Introduction

In 2006, in the final chapter of his study of the Zhushu jinian 竹書紀年 (Bamboo Annals) and other ancient Chinese historical writings, Edward Shaughnessy suggested that it was only a matter of time before some new textual discovery transformed our understanding of ancient Chinese history: “We may see the day when the Bamboo Annals or a text something like it, is rediscovered, not in a tomb, but in the libraries of hardworking editors.”Footnote 1 As it has transpired, he was quite correct, though this rediscovery has not come from reconstructing the Zhushu jinian text (work which is still ongoing), but from the donation by an anonymous alumnus of a major collection of bamboo texts to Qinghua University 清華大學 in 2008. The provenance of the Qinghua group of texts (comprising more than 2,300 individual bamboo strips) is not known, but they are thought to derive from a tomb robbery in either Hubei or Hunan Province. One of these texts is the Xinian 繫年, or Annalistic History.Footnote 2 The Xinian covers events from the history of the Western Zhou dynasty (1045–771 b.c.e.), through the Spring and Autumn Period (771–475 b.c.e.) and into the Warring States era (475–221 b.c.e.); the most recent events recorded in this text concern the reign of King Dao 楚悼王 (r. 400–378 b.c.e.).Footnote 3 This is compatible with the date obtained by C14 analysis of one of the bamboo strips: 305 b.c.e. +/− 30 years.Footnote 4 Although much of the material found in the Xinian records the history of the Zhou confederacy, there is a significant focus on the kingdom of Chu. This agrees with the supposed location of the tomb from which this text was derived, within the borders of this ancient southern kingdom.

The Xinian consists of twenty-three individual pericopes written on 138 bamboo strips, each ranging from 44.6–45 cm in length. For the convenience of readers of the original manuscript, the number of each strip was written on the back. However, there are two mistakes in the count: number fifty-two is duplicated but number eighty-eight is missing; furthermore the final strip of the text, number 138, is not numbered. Most scholars have simply followed the ordering of the text indicated by the Warring States era numbering; however, Wang Liancheng 王連成 has suggested that this represents a post facto addition to the text and is not necessarily correct.Footnote 5 In particular, he notes that pericopes one, three and four begin with accounts of the events at the time of the founding of the Zhou dynasty, while pericope two describes the collapse of the Western Zhou dynasty in 771 b.c.e. Therefore, he suggests that the original order was disturbed, and the mistake has been preserved in the modern transcription thanks to the ancient numbering imposed on the text.

Classifying the Xinian

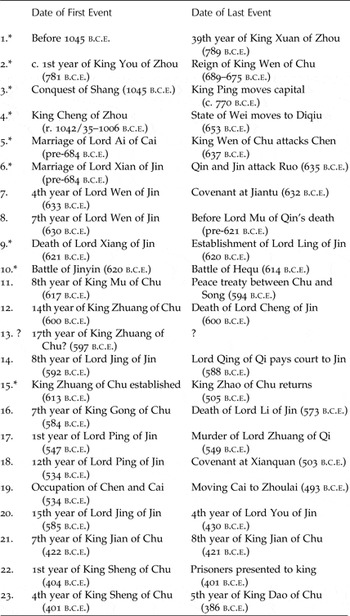

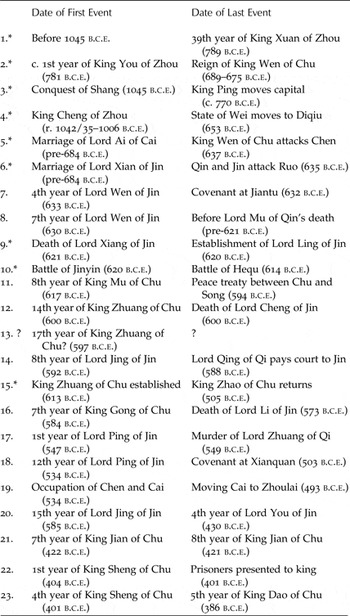

Unlike the Chunqiu 春秋 (Spring and Autumn Annals) and its commentaries, or indeed the Zhushu jinian, the Xinian is not an annalistic history in the strict sense of the words. As has been pointed out by a number of scholars, the name chosen for this text is a misnomer: each entry does not start with a date, and the present ordering of the text is not completely chronological.Footnote 6 Although some scholars have persisted in attempting to classify the Xinian as an annalistic history, this is rendered extremely difficult by the range of dates covered by the text.Footnote 7 Within each individual pericope, events that took place over the course of many decades—or even centuries—are discussed together, with considerable chronological overlap (see Table 1):

Table 1. Dates of events recorded in the Xinian*

Note: * The pericope numbers marked with an asterisk are those which begin without an explicit indication of dating; in these instances a date has been assessed from internal evidence.

Although it has frequently been stated that the Xinian is a Chu historical text, much of the focus of the narrative is upon the changing and developing relationship between Chu and Jin.Footnote 8 The internal evidence of origin seems to be extremely problematic, given that some events are dated according to the Jin calendar, and some according to the Chu calendar. This dual focus has resulted in scholars suggesting that the Xinian may be related to the Guoyu 國語 (Discourses of the States) discovered with the Zhushu jinian—a text which has now been lost.Footnote 9 This text is described in the Jinshu 晉書 (History of the Jin dynasty): “A Guoyu in three chapters, describing the history of Chu and Jin” (國語三篇, 言楚晉事).Footnote 10 It is certainly true that the second half of the text concentrates on the history of these two states, but it is premature to associate the Xinian with an earlier textual discovery about which so very little is known. Alternatively, a number of scholars researching the Xinian have been drawn to the idea that this text represents a précis produced within the Chu court, and just such a text is described in the Shiji: “Duo Jiao was the tutor to King Wei of Chu, and since the king was not able to comprehend the entire Chunqiu [Zuozhuan], he selected the most important events, forty pericopes in all, thus forming the Duoshi wei (Highlights of Master Duo)” (鐸椒為楚威王傅, 為王不能盡觀春秋, 采取成敗, 卒四十章, 為鐸氏微).Footnote 11 For some scholars, in spite of the different lengths recorded for this text, the Xinian is—if not identical to the Duoshi wei—then at the very least closely related to it.Footnote 12 The wish to identify recently discovered bamboo texts with previously recorded but lost ancient writings is extremely strong, and the Xinian is not the only historical text to have been linked with the Duoshi wei. The Zhengzi jia sang 鄭子家喪 (The Funeral of Zijia of Zheng), a text recounting a single historical story concerning conflict between Jin and Chu, has also been identified as deriving from the Duoshi wei.Footnote 13 Likewise, it has been suggested that the badly damaged historical text excavated from the late Warring States era tomb at Cili 慈利 in Hunan Province in 1987 is related to the Duoshi wei.Footnote 14 The difficulties of reconciling these attributions rests in the very brief description given of this book in Han dynasty texts, coupled with the fact that number of fascicles and other such bibliographical structuring remained fluid well into the imperial era. In the case of the Xinian, a close connection with the Duoshi wei is very unlikely, since it is not a précis of any known text. However, this suggested classification does point to one of the major features of the text. The Xinian is a very condensed source of information about the history of the Zhou dynasty, focusing on events that led to significant changes in the balance of power.

Rather than attempt a classification, some scholars have tried to group the contents by theme. So far, all of these studies have agreed to divide the contents of the Xinian into three main groups of material. Li Xueqin 李學勤 has proposed a chronological classification: pericopes one to four concern the Western Zhou dynasty, recording events up until the capital moved to the east in the time of King Ping (r. 770–720 b.c.e.); pericopes five to nineteen describe events during the Spring and Autumn period; pericopes twenty to twenty-three record Warring States era history.Footnote 15 Alternatively, Xu Zhaochang 許兆昌 and Qi Dandan 齊丹丹 have suggested that pericope one represents an overview of the entire history of the Western Zhou dynasty; pericopes two to five give a simple account of the history of some of the more important states of the Zhou confederacy; and pericopes six to twenty-three describe important events in the history of the Eastern Zhou dynasty, with particular reference to the interaction between Chu and Jin.Footnote 16 Meanwhile Yuri Pines has suggested a tripartite division, based upon the presumed origin of the textual material, with pericopes one to four forming a “Zhou” section; pericopes six to ten, fourteen, seventeen, and twenty forming a “Jin” section; and periscopes five, eleven to thirteen, fifteen to sixteen, nineteen, and twenty to twenty-three forming a “Chu” section. In addition, pericope eighteen is described as a “Jin-Chu” section.Footnote 17

The form of the characters found in the Xinian is consistent with a provenance from the kingdom of Chu; however, the same certainty does not pertain for the contents. Indeed, the vocabulary in use in the Xinian (in particular some of the grammatical particles found in this text) are not common in Warring States era writings from Chu. This has led to Chen Minzhen 陳民鎮 raising the possibility that the text originally derived—either in whole or in part—from elsewhere and the Qinghua manuscript was simply a copy produced in Chu.Footnote 18 I would like to suggest that the Zhushu jinian here forms an instructive parallel. Scholars working on this text have accepted that the Zhushu jinian is derived from two source texts: one an annalistic history of the early dynasties of Chinese history and the second an annalistic history of the state of Jin, and subsequently the state of Wei.Footnote 19 In spite of the manifest problems with attempting to classify the Xinian, and the difficulties caused by the fact that this text uses two different calendars, there seems to have been considerable reluctance to accept that it could be a compilation.Footnote 20 Here, I suggest that the Xinian manuscript should be considered as the uniform product of a single hand, but where the contents derive from five different source texts. One is a collection of accounts concerning the late Western Zhou dynasty and the circumstances surrounding the founding of the Eastern Zhou dynasty (A: pericopes 1–4). The second source text is a selection of scandalous stories which have a particular importance for the history of the kingdom of Chu (B: pericopes 5 and 15). This text can be distinguished from Source Text D, which also focuses on the history of Chu, by its lack of explicit dates. There is also some overlap in material—the beginning of pericope twenty repeats information from the end of pericope fifteen, suggesting again that the Xinian was compiled from a variety of sources. Then there is a group of closely-related stories concerning the history of the state of Jin during the time of Lord Wen of Jin 晉文公 (r. 636–628 b.c.e.) and his successors (C: pericopes 6–10). This focuses on a very narrow time-period of just over twenty years (636–614 b.c.e.), though the text does not always make explicit reference to dating. In this section, although the narrative is divided into different pericopes, the account flows smoothly from one to the next. There is a source text focusing on the history of the kingdom of Chu (D: pericopes 11–13, 16, 19, 21–23); and a source text focusing on the history of the state of Jin (E: pericopes 14, 17–18, 20). Both D and E are characterized by careful attention to dating, furthermore E can be distinguished from C by the unconnected narrative and the much longer time-span under consideration: nearly two hundred years. This internal arrangement is significant not only for understanding how the text was composed, but also for demonstrating its authenticity. It is extremely unlikely that a forger would produce so complex an arrangement of material.

The transcription of the text given below follows that published in 2011 in the Qinghua daxue cang Zhanguo zhujian 清華大學藏戰國竹簡 (Warring States era Bamboo Books in the Collection of Qinghua University), with loan characters indicated by [graph] and additions indicated by 【graph】. Duplicate characters and contractions will be indicated as they are in the original manuscript, with the mark = followed by the relevant additional character in parentheses. In the case of amendments made by other scholars, the attribution will be given in a footnote. In each case the number on the back of the strip will be indicated first in subscript, followed by the actual number of the strip determined by the scholars arranging the text for publication (1/1 and so on). Most pericopes have the punctuation mark ㄴ at the end. The exceptions are the damaged strip at the end of story thirteen, and stories fifteen and twenty-two, which simply lack this conventional mark. For the purposes of this discussion, the text has been regrouped according to the source text that it is derived from, rather than preserving the original order.

Annotated Translation

Source Text A

PERICOPE ONE

1/1 昔周武王監觀商王之不龏[恭]

![]() =[上帝], 禋祀不

=[上帝], 禋祀不

![]() [寅]. 乃乍[作]帝𢼎[籍]以

[寅]. 乃乍[作]帝𢼎[籍]以

![]() [登]祀

[登]祀

![]() =[上帝]天神: 名之曰 2/2 千

=[上帝]天神: 名之曰 2/2 千

![]() [畝]. 以克反商邑, 尃[敷]政天下.

[畝]. 以克反商邑, 尃[敷]政天下.

