“Questions of ethics and aesthetics, of love and beauty, are intertwined with questions about levees, wetland buffers, and sedimentation rates.”Reference Frodeman, Klein, Mitcham and Tuana 1

Disaster ethics is a developing field of applied ethics that identifies and explores the ethical issues related to disasters.Reference O’Mathúna, Gordijn and Clarke 2 It includes a number of specialized fields, including preventive ethics, ethics of response, and post-disaster ethics.Reference Karadag and Hakan 3 – Reference Zack 4 Preventive ethics, for example, elaborates a set of ethical principles for disaster protocols aimed at preventing disasters, reducing damages or injuries from disasters, and overcoming existing vulnerabilities.Reference Moatty 5 Some preliminary evidence suggests that disaster responders struggle with many ethical issues, yet find few practical guidelines or little useful training. An important step in addressing disaster ethics is to become aware of the ethical issues that can arise in a particular disaster.

This systematic review was designed to identify ethical issues in floods and thereby facilitate the development of relevant guidelines, training, and further research. Floods are increasing in frequency, with the number in Europe more than doubling since 1980.Reference Neslen 6 Globally in 2017, floods were the most common type of disaster (38.4% of all disasters), caused the most disaster-related deaths (35%), and affected most people (59.6%).Reference Wallemacq 7 Extreme precipitation has become more commonplace with massive human and economic consequences.Reference Macpherson and Akpinar-Elci 8 For example, 2 days of heavy rain in 2010 led to €1.2 billion in damages to Dracénie, a small region in southern France.Reference Moatty and Vinet 9 Floods accompany other hazards like hurricanes and cyclones, as when a 1999 severe cyclone in Odisha, India had 10,000 flood-related deaths.Reference Mariaselvam and Gopichandran 10 Floods impact human health strongly, with disease outbreaks occurring short-term, mortality rates in the first year increasing by up to 50%, and psychological distress lasting much longer.Reference Alderman, Turner and Tong 11

All disasters raise ethical issues and questions.Reference O’Mathúna, Gordijn and Clarke 2 , Reference Zack 12 Floods are distinct in relation to ethics because their occurrence and impact are directly tied to human decisions in ways that other disasters, like earthquakes, volcanoes, and hurricanes, often are not. Several examples from the literature reviewed here illustrate this connection, such as when floods are caused by either the deliberate opening of dams or by human decisions that contributed to their failure.Reference Simpson, Cunha and Clegg 13 – Reference Rich 14 The construction of the world’s largest dam, the Three Gorges Dam in China, raised ethical issues because, along with flood management decisions, it displaced 1.3 million people, triggered fatal landslides, and caused environmental problems.Reference Hvistendahl 15 Flooding can be linked less directly to human decisions over deforestation, developing wetlands for economic purposes, or building in flood zones.Reference Chacowry 16 During floods, redirecting excess water toward some communities and away from others raises intense ethical debates.Reference Morss and Wahl 17 For example, rising water levels in 2011 at a dam upstream from Brisbane, Australia led engineers to release water, resulting in US$5 billion in flood damages, the most expensive natural disaster in Australia’s history up to that time.Reference Simpson, Cunha and Clegg 13 Although the decision was based on technical information, ethical judgments were involved also.

Flood risk management is responding to climate change, which raises many ethical questions about how this should be done.Reference Rossano 18 If a flood plan includes permanently displacing a particular community for the good of a larger region, this will provoke many questions, including the ethics of such decisions.Reference Newberry 19 After floods, some may want to demolish flood-damaged buildings and rezone floodplains for other purposes, which means justice must be considered.Reference Jurkiewicz 20 Individual and community perceptions of the good life lead to ethical dilemmas far beyond those of resource allocation. Therefore, responsible social protagonists should understand the profile of the most vulnerable groups in an affected community.Reference Mitrović 21 This is of great importance with floods if the approach promoted is to meet the highest ethical standards.

During disasters, ethics can be perceived and prioritized differently by the impacted community, rescue teams, volunteers, health care professionals, engineers, politicians, and so forth. Ethical dilemmas occur when different professionals engage with different disaster phases, like beforehand during disaster risk reduction (DRR) or flood risk management, or during responses, with triage or recovery. Professionals arrive with different tasks and ethical codes, which can be challenging. Ethical dilemmas arise when concerns about whole populations conflict with individual concerns. How will ethical disagreements be resolved? Does each disaster type need a distinct ethics, leading to, for example, a distinct “flood ethics”? How will ethical principles be applied, or ethical conclusions articulated? These and other concerns motivated this systematic review of ethics and flood to identify how ethical issues are examined in academic literature. The aim was to provide an overview of these ethical issues that makes them easily accessible to those concerned about floods.

