Any forthcoming anniversary of an important historical personage is usually a strong stimulus to revive scholarly interest and presents a good opportunity to revise certain beliefs about various aspects of his/her life and activity. For a musicologist, and especially for one who studies fourteenth-century Italian music, the 700th anniversary of the birth of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV (1316–78) provided an impetus to reconsider the two Trecento madrigals, Aquil’altera by Jacopo da Bologna and Sovran uccello by Donato da Firenze, which have traditionally been viewed as associated with Charles IV’s visits in Italy in 1355 or 1368. Pointedly, these madrigals do not contain unequivocal references to Charles IV: the connection derives from reading the image of the eagle, the protagonist of both pieces, as a symbol of imperial power.

Like many other topics and notions in Trecento studies, the idea of linking both ‘eagle’ pieces with the emperor Charles IV goes back to Giosué Carducci, the first scholar to investigate, in the 1860s, the Trecento musical repertory. The supposed celebratory and adulatory context, however, was countered by Carducci himself, who expressed a rather ironical and sceptical attitude towards his own proposal: ‘the eagle that lost its feathers’.Footnote 1 Such a sarcastic view is discerned even more in Donato’s madrigal, continues Carducci, which likens the Emperor to ‘a merchant who rode to fair on his packhorse, and was chased away with booing’.Footnote 2 Despite this rather critical interpretation Carducci gave to the image of the eagle, his suggestion of Charles IV as protagonist of these madrigals still remains relevant for modern musicology.

The three-voice polytextual madrigal Aquil’altera/Creatura gentil/Uccel di Dio Footnote 3 by Jacopo da Bologna has long interested musicologists for its musical and literary components. According to Nino Pirrotta, the eagle symbolises the imperial dignity, suggesting a connection of this highly ambitious work with the coronation of Charles IV in Milan on 6 January 1355.Footnote 4 Although over the course of time other historical persons have been proposed for the role of the madrigal’s veiled protagonist, many scholars continue to see it as addressed to Charles IV, if not specifically on his coronation in Milan in 1355, at least on one of his two visits in Italy, in 1354–5 or in 1368–9.Footnote 5 Maria Caraci Vela argues that this ambitious composition certainly seems to be associated with an especially important person, no less than an emperor.Footnote 6 The two-voice madrigal Sovran uccello sei fra tutti gli altri by Donato da Firenze, though less studied, is considered a celebratory piece as well, composed on the occasion of one of Charles IV’s two Italian expeditions.Footnote 7

There is, of course, a good reason for linking these madrigals to Charles IV through interpreting the eagle as a heraldic symbol of the Holy Roman Emperors. Here, however, another question emerges about the reliability of the interpretation of Trecento poetic images, above all those of animals and birds, as necessarily heraldic symbols. In this regard the dissertation by Sarah Carleton, ‘Heraldry in the Trecento Madrigal’, is an example. Its chief thesis that eighteen madrigals belong to the category of heraldic pieces represents exactly the problem of taking for granted that the poetic texts are related to heraldry.Footnote 8

In some instances in the musical madrigals, the images certainly could have been planned by their authors as heraldic symbols. But when they were not or not only, what other sources of inspiration and other meanings they could have had? Obviously, deep-rooted tenets (such as this one), accumulated over the long time of musicological research on the Trecento, invite a more critical approach. ‘In particular,’ as Maria Caraci Vela has pointed out, ‘a problem exists with regard to contextualisation: in order to be adequately dealt with, up-to-date interdisciplinary areas of competence are required.’Footnote 9 Such a contextualisation is essential for informed interpretations of musical compositions, especially when relating them to historical personages and events. Therefore, it is worthwhile undertaking the challenging task of exploring the relevant historical contexts, Milanese for Jacopo’s madrigal and Florentine for Donato’s, with a view to placing both pieces. Assuming that they were related to Charles IV’s Italian campaign, one might expect that these madrigals reflect the reaction to it by Italians, expressed, among other ways, in literature and in music.Footnote 10

The Italian adventure of Emperor Charles IV came about as a result of the encounter of two, so to say, counter-desires. On Charles’s part, it was vitally necessary to be crowned emperor of the Holy Roman Empire in Rome by the pope, a coronation which would remain uncontested, unlike the coronation of the King of the Romans, of which he could have been quite easily deprived on the decision of the assembly of the German prince-electors. The ceremony of the coronation of Holy Roman Emperors consisted of three compulsory phases.Footnote 11 Charles IV had already been crowned as Rex Romanorum in 1346, with the first crown, silver, the corona argentea, in Germany (Bonn), as was the custom. In order to complete the procedure he required the two other coronations that needed to be made in Italy: (1) with the iron crown of Lombardy, corona ferrea, which according to the tradition was kept in Monza close to Milan, the ancient royal residence of the Lombard kings; (2) with the golden crown of the Holy Roman Emperors, corona aurea, which was preserved in Rome.Footnote 12

On the part of the Italians, more specifically the inhabitants of Tuscany, the decision to appeal to Charles to come to Italy was caused by substantial changes in Italian domestic politics: the threat of the increasing Visconti expansion towards the Tuscan territories at the beginning of the 1350s, and the gradually weakening support by the papacy of the Guelph communities in Tuscany, above all that of Florence. Pope Clement VI, after having lost Bologna in 1350 and not being able to continue military resistance, made a truce with Giovanni Visconti in 1352, leaving the Tuscan cities on their own. For this reason, in the same year some Tuscan communities, including the traditionally Guelph Florence, decided to seek aid from Charles, the king of Bohemia, as he is most often called in the Italian literature of this period.

The very idea of calling on Charles for help, however, had already been considered at the time. One year earlier, on 24 February 1351, Petrarch wrote to Charles IV his first letter (of fourteen), subsequently included in the Familiares X 1. Petrarch exhorted the king to come to Italy and to extend his authority there, appealing to the institution of the Holy Roman Empire, notwithstanding the fact that this institution had so often disappointed the expectations of the Italians for a better and more consolidated government, one which could have stopped the perpetual wars between the local rulers. Charles responded to Petrarch immediately in his letter Liberata tui, though it reached the great poet much later, explaining that the situation in Italy appeared to be somewhat different and much less idealised in comparison with Petrarch’s description.Footnote 13 However, the new pope, Innocent VI, who succeeded Clement VI in 1352, changed the papacy’s traditionally rival politics towards the Empire; seeking instead to reconcile the papacy with it, he promised Charles the imperial coronation in Rome. This was the impetus for the king of the Romans and Emperor-elect Charles IV to take the road and cross the Alps.

THE MILANESE CONTEXT AND THE MADRIGAL AQUIL’ALTERA

Remembering the disastrous campaign of his grandfather, Henry VII, in Italy in 1310–13, which resulted in a long series of battles that culminated in his death near Siena in 1313, Charles took with him a small group of 300 cavalrymen (compared to the 10,000 of his grandfather), in order not to exacerbate the already explosive situation.Footnote 14 In October of 1354, Charles entered Italy and after some short stays in different places along his way (Udine, Padua, etc.), on 7 November he reached Mantua, where he remained blocked for almost two months until Christmas because of the very difficult negotiations about the right of way through Visconti territories and the procedure of coronation with the Iron Crown in Milan.Footnote 15

While staying in Mantua and planning his further route towards Rome, Charles daily received numerous delegations from different parts of Italy. He rapidly learned that the Lombard League (la Lega di Lombardia, which included some northern cities opposed to Milan) was too weak and disorganised to oppose Visconti ambitions, and that the different Tuscan communities, while pleading for protection against the Visconti, were intriguing against each other. For their part, the Visconti, who since 1313 were the imperial vicars, gradually sought greater autonomy from the institution of the Holy Roman Empire, preferring to become independent rulers and sovereigns, so that Charles’s supposed alliance with the people of Tuscany did not accord with their interests at all.Footnote 16 On 5 October 1354, a few days before Charles IV reached Italy, the Milanese governor, Archbishop Giovanni Visconti, had unexpectedly died. For a short period of less than one year the Milanese territory was ruled by a kind of ‘triumvirate’, consisted of three brothers, Giovanni’s nephews: Matteo II, Galeazzo II and Bernabò.