![]() =[至于]

=[至于]

![]() =王=[厲王, 厲王]大

=王=[厲王, 厲王]大

![]() [虐]于周卿

[虐]于周卿

![]() [士]者[諸]正萬民, 弗刃[忍]于氒[厥]心, 3/3 乃歸

[士]者[諸]正萬民, 弗刃[忍]于氒[厥]心, 3/3 乃歸

![]() [厲]王于

[厲]王于

![]() [彘]. 龍[共]白[伯]和立十又四年,

[彘]. 龍[共]白[伯]和立十又四年,

![]() [厲]王生洹=王=(宣王. 宣王)即立[位], 龏[共]白[伯]和歸于宋[宗]. 洹[宣] 4/4 王乃

[厲]王生洹=王=(宣王. 宣王)即立[位], 龏[共]白[伯]和歸于宋[宗]. 洹[宣] 4/4 王乃

![]() [始]弃[棄]帝

[始]弃[棄]帝

![]() [籍]弗畋[田]. 立 丗[三十]又九年, 戎乃大敗周𠂤[師]于千

[籍]弗畋[田]. 立 丗[三十]又九年, 戎乃大敗周𠂤[師]于千

![]() [畝].ㄴ

[畝].ㄴ

1/1 In the past, King Wu of Zhou observed that the Shang king did not respect God on High,Footnote 21 and that sacrifices were not performed reverently.Footnote 22 Therefore, he created divine revenue [fields] in order to present sacrifice to God on High and the Spirit of Heaven: the name of this place was 2/2 Qianmu.Footnote 23 Thus he conquered the Shang, spreading good government across the entire world. In the time of King Li (r. 878–841 b.c.e.), King Li behaved with great cruelty to the ministers, elders, and the common people of Zhou, so that they could no longer bear it in their hearts, 3/3 therefore they exiled King Li to Che (Zhi).Footnote 24 In the fourteenth year of the reign of He, the earl of Gong [865 b.c.e.], King Li had a son named King Xuan (r. 827–782 b.c.e.). When King Xuan came to the throne, He, earl of Gong, went home to live in Song (Zong).Footnote 25 King 4/4 Xuan was the first to abandon the divine revenue fields and not to cultivate them.Footnote 26 He was on the throne for thirty-nine years and then the Rong nomadic people inflicted a serious defeat on the Zhou army at Qianmu.Footnote 27

PERICOPE TWO

5/5 周幽王取妻于西

![]() [申], 生坪[平]王=[王. 王] 或[又]

[申], 生坪[平]王=[王. 王] 或[又]

![]() [取]孚[褒]人之女, 是孚[褒]

[取]孚[褒]人之女, 是孚[褒]

![]() [姒], 生白[伯]盤. 孚[褒]

[姒], 生白[伯]盤. 孚[褒]

![]() [姒]辟[嬖]于王=[王, 王] 6/6 與白[伯]盤, 迖[逐]坪[平]=王=[平王, 平王] 走西

[姒]辟[嬖]于王=[王, 王] 6/6 與白[伯]盤, 迖[逐]坪[平]=王=[平王, 平王] 走西

![]() [申]. 幽王起𠂤[師]回[圍]坪[平]王于西

[申]. 幽王起𠂤[師]回[圍]坪[平]王于西

![]() [申]=[申, 申]人弗

[申]=[申, 申]人弗

![]() [畀]. 曾[繒]人乃降西戎以 7/7 攻幽=王=[幽王. 幽王]及白[伯]盤乃滅, 周乃亡. 邦君者[諸]正乃立幽王之弟

[畀]. 曾[繒]人乃降西戎以 7/7 攻幽=王=[幽王. 幽王]及白[伯]盤乃滅, 周乃亡. 邦君者[諸]正乃立幽王之弟

![]() [余]臣于

[余]臣于

![]() [虢], 是㽯[攜]惠王. 8/8 立廿=[二十]又一年, 晉文侯

[虢], 是㽯[攜]惠王. 8/8 立廿=[二十]又一年, 晉文侯

![]() [仇]乃殺惠王于

[仇]乃殺惠王于

![]() [虢]. 周亡王九年, 邦君者[諸]侯

[虢]. 周亡王九年, 邦君者[諸]侯

![]() [焉]

[焉]

![]() [始]不朝于周. 9/9 晉文侯乃逆坪[平]王于少鄂, 立之于京𠂤[師]. 三年乃東

[始]不朝于周. 9/9 晉文侯乃逆坪[平]王于少鄂, 立之于京𠂤[師]. 三年乃東

![]() [徙], 止于成周. 晉人

[徙], 止于成周. 晉人

![]() [焉]

[焉]

![]() [始]啟 10/10 于京𠂤[師]. 奠[鄭]武公亦政[正]東方之者[諸]侯. 武 公即殜[世],

[始]啟 10/10 于京𠂤[師]. 奠[鄭]武公亦政[正]東方之者[諸]侯. 武 公即殜[世],

![]() [莊]公即立[位];

[莊]公即立[位];

![]() [莊]公即殜[世], 卲[昭]公即立 [位]. 11/11 其夫=[大夫]高之巨[渠]爾[彌]殺卲[昭]公而立其弟子釁[眉]壽. 齊襄公會者[諸] 侯于首

[莊]公即殜[世], 卲[昭]公即立 [位]. 11/11 其夫=[大夫]高之巨[渠]爾[彌]殺卲[昭]公而立其弟子釁[眉]壽. 齊襄公會者[諸] 侯于首

![]() [止], 殺子 12/12 釁[眉]壽, 車

[止], 殺子 12/12 釁[眉]壽, 車

![]() [轘]高之巨[渠]爾[彌], 改立

[轘]高之巨[渠]爾[彌], 改立

![]() [厲]公. 奠[鄭]以

[厲]公. 奠[鄭]以

![]() [始]政[正]. 楚文王以啟于灘[漢]

[始]政[正]. 楚文王以啟于灘[漢]

![]() [陽].ㄴ

[陽].ㄴ

5/5 King You of Zhou (r. 781–771 b.c.e.) took a wife from Western Shen, and she gave birth to King Ping.Footnote 28 The king also took a woman from the people of Fu (Bao),Footnote 29 this was Lady Fu Si (Bao Si), and she gave birth to Bopan.Footnote 30 Lady Fu Si was favoured by the king. His Majesty 6/6 loved Bopan, and thus forced King Ping into exile: King Ping fled to Western Shen.Footnote 31 King You raised an army and laid siege to King Ping at Western Shen, but the people of Shen were not afraid. The people of Zeng then joined with the Western Rong in order 7/7 to attack King You; King You and Bopan were killed and the Zhou dynasty was destroyed. The lords of the various states and the elders then established King You's younger brother, Yuchen, in Guo, and he became King Hui of Xie (r. 770–750 b.c.e.). 8/8 He was established for twenty-one years, after which Chou, Marquis Wen of Jin (r. 780–746 b.c.e.), killed King Hui in Guo. Zhou was without a king for nine years (749–741 b.c.e.), so the lords of the various states began not to pay court to Zhou. 9/9 Marquis Wen of Jin met King Ping at Shao'e and had him take the throne in the capital.Footnote 32 In the third year (738 b.c.e.), he moved the capital east, taking up residence in Chengzhou. The people of Jin then began to open up land 10/10 around the capital. Lord Wu of Zheng (r. 771–744 b.c.e.) was the leader of the lords in the eastern regions. When Lord Wu passed away, Lord Zhuang (r. 743–701 b.c.e.) was established; when Lord Zhuang passed away, Lord Zhao (r. 700–695 b.c.e.) was established.Footnote 33 11/11 His Grandee Gao Zhi Juer (Gao Qumi) killed Lord Zhao and established his younger brother Xinshou (Meishou).Footnote 34 Lord Xiang of Qi (r. 698–686 b.c.e.) met the other lords at Shouzhi, killing the unratified lord, 12/12 Xinshou, and rending Gao Zhi Juer apart with chariots. He established Lord Li instead (r. 700–673 b.c.e.) and the state of Zheng began from this point on to be well-governed.Footnote 35 King Wen of Chu then opened up land at Tanyang (Hanyang).Footnote 36

PERICOPE THREE

13/13 周武王既克

![]() [殷], 乃執[設]三監于殷. 武王陟, 商邑興反, 殺三監而立

[殷], 乃執[設]三監于殷. 武王陟, 商邑興反, 殺三監而立

![]() 子耿. 成 14/14 王屎[纉]伐商邑, 殺

子耿. 成 14/14 王屎[纉]伐商邑, 殺

![]() 子耿.Footnote

37

飛𤯍[廉]東逃于商盍[蓋]氏, 成王 伐商盍[蓋], 殺飛𤯍[廉], 西

子耿.Footnote

37

飛𤯍[廉]東逃于商盍[蓋]氏, 成王 伐商盍[蓋], 殺飛𤯍[廉], 西

![]() [遷]商 15/15 盍[蓋]之民于邾

[遷]商 15/15 盍[蓋]之民于邾

![]() [吾], 以御奴

[吾], 以御奴

![]() 之戎: 是秦先=[先人], 殜[世]乍[作]周

之戎: 是秦先=[先人], 殜[世]乍[作]周

![]() [扞]. 周室即[既]

[扞]. 周室即[既]

![]() [卑]坪 [平]王東遷, 止于成 16/16 周. 秦中[仲]

[卑]坪 [平]王東遷, 止于成 16/16 周. 秦中[仲]

![]() [焉] 東居周地以

[焉] 東居周地以

![]() [守] 周之

[守] 周之

![]() [墳]

[墳]

![]() [墓]. 秦以

[墓]. 秦以

![]() [始]大.ㄴ

[始]大.ㄴ

13/13 When King Wu of Zhou defeated the Yin, he established the Three Guardians in Yin. When King Wu died, the Shang city rose in rebellion, killing the Three Guardians and establishing Geng, Viscount of Lu.Footnote 38 King 14/14 Cheng repeatedly attacked the Shang city, killing Geng, Viscount of Lu.Footnote 39 Feilian fled east to the Shanggai clan, whereupon King Cheng attacked Shanggai and killed Feilian.Footnote 40 He moved the people of Shang 15/15 gai west to Zhuwu, in order that they might control the Nuzha Rong.Footnote 41 These were the ancestors of the Qin.Footnote 42 From one generation to the next they were the protectors of Zhou.Footnote 43 When the Zhou royal house declined, King Ping moved east and took up residence in Cheng 16/16 zhou. At this point Qin Zhong moved east into the lands of Zhou, in order to guard the tombs of the Zhou [ruling house].Footnote 44 Qin then began to become an important [state].

PERICOPE FOUR

17/17 周成王, 周公既

![]() [遷]殷民于洛邑, 乃𡶫[追]念

[遷]殷民于洛邑, 乃𡶫[追]念

![]() [夏]商之亡由, 方[旁]執[設]出宗子, 以乍[作]周厚 18/18

[夏]商之亡由, 方[旁]執[設]出宗子, 以乍[作]周厚 18/18

![]() [屏], 乃先建

[屏], 乃先建

![]() [衛]弔[叔]

[衛]弔[叔]

![]() [封]于庚[康]丘以侯殷之

[封]于庚[康]丘以侯殷之

![]() [餘]民.

[餘]民.

![]() [衛]人自庚[康]丘

[衛]人自庚[康]丘

![]() [遷]于

[遷]于

![]() [淇]

[淇]

![]() [衛]. 周惠王立十 19/19 又七年赤𨞩[翟]王峁

[衛]. 周惠王立十 19/19 又七年赤𨞩[翟]王峁

![]() 𨑓[起] 𡶫[師]伐

𨑓[起] 𡶫[師]伐

![]() [衛], 大敗

[衛], 大敗

![]() [衛]𡶫[師]於睘. 幽侯滅

[衛]𡶫[師]於睘. 幽侯滅

![]() [焉], 翟述[遂]居

[焉], 翟述[遂]居

![]() =[衛. 衛]人乃東 20/20 涉河䙴[遷]于曹

=[衛. 衛]人乃東 20/20 涉河䙴[遷]于曹

![]() [焉]立悳[戴]公申. 公子啟方奔齊.

[焉]立悳[戴]公申. 公子啟方奔齊.

![]() [戴]公

[戴]公

![]() [卒], 齊𧻚[桓]公會 者[諸]侯以成[城]楚丘, □ 21/21 公子啟方

[卒], 齊𧻚[桓]公會 者[諸]侯以成[城]楚丘, □ 21/21 公子啟方

![]() [焉]是文=公=[文公. 文公]即殜[世], 成公即立[位]. 翟人或[又]涉河伐衛于楚丘, 衛人自楚丘 22/22

[焉]是文=公=[文公. 文公]即殜[世], 成公即立[位]. 翟人或[又]涉河伐衛于楚丘, 衛人自楚丘 22/22

![]() [遷]于帝丘.ㄴ

[遷]于帝丘.ㄴ

17/17 When King Cheng of Zhou and the Duke of Zhou moved the Yin people to Luoyi, they remembered the reasons why the Xia and the Shang dynasties had collapsed.Footnote 45 Thus they established junior members of the ruling house [in fiefs] far and wide in order that they might act as a protective 18/18 screen for Zhou.Footnote 46 Thus they initially established Wei Diao Feng (Wei Shu Feng) at Gengqiu (Kangqiu), in order that he might rule over the remaining Yin people.Footnote 47 The men of Wei from Gengqiu moved to Qiwei. In the seventeenth 19/19 year [660 b.c.e.] of the reign of King Hui of Zhou (r. 676–652 b.c.e.), King Liuhu of the Red Di raised an army and attacked Wei.Footnote 48 He inflicted a terrible defeat on the Wei army at Qiong, and Marquis You (r. 668–660 b.c.e.) was killed by him.Footnote 49 The Di thereupon occupied Wei, and the people of Wei moved east and crossed 20/20 the Yellow River, travelling towards Cao. They established Shen, Lord Dai [of Wei] (r. 660–659 b.c.e.) as their new ruler, and the Honourable Qifang fled to Qi.Footnote 50 When Lord Dai passed away, Lord Huan of Qi (r. 685–643 b.c.e.) summoned all the regional lords with a view to fortifying Chuqiu, [one character illegible in the original text; from context this should be “establishing”] 21/21 the Honourable Qifang there: he became Lord Wen (r. 659–641 b.c.e.).Footnote 51 When Lord Wen passed away, Lord Cheng (r. 640–606 b.c.e.) was established. The Di people again crossed the Yellow River and attacked Wei at Chuqiu, so the Wei people had to 22/22 move from Chuqiu to Diqiu.