METHODS

Data Sources and Retrieval

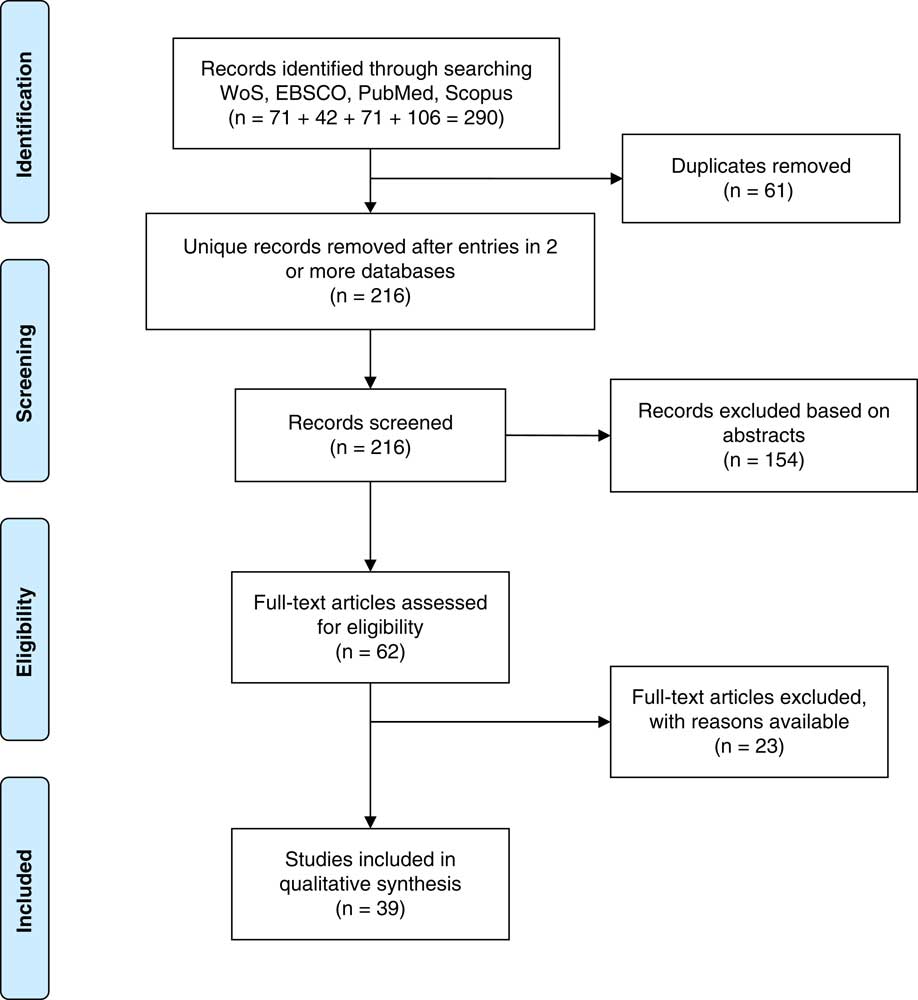

This systematic review aimed to identify relevant studies in the domain of ethical issues in floods. The review methods were guided by the PRISMA Statement on systematic reviews, and the steps involved are shown in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman 22 PRISMA, or Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, is an evidence-based list of the minimum set of items that should be reported in systematic reviews and meta-analyses (http://www.prisma-statement.org). Although the method was developed initially for randomized controlled trials of interventions, it can be used for systematic reviews of other topics. Its guidelines were adapted and followed for this review.

FIGURE 1 PRISMA Flow Diagram for Ethics and Floods.

The first search was performed in March 2015 on three electronic databases: the Web of Science (WoS), PubMed, and EBSCO-SocINDEX databases, including articles from 1955 to 2015. The search terms “ethics” AND “floods” were used on all databases. In April 2018, the search was extended to January 2018. The search terms “ethic*” AND “flood*” were used in PubMed and WoS, which more than doubled the number of identified publications. After examining the abstracts, no additional publications met the inclusion criteria compared with searching with “ethics” AND “floods.” Therefore, the new search was completed with the original search terms. Another database was included in the new search: Scopus, from inception to January 2018. Figure 1 shows the numbers of articles retrieved from each database.

Data Collection

The search returned 290 articles, with the distribution between the four databases shown in Figure 1. Of these, 61 were identified in two or more databases. Removal of the additional entries of the same articles left 216 unique articles. Examination of the abstracts identified 154 articles that did not fit the inclusion criteria described in the next paragraph. The remaining 62 articles were read in full, and a further 23 articles excluded, with reasons for each exclusion recorded. This gave 39 included publications.

Inclusion criteria included any type of publication in the selected databases that examined both floods and ethics in substantial ways. Floods resulting from relatively rapid-onset disasters, such as hurricanes, monsoons, cyclones, and torrential rain, were included, but not those due to gradual flooding, like those accompanying sea-level changes. Publications were included if they addressed ethics before, during, or after floods, and addressed any aspect of flooding, including water management and engineering, public health, flood risk management, preparedness, disaster research, sociological issues, flood responses, and environmental ethics. Articles were excluded if floods were mentioned only as examples within a general discussion of disasters or environmental ethics. Also excluded were articles that discussed floods at length, but mentioned ethics only in passing.

Analysis of Findings

All included articles were uploaded into the qualitative analysis software, NVivo version 11. This software allows identification of “nodes,” each being an ethical issue emerging from the literature. Forty-one nodes were identified and organized into 10 broader themes (see Table 1). The authors discussed the themes iteratively, leading to summaries that revealed the connections between each ethical issue and floods. This analysis is presented in detail in the section, Results.

TABLE 1 Themes from the Analysis of the 39 Included Publications

Note: The total number of publications for each theme does not equal the sum of its subtheme column because publications varied in how many subthemes each discussed.

RESULTS

Scientometric Analysis of the Included Papers

The review included 39 articles published in various academic fields, including biomedicine, social sciences, geophysics, and engineering. They included research studies, editorials, and ethical analyses. The articles addressed floods from around the world, including Australia, the Caribbean, China, Europe, Honduras, India, Japan, Mauritius, Nigeria, Pakistan, Solomon Islands, and the United States, and some addressed floods in general (Table 2).

