As health professionals, dentists are in the front line and have a high risk of contracting infectious diseases, which can be transmitted by direct or indirect contact through instruments or body fluids, such as blood and saliva. Reference Xerez, Neto and Lopes1 Therefore, dentists must comply with biosafety standards to protect both themselves and their patients. Reference Uramis, Peña and Perez2 Safety in dental care should be similar for all patients and not only for those with infectious diseases. Operators and patients may be potential asymptomatic carriers of different microorganisms, causing cross-infections that can affect anyone in dental care and that can be transmitted to the family environment, increasing the risk of contagion. Reference Barbieri, Feitosa and Ramos3

On December 31, 2019, the authorities of Wuhan, China, notified the World Health Organization (WHO) of the presence of an outbreak of viral pneumonia of unknown origin, mainly among vendors or operators of the Marine Huanan food market. Reference Rodríguez, Sánchez and Hernández4-Reference Zhu, Zhang and Wang6 Within a few days the disease was called coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2 virus, which is transmitted mainly by close contact with secretions or excretions (droplets) of infected patients in the absence of the necessary protective barriers. Reference Gallasch, Cunha and Pereira7 Thus, COVID-19 spread rapidly to different parts of the world, and on March 11, 2020, COVID-19 was categorized as a global pandemic by the WHO, 5,8 the main symptoms being high fever (83-98%), dry cough (76-82%), and difficulty in breathing (17-29%). Reference Rodríguez, Sánchez and Hernández4,Reference Liu, Tao and Lei9

To ensure good clinical practice, health professionals must comply with a set of rules and behaviors to reduce the risk of contracting infections through the use of protective barriers in each procedure, consisting in the use of scrubs, gowns, hats, disposable gloves, protective glasses, and masks. Reference Bedoya10,Reference Quiroz-Romero11 According to the manufacturers, surgical masks must achieve efficient filtration, resistance to fluids, pressure differential, and flammability. These masks must create a hermetic seal against the skin, preventing the passage of particles, such as aerosols or splashes that may contain bacteria or viruses. Mask quality certification relies on 2 types of tests to assess filtration efficiency, including quantitative and qualitative tests, such as the particulate filtration efficiency (PFE) test and the bacterial filtration efficiency (BFE) test. Reference Quiroz-Romero11,Reference Umer, Haji and Zafar12 Obtention of this certification has a direct impact on the biosafety of professionals and patients. However, effective prevention of infectious diseases depends on the type of mask used.

Fear of the spread of serious respiratory diseases persists, as in the case of the recent coronavirus pandemic and is largely due to the current lack of effective antiviral drugs and vaccines. Reference Aiello, Perez and Coulborn13,Reference Wang, Barasheed and Rashid14 The WHO and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend a series of fundamental preventive measures, such as protective equipment for health personnel during the care of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, one of the most effective being masks. However, the WHO suggests their use only in the presence of symptoms, and the CDC indicates that the use of N95 respirators is exclusively for health personnel and not for the general public. Reference Benitez15 These masks play an important role in the control of the spread of aerosols in the case of coughing, talking, or sneezing. Reference Liu and Zhang16,Reference Liao, Xiao and Zhao17 Therefore, the purpose of this research was to identify and synthesize all the current information comparing the efficacy of dental masks, to increase our knowledge about the correct use of different types of masks and filters to prevent the spread and contagion of the COVID-19 virus and other infectious diseases.

METHODS

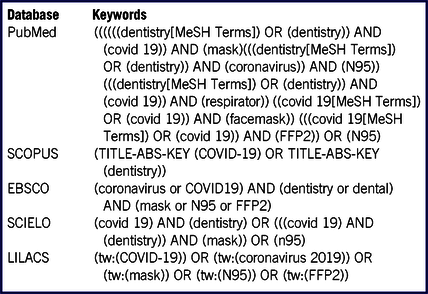

A bibliographic search was carried out in the main databases of the international scientific literature on health sciences (MEDLINE) by means of PubMed, EBSCO, SCOPUS, SCIELO, and the Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences (LILACS), using the following keywords: masks, COVID-19, and dentistry. Articles without language restriction up to May 31, 2020, were obtained. Experimental studies, literature review articles, and systematic reviews were used and opinion articles, letters to the editor, and editorials were excluded (Table 1).

