Introduction

Adolescence is regarded as a window of vulnerability for developing psychopathology, due to the many changes adolescents have to cope with (Adriani & Laviola, Reference Adriani and Laviola2004; Roberts & Lopez-Duran, Reference Roberts and Lopez-Duran2019). Developmental changes in the structure of the social brain (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Lalonde, Clasen, Giedd and Blakemore2014) occur with potential hormone effects on brain development (Lynne et al., Reference Lynne, Metz, Graber, Wright and Hallquist2020). A significant increase in psychopathology was associated with maturation (Ullsperger & Nikolas, Reference Ullsperger and Nikolas2017) and simultaneously changing social contexts. In addition to the challenges that come with physical maturity, the changed body image, and the changing relationships with parents and peers (Beyers & Seiffge-Krenke, Reference Beyers and Seiffge-Krenke2007; Littleton & Ollendick, Reference Littleton and Ollendick2003; Smetana, Reference Smetana2010), the transitional period is complicated by multiple sources of life stress including school underperformance, poor peer relations, family conflicts, economic strain, and future uncertainty (Persike & Seiffge-Krenke, Reference Persike and Seiffge-Krenke2016; Seiffge-Krenke et al., Reference Seiffge-Krenke, Persike, Chau, Hendry, Kloepp, Terzini-Hollar, Tam, Naranjo, Herrera and Menna2012; Wadsworth et al., Reference Wadsworth, Rieckmann, Benson and Compas2004). Exposure to acute and chronic stressful events and adversity is one of the most potent risk factors for psychopathology during adolescence (Cicchetti & Walker, Reference Cicchetti and Walker2003; Roberts & Lopez-Duran, Reference Roberts and Lopez-Duran2019).

It is therefore not surprising that epidemiological research substantiated quite high levels of psychopathology in normative samples (Ivanova et al., Reference Ivanova, Achenbach, Rescorla, Dumenci, Almqvist, Bilenberg, Bird, Broberg, Dobrean, Döpfner, Erol, Forns, Hannesdottir, Kanbayashi, Lambert, Leung, Minaei, Mulatu, Novik and Verhulst2007), for both internalizing and externalizing symptoms of adolescents in many countries of the world (Rescorla et al., Reference Rescorla, Ivanova, Achenbach, Begovac, Chahed, Drugli, Emerich, Fung, Haider, Hansson, Hewitt, Jaimes, Larsson, Maggiolini, Marković, Mitrović, Moreira, Oliveira, Olsson and Zhang2012). But there is also an increase in psychopathological symptoms at a clinical level. Many symptoms appear for the first time during adolescence like, e.g., personality disorders or substance use (Paus et al., Reference Paus, Keshavan and Giedd2008); other symptoms intensify (e.g., depression), and many continue into emerging adulthood (Ludwig et al., Reference Ludwig, Graf von der Schulenburg and Greiner2018; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Roberts and Xing2007). Reviews of trends in psychopathology across adolescence showed increases in rates of depression, panic disorders, agoraphobia, and substance abuse, with anxiety disorders and depression showing continuity toward emerging adulthood (Costello et al., Reference Costello, Copeland and Angold2011). The 10-year longitudinal study from Hofstra et al. (Reference Hofstra, van der Ende and Verhulst2001) further substantiated that 29% of the clinical non-conspicuous adolescents developed symptoms at a subclinical level, which, if untreated, lead to severe psychopathology in the following years.