* * *

This group of stories focuses primarily on the reigns of four Zhou dynasty monarchs: Kings Li, Xuan, You and Ping. The first story concerns the regency of the earl of Gong; the Xinian confirms the account of these events given in the Zhushu jinian, which was the first textual discovery to alert scholars to a mistake in the Shiji.Footnote 52 The Shiji states that after King Li abandoned the capital in the wake of serious political upheavals: “The two prime ministers, the duke of Shao and the duke of Zhou, were in charge of the government, and they took the title: ‘United and Harmonious’” (Shaogong, Zhougong erxiang xingzheng, hao yue Gonghe 召公周公二相行政, 號曰共和): that is, Sima Qian had misunderstood the name “He of Gong” as an epithet.Footnote 53 The Xinian suggests that the eventual transfer of power from the earl of Gong to King Xuan was peaceful; this echoes the closely-related account given in the Lu Lianzi 魯連子, a text dated to the Warring States era which now survives only in a handful of quotations.Footnote 54

In the second story, the Xinian provides important clarification concerning one of the major scandals of the Zhou dynasty; the civil war which broke out when King You attempted to dispossess his Crown Prince. According to the Shiji, King You was killed and Lady Bao Si taken prisoner; the fate of their son, Prince Bofu, is not mentioned.Footnote 55 This raised the possibility that he survived the sack of the Zhou capital, a theory which was thoroughly explored by imperial era commentators on historical texts. Of particular interest to those scholars who wanted to trace the fate of Prince Bofu was the cryptic reference to the king of Xie preserved in the Zuozhuan: “The king of Xie was in violation of the statutes so the lords dismissed him” (Xiewang jian ming zhuhou ti zhi 携王奸命諸侯替之).Footnote 56 In the commentary by Du Yu (222–85), this king of Xie is specifically identified as Prince Bofu, and his lead was followed by many later imperial era scholars.Footnote 57 However, the Zhushu jinian provides a different account, which is more closely related to that found in the Xinian:

犬戎殺王子伯服, 執褒姒以歸. 申侯, 魯侯, 許男, 鄭子立宜臼于申; 虢公翰立王子余臣于攜.

The Quanrong killed Prince Bofu and captured Lady Bao Si, taking her away with them. The marquis of Shen, the marquis of Lu, the baron of Xu and the unratified lord of Zheng established Yijiu in Shen [as King Ping]. Lord Han of Guo established Prince Yuchen in Xie.Footnote 58

Again, the Zhushu jinian agrees with the Xinian that King Hui was killed by Lord Wen of Jin some twenty-one years later (750 b.c.e.).Footnote 59 This has been taken to mean that when King You died, the divisions between different factions in the ruling elite were so strong that the realm effectively split into two. King Hui of Xie, King You's younger brother, was established by the senior ministers and hereditary aristocracy of Zhou. At the same time, King Ping of Zhou was based elsewhere, and would likely have had the greatest difficulty in unifying the country again were it not for the fact that his cause was supported by Marquis Wen of Jin. To add to this impression of a dangerously divided country, a quotation from the Zhushu jinian given by Kong Yingda 孔穎達 (574–648)—not found in the transmitted text—states that King Ping was already crowned by his supporters before King You's death, suggesting that there was a succession of double monarchies in Zhou during this time.Footnote 60

An alternative theory for understanding the sequence of events at the time of the collapse of the Western Zhou dynasty has been proposed by Wang Hui 王暉.Footnote 61 In this reading of the Xinian, there was no double monarchy at all—on the death of King You, his younger brother was established as the ruler. When King Hui of Xie was murdered, a further nine years of chaos ensued, followed by the establishment of King Ping, who subsequently moved the capital of his kingdom to the east. The Xinian states that “there was no king of Zhou for nine years” (Zhou wang wang jiu nian 周亡王九年). Various other scholars have attempted to explain this statement: Wang Hongliang 王紅亮 has suggested that this refers back in time to the era immediately prior to the death of King You, when the monarch had alienated his lords.Footnote 62 Alternatively, it has been suggested that it refers to the time immediately after the civil war, when King Ping and King Hui were both on the throne; however, it would seem there was a plethora of kings rather than an absence at that point.Footnote 63 Wang Hui therefore proposes a strictly chronological reading of the Xinian: King You and Prince Bopan were killed—King Hui of Xie ruled for twenty-one years—there was a nine-year interregnum—King Ping came to the throne and three years later moved the capital to the east. This would mean that King Ping's reign was nearly thirty years shorter than previously thought, and that the chaos and upheavals of the three decades following the death of King You are likely to have been much more profound than suggested in later texts; the difficulties of this era have been elided within the historical tradition aimed at enhancing the legitimacy of Zhou rule in general, and that of King Ping in particular.Footnote 64 There is a very good reason why the chronology of the Xinian should be so different from that found in the transmitted tradition: subsequent generations had a considerable interest in minimizing the suggestion that King Ping and the marquis of Jin were regicides.Footnote 65 A text derived from outside the mainstream Zhou tradition would be more likely to record this fact than one produced under the auspices of the descendants of King Ping and his cohort.

The third story gives an account of the rebellions launched by remnants of the Shang regime against Zhou authority in the early years of the dynasty. In the Yizhou shu 逸周書 (Lost History of Zhou) it says: “King Wu conquered the Shang and then he established Prince Lufu, ordering him to take charge of the Shang sacrifices. He established Guan Shu in the east and he established Cai Shu and Huo Shu in Yin, ordering them to oversee the vassals of Yin” (武王克殷. 乃立王子禄父俾守殷祀. 建管叔于東; 建蔡叔, 霍叔于殷, 俾監殷臣).Footnote 66 This makes no specific reference to the Three Guardians (Sanjian 三監); however, the Han dynasty compilation entitled the Shangshu dazhuan 尚書大傳 (Greater Traditions of the Book of Documents) states: “Guan Shu and Cai Shu [were responsible for] overseeing Lufu … but Lufu and the Three Guardians rebelled” (管叔, 蔡叔, 監禄父 … 禄父及三監叛).Footnote 67 This seems to be the earliest recorded incidence within the transmitted tradition of this particular administrative title. However, the precise identity of the Three Guardians is unclear, and the Xinian does not assist by naming these important figures in early Western Zhou history. The majority of ancient texts mention Guan Shu and Cai Shu in tandem; a very small number also record Huo Shu, who was most likely the third of the Three Guardians.Footnote 68 However, by at least the time of the Han dynasty, these events had become confused: it is Wugeng, Guan Shu, and Cai Shu who are said to have risen in rebellion against the Zhou, only to be executed by the duke of Zhou in his capacity as regent.Footnote 69 The Xinian thus offers important clarification of the sequence of events. However, the identification of the Three Guardians as Guan Shu, Cai Shu, and possibly Huo Shu creates a serious problem, which has resulted in Lu Yihan 路懿菡 suggesting that this attribution is wrong.Footnote 70 As he notes, if the Three Guardians are identified specifically with Guan Shu and Cai Shu, then these two men have two irreconcilable fates attributed to them. According to the Xinian, they were killed by Shang loyalists; according to the transmitted tradition, most notably the Shiji, they were killed by the duke of Zhou for rebelling against the crown.Footnote 71 If the Three Guardians are considered to be some other (unnamed) individuals, the problem disappears. Lu Yihan's inventive suggestion unfortunately creates further problems. One issue is that his theory does not explain why a number of pre-Qin and later texts specifically associate Geng, Viscount of Lu/Wugeng with Guan Shu and Cai Shu. Furthermore, although most ancient historical texts suggest that there was only one rebellion against Zhou authority during the minority of King Cheng, Lu Yihan's theory requires that there be two: one involving Shang dynasty loyalists and one involving Guan Shu and Cai Shu, who were princes of the Zhou ruling house. On the present evidence, the issue of identification cannot be resolved.

Source Text B

PERICOPE FIVE

23/23

![]() [蔡]哀侯取妻於陳, 賽[息]侯亦取妻於陳, 是賽為=[息媯. 息媯]𨟻[將]歸于賽[息]

[蔡]哀侯取妻於陳, 賽[息]侯亦取妻於陳, 是賽為=[息媯. 息媯]𨟻[將]歸于賽[息]

![]() [過]

[過]

![]() =[蔡. 蔡]哀侯命

=[蔡. 蔡]哀侯命

![]() =[止之], 24/24 曰: “以同生[姓]之古[故]必内[入].” 賽[息]為[媯]乃内[入]于

=[止之], 24/24 曰: “以同生[姓]之古[故]必内[入].” 賽[息]為[媯]乃内[入]于

![]() =[蔡; 蔡]哀侯妻之. 賽[息]侯弗訓[順], 乃

=[蔡; 蔡]哀侯妻之. 賽[息]侯弗訓[順], 乃

![]() [使]人于楚文王 25/25 曰: “君

[使]人于楚文王 25/25 曰: “君

![]() [來]伐我. 我𨟻[將]求

[來]伐我. 我𨟻[將]求

![]() [救]於

[救]於

![]() [蔡], 君

[蔡], 君

![]() [焉]敗之.” 文王𨑓[起]𠂤[師]伐賽[息]; 賽[息]侯求

[焉]敗之.” 文王𨑓[起]𠂤[師]伐賽[息]; 賽[息]侯求

![]() [救]於

[救]於

![]() =[蔡. 蔡]哀侯

=[蔡. 蔡]哀侯

![]() [率]币[師] 26/26 以

[率]币[師] 26/26 以

![]() [救]賽[息]. 文王敗之於新[莘]; 雘[獲]哀侯以歸. 文王為客於賽[息],

[救]賽[息]. 文王敗之於新[莘]; 雘[獲]哀侯以歸. 文王為客於賽[息],

![]() [蔡]侯與從. 賽[息]侯以文 27/27 王㱃[飲]酒.

[蔡]侯與從. 賽[息]侯以文 27/27 王㱃[飲]酒.

![]() [蔡]侯智[知]賽[息]侯之誘𠮯[己]也. 亦告文王曰: “賽[息]侯之妻甚

[蔡]侯智[知]賽[息]侯之誘𠮯[己]也. 亦告文王曰: “賽[息]侯之妻甚

![]() [美]. 君必命見之.” 文 28/28 王命見之. 賽[息]侯

[美]. 君必命見之.” 文 28/28 王命見之. 賽[息]侯

![]() [辭], 王固命見之. 既見之還. 昷[明]

[辭], 王固命見之. 既見之還. 昷[明]

![]() [歲]起𡶫[師]伐賽[息], 克之, 殺賽[息]侯取 29/29 賽[息]為[媯]以歸: 是生

[歲]起𡶫[師]伐賽[息], 克之, 殺賽[息]侯取 29/29 賽[息]為[媯]以歸: 是生

![]() 堵囂[敖]及成王. 文王以北啓出方成[城], 圾

堵囂[敖]及成王. 文王以北啓出方成[城], 圾

![]() 於汝, 改

於汝, 改

![]() 於陳,

於陳,

![]() [焉] 30/30 取邨[頓]以贛[恐]陳侯.ㄴ

[焉] 30/30 取邨[頓]以贛[恐]陳侯.ㄴ

23/23 Marquis Ai of Cai (r. 694–675 b.c.e.) took a wife from Chen and the marquis of Sai (Xi) (d. 683 b.c.e.) also took a wife from Chen: this was Lady Gui of Sai.Footnote 72 Lady Gui of Sai was travelling to her new home in Sai; when she passed through Cai; Marquis Ai of Cai gave orders to stop her. 24/24 He said: “Given that you are a member of the same clan, you must enter [the capital].”Footnote 73 Lady Gui of Sai thus entered Cai and Marquis Ai of Cai raped her.Footnote 74 The marquis of Sai bore a grudge about this, so he sent a messenger to King Wen of Chu 25/25 to say: “If you, my lord, come and attack me, I will request assistance from Cai and then you can defeat them.” King Wen raised an army and attacked Sai, and the marquis of Sai requested assistance from Cai. Marquis Ai of Cai led his army 26/26 to rescue Sai. King Wen defeated them at Xin, capturing Marquis Ai alive and taking him home with him. King Wen went on a visit to Sai, and the marquis of Cai went with him; when the marquis of Sai offered a toast to King 27/27 Wen, the marquis of Cai realized that the marquis of Sai had tricked him. Then he said to King Wen: “The wife of the marquis of Sai is very beautiful; you really should order her to appear.” King 28/28 Wen gave orders that she be presented and when the marquis of Sai refused, the king insisted that she had to appear. After he saw her, he sent her back. The following year, he raised an army and attacked Sai, conquering them. He killed the marquis of Sai and took 29/29 Lady Gui home with him: she gave birth to Du'ao (r. 676–672 b.c.e.) and King Cheng (r. 671–626 b.c.e.).Footnote 75 To the north, King Wen opened up land [on the far side of the] Fangcheng Mountains, setting the border at the Ru River.Footnote 76 He put his troops into battle formation at Chen, and then 30/30 captured the city of Cun (Dun) in order to strike fear into the marquis of Chen.