TABLE 2 Included Articles and Ethical Themes

Qualitative Analysis of Included Articles

Software like NVivo allows some quantitative data to be generated, such as the number of articles addressing each ethical theme (see Table 2). Such analyses have limitations because more frequent discussion of an ethical issue does not necessarily mean that it is more significant. Some articles addressed several ethical issues, whereas others focused on fewer, skewing the numerical count. Some subthemes could fit within different themes, such as the balance between short-term and long-term planning relevant to environmental ethics, flood risk management, and addressing vulnerabilities. In spite of these limitations, such data do show the extent to which various ethical themes are discussed in the academic literature reviewed here. The following are the 10 ethical themes arising from this analysis, arranged alphabetically.

Communication

Communication was identified as critical during floods, with an ethical responsibility to provide information that is “essential, truthful, and useful.”Reference Srinivasan 23 Those with expertise have an ethical duty to inform communications both with the public and those managing flood preparations and responses.Reference Keays 24 Communication should be clear and effective, explaining technical terms well.Reference Keays 24 This benefits others by preparing people for floods and thereby reducing harm and injuries.Reference Gaitonde and Gopichandran 25 Good communication also should convey care and compassion.Reference Simpson, Cunha and Clegg 13

Communication breakdowns have serious consequences, contributing to needless damages and losses,Reference Keays 24 and can contribute to anxiety.Reference Simpson, Cunha and Clegg 13 Poor communication can lead to confusion and conflict between responders.Reference Jurkiewicz 26 Communication addresses more than informational needs and includes balancing the risks of false positives and false negatives due to uncertain information. For example, a record-breaking flood was predicted in 1997 for the Red River in North America, but meteorologists feared panic among the public if worst-case scenarios were discussed.Reference Morss and Wahl 17 What was called “the most overarching informational failure” with Hurricane Katrina was how storm flooding risks were misinterpreted and miscommunicated, leading to a false sense of security about the flood defenses.Reference Newberry 19 Similar problems were identified by the commission investigating the 2010–2011 floods in Queensland, Australia.Reference Ewart and McLean 27

These factors imply that everyone has an ethical responsibility to inform themselves about their flood risks. Creative approaches to communicating flood risks are being developed, like in Munich, Germany, where a public park is allowed to flood regularly as a “vaccine against the illusion of absolute safety.”Reference Rossano 18 Social media is increasingly used during floods to provide rapid communication, although concerns exist about the accuracy of the information provided this wayReference Rizza and Pereira 28 and potential negative effects from identifying flood responders working in insecure settings.Reference Johnston 29

Three subthemes were identified within communication. One was how the ethical principle of autonomy underlies the requirement to provide accurate information and thereby allow decision-makers to make informed decisions.Reference Morss and Wahl 17 The second subtheme addressed community engagement within communication. This related to a paradigm shift within flood risk management from a “top-down” approach to communication, where experts provide information to citizens,Reference Moatty 5 to active engagement between experts and citizens throughout planning.Reference de Groot 30 Authentic collaboration develops trust and allows better communication.Reference Lane 31 Community engagement requires “hard work, sincerity, and honesty,” but is ethically valuable,Reference Parkash 32 especially to identify important local knowledge and cultural values.Reference Moatty and Vinet 9 , Reference Chacowry 16 The third subtheme points to the importance of cultural values in communication.Reference Moatty and Vinet 9 Cultural differences contribute to ethical conflicts, particularly in stressful settings.Reference Malik 33 For example, after Hurricane Katrina, wealthier people measured success in terms of work accomplishments and economic achievements, whereas poorer people measured success through survival and relationships.Reference Jurkiewicz 26 Understanding such cultural values is critical for effective communication in multicultural situations.Reference Holt 34

Environmental Ethics

The literature linked flood ethics with broader concerns about environmental ethics. Human interactions with the environment have been classified as Mastery over nature, Stewardship of nature, Partnership with nature, and Participation in nature.Reference de Groot 30 Similar divergent views are found between Confucianism and Taoism in Chinese cultures.Reference Li, Van Beek and Gijsberg 35 These divergent approaches influence ethical issues, with Mastery emphasizing building dams and dikes to control rivers, while Stewardship holds that control is neither feasible nor good for the environment.Reference Chacowry 16 , Reference de Groot 30 Environmental ethics often overlapped with justice, a separate theme in this analysis.Reference Holt 34 Thus, flood damage from hurricanes in Central America was traced to human decisions that led to deforestation, soil degradation, and chaotic urbanization.Reference Glantz and Jamieson 36 – Reference Hugo 37

Development and sustainability was a subtheme highlighting how emergency flood responses should be balanced with sustainable development.Reference Chacowry 16 Ethical issues arise in determining whether assistance should focus on the immediate needs after floods, or on reducing exposure to future risks.Reference Glantz and Jamieson 36 Preventive ethics is one approach that integrates post-flood recovery programs with measures to reduce flood vulnerabilities and socioeconomic inequalities through building back better.Reference Moatty 5 , Reference Moatty and Vinet 9

