INTRODUCTION

While there are accepted triage and treatment guidelines for the entrapped and mangled extremity in civilian and military resource rich environments (RRE), there are none for resource scarce environments (RSE).

In 2002, Feliciano and the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma Subcommittee on Publications published the Management of the Mangled Extremity.Reference Feliciano1 This was not intended to “be comprehensive nor a standard of care” given the unique patient presentations in which the guidelines may be used.Reference Feliciano1 The definition of the mangled extremity is applicable regardless of setting, though the causes may be different with different high-energy transfer in the varied RSE. The injury patterns of military gunshot wounds are more devastating than the close-range shotgun wounds encountered in civilian environments. Similarly, blast injuries were rarely encountered in civilian environments as terror attacks have increased over time. The decisions for the treatment team remain, without altering standard of care in an RSE.Reference Schultz and Annas2

In 2012, the Western Trauma Association (WTA) created a treatment algorithm “Management of the Mangled Extremity” placing persistent hemorrhage or refractory hemodynamic instability as the second decision to make after control of active hemorrhage.Reference Scalea, DuBose and Moore3 The majority of RSE settings will not have the opportunity to use computed tomography angiography imaging nor have the surgical staff with sufficient training and supplies to place an intraluminal shunt.

A systematic literature review (SLR) was performed to elucidate the current triage and treatment of an entrapped or mangled extremity in resource scarce (civilian and military) environments. Further analysis as a component of this practice was to understand the factors contributing to the decision to amputate or not amputate, to determine the incorporation of rehabilitation and social services, and the informed consent process.

Based on these studies, 49 data points could be considered for consensus ethical triage and treatment guidelines of the entrapped and mangled extremity. The RSE presents unique challenges to evaluate and treat a mangled extremity, specifically without evidence-based assessment and treatment guidelines. This SLR can begin the process of adapting and modifying current civilian and military guidelines to the RSE.

METHODS

English language studies published between January 1985 and March 2017 were retrieved for inclusion in agreement with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement. The search strategy was designed to capture data reporting in an RSE: after a sudden-onset disaster, in a complex humanitarian emergency, in a conflict area, in a low-to-middle income country, or with long transport times. Unique criteria considered included those specific to certain mechanisms of injury, subsequent procedures, and those data points used in validated mangled extremity evaluation and treatment scoring systems. These points were sought to maintain a consistent approach comparing environments under the direction of an experienced Informationist (TH) to comply with the PRISMA guidelines4 (Table 1). The databases were selected to ensure a comprehensive cull of available publications; references of selected articles were retrieved and considered in this SLR (Table 2).

TABLE 1 Search Strategy

TABLE 2 Database Searched

ManageMe LLC (Toms River, NJ) was contracted to develop the data extraction tool combining evidence-based practice strategy, as well as content data. This Excel spreadsheet construct featured dropdowns to sort information for that specific question or to guide the reviewer to the next step. The initial section contained the demographics of the article and characteristics of article type, followed by inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 3). The next section included data points to assist the reviewer in answering the question, “Does this evidence address my evidence-based practice question, to determine triage and treatment guidelines of the entrapped and mangled extremity in resource scarce environments?”

TABLE 3 Criteria for Study Inclusion and Exclusion

The 2 lead researchers (EW, JG) divided the articles that met inclusion criteria into 6 randomly assigned groups by a single 6-sided dice roll. EndNoteX8 was used to collect the references and articles. A reviewer trained in this SLR process and a lead researcher were paired and assigned to each group to provide 2 independent reviews of level of evidence (LOE), quality of evidence (QE), and data points for each article.

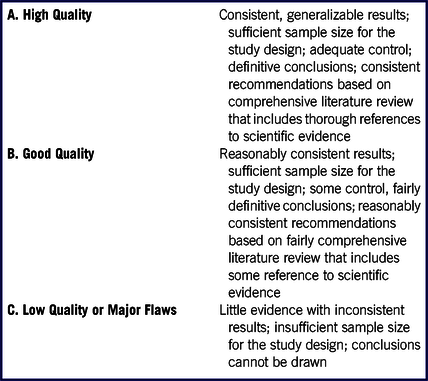

The LOE data points were acquired with opportunities for the reviewer to note specific findings that would aid the creation of a triage and treatment guideline based on the SLR (Table 4). Then the QE was ranked by “high (1) – good (2) – low (3)” by the reviewers. These sections featured the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Research and Non-Research Evidence Appraisal questions for their ease of use and understandingReference Newhouse, Dearholt and Poe5 (Table 5). The widely accepted Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for case control and cohort studies was followed for these types of studies.6 In an effort to determine bias, the next sheet asked the reviewer to use the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool.7