PERICOPE FIFTEEN

73/74 楚

![]() [莊]王立, 吳人服于楚. 陳公子

[莊]王立, 吳人服于楚. 陳公子

![]() [徵]䣄[舒]取妻于奠[鄭]穆公, 是少

[徵]䣄[舒]取妻于奠[鄭]穆公, 是少

![]() .

.

![]() [莊]王立十又五年, 74/75 陳公子

[莊]王立十又五年, 74/75 陳公子

![]() [徵]余[舒]殺亓[其]君霝[靈]公.

[徵]余[舒]殺亓[其]君霝[靈]公.

![]() [莊]王

[莊]王

![]() [率]𠂤[師]回[圍]陳. 王命

[率]𠂤[師]回[圍]陳. 王命

![]() [申]公屈𠳄[巫]𨒙[適]秦求𠂤[師], 𠭁[得]𠂤[師]以 75/76

[申]公屈𠳄[巫]𨒙[適]秦求𠂤[師], 𠭁[得]𠂤[師]以 75/76

![]() [來]. 王内[入]陳殺

[來]. 王内[入]陳殺

![]() [徵]余[舒], 取亓[其]室以

[徵]余[舒], 取亓[其]室以

![]() [予]

[予]

![]() [申]公. 連尹襄老與之争, 敚之少

[申]公. 連尹襄老與之争, 敚之少

![]() . 連尹

. 連尹

![]() [止]於河 76/77 澭[雍]. 亓[其]子墨[黑]要也. 或[又]室少

[止]於河 76/77 澭[雍]. 亓[其]子墨[黑]要也. 或[又]室少

![]() .

.

![]() [莊]王即殜[世], 龏[共]王即立[位]. 墨[黑]要也死, 司馬子反與

[莊]王即殜[世], 龏[共]王即立[位]. 墨[黑]要也死, 司馬子反與

![]() [申] 77/78 公争少

[申] 77/78 公争少

![]() .

.

![]() [申]公曰: “氏[是]余受妻也.” 取以為妻. 司馬不訓[順]

[申]公曰: “氏[是]余受妻也.” 取以為妻. 司馬不訓[順]

![]() [申]公. 王命

[申]公. 王命

![]() [申]公

[申]公

![]() [聘]於齊.

[聘]於齊.

![]() [申] 78/79 公

[申] 78/79 公

![]() [竊]載少

[竊]載少

![]() 以行, 自齊述[遂]逃𨒙[適]晉, 自晉𨒙[適]吳.

以行, 自齊述[遂]逃𨒙[適]晉, 自晉𨒙[適]吳.

![]() [焉]

[焉]

![]() [始]迵[通]吳, 晉之

[始]迵[通]吳, 晉之

![]() [路], 教吳人反[叛]楚. 79/80 以至霝=王=[靈王, 靈王]伐吴為南

[路], 教吳人反[叛]楚. 79/80 以至霝=王=[靈王, 靈王]伐吴為南

![]() [懷]之行執吴王子鱥[蹶]䌛[由]吴人

[懷]之行執吴王子鱥[蹶]䌛[由]吴人

![]() [焉]或[又]服于楚. 霝[靈]王即殜[世]; 80/81 兢[景]坪[平]王即立[位]. 少币[師]亡[無]

[焉]或[又]服于楚. 霝[靈]王即殜[世]; 80/81 兢[景]坪[平]王即立[位]. 少币[師]亡[無]

![]() [極]

[極]

![]() [讒]連尹

[讒]連尹

![]() [奢]而殺之. 亓[其]子五[伍]員與五[伍]之雞逃

[奢]而殺之. 亓[其]子五[伍]員與五[伍]之雞逃

![]() [歸]吴. 五[伍]雞𨒫[將] 81/82 吴人以回[圍]州

[歸]吴. 五[伍]雞𨒫[將] 81/82 吴人以回[圍]州

![]() [來]為長

[來]為長

![]() [壑]而

[壑]而

![]() [洍]之, 以敗楚𠂤[師]: 是雞父之

[洍]之, 以敗楚𠂤[師]: 是雞父之

![]() [洍]. 兢[景]坪[平]王即殜[世]; 卲[昭]王即 82/83 立[位]. 五[伍]員為吴大

[洍]. 兢[景]坪[平]王即殜[世]; 卲[昭]王即 82/83 立[位]. 五[伍]員為吴大

![]() [宰]; 是教吴人反楚. 邦之者[諸]侯以敗楚𠂤[師]于白[柏]

[宰]; 是教吴人反楚. 邦之者[諸]侯以敗楚𠂤[師]于白[柏]

![]() [舉]述[遂]内[入]郢. 卲[昭]王

[舉]述[遂]内[入]郢. 卲[昭]王

![]() [歸] 83/84

[歸] 83/84

![]() [随]與吴人

[随]與吴人

![]() [戰]于析. 吴王子㫳[晨]𨟻[將]𨑓[起]𥛔[禍]於吴=[吴. 吴]王盍[闔]

[戰]于析. 吴王子㫳[晨]𨟻[將]𨑓[起]𥛔[禍]於吴=[吴. 吴]王盍[闔]

![]() [盧]乃

[盧]乃

![]() [歸]; 卲[昭]王

[歸]; 卲[昭]王

![]() [焉]

[焉]

![]() [復]邦.

[復]邦.

73/74 When King Zhuang of Chu (r. 613–591 b.c.e.) was in power, the Wu people submitted to the authority of Chu.Footnote 77 The nobleman from Chen, [Xia] Zhengshu obtained a wife from Lord Mu of Zheng (r. 627–606 b.c.e.): this was Shaomeng. In the fifteenth year of the reign of King Zhuang [599 b.c.e.], 74/75 the nobleman from Chen, Zhengshu, killed his ruler, Lord Ling (r. 613–599 b.c.e.), and King Zhuang led the army to lay siege to Chen. His Majesty ordered Qu Wu, the lord of Shen, to go to Qin to ask for an army; when he obtained the army, 75/76 he returned.Footnote 78 His Majesty entered Chen and killed [Xia] Zhengshu, taking over his entire household, and presenting it to the lord of Shen.Footnote 79 The lianyin, Xiang Lao, competed with him and stole Lady Shaomeng away; the lianyin was later taken prisoner at He 76/77 yong.Footnote 80 His son was Moyao [Heiyao]. He also married Lady Shaomeng.Footnote 81 King Zhuang then passed away and King Gong (r. 590–560 b.c.e.) was established. Moyao also died and the Minister of War, Prince Fan, and the lord of Shen 77/78 fought for possession of Lady Shaomeng. The lord of Shen said: “This is my appointed wife,” and he took her as his wife. The Minister of War held a grudge against the lord of Shen about this. The king ordered the lord of Shen to go on a diplomatic mission to Qi; the lord of 78/79 Shen secretly took Lady Shaomeng with him. From Qi they fled to Jin and from Jin they travelled to Wu. Thus for the first time [he gained knowledge of] the routes that led to Wu and Jin, and he taught the people of Wu to rebel against Chu.Footnote 82 79/80 In the time of King Ling (r. 540–529 b.c.e.), King Ling attacked Wu and conducted the Nanhuai campaign, [during which] he captured Prince Jueyou of Wu.Footnote 83 The people of Wu then submitted to the authority of Chu. When King Ling passed away,Footnote 84 80/81 King Jingping (r. 528–516 b.c.e.) took the throne.Footnote 85 The Junior Preceptor [Fei] Wuji slandered the lianyin [Wu] She and killed him; his sons Wu Yuan (d. 484 b.c.e.) and Wu Zhi Ji escaped and fled to Wu.Footnote 86 Wu Ji took command 81/82 of the people of Wu and laid siege to Zhoulai, building a long trench and then flooding it; thus he defeated the Chu army. This is the Canal of Elder Ji. When King Jingping passed away, King Zhao (r. 515–489 b.c.e.) then 82/83 took the throne. Wu Yuan became the chancellor of Wu.Footnote 87 Then he instructed the people of Wu to rebel against Chu. The lords of the states then defeated the Chu army at Boju, before entering Ying. King Zhao fled to 83/84 Sui, and he fought a battle with the people of Wu at Xi.Footnote 88 Prince Zhen of Wu was about to start an uprising in Wu, so King Helu of Wu (r. 514–496 b.c.e.) then went home.Footnote 89 King Zhao was thus able to return to his state.

* * *

Pericope fifteen begins with an account of one of the great scandals of the Spring and Autumn period: the death of Lord Ling of Chen at the hands of the Xia family. The Xinian here points to the existence of an error within not only the Zuozhuan, but also all the other transmitted texts which recount this story. The issue is one of chronology. Lady Xia Ji was the daughter of Lord Mu of Zheng (who died in 606 b.c.e.), and according to the Zuozhuan, in the year 600 b.c.e., she was engaged in sexual relationships not only with Lord Ling of Chen, but also two of his ministers—Kong Ning 孔寧 and Yi Xingfu 儀行父. The following year, her son, Xia Zhengshu 夏徵叔, was so furious at the aspersions cast by his lordship upon his paternity that he assassinated Lord Ling. Lady Xia Ji is next mentioned in the year 589 b.c.e., when she eloped with Wu Chen 巫臣 (Qu Wu).Footnote 90 The problem with this sequence of events is that Lady Xia Ji would have been quite old for a Bronze Age woman who is being portrayed as incredibly beautiful and attractive: as an absolute minimum she was in her early thirties on the death of Lord Ling and in her middle forties at the time of leaving Chu. In the Han dynasty and later, thanks to this belief in her age, the legend grew up that Lady Xia Ji had achieved eternal youth and attractiveness by mastering esoteric sexual techniques; as a result she plays an important part in the development of Chinese erotica.Footnote 91 However, in terms of the historical events, it is likely that the Xinian is correct. There was no son of Lady Xia Ji, and Lord Ling of Chen was murdered by her husband. This would then reduce her age: Lady Xia Ji's marriages probably occurred when she was in her late teens and early twenties. The mistake in the Zuozhuan has ended up taking on a life of its own.

Lady Xia Ji's story segues into that of Wu Zixu, who, like Qu Wu, first arrived in the kingdom of Wu as a refugee from Chu. Many ancient texts mention that when Wu She was slandered by Fei Wuji, his two sons initially both escaped arrest. Supposedly the older of his two sons, Wu Shang 伍尚, returned to Chu to be executed with his father; Wu Yuan escaped to the kingdom of Wu.Footnote 92 The Xinian states that two brothers travelled to Wu, and that Wu Ji was the commander of the army that destroyed Zhoulai in 529 b.c.e.Footnote 93 Wu Zixu is often said to be the single best recorded individual in the history of the Spring and Autumn period, but if the Xinian is correct, even such basic facts as the survival of his brother have been recorded incorrectly within the transmitted tradition.Footnote 94 The information that his brother apparently also served as a senior military commander in Wu is particularly interesting, for it means that the startling victories attributed to Wu Zixu may have been the work of two men and not one.