TABLE 1 Search Strategies in the Main Databases

Types of Masks

When a pandemic begins difficulties arise due to the lack of vaccines and ideal treatments for the disease, and, therefore, protection barriers play an important role in controlling the spread and prevention of the disease. Reference Sigua-Rodriguez, Bernal and Lanata18 Taking this into account, 2 types of masks have been described: surgical and conventional (or respiratory). The efficacy of these masks depends on their structure and filtering capacity. In this sense, respiratory masks guarantee better protection compared with surgical masks, both of which are disposable. Reference Hirschmann, Hart and Henckel19

Under the European standard, surgical masks are considered a medical device with an official nomenclature of the EN 14683 standard that classifies these masks as Type I, Type II, and IIR. The latter is classified as the most effective for presenting a microbial barrier and resistance to splashes, offering a filtration rate of around 80%. Reference Sigua-Rodriguez, Bernal and Lanata18,Reference Lepelletier, Grandbastien and Romano-Bertrand20 They are designed for protection in only 1 direction to avoid the transmission of infectious agents carried by the user. They prevent the passage of microorganisms present from the inside out; therefore, the use of these masks is recommended for COVID-19 patients. Reference Hirschmann, Hart and Henckel19,Reference Azap and Erdinç21,Reference Long, Hu and Liu22 However, these surgical masks do not ensure a good hermetic seal, and thereby allow particles to enter around the edges.

The classification of respiratory masks is independently certified by 2 major entities: the European Committee for Standardization (EN) and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Both entities guarantee a percentage of filtering capacity of particles that measure 0.3 microns in diameter. Respiratory masks must have multiple layers of polypropylene and electrostatic charge, providing adequate protection in 2 directions; that is, they are able to filter both incoming and outgoing air and must be resistant to liquid spray, blood splatter, and of other bodily fluids. Likewise, masks are considered to be effectively adjusted when a hermetic seal is achieved on contact with the skin. Reference Liao, Xiao and Zhao17,Reference Hirschmann, Hart and Henckel19,Reference Azap and Erdinç21,23,Reference Boškoski, Gallo and Wallace24

The European standard EN 149: 2001 establishes 3 categories or levels of protection for respiratory masks according to their filtering facepiece (FFP) parts, and these are divided into FFP1, FFP2, and FFP3, with a particle filtration capacity of 0.3 microns of 80%, 95%, and 99%, respectively. Reference Hirschmann, Hart and Henckel19,Reference Lepelletier, Grandbastien and Romano-Bertrand20 On the other hand, the NIOSH establishes 9 respirator classifications, all with a particulate filtering capacity combining the respirator series (N, R, or P) and the level of efficacy (95%, 99%, 100%). The first part of the respirator classification indicates the resistance of the filter to degradation when exposed to oil-based aerosols, whereas the N series is for use in particulate environments and oil-free aerosols, and the R and P series are for use in particulate environments with and without oil. The number determines the filtering capacity of 0.3-micron particles, being measured in percentages of 95%, 99%, and 100%. Reference Liao, Xiao and Zhao17,23,Reference Howard25

The use of N95 masks has been considered a US standard administered by the NIOSH. These masks are designed to protect users from air particles, including aerosols, Reference Offeddu, Fu and Fong26 with a particle filtration capacity of 0.3 microns of 95% and have less leakage in the face seal due to the tight fit to the user’s face Reference Hirschmann, Hart and Henckel19,Reference Long, Hu and Liu22,Reference Boškoski, Gallo and Wallace24,Reference Smith, MacDougall and Johnstone27,Reference Ma, Shan and Zhang28 N99 masks have a 0.3-micron particle filtration capacity of 99%, while N100 masks provide 99.7% filtration protection. 23

On the other hand, the use of KN95 respirators of Chinese origin are available in the dental market and comply with GB 2626-2006 regulations. These masks have a filtration capacity of 94-95% of particles with 4 overlapping layers, which are fused together to avoid the exit of particles from the carrier and the aspiration of aerosols or drops that may contain the virus. These respirators are considered to be functionally similar to the NIOSH-certified N series. Reference Umer, Haji and Zafar12,23