TABLE 4 Level of EvidenceReference Newhouse, Dearholt and Poe5

TABLE 5 Quality of EvidenceReference Newhouse, Dearholt and Poe5

Clinical data used in various triage and treatment guidelines were captured from an article’s study of the entrapped and mangled extremity recordingReference Brown, Ramasamy and McLeod15 core clinical parameters that formed the basis of most studies (Table 6). Fourteen injuries and procedures were selected in order to compare similar studies (Table 7). The RSE radiology imaging presents a challenge to adopt or adapt triage and treatment guidelines from RRE escalating from plain imaging to fluoroscopy to assess bony injury and non-invasive Doppler/ultrasound to contrast angiography to assess vascular injury. The care setting discussed in each article was recorded for each RSE. The treatment of the mangled extremity includes rehabilitation services without altering the standard of care in an RSE. Data regarding prosthetics, orthotics, physical and occupational therapies, and community integration were sought to determine whether these were included in the reports. The other parameters noted involved ethics: informed consent; involvement of family, patient advocate, or community leader; and the religious or ethnic preference discussed.

TABLE 6 Clinical Parameters

TABLE 7 Injury Pattern or Procedure

A lead researcher (EW) received the 12 final data sheets (6 groups × 2 reviewers each) to determine any data point disagreement between the 2 assigned reviewers, specifically, the LOE because only LOE 1–3 were included in the final analysis. Any disagreement was discussed amongst the 2 reviewers to reach consensus. If consensus was not met, then the lead researcher (EW or JG) who was not 1 of the 2 reviewers of that article was asked to arbitrate, discussing the article with the reviewers until a consensus was met. A third set of 6 data sheets was created reflecting consensus data and sent to ManageMe to concatenate the 6 sheets into 1. csv file to prepare for statistical analysis by MedStatStudio (Edmonton, Alberta, Canada).

The complete data extraction tool is available upon request.

This study was a literature review and did not involve human subjects and is registered PROSPERO 2017:CRD42017052015.

RESULTS

Summary of Literature Reviewed

The initial total number of references obtained was 597, and, after removal of duplicates, abstracts, non-English, or other exclusion criteria, 297 were entered into the review process (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 PRISMA Flow.

Table 8 shows the 58 articles that were entered into the final SLR study, with 46 single studies, 11 multiple studies, and 21 with control groups. There was 1 study determined to be LOE 18, 29 LOE 2Reference Akula Maheswara9-Reference Tufescu and Bhandari37, and 28 LOE 3Reference Agarwal, Agarwal and Singh38-Reference Yeh, Fang and Lin64, with 15 determined to achieve QE 1Reference Ly, Travison and Castillo8,Reference Bortolin, Morelli and Voskanyan11,Reference Bosse, McCarthy and Jones14,Reference Demiralp, Ege and Kose16,Reference Elsharawy18,Reference Loja, Sammann and DuBose24,Reference Lynch and Johansen25,Reference Perkins, Yet and Glasgow31,Reference Burkhardt, Cox and Clouse43,Reference Dagum, Best and Schemitsch44,Reference De Silva, Ubayasiri, Weerasinghe and Wijeyaratne46,Reference Doucet, Galarneau and Potenza48,Reference Fortuna50,Reference Kauvar, Sarfati and Kraiss55,Reference Yavuz, Demirtas and Caliskan63,Reference Jensen, Bar-On and Wiedler65 , 37 QE 2Reference Akula Maheswara9,Reference Bonanni, Rhodes and Lucke10,Reference Bosse, MacKenzie and Kellam12,Reference Bosse, MacKenzie and Kellam13,Reference Brown, Ramasamy and McLeod15,Reference Ellington, Bosse, Castillo and MacKenzie17,Reference Essa, El-Shaboury and El-Beltagy19,Reference Gifford, Aidinian and Clouse21,Reference MacKenzie, Bosse and Kellam26-Reference Niles, Polizzi and Voelkel30,Reference Rajasekaran, Naresh Babu and Dheenadhayalan32-Reference Brown, Murray and Clasper42,Reference Delauche, Blackwell and Le Perff47,Reference Ege, Unlu and Tas49,Reference Gerdin, Wladis and von Schreeb51,Reference Harris, Althausen and Kellam52,Reference O’Sullivan, O’Sullivan and Pasha56-Reference Wuthisuthimethawee, Lindquist and Sandler62,Reference Yeh, Fang and Lin64,Reference Ladlow, Philip and Coppack66 , and 6 QE 3Reference Fagelman, Epps and Rang20,Reference Helfet, Howey, Sanders and Johansen22,Reference Khan, Amatya and Gosney23,Reference De Freitas Valeiro Garcia, de Sá, de Oliveira Bernini and Rasslan45,Reference Hossny53,Reference Johansen, Daines and Howey54 .

