Juvenile offenders constitute 5% of detained populations in Western countries (Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Doll and Långström2008). On any given day, around 70,000 children under the age of 18 are engaged in the US criminal justice system, among which 53,000 are detained in various correctional facilities (Alcorn, Reference Alcorn2014; Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Doll and Långström2008). Everyday life of detained youths, similar to adult ex-prisoners, is characterized by abuse, neglect, insufficient access to stable housing/food/education opportunities, insecure family environment, chaotic community conditions, and poor access to healthcare facilities (Anoshiravani, Reference Anoshiravani2020; Borschmann et al., Reference Borschmann, Janca, Carter, Willoughby, Hughes, Snow, Stockings, Hill, Hocking, Love, Patton, Sawyer, Fazel, Puljević, Robinson and Kinner2020; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Mok, Lau and Hou2023). These social determinants contribute to a disparity of mental health between juvenile offenders and their non-justice-involved peers, with the prior at increased risk of psychiatric disorders, self-harm, substance abuse, and delinquent behaviors (Anoshiravani, Reference Anoshiravani2020). There is a need to identify and compare multiple levels of psychological adjustment and their associated factors among juvenile offenders.

Mental health of juvenile offenders

Involvement in the US juvenile justice system can be criminogenic, and most youths with system involvement are very likely to have previous experiences of trauma or other risk factors for both mental health problems and justice system involvement (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Perez, Cass, Baglivio and Epps2015; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Li, Liang and Hou2021). Some criminogenic factors, such as disadvantaged social economic status and substance abuse, could put adolescents at increased risk of committing crime and developing mental health problems (Agnew, Reference Agnew2015; B. K. E. Kim et al., Reference Kim, Gilman, Kosterman and Hill2019; Reiss et al., Reference Reiss, Meyrose, Otto, Lampert, Klasen and Ravens-Sieberer2019; Weber & Lynch, Reference Weber and Lynch2021). The positive association between crime and mental health problems was evidenced in a national sample of youth in the US (Coker et al., Reference Coker, Smith, Westphal, Zonana and McKee2014). Committing serious crime is also a major life event that not only carries numerous costs to society but also puts the offenders in the face of stressful consequences such as jail/detention, economic burdens of legal processes, broken family relationships, and stigma (Day & Koegl, Reference Day and Koegl2019; Lambie & Randell, Reference Lambie and Randell2013). Mental health problems are more common among detained juveniles relative to their non-detained counterparts (Borschmann et al., Reference Borschmann, Janca, Carter, Willoughby, Hughes, Snow, Stockings, Hill, Hocking, Love, Patton, Sawyer, Fazel, Puljević, Robinson and Kinner2020; Heller et al., Reference Heller, Morosan, Badoud, Laubscher, Jimenez Olariaga, Debbané, Wolff and Baggio2022). A recent global scoping review found that the lifetime prevalence of mental disorders ranged between 0% and 95%; 66.8% of male and 81% of female adolescents in detention were diagnosed with at least one mental disorder in the US (Borschmann et al., Reference Borschmann, Janca, Carter, Willoughby, Hughes, Snow, Stockings, Hill, Hocking, Love, Patton, Sawyer, Fazel, Puljević, Robinson and Kinner2020). The global review showed that the prevalence of any anxiety and depressive disorders measured at a particular timepoint in their life ranged from 3.4%–36% for males and 14%–63% for females; the large ranges suggest some heterogeneity in mental health (Borschmann et al., Reference Borschmann, Janca, Carter, Willoughby, Hughes, Snow, Stockings, Hill, Hocking, Love, Patton, Sawyer, Fazel, Puljević, Robinson and Kinner2020). More importantly, juvenile offenders’ mental health problems usually persist after detention, with persistent psychiatric disorders for as long as 15 years (Abram et al., Reference Abram, Zwecker, Welty, Hershfield, Dulcan and Teplin2015). This could complicate juvenile offenders’ transition from adolescence to adulthood.

Longitudinal patterns of mental health among juvenile offenders

Only a handful of studies have investigated long-term psychological consequences following committing crime. In a longitudinal cohort study of 1,216 sentenced adult prisoners assessed before prison release, and at 1, 3, and 6 months after release, five trajectories were identified with the majority of the participants (51%) falling within the resilience trajectory (i.e., psychological distress consistently below clinical levels) (E. G. Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Spittal, Heffernan, Taxman, Alati and Kinner2016). However, only preexisting psychiatric conditions were found to predict persistent clinical levels of distress (E. G. Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Spittal, Heffernan, Taxman, Alati and Kinner2016).

There is currently a deficit of knowledge about the heterogeneous longitudinal trajectories of psychological adaptation among juvenile offenders, especially those following serious offending (e.g., felony crime). Severity of crime was shown to be highly correlated with having one or more comorbid psychiatric disorders among juvenile offenders in detention center (Taşkıran et al., Reference Taşkıran, Mutluer, Tufan and Semerci2017). Prospective evidence has shown that serious violent offending was associated with subsequently increased anxiety and depressive symptoms among 503 boys who were followed up from the age of seven years to 11–16 years (Jolliffe et al., Reference Jolliffe, Farrington, Brunton-Smith, Loeber, Ahonen and Palacios2019). Another study of the longitudinal pattern of antisocial behaviors and internalized symptoms found that adolescents who had chronic and violent patterns of antisocial behaviors also demonstrated more internalized problems (anxiety/depression syndromes) (Sheidow et al., Reference Sheidow, Strachan, Minden, Henry, Tolan and Gorman-Smith2008). One previous study has investigated changes in anxiety, depression, and criminal offending, and their risk factors among 1,216 juvenile male offenders in the five years following their first arrest and found that internalized symptoms and offending decreased after the first arrest, followed by a significant increase over the next few years (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Padgaonkar, Galván, Frick, Steinberg and Cauffman2022). An important point to note is that all participants were considered homogeneous without identifying individual differences and a limited range of risk factors were assessed, namely demographics, processing type (e.g., sanctions, formal processing), and self-report neighborhood quality (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Padgaonkar, Galván, Frick, Steinberg and Cauffman2022). No study to date has comprehensively tested predictors of mental health on different levels of the social ecology of juvenile offenders using robust statistical methods.

Frameworks and models

A comprehensive understanding is needed for psychological adaptation of juvenile offenders. Stress process theory suggested that deprived social contexts can expose individuals to social stressors differently, which led to detrimental health consequences (Pearlin, Reference Pearlin1989). Incarceration is a social stressor that disproportionally occurs among different social groups, with people from ethnic minorities and low social economic status more likely to experience incarceration than their counterparts (Brinkley-Rubinstein & Cloud, Reference Brinkley-Rubinstein and Cloud2020). Stress proliferation theory further elucidated how stressors triggered by one event beget stressors in other life domains (Pearlin et al., Reference Pearlin, Aneshensel and LeBlanc1997; Turney, Reference Turney2014). Involvement with the criminal justice system could proliferate juvenile offenders’ stressors across other life domains, such as dropping out from school, health issues, poorer social relationships, and lower well-being in adulthood (Baćak & Karim, Reference Baćak and Karim2019; Lambie & Randell, Reference Lambie and Randell2013), which, together, ultimately threaten their mental health.