This is especially true for internalizing symptoms such as depression and anxiety, which are easily overlooked by caregivers and clinicians (Varley, Reference Varley2002). Epidemiologic studies indicate that the prevalence of depression rises from approximately 1–2% in childhood to the adult levels of 6–8% by the end of the adolescent years (Kovacs et al., Reference Kovacs, Obrosky and George2016); earlier onset is associated with longer episode duration, increased comorbidity, suicidality, and hospital admission (Kovacs et al., Reference Kovacs, Obrosky and George2016; Neufeld et al., Reference Neufeld, Dunn, Jones, Croudace and Goodyer2017). Anxiety symptoms are also widely prevalent in adolescents (Gosmann et al., Reference Gosmann, Vaz, DeSousa, Koller, Pine, Manfro and Salum2016; Polanczyk et al., Reference Polanczyk, Salum, Sugaya, Caye and Rohde2015) and manifest when untreated, with high stability over 5 years (Laucht et al., Reference Laucht, Esser and Schmidt2000). Externalizing disorders are relatively common in adolescents as well, affecting about 4.6% of young people (Sadler et al., Reference Sadler, Vizard, Ford, Marchesell, Pearce, Mandalia, Davis, Brodie, Forbes and Goodman2018). Delinquency, juvenile offending, and antisocial behavior may have an early start (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt1993), but may also emerge during adolescence (Dishion & McMahon, Reference Dishion and McMahon1998; Racz & McMahon, Reference Racz and McMahon2011), which, when untreated, increases the risk of recurrence, resulting in further problem behavior such as substance use or risky sexual behaviors.

Considering the negative effects on health and future maladaptive functioning (Luthar & Cicchetti, Reference Luthar and Cicchetti2000), these disorders require professional psychotherapeutic treatment. Different forms of psychotherapy vary in their suitability for patients with different diagnoses and different ages. The rationale for treating internalizing disorders such as depression and anxiety disorders with psychodynamic therapy is the understanding that they are primarily affective disorders (Midgley et al., Reference Midgley, Mortimer, Cirasola, Batra and Kennedy2021; Seiffge-Krenke, Reference Seiffge-Krenke2020a; Shapiro & Esman, Reference Shapiro and Esman1985), and that the enormous social, emotional, and cognitive gains of adolescents (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Lalonde, Clasen, Giedd and Blakemore2014; Smetana, Reference Smetana2010) make a treatment with a focus on mentalization, emotion regulation, and working through conflicts in close relationships (Ablon et al., Reference Ablon, Levy and Katzenstein2006; Bateman & Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009; Shapiro & Esman, Reference Shapiro and Esman1985) particularly suitable for them. Basic assumptions of psychodynamic therapy are the existence of internalized unconscious conflicts, that symptoms have meaning, and that transference-based interventions are helpful (Kernberg et al., Reference Kernberg, Ritvo and Keable2012; Shapiro & Esman, Reference Shapiro and Esman1985). Achieving a shared understanding of the origins and effects of negative emotions and to support autonomy were guiding principles in therapy with adolescents from its beginning (Freud, Reference Freud1958, Reference Freud1965). Offering insight into maladaptive behaviors, connecting these behaviors with underlying feelings, and pointing out defensive nature helps adolescents to resort less to self-destructive behaviors and acting out. Psychodynamic treatment principles with adolescent patients have changed slightly over time since this treatment was invented by Anna Freud and Melanie Klein, due to changes in the psychopathology of the patients (Seiffge-Krenke, Reference Seiffge-Krenke2017). In recent years, working on deficits in emotion regulation, regulating interpersonal relations, and in developing self-reflection and empathy with others, became more important (Seiffge-Krenke, Reference Seiffge-Krenke2020b) making this treatment suitable and effective for a variety of adolescent disorders from the internalizing and externalizing spectrum (Salzer et al., Reference Salzer, Cropp, Jaeger, Masuhr and Streeck-Fischer2014; Weitkamp et al., Reference Weitkamp, Daniels, Baumeister-Duru, Wulf, Romer and Wiegand-Grefe2018).