TABLE 8 Level and Quality of Evidence Results

Parameters (#of Articles)

The parameters were selected as general categories to assist the analysis of LOE and QE, not for detailed analysis of the individual clinical parameter, as this would be an entirely different SLR. The data are presented as the total number of articles (# of articles) for the reader to appreciate the number of articles that the parameter is mentioned out of the selected total number of articles that met inclusion criteria.

Clinical Parameters

Fifteen clinical data points, including the time of injury (29), duration of ischemia (31), assessment of circulation (42), wound contamination (24), and limb function (25), were reported; standard fundamental history and physical data points should be included in the triage and treatment calculus of any injury in any environment. Similarly, documentation of clinical findings included in widely accepted mangled extremity scoring systems requires the reporting of an arterial (40), venous (30), nerve (42), or skeletal (37) injury. The Gustillo classification of open extremity fractures requires reporting if the injury was over a fracture (32) or involved periosteal stripping (24). (See Table 6.)

Injury Patterns or Procedures

There were only 9 articles from this SLR discussing the triage and treatment of the entrapped mangled extremity at the scene. Either at the scene or at definitive care, the general acceptance of converting a skin bridge, a near complete amputation with only a small portion of skin intact with complete neurovascular and bone destruction to a complete amputation, was noted in 16 articles. Specific operative procedures of primary amputation (47), staged debridement (33), damage control surgery (36), fasciotomy (24), closed reduction (12), internal fixation (15), external fixation (24), and stump revision (12) were collected. (See Table 7.)

Imaging

Studies with the ideal of angiography (16) and fluoroscopy (3) to the common plain (16) and increasingly RSE-viable non-invasive (15) modalities were noted.

Medications

There was reporting of general (27), local (4), and regional (3) anesthesia articles with 9 reporting analgesia and 26 reporting antibiotics.

Clinical Setting

In this SLR, the overwhelming majority of studies (53) were conducted in fixed medical facilities. There were studies from alternative care sites (9) such as tents, in the open air or non-medical structures and non-medical fixed structures (8) sources. Sources of studies came from Disaster Medical Assistance Teams (9), World Health Organization (WHO) Emergency Medical Teams (EMTs) (21), the WHO (20), non-WHO research centers (12) like Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), government organizations (GOs) (18), and non-government organizations (non-GOs) (10).

Rehabilitation

Data were recorded to learn whether specific aspects of the WHO Minimum Technical Standards and Recommendations for Rehabilitation were reported.67 This standard was referenced in this SLR with prosthetics (8), orthotics (9), occupational therapy (14), physical therapy (16), and community integration (11).

Ethics

Data were also recorded to learn whether the WHO Minimum Standards for (Foreign) EMTs regarding informed consent and ethical considerations was reported before and after this publication.Reference Norton, von Schreeb and Aitken68 This was mentioned in 8 articles with family (3), patient advocate or community leader (1) participating on behalf of or assisting the patient. Only 2 articles made specific mention of religious or ethnic preference that guided treatment of the entrapped and mangled extremity.

Final data sheets are available upon request.

LIMITATIONS

There may be consequential non-English articles that were beyond our collective capabilities. Despite our attempts to capture relevant articles through gray literature (non-scientific or non-peer-reviewed journals and lay press) and a process to “follow the breadcrumbs” (retrieving references cited in articles), there may have been relevant articles that were not secured.