Towards Christmas, Charles IV finally made an agreement with the Visconti brothers. Historical studies, both ancient and modern, inform us that the coronation took place in the Milanese church of St Ambrose on 6 January 1355. However, the Florentine chronicler Matteo Villani tells us a different story about the somewhat exceptional circumstances and the different place of the coronation, not in Milan, but in Monza (Latin Modoetia), a smaller town not far from Milan, in the cathedral of which the Iron Crown of Lombardy has been kept up to the present.Footnote 17 Villani’s version of the coronation of Charles IV in Monza has evoked great amazement among ancient and modern historians.Footnote 18 For example, Ellen Widder wonders how this discrepancy could have come about, given that Villani was a well-informed and responsible author.Footnote 19 Whatever the reason, the style and quality of his work do not allow us to ignore this source, so that a closer examination of Villani’s writings is necessary.

Matteo Villani’s Cronica and the Diary of Johannes Porta de Annoniaco

Matteo Villani (1283–1363) was a younger brother of the famous Florentine chronicler Giovanni Villani (c. 1280–1348), the author of the Nuova cronaca, a large opus that encompasses the history of Florence, often touching on other parts of Italy and even beyond it, from ancient times to the year of the plague of 1348. On Giovanni’s death, Matteo continued his work. Unlike other chronicles, with their accounts of centuries-old history, Matteo’s narration consists of nine books that describe the events within twelve years only, during his lifetime between the years 1348 and 1360. Villani died in 1363, eight years after Charles’s coronation, when working on book 9 and having reached May of 1360.Footnote 20 Thus, books 4 and 5, concerning the years 1354–5, must have been written even earlier, with a smaller gap of time. His version of the coronation, described in book 4, chapter 39, is given in full in Appendix 1 below.

Interest in the minutest details, into which the author constantly goes, is the main characteristic of Matteo Villani’s work.Footnote 21 Compare, for example, the full account of Charles IV’s visit to Italy from October of 1354 to June of 1355 in the contemporary Cronaca Sanese by Donato di Neri (d. 1371/2), which takes about five pages, whereas in Villani’s it occupies the entire book 4 and the first half of book 5, while the preparatory phases of this visit are described in a number of chapters in books 2 and 3.Footnote 22

Matteo Villani’s detailed accounts are more literary and resemble the Florentine prose we know, for example, from the stories of the Trecentonovelle by Franco Sacchetti.Footnote 23 He was recounting contemporary history, knowing well that many of his readers were themselves observers of those happenings. Moreover, these witnesses served as the main source of his information, as he noted in the preamble to his chronicle:

How deeply Villani was interested in details, basing himself chiefly on the reports of the eyewitnesses, we learn, for example, from the portrayal of the Emperor he delineated in book 4, chapter 74, Della statura e continenza dello’mperadore. The words with which he begins the description of the appearance of Charles IV and his manners make it clear that Villani obtained this information from someone who was present at the royal audience: ‘Secondo che noi comprendemo da coloro, che conversavano intorno a lo’mperadore’ (According to what we have learned from those who had conversations around the Emperor).Footnote 25 The topic of this chapter is a description of such an audience.

Importantly, in chapter 38, Villani speaks about the preliminary agreement between Charles IV and the Visconti, made during his stay in Mantua, that the coronation should take place in Monza.Footnote 26 The idea to go to Monza without entering the city of Milan came from the Visconti themselves, since they were afraid of the presence of foreign military forces, above all those of the League of Lombardy, in their territory. For that reason, they obtained the king’s promise to go there as a private person with a small escort, and completely entrusted to their jurisdiction and surveillance.Footnote 27

Another document of the epoch is of great help in clarifying this intricate situation. It is the Liber de coronatione Karoli IV imperatoris, a kind of diary written by Johannes Porta de Annoniaco (d. 1361), a secretary of the cardinal of Ostia and Velletri Pietro de Columbario, who was appointed by Pope Innocent VI to crown the Emperor in Rome. Porta gives a detail report about the journey of the cardinal from Avignon to Rome, which started at the beginning of February 1355. Although the cardinal and his retinue were absent from the Milanese coronation of Charles IV, the brief information about it and about some other relevant moments is reported by Porta, who cites verbatim the Emperor’s letters he sent to Pietro de Columbario from Mantua and Milan.Footnote 28

It appears from Charles’s letter written in Mantua on 12 December that the negotiations with ‘the noble brothers Visconti of Milan, Matteo, Bernabò and Galeazzo, faithful subjects of Us and the Holy Empire’ about the right of way through their territories and the coronation with the Iron Crown were difficult and not yet completed. The main problem was the armed escort, which Charles needed to reduce substantially in order not to burden the local people, who in turn would have impeded the royal progression, as he writes (‘quin eo amplius eosdem gravari contingeret, quo magis transitus noster sive progressus regius impediretur’).Footnote 29

It is important to note that Charles, precisely in these days in Mantua, asked Petrarch to come there. Petrarch responded with great enthusiasm to the Emperor’s request and arrived in Mantua on 15 December, after a four-day journey from Milan, which is described in detail in the letter to his Lelio (Fam. 19, 3).Footnote 30 In all probability, the great poet, also known as a brilliant diplomat and successful negotiator, was called in to help. If so, he succeeded in this task in less than ten days, since on 27 December he was already back in Milan, perhaps in order to announce the outcome of the negotiations, while the Emperor finally could make his way towards the city. Strangely, Petrarch did not provide any information on Charles’s coronation in Milan, considering the importance of this event in his own eyes and in the eyes of his benefactors, the Visconti. He certainly must have been present there. However, Petrarch did mention the Iron Crown in his letter to, or rather invective against, Charles IV, referring to his quick escape from Italy in June of 1355 after the coronation with the Golden Crown of the Holy Roman Emperors in Rome: ‘Istud ferreum, illud aureum dyadema’ (This crown iron, the other golden), Fam. 19. 12.

As Matteo Villani recounts, Charles IV left Mantua after Christmas and entered the Visconti domain with fewer than 300 cavalrymen, many of them weaponless, accompanied by a large convoy of armed Visconti men, headed by Galeazzo Visconti. In every city or castle where they stopped, the gates were closed and well guarded. When Charles arrived at the Abbey of Chiaravalle, between Lodi and Milan, he was greeted there by Bernabò Visconti. After a decent dinner in the Abbey, Bernabò invited him to visit Milan, in view of the fact that the king had no armed men of the League in his retinue. The invitation, thus, was unplanned and spontaneous. According to Villani, the king was forced (‘li costrinsono’) to accept this proposal, and when he entered Milan he ‘almost could not have seen anything other than armed men on horseback and servants’. The military parades the Visconti displayed in his presence were accompanied with the very loud music of numerous military bands: ‘The sounds of the numerous large and small trumpets, nakers, bagpipes and drums were so deafening that one could hardly have heard the loudest thunderclaps.’ The Visconti strove to impress upon the Emperor their wealth and power, ‘to the great suspicion and dread of the Emperor-elect, who seeing himself, with great anxiety, surrounded with a solicitous guard, now wished to be elsewhere and with lesser honour’. Thus they confirmed an astrological prognosis of Ugo of Città di Castello, a Dominican friar and astrologist, that the imperial Eagle would yield to the Viscontean Serpent.Footnote 31 Some days later, on 6 January, continues Villani, the Emperor-elect was brought to Monza for the solemn ceremony of coronation and was crowned there with the Iron Crown of Lombardy as King of the Italians. When he was back in Milan, constantly under surveillance by the armed guards of the Milanese rulers, he hastened his departure in order to free himself of their guard: ‘The king accelerated his course, not like an emperor but like a merchant who is in hurry to get to market, until he left their domain, thereby freeing himself from their convoy.’