Ethical Reflection

Ethical reflection is sound decision-making that ensures the right thing is done for the right reasons.Reference Fahey 38 Flood management requires technical knowledge but is incomplete without ethical knowledge to maximize public goods, minimize flood harms, and make flood mitigation and management systems fair and equitable.Reference Frodeman, Klein, Mitcham and Tuana 1 , Reference Gaitonde and Gopichandran 25 Ethical reflection develops the capacity to act responsibly toward others, particularly the vulnerable.Reference Simpson, Cunha and Clegg 13 , Reference Fahey 38 Some organizations, like the Red Cross, use specific ethical principles to guide ethical reflection that also takes an account of contextual details.Reference Johnston 29 Others advocate the development of ethics guidelines for flood management.Reference Mariaselvam and Gopichandran 10 Cases are used to promote ethical reflection using relevant frameworks.Reference Morss and Wahl 17 Ethical reflection can be complex and messy when undertaken with imperfect knowledge and in the midst of uncertainty.Reference Wildes 39 Professionals who are less familiar with value conflicts may need to develop ethical reflection skills, along with their “moral imagination” and aesthetic sense.Reference Lane 31

Flood Risk Management

Flood risk management covers several aspects of reducing the likelihood and impact of floods. The ethical issues here were frequently raised. Better preparedness was widely held to bring better responses, generating an ethical obligation to prepare well so that communities and facilities become “resilient, responsive, and adequately equipped.”Reference Gaitonde and Gopichandran 25 In contrast, poor flood risk management has harmful consequences,Reference Daniel 40 such as when commercial and bureaucratic interests are placed over individuals’ well-being.Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 Ethical aspects of centralized risk management are rarely addressed because of implicit assumptions over who decides what flood risks are acceptable.Reference Lane 31 The prevailing hierarchical model assumes that risks should be assessed scientifically, that statutory bodies should manage risks, and that those living with flood risks should conform to whatever others decide.Reference Lane 31 This devalues the input of those living with flood risks.Reference Chacowry 16 Involving local communities helps address cultural issues, which can make strategies more effective.Reference Moatty and Vinet 9

The flood risk management theme overlapped with the environmental ethics theme, particularly on whether to fight rivers and control floods, or work with nature.Reference de Groot 30 Management strategies based on mastering nature have been traced to “enthusiasm and faith in the superiority of man’s rationality” 18 and confidence in making regions “climate-proof.”Reference Zegwaard, Petersen and Wester 42 These result in higher risks, with large housing projects throughout Europe built behind river flood defenses on well-known flood-prone areas.Reference Rossano 18 Other management strategies are now being developed based on adapting to flood risk, accepting uncertainty, and rejecting claims of absolute protection from floods.

Uncertainty was a subtheme that characterized flood risk management.Reference Moatty and Vinet 9 Ethical decision-making always involves imperfect knowledge, such as when benefits should be distributed appropriately in light of uncertainty.Reference Morss and Wahl 17 This leads to an ethical obligation to plan with flexibility and allow new information to change plans.Reference Newberry 19 When uncertainty is not communicated adequately, the autonomy and beneficence of those impacted by floods is compromised.Reference Morss and Wahl 17 DRR was another subtheme within flood risk management. When DRR reinforces “command and control” or “top-down” approaches, the public is treated as passive recipients of information rather than active contributors.Reference Chacowry 16 Engaging communities within DRR strategies can reduce flood risks and harms,Reference Moatty 5 such as how Odisha, India, reduced flood fatalities from around 10,000 in 1999 to around 24 in 2013, largely due to introducing DRR systems.Reference Mariaselvam and Gopichandran 10 The ethical obligation to manage floods according to the best available evidence was another subtheme. Poor flood management occurred when manuals and procedures were not updated.Reference Newberry 19 , Reference Ewart and McLean 27 Flood risk management should be science-based but also involves policy decisions that introduce human values.Reference Lane 31 Professionals must also be able to recognize whether various pressures attempt to bias their decisions in unethical ways.Reference Srinivasan 23 The final subtheme here was early warning to reduce harm and preserve life.Reference Chacowry 16 Delayed warnings about Hurricane KatrinaReference Jurkiewicz 20 and the 1997 Red River floodsReference Morss and Wahl 17 caused additional hardship for residents of flooded areas.

Health and Well-Being

Health and well-being was a theme bringing together several related subthemes. The ethical principle of beneficence maximizes benefits over risks and harms and motivates people to help after floods.Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 Flood responders should ask themselves regularly whether their actions are beneficial and to whom.Reference Clark 43 Professional codes of ethics, like those of the American Society of Civil Engineers, emphasize this, stating, “Engineers shall hold paramount the safety, health and welfare of the public.”Reference Daniel 40 Beneficence addresses more than practical utility, because joy can be experienced in the midst of suffering by helpers and those helped.Reference Breo 44 Flood risk management strategies can benefit people and the environment, like when they include recreational areas that promote human well-being.Reference Rossano 18 Social support is an important element of helping people after floods, both for survival and recovery.Reference Chacowry 16 , Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 Beneficence should be based on the needs of those impacted by floods and take into account justice.Reference Moatty 5 Questions must be asked about who benefits and when.Reference Glantz and Jamieson 36 Beneficence not only concerns individuals, but also must address social goods.Reference Morss and Wahl 17 This can lead to ethical dilemmas, like when one area is flooded to reduce the harm to another area, or when present needs are relieved at a cost to future generations.Reference Glantz and Jamieson 36