Source Text C

PERICOPE SIX

31/31 晉獻公之婢妾曰驪姬, 欲亓[其]子![]() [奚]

[奚]

![]() [齊]之為君也. 乃

[齊]之為君也. 乃

![]() [讒]大子龍共君而殺之. 或[又]

[讒]大子龍共君而殺之. 或[又]

![]() [讒] 32/32 惠公及文=公=[文公. 文公]奔翟[狄]; 惠公奔于梁. 獻公

[讒] 32/32 惠公及文=公=[文公. 文公]奔翟[狄]; 惠公奔于梁. 獻公

![]() [卒]乃立

[卒]乃立![]() [奚]

[奚]

![]() [齊]. 亓[其]夫=[大夫]里之克乃殺

[齊]. 亓[其]夫=[大夫]里之克乃殺![]() [奚]

[奚]

![]() [齊] 33/33 而立亓[其]弟悼子. 里之克或[又]殺悼子. 秦穆公乃内惠公于晉. 惠公賂秦公曰: “我 34/34 句[後]果内[入], 囟[使]君涉河至于梁城.” 惠公既内[入], 乃

[齊] 33/33 而立亓[其]弟悼子. 里之克或[又]殺悼子. 秦穆公乃内惠公于晉. 惠公賂秦公曰: “我 34/34 句[後]果内[入], 囟[使]君涉河至于梁城.” 惠公既内[入], 乃

![]() [背]秦公, 弗

[背]秦公, 弗

![]() [予]. 立六年, 秦公

[予]. 立六年, 秦公

![]() [率]𠂤[師]与[與] 35/35 惠公

[率]𠂤[師]与[與] 35/35 惠公

![]() [戰]于倝[韓],

[戰]于倝[韓],

![]() [止]惠公以歸. 惠公

[止]惠公以歸. 惠公

![]() [焉]以亓[其]子褱[懷]公為執[質]于秦=[秦. 秦]穆公以亓[其]子妻之. 36/36 文公十又二年居翟=[狄. 狄]甚善之而弗能内[入]. 乃𨒙[適]齊=[齊. 齊]人善之. 𨒙[適]宋=[宋. 宋]善之, 亦莫 37/37 之能内[入]. 乃𨒙[適]

[焉]以亓[其]子褱[懷]公為執[質]于秦=[秦. 秦]穆公以亓[其]子妻之. 36/36 文公十又二年居翟=[狄. 狄]甚善之而弗能内[入]. 乃𨒙[適]齊=[齊. 齊]人善之. 𨒙[適]宋=[宋. 宋]善之, 亦莫 37/37 之能内[入]. 乃𨒙[適]

![]() =[衛. 衛]人弗善, 𨒙[適]奠=[鄭. 鄭]人弗善, 乃𨒙[適]楚. 褱[懷]公自秦逃歸, 秦穆公乃訋[召] 38/38 文公於楚, 囟[使]

=[衛. 衛]人弗善, 𨒙[適]奠=[鄭. 鄭]人弗善, 乃𨒙[適]楚. 褱[懷]公自秦逃歸, 秦穆公乃訋[召] 38/38 文公於楚, 囟[使]

![]() [襲]褱[懷]公之室. 晉惠公

[襲]褱[懷]公之室. 晉惠公

![]() [卒], 褱[懷]公即立[位]. 秦人𨑓[起]𠂤[師]以内文公于晉=[晉. 晉]人 39/39 殺褱[懷]公而立文公. 秦晉

[卒], 褱[懷]公即立[位]. 秦人𨑓[起]𠂤[師]以内文公于晉=[晉. 晉]人 39/39 殺褱[懷]公而立文公. 秦晉

![]() [焉]

[焉]

![]() [始]會好穆[戮]力同心. 二邦伐𦂍[鄀]

[始]會好穆[戮]力同心. 二邦伐𦂍[鄀]

![]() [徙]之

[徙]之

![]() [中]城回[圍]商

[中]城回[圍]商

![]() [密],

[密],

![]() [止] 40/40

[止] 40/40

![]() [申]公子義[儀]以歸.ㄴ

[申]公子義[儀]以歸.ㄴ

31/31 Lord Xian of Jin's (r. 676–651 b.c.e.) favourite concubine was named Lady Li Ji, and she wanted her son, Xiqi, to become the ruler.Footnote 95 Therefore she slandered the Heir Apparent, Lord Long (Gong), and killed him.Footnote 96 She also slandered 32/32 Lord Hui (r. 650–637 b.c.e.) and Lord Wen (r. 636–628 b.c.e.). Lord Wen fled to the Di people, while Lord Hui fled to Liang. When Lord Xian died, Xiqi was established. Grandee Li Zhi Ke then killed Xiqi. 33/33 They established his younger brother Daozi.Footnote 97 Li Zhi Ke also killed Daozi.Footnote 98 Afterwards Lord Mu of Qin (r. 659–621 b.c.e.) installed Lord Hui in power in Jin. Lord Hui had bribed Lord Mu, saying: “If 34/34 in the future I am indeed able to return [to my country], I will give you the land on the other side of the Yellow River right up to the city of Liang.” When Lord Hui was installed in power, he turned his back on Lord Mu and refused to give him [this land]. In the sixth year of his reign [645 b.c.e.], Lord Mu led his army to do battle with 35/35 Lord Hui at Han, capturing Lord Hui and taking him home with him. Lord Hui then sent his son, Lord Huai (r. 637 b.c.e.), to go as a hostage to Qin. Lord Mu of Qin gave him his daughter in marriage. 36/36 Lord Wen spent twelve years living with the Di people and they treated him very well, but they were not able to put him in power. He then travelled to Qi, where the people of Qi treated him well, and he travelled to Song, where the people of Song treated him well, but they too were unable 37/37 to put him in power. He travelled through Wei, but the people of Wei did not treat him well; he travelled through Zheng, but the people of Zheng did not treat him well; then he moved on to Chu.Footnote 99 Lord Huai escaped from Qin and went home, whereupon Lord Mu of Qin summoned 38/38 Lord Wen from Chu, ordering him to take over the household of Lord Huai.Footnote 100 When Lord Hui of Jin died, Lord Huai succeeded him. The people of Qin raised an army in order to install Lord Wen in Jin. The people of Jin killed 39/39 Lord Huai and established Lord Wen.Footnote 101 From this point onwards Qin and Jin began to be allies, working together in harmony. The two states attacked Ruo, before moving on to Zhongcheng; they laid siege to Shangmi, and captured 40/40 the Honourable Yi of Shen, returning home with him.Footnote 102

PERICOPE SEVEN

41/41 晉文公立四年, 楚成王

![]() [率]者[諸]侯以回[圍]宋, 伐齊, 戌㝅[穀], 居

[率]者[諸]侯以回[圍]宋, 伐齊, 戌㝅[穀], 居

![]() [緡]. 晉文公囟[思]齊及宋之 42/42 惪[德], 乃及秦𠂤[師]回[圍]曹及五

[緡]. 晉文公囟[思]齊及宋之 42/42 惪[德], 乃及秦𠂤[師]回[圍]曹及五

![]() [鹿], 伐

[鹿], 伐

![]() [衛]以敚[脱]齊之戍及宋之回[圍]. 楚王豫[舍]回[圍]歸居方城. 43/43 命[令]尹子玉述[遂]

[衛]以敚[脱]齊之戍及宋之回[圍]. 楚王豫[舍]回[圍]歸居方城. 43/43 命[令]尹子玉述[遂]

![]() [率]奠[鄭],

[率]奠[鄭],

![]() [衛], 陳,

[衛], 陳,

![]() [蔡], 及羣䜌[蠻]𡰥[夷]之𠂤[師]以交文=公=[文公. 文公]

[蔡], 及羣䜌[蠻]𡰥[夷]之𠂤[師]以交文=公=[文公. 文公]

![]() [率]秦, 齊, 宋, 及羣戎 44/44 之𠂤[師]以敗楚𠂤[師]於城

[率]秦, 齊, 宋, 及羣戎 44/44 之𠂤[師]以敗楚𠂤[師]於城

![]() [濮]. 述[遂]朝周襄王于衡澭[雍]. 獻楚俘馘

[濮]. 述[遂]朝周襄王于衡澭[雍]. 獻楚俘馘

![]() [盟]者[諸]侯於

[盟]者[諸]侯於

![]() [踐]土.ㄴ

[踐]土.ㄴ

41/41 In the fourth year of the reign of Lord Wen of Jin [633 b.c.e.], King Cheng of Chu led the various lords to lay siege to Song and attack Qi,Footnote 103 stationing troops in Gu and occupying Min.Footnote 104 Lord Wen of Jin was cognizant of Qi and Song's 42/42 virtuous behavior, so in concert with the Qin army he laid siege to Cao and Wulu, as well as attacking Wei, in order to lift the occupation of Qi and the siege of Song.Footnote 105 The king of Chu did indeed lift the siege and go home, taking up residence [beyond] the Fangcheng Mountains.Footnote 106 43/43 The Prime Minister, Ziyu, then led the armies of Zheng, Wei, Chen, Cai, and the various Man and Yi peoples to intercept Lord Wen; Lord Wen led the armies of Qin, Qi, Song, and the various Rong peoples 44/44 to defeat the Chu army at Chengpu.Footnote 107 He then paid court to King Xiang of Zhou (r. 651–619 b.c.e.) at Hengyong and presented the captives and ears from Chu.Footnote 108 He performed a blood covenant with the other lords at Jiantu.Footnote 109

PERICOPE EIGHT

45/45 晉文公立七年秦晉回[圍]奠=[鄭. 鄭]降秦, 不降晉=[晉. 晉]人以不憖. 秦人豫戍於奠=[鄭. 鄭]人䜴[屬]北門之

![]() [管]於秦=之= 46/46 戍=人[秦之戍人. 秦之戍人]

[管]於秦=之= 46/46 戍=人[秦之戍人. 秦之戍人]

![]() [使]人

[使]人

![]() [歸]告曰: “我既𠭁[得]奠[鄭]之門

[歸]告曰: “我既𠭁[得]奠[鄭]之門

![]() [管], 也

[管], 也

![]() [來]

[來]

![]() [襲]之.”Footnote

110

秦𠂤[師]𨟻[將]東

[襲]之.”Footnote

110

秦𠂤[師]𨟻[將]東

![]() [襲]奠=[鄭. 鄭]之賈人弦高𨟻[將]西 47/47 市遇之;乃以奠[鄭]君之命

[襲]奠=[鄭. 鄭]之賈人弦高𨟻[將]西 47/47 市遇之;乃以奠[鄭]君之命

![]() [勞]秦三

[勞]秦三

![]() [帥]. 秦𡶫[師]乃

[帥]. 秦𡶫[師]乃

![]() [復], 伐顝[滑], 取之. 晉文公

[復], 伐顝[滑], 取之. 晉文公

![]() [卒]未

[卒]未

![]() [葬], 襄公新[親] 48/48

[葬], 襄公新[親] 48/48

![]() [率]𠂤[師]御[禦]秦𠂤[師]于山

[率]𠂤[師]御[禦]秦𠂤[師]于山

![]() [崤], 大敗之. 秦穆公欲與楚人為好,

[崤], 大敗之. 秦穆公欲與楚人為好,

![]() [焉]

[焉]

![]() [脱]

[脱]

![]() [申]公義[儀]囟[使]

[申]公義[儀]囟[使]

![]() [歸]求成. 秦

[歸]求成. 秦

![]() [焉] 49/49

[焉] 49/49

![]() [始]與晉𢽞[執]

[始]與晉𢽞[執]

![]() , 与[與]楚為好.ㄴ

, 与[與]楚為好.ㄴ

45/45 In the seventh year of the reign of Lord Wen of Jin [630 b.c.e.], Qin and Jin laid siege to Zheng, and Zheng surrendered to Qin, but did not surrender to Jin. The people of Jin were unhappy about this. The people of Qin occupied Zheng and the people of Zheng handed over authority for the northern gate to the occupying forces 46/46 from Qin.Footnote 111 The occupying forces of Qin sent someone home to report: “We have obtained control over the gates of Zheng; come secretly and make a surprise attack on them.”Footnote 112 The Qin army was about to go east and make a surprise attack upon Zheng, but the Zheng merchant Xian Gao who was heading west 47/47 to trade, met with them; in accordance with an order from the ruler of Zheng he feasted the three armies of Qin. The army then returned; they attacked Hua and captured it.Footnote 113 Lord Wen of Jin had died but was not yet buried when Lord Xiang (r. 627–621 b.c.e.) personally 48/48 led his armies to intercept the Qin army at Xiao and inflicted a terrible defeat upon them.Footnote 114 Lord Mu of Qin wanted to make an alliance with the people of Chu, so he released the Honourable Yi of Shen and sent him home to request a peace treaty. From this point onwards, Qin 49/49 began to be hostile towards Jin, and ally with Chu.