Mean Life of the Masks

An important approach to moderating mask wear and avoiding scarcity is to adopt strategies for mask reuse. Reference Liao, Xiao and Zhao17,Reference Sigua-Rodriguez, Bernal and Lanata18 The CDC recommends 2 conservation strategies for respirators: extended use and limited reuse. Reference Prakash, Rao and Nair29,Reference Kobayashi, Marins and dos Santos Costa30

Surgical and respiratory masks are for single use per patient. However, conservation of these resources is imperative in this crisis. Thus, an alternative is use with multiple patients, Reference Umer, Haji and Zafar12,Reference Lepelletier, Grandbastien and Romano-Bertrand20 but with strict biosecurity conditions, involving safeguards, evaluation of sealing, and mask integrity during use. A second surgical mask can be used on the respiratory mask to serve as direct protection against patient fluids, being discarded after use.

In the case of using only 1 respiratory mask while under great exposure to infectious droplets due to the aerosols, it is not recommended to reuse the same mask between patients because of a higher risk of contamination. However, this condition can be ameliorated with the use of a face protection mask or the use of 2 masks, which will allow the second protective mask to be discarded and the facial mask disinfected, thereby preserving the respiratory mask. Reference Umer, Haji and Zafar12,Reference Lepelletier, Grandbastien and Romano-Bertrand20

The second form of conservation of respiratory masks is limited reuse, which is the removal of the mask after each patient with restrictions limiting the number of uses. However, this requires strict validation regarding cleaning, sterilization, and functional performance. Reference Prakash, Rao and Nair29 It is important to consider that the duration of use for surgical masks should not exceed 4 h and 8 h for FFP masks. Reference Hirschmann, Hart and Henckel19,Reference Lepelletier, Grandbastien and Romano-Bertrand20,Reference Bein, Bachmann and Huggett31

In the literature, few studies have evaluated the reuse of masks. One study evaluated health policies of 27 countries (in Europe and the Americas), finding that widespread use and limited reuse of masks is allowed in 10 countries. On the other hand, more than 60% of the countries do not recommend 1 of these 2 strategies. Reference Kobayashi, Marins and dos Santos Costa30

How to Use

In 1 of its publications, the CDC recommends how to use and dispose of respiratory masks. Reference Ather, Patel and Ruparel32

Placement

Secure the ties or elastic bands to the middle of the back of the head and neck, and then adjust the band to the bridge of the nose, around the face and chin. Finally, check the fit of the mask. After placement, hands must be disinfected with alcohol and washed with soap for at least 20 s.

Removal

The front of the mask is contaminated and should not be touched. Hold the ties or elastic bands of the mask and remove them upward without touching the front. Discard in the indicated garbage container and wash your hands with soap for at least 20 s.

Sterilization

Given the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), sterilization and disinfection methods have been determined to prolong the effectiveness of the masks for the prevention of virus transmission. It is important that the sterilization treatment does not deteriorate the material of the respiratory mask, which would decrease the filtering power against infectious pathogens. The CDC has recommended different chemical, radioactive, and physical sterilization methods. Reference Boškoski, Gallo and Wallace24

Different decontamination strategies, such as sterilization by exposure to ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI), ethylene oxide, or vaporized hydrogen peroxide, have been shown to be effective in maintaining adequate protective function. Reference Kobayashi, Marins and dos Santos Costa30,Reference Perkins, Villescas and Wu33-Reference Friese, Veenema and Johnson36

In 1 study, different common sterilization methods for masks were performed including heat treatment, cabinet UVGI sterilizer, steam, alcohol solutions, and chlorine-based solutions. The last 2 methods caused degradation of the static charge required by the FFR. On the other hand, dry heat in the presence of humidity at 100°C preserved the characteristics of the N95 respirator, limiting temperature and humidity for 30 min. This study determined that the best sterilization method was UVGI (254 nm, 8W) with 3.6 J/cm2. Reference Liao, Xiao and Zhao17