Another subtheme was harm minimization, with “do no harm” a core ethical obligation.Reference Simpson, Cunha and Clegg 13 Practices that do more harm than good are unethical.Reference Takahashi 45 Harm can occur in many ways, including physically, psychologically, economically, environmentally, socially, and more.Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 Particular attention should be given to those with heightened vulnerabilities and to interventions causing unintended harm.Reference Fahey 38 Difficult ethical dilemmas arise when some people are harmed to reduce others’ harm, as when dam spillways are opened.Reference Simonovic 46

The subtheme, health risks, pointed to an ethical obligation to prepare well for floods. Medical and public health systems should be prepared for disasters, access should be equitable and culturally sensitive, and practice should be evidence-based.Reference Malik 33 When done well, health risks can be reduced.Reference Gaitonde and Gopichandran 25 Floods are particularly challenging with health risks because of displacement, waterborne diseases, release of sewage and pollutants into water, and diminished access to fresh food and water.Reference Macpherson and Akpinar-Elci 8 Justice overlapped here with its concern for vulnerable populations, such as those in wheelchairs, elderly living alone, those with mental illnesses,Reference Gaitonde and Gopichandran 25 and particularly the poor.Reference Srinivasan 23 Safety is related to harm and should be central to flood risk management.Reference Moatty 5 Investigations into Hurricane Katrina have criticized how safety was not a top priority in building levees around New Orleans.Reference Daniel 40 The failure of the Austin Dam in 1911 was largely due to unethical decisions that compromised the dam’s integrity and cost 78 people their lives.Reference Rich 14 In determining how safety is viewed and addressed, both local communities and experts should be involved.Reference de Groot 30

Psychological impacts of flood are significant,Reference Chacowry 16 and the related ethical issues constituted their own subtheme. Posttraumatic stress and depression are commonly found after floods and other disasters.Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 However, many people have mental health and social problems before floods, which may be exacerbated by floods.Reference Breo 44 Ethical dilemmas arise over how to prevent and treat these conditions as evidence is lacking on the effectiveness of interventions, and research on them raises particularly challenging ethical issues.Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 The psychological impacts point to the importance of compassionate support after floods.Reference Simpson, Cunha and Clegg 13 Within this subtheme, 3 factors centered around recovery. Mourning should be permitted, as people experience losses over and over.Reference Botez 47 People should be given time to mourn, including informally by talking to friends and colleagues.Reference Simpson, Cunha and Clegg 13 The second factor was healing, with responders needing to find an ethical balance between remembering and forgetting,Reference Botez 47 because finding positive meaning in the face of floods can be key.Reference Tsu 48 Narratives help here but can be difficult to decipher.Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 The third factor is resilience, or what was called “emotional levees.”Reference Breo 44 Social support and networking are important here, especially in caring for the vulnerable, such as the elderly, disabled, and children.Reference Chacowry 16

A final subtheme mentioned by 2 authors was animal health because of the close connection in some cultures between animal and human health.Reference Gaitonde and Gopichandran 25 Sometimes, animals are part of the family, and people seek help for them after floods. On the other hand, some animal illnesses spread to humans and this should be addressed.Reference Gaitonde and Gopichandran 25 When animals die, the food supply is affected, raising ethical questions about whether they should be rescued or left to die.Reference Macpherson and Akpinar-Elci 8

Justice

Justice linked into many themes as an important ethical principle providing context for balancing benefits and harms, and addressing autonomy.Reference Morss and Wahl 17 , Reference Rizza and Pereira 28 Justice is concerned with fairness, but its practical application is often controversial and disputed. For example, decisions made to allow one region to flood to protect another region on the basis of larger net social benefit are controversial, sometimes leading to civil unrest.Reference Morss and Wahl 17 To minimize these effects, planning and management should be just, needs-based, equitable, and transparent.Reference Gaitonde and Gopichandran 25 In pursuing science-based flood management, a naïve scientism can develop which conflicts with social justice.Reference Lane 31 Even policies to reduce flood-prone housing involve ethical value judgments and are never completely neutral.Reference Moatty 5 According to Rawls’s theory, justice calls for the preferential treatment of the poor.Reference Glantz and Jamieson 36 This is particularly important in research, so that risks and benefits are justly distributed,Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 as it should with the distribution of information.Reference Clark 43

One subtheme here was conflict of interest, where something other than need determines how resources are allocated. For example, a mining company offered a large donation to flood relief in the Solomon Islands, but wanted more funds allocated to regions close to their mines.Reference Johnston 29 The Red Cross determined it would be unethical to accept this donation, partly because those regions were not the most needy.Reference Johnston 29 In 1911, the state senator for the Austin Dam area was also the dam owner’s attorney, setting up another conflict of interest.Reference Rich 14

Injustice was a subtheme identifying ways that resources were distributed unethically.Reference Chacowry 16 Sometimes, relief was deliberately denied certain people, involving discrimination, disrespecting people’s dignity, and potentially violating human rights.Reference Malik 33 Injustice can occur less overtly, as in how those over 75 years made up almost half of the fatalities during Hurricane Katrina.Reference Daniel 40 Similarly, the poor, minorities, and those with mental illnesses suffer disproportionately in flooding.Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 Such vulnerabilities make social justice and ethics discussions crucial with floods.Reference Frodeman, Klein, Mitcham and Tuana 1 Past injustices can contribute to current flooding tragedies. For example, the 1960s deforestation by US-based banana companies left Central America more prone to later hurricane-related flooding.Reference Glantz and Jamieson 36