Several frameworks have emphasized the interrelations among different levels of factors in predicting adaptation outcomes. Socioecological perspective highlighted the significance of macro-level contextual factors for understanding psychological adaptation in the face of adversity (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Romero and Klein2015; Panter-Brick & Eggerman, Reference Panter-Brick, Eggerman and Michael2012). Panter-Brick (Reference Panter-Brick2014) further emphasized the multidimensionality of psychological adaptation and proposed that psychological resilience is shaped by the interplay of individuals, family, community, and society at various socio-ecological levels. Relationship-related factors included family belief system and family problem-solving and flexibility (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Romero and Klein2015; Walsh, Reference Walsh2015). Contextual factors on the community level included neighborhood characteristics, sense of community, and social capital. In a similar vein, developmental assets framework suggested that both internal (e.g., positive values, competencies, and positive identity) and external assets (e.g., contextual and relational features of socializing system) could prevent adolescents from high-risk behaviors and strengthen their psychological resilience (Benson et al., Reference Benson, Scales and Syvertsen2011). Mental health of juvenile offenders can be best understood through developmental ecological perspective , an overarching model integrating the theories mentioned above (Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, Reference Bronfenbrenner and Ceci1994). This theory emphasized that achievement of developmental milestones can be attributed to the risks and resources within children’s ecological system ranging from individual (e.g., victim of violence), relationship (e.g., with parents and intimate partners), and environment (e.g., high crime neighborhood).

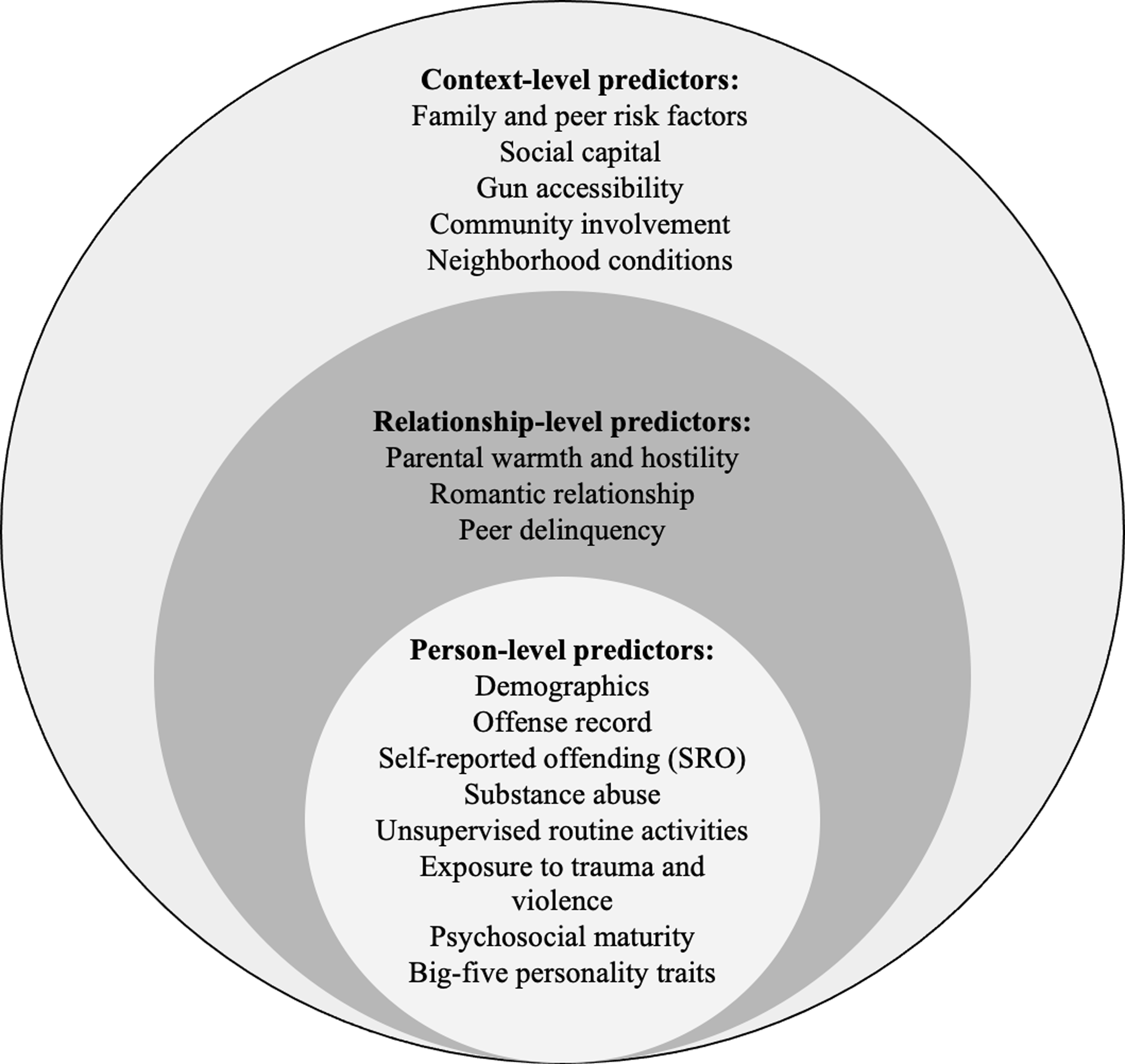

In the present study, we proposed risk and resilience factors across different social-ecological levels (individual, relationship, contextual) for predicting symptom trajectories. Informed by the developmental ecological perspective, predictors were organized across three levels. Individual level predictors included demographic factors (e.g., age, gender, race), history of substance abuse, violence exposure, personality, and psychosocial maturity, which were well-established predictors for mental health (Barnert et al., Reference Barnert, Perry and Morris2016; Visser et al., Reference Visser, Bolt, Finkenauer, Jonker, Weinberg and Stevens2021). In addition, we also tested offending behaviors (e.g., self-report delinquency and official offense record) that were believed to co-occur with mental illness among adolescents (Reising et al., Reference Reising, Ttofi, Farrington and Piquero2019). Relationship level predictors were located in juveniles’ proximal social contexts with parents, peers, and romantic partners. Context level predictors tested deprived structural factors such as dysfunctional family context (e.g., parental divorce, crime and substance abuse of family members), peer context (e.g., friends arrested and jailed), and neighborhood context (e.g., chaotic neighborhood) that put juveniles at an increased risk of mental disorders and crime (Visser et al., Reference Visser, Bolt, Finkenauer, Jonker, Weinberg and Stevens2021).

The present study

This study aims to (a) identify heterogeneous trajectories of probable psychopathology (anxiety and depressive symptoms) and (b) examine a list of predictors on person-, relationship-, and context-levels among juvenile offenders in the seven years after committing serious offenses. Four prototypical psychological outcome trajectories have been consistently observed following trauma (Galatzer-Levy et al., Reference Galatzer-Levy, Huang and Bonanno2018). Resilience denotes psychiatric symptoms lower than clinically significant levels over time; recovery denotes initial presentation of clinically significant symptoms followed by recovery to nonclinical levels; delayed onset denotes initial nonclinical symptoms that elevate above clinical levels; and chronicity denotes clinically significant symptoms over time (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Romero and Klein2015; Galatzer-Levy et al., Reference Galatzer-Levy, Huang and Bonanno2018). Conceptual model of multi-level predictors in our prediction model is illustrated in Figure 1. Predictors were selected based on previous evidence in trauma studies (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Romero and Klein2015) and trajectories studies of mental health among juvenile offenders (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Padgaonkar, Galván, Frick, Steinberg and Cauffman2022). Based on the socioecological perspective of resilience (Panter-Brick, Reference Panter-Brick2014), this study examined predictors of outcome trajectories on personal, relationship, and contextual levels in juvenile offenders’ life. We expect that the four trajectories of probable psychopathology, namely resilience/stable low trajectory, recovery, delayed onset, and stable high trajectory, will emerge in the current sample of juvenile offenders. We also expect that the trajectories of outcomes will be predicted by a combination of person-level, relationship-level, and context-level factors.

Figure 1. Conceptual model of multi-level predictors in LASSO logistic regression model.