Although psychodynamic therapy in children and adolescents is one of the most frequently used techniques (Weisz & Jensen, Reference Weisz and Jensen2001), the small number of efficacy studies is striking (Fonagy, Reference Fonagy2015; McCarty & Weisz, Reference McCarty and Weisz2007; Weisz et al., Reference Weisz, Kuppens, Ng, Eckshtain, Ugueto, Vaughn-Coaxum, Jensen-Doss, Hawley, Krumholz Marchette and Chu2017) compared to many studies reporting outcomes of cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy (Herbert et al., Reference Herbert, Gaudiano, Rheingold, Moitra, Myers, Dalrymple and Brandsma2009; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer and Fang2012; Shirk et al., Reference Shirk, Kaplinski and Gudmundsen2009), but also compared to research on psychodynamic treatment with adult patients (Chorpita et al., Reference Chorpita, Daleiden, Ebesutani, Young, Becker, Nakamura, Phillips, Ward, Lynch and Trent2011). A review of randomized controlled trials (RCT) on treated children and adolescents demonstrated that only 1.7% had studied a psychodynamic treatment approach (Weisz et al., Reference Weisz, Doss and Hawley2005). However, empirical evidence from RCT studies does not necessarily yield comparable results in terms of effectiveness under practical conditions (Leichsenring, Reference Leichsenring2004), which include less selected patients (e.g., regarding existing comorbidities), limited or no possibility of randomized allocation to different therapy arms, and longer therapies. Reviews continue to show a high demand for long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy studies (Abbass et al., Reference Abbass, Rabung, Leichsenring, Refseth and Midgley2013; Midgley et al., Reference Midgley, O’Keeffe, French and Kennedy2017, Reference Midgley, Mortimer, Cirasola, Batra and Kennedy2021; Midgley & Kennedy, Reference Midgley and Kennedy2011). Current evidence is particularly sparse when it comes to adolescent patients and long-term treatment as delivered in routine practice, emphasizing the need for effectiveness studies with high external validity (Midgley et al., Reference Midgley, Mortimer, Cirasola, Batra and Kennedy2021), that helps in translating research into clinical practice. The developmental background of patients in this age group makes them particularly suitable for the use of long-term psychodynamic therapy. However, there might be growth and change also in nontreated adolescents due to developmental progression which should be considered when assessing the effects of psychotherapy.

Present study and research questions

The present study draws conceptually on theory and research showing that the adolescent period can be equally regarded as a window of vulnerability in which several mental disorders emerge, or intensify (Adriani & Laviola, Reference Adriani and Laviola2004), but also as a key period of growth with positive change in mental health (Wekerle et al., Reference Wekerle, Waechter, Leung and Leonard2007). We focused on a comparatively narrow age window (i.e., 12–18 years), which is considered particularly critical for the development of psychopathology but also has the potential for growth and change (Lynne et al., Reference Lynne, Metz, Graber, Wright and Hallquist2020).

Regarding adolescents with severe psychopathology, studies on efficacy, and effectiveness of treatment tend to focus on single disorders and do not distinguish between distinct domains of adolescent psychopathology, like externalizing and internalizing symptoms and their co-occurrence (Angold et al., Reference Angold, Costello and Erkanli1999), although comorbidity is the rule in the transitional period (Seiffge-Krenke, Reference Seiffge-Krenke2020b). Most longitudinal studies covered short periods of treatment including small samples, sampling children of varying ages and developmental stages (Midgley et al., Reference Midgley, Mortimer, Cirasola, Batra and Kennedy2021). In the meta-analysis by Weisz et al. (Reference Weisz, Kuppens, Ng, Eckshtain, Ugueto, Vaughn-Coaxum, Jensen-Doss, Hawley, Krumholz Marchette and Chu2017) covering 50 years of research, only 30% of the patients were adolescents, the treatment duration was relatively short (about 17 h), and included only a very small number of studies based on psychodynamic therapies (29 of 444). There were no significant differential effects of different forms of treatment. Earlier comparative meta-analyses (Abbass et al., Reference Abbass, Rabung, Leichsenring, Refseth and Midgley2013) did not reveal different effects between cognitive behavioral therapy and psychodynamic therapy for diverse disorders. This meta-analysis also lumped together children and adolescents and covered rather short periods (10–40 sessions). Consequently, developmental informed research questions about psychopathology and growth could not be answered.