Another subtheme was preexisting inequalities. Both in high-income countries like the United States,Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 and low-income countries like India,Reference Chacowry 16 the poor suffer disproportionately from flood damage. Sometimes poverty pushes people to live in more flood-prone areas.Reference Hugo 37 The gap between rich and poor nations continues to grow, requiring approaches to justice that actively improve the situations of the more vulnerable.Reference Morss and Wahl 17 Floods can provide opportunities to redress preexisting inequalitiesReference Holt 34 through effective risk reduction and explicit efforts to redress disparities.Reference Moatty and Vinet 9

Addressing limited resources ethically was another subtheme. In building flood defenses around New Orleans, the US Congress sought to minimize costs that impacted safety.Reference Daniel 40 After floods, the need for resources is immense.Reference Johnston 29 Typically, the most ethical approach is to prioritize individuals’ well-being.Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 The resulting ethical dilemmas are intense and make it important to involve local stakeholders in decision-making and policy-making.Reference Moatty 5

Flood insurance was a specific ethical dilemma within justice. Insurance is traditionally based on the view that the burdens of a few should be spread more widely so that more people carry a lighter load.Reference Clark 43 However, as more accurate data on flood risk become available, insurance companies may want to remove high-risk individuals from their client pool. This would leave only lower-risk individuals eligible for flood insurance, but as they understand their risk better, those at low risk will be less likely to purchase insurance.Reference Clark 43 Many do not purchase flood insurance, even when governments urge this, making it unclear how just flood insurance schemes should be created.Reference Morss and Wahl 17

Professional Ethics

This theme combined the ethical obligations of several professional groups involved in floods. Professional ethics are important for credibility, particularly with societal and environmental issues.Reference Parkash 32 When this is lacking, unethical practices undermine recovery and the willingness of others to help.Reference Jurkiewicz 20 Validated competency is an important component of professional ethics.Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 Both scientific rigor and professional ethics are needed for successful water management.Reference Clark 43 The credibility of each profession requires that ethics be addressed diligently and effectively.Reference Parkash 32

Engineering ethics was a prominent subtheme. Engineers’ professional duty to benefit the community comes before their responsibility to the profession or other private interests.Reference Keays 24 The civil engineers’ code of ethics makes public safety and welfare the top priority, although this was found to have been neglected in constructing flood defenses around New Orleans,Reference Daniel 40 and by dam operators in the 2011 Queensland, Australia floods.Reference Ewart and McLean 27 As professionals, engineers need to guard against extrapolating from past experiences into new settings, overlooking their methods’ limitations, and failing to keep current because these all have serious ethical implications.Reference Newberry 19 Some engineers should be involved in politics or with politicians to promote better flood-related policy decisions.Reference Keays 24 Engineers should be aware of the ethical and philosophical debates discussed under the themes of environment ethics and flood risk management because these directly impact on ethical decision-making.Reference Rossano 18 , Reference de Groot 30 , Reference Clark 43 Ethical reflection is key, which is best modeled by mentors who are committed to ethical reflection and practice.Reference Daniel 40

Media ethics was another subtheme. The media can do much good when they disseminate accurate information, but cause harm with biased or sensational stories.Reference Chacowry 16 Selective reporting can bring more attention to one region, with others being neglected, or to an emphasis on short-term relief with long-term development being overlooked.Reference Mariaselvam and Gopichandran 10 The media’s considerable power is seen in how they can attribute blame to individuals or groups.Reference Ewart and McLean 27 During Hurricane Katrina, claims of “civil unrest” and “urban warfare” had little supporting evidence, with the resulting damage difficult to correct.Reference Ewart and McLean 27 On the other hand, media reports of people helping one another can lead to positive community spirit and hope.Reference Simpson, Cunha and Clegg 13

Decisions about flood risk management have political dimensions and point to politicians’ ethical responsibilities.Reference Chacowry 16 Politicians often make ethical decisions about allocating resources.Reference Newberry 19 , Reference Zegwaard, Petersen and Wester 42 However, they can have conflicts of interest, which may influence their decisions unethically.Reference Rich 14 , Reference Jurkiewicz 26 Engagement with local communities and local elected officials is crucial.Reference Moatty 5 The literature included here was mostly critical of politicians. For example, political corruption was a major problem during and after Hurricane Katrina, with authors noting that unethical leadership leads to unethical practices throughout organizations.Reference Jurkiewicz 20 , Reference Holt 34 At the same time, political failures can lead to reform and better policies.Reference Ewart and McLean 27

The professional ethics of scientists impacts how they proceed when data are lacking, or how they allow data to be used or misused by others.Reference Bergstrom 49 Scientists presenting information to the public and policy-makers must make judgments about the risks of false negatives and false positions, which are ultimately ethical decisions.Reference Morss and Wahl 17 Scientists can come under pressure to present their data in ways favoring other interests, giving rise to further ethical dilemmas.Reference Srinivasan 23

The included articles had little to say about health care professional ethics, although this is addressed elsewhere regarding disasters.Reference O’Mathúna, Gordijn and Clarke 2 One included article mentioned the ethics of crisis counseling where professionals encounter problems that exceed their area of specialization and competence.Reference Breo 44 Health care systems have ethical duties to prepare their professionals for floods (by providing appropriate training and resources) and to provide them with mental health services after floods.Reference Gaitonde and Gopichandran 25 In the midst of crises, health care managers make difficult ethical decisions impacting those in their care, for which they often have little guidance and must rely on their consciences.Reference Fahey 38