Villani describes the general atmosphere surrounding Charles IV’s visit in Milan as full of tension and distrust, indeed ill-befitting the supposed festive and solemn nature of a coronation. This description, it seems, turns out to be quite gloomy not only because of Villani’s own literary style, indeed more pessimistic than that of his brother Giovanni, possibly also because it transmitted the personal impressions of Villani’s oral sources.

The above-mentioned letters of Charles IV, cited by Johannes Porta, also reflect the tense atmosphere of this episode. The emperor constantly begged Cardinal Pietro de Columbario to hasten his arrival in Italy, since it was dangerous to wait too long.Footnote 32

Although Charles IV, in his letter written in Milan on 9 January, is too laconic to describe his coronation, which, in his own words, took place in Milan in St Ambrose’s church, he adds a new detail to the entire picture:

Charles mentions the triple coronation of the Holy Roman Emperors and speaks about the Iron Crown of Lombardy as the second one. We learn from his own words that he should already have been present in Milan on 1 January, the day he was assured to be crowned;Footnote 34 however, ‘for certain reasons’ (ex certis causis) the coronation was postponed to 6 January, the day his grandfather Henry VII was crowned.Footnote 35 Bearing in mind the original intention to perform the coronation in Monza, where the crown was kept, and that the decision to enter Milan was made, according to Villani, at the last moment (in the Abbey of Chiaravalle, between Lodi and Milan), this delay could well have been forced by the necessity to settle certain formalities and to bring the crown from Monza to Milan. It is quite probable that within these five days Charles participated in the trip to Monza in order to borrow the crown from the St John church and to visit this holy place, as he later did in Rome and everywhere on his way, according to the report of Johannes Porta and several other sources.Footnote 36 This could well have been the reason that Villani was actually informed, by his oral sources, about the voyage of Charles to Monza. The ceremony of coronation itself was then performed in Milan, of which Villani apparently remained unaware.

Following Villani, Charles escaped from the Visconti domain as quickly as he could, ‘like a merchant who is in hurry to get to market’. This is the context from which the quotation used by Carducci was extracted, but he interpreted it as follows: like a merchant, the Emperor came only with the intention to collect money and to leave thereafter. This opinion appears in many historical studies, and is used to illustrate Charles IV as a man avid for the money received for the privileges and promises he generously ladled out.Footnote 37 Later, in June 1355, when Charles left Italy quite soon after the coronation in Rome with a great amount of money he had collected, this view turned out to be true. It was not by chance that Villani used this association in his chronicle; but in the given context the comparison of the king with a merchant served Villani mainly to render the king’s fear and anxiety, caused by the Visconti’s frustrating hospitality, from which he wanted to escape as soon as possible, even to the detriment of his imperial dignity. With the same speed Charles returned to ‘Allamagna’ (Germany), avoiding the large cities of the League, where he was no longer welcome, and of course the Visconti territories, where he was hardly allowed to enter, as for example in Soncino.Footnote 38

Aquil’altera for Charles IV?

Maria Caraci Vela has rightly pointed out that it is difficult to see the commission of the madrigal Aquil’altera as an initiative urged by the Visconti, since such a solemn commemoration of an imperial function ill befits the Visconti’s behaviour towards the Emperor.Footnote 39 How little enthusiasm they had regarding the Emperor’s presence on their territory and his coronation in Milan we can infer from the very fact that they made him wait in Mantua for almost two months, until they had found a satisfactory solution. Furthermore, it would have contradicted the Visconti’s own monarchical aspirations. Hence, in the light of Villani’s account, the compatibility of Jacopo’s Aquil’altera with the ambience of Charles IV’s Milanese journey, somewhat doubtful beforehand, now seems even less believable. It comes as no surprise that modern musicologists began to look for different occasions or even for different persons for the role of its protagonist.Footnote 40

In a later work, Nino Pirrotta, though continuing to relate this madrigal to the first visit of Charles IV in 1355, now linked it to the coronation in Rome, not that in Milan.Footnote 41 Caraci Vela suggested that this madrigal could have been written for Charles’s Italian sojourn of 1368–9.Footnote 42

There are at least two difficult points with a change of place and/or time in reference to the madrigal Aquil’altera. The first makes it necessary to remove Jacopo da Bologna from the Milanese milieu and place him elsewhere. Blake Wilson suggested that he might be identified with a certain Jacopo da Bologna documented as a singer in the records of the Laudesi company of Orsanmichele in Florence in 1373.Footnote 43 But was there only one Jacopo from Bologna who could sing? There is no indication that the virtuoso composer Jacopo ever stayed in Florence. Moreover, it hardly seems likely that Filippo Villani, in his book about famous Florentines, who does talk about the great Bolognese maestro Jacopo (in relation to Giovanni da Firenze), would have not mentioned his presence in Florence, if he were there.Footnote 44 Actually, we know nothing of Jacopo’s whereabouts after the 1350s, the years he passed, in all probability, in Milan, nor whether he was alive in the 1360s and later.

The second point concerns the purely Italian genre of the madrigal and the Italian language chosen to celebrate, as it were, a person without a solid Italian educational background, such as the emperor Charles IV. It is all the more strange for a musician like Jacopo, who before then had already proven himself able to compose celebratory Latin motets with devices and acronyms incorporated in their texts: Lux purpurata/Diligite justitiam and Laudibus dignis (transmitted anonymously), both for Luchino Visconti (died in 1349).Footnote 45 In her analysis of the verbal structure of the madrigal Aquil’altera, Caraci Vela demonstrated the strong dependence of its vocabulary on Dante’s Comedy, with which the madrigal shares several expressions and allusions.Footnote 46 It seems indeed unlikely that the addressee of such a refined poetic work, deeply rooted within the Italian literary experience, where Dante’s Comedy served as a foundation and a model, could have been a foreigner unacquainted with the great Italian epic.Footnote 47

The multifaceted world of images and ideas, as it appears in the texts of Jacopo’s compositions, certainly reflects Jacopo’s ample education and deep knowledge of contemporary literature and also his own literary talent. The eagle, besides the traditional view of it as a heraldic symbol of political sovereignty (also nicely harmonising with the Visconti’s own aspirations), actually had various meanings in medieval literature. Jacopo’s madrigal uncontestably praises the mental supremacy of the eagle, which is able to distinguish between true and false, perfection and poor imitation, etc. Exactly in this quality the eagle appears in the bestiary that comprises part of the long poem Acerba by the early Trecento Florentine poet, philosopher, physician and alchemist Cecco d’Ascoli (who ended his life at the stake in 1327, burnt together with his books), symbolising the human intellect, without which one cannot reach the Divine Wisdom.Footnote 48 Of course, it is impossible to ascertain whether Jacopo founded his idea of the eagle as a symbol of intellectual power specifically on this poem, though it was very popular, judging by the large number of contemporary manuscript copies of it. However, in another source, chronologically and geographically much closer to Jacopo, a similar allegory uncontestably surfaces. Surprisingly, it relates in some way to Charles IV’s milieu.

