate embellishment in the form of rhythmic motion in at least some voices on the penultimate or final syllable of a section. Furthermore, the final cadences in Wylkynson’s Salve regina that are not embellished end the smaller, solo sections featuring only two or three voices. Final cadences using all nine parts are all embellished, usually with multiple voices moving independently of one another on the penultimate and final syllables, like those shown in Examples 9 and 10.

Table 1 Final cadences

Dygon’s cadences, despite the preponderance of two-voice examples in his treatises, share this characteristic – indeed, almost every cadence includes elaborate embellishment on the penultimate syllable. In addition, there are also instances where the tenor comes to rest on its final pitch before the discantus voice does the same. Perhaps even more significantly, as Dumitrescu has pointed out, in the only two musical examples Dygon retained from Gaffurius’s original text he rewrote the cadences to reflect typical English practice. Example 11 shows the most overt of these changes: taking a simple, two-note figure in the discantus, Dygon added the type of florid embellishment found in many of the Eton works.Footnote 96

Example 11 Dygon’s embellishment of Gaffurius’s cadential figure

One need only glance at Wylkynson’s settings in Examples 9–10 to understand why Dygon might not have been satisfied with Gaffurius’s unadorned line. That Dygon bothered to write new musical examples at all, moreover, is highly suggestive. Such an undertaking would have required considerable time and effort, and there were no technical reasons to revise or omit Gaffurius’s examples. In creating his own musical settings, then, Dygon took a Continental treatise and made it more accessible to an English audience by presenting music in a familiar style. Furthermore, Wylkynson’s Salve regina is one of the two latest works in the Eton Choirbook, not added to the manuscript until 1515. Given that Dygon’s treatise was almost certainly compiled later in his life, it is unsurprising that of the three works, Wylkynson’s would share greatest level of similarity with Dygon’s examples, even though proportional writing occurs less in his Salve regina than in Cornysh’s or Lambe’s votive antiphons. Finally, this interest in musical practice on Dygon’s part, although perhaps unsurprising given that a small number of extant works can be attributed to him, speaks more broadly to the close relationship between theory and practice in early Tudor England.

CONCLUSIONS

Both educated at Oxford, John Tucke and John Dygon undertook academic study that viewed rigorous intellectual training in music as part of an important educational foundation. The common focus on proportions and mensuration signs found in their theoretical writings, particularly when read in the light of earlier (and later) English treatises mentioning musical proportion, demonstrate that these concepts held a great deal of theoretical value in English musical education. Yet the musical experiences the two men had as students were certainly not limited to lofty theoretical discussions undertaken in the classroom. That these sources both date from the early sixteenth century, when the practice was codified at Oxford and Cambridge of conferring music degrees that combined musica speculativa and musica practica, is certainly no accident.Footnote 97 Although the evidence as to the specific instruction the two young scholars received is scant, as Theodor Dumitrescu has shown, extant contemporary manuscript sources of theoretical writings offer some indication of what this education may have looked like.Footnote 98 Tucke and Dygon’s works themselves also demonstrate that a thorough theoretical and practical education in music could be found at Oxford in the early sixteenth century. Certainly both manuscripts show, although in radically different ways, that the two men paid careful attention to the practical elements of musical composition, learning how to teach basic compositional techniques (such as those in Tucke’s notebook) and write in an English musical style.

What is perhaps equally valuable for modern scholarship is the extent to which these two theoretical manuscripts can offer insight into how we might better understand early Tudor polyphony – a repertory for which we have few contemporary tools to hand. Through careful study of the mensural choices of the Eton Choirbook, it becomes clear that the theoretical interest in musical proportions had a strong grounding in – or was influenced by – contemporary compositional practice. Even the complex system of indicating proportional relationships through mensuration signs that both authors describe finds some (albeit limited) use in practical sources. Roger Bray and Ian Darbyshire’s studies of academic music composition during this period further stress the importance of proportions and mensuration for musicians educated at these institutions. Tucke’s brief descriptions of musical elaboration techniques, and in particular the practice of typus, meanwhile, shed light on the English ‘festal’ style of polyphonic composition that dominated the early Tudor period, and a comparison of these techniques with contemporary polyphony demonstrates some of the ways in which simple melodies might be ‘composed out’ into a florid polyphonic texture. That such compositional techniques can easily be seen as derivative or a close relative of the improvisational practices of faburden, descant and countering used throughout England – and in Scotland – to create simple polyphony well into the sixteenth century is certainly no coincidence. Techniques like typus, then, draw us a step closer to understanding how young composers learned to put their theoretical training into practice, while also offering modern scholars a tool for analysis.

When read collectively, moreover, these two theoretical manuscripts and the Eton repertory afford us a deeper understanding of the specific cultural milieu surrounding the wealthy secular colleges and universities in England during this time. As Clive Burgess and Martin Heale have demonstrated, in their introduction to a recent volume on the late medieval English college, these centres have been largely overlooked in current scholarship on institutions in England in favour of studies of monastic and parish life. As several of the contributions to their volume illustrate, at least by the fifteenth century many of the most influential organised communities were collegiate. These detailed case studies, which examine the wealth of religious, social, cultural, political and economic impact such institutions had on English life, show that more work is needed to understand how these colleges were connected to one another.Footnote 99 As I have demonstrated, the ideas and practices connecting the three manuscripts discussed in this essay – as well as a number of other sources and composers – confirm the presence of a network that allowed for the transmission of musical ideas throughout England, with the south-eastern nexus of Eton, Oxford and Cambridge at its centre. The continuous movement of individuals between these institutions – often from Eton scholar to Oxford or Cambridge undergraduate back to Eton as a fellow – meant that these institutions were particularly important during the early sixteenth century for the transmission of musical thought and repertory. Further confirmation of the extent of this collegiate network no doubt remains to be found at many of the lesser-known institutions in Magnus Williamson’s study, such as Arundel College or Fotheringhay College. Indeed, if David Skinner is correct that both the Caius and Lambeth Choirbooks were compiled at the former, Arundel College may well join Oxford, Eton and Cambridge at the centre of this educational network in the south-east of England.Footnote 100 Ronald Woodley’s discussion of typus in an untexted, three-voice work by William Cornysh in the Henry VIII manuscript, meanwhile, demonstrates that the larger network of musical transmission surely encompassed more than just the provincial (and largely collegiate) institutions which are Williamson’s focus. Whereas the repertory in the Eton Choirbook was written primarily for Marian devotion in chapels and churches, the music in the Henry VIII manuscript has much broader uses. The complexity of the possible patterns of transmission elucidated by the wide variety of connections enumerated above thus indicates that there is much yet to be done to uncover additional details of the musical networks through which English personnel, repertory and musical thought were disseminated. Such a project, however, would considerably expand our understanding of musical life in early Tudor England.