Research Ethics

This theme arose less frequently than anticipated. Research is needed into the psychological impacts of floods and how to address them, which raises the usual research ethics issues to ensure participants are respected, fully informed, not harmed and recruited justly.Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 Confidentiality is particularly important, suggesting that group interviews are rarely appropriate in psychological research.Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 Even those in powerful positions expect absolute confidentiality in research participation.Reference Jurkiewicz 20 Sometimes, doing research immediately after floods is not ethical because floods deeply impact people who should be allowed to focus on recovery.Reference Moatty and Vinet 9 The data generated by scientific research can lead to ethical debates over ownership and how data should be used beneficially.Reference Bergstrom 49 In general, an ethical responsibility exists to ensure that research results are used practically.Reference Newberry 19

Virtue Ethics

Virtue ethics was a common theme, exemplified by people acting “wisely … and even courageously.”Reference Fahey 38 Virtues engage with questions of conscience,Reference Newberry 19 such as when the virtue of courage leads someone to speak the truth even with negative consequences.Reference Rich 14 The literature often criticized those lacking certain virtues, such as when people took advantage of distressful situations for personal gain.Reference Jurkiewicz 20 Altruism was a virtue one author claimed was rarely visible in today’s leaders, leading to questions about how this and other virtues could be nurtured.Reference Macpherson and Akpinar-Elci 8 Seeing people act virtuously, as when they are compassionate, can motivate others to follow that example.Reference Simpson, Cunha and Clegg 13 Virtue ethics uses narratives to instill virtues, providing one means of transforming horrible flood narratives into something encouraging.Reference Tsu 48

Each subtheme here focused on a specific virtue. Compassion was defined as the “capacity to act responsibly toward the ‘other’” and viewed as central to all ethical decision-making.Reference Simpson, Cunha and Clegg 13 Courage helps people act on their belief that peoples’ well-being should be prioritized.Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 For example, a Brisbane branch of an international company broke with its policy of not paying employees who could not work during the 2011 Brisbane flood, demonstrating compassion and moral courage.Reference Simpson, Cunha and Clegg 13

Honesty was the most frequently mentioned virtue and included admitting when interventions and policies do not work because this avoids wasting resources.Reference Bergstrom 49 Honest appraisals of flood risks help avoid false expectations.Reference Morss and Wahl 17 Honesty is crucial to maintain credibility.Reference Parkash 32 Impartiality is an aspect of honesty where people commit to make judgments based on evidence and needs.Reference Simonovic 46 Thus, impartiality is a core ethical principle for the Red Cross, where anything that compromises the perception of impartiality is viewed as unethical.Reference Johnston 29 Dishonest reporting can lead to harm, as was noted under media ethics.Reference Ewart and McLean 27 Failing to fulfill commitments, sometimes called donor fatigue, also can reflect a lack of honesty.Reference Glantz and Jamieson 36 After Hurricane Katrina, harm arising from dishonesty was identified, including individuals filing false damage claims, contractors taking money without doing the work, and politicians being unable to account for funds.Reference Jurkiewicz 20

Humility was an important virtue, especially when working with unknowns and uncertainties, and for admitting when approaches do not work.Reference Parkash 32 , Reference Bergstrom 49 The change in attitude toward nature from one of mastery to cooperation expresses humility.Reference de Groot 30 This involves dismissing the “myth of absolute protection.”Reference Rossano 18 Humility links with honesty in that open communication of experiences can invoke humility and gratitude, leading to generosity toward others.Reference Simpson, Cunha and Clegg 13

Respect for others was another ethical virtue. The Red Cross’s ethical code is based on the view that all humans are of equal worth and that everyone has a duty to help those in need.Reference Johnston 29 Similarly, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that all humans have “inherent dignity” and “inalienable rights.”Reference Malik 33 This should lead to people developing the virtues of respecting othersReference Simonovic 46 and valuing their dignity.Reference Simpson, Cunha and Clegg 13

The virtue of transparency promotes fairness and accountability.Reference Gaitonde and Gopichandran 25 , Reference Johnston 29 It leads to openness about the uncertainty of some information in flood planning, and the importance of impartial decision-makers.Reference Simonovic 46 Transparency is important in ethical decisions, especially when people hold different positions, and points to why people should be able to explain the reasons why certain decisions were taken.Reference Wildes 39

A core element of virtue ethics is trust, which can be difficult to win.Reference Breo 44 When authorities are believed to lack core virtues, people’s trust quickly disappears.Reference Chacowry 16 In contrast, trust is won through a history of virtuous behavior.Reference Johnston 29 It is gained by working together and sharing common experiences.Reference Lane 31 During crises, trust must be nurtured, for which good communication and empowering community members are important.Reference Rizza and Pereira 28

Vulnerability

The final theme was vulnerability, giving an ethical obligation to care for those at particularly high risk of harm from floods.Reference Chacowry 16 Heightened vulnerability arises for those over 75 years, minorities, the poor, and those with mental illnesses.Reference Mariaselvam and Gopichandran 10 , Reference Daniel 40 – Reference Dennis, Kunkel, Woods and Schrodt 41 Those requiring wheelchairs and other medical equipment are more vulnerable during floods, as are residents in jails, orphanages, and other institutions.Reference Gaitonde and Gopichandran 25 A complex interplay of social, economic, and natural causes increases or decreases vulnerabilities.Reference Frodeman, Klein, Mitcham and Tuana 1 Yet, in some situations, the vulnerable are actively discriminated against.Reference Mariaselvam and Gopichandran 10 This should be seen as unethical, and active steps taken to overcome vulnerabilities.Reference Morss and Wahl 17 Recovery periods can be used as opportunities to address inequities and overcome vulnerabilities, and this should be an ethical priority.Reference Moatty 5