PERICOPE NINE

50/50 晉襄公

![]() [卒], 霝[靈]公高幼夫=[大夫]聚𠰔[謀]曰: “君幼未可舉承也. 母[毋]乃不能邦? 猷求

[卒], 霝[靈]公高幼夫=[大夫]聚𠰔[謀]曰: “君幼未可舉承也. 母[毋]乃不能邦? 猷求

![]() [强]君.” 乃命 51/51 右[左]行𤻻[蔑]与與

[强]君.” 乃命 51/51 右[左]行𤻻[蔑]与與

![]() [随]會卲[召]襄公之弟癕[雍]也于秦. 襄而【夫】人

[随]會卲[召]襄公之弟癕[雍]也于秦. 襄而【夫】人

![]() [聞]之乃

[聞]之乃

![]() 抱霝[靈]公以

抱霝[靈]公以

![]() [號]于廷曰: “死人可[何]辠[罪]? 52/52 生人可[何]

[號]于廷曰: “死人可[何]辠[罪]? 52/52 生人可[何]

![]() [辜]? 豫[舍]亓[其]君之子弗立而卲[召]人于外, 而

[辜]? 豫[舍]亓[其]君之子弗立而卲[召]人于外, 而

![]() [焉]𨟻[將]

[焉]𨟻[將]

![]() [寘]此子也.” 夫=[大夫]

[寘]此子也.” 夫=[大夫]

![]() [閔]乃

[閔]乃

![]() [皆]北[背]之曰: “我莫命卲[招] 52/53 之.” 乃立霝[靈]公

[皆]北[背]之曰: “我莫命卲[招] 52/53 之.” 乃立霝[靈]公

![]() [焉]

[焉]

![]() [葬]襄公.ㄴ

[葬]襄公.ㄴ

50/50 When Lord Xiang of Jin died, Lord Ling [whose personal name was] Gao (r. 620–607 b.c.e.) was but a small child.Footnote 115 The grandees gathered to discuss the situation and said: “His lordship is a young child and he cannot yet assume responsibility. What is to be done about the fact that he is not able to govern the country? We need an adult ruler!”Footnote 116 They ordered 51/51 [Xian] Mie, Infantry General of the Left,Footnote 117 and [Shi] Hui of Sui to summon Lord Xiang's younger brother, Yong, from Qin.Footnote 118 When Lord Xiang's wife heard this, she caused a scene in the court, holding Lord Ling in her arms. She said: “What crime has the dead man committed? 52/52 Why should the living be punished? You have abandoned your ruler's son and refused to establish him, seeking someone from outside: are you really going to set aside this child?”Footnote 119 The grandees panicked and they all betrayed [those who had been sent on this mission]. They said: “No-one has given orders to summon 52/53 him.”Footnote 120 They then established Lord Ling and afterwards buried Lord Xiang.Footnote 121

PERICOPE TEN

53/54 秦康公

![]() [率]𠂤[師]以

[率]𠂤[師]以

![]() [送]癕[雍]子. 晉人𨑓[起]𠂤[師]敗之于

[送]癕[雍]子. 晉人𨑓[起]𠂤[師]敗之于

![]()

![]() . 右[左]行𤻻[蔑]

. 右[左]行𤻻[蔑]

![]() [随]會不敢

[随]會不敢

![]() [歸], 述[遂] 54/55 奔秦. 霝[靈]公高立六年, 秦公以

[歸], 述[遂] 54/55 奔秦. 霝[靈]公高立六年, 秦公以

![]() [戰]于䏉

[戰]于䏉

![]() 之古[故],

之古[故],

![]() [率]𠂤[師]為河曲之

[率]𠂤[師]為河曲之

![]() [戰].ㄴ

[戰].ㄴ

53/54 Lord Kang of Qin (r. 620–609 b.c.e.) led his army to escort Yong, the unratified ruler. The people of Jin raised an army and defeated them at Jinyin.Footnote 122 [Xian] Mie, the Infantry General of the Left, and [Shi] Hui of Sui did not dare to go home, so 54/55 they fled to Qin. When Gao, Lord Ling [of Jin] had been established for six years [615 b.c.e.], the ruler of Qin led his army at the battle of Hequ, [in order to avenge] the battle of Jinyin.Footnote 123

* * *

The stories found in Source Text C form a group with a strong chronological connection. Furthermore, this seems to be very closely related to the transmitted tradition, providing an account of events that is extremely similar—though consistently shorter and less detailed—to that given in the Zuozhuan. Yuri Pines suggests that rather than the Xinian being considered as a précis of the Zuozhuan, that some of the anecdotes incorporated into this text (here grouped into Source Text C) may have been derived from the same history of the state of Jin as that used by the compilers of the Zuozhuan. However, where the Zuozhuan adds more detail, records more speeches, and provides further moralizations and didactic messages, the Xinian pares down the information and presents it in a bald, skeletal form, concentrating on the key historical events and their most significant consequences.Footnote 124 It is the contention of this article that material found in other source texts for the Xinian, though sometimes recording the same events, lacks the really close connection with the Zuozhuan seen in Source Text C.

Source Text D

PERICOPE ELEVEN

55/56 楚穆王立八年, 王會者[諸]侯于发[厥]![]() [貉], 𨟻[將]以伐宋=(宋. 宋)右币[師]芋[華]孫兀[元]欲

[貉], 𨟻[將]以伐宋=(宋. 宋)右币[師]芋[華]孫兀[元]欲

![]() [勞]楚币[師]. 乃行 56/57 穆王思[使]毆[驅]

[勞]楚币[師]. 乃行 56/57 穆王思[使]毆[驅]

![]() [孟]者[諸]之麋

[孟]者[諸]之麋

![]() [徙]之徒

[徙]之徒

![]() . 宋公為右[左]芋[盂]; 奠[鄭]伯為右芋[盂].

. 宋公為右[左]芋[盂]; 奠[鄭]伯為右芋[盂].

![]() [申]公弔[叔]侯智[知]之, 宋 57/58 公之車𡖶[暮]

[申]公弔[叔]侯智[知]之, 宋 57/58 公之車𡖶[暮]

![]() [駕]用

[駕]用

![]() [抶]宋公之馭[御]. 穆王即殜[世]

[抶]宋公之馭[御]. 穆王即殜[世]

![]() [莊]王即立[位].

[莊]王即立[位].

![]() [使]孫[申]白[伯]亡[無]愄[畏]

[使]孫[申]白[伯]亡[無]愄[畏]

![]() [聘]于齊, 段[假]

[聘]于齊, 段[假]

![]() [路] 58/59 於宋=[宋. 宋]人是古[故]殺孫[申]白[伯]亡[無]愄[畏],

[路] 58/59 於宋=[宋. 宋]人是古[故]殺孫[申]白[伯]亡[無]愄[畏],

![]() [奪]亓[其]玉帛.

[奪]亓[其]玉帛.

![]() [莊]王

[莊]王

![]() [率]𠂤[師]回[圍]宋九月. 宋人

[率]𠂤[師]回[圍]宋九月. 宋人

![]() [焉]為成. 以女子 59/60 與兵車百𨌤[乘], 以芋[華]孫兀[元]為

[焉]為成. 以女子 59/60 與兵車百𨌤[乘], 以芋[華]孫兀[元]為

![]() [質].ㄴ

[質].ㄴ

55/56 In the eighth year [618 b.c.e.] of the reign of King Mu of Chu (r. 625–614 b.c.e.), the king met with the other lords at You [one unknown character] (Juehao), for he was going to attack Song.Footnote 125 The commander of the right army of Song, Hua Sunwu (Sunyuan), wanted to feast the Chu army. He then proceeded with 56/57 King Mu to hunt deer in Mengzhu, [after which] they moved on to Tulin.Footnote 126 The duke of Song was in the left hunting chariot; the earl of Zheng was in the right hunting chariot. The lord of Shen, Shuhou, found out about this, and when the duke 57/58 of Song's chariot set out late, he whipped the duke of Song's charioteer.Footnote 127 When King Mu passed away, King Zhuang came to the throne. He sent Wuwei, the earl of Shen, on a diplomatic mission to Qi, during which he borrowed a road 58/59 from Song. The people of Song killed Wuwei, the earl of Shen, for this reason and stole his jade and silk.Footnote 128 King Zhuang led his army to lay siege to Song for nine months. The people of Song then made peace. They gave him men and women, 59/60 as well as one hundred chariots; in addition, they gave him Hua Sunwu as a hostage.Footnote 129

PERICOPE TWELVE

60/61 楚

![]() [莊]王立十又四年, 王會者[諸]侯于

[莊]王立十又四年, 王會者[諸]侯于

![]() [厲]; 奠[鄭]成公自

[厲]; 奠[鄭]成公自

![]() [厲]逃歸.

[厲]逃歸.

![]() [莊]王述[遂]加奠[鄭]

[莊]王述[遂]加奠[鄭]

![]() [亂]. 晉成 61/62 公會者[諸]侯以

[亂]. 晉成 61/62 公會者[諸]侯以

![]() [救]奠[鄭]. 楚𠂤[師]未還, 晉成公

[救]奠[鄭]. 楚𠂤[師]未還, 晉成公

![]() [卒]于扈.ㄴ

[卒]于扈.ㄴ

60/61 In the fourteenth year of the reign of King Zhuang of Chu [598 b.c.e.], His Majesty met with the other lords at Li.Footnote 130 Lord Cheng of Zheng fled homewards from Li,Footnote 131 so King Zhuang then provoked conflict in Zheng.Footnote 132 Lord Cheng of Jin (r. 607–600 b.c.e.) 61/62 met the other lords with a view to rescuing Zheng; before the Chu army had turned back, Lord Cheng of Jin died at Hu.Footnote 133

PERICOPE THIRTEEN

62/63 … 【莊】王回[圍]奠[鄭]三月. 奠[鄭]人為成. 晉中行林父

![]() [率]𠂤[師]

[率]𠂤[師]

![]() [救]奠[鄭].

[救]奠[鄭].

![]() [莊]王述[遂]北. 63/64 … 【楚】人明[盟].

[莊]王述[遂]北. 63/64 … 【楚】人明[盟].

![]() [趙]

[趙]

![]() [旃]不欲成, 弗卲[召], 𢎹[席]于楚軍之門. 楚人 64/65 被

[旃]不欲成, 弗卲[召], 𢎹[席]于楚軍之門. 楚人 64/65 被

![]() [駕]以𠂤[追]之, 述[遂]敗晉𠂤[師]于河【上】 …

[駕]以𠂤[追]之, 述[遂]敗晉𠂤[師]于河【上】 …

62/63 … Footnote 134 King [Zhuang] laid siege to Zheng for three months, whereupon the people of Zheng made peace. Zhonghang Linfu of Jin led the army to rescue Zheng, and King Zhuang then turned north. 63/64 … The people [of Chu] performed a blood covenant.Footnote 135 Zhao Zhan did not want this peace treaty. Since he could not make [the king of Chu] attend [a blood covenant], he took up position at the gate to the Chu army [camp].Footnote 136 The people of Chu 64/65 had to put armour onto their horses in order to chase him away. Then they defeated the Jin army at He[shang] … Footnote 137

PERICOPE SIXTEEN

84/85 楚龍[共]王立七年, 命[令]尹子𧝎[重]伐奠[鄭], 為𣲲之𠂤[師]. 晉兢[景]公會者[諸]侯以

![]() [救]鄭=[鄭. 鄭]人

[救]鄭=[鄭. 鄭]人

![]() [止]芸[鄖]公義[儀], 獻 85/86 者[諸]兢=公=[景公. 景公]以

[止]芸[鄖]公義[儀], 獻 85/86 者[諸]兢=公=[景公. 景公]以

![]() [歸]. 一年, 兢[景]公欲與楚人為好, 乃敚[脫]芸[鄖]公囟[使]

[歸]. 一年, 兢[景]公欲與楚人為好, 乃敚[脫]芸[鄖]公囟[使]

![]() [歸]求成. 龍[共]王

[歸]求成. 龍[共]王

![]() [使]芸[鄖]公

[使]芸[鄖]公

![]() [聘]於 86/87 晉,

[聘]於 86/87 晉,

![]() [且]許成. 兢[景]公

[且]許成. 兢[景]公

![]() [使]翟[糴]之伐[茷]

[使]翟[糴]之伐[茷]

![]() [聘]於楚,

[聘]於楚,

![]() [且]攸[修]成. 未還, 兢[景]公

[且]攸[修]成. 未還, 兢[景]公

![]() [卒].

[卒].

![]() [厲]公即立[位].

[厲]公即立[位].

![]() [共]王

[共]王

![]() [使]王 87/88 子㫳[辰]

[使]王 87/88 子㫳[辰]

![]() [聘]於晉, 或[又]攸[修]成. 王或[又]

[聘]於晉, 或[又]攸[修]成. 王或[又]

![]() [使]宋右币[師]芋[華]孫兀[元]行晉楚之成. 昷[明]

[使]宋右币[師]芋[華]孫兀[元]行晉楚之成. 昷[明]

![]() [歲], 楚王子

[歲], 楚王子

![]() [罷]會晉文 89/89 子

[罷]會晉文 89/89 子

![]() [燮]及者[諸]侯之夫=[大夫]明[盟]於宋. 曰: “爾[弭]天下之

[燮]及者[諸]侯之夫=[大夫]明[盟]於宋. 曰: “爾[弭]天下之

![]() [甲]兵.” 昷[明]

[甲]兵.” 昷[明]

![]() [歲],

[歲],

![]() [厲]公先起兵,

[厲]公先起兵,

![]() [率]𠂤[師]會者[諸]侯以伐 90/90 秦.

[率]𠂤[師]會者[諸]侯以伐 90/90 秦.

![]() =[至于]涇.

=[至于]涇.

![]() [共]王亦

[共]王亦

![]() [率]𠂤[師]回[圍]奠[鄭].

[率]𠂤[師]回[圍]奠[鄭].

![]() [厲]公

[厲]公

![]() [救]奠[鄭], 敗楚𠂤[師]於

[救]奠[鄭], 敗楚𠂤[師]於

![]() [鄢].

[鄢].