Method

Participants and procedure

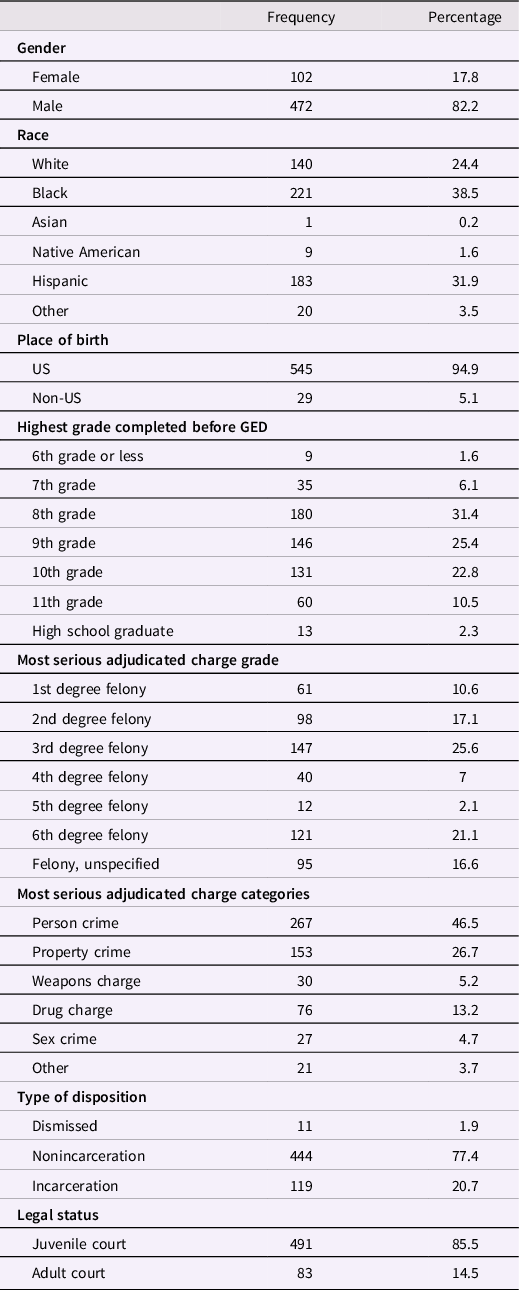

Secondary dataset from the Pathways to Desistance study (Mulvey, Reference Mulvey2017) was used. The present study focused on juvenile offenders with serious offenses but without prior incarceration. The inclusion criteria in the current study were (a) no histories of being locked up in any detention center or jail; (b) serious offense that was convicted as felonies; and (c) completed data at least three timepoints across the 11 consecutive interviews. A total of 574 eligible participants were included in the final analysis. The 574 participants aged between 13.82 and 18.29 years (M = 16.10, SD = 1.08); 82.2% were male. Most of them (38.5%) were Black, 31.9% Hispanic, and 24.4% white. Demographics of the participants are summarized in Table 1. The baseline interview was conducted between 2000 and 2003. The first six follow-up interviews were scheduled in a 6-month interval at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months while the remaining four follow-up interviews were scheduled every year at 48, 60, 72, and 84 months. Computer-assisted interview (CAI) technology was used for data collection. Research staff read the instructions to participants who then reported answers by means of CAI technology. Interviews were conducted at the participants’ homes, public places, or criminal justice facilities if participants were under supervision. Other details regarding sampling procedures, data collection methodology, and previous publications can be accessed on the study website: https://www.pathwaysstudy.pitt.edu/. The present study obtained the research ethics committee’s approval from The Education University of Hong Kong.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of all participants at baseline interview (N = 574)

Measures

Two outcome variables and a total of 91 person-level, relationship-level, and context-level predictors were examined. Outcome variables were assessed at both baseline and 10 follow-ups. All predictors were measured at the baseline, except Big Five personality traits, which were measured at the 4th follow-up at the 24th month. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each scale to measure internal reliability. The commonly accepted criterion for Cronbach’s alpha is: α ≥0.9 (excellent), 0.9 > α ≥0.7 (good), 0.7 > α ≥ 0.6 (acceptable), 0.6 > α ≥ 0.5 (poor), and α < 0.5 (unacceptable) (Kline, Reference Kline2013).

Anxiety and depressive symptoms

Subscales in Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis, Reference Derogatis1983) were used to assess anxiety and depressive symptoms in the past week on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all, 4 = extremely). Anxiety subscale consisted of six items with the average scores ranging from 0 to 4. A cutoff score of .35 or higher was used to indicate clinically significant anxiety symptoms. Depression subscale consisted of six items with average scores ranging from 0 to 4. A cutoff score of .28 or higher was used to indicate clinically significant depressive symptoms (Derogatis, Reference Derogatis1983). The scores on anxiety and depressive symptoms at baseline and 10 follow-ups were used. Alphas were good across the 11 timepoints (range = .74–.86).

Person-level predictors

Demographics

Participants reported their gender, age at the initial interview, race (i.e., White, Black, Asian, Native American, Hispanic, and others), place of birth (USA vs. non-USA), education-related variables (e.g., grades completed, number of times suspended), employment-related variables (e.g., money earned per hour), and number of children they had.

Offense record

Four items assessed participants’ official record of criminal offense at the initial interview. Participants reported their adjudicated charge in terms of serious offense (1 = 6th degree felony, 6 = 1st degree of felony), type of offense (person crime, property crime, weapons crime, drug crime, sex crime, and other crime), type of sentencing (1 = dismissed, 2 = nonincarcerated – including fines or restitution, probation, nonincarcerated residential placement, and 3 = incarcerated/jail), and court for initial referring petition processing (juvenile or adult court). Participants also reported lifetime number of arrests and age at the first arrest.

Self-reported offending (SRO)

The 22-item Self-Reported Offending (SRO) scale was used to capture juveniles’ involvement in illegal activities (Huizinga et al., Reference Huizinga, Esbensen and Weiher1991) in the past year. Sum frequencies reported across five types of crime committed were calculated: 22 criminal acts, 19 non-drug offenses, 11 aggressive offenses, 10 income offenses, and three non-drug income offenses. We did not calculate Cronbach’s alpha for SRO because the count number of criminal acts was used.

Substance abuse

Modified Substance Use/Abuse Inventory (Chassin et al., Reference Chassin, Rogosch and Barrera1991) was used to assess frequencies of substance abuse (i.e., marijuana, sedatives, stimulants, cocaine, opiates, ecstasy, hallucinogens, inhalants, amyl nitrate, other drugs, alcohol, and cigaret) in the past six months. Chassin et al. (Reference Chassin, Rogosch and Barrera1991) asked the frequency of substance use in both past three months and past year, and used response options ranging from “abstinence” to “more than daily use”. Whereas the present study asked substance use in the past six months and used the revised response options ranging from “not at all” to “every day”. Higher scores reflected more frequent substance use. Lifetime dependency symptoms were measured by 10 items and participants responded with “yes” or “no” for each of the dependency symptoms (e.g., having the urge to use the substance and cannot stop oneself). Similar to the previous research, (Chassin et al., Reference Chassin, Rogosch and Barrera1991), dependency symptoms in the present study were indicated by the total count of lifetime symptoms attributable to alcohol use and the total count of lifetime symptoms attributable to drug use (range = 0–10). We did not calculate Cronbach’s alpha for this scale because the count of dependance symptoms was used.

Unsupervised routine activities

Four items from Monitoring the Future Questionnaire (Osgood et al., Reference Osgood, Wilson, O’Malley, Bachman and Johnston1996) were used to measure the frequency of unsupervised activities in the absence of authority figures (e.g., How often did you ride in car for fun?) on a 5-point scale (1 = never, 5 = Almost every day). Higher mean scores indicated more frequent involvement in unsupervised activities. Internal consistency was acceptable (α = .62).