Long-term intensive therapeutic work is often necessary to reduce severe internalizing and externalizing symptoms, reface the challenges of this development phase, and “put development back on track” (Freud, Reference Freud1958, p. 260). Of note, adolescents’ evaluation of their psychodynamic treatment (Løvgren et al., Reference Løvgren, Røssberg, Nilsen, Engebretsen and Ulberg2019) showed that they value that the long-term treatment gave them time to develop. Longer treatments are more difficult to examine in randomized controlled studies (Midgley et al., Reference Midgley, Ansaldo and Target2014; Woll & Schönbrodt, Reference Woll and Schönbrodt2020). For adolescents with clinically relevant symptomatology, randomization to a nonintervention group is particularly unethical and sometimes even not feasible due to treatment requirements within the applicable health care system. However, not all adolescents who experience stress and adversity develop psychopathology (Compas et al., Reference Compas, Jaser, Bettis, Watson, Gruhn, Dunbar, Williams and Thigpen2017). Similarly, the high rate of spontaneous remission found in adolescent patients may indicate positive growth (Seiffge-Krenke, Reference Seiffge-Krenke2020b). Psychodynamic treatment may promote individual competence, but also adolescents from the nontreatment group confronted with age-specific stressors may develop competencies to shift their development in a positive way (Luthar & Cicchetti, Reference Luthar and Cicchetti2000). Consequently, examining longer time intervals and including control groups with different levels of stress is recommended when analyzing the effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy in comparison to the normative developmental progression of adolescents.

Multinational epidemiological studies comparing adolescents’ self-report in normative samples in 44 countries yielded similar epidemiological findings (Rescorla et al., Reference Rescorla, Ivanova, Achenbach, Begovac, Chahed, Drugli, Emerich, Fung, Haider, Hansson, Hewitt, Jaimes, Larsson, Maggiolini, Marković, Mitrović, Moreira, Oliveira, Olsson and Zhang2012) with mean levels close to clinical cutoffs, particularly for females, suggesting that the challenges of this developmental period are quite demanding. Adolescents from a normative sample are therefore considered a meaningful control group. It also makes sense to compare intraindividual change of internalizing and externalizing symptoms (over time) of adolescents in treatment to the development of adolescents with a chronic somatic condition, as they share a certain level of strain and daily constraints and usually have to adhere to some kind of treatment regimen with regular medication and medical checkups (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Gibson and Franck2008). Due to the normative stressors and developmental tasks all adolescents are confronted with, adolescence can represent a difficult time, e.g., for those having juvenile diabetes, leading to a worsening of glycemic control and high levels of psychopathology (Seiffge-Krenke, Reference Seiffge-Krenke2001; Silverstein et al., Reference Silverstein, Klingensmith, Copeland, Plotnick, Kaufman, Laffel, Deeb, Grey, Anderson and Holzmeister2005), especially to depression, anxiety, and eating disorders (Anderson, Reference Anderson2010; Dantzer et al., Reference Dantzer, Swendsen, Maurice-Tison and Salamon2003; Kanner et al., Reference Kanner, Hamrin and Grey2003).

A further lacuna in research concerns gender-specific pathways in internalizing and externalizing psychopathology in clinical and comparison groups. A large body of research seems to suggest that girls generally exhibit more internalizing problem behavior and boys exhibit more externalizing problems (Bettge et al., Reference Bettge, Wille, Barkmann, Schulte-Markwort and Ravens-Sieberer2008; Rescorla et al., Reference Rescorla, Ivanova, Achenbach, Begovac, Chahed, Drugli, Emerich, Fung, Haider, Hansson, Hewitt, Jaimes, Larsson, Maggiolini, Marković, Mitrović, Moreira, Oliveira, Olsson and Zhang2012). While the early adolescent period is considered as particularly stressful for early maturing girls (Lynne et al., Reference Lynne, Metz, Graber, Wright and Hallquist2020), a meta-analysis showed robust early pubertal timing effects for both genders across all domains of psychopathology (Ullsperger& Nikolas, Reference Ullsperger and Nikolas2017). Further, the impact of time and developmental progression on different outcomes is unclear. Several studies demonstrated that externalizing and internalizing behaviors follow different developmental trajectories in different groups (Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2014; van der Valk et al., Reference van der Valk, Spruijt, Goede, Maas and Meeus2005). It is yet unclear whether intraindividual change trajectories for males or females differ across time and age, both in treatment and nontreatment samples. Finally, research is limited by including only one reporter. Earlier evidence substantiated significant discrepancies between youth and parent-reported psychopathology in children and adolescents (Salbach-Andrae et al., Reference Salbach-Andrae, Klinkowski, Lenz and Lehmkuhl2009). As parents frequently initiate the start of therapy (Seiffge-Krenke, Reference Seiffge-Krenke2020b) and are involved in the medical and psychotherapeutic treatment, it is recommendable to also assess their perception of the psychopathology and its change over time.