UVGI uses UV-C radiation to inactivate microorganisms causing damage to deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), preventing replication. Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of UVGI in reducing contamination by drops applied to the N95 respirator, with effective destruction of SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Reference Boškoski, Gallo and Wallace24,Reference Hamzavi, Lyons and Kohli37,Reference Nogee and Tomassoni38 However, the use of UVGI for the destruction of this new virus requires further studies to establish the exact exposure or light intensity required, as 3M reports have shown that UVGI treatments damage the mask, while other studies show that this technique had no impact on the masks. Reference Liao, Xiao and Zhao17

Combination strategies have been studied, including the use a solution of sodium hypochlorite with microwave-generated steam UVGI, demonstrating effective sterilization with a reduction of multiple registrations of MS2 bacteriophage virus from masks. This virus is 7-10 times more resistant to aerosolization and ultraviolet light than the coronavirus. Reference Turgeon, Toulouse and Moineau39

The susceptibility of the virus to gamma irradiation has shown good disinfecting ability by penetration of all the layers of the respirators. However, the use of ionizing radiation is limited because gamma radiation cannot be performed in a health-care center, requiring the need for transportation to another location entailing a risk for the personnel transporting the masks. Reference Prakash, Rao and Nair29

On the other hand, the CDC reports that some autoclave methods at 160°C in dry heat, 70-75% isopropyl alcohol and soapy water can deteriorate the filter of the respirators, and consequently allow the access of particles through the mask. Reference Boškoski, Gallo and Wallace24

For mask sterilization, certain requirements must be taken into account, such as the efficacy against the SARS-CoV2 organism, avoiding damage to the respirator filtration changes in the physical characteristics of the respirators, and ensuring biosafety to the persons who must wear the respirator mask. Reference Prakash, Rao and Nair29

Proposed Alternatives of Masks for Dentists

According to the information obtained from COVID-19, the transmission routes are direct or indirect contact with contaminated patients, saliva drops, Reference Umer, Haji and Zafar12 and large aerosol particles suspended in the air (up to 1 m away), which remain present for a short period of time. Reference Liao, Xiao and Zhao17,Reference Azap and Erdinç21,Reference Ferioli, Cisternino and Leo40 In dentistry, there is direct contact with the patient through fluids, such as blood or saliva, and many dental treatments generate aerosols. It should also be taken into account that the SARS-CoV2 virus has affinity for the angiotensin 2 converting enzyme receptor (ACE-2), which is found in the respiratory tract and the salivary gland ducts, producing a high viral load in saliva. Reference Umer, Haji and Zafar12,Reference Liao, Xiao and Zhao17

Different models of masks are available, making it difficult to choose the most suitable type of respirator for dental care. Therefore, according to past recommendations, it is recommended to perform fit tests of masks for health personnel to determine the best fit and hermetic seal according to facial dimensions, ethnic origin, and appearance of the fit.

The literature recommends that surgical masks should not be used as a substitute for respiratory masks. Reference Hirschmann, Hart and Henckel19,Reference Smith, MacDougall and Johnstone27,Reference Coulthard41 The use of an N95, FFP2, and FFP3 mask is recommended for personnel working with aerosols. Filtration is achieved by combining a polypropylene network and electrostatic charge, Reference Azap and Erdinç21 thereby explaining their good protective effect against aerosols, and the reason why respirators should not be used by the general public. Reference Long, Hu and Liu22,Reference Bein, Bachmann and Huggett31,Reference Zhou, Yue and Mu42

On analyzing the filtering capacity according to the mask classification, the N95 has shown a similar filtration efficacy to that of FFP2 or KN95. Reference Boškoski, Gallo and Wallace24 Regarding mask sterilization, although it is necessary to determine the exact UVGI doses for mask sterilization against the SARS-CoV-2 virus, this strategy provides a possibility to extend the use of the limited supply of respirator masks against COVID-19, being both profitable and accessible. Reference Perkins, Villescas and Wu33