Exposure to trauma and violence

The Exposure to Violence Inventory was used to measure the frequency of exposure to 13 traumatic events (Selner-O’Hagan et al., Reference Selner-O’Hagan, Kindlon, Buka, Raudenbush and Earls1998). Six items assessed violence that participants experienced and seven items assessed violence that they observed. Three summed scores were calculated to reflect participants' exposure to violence as a victim (range = 0–6), as a witness (range = 0–7), and total scores on both victim and witness (range = 0–13). We did not calculate Cronbach’s alpha for ETC because the count of traumatic events was used.

Psychosocial maturity

The 30-item Psychosocial Maturity Inventory was used to measure psychosocial development in three dimensions (Greenberger et al., Reference Greenberger, Josselson, Knerr and Knerr1975): self-reliance (e.g., sense of control initiative), identity (e.g., clarity of self-concept), and work orientation (e.g., standards of competence). Participants rated the items on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater psychosocial maturity. The alpha was good (.89) in the current administration.

Big Five personality traits (4th/24-month follow-up)

The 120-item NEO-Five Factor Inventory Short Form (NEO-PI-SF) was adopted to measure five subscales of personality, namely neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness at the 4th follow-up (24 months) (Costa & McCrae, Reference Costa and McCrae1992). Participants rated each statement on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s alphas for the five subscales were acceptable (α = .65–.77).

Relationship-level predictors

Parental warmth and hostility

The 42-item Quality of Parental Relationships Inventory (Conger et al., Reference Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz and Simons1994) was used to assess participants’ relationship quality with mothers and fathers, each with 21 items on a 4-point scale (1 = always, 4 = never). Summed scores were calculated for mother warmth, mother hostility, father warmth, and father hostility. Alphas for the four subscales were good to excellent (.92, .85, .94, and .87, respectively).

Romantic relationship

Items from the Quality of Romantic Relationship Inventory (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Sarason, Sarason, Solky-Butzel and Nagle1997) assessed participants’ romantic relationships on a 4-point scale (1 = Would not care at all, 4 = Would get very upset with me) (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Sarason, Sarason, Solky-Butzel and Nagle1997). Tolerance of deviance (two items) assessed whether partner knew their delinquent behaviors; monitoring (five items) assessed how much romantic partner monitored the behavior of the participant; and antisocial influence (seven items) assessed whether or not their partners encouraged them to engage in antisocial behaviors. Alphas for tolerance of deviance and monitoring were acceptable (.67) and good (.81), respectively. Alpha was not calculated for antisocial influence subscale because it counted the exact number of seven antisocial behaviors that partners encouraged them to engage in.

Peer delinquency

Twelve items were adopted to assess friends’ antisocial behavior, denoting the frequency of friends’ engagement in antisocial behaviors, and antisocial influence (seven items), denoting frequency of friends’ influence on engagement in antisocial behaviors. Participants rated each item on a 5-point scale (1 = None of them; 5 = All of them), with higher mean scores indicating greater peer delinquency. Alphas for the two subscales were excellent (.91) and good (.88).

Context-level predictors

Family and peer risk factors

Family risk factors included family members’ history of being arrested, jailed or prisoned, or in mental hospital (no/yes), and biological parents’ marital status, education level, substance abuse, and history of being arrested or in jail/prison. Peer risk factors were assessed in terms of number of friends, the count of four closest friends arrested, the count of four closest friends jailed, and the count of closest friends in mental hospital. We did not generate Cronbach’s alpha for family and peer risk factors because the count number of peers and family members was used.

Social capital

The Social Capital Inventory assessed participants’ connectedness to the community on two dimensions (Nagin & Paternoster, Reference Nagin and Paternoster1994). Closure and integration consisted of five items assessing social integration and three assessing intergenerational closeness on a 4-point scale (1 = Never, 4 = Often); high scores indicated more social integration. Perceived opportunities for work consisted of five items assessing participants’ attitudes towards the labor market in the community on a 5-point scale (1 = Strongly Agree, 5 = Strongly disagree). Scores were reverse coded with higher scores indicating higher perceived opportunities for work. Alphas for the two subscales were acceptable (.69) and good (.77).

Gun accessibility

Participants were asked how easy they could purchase guns in their neighborhood on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree) and to estimate prices of the two types of guns most carried and used by adolescents, namely handguns (.38 mm) and automatic weapons (9 mm). We did not calculate Cronbach’s alpha for gun accessibility because the price was used.

Community involvement

The Community Involvement scale assessed participants’ involvement in four structured community activities, namely sports teams, scouts, church-related groups, and volunteer work. Participants reported whether (no/yes) they have participated in the four activities in their lifetime and in the past six months. Two scores were calculated: lifetime involvement (count of activities independent of recency) and recent involvement (count of activities in the past six months). We did not calculate Cronbach’s alpha for community involvement because the count of activities was used.

Neighborhood conditions

The 21-item Neighborhood Conditions Measure assessed physical environment (12 items; e.g., “Empty beer bottles on the streets or sidewalks”) and social environment (9 items; e.g., “Adults fighting or arguing loudly”). Participants rated each item on a 4-point scale (1 = never; 4 = often). Average scores were calculated for the overall condition, physical environment, and social environment. Alphas for these three subscales were excellent (.94), excellent (.91), and good (.88).

Analytic plan

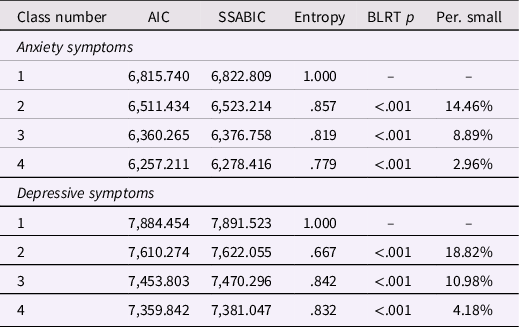

First, to identify latent trajectories of probable anxiety and depression, growth mixture modeling (GMM) was performed using Mplus Version 8.2. Random intercept variances were allowed to be freely estimated, and quadratic parameters were nonsignificant and removed to facilitate model convergence in the final models. Akaike information criterion (AIC), sample-size adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria (SSABIC), Entropy, and Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) were used to evaluate one-class to four-class solutions. Smaller AIC and SSABIC indicated better model fit, and the closer value of entropy to 1 indicated better reliability of class membership. A significant p-value of BLRT indicated that a k-class model demonstrated a significant increase in the model fit than a k-1-class model (Nylund-Gibson & Choi, Reference Nylund-Gibson and Choi2018). Solutions with small classes (<5% of the sample size) could be unstable and hard to replicate and thus were excluded (Nylund-Gibson & Choi, Reference Nylund-Gibson and Choi2018). Final decision was made based on fit statistics, interpretability, and theoretical relevance.

Second, to explore the relative importance of predictors at different levels, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) logistic regression as a form of supervised machine learning was adopted. LASSO applied penalization and performed automatic feature selection by removing less important predictors from the model to address multicollinearity and model overfitting among a large number of predictors (McNeish, Reference McNeish2015). We predicted (a) stable low trajectory against stable high trajectory and (b) recovery trajectory against stable high trajectory. Ten-fold cross-validation with three repetitions was performed to determine the optimal shrinkage parameters (i.e., lambda) for the LASSO models and mean cross-validation estimates of model performance (Kuhn & Johnson, Reference Kuhn and Johnson2013). Model performance was evaluated by Area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC): modest discrimination (.60–.69), acceptable discrimination (.70–.79), excellent discrimination (.80–.89), and outstanding discrimination (.90–1.00). AUC value of 1 indicated perfect discrimination and .5 indicated no discrimination (Hosmer, Reference Hosmer2000; Swets, Reference Swets2014). The resultant variable importance was visualized by descending ordering the nonzero coefficients of predictors on a scale from 0 to 100. R Version 4.1.2 (caret, glmnet packages) was used (R Core Team, 2021).