To conclude, current research is characterized by a lack of empirical evidence on the effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy in adolescent patients, problems in the selection of adequate comparison groups, (too) short-time intervals, the neglect of potential age- and gender-specific pathways, and the limitation to only one data source. Our research aims to be innovative as it draws from a developmental psychopathology perspective and includes growth as well as pathology. This study intends to analyze the effectiveness of psychodynamic treatment in reducing adolescent patients’ internalizing and externalizing symptomatology by comparing treatment-related changes with time-related changes in two comparison samples, healthy adolescents, and adolescents with diabetes. We also aimed at identifying age- and gender-specific trajectories in internalizing and externalizing symptoms in the three groups over the course of 2 years. Since mothers usually know their children better than fathers (Steinberg, Reference Steinberg2014) and are more often involved in everyday matters, we included the adolescent and the mother’s report of internalizing and externalizing symptomatology. Our research and analyses were guided by the following research questions:

RQ1: Does psychodynamic therapy in treated adolescents lead to a significant reduction in internalizing and externalizing symptoms, both over time, and compared to the developmental progression of two nontreated comparison groups: healthy adolescents and adolescents with diabetes?

RQ2: Are there gender- and age-specific pathways in symptom severity and/or within-person change for internalizing and externalizing symptoms?

RQ3: Do mothers of treated and nontreated adolescents perceive their child’s internalizing and externalizing symptom severity and/or within-person change differently than their child and are there gender-specific biases? If so, does this discrepancy between mothers and their child change over time and affect therapy trajectories?

Method

Study design and participants of the treatment sample

For the treatment sample, n = 303 adolescent patients (46.9 % male; mean age at the beginning of treatment: M = 12.06 years, range: 12–18, SD = 2.86) were assessed at the beginning of therapy (T1), after the first year (T2), and after the second year (T3). A flow chart of the treatment and control samples (described below) is provided in Online Supplement ESM 7. The data were collected between 2005 and 2015 in an outpatient training clinic (Seiffge-Krenke & Posselt, Reference Seiffge-Krenke and Posselt2021; Seiffge-Krenke, Reference Seiffge-Krenke2001). Referrals were made by the parents or health professionals. Referred adolescents between 12 and 18 years with clinically relevant symptoms (i.e., requiring psychotherapeutic treatment according to applicable treatment guidelines within the German health care system) were consecutively assessed for eligibility and included in the study given eligibility and informed consent. Adolescents with borderline psychopathology, psychotic symptoms, and significant risk for suicide were excluded and referred to inpatient treatments. The study received full Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Mainz, Germany.

Prior to study inclusion, written informed consent was obtained from patients and their parents. Included patients needed to fulfill the requirements for psychotherapeutic treatment within the German health care system, including ICD-10 diagnoses. Diagnoses were initially based on an independent diagnostician who conducted an interview; all diagnoses were peer-reviewed in the weekly meetings of all therapists within the outpatient clinic. The most frequent ICD-10 diagnoses were: F32 depression (22.4%), F40 anxiety disorders (20.1%), F43 stress disorders (19.8%), and F93 emotional disorders of childhood (14.3%). Most rare disorders were F42 obsessive-compulsive disorder (1.9%), F44 dissociative disorders (1.8%), and F98 enuresis (0.6%). Suitability for psychodynamic treatment was assessed by three diagnostic interviews with the adolescent and one interview with the parents, including the history of the symptoms, the developmental history of the patient, his or her relationships, and the family background. The interviews include a psychodynamic diagnostic evaluation (Resch et al., Reference Resch, Romer, Schmeck and Seiffge-Krenke2017) to assess the level of symptom burden, secondary gains, psychotherapy motivation, the capacity to reflect on inner states, potential conflicts, and the resources of the patient and his or her family. Participants and their respective families came from broad socioeconomic strata (46% middle class; 49% of mothers were employed) and family/household structures (44% of patients lived in two-parent families; 33% in single parent, 23% in step- or foster families or residential homes). The average number of siblings was n = 1.67 per family.