![]() [厲]公 亦見𥛔[禍], 以死亡𨒥[後].ㄴ

[厲]公 亦見𥛔[禍], 以死亡𨒥[後].ㄴ

84/85 In the seventh year [584 b.c.e.] of the reign of King Long (Gong) of Chu (r. 590–560 b.c.e.), the Prime Minister Zizhong attacked Zheng and stationed his army at Fan. Lord Jing of Jin (r. 599–581 b.c.e.) met with the other lords with a view to rescuing Zheng.Footnote 138 The people of Zheng arrested Yi, lord of Yun, and presented 85/86 him to Lord Jing.Footnote 139 Lord Jing returned home with him. One year later [583 b.c.e.], Lord Jing wanted to have a peace treaty with the people of Chu, so he released the lord of Yun and sent him home to request the peace treaty.Footnote 140 King Long sent the lord of Yun on a diplomatic visit to 86/87 Jin, furthermore, he agreed to the peace treaty. Lord Jing sent Di Zhi Fa to pay a diplomatic visit to Chu, whereupon the peace treaty was confirmed.Footnote 141 Before he had returned, Lord Jing of Jin died and Lord Li (r. 580–573 b.c.e.) succeeded. King Long sent Prince 87/88 Chen on a diplomatic visit to Jin, and again reconfirmed the peace treaty.Footnote 142 The king also sent the Song Preceptor of the Right, Hua Sunwu (Sunyuan), to enact the treaty between Chu and Jin. The following year [579 b.c.e.], Prince Ba of Chu met [Fan] Wen 89/89 zi [Shi] Xie of Jin and the grandees representing the other lords and they performed a blood covenant in Song.Footnote 143 They said: “Let us stop the fighting all over the world.”Footnote 144 The following year [578 b.c.e.], Lord Li was the first to raise an army and led his troops to meet the other lords, with a view to making an attack upon 90/90 Qin.Footnote 145 He arrived at Jing.Footnote 146 King Long also led his troops to lay siege to Zheng; but Lord Li rescued Zheng and defeated the Chu army at Yan. Lord Li then suffered disaster and died, leaving no descendants.Footnote 147

PERICOPE NINETEEN

104/104 楚霝[靈]王立既

![]() [縣]陳,

[縣]陳,

![]() [蔡]. 兢[景]坪[平]王即立[位], 改邦陳,

[蔡]. 兢[景]坪[平]王即立[位], 改邦陳,

![]() [蔡]之君, 囟[使]各

[蔡]之君, 囟[使]各

![]() [復]亓[其]邦. 兢[景]坪[平]王即殜[世], 卲[昭] 105/105 【王】即立[位]. 陳,

[復]亓[其]邦. 兢[景]坪[平]王即殜[世], 卲[昭] 105/105 【王】即立[位]. 陳,

![]() [蔡],

[蔡],

![]() [胡]反楚, 與吴人伐楚. 秦異公命子甫[蒲], 子虎

[胡]反楚, 與吴人伐楚. 秦異公命子甫[蒲], 子虎

![]() [率]𠂤[師]

[率]𠂤[師]

![]() [救]楚, 與楚𠂤[師]會伐陽[唐],

[救]楚, 與楚𠂤[師]會伐陽[唐],

![]() [縣]之. 106/106 卲[昭]王既

[縣]之. 106/106 卲[昭]王既

![]() [復]邦,

[復]邦,

![]() [焉]克

[焉]克

![]() [胡], 回[圍]

[胡], 回[圍]

![]() [蔡]. 卲[昭]王即殜[世]. 獻惠王立十又一年,

[蔡]. 卲[昭]王即殜[世]. 獻惠王立十又一年,

![]() [蔡]卲[昭]侯

[蔡]卲[昭]侯

![]() [申]懼, 自

[申]懼, 自

![]() [歸]於吴=[吴. 吴]縵[洩]用[庸], 107/107 以𠂤[師]逆

[歸]於吴=[吴. 吴]縵[洩]用[庸], 107/107 以𠂤[師]逆

![]() [蔡]卲[昭]侯, 居于州

[蔡]卲[昭]侯, 居于州

![]() [來]. 是下

[來]. 是下

![]() [蔡]. 楚人

[蔡]. 楚人

![]() [焉]

[焉]

![]() [縣]

[縣]

![]() [蔡].ㄴ

[蔡].ㄴ

104/104 When King Ling of Chu was on the throne, he made Chen and Cai into counties. When King Jingping was on the throne, he gave different territory to the rulers of Chen and Cai and restored each of them to their states.Footnote 148 When King Jingping passed away, [King] 105/105 Zhao was established. Chen, Cai, and Hu rebelled against Chu, and joined with the people of Wu in attacking Chu.Footnote 149 Lord Yi of Qin (r. 536–501 b.c.e.) ordered Zipu and Zihu to lead an army to rescue Chu; they met with the Chu army and attacked Tang, turning it into a county.Footnote 150 106/106 When King Zhao returned to his country, he attacked Hu and laid siege to Cai.Footnote 151 King Zhao passed away. In the eleventh year [478 b.c.e.] of King Xianhui (r. 488–432 b.c.e.),Footnote 152 Shen, Marquis Zhao of Cai (r. 518–491 b.c.e.) became frightened, so he personally gave his allegiance to Wu.Footnote 153 Man Yong (Xie Yong) 107/107 of Wu took the army to meet Marquis Zhao of Cai, and he took up residence at Zhoulai: this was Lower Cai.Footnote 154 The people of Chu then made Cai into a county.

PERICOPE TWENTY-ONE

114/114 楚柬[簡]大王立七年, 宋悼公朝于楚, 告以宋司城

![]() 之約公室. 王命莫囂[敖]昜為

之約公室. 王命莫囂[敖]昜為

![]() [率] 115/115𠂤[師]以定公室, 城黄池, 城罋[雍]丘. 晉𩲈[魏]𢍉[斯],

[率] 115/115𠂤[師]以定公室, 城黄池, 城罋[雍]丘. 晉𩲈[魏]𢍉[斯],

![]() [趙]

[趙]

![]() [浣],Footnote

155

倝[韓]啟章

[浣],Footnote

155

倝[韓]啟章

![]() [率]𠂤[師]回[圍]黄池,

[率]𠂤[師]回[圍]黄池,

![]() [迵]而歸之 116/116 於楚. 二年, 王命莫囂[敖]昜為

[迵]而歸之 116/116 於楚. 二年, 王命莫囂[敖]昜為

![]() [率]𠂤[師]

[率]𠂤[師]

![]() [侵]晉,

[侵]晉,

![]() [奪]宜昜[陽], 回[圍]赤

[奪]宜昜[陽], 回[圍]赤

![]() 以

以

![]() [復]黄池之𠂤[師]. 𩲈[魏]𢍉[斯],

[復]黄池之𠂤[師]. 𩲈[魏]𢍉[斯],

![]() [趙]

[趙]

![]() [浣], 倝[韓]啟 117/117 章

[浣], 倝[韓]啟 117/117 章

![]() [率]𠂤[師]

[率]𠂤[師]

![]() [救] 赤

[救] 赤

![]() . 楚人豫[舍]回[圍]而還, 與晉𠂤[師]

. 楚人豫[舍]回[圍]而還, 與晉𠂤[師]

![]() [戰]於長城. 楚𠂤[師]亡工[功], 多

[戰]於長城. 楚𠂤[師]亡工[功], 多

![]() [棄]

[棄]

![]() [旃]莫[幕], 肖[宵]

[旃]莫[幕], 肖[宵]

![]() [遯]. 楚以 118/118 與晉固為

[遯]. 楚以 118/118 與晉固為

![]() [怨].ㄴ

[怨].ㄴ

114/114 In the seventh year [422 b.c.e.] of the reign of King Jianda of Chu (r. 428–403 b.c.e.), Lord Dao of Song (r. 421–404 b.c.e.) came to pay court to Chu.Footnote 156 He reported that the Minister of Works of Song, [one unknown character], had severely weakened the ducal house. His Majesty ordered the Mo'ao Yangwei to lead 115/115 the army to settle the ducal house; he built fortifications at Huangchi and at Yongqiu.Footnote 157 Wei Si, Zhao Huan, and Han Qizhang of Jin led their forces to lay siege to Huangchi; after fighting a battle they made them retreat back 116/116 to Chu. In the second year [421 b.c.e.], His Majesty ordered Mo'ao Yangwei to lead the army to invade Jin. He captured Yiyang and laid siege to Chi'an, to avenge the campaign at Huangchi. Wei Si, Zhao Huan and Han Qi 117/117 zhang led their armies to rescue Chi'an, whereupon the Chu army lifted the siege and went home. They fought a battle with the Jin army at the [Chu] Great Wall. The Chu army was not victorious and they had to abandon many of their battle standards and tents, running away under cover of darkness.Footnote 158 Because of this, Chu 118/118 intensified their hatred for Jin.

PERICOPE TWENTY-TWO

119/119 楚聖[聲]𧻚[桓]王即立[位]. 兀[元]年, 晉公止會者[諸]侯於𨙼[任]. 宋

![]() [悼]公𨟻[將]會, 晉公

[悼]公𨟻[將]會, 晉公

![]() [卒]于

[卒]于

![]() . 倝[韓]虔,

. 倝[韓]虔,

![]() [趙]蔖[籍], 𩲈[魏] 120/120 繫[擊]

[趙]蔖[籍], 𩲈[魏] 120/120 繫[擊]

![]() [率]𠂤[師]與戉[越]公殹[翳]伐齊=[齊. 齊]與戉[越]成以建昜[陽]䢹陵之田,

[率]𠂤[師]與戉[越]公殹[翳]伐齊=[齊. 齊]與戉[越]成以建昜[陽]䢹陵之田,

![]() [且]男女服. 戉[越]公與齊侯貣[貸], 魯侯侃[衍] 121/121 明[盟]于魯稷門之外. 戉[越]公内[入], 亯[饗]於魯=[魯. 魯]侯馭[御], 齊侯晶[參]𨌤[乘]以内[入]. 晉𩲈[魏]文侯𢍉[斯]從晉=𠂤=[晉師. 晉師]大戝[敗] 122/122 齊𠂤[師]. 齊𠂤[師]北; 晉𠂤[師]述[逐]之, 内[入]至汧水. 齊人

[且]男女服. 戉[越]公與齊侯貣[貸], 魯侯侃[衍] 121/121 明[盟]于魯稷門之外. 戉[越]公内[入], 亯[饗]於魯=[魯. 魯]侯馭[御], 齊侯晶[參]𨌤[乘]以内[入]. 晉𩲈[魏]文侯𢍉[斯]從晉=𠂤=[晉師. 晉師]大戝[敗] 122/122 齊𠂤[師]. 齊𠂤[師]北; 晉𠂤[師]述[逐]之, 内[入]至汧水. 齊人

![]() [且]又[有]陳𪊵子牛之𥛔[禍]. 齊與晉成. 齊侯 123/123 明[盟]於晉軍. 晉三子之夫=[大夫]内[入]齊, 明[盟]陳和與陳淏於溋門之外. 曰: “母[毋]攸[修]長城; 母[毋]伐

[且]又[有]陳𪊵子牛之𥛔[禍]. 齊與晉成. 齊侯 123/123 明[盟]於晉軍. 晉三子之夫=[大夫]内[入]齊, 明[盟]陳和與陳淏於溋門之外. 曰: “母[毋]攸[修]長城; 母[毋]伐

![]() [廪] 124/124 丘.” 晉公獻齊俘馘於周王, 述[遂]以齊侯貣[貸], 魯侯羴[顯], 宋公畋[田], 衛侯虔, 奠[鄭]白[伯]

[廪] 124/124 丘.” 晉公獻齊俘馘於周王, 述[遂]以齊侯貣[貸], 魯侯羴[顯], 宋公畋[田], 衛侯虔, 奠[鄭]白[伯]

![]() [駘]朝 125/125 周王于周.

[駘]朝 125/125 周王于周.