Results

Growth mixture modeling

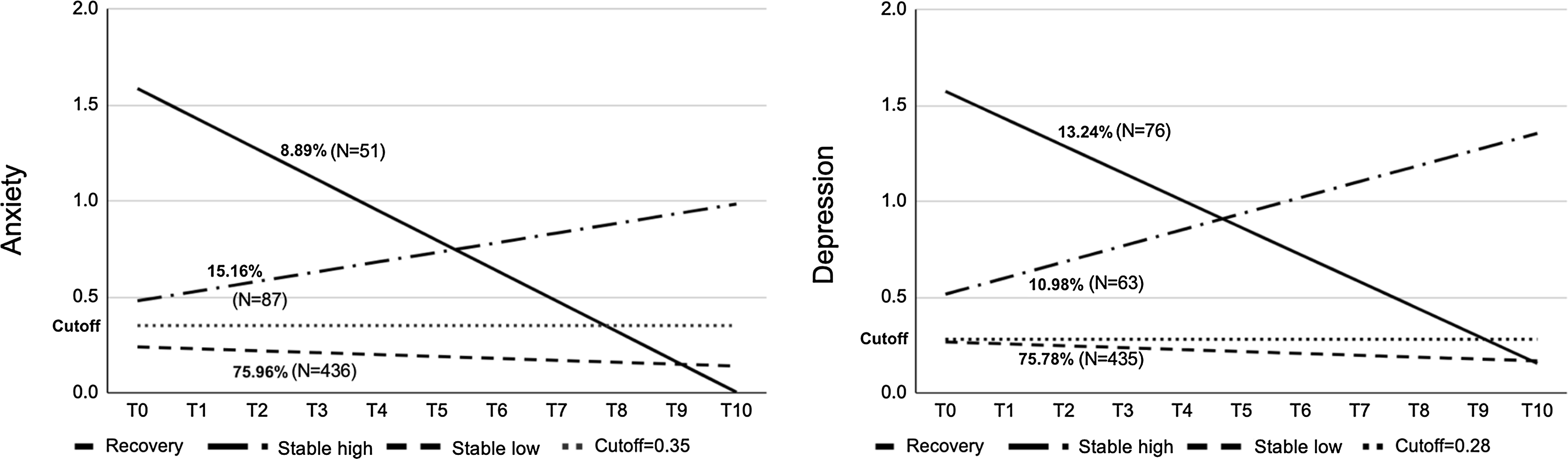

One-class to four-class solutions for both anxiety and depression outcomes were examined with reference to the related model indices (AIC, SSABIC, Entropy, and BLRT) (Table 2). AIC and SSABIC gradually decreased for both outcomes, indicating that model fit improved with increased class number. Significant p-value of BLRTs in the 3-class solution indicated that the 3-class solution performed better than the 2-class solution. The 4-class solution for anxiety and depressive symptoms both included infrequent classes (less than 5%), which were borderline acceptable/unacceptable. Therefore, three-class solutions were selected for both anxiety and depressive symptoms: stable low symptoms, stable high symptoms, and initially high but gradually declining symptoms (recovery) (Figure 2). Entropy of 3-class solutions for both outcomes was high (>.80) suggesting reliability of the class memberships. Even though both anxiety and depressive symptoms were not normally distributed (Supplementary Material 1), the large effect sizes for the three classes (Cohen’s d = 1.57–6.31) could compensate for the inadvertent effect of non-normal data on class solutions (Supplementary Material 2) (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Bi, Sun and Bonanno2022). The class distribution for anxiety symptoms was stable low trajectory (75.96%), stable high trajectory (15.16%), and recovery trajectory (8.89%). The class distribution for depressive symptoms was similar: stable low trajectory (75.78%), stable high trajectory (10.98%), and recovery trajectory (13.24%).

Figure 2. Group means for trajectories of anxiety symptoms and depressive symptoms. Note. Reference lines represent cutoff scores for BSI = .35 for anxiety and .28 for depression.

Table 2. Fit indices for Growth Mixture Models (GMM) for anxiety and depressive symptoms

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion. SSABIC = sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion. BLRT = parametric bootstrapped likelihood ratio test. Per. small = percentage of participants in the smallest group.