A subtheme here was concern for refugees. Floods and other disasters lead to many internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees.Reference Glantz and Jamieson 36 Environmental changes traditionally led to IDPs who remained within their countries, as when mass migration into cities occurred after one-fifth of China’s uplands were flooded in 1994.Reference Hugo 37 In 2010, heavy rainfall led to record flooding in Pakistan, which killed almost 2,000 people, impacted 18 million, and led to millions of IDPs.Reference Malik 33 However, the scale of floods is leading to increased numbers of refugees crossing borders, for which many regions are unprepared.Reference Glantz and Jamieson 36 Migrants and refugees often live in insecure housing which makes them particularly vulnerable to further harm.Reference Mariaselvam and Gopichandran 10 Yet, in many places, no provisions are made for migrants and local officials who may not know how many live in their jurisdictions. This adds an ethical responsibility to include migrants in flood risk management plans.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review identified 39 included articles addressing ethics in floods. Their analysis led to 10 ethical themes and several subthemes. Some themes, like justice and professional ethics, had been anticipated, but others had not been expected to feature as prominently, like virtue ethics and animal ethics. Some ethical issues were discussed less frequently than anticipated, as with research ethics and health care ethics, although these are discussed elsewhere for disasters generally.Reference O’Mathúna, Gordijn and Clarke 2 , Reference Mezinska, Kakuk and Mijaljica 50

Social justice was a broad area of ethical concern, emerging in 25 of the 39 included articles. This theme was identified as strongly influencing other ethical themes. Comparative studies have shown that the same flood has different impacts within the affected population based on varying levels of resilience.Reference Zack 51 – Reference Lewis 52 This capacity is related to social inequality, vulnerability, and susceptibility within societies.Reference Barton 53 The enormous economic and human toll of floods alerts us to the need to constantly develop and reevaluate ethical guidelines. Disasters trigger an emphasis on promoting better survival rates and quicker recoveries. However, mere survival is usually not enough for those who live directly with the consequences of floods and disasters. Recovery that focuses only on the built environment could inadvertently lead to undesirable outcomes or unethical means to goals, especially for those with preexisting inequalities. Rebuilding flooded areas to restore pre-flood conditions is not as beneficial as building back better. Doing so requires careful reflection on ethical issues, and ethical guidelines should take into account the resilience and vulnerability of different groups within society. The dignity and equal rights of all should be recognized and protected in flood-prone societies.

Many articles called for increased training in ethical reflection and decision-making for the various professionals working on floods. The goal, according to one included article, seems simple: Do the right thing. Reference Fahey 38 Achieving this is not so simple. “Specifically, morally sound decisions involve good information, sound values, engagement of appropriate stakeholders, and the ability to make decisions. Seeking morally sound decisions is complex because situations often require decisions by a group (underpinned by individual decisions). These are made in the fog of incomplete or contradictory information by people applying different weights to sometimes competing values.”Reference Fahey 38 This makes ethics in floods complicated and challenging. Gathering and organizing the ethical issues in this review here is one step toward linking the existing social and economic inequalities, vulnerabilities, and resilience with planning and actions that can prevent or reduce the costs, harms, and numbers of victims in floods.Reference Mitrović 21 The way forward is challenging, but the alternative is less attractive because “ethically unsound decisions can produce disastrous results not only for those already living in precarious situations, but also for those endeavoring to assist them.”Reference Johnston 29 Further conceptual analysis can help clarify the ethical issues, but such research must lead to clear and practical guidance and decision-making tools. Our hope is that this review will alert readers to the intimate link between ethics and floods, and stimulate further scholarship and practical action on this topic.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review had limitations. The search was restricted to 4 electronic databases, which included academic literature primarily, although from a wide variety of fields. Grey literature was not searched, which could provide relevant material from international organizations (like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC] or the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction [UNISDR]) and nongovernmental organizations. Likewise, news media and books were not reviewed. Additional or different ethical issues might be discussed outside of academic sources. However, the scale of such a broad search went beyond the resources available for this review. Another limitation was that most publications were qualitative and presented personal views as opposed to empirical studies. This prevents any clear conclusions about the scale of ethical issues and the extent of their impact. Such studies should be undertaken to better understand these dimensions. In addition, the qualitative nature of this review’s analysis means that the authors’ professional and personal orientations may have influenced the selection of articles and the identification and classification of themes and subthemes. Such limitations are inherent to this type of research, and mean that caution is required in generalizing any of the findings.

Nonetheless, this systematic review reveals a wide variety of ethical issues and situations in floods. The results have implications for those involved in DRR and flood risk management, showing that ethical issues should be considered carefully in planning for and responding to floods. Given the variety of ethical issues identified, an interdisciplinary approach is required to ensure that ethics is considered at all stages of flood planning and responding. Research is needed into the scale and experience of ethical issues in floods, so that evidence-based approaches to ethics in floods are developed and implemented. Only then can some assurance be provided that floods are addressed in the right way at the right time.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of COST Action IS1201: Disaster Bioethics (http://DisasterBioethics.eu), which funded short-term scientific missions (STSMs) at the Universities of Zagreb and Belgrade and attendance at Action events where this paper was developed.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.