119/119 When King Shenghuan of Chu (r. 404–401 b.c.e.) was established, in his first year [404 b.c.e.], the lord of Jin met with the other rulers at Ren. Lord Dao of Song was about to meet with the ruler of Jin when the latter died at [unknown placename]. Han Hu, Zhao Ji, and Wei 120/120 Ji led their armies to attack Qi with Yi, Duke of Yue.Footnote 159 Qi made peace with Yue, giving them the fields of Jianyang and Juling, as well as men and women. The duke of Yue performed a blood covenant outside the Ji Gate of Lu, together with Dai, Marquis of Qi (r. 404–391 b.c.e.) and Yan, 121/121 Marquis of Lu (r. 410–377 b.c.e.). The duke of Yue then entered the city to hold a banquet in Lu: the marquis of Lu acted as his charioteer and the marquis of Qi rode beside him in the chariot as they entered the city. Si, Marquis Wen of Wei (r. 445–396 b.c.e.) led the Jin army, and the Jin army inflicted a terrible defeat on the 122/122 Qi army. The Qi army fled northwards and the Jin army pursued them, as far as the Qian River. The people of Qi then suffered the troubles of Chen Qing Ziniu.Footnote 160 Qi made peace with Jin, and the marquis of Qi 123/123 held a blood covenant with the Jin army. Grandees representing the three great families of Jin entered the state of Qi, where they performed a blood covenant outside the Ying Gate with Chen He and Chen Hao.Footnote 161 The agreement said: “Do not repair the Great Wall; do not attack Lin 124/124 qiu.”Footnote 162 The ruler of Jin presented captives from the Qi army and ears to the king of Zhou. Afterwards Dai, Marquis of Qi; Xian, Marquis of Lu; Tian, Duke of Song (r. 403–381 b.c.e.); Qian, Marquis of Wei; and Dai, Earl of Zheng paid court to the 125/125 Zhou king in Zhou.Footnote 163

PERICOPE TWENTY-THREE

126/126 楚聖[聲]𧻚[桓]王立四年, 宋公畋[田], 奠[鄭]白[伯]

![]() [駘]皆朝于楚. 王

[駘]皆朝于楚. 王

![]() [率]宋公以城

[率]宋公以城

![]()

![]() [關], 是[寘]武

[關], 是[寘]武

![]() [陽]. 秦人 127/127 敗晉𠂤[師]於茖[洛]侌[陰], 以為楚

[陽]. 秦人 127/127 敗晉𠂤[師]於茖[洛]侌[陰], 以為楚

![]() [援]. 聖[聲]王即殜[世],

[援]. 聖[聲]王即殜[世],

![]() [悼]折[哲]王即立[位]. 奠[鄭]人

[悼]折[哲]王即立[位]. 奠[鄭]人

![]() [侵]

[侵]

![]()

![]() [關]. 昜[陽]城洹[桓]𢘫[定]君

[關]. 昜[陽]城洹[桓]𢘫[定]君

![]() [率] 128/128 犢

[率] 128/128 犢

![]() [關]之𠂤[師]與上或[國]之𠂤[師]以䢒[交]之, 與之

[關]之𠂤[師]與上或[國]之𠂤[師]以䢒[交]之, 與之

![]() [戰]於珪[桂]陵. 楚𠂤[師]亡工[功]. 兢[景]之賈與

[戰]於珪[桂]陵. 楚𠂤[師]亡工[功]. 兢[景]之賈與

![]() [舒]子共

[舒]子共

![]() [止]而死. 昷[明] 129/129

[止]而死. 昷[明] 129/129

![]() [歲]晉

[歲]晉

![]() 余

余

![]() [率]晉𠂤[師]與奠[鄭]𠂤[師]以内[入]王子定.

[率]晉𠂤[師]與奠[鄭]𠂤[師]以内[入]王子定.

![]() [魯]昜公

[魯]昜公

![]() [率]𠂤[師]以䢒[交]晉=人=[晉人. 晉人]還, 不果内[入]王子. 昷[明]

[率]𠂤[師]以䢒[交]晉=人=[晉人. 晉人]還, 不果内[入]王子. 昷[明]

![]() [歲] 130/130 郎

[歲] 130/130 郎

![]() [莊]坪[平]君

[莊]坪[平]君

![]() [率]𠂤[師]

[率]𠂤[師]

![]() [侵]奠=[鄭. 鄭]皇子=[子, 子]馬, 子池, 子

[侵]奠=[鄭. 鄭]皇子=[子, 子]馬, 子池, 子

![]() [封]子

[封]子

![]() [率]𠂤[師]以䢒[交]楚=人=[楚人. 楚人]涉𣲲[氾]. 𨟻[將]與之

[率]𠂤[師]以䢒[交]楚=人=[楚人. 楚人]涉𣲲[氾]. 𨟻[將]與之

![]() [戰]; 奠[鄭]𠂤[師]逃 131/131 内[入]於蔑. 楚𠂤[師]回[圍]之於

[戰]; 奠[鄭]𠂤[師]逃 131/131 内[入]於蔑. 楚𠂤[師]回[圍]之於

![]() . 𦘔[盡]逾奠[鄭]𠂤[師]與亓[其]四

. 𦘔[盡]逾奠[鄭]𠂤[師]與亓[其]四

![]() [將]軍以

[將]軍以

![]() [歸]於郢. 奠[鄭]大

[歸]於郢. 奠[鄭]大

![]() [宰]

[宰]

![]() [欣]亦𨑓[起]𥛔[禍]於 132/132 奠=[鄭. 鄭]子昜[陽]用滅, 亡𨒥[後]於奠[鄭]. 昷[明]

[欣]亦𨑓[起]𥛔[禍]於 132/132 奠=[鄭. 鄭]子昜[陽]用滅, 亡𨒥[後]於奠[鄭]. 昷[明]

![]() [歲]楚人

[歲]楚人

![]() [歸]奠[鄭]之四𨟻[將]軍與亓[其]萬民於奠[鄭]. 晉人回[圍]𣸁[津], 長陵, 133/133 克之. 王命坪[平]亦[夜]悼武君

[歸]奠[鄭]之四𨟻[將]軍與亓[其]萬民於奠[鄭]. 晉人回[圍]𣸁[津], 長陵, 133/133 克之. 王命坪[平]亦[夜]悼武君

![]() [率]𠂤[師]

[率]𠂤[師]

![]() [侵]晉, 逾

[侵]晉, 逾

![]() [郜],

[郜],

![]() [止]

[止]

![]() 公涉

公涉

![]() 以

以

![]() [歸], 以

[歸], 以

![]() [復]長陵之𠂤[師].

[復]長陵之𠂤[師].

![]() [厭]年倝[韓] 134/134 緅[取], 𩲈[魏]

[厭]年倝[韓] 134/134 緅[取], 𩲈[魏]

![]() [擊]

[擊]

![]() [率]𠂤[師]回[圍]武

[率]𠂤[師]回[圍]武

![]() [陽], 以

[陽], 以

![]() [復]

[復]

![]() [郜]之𠂤[師].

[郜]之𠂤[師].

![]() [魯]昜公

[魯]昜公

![]() [率]𠂤[師]

[率]𠂤[師]

![]() [救]武昜[陽], 與晉𠂤[師]

[救]武昜[陽], 與晉𠂤[師]

![]() [戰]於武昜[陽]之城 135/135 下. 楚𠂤[師]大敗.

[戰]於武昜[陽]之城 135/135 下. 楚𠂤[師]大敗.

![]() [魯]昜公, 坪[平]亦[夜]

[魯]昜公, 坪[平]亦[夜]

![]() [悼]武君, 昜[陽]城洹[桓]𢘫[定]君, 三執珪之君, 與右尹卲[昭]之䇃[竢]死

[悼]武君, 昜[陽]城洹[桓]𢘫[定]君, 三執珪之君, 與右尹卲[昭]之䇃[竢]死

![]() [焉]. 楚人𦘔[盡]

[焉]. 楚人𦘔[盡]

![]() [棄]亓[其] 136/136

[棄]亓[其] 136/136

![]() [旃]幕車兵, 犬

[旃]幕車兵, 犬

![]() [逸]而還. 陳人

[逸]而還. 陳人

![]() [焉]反而内[入]王子定於陳. 楚邦以多亡城. 楚𠂤[師]𨟻[將]

[焉]反而内[入]王子定於陳. 楚邦以多亡城. 楚𠂤[師]𨟻[將]

![]() [救]武昜[陽]. 137/137 王命坪[平]亦[夜]悼武君

[救]武昜[陽]. 137/137 王命坪[平]亦[夜]悼武君

![]() [使]人於齊陳淏求𠂤[師]. 陳疾目

[使]人於齊陳淏求𠂤[師]. 陳疾目

![]() [率]車千𨌤[乘]以從楚𠂤[師]於武昜[陽]. 甲戌, 晉楚以 −/138

[率]車千𨌤[乘]以從楚𠂤[師]於武昜[陽]. 甲戌, 晉楚以 −/138

![]() [戰].

[戰].

![]() [丙]子, 齊𠂤[師]至嵒, 述[遂]還.

[丙]子, 齊𠂤[師]至嵒, 述[遂]還.

126/126 In the fourth year of the reign of King Shenghuan of Chu [401 b.c.e.], Tian, Duke of Song, and Dai, Earl of Zheng, both paid court to Chu. The king led the duke of Song to fortify the Yu Pass and strengthen his position in Wuyang. The people of Qin 127/127 defeated the Jin army at Luoyin, when they came to the assistance of Chu.Footnote 164 King Sheng passed away, and King Daozhe (r. 400–380 b.c.e.) was established.Footnote 165 The earl of Zheng invaded the Yu Pass and Lord Huanding of Yangcheng led the troops 128/128 from Yu Pass and the troops from the Upper States to intercept them, fighting a battle with them at Guiling. The Chu army failed to achieve victory. Jing Zhi Jia and Zigong of Shu were taken prisoner and died. The following 129/129 year [399 b.c.e.], [one partially illegible character] Yu of Jin led the Jin army and the Zheng army to install Prince Ding in power. The duke of Luyang led his army to intercept the people of Jin.Footnote 166 The people of Jin turned back, and thus were unable to install the prince. The following year [398 b.c.e.], 130/130 Lord Zhuangping of Lang led his army to invade Zheng.Footnote 167 Huangzi of Zheng, together with Zima, Zichi, and Zifengzi, led the army to intercept the people of Chu. The people of Chu crossed the Fan [River]. They were just about to fight a battle with them when the Zheng army ran away 131/131 and entered into Mie. The Chu army laid siege to them in Mie, capturing the entire Zheng army and their four generals, returning home with them to Ying.Footnote 168 Chancellor Xin of Zheng then caused a massacre in 132/132 Zheng,Footnote 169 and Ziyang of Zheng's [family] was killed, so that he had no descendants in Zheng.Footnote 170 The following year [397 b.c.e.], the people of Chu returned Zheng's four generals and their people to Zheng. The people of Jin laid siege to Jìn and Changling, 133/133 capturing them. The king ordered Lord Daowu of Pingye to lead an army to invade Jin.Footnote 171 He conquered Gao and arrested Shexian, lord of Teng, returning home with him.Footnote 172 Thus he avenged the campaign of Changling. The year after that [396 b.c.e.] Han 134/134 Qu and Wei Ji led their armies to lay siege to Wuyang, in order to avenge the campaign at Gao. The duke of Luyang led his army to rescue Wuyang, and he fought a battle with the Jin armies below 135/135 the walls of Wuyang. The Chu army suffered a terrible defeat and the three lords who held batons of jade—the duke of Luyang, Lord Daowu of Pingye, Lord Huanding of Yangcheng—died there, together with the Governor of the Right, Zhao Zhi Si.Footnote 173 The people of Chu abandoned their 136/136 battle standards, tents, chariots and weapons, and fled like dogs. The people of Chen then rebelled and installed Prince Ding in Chen. The state of Chu lost a large number of cities because of this. The Chu army was about to rescue Wuyang 137/137 when the king commanded Lord Daowu of Pingye to send someone to request troops from Chen Hao of Qi.Footnote 174 Chen Jimu [of Qi] led one thousand chariots to follow the Chu army to Wuyang. On Jiawu day, Jin and Chu −/138 fought a battle because of this. On Bingzi day, the Qi army arrived at Nie, and then turned back.

* * *

All the stories in Source Text D are dated according to the Chu calendar. The history of the kingdom of Chu in the late Spring and Autumn period and early Warring States era is not well recorded, hence the Xinian may serve to fill this lacuna.Footnote 175 In this respect, the last couple of pericopes in Source Text D are of particular importance, for the information contained here has no equivalent within the transmitted tradition. According to the Shiji, in the chapter on the hereditary house of Chu: “In the eighth year [of the reign of King Jian], Marquis Wen of Wei, Viscount Wu of Han, and Viscount Huan of Zhao were numbered among the lords [of the Central States] for the first time” (八年, 魏文侯, 韓武子, 趙桓子始列為諸侯). This juxtaposition has resulted in a number of scholars suggesting that some event occurred involving the kingdom of Chu which is not recorded within the transmitted textual tradition, which concerns the Three Jins.Footnote 176 Pericope twenty-one of the Xinian describes a successful campaign by the three lords of Zhao, Wei, and Han against Chu during which a couple of major battles were fought. This took place just before Zhao, Wei, and Han were recognized as independent states and it is extremely tempting to see these two events as connected.

The theme of the three lords seeking to establish their authority at the expense of others is then continued in pericope twenty-two, which concerns their campaigns against Qi. Although it is not specifically named in the Xinian, this text appears to make reference to the battle fought at Linqiu in 405 b.c.e., which resulted in an appalling defeat for the Qi army.Footnote 177 The following year was marked by a further major defeat for Qi. As was well understood at the time, the aim was not to overthrow the already deeply unstable regime of Lord Kang of Qi. For the rulers of Han, Wei, and Zhao, the issue was much more straightforward. They needed an excuse to demand that the Zhou king recognize that the state of Jin had collapsed and that their regimes deserved recognition as independent governments. This is quite explicitly stated in the Huainanzi 淮南子 (Book of the Master of Huainan):

三國伐齊, 圍平陸. 括子以報于牛子曰: “三國之地, 不接於我, 逾鄰國而圍平陸, 利不足貪也. 然則求名於我也.”

The three states attacked Qi and laid siege to Pinglu (Pingyin). Kuozi reported this to Niuzi, saying: “The lands of the three states [of Han, Wei, and Zhao] are not contiguous to ours. The profits to be gained by bypassing neighbouring countries and laying siege to Pinglu are hardly worth the effort. The reason that they are doing this is to become famous on the back of us.”Footnote 178