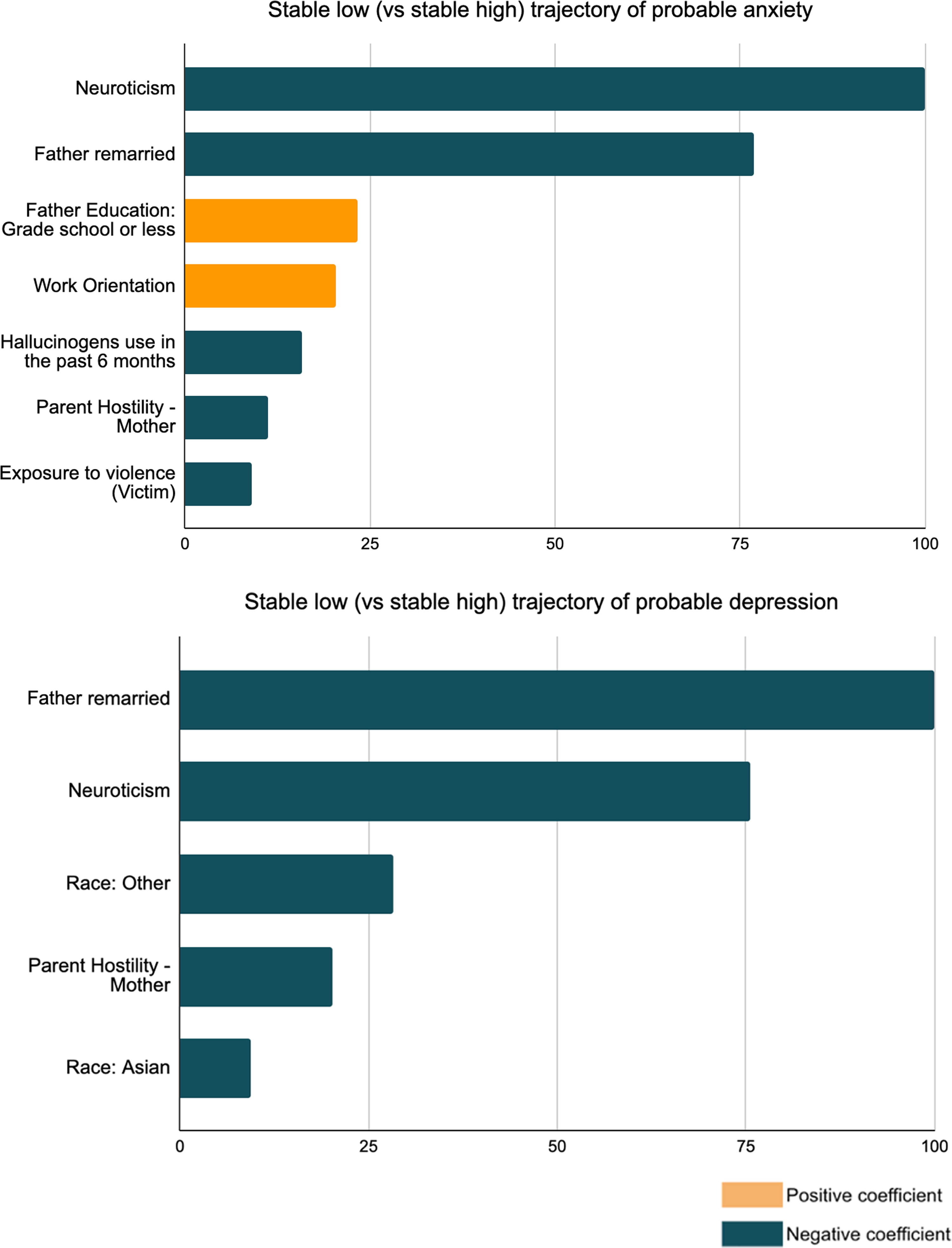

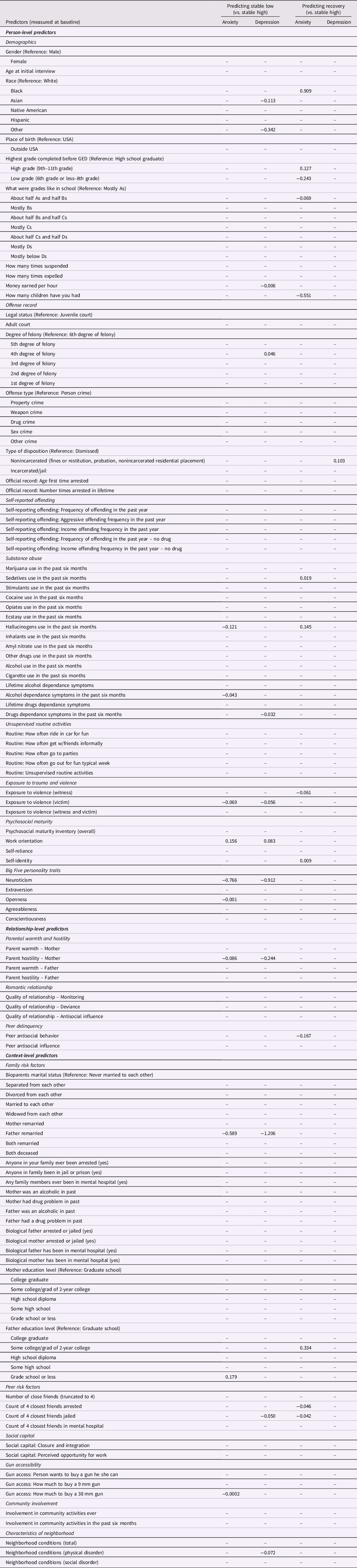

LASSO logistic regression

Four LASSO logistic regression models were performed to identify protective and risk factors of stable low trajectory (vs. stable high trajectories) and recovery trajectory (vs. stable high trajectories) among juvenile offenders. Nonzero coefficients of predictors included person-level, relationship-level, and context-level predictors. Plots of variable importance in descending order are visualized in Figures 3 and 4. Predictors with variable importance less than 10 were omitted. Model performance for the four models was modest to excellent (.60 < AUC < .90). Standardized coefficients of all contributory variables are shown in Table 3.

Figure 3. Relative importance of variables in the LASSO full models predicting stable low (vs. stable high) trajectory of probable anxiety (upper) and probable depression (lower). Variable importance less than 10 were omitted.

Figure 4. Relative importance of variables in the LASSO full models predicting recovery (vs. stable high) trajectories of probable anxiety (upper) and probable depression (lower). Variable importance less than 10 were omitted.

Table 3. Standardized coefficients for all nonzero predictors in LASSO Logistic Regression comparing stable low with stable high trajectories and comparing recovery with stable high trajectories

Note. All predictors were measured at baseline except measurement for personality (measured at the 4th follow up). AUCs of the four models were 0.86, 0.77, 0.73, and 0.61, respectively.

Predicting trajectories of anxiety

Relative to participants with stable high anxiety symptoms, those with stable low anxiety symptoms were less likely to be higher in neuroticism and openness, use hallucinogens, and have alcohol dependency symptoms in the past six months. They were also less likely to be the victims of violence, experience mother’s hostility or father’s remarriage, and live in the neighborhood with a higher price to buy a .38 mm gun. Participants in stable low trajectory were more likely to report stronger work orientation and had a father with grade school or less education.

Relative to participants in stable high trajectory, those in recovery trajectory were less likely to report lower education level, get a good grade at school (about half As and half Bs), and have more children. They were also less likely to experience violence, peer antisocial behavior, and have more friends being arrested or jailed. Participants in recovery trajectory were more likely to be Black, in a higher grade (9th–11th grade), have a stronger self-identity, use sedatives and hallucinogens in the past six months, and had a father with some college education.

Predicting trajectories of depression

Relative to participants in stable high trajectory, those with stable low trajectory were less likely to be Asian or other ethnic minority, higher in neuroticism, have drug dependency symptoms in the past six months, and earn more money per hour. They were also less likely to experience violence, mother’s hostility, father’s remarriage, close friends being in jail, and a chaotic environmental neighborhood. They were more likely to have strong work orientation and be convicted of 4th degree of felony. Relative to participants in stable high trajectory of depressive symptoms, those in recovery trajectory were more likely to have a nonincarcerated sentence, such as fines or restitution, probation, and nonincarcerated residential placement.

Discussion

This study aims to identify heterogeneity in psychological adaptation and its multilevel predictors among juvenile offenders with no previous detention history in the seven years following the first conviction of serious crime. Previous study of mental health trajectories treated all participants as homogeneous without identifying individual differences (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Padgaonkar, Galván, Frick, Steinberg and Cauffman2022). We reported some of the first evidence on three trajectories using Growth Mixture Modeling. The longitudinal study design over seven years with a total of 11 observation data points was optimal for detecting the variance and covariance of change in mental health outcomes (Rast & Hofer, Reference Rast and Hofer2014). Furthermore, most previous studies used selective risk factors and focused on a specific group without a coherent picture of mental health trajectories of juvenile offenders upon release. We considered potential risk factors across personal, relatioship, and contextual levels and used the LASSO regression model to address multicollinearity between predictors and model overfit and select the most important risk factors. The current findings could facilitate development of scalable prevention tools for adolescents involved with criminal justice system who are at increased risk of chronic psychopathology.

Consistent with our expectation and previous findings of the prototypical trajectories following stressful events (Galatzer-Levy et al., Reference Galatzer-Levy, Huang and Bonanno2018), three trajectories (stable low trajectory, stable high trajectory, and recovery) were identified for anxiety and depressive symptoms, in which the majority demonstrated a stable low trajectory (75.78%–75.96%) over the seven years. Predictors across person-, relationship-, and context-levels were all found to be associated with psychological resilience and chronicity of psychiatric symptoms. Some proportions of the juvenile offenders (<25%) demonstrated either recovery from or stable high and increasing clinically significant anxiety and depressive symptoms over time. This finding could be partially reflected by the nonlinear growth in internalizing symptoms among male adolescents following the first arrest – symptoms decreased initially followed by a significant increase over time (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Padgaonkar, Galván, Frick, Steinberg and Cauffman2022). While mental health recovery may occur naturally (Ranøyen et al., Reference Ranøyen, Lydersen, Larose, Weidle, Skokauskas, Thomsen, Wallander and Indredavik2018), involvement with criminal justice system could worsen the symptoms at the same time (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Padgaonkar, Galván, Frick, Steinberg and Cauffman2022). Our findings also added to the existing body of knowledge by suggesting cautions in interpreting common predictors such as gender, quality of romantic relationship, and parents’ substance abuse and mental illness with internalized psychopathology among juvenile offenders (Manning & Gregoire, Reference Manning and Gregoire2009). These demographic predictors could have limited associations with the progression of symptoms over time despite their concurrent positive associations with mental health problems.