This study ended in 2017 and was submitted for publication in 2019. It is possible that there were other published studies that could have influenced the results. The use of SLR tools to determine level, QE, risk of bias, case control, and cohort studies reflects what was available during the time frame of the SLR; in the end, the change between versions is debatable in the context of this SLR.

DISCUSSION

The publication of “The Management of Limb Injuries During Conflicts and Disasters” by the WHO EMT Secretariat, ICRC, and the AO Foundation in 2015 continued the discussion of triage and treatment of the entrapped or mangled extremity in Chapter 10, “Amputations.”69 Their (WHO EMT) appeal for a multi-dimensional process as constructed in the WTA is based on lessons learned in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. This SLR did find evidence that the general principles of definitive amputation espoused in this management publication were evident in line with the WTA that called for utilization of an intraluminal shunt. In the absence of vascular reconstructive capabilities, an amputation is indicated with an avascular limb. It becomes incumbent on the RSE treatment team to be aware of what reconstructive resources are at their disposal in the immediate, short, and long term to enhance the decision process to delay care toward limb salvage.

Jensen et al., in 2019, wrote that “the group (the authors) states that no amputation should be done immediately” yet this SLR did not find evidence to support this absolute statement when there are scenarios in a RSE that would place the patient’s life in jeopardy.Reference Jensen, Bar-On and Wiedler65 The timeline of injury to patient presentation in some RSEs is difficult to determine as patients may have to be extricated, transported, and then wait for initial and then definitive treatment. This timeline is of course needed to calculate whether the warm ischemia time or arterial occlusion is greater than 6 hours.Reference Johansen, Daines and Howey54

More pressing is the determination of arterial insufficiency while the extremity is still entrapped as the rescue team does not know the status of the extremity on the other side of the entrapment unless structural assessment can conclusively determine otherwise and the rescue team is in agreement. This SLR was unable to find a triage and treatment guideline or study examining this decision process, leaving the rescuers to base their decision to amputate or not on non-physiologic parameters. Certainly, if there is an imminent risk to the patient or the rescuers, an amputation must be performed to save the life of the patient and/or the rescuer(s). An absolute indication for amputation of the entrapped extremity is when there is immediate and real risk to the patient’s life and those of the rescuers, when the scene is currently safe for the rescuers to enter, but the environment or the scene is deteriorating and time is of the essence.

This SLR was also unable to find a triage and treatment guideline or clinical study that examined whether clinical response to field therapy is factored into the decision to save a life over saving the limb. Although, it seems reasonable to seriously consider amputation of the entrapped extremity when the patient is physiologically unstable, when the patient is not responding to IV fluid (persisting hypotension), and/or there is the inability to maintain adequate oxygenation or other resuscitation measures due to occult blood loss or other injuries, and/or there is a lengthy extrication with perhaps greater than 6 hours total crush time (6 hours of ischemia). As a team with involvement of the patient (and their family if available), without reasonable scientific studies to provide a triage and treatment guideline, rescuers are left with the overriding question to answer before a field amputation, “Without the ability to extricate the patient, without performing a field amputation, will this patient surely die?”

The inconsistency in data reporting for physical exam findings, imaging, and operative findings may be a reflection of the specific research and/or a result of the lack of medical record keeping and falling below the accepted standard in the RRE in most countries. The authors accept that some studies were not specifically structured to incorporate physical examination findings and to wit the data extraction tool was limited to earmarking those studies. Data points were chosen to reflect those included in the many-mangled extremity scoring systems and, regardless of their validity or accuracy, these physical findings are pertinent in any environment to determine further evaluation and treatment.

Criteria from the WTA were incorporated into this study. The only step in the flow that would probably not be available in an RSE is a computed tomographic angiogram to provide imaging of the arterial injuries and reconstituted flow distal to the wound. The diagnostic resources available in an RSE triage and treatment guideline should consider that the RSE is without readily available computerized axial tomography scans, arteriography, and potentially without ultrasonography or plain X-rays even for a few patients, much less a mass casualty incident.