The Chancellor of Charles IV Jan ze Středy (Johannes Neumarkt, 1310–80), the earliest Czech humanist and one of Petrarch’s friends and correspondents, also took part in Charles’s retinue on his voyage in Italy in 1354–5. Petrarch met him personally in Mantua in December 1354, then in Milan and in 1356 in Prague. They exchanged a number of letters, giving evidence of their sincere mutual esteem. One of Petrarch’s letters to Jan ze Středy (Extravagantes 29, misc. 12) was written in Milan on 25 March 1355, between the Milanese and Roman coronations. Charles stayed with his court in Pisa from 18 January to 22 March, and later in Siena. Petrarch wrote:

Although there is no mention of the eagle in this excerpt, the image of its talent (in this context, expressed in the sharp intellect and the ability to learn notwithstanding the surrounding unfavourable conditions) that floats on its wings (alis ingenii) towards the open summit of the truth (apertam veri speculam) is similar to that one of Jacopo’s Aquila: ‘salire in alto’ (to climb high) to ‘la vetta dell’alta mente’ (the summit of the lofty mind), where the ‘vera essenza’ (true essence, or truth) is revealed.Footnote 50 This metaphor goes back to the medieval notion of arx mentis – fortress or citadel of mind – known already in the Carolingian epoch.Footnote 51 But in Ascoli, Petrarch and Jacopo, we see a fusion of the medieval arx mentis with the idea of the flying thought, to which the allegory of the eagle fits well.

Elsewhere I suggested that Giovanni Visconti, archbishop of Milan and its governor from 1349 to his death in October 1354, was the possible addressee of and source of inspiration for Jacopo’s Aquil’altera.Footnote 52 The allegorical connection of the image of the eagle with Archbishop Giovanni, besides the points discussed above, certainly relevant to him, is due to one more factor as well. This connection would remain incomplete without the consideration of Jacopo’s motet Lux purpurata, which contains the acrostic of Luchino Visconti in the triplum, while Giovanni is named in the motetus as presul, bishop. Here an extremely sophisticated hint at the eagle is given in the phrase Diligite iustitiam, qui iudicatis terram (in the motet is last word ‘terram’ was replaced with the word ‘macchinam’). The quotation stems from the Proverbs of Solomon, but Dante in his Comedy describes it in his vision, in which the last ‘m’ of the word ‘terram’ is transformed into an eagle (Par. 18, vv. 89–108). In the motet Lux purpurata, Jacopo obviously alludes to this episode, familiar to any educated Italian of that period, thus connecting the hidden image of the imperial eagle with the brothers Visconti and with their wise government. Furthermore, the fact that the Visconti, namely the father and three of the five brothers, bore the names of the four evangelists (father Matteo and brothers Marco, Luchino and Giovanni), could well have associated the eagle, as the symbol of the evangelist John, with Giovanni Visconti through the obvious onomastic lineage.

The idea of reading the image of the eagle in Aquil’altera specifically as the symbol of the evangelist John was recently supported by Andrew Hicks, who suggested its closest affinity in Jacopo’s madrigal (and in other quotations cited above) with the Homilies on the Prologue of the Gospel of John, written by John Scotus Eriugena in the ninth century:Footnote 53

The most refined theological mysticism of this opus cannot distract us from the spectacular image of the high-flying eagle as an allegory of ‘an indescribable flight of mind into the secrets of the one origin of all things’. Since Eriugena’s Homilies were well known in medieval Italy, judging by the high number of surviving manuscripts of Italian origin dating back to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries,Footnote 55 one can assume that Eriugena’s conception of the eagle could well have served as a source of inspiration for all the authors cited above: Ascoli, Petrarch and Jacopo.Footnote 56

However, in these authors, especially in the latter two, the theological focus is much less pertinent. In the mid-fourteenth century, the new tendencies of burgeoning humanism were becoming discernible, and for Jacopo da Bologna they should have been even more palpable in the immediate vicinity of the greatest poet of the time and the first humanist, Petrarch. Although we almost have no secure chronology of Jacopo’s activity, his presence at the Milanese court of the Visconti in the years of our interest, 1354–5, that is, together with Petrarch, is quite certain.Footnote 57 It is difficult to imagine that Jacopo could have remained insensitive to Petrarch’s influence. Indeed, the above-cited excerpt from Petrarch’s letter to Jan ze Středy is nothing else than a panegyric to humanist studies (pointing to Helicon). Similarly, Jacopo’s madrigal Aquil’altera now appears to be a eulogy of the human mind as well. Giovanni Visconti, called by Petrarch Italicorum maximus for his lofty intellect, comprehensive knowledge and wide interests,Footnote 58 could well have been the source of inspiration for Jacopo, all the more so in that his name so fortunately alludes to the evangelist John’s eagle. From this viewpoint, this madrigal can be seen as one of the first articulations of the conception of humanism expressed through music.

The Music at the Ceremonies of the Coronation in Rome and in Milan

But what of the music that would have accompanied the coronation of Charles IV? Villani gives some idea about the musical entourage of Charles’s Milanese sojourn. He informs us about the abundance of various military bands that accompanied military processions and parades. They consisted of big and small trumpets, nakers, bagpipes and drums, whose sound was very loud and flamboyant (‘gran tumulto di stormenti’ – ‘great noise of musical instruments’), much stronger than the most powerful thunder.

An analogous portrayal of the musical accompaniment of the Roman ceremony as a deafening and intolerable acoustical experience is given by Johannes Porta:

Astonishingly, both Villani and Porta mention the simultaneous playing of different kinds of music, apparently by several ensembles of different musical instruments, nearly at the limits of cacophony, comparable in both cases with a thunderstorm.Footnote 60

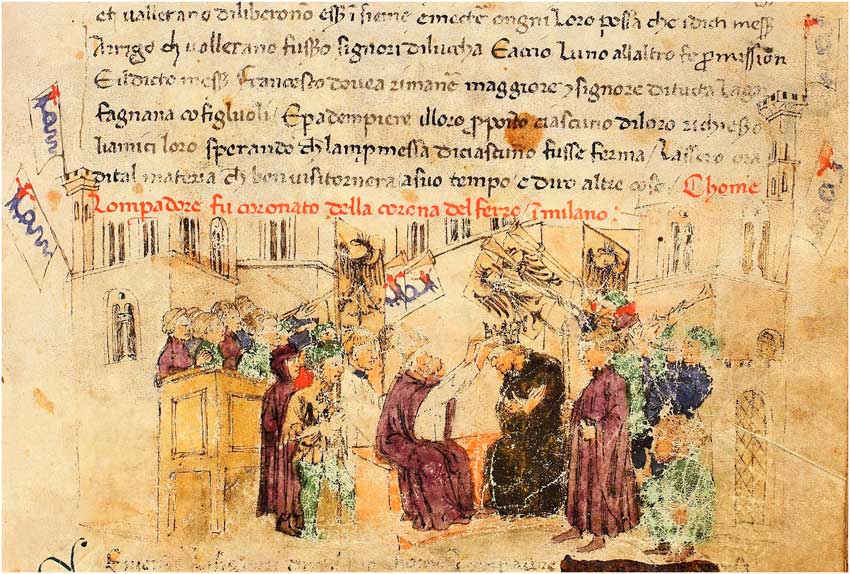

Villani’s and Porta’s vivid reports are supported by illustrations in another contemporary source, the Croniche by Giovanni Sercambi (1348–1424) from Lucca,Footnote 61 a richly illuminated manuscript (574 miniatures, two illuminated initials and 94 blazons and heraldic insigniaFootnote 62 ) of about 1400, kept in the Archivio di Stato in Lucca (MS 107). The paternity of this manuscript still remains under investigation:Footnote 63 some scholars do not believe it is Sercambi’s autograph, while the others, including its recent editor Giorgio Tori, assume the high probability that it was not only copied but even illustrated by the author himself.Footnote 64 Of course, the conditional character of these illustrations must be taken into account, but the pictures undoubtedly reflect a definite conception the illustrator had regarding the events, circumstances and personages.Footnote 65 Sercambi was a child of about 7 years old when Charles visited Lucca in 1355, but he was an adult witness of his second visit in 1368–9, being then at the age of 20 or 21, when he ostensibly started to work on his Croniche.Footnote 66 Therefore, some details in his miniatures dedicated to Charles IV deserve more scrupulous attention.