The current results were consistent with Panter-Brick’s socioecological perspective that emphasized the importance of considering factors across micro to macro levels in explaining psychological resilience (Panter-Brick & Eggerman, Reference Panter-Brick, Eggerman and Michael2012). We identified different levels of factors of stable low trajectory. These protective factors are in line with previous empirical evidence. A study of 639 low-income African American adolescents in Chicago found that high self-esteem is associated with less delinquency and behavioral problems (substance abuse, sexual risk behaviors), more school engagement, and fewer mental health symptoms as measured by Brief Symptom Inventory (D. H. Kim et al., Reference Kim, Bassett, Takahashi and Voisin2018). Another longitudinal study of 323 Dutch youths revealed that self-concept clarity and anxiety/depressive symptoms reciprocally impacted each other over time (Van Dijk et al., Reference Van Dijk, Branje, Keijsers, Hawk, Hale and Meeus2014). Furthermore, perceived life goals (e.g., academic aspirations and expectations) could be inversely correlated with subsequent depressive symptoms as shown in a 1-year follow-up study among 3,343 13-year-old Swedish adolescents (Almroth et al., Reference Almroth, László, Kosidou and Galanti2018). Future rehabilitation programs should target at enhancing self-identity and self-efficacy among juvenile offenders.

Work orientation was found to be a protective factor in the present study, probably through motivating juvenile offenders to fulfill the role as productive and respected members of the community in their adulthood (Schaeffer et al., Reference Schaeffer, Henggeler, Ford, Mann, Chang and Chapman2014). This finding was consistent with previous evidence showing that career adaptability, denoting competence and adjustment to in career context, predicted lower odds of mental health problems and higher odds of life satisfaction (Ginevra et al., Reference Ginevra, Magnano, Lodi, Annovazzi, Camussi, Patrizi and Nota2018). In addition, compared with adolescents in community settings, juvenile offenders could have poor education achievement and thus inadequate preparation to enter the workforce (Roos, Reference Roos2006). However, contrary to our expectation, committing 4th degree felony was a predictor of stable low trajectory of depression. Previous studies suggested that the association between depression and delinquency is bidirectional while delinquency could be seen as a risk factor for subsequent depression rather than anxiety (Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Colins and Andershed2019). Future research may investigate this association.

Transdiagnostic factors predicting chronic anxiety and depression

Neuroticism, substance abuse problems, exposure to violence, mother's hostility, and father’s remarriage were found to be transdiagnostic factors for persistent probable anxiety and depression among the present sample of juvenile offenders in the 7-year follow-up. This was consistent with previous evidence on the stronger association of neuroticism relative to other traits in the five-factor model with internalized mental disorders (Kotov et al., Reference Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt and Watson2010; A. L. Williams et al., Reference Williams, Craske, Mineka and Zinbarg2021). Our findings suggest the clinical validity of neuroticism in forensic psychiatry especially the long-term progression of probable anxiety and depression during juvenile offenders’ transition from adolescence to adulthood. Substance abuse was another transdiagnostic factor predicting chronic anxiety and depression among juvenile offenders. The strong association between drug abuse, anxiety, and depression was supported by the high prevalence of comorbid illicit drug use disorder with anxiety disorders and major depression relative to other psychiatric conditions (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Cleary, Sitharthan and Hunt2015). Our findings on juvenile delinquents also replicated previous evidence on the prospective prediction of early exposure to violence and psychopathology (anxiety and depression) among adolescents (Haahr-Pedersen et al., Reference Haahr-Pedersen, Ershadi, Hyland, Hansen, Perera, Sheaf, Bramsen, Spitz and Vallières2020; LeMoult et al., Reference LeMoult, Humphreys, Tracy, Hoffmeister, Ip and Gotlib2020; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Hammen, Brennan, Najman and Bor2005) and further suggested its relevance to the persistence of the two psychiatric disorders.

Apart from personal risk factors, family relations of juvenile offenders could predict persistent probable anxiety and depression. The LASSO regression model included different types of parental marital statuses and parent-child relationships and selected two that were the most predictive of internalized disorders of juvenile offenders, namely mother’s hostility and father’s remarriage. This finding was consistent with previous evidence on the long-term impact of parental remarriage on children’s mental health and parent-child relation (O’Gara et al., Reference O’Gara, Zhang, Padilla, Liu and Wang2019). The findings also suggested the importance of considering the marital status of father figure in predicting children’s internalized symptoms during the age of 16–22 years (Tulisalo & Aro, Reference Tulisalo and Aro2000). The role of parenting style in shaping internalized problems of juvenile offenders has been replicated in several previous longitudinal studies across different regions (Beckmann, Reference Beckmann2021; A. G. Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Ozbardakci, Fine, Steinberg, Frick and Cauffman2018; Traver et al., Reference Traver, Dallaire, Frick, Steinberg and Cauffman2022; L. R. Williams & Steinberg, Reference Williams and Steinberg2011). Our findings additionally highlighted the importance of mother figure, especially mother’s hostility in predicting chronic anxiety and depression. Family-based intervention could ameliorate psychological distress among juvenile delinquents who experienced mother’s hostility and/or father’s remarriage (Dopp et al., Reference Dopp, Borduin, White II and Kuppens2017).

Diagnostic specific factors predicting chronic anxiety and depression

Among the list of personal, relationship, and contextual predictors for stable high anxiety and depression, we observed that chronically high levels of depressive symptoms were predicted by more fundamental, longstanding risk factors including race (Asian and other ethnic minority), criminal surroundings (friends being jailed), and living environment (chaotic neighborhood). On the contrary, persistent and increasing anxiety symptoms were predicted by personality and behavioral factors, for example, lower openness to experience (personality), hallucinogen use in the past six months, and alcohol dependance symptoms in the past six months, suggesting that individualized intervention approach could be more suitable for addressing persistent anxiety symptoms than depressive symptoms of juvenile offenders. It is worth noting that father’s education level could have distinctly different predictions on the trajectories of anxiety symptoms. Father’s education level of grade school or less was associated with decreased risk for chronic anxiety symptoms, whereas father’s college education was associated with an increased probability of recovery from anxiety symptoms. This interesting finding replicated a recent experimental evidence on the inverse association between parental education level and children’s cortisol response to acute stress (Parenteau et al., Reference Parenteau, Alen, Deer, Nissen, Luck and Hostinar2020). However, when comparing juveniles in stable high trajectories with recovery trajectories of anxiety symptoms, we found that high education level of father could facilitate juvenile delinquents’ recovery from prior significant anxiety symptoms. A recent study of 1,057 adolescents in grades 7–12 reported that fathers’ education but not mothers’ was positively related to children’s self-compassion, which linked to better mental health (Bluth et al., Reference Bluth, Park and Lathren2020; Trompetter et al., Reference Trompetter, de Kleine and Bohlmeijer2017). There is evidence showing that adolescents whose fathers had college education reported higher levels of self-compassion compared with adolescents with fathers of lower education levels (Bluth et al., Reference Bluth, Park and Lathren2020).

Targets for prevention and intervention efforts: recovery factors

Age of onset of anxiety disorders has been found to vary across childhood and adolescence, for example, specific phobia in early to middle childhood and social phobia in early to middle adolescence (Rapee et al., Reference Rapee, Schniering and Hudson2009). Our analysis of the predictors of those in recovery vs. stable high trajectories could inform intervention and prevention efforts. The current study supplemented previous evidence by investigating ethnic differences in long-term trajectories of psychiatric symptoms. White juveniles have been found to have a higher risk of developing psychiatric disorders (Angold et al., Reference Angold, Erkanli, Farmer, Fairbank, Burns, Keeler and Costello2002). On the contrary, Black juvenile delinquents in high grade (9th–11th grade) could show high levels of anxiety symptoms at the outset but they are more likely to recover in long term compared with other ethnicities. Compared with high school graduates, juvenile delinquents who were still studying in high grade were more likely to recover from persistent anxiety symptoms. Compared with graduates, adolescents in high school were still closely monitored by school and family and therefore more likely to receive appropriate interventions and/or treatments for their emotional problems. The findings suggest that the optimal treatment window could be before high school graduation.