The key to extrapolating or adapting the imaging information used to guide the treatment of the mangled extremity from an RRE to an RSE is to understand the limitations or lack of imaging in the RSE ranging from scarce or unreliable electricity, equipment, and operators. After physician examination, arterial integrity is an important decision point and can be determined using a Doppler examination, or a handheld ultrasound probe using a smart phone, potentially available in an RSE. The use of scoring systems since 2002 has been shown to be useful to some extent but not to guide management as these guidelines imply. Therefore, future studies could investigate other modalities, such as ankle-brachial index and ultrasound, that were shown in this study.

Damage control surgery in the RSE can be modeled after the military environment where in-theater intravascular shunts have been shown to salvage the mangled extremity.Reference Taller, Kamdar and Greene60 Specific training and maintenance of competency of the general surgeon to perform this procedure in an RSE were shown to be effective, raising the potential for training of humanitarian surgeons in other RSEs.Reference Wong, Trelles and Dominguez70

The WTA calls for classification of the bony injury that was not shown to be consistent in this SLR but can be made mandatory through education and a designed medical record that specifically records these parameters. Proper charting of the patient encounter with a mangled extremity, albeit curtailed after a mass casualty incident or in certain RSE, is to permit the treating physicians to be able to provide a more “comprehensive evaluation of systematic consequences of limb salvage attempt” when discussing treatment options with the patient, their family, or representative in the informed consent process.Reference Scalea, DuBose and Moore3

The WTA algorithm’s detail at the final stages of the limb salvage decision process was not found in the SLR. Certainly, one can offer that proper expedient decisions were made using a collaborative process involving the full treatment team, the patient, or their representatives to assure that the informed consent process was maintained and that after care was incorporated. But the standard in civilian, military, and most RREs is that the medical record details the history, physical exam, ancillary testing, as well as the discussions and future plans. This SLR did not encounter consistent documentation of this process.

Future triage and treatment guidelines should feature the patient’s perspective from the earliest juncture in that patient’s clinical course. International response teams working with the local government health authority and the WHO Global Health Cluster should work together to align triage and treatment guidelines with patient and family expectations.

Unfortunately, this may not have been the usual as reported in a follow-up study of amputees after the 2010 Haiti earthquake demonstrated that 79% would have preferred limb preservation.Reference Feliciano1 In their 2015 United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) Scientific and Technical Advisory Group case study, “Ethical dilemmas with amputations after earthquakes,” O’Mathúna and von Schreeb succinctly described the challenges facing responders.Reference O’Mathuna and von Schreeb71 This study confirmed the large number of ethical and clinical variables that must be in the evolving RSE physician calculus.

As future experts create triage and treatment guidelines of the entrapped and mangled extremity in the RSE, the consideration of the setting may be paramount to guide an algorithmic approach with appropriate staff, supplies, and structure to provide the means to the best possible clinical outcome. This may be because incidents that occur and are treated in remote, mobile facilities do not have these resources. The study of these settings may also lack for proper scientific data collection, further hindering application of triage and treatment guidelines in RSEs.

The treatment of an entrapped and mangled extremity in an RSE is a team effort with the depth of after-care planning initiated in concert with the technical aspects of the procedure to return the patient to the highest level of function and health. These data are encouraging because the majority of studies were published before the WHO Rehabilitation document. The informed consent process, present in civilian and military settings and advocated by the WHO and others, may be difficult in any emergent setting with provisions that meet jurisdiction, religious, and ethnic considerations to meet the standard for the patient to participate in their care.

The standard of care in an RSE remains paramount with the challenge to do the most good for the most people. Many supervisory, regulatory, and other GOs and non-GOs have produced anesthesia, analgesia, and antibiotic recommendations to treat the injured in the RSE to establish an expectation of care. Because some of the studies in the SLR were not specifically designed to examine use of medications, the data tool asked only whether classes of medications were discussed without delving into the specific indications or dosages of any medication. The authors were interested to learn whether recommendations were incorporated into clinical practice and reported accordingly.

CONCLUSION

The subject matter, triage, and treatment of the entrapped or mangled extremity in RSE were proven again to not lend itself to a formal PRISMA SLR that is designed for a more concrete treatment data analysis (eg, pharmacologic options) from more consistent environments (RRE) with more consistent documentation. Data captured can add to the body of available literature to convene the best scientific analysis to produce consensus clinical treatment guidelines through a Delphi process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professors Francesco Della Corte, Skip Burkle, Lisa Kurland, and Ahmadreza Djalali for their contributions to this study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.