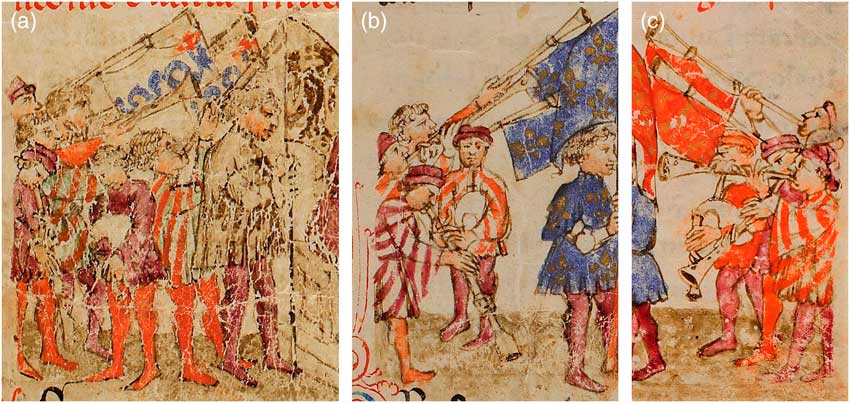

Sercambi depicts several kinds of wind instrument ensembles, the predecessors of the later alta cappella, used in various ceremonies: the conferring the title of duke on the Milanese ruler Giangaleazzo Visconti in 1395 (Figure 1a); the truce in Paris between Richard II of England and Charles VI of France in 1396 (Figures 1b and 1c). The following loud instruments are clearly recognisable here: (1) the straight trumpets with banners, namely the signalling instruments, which produce natural scales and in a certain sense could replace the percussion; (2) the shawms of different sizes, like the bass shawm, or perhaps a bombard or piffaro, clearly visible with its fontanelle in fig. 1b; (3) the bagpipes as an instrument used in ceremonial music (recall Villani’s cornamuse in the military ensembles).Footnote 67

Figure 1 Wind instrument ensembles illustrated in Giovanni Sercambi, Le croniche, Archivio di Stato, Lucca, MS 107, fols. (a) 143r, (b) and (c) 147r (details). Reproduced with the permission of the Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo; further reproduction prohibited

Two pictures illustrate the two coronations of Charles IV, in Milan and in Rome, both accompanied with musical instruments as well. The scene of the Roman ceremony of coronation (Figure 2) presents, on the right side, the Emperor and Pope Innocent VI’s proxy, the cardinal of Ostia, Pietro de Columbario (in the red mantle and the papal tiara), with a group of cardinals in their typical hats, the large red galeros. On the left side, the public watch from a balcony. The group in the middle includes (a) musicians blowing two straight trumpets with the imperial banners and two shawms, one of which is larger than the other; (b) standard-bearers and guards; (c) members of Charles’s retinue. As for the latter, the two figures wearing long cloaks with open sleeves, apparently tabards, and round hoods with scarfs under the chin, appear also in the scene of the Milanese coronation.

Figure 2 The Roman coronation of Emperor Charles IV in Giovanni Sercambi, Le croniche, Archivio di Stato, Lucca, MS 107, fol. 53r . Reproduced with the permission of the Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo; further reproduction prohibited

The Milanese coronation (Figure 3) was performed by the Milanese archbishop Roberto Visconti, who is portrayed with the episcopal mitre in the middle of the scene. On both sides of the Emperor and the archbishop are Charles’s same courtiers and probably one of the brothers Visconti to the right of Charles. On the right is the same musical ensemble, consisting of two straight trumpets with banners with the imperial eagle and two shawms. On the left side, on the balcony full of the spectators, is another pair of straight trumpets with banners with the Visconti viper. Possibly, the abundance of Visconti flags was intended to render an idea of Visconti predominance. In this, Sercambi’s illustration nicely accords with Villani’s description of the atmosphere of the Milanese sojourn of Charles IV and with the prophecy: ‘His imperial soul completely succumbed to the will of the Milanese tyrants, and the Eagle surrendered to the Serpent.’

Figure 3 The Milanese coronation of Emperor Charles IV in Giovanni Sercambi, Le croniche, Archivio di Stato, Lucca, MS 107, fol. 52r . Reproduced with the permission of the Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo; further reproduction prohibited

In the Milanese ceremony there is one figure who lends the entire scene an even more courtly secular character: the sitting man curled up in the right bottom corner (Figure 4).Footnote 68 Almost certainly he can be identified with a jester, the only category of courtiers who could remain sitting on the floor in the king’s presence, especially during a ceremony of strict etiquette, such as a coronation. There was such a buffoon in Milan, related to Charles IV: the Florentine Dolcibene de’ Tori was crowned by the Emperor as king of buffoons. In his essay about Dolcibene (1928), the prominent historian of Italian literature Ezio Levi recorded some other earlier instances of the coronation of buffoons by kings, presenting Dolcibene’s case as the last one in line with this tradition.Footnote 69

Figure 4 Detail of the Milanese coronation of Charles IV in the engraving by Angelo Ardinghi after Sercambi (fol. 52r), 1886

The most likely occasion for Dolcibene’s coronation by Charles IV would have been in Milan, between 6 and 10 January 1355, after Charles’s own coronation. This suggestion accords with the information from Matteo Villani’s account: when Charles returned to Milan after the ceremony in Monza (where Villani supposed the coronation took place), he created some people knights:

This ceremony of creating knights thus included a carnival element as well, namely, the coronation of a buffoon by an emperor. This story became widely known, as many literary sources and even administrative documents testify;Footnote 71 therefore it is not surprising that in his Croniche Giovanni Sercambi added the figure of a buffoon, considering it as relevant within the context of the Milanese coronation of Charles IV.

Having done this, Charles IV proceeded farther on towards Tuscany.

THE FLORENTINE CONTEXT AND THE MADRIGAL SOVRAN UCCELLO

According to Matteo Villani, Charles IV arrived in Pisa on 17 January 1355, earlier than he had planned.Footnote 72 There he remained for a while, waiting for the arrival of the cardinal Pietro de Columbario, who started his slow journey towards Italy on 9 February, reaching Pisa only on 12 March.Footnote 73

In Tuscan territory, the Emperor-elect’s journey was even more complicated than in Lombardy, owing to the irreconcilable controversies between the different Tuscan city-states and the rivalries of numerous clans and parties within the cities, even those where the Ghibelline sympathies were predominant, as in Pisa. Charles’s two main concerns during the negotiations with the different Tuscan communities were a secure journey towards Rome and the gathering of a sufficient amount of money to support his venture and his retinue.Footnote 74 The latter was substantially enlarged because of the arrival of Charles IV’s consort, Anne von Schweidnitz, who joined him in Pisa on 8 February, as Giovanni Sercambi informs us, with more than 4,000 armed horsemen of her party.Footnote 75 One of the illustrations in Sercambi’s chronicles depicts the cavalcade of the imperial cortege of Anna von Schweidnitz arriving in Lucca, on her way to Pisa (Figure 5). Interestingly, a musical ensemble similar to that which appears in the scene of the coronation in Milan heads the procession entering the city gate.