Counterintuitively, sedatives and hallucinogens use in the past six months predicted the recovery trajectory of anxiety symptoms. This may relate to the treatment effects of these two drugs for anxiety disorders. Juveniles may use psychoactive substance, particularly sedatives and hallucinogens to reduce anxiety symptoms because anxiety disorders often occur in adolescence, such as social phobia in adolescence and obsessive-compulsive disorder in the middle to late adolescence (Rapee et al., Reference Rapee, Schniering and Hudson2009, Reference Rapee, Oar, Johnco, Forbes, Fardouly, Magson and Richardson2019; Valentiner et al., Reference Valentiner, Mounts and Deacon2004). This could reflect possible self-medication and the potential problem of psychiatric and substance abuse comorbidities despite the benefit on anxiety symptoms. More longitudinal research is needed to test the effect of psychoactive on the trajectories of mental disorders among juvenile delinquents.

Non-incarceration (fines or restitution, probation, nonincarcerated residential placement) was uniquely related to juveniles’ recovery from depressive but not anxiety symptoms. This highlighted the treatment effects of non-incarceration for depressive symptoms of serious juvenile offenders and replicated previous evidence demonstrating that community-based intervention practices should be adopted to achieve the best outcomes for juveniles (Lambie & Randell, Reference Lambie and Randell2013).

Factors that were inversely associated with recovery from chronic anxiety suggested that intervention programs must be tailored to individuals’ social ecology. Juveniles in low grade (6th grade or less-8th grade) were less likely to recover therefore, clinicians should pay attention to those early-onset anxiety symptoms. Individuals who got about half As and half Bs, had more children and antisocial peers, and witnessed violence were less likely to recover. This finding may reflect a group of students who were smart but lived in a deprived environment characterized by violence and crime. The contradiction between individuals’ talents and living environment may lead to chronic anxiety symptoms (Santiago et al., Reference Santiago, Wadsworth and Stump2011).

Our findings were in line with the developmental ecological perspective on longitudinal trajectories of juveniles’ mental health. Across three levels of predictors (person, relationship, and context levels), our findings highlighted the importance of proximal socio-ecological contexts, especially family context. Dysfunctional family systems, such as father remarriage and mother hostility, can differentially predict stable-high trajectories. This can be elucidated by the belongingness theory, which suggested that the inability to find belongingness with one’s family could increase the risk of internalized symptoms for youths involved with juvenile justice system (Stone et al., Reference Stone, Poquiz, Fite and Pederson2022). Family context factors may also interact with person-level factors, such as personality of children (e.g., neuroticism), and together, put adolescents at risk of violence, which might have a ripple effect on the development of chronic anxiety and depression. Previous evidence demonstrated the effect of family disruption on children’s personality development (Prevoo & ter Weel, Reference Prevoo and ter Weel2015). Specifically, we found that the association between father’s remarriage and children’s internalized symptoms could potentially be driven by children’s high neuroticism. Therefore, the present findings suggested that special attention is needed on the mental health of juvenile delinquents who experienced father’s remarriage and are high in neuroticism.

That family disruption (e.g., father’s remarriage) interacted with violence exposure replicated previous evidence on higher victimizations among youths from stepfamilies relative to those living with two biological parents (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Finkelhor and Ormrod2007). The finding was also in line with previous evidence on the association between parental instability and secondary exposure to violence among children living in a neighborhood with high crime rates (Stritzel et al., Reference Stritzel, Smith Gonzalez, Cavanagh and Crosnoe2021). Family-based intervention should be implemented with a focus on comprehending and addressing family contexts of their patients and the potential interaction with personality and violence exposure, with the ultimate goal of preventing chronic psychiatric symptoms among juvenile offenders.

Risk factors of recovery trajectories revealed the interaction between peer context factors and person-level factors. We found that juveniles affiliated with antisocial peers were more likely to achieve low education levels and have more children, with these factors inversely related to recovery from chronic anxiety. Our findings were consistent with the well-established impact of antisocial peer contexts on anxiety through its interaction with early sexual experience and school dropout. Involvement with deviant peers was identified as a significant risk factor for school dropout in a recent meta-analysis (Gubbels et al., Reference Gubbels, van der Put and Assink2019). In a longitudinal study of twin adolescents, a reciprocal relationship was found between antisocial peers and engagement with early sexual experience due to their shared environmental influence (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Durbin, Heitzeg, Iacono, McGue and Hicks2021).

Among a list of sociodemographic resilience factors, our findings suggested the potential interaction between race, education level, and father’s education level for recovery from anxiety. Even though Black juveniles are overrepresented in the US (Abrams et al., Reference Abrams, Mizel and Barnert2021), juveniles whose fathers with a college education may be more likely to achieve a higher education level, ultimately protecting them from developing chronic anxiety. This is consistent with previous evidence demonstrating the positive relationship between father education and children’s academic achievement (Muhammad, Reference Muhammad2015), and the predictive utility of father’s education level but not mother’s for children’s anxiety among high school students (Aiazzam et al., Reference Aiazzam, Abuhammad, Abdalrahim and Hamdan-Mansour2021). One plausible explanation might be that well-educated fathers can provide more resources to maintain children’s educational opportunities and facilitate their adaptive coping with stress (Reiss et al., Reference Reiss, Meyrose, Otto, Lampert, Klasen and Ravens-Sieberer2019).

Limitations and conclusion

Several limitations should be considered in evaluating the current findings. First, the data was collected between 2000 (first baseline interview) and 2010 (last follow-up interview), which occurred a decade ago. However, some contextual factors, such as the popularity of using hallucinogen and gun accessibility remain essential concerns in the US nowadays. A national survey of trends in US hallucinogen use from 2002 to 2019 showed that since 2002, hallucinogen use in the US has decreased among adolescents but increased in adults (Livne et al., Reference Livne, Shmulewitz, Walsh and Hasin2022). The finding of hallucinogen use being a risk factor for developing chronic anxiety among juvenile offenders should be interpreted with caution by taking into account the current situation of decreased hallucinogen use among adolescents. Second, class numbers might not be accurately identified due to nonnormal distribution, intercept effect size, and group distribution, although we have excluded small classes and found reasonably large intercept effect sizes. Third, substance dependency was measured by counting the presence of symptoms. There is a possibility that participants might endorse many low-frequency dependency symptoms and many high-frequency dependency symptoms with the same score even though they would represent different ends of the substance use spectrum. Fourth, the current study focused on offenders who were convicted of a felony because of previous evidence on the positive link between the severity of offense and mental ill health. Our findings might not be generalized to juvenile offenders who committed misdemeanors or felony convicts who had been incarcerated before. Fifth, participants were not at the same age at baseline, although age did not significantly predict any trajectories.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study demonstrated the mental health needs of juvenile offenders in detention. Mental ill health could be associated with increased risks of reoffending, behavioral disturbance, substance misuse, and risky sexual behaviors in adulthood over time. This study identified multilevel predictors of the three prototypical trajectories of psychological vulnerability and resilience and thus pointed to feasible directions for developing holistic intervention and rehabilitation for reducing the risk of reoffending and other behavior problems among juvenile offenders.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579423000755

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. WK Hou was supported by General Research Fund (18600320), Research Grants Council, University Grants Committee, Hong Kong SAR, China. The funding source was not involved in the study design, data analysis or interpretation, or preparation/submission of this manuscript.

Competing interests

None.