A major problem with respirator masks is discomfort and the generation of humidity inside, decreasing air permeability. Therefore, a super absorbent polymer (SAP) has been designed for use in respirator masks. This harmless material absorbs large amounts of liquid is used in baby diapers, sanitary napkins, and incontinence pads. An absorbent layer or SAP pad is cut according to the shape and size of the respirator and finally placed inside the respirator. The SAP pad helps to quickly absorb exhaled moisture, leading to a longer mask life cycle and providing greater comfort to the professional. Reference Song, Xie and Zhu43

DISCUSSION

In these times of international health alert, dentists have a high risk of contracting COVID-19 due to direct contact with body fluids during patient care. Therefore, the use of PPE is extremely important for the protection of dentists, with masks being part of the clothing for daily use to avoid aspiration of virus particles. Reference Quispe-Salcedo44 The aim of this literature review was to identify and synthesize all the current information available on the efficacy of the masks in dentistry to prevent the spread of the new COVID-19.

Currently the different types of masks in the market cause confusion at the time to choosing the most adequate equipment. There are 2 types of masks: surgical masks and respiratory masks. Surgical masks have a filtering capacity of 80% of particles compared with N95 and FFP2 respirators, which have a 95% filtering capacity of particles measuring 0.3 microns in diameter due to their multiple layers of polypropylene in combination with an electrostatic charge. This good filtering capacity has led to recommending their use a global standardization. Reference Umer, Haji and Zafar12,Reference Liao, Xiao and Zhao17,Reference Hirschmann, Hart and Henckel19,Reference Boškoski, Gallo and Wallace24,Reference Smith, MacDougall and Johnstone27

Ideally, 1 mask is used per patient. However, regulatory authorities are trying to take action involving the widespread use and limited reuse of masks due to the global shortage of PPE. One of the most recommended strategies is the prolonged use of the respirator for different patients, using a second surgical mask over the respirator to protect it from fluids to preserve its integrity. However, it is highlighted that this strategy is only a resource for the protection of health personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic, due to the shortage of this equipment. Reference Lepelletier, Grandbastien and Romano-Bertrand20,Reference Kobayashi, Marins and dos Santos Costa30

Regarding the mask sterilization method, many studies report that COVID-19 is susceptible to sterilization by UVGI, which inactivates these microorganisms by damaging their DNA. Reference Liao, Xiao and Zhao17,Reference Prakash, Rao and Nair29 Likewise, this method has shown great efficacy, maintaining the protective function of the mask and filtering power against pathogens. In the same way, hydrogen peroxide vapor sterilization is an effective method to prolong mask efficacy. However, these methods still require further study to ensure preservation of the physical characteristics of the respirators and adequate biosecurity for dentists. Reference Kobayashi, Marins and dos Santos Costa30,Reference Perkins, Villescas and Wu33-Reference Turgeon, Toulouse and Moineau39

There are different studies of the efficacy and recommendations for the use of masks to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Reference Hirschmann, Hart and Henckel19,Reference Azap and Erdinç21,Reference Kobayashi, Marins and dos Santos Costa30 The information described in this study highlights the importance of the resistance of the masks to droplets and aerosols for the prevention of inhalation of contaminating particles, guaranteeing biosecurity to dentists. Recommendations are based on the largest evidence available. On the other hand, there are several limitations regarding sterilization for reuse of respirators that should be recognized. Further studies are required to standardize adequate and effective exposure to prolong the efficacy of respirator masks. Likewise, it is recommended that dental centers adhere to the correct use of respirators, otherwise, they risk endangering their health and the transmission of COVID-19 to those in their work environment.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of N95 or FFP2 respirators is recommended as part of PPE for dental use during patient care. For a longer useful life of respiratory masks, it is recommended to add a surgical mask together with the use of a face mask. Likewise, at the time of placing the mask, it is important to ensure a correct fit and hermetic seal against the skin. Likewise, at the time of removal, avoid direct contact with the external part of the mask. Finally, as a method of mask sterilization, up to now the use of UVGI, hydrogen peroxide steam, and heat guarantee the preservation of the filtering and structural capacity of masks, providing dentists with adequate protection. Nonetheless, more studies are needed for more information on the exact doses of UVGI to implement.