Figure 5 The Empress Anna von Schweidnitz arriving in Lucca in Giovanni Sercambi, Le croniche, Archivio di Stato, Lucca, MS 107, fol. 53r. Reproduced with the permission of the Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo; further reproduction prohibited

Matteo Villani too notes how large the Empress’s cortege was:

the Empress took the road with one thousand noble armed horsemen and many barons in her retinue, in order to reach Pisa, and likewise many clerics and great lords of various provinces of Germany came too, every one accompanied by a large cortege, to come to Italy and to be present at the Emperor’s coronation in Rome.Footnote 76

As in Lombardy, the Tuscans were suspicious of the armed imperial troops, and the Guelf Florence did not look favourably on Charles’s voyage in Italy. Therefore it is not surprising that the preliminary contacts of the Florentine Commune with the Imperial chancellery were held in secrecy from their very beginning in the winter of 1351–2, according to Villani.Footnote 77 Consequently, the Empress’s wish to visit Florence was not honoured by the rectors of the Commune, who did not trust their own citizens, especially the common people (popolo minuto). Their fear was not only that they would hurt the Empress, but they might revolt against the rectors themselves.Footnote 78

Nevertheless, since Pisa was not capacious enough to lodge all these crowds, many of the guests were accommodated in different places, even in Florence, though well guarded:

Franco Sacchetti’s sonnet Firenze bella, confortar ti déi [XII] provides evidence that the Florentines were not happy with this situation. In Sacchetti’s autograph codex Ashburnham 574 (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence) it is placed at the very beginning (number 12).Footnote 80 Franca Brambilla Ageno dates it to the year 1355, when Sacchetti was a young poet in his early 20s. The sonnet appeals to the beautiful city of Florence, which has citizens of every sort, in age (old, adult, young, infants) and ethnicity (Turks, Jews, Greeks, French, judging by their appearance and clothes), and also is accustomed to host various mercenaries, soldiers and horsemen from everywhere. But if Florence wants to respect itself, it must make an effort and chase away the crowds of the Emperor: ‘Però mettiti in via / a contastar compagna e ’mperadore, / e questi manda fuor, se vuogli onore.’ Footnote 81

In these last lines of the sonnet Ageno sees an allusion to Charles’s first visit to Italy in 1355, but the compagna she relates to another event that happened one year earlier.Footnote 82 Yet, by associating this sonnet with the information given by Villani, it would appear that Sacchetti was more specific, addressing his sonnet to this concrete event, namely to the accommodation of part of the enormous imperial retinue in Florence, all the more since Matteo Villani too uses the word compagnia several times specifically to indicate the cortege of the Empress.

At this point we encounter an interesting and important aspect of Charles IV’s Italian adventure: the immediate reaction of the Italians to it. Differing from the chronicles, reflecting more restrained and more pondered reports of past events, the poetic production was more emotional and more spontaneous. It is difficult to say how many such compositions there were at the time, but a certain number of them have survived to our days. What follows below is a short survey of some poems inspired by Charles’s Italian campaign.

Hopes and Disappointments

The arrival of Charles IV in Italy was eagerly awaited by many Italians, as expressed in a number of Petrarch’s letters to the Emperor, mentioned earlier.Footnote 83 Two poetic compositions illustrate these expectations. The poem O sacro imperio santo by Antonio Beccari da Ferrara (1315–c. 1371/4), a renowned poet who served at various courts in Italy, constantly travelling between them, is a ballata grande.Footnote 84 It consists of ten strophes with a ripresa of four lines, two piedi of two lines each, and a volta of four lines, which combines hendecasyllables and settenari (seven-syllable lines) with the rhyme scheme aBbA CdCd dEeA. Judging by its content, the ballata was written before Charles IV’s coronation in Rome or even before he had entered Italy. The poem is an allegorical appeal in the name of Italy, represented as a lonely widow, to the institution of the Holy Roman Empire and to her promised consort, Emperor Charles, who will protect her from any disaster and restore her honour and glory. This is the recurring motif of the ripresa: ‘O sacrosanct Holy Empire, o just Charles, my dear defender, with your long-standing virtue turn your ears to my devout complaint!’ (vv. 1–4: ‘O sacro imperio santo, / o giusto Carlo, o mio bel protettore, / col to antico valore / porgi le orecchie al mio devoto pianto’). After the description of various calamities that were constantly befalling her for a long time, Italy says that all, either Guelph or Ghibelline, desire to see her protector (v. 47: ‘e ’l guelfo e ’l ghibellin veder te brama’); Rome, the Duchy (Lombardy), Tuscany, Romagna, Ancona, Treviso and Friuli will be happy to host the Emperor. The simple citizens who suffer from the local tyrants will feast the Emperor’s coming, as a just and impartial lord (vv. 61–2 and 66: ‘I popol sottoposti a tirannia / chiaman el tuo venire . . . che se’ giusto segnor e naturale’). Italy swears that only the Emperor’s presence in sweet Florence will make thoseFootnote 85 weep who now live in song (vv. 74–6: ‘Perch’io te giuro che sol la tua presenza / ne la dolze Fiorenza / tal farà pianger che mò vive in canto’). Thus, the Emperor must hasten his way towards her. Antonio’s hopes for Charles were indeed too optimistic, reflecting a certain desperateness in the general situation of Italian political and social life, which could only have been resolved by a miracle, like the appearance of a deus ex machina.

Another eulogy of Charles IV is the so-called Canzone di Roma (Quella virtù che il terzo cielo infonde). Ezio Levi formerly attributed this poem, based on its elevated poetic quality and its popularity at the time (judging by the number of the manuscripts containing it, twenty-nine), to Bindo di Cione del Frate, a citizen of Siena.Footnote 86 Levi persuasively demonstrated that the poem was written after Charles’s coronation in Rome on 5 April 1355, but apparently before the Emperor had left Italy in June. This poem describes a night vision, in which a noble but poor woman appears before the author as an allegory of Rome deploring her miserable condition: there is nobody to defend her, neither her Charles, who left after having had her in his possession (vv. 127–8: ‘Or come arò da mio Carlo soccorso, / che m’ha lasciata avendomi in balia?’).Footnote 87 The woman-Rome pleads with the author to convince ‘quell Buemmo’, if not to come back, at least to appoint a worthy king in Rome.

In the same vein as Bindo di Cione, another Tuscan poet, Buonaccorso da Montemagno il Vecchio (c. 1313/16 to before 1390), expressed his almost forlorn hope of Charles’s return in Italy in his sonnet addressed to the Emperor:

Inclita Maestà felice e santa,

ch’è di tua gloria e di tua gran virtute?

O disiata sol nostra salute,

o sacro Carlo, che sì bella pianta,

fama del tuo bel nome eternal, lassi?

Illustrious Majesty, happy and sacred,

what happened to your glory and your great virtue?

O our only desired salvation,

o sacred Charles, why do you leave such a beautiful flower [Italy],

which constitutes the glory of your eternal beautiful name?Footnote 88

Apparently, this sonnet too was written after the Emperor had left Italy in June 1355.

The Emperor’s departure irritated not only his open antagonists, who were not lacking in Italy, but even his most ardent supporters. An excellent example of such a ‘change of mind’ is the sonnet by the poet mentioned earlier, Antonio da Ferrara, ‘S’a leççer Dante mai caso m’accaggia’, in fact a sonnet of correspondence with Menghino Mezzani (c. 1290s to 1376), a notary of Ravenna and a person very knowledgeable in poetry.Footnote 89 Antonio, a former enthusiast of the imperial government of Italy, now addressed the Emperor with the most harsh and offensive words. Interestingly, the sonnet contains a quotation of three verses from Dante’s Comedy (Purg. VI, 97, 98 and 100), where ‘Alberto Tedesco’, namely the Holy Roman Emperor from 1298 to 1308 Albert I of Austria, is recorded:

Menghino responds to him with the sonnet ‘Non basta lingua umana ch’è più saggia’ in the same rhymes,Footnote 91 as was the custom, praising Antonio’s clever language and argumentation with which he described the shameful behaviour of Charles IV, although human language cannot do that better than Antonio’s (‘Non basta lingua umana ch’è più saggia, / con quanto può la tua, o Mastro Toni, / se del nuovo Re Carlo il ver mi suoni, a sì notarlo che vergogna n’aggia’). Moreover, the higher the expectations aroused by an elevated person, the greater the insult he caused. Menghino likewise quotes from Dante’s Comedy (Inf. I, 101–5), saying that he too wanted to see in Charles the saviour of miserable Italy (‘volsi nominarlo / qual Veltro a dar salute a Italia umìle’), who is not interested either in lands or in money (‘che terra o peltro non dovea cibarlo’).Footnote 92 But he turned out as ungrateful and cowardly as a shepherd who abandoned his flock. The last two verses of this sonnet repeat the end of Antonio’s sonnet: ‘And he betrayed everyone who hoped in him, / Making [our] Italy a slave for money!’

Of the surviving poems the most vehement invective against Charles IV is the canzone by the renowned Trecento poet Fazio degli Uberti (1301–67, born in Pisa, but active in Milan and Verona) ‘Di quel possi tu ber che bevve Crasso’, in which Italy speaks to the Emperor in an extremely irate tone: ‘Know that I am Italy who speaks to you, ignominious Carl of Luxemburg’ (vv. 16–17: ‘Sappi ch’i’ son Italia che ti parlo, / Di Lusimburgo ignominioso Carlo’). She wishes on Charles the cruellest tortures and the most horrible death for his betrayal of her hope for a better life (vv. 9–10: ‘E se non bastan queste / Tante bestemmie e tanta ria ventura!’). Instead of taking care of Italy, Charles took all the money he collected there back to his Bohemia (vv. 32–3: ‘di quello fai le spese / C’hai tolto qui e ne porti in Boemme’). In the last strophe of the canzone, the poet appeals to Jupiter, asking him why he did not take away from Charles IV’s hands, and from the hands of all the other avid German compatriots, his sacred symbol of the eagle, now decisively mocked by them (vv. 69, 77–80: ‘Tu dunque, Giove, perché ’l santo uccello . . . / Da questo Carlo quarto / Imperador non togli e dalle mani / Degli altri lurchi moderni Germani, / Che d’aquila un allocco n’hanno fatto?’ – lit. ‘the modern Germans who have made an owl out of the eagle’). Fazio’s curses for a terrible death recall many ancient heroes who ended their life miserably. For example, the opening line of the canzone, ‘From this [gold] may you drink like Crassus drank’, hints at the story of Marcus Licinius Crassus, a Roman general and the wealthiest man in Ancient Rome, who was killed in a battle against the Parthian Empire in 53 bc. His head was brought to the Parthian king Orodes II, who commanded that molten gold be poured into his mouth.Footnote 93

This verse, ‘Di quel possi tu ber che bevve Crasso’, was quoted by Sacchetti in his later poem ‘Canzone distesa che Franco Sacchetti fece quando papa Urbano V e Carlo di Lucimborgo passarono di concordia in Toscana, faccendo guerra a Firenze, anno MCCCLXVIII’ (Long canzone made by Franco Sacchetti, when Pope Urban V and Charles of Luxemburg passed together through Tuscany, making war against Florence, in 1368), written during Charles IV’s last visit to Italy in 1368–9. Tiredness, deep disappointment and lack of any enthusiasm run throughout this long poem. The traditional comparison of Charles IV with his homonym Charles the Great is not in his favour: ‘Your name should make you think many times about the great Charlemagne, but you do not care to procure for yourself the title [the Great] that he had’ (vv. 127–30: ‘Il nome tuo dovria molte fiate, / farti pensar qual fu il buon Carlo Magno: / tu non te ne dài lagno / d’avere il sopranome il qual ebbe egli’). Sacchetti records other two venerable Charleses and asks why in the fourth Charles only avidness is recognisable (vv. 136 and 138: ‘O quarto da costor, / . . . Perché avarizia in te si mostra e serba?’). The poet continues that Charles’s behaviour makes the people to curse him on any occasion, and he hears that they constantly repeat: ‘From this [gold] may you drink like Crassus drank’ (vv. 149–50: ‘e tua maniera / maladir sento, e dire ad ogni passo: / – Di quel possi tu ber che bevve Crasso!’). This quotation shows that Fazio degli Uberti’s canzone was well known and remained current even after the poet’s death in 1367.

In this short survey a large geographic area of reactions to Charles’s visit is seen. The range of emotions, however, remains more or less the same in all poets: from enthusiastic hopes to deep disappointment and frustration.

The Best of the Florentine Scepticisms in Donato’s Sovran Uccello

In Florence, as we have already seen in Villani’s chronicle and in Sacchetti’s poems, the attitude to Charles IV fluctuated from rather sceptical to openly negative from the very beginning of his Italian campaign. A strange judicial case of Matteo Villani is very telling in this regard. As Gene Brucker notes, at the beginning of 1362 Matteo ‘was accused as a suspected Ghibelline and thereby became ineligible to hold public office’, according to the Communal provision of 1347, which ‘prohibited any Ghibelline from holding communal office’.Footnote 94 Matteo decided to defend himself and brought a number of witnesses who succeeded in proving his innocence, attesting him to be a true Guelf. However, Matteo’s rival, Simone da Castiglionchio, insisted in his persecution and the next year, in April 1363 (some months before his death), Matteo Villani was definitely proclaimed as a Ghibelline with all the attendant consequences.

Brucker wonders ‘how can these persistent attempts to tar Matteo Villani with the brush of Ghibellinism be explained’, since Matteo did not occupy any significant position in the Florentine Commune. The only explanation for this hostility, in Brucker’s opinion, ‘lies apparently in the one achievement to which he owed his reputation: his chronicle’.Footnote 95 He was indeed very critical towards the rectors and other important functionaries of the Commune and their activity, failing to be honest: ‘he [Matteo] regarded them as vulgar parvenus, who, intent upon their personal advantage, were totally lacking in the ability and civic spirit necessary to govern a republic’.Footnote 96 In all probability, this was the true reason for the persecution, but Matteo’s writings could well have given a good excuse to the Commune to charge him with the crime of Ghibellinism: it was enough to express some empathy for the Emperor and to be polite in criticisms against him. Given this background, it would be difficult to imagine a truly positive and apologetic attitude towards the Holy Roman Emperor that could have intentionally been demonstrated by a Florentine.

If the Florentine composer Donato da Firenze indeed had in mind Charles IV while composing his madrigal Sovran uccello sei fra tutti gli altri, he has demonstrated this specific Florentine scepticism to the Emperor or rather to the very institution of the Holy Roman Empire.

We know little about Donato, only that he was a Benedictine monk in Florence. It is to be regretted that ‘very little information can be gleaned from the texts of Donato’s works, which are almost all madrigals’.Footnote 97 Almost a half of Donato’s surviving musical settings (eight of eighteen) are written to the texts of other poets: Franco Sacchetti, Niccolò Soldanieri, Antonio degli Alberti and Arrigo Belondi. All these attributions, however, are transmitted in literary sources only. Two madrigals by Sacchetti set to music by Donato fall in the period between 1358 and 1363. Their music has not survived, while the poetic texts with the inscription ‘magister Donatus presbiter de Cascia sonum dedit’ are transmitted in Sacchetti’s autograph codex Ashburnham 574 (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence). Scholars have extended Donato’s activity as a composer up to 1378 by linking his madrigal Dal cielo scese with the wedding of Samaritana da Polenta and Antonio della Scala in this year.Footnote 98

The two-voice madrigal Sovran uccello appears in three musical manuscripts – Codex Squarcialupi (Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Palatino 87, fols. 75v–76), Panciatichiano 26 (Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, fols. 82v–83) and San Lorenzo 2211 (Florence, Archivio Capitolare, fols. 53v–54). Interestingly, its text does not appear in any of the purely literary manuscripts known, recently investigated by Lauren Jennings.Footnote 99 It does not necessarily mean that this text could have not been written by some Florentine poet including those Donato preferred, but it makes it more probable that the words were Donato’s own. Although there is no mention of Charles IV by name, the allusion to the Emperor is obvious:

The second strophe refers unmistakably to the Emperor’s blazon (‘la tua figura’ – ‘your image’): an eagle with imperial crown and open wings, just as painted in Giovanni Sercambi’s chronicle (Figure 6; detail of Figure 5).

Figure 6 The imperial eagle in Giovanni Sercambi, Le croniche, fol. 53r (detail of Figure 5). Reproduced with the permission of the Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo; further reproduction prohibited

The sceptical tone of this madrigal is very noticeable: of course, this eagle makes an impression on everyone with its magnificence and splendour, but we, the knowledgeable ones, will stand aside and see what it is actually able to do. As linked to Charles IV, this text could well have been written before it became clear that the Emperor had no intention to remain in Italy after his Roman coronation. Indeed, judging by the words of the ritornello, the evil had not yet happened and some kind of hope was still tangible: let’s see. The poems examined earlier show that after Charles’s departure the only feelings that inspired the Italian poets to express their thoughts about the Emperor and the Holy Roman Empire were rage and indignation.

Evidently, the author of the text, be he Donato himself or someone else from his close circle, expresses his personal visual experience of the Emperor’s coat of arms – the eagle with open wings. Knowing that neither Emperor, nor Empress, nor any imperial emissary had ever entered the city officially (the latter only in complete secrecy by night, according to Matteo Villani), we may assume that the only possibility of such an intensive exposure to the imperial symbol of eagle might have happened during the lodging of a part of the Empress’s retinue in Florence in March 1355, as reported in Matteo Villani’s chronicle. It is possible thus to assume that the madrigal Sovran uccello is one more reminiscence, together with Sacchetti’s sonnet ‘Firenze bella’, of this event, but it is exceptional, since it was set to music.

Donato’s music for this madrigal is typical of Trecento composers of the so-called second generation. It traditionally has a more elaborated upper voice and a slower tenor; long melismas fall on the first and the penultimate syllables of the line. As noted by Kurt von Fischer, it ‘is indebted stylistically to Jacopo da Bologna, notably in the transitional phrases between lines of madrigal verse, these being usually untexted and monophonic (though some are two-voiced and more modern in style), and in sporadic points of imitation’.Footnote 102 These characteristics hold true for the madrigal Sovran uccello, where the two-voice transitional passages in imitation and hocket technique occur three times (bb. 29–34, 59–62 of the tercets and 91 of the ritornello) (see Example 1).

Example 1 Donato da Firenze, Sovran uccello sei. After Italian Secular Music, 2: Vincenzo da Rimini, Rosso de Chollegrana, Donato da Firenze, Gherardello da Firenze, Lorenzo da Firenze, ed. W. T. Marrocco ( Monaco, 1971), pp. 66–8

Elsewhere I have noted a particular characteristic of Donato’s compositional style, which appears in nine of his fourteen madrigals, namely the change from binary to ternary metre not at the seam of the madrigal’s sections (from the tercet to the ritornello), but at the beginning of the third line of the tercet or at the beginning of the penultimate-syllable melisma of the third line, and the ternary metre continues in the ritornello.Footnote 103 The madrigal Sovran uccello is one of these nine madrigals.

Unlike many other madrigals by Donato, like I fu’ già bianc’ucciel and Un bel girfalco, with longer or shorter sections of non-simultaneous pronunciation of the poetic text in both voices, the text of the madrigal Sovran uccello has complete synchronisation. The imitations, not being linked with the words, are purely musical. The most interesting and quite perceptible aurally is the descending motif a–(g)–g–f–f–e–d, first appearing in bars 31–4 in the tenor of the transitional phrase between the first and the second line, then repeated in the upper voice on the words of the second line, ‘O, imperadrice’ (bb. 43–5) and after that immediately in the tenor on the words ‘Quando vol’a cieli’ (bb. 47–9). The musical texture abounds with hockets in the melismatic sections and in the transitional motifs.

The vertical arrangement of the voices also testifies in favour of the early dating of this composition. Using the criterion of the correlation of the number of parallel perfect intervals of the same species in a composition with its chronology, first proposed by Dorothea BaumannFootnote 104 and recently developed by Maria Caraci Vela,Footnote 105 a high number of such intervals, ten in total (eight consecutive fifths in bb. 10–11, 25–6, 39–41, 54–5, 69, 73, 95–6 and two consecutive octaves in bb. 51–2 and 68) suggests that this madrigal was written not later than the early 1360s. Thus, the proposed date of composition between March and June of 1355 agrees well with this stylistic peculiarity.

The close examination of the madrigals Aquil’altera and Sovran uccello in the larger historical and cultural background brings us to the following conclusions.

Regarding Jacopo da Bologna’s madrigal, one may now see how an author can form a concept using allegory in manifold ways. Certainly, the eagle, with its association with heraldry, evokes first of all an idea of imperial power and imperial coats of arms. Thus, Charles IV has been chosen as a ‘default option’. However, investigation of the wider historico-cultural context of his Milanese coronation in 1355 has substantially reduced the plausibility of his candidature for the role of protagonist of the madrigal Aquil’altera, especially when viewed in the light of the Visconti attitude to him.

On the other hand, some features related to the Visconti family, namely the fact that the father and three sons had the names of all four evangelists, and the intellectual prominence of the Milanese governor Archbishop Giovanni Visconti (during 1349–54), suggests a new option, namely to interpret the image of the eagle as a symbol of the evangelist John. Cecco d’Ascoli’s and Petrarch’s readings of the eagle’s flight as a symbol of the power of intellect and knowledge actually go back to Homilies on the Prologue of the Gospel of John by Eriugena. The textual and conceptual affinity of Jacopo’s Aquil’altera with some passages from Eriugena’s Homilies is evident, so that the candidature of Giovanni Visconti as the addressee of this madrigal appears now as the most likely.

Donato’s Sovran uccello, in turn, perfectly accords with the atmosphere of the Florentine intolerance of the Empire and its representatives. It is indeed a purely political madrigal undoubtedly associated with Charles IV’s expedition in Italy in 1355, but, unlike many other Trecento compositions, it is not laudatory but it appears to be a kind of a political pamphlet.

Appendix 1

Matteo Villani’s Description of how the Emperor Went to Monza for the Iron Crown

Cronica, Book 4, chapter 39, ‘Come lo ’mperadore andò a Moncia per la corona del ferro’ Footnote 1

Appendix 2

Jacopo da Bologna, Aquil’altera/Creatura gentil/Uccel di Dio