Psychodynamic Psychotherapy: Aims, treatment phases, and interventions

Adolescents in treatment received weekly 50-min sessions of psychodynamic therapy, on average n = 85.9 sessions over approximately 2 years. As described in the introduction, psychodynamic treatment goals do not only target the reduction of symptoms but try to promote patients’ insight into unconscious conflicts and explicitly address structural impairments in patients’ self and interpersonal functioning. (For an overview about the conceptual and empirical overlap between structural impairments from a psychodynamic perspective and personality functioning as defined in the Alternative Model of Personality Disorder in DSM-5 and the PD chapter in ICD-11, see e.g., Zimmermann et al., Reference Zimmermann, Müller, Bach, Hutsebaut, Hummelen and Fischer2020). Thus, the treatment entails both a focus on increasing insight in repetitive patterns of relating to self and others and a focus on improving mentalization. Specific interventions of psychodynamic treatment include support, helping with mentalization and understanding that symptoms have meaning, but also include confrontation, clarification, and interpretations of dysfunctional behaviors, thoughts, and feelings and their origin. The interventions involve also working with transference in those patients where it seems appropriate. Together, these interventions are aimed at the patient’s insight into one’s behavior, feelings, and conflicts and thus positively influence the psychopathology in the long run. During the first year (approximately 40 sessions), the psychodynamic treatment focus on the establishment of a positive therapeutic relationship, of basic trust, and an effective working alliance to work on the insight into maladaptive behaviors, thoughts, and feelings (Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist and Target2018). The ways adolescents avoid difficult experiences and contradictory feelings are explored and defense mechanisms are interpreted gradually (Freud, Reference Freud1958). In later phases (approx. 40 sessions, second year of treatment), working through recurrent themes and a focus on autonomy are important (Seiffge-Krenke, Reference Seiffge-Krenke2020b). Therapists place central importance on adolescents’ recurrent emotional and interpersonal experiences, along with early memories, and encourage the adolescent to replace maladaptive defenses with more mature ones. He or she also draws attention to the therapeutic relationships (e.g., highlight the adolescents’ emotional and interpersonal pattern that finds reflection also in the transference dynamic) and encourages autonomy both within and outside therapy.

Therapists, supervisors, and clinical adherence to the treatment model

Each study therapist (n = 55; 14.3% male) treated about five patients (m = 5.61; SD = 3.47; range: 1–14) and underwent a three-to-five-year long postgraduate, state-licensed training in psychodynamic therapy. About 50% of therapists had prior clinical experience between one and three years, with 30% having less than one year, and 20% with 3–5 years. To establish that the interventions were delivered as planned (Leichsenring et al., Reference Leichsenring, Salzer, Hilsenroth, Leibing, Leweke and Rabung2011) we used clinical adherence with mandatory supervision every fourth therapy session, conducted by licensed supervisors with at least ten years of clinical experience. Supervisors had to go over each hour to see whether the treatment was conducted as planned. They pay attention to whether the therapeutic relationship reflects the relational challenges of this age group (Can & Halfon, Reference Can and Halfon2021), and if the interventions are individualized (e.g., whether the therapists use the right balance between supportive and interpretative statements depending on diagnosis, age, and treatment stage, Kernberg et al., Reference Kernberg, Ritvo and Keable2012). Supervisors helped the therapists to find unconscious material, and to relate it to the patient’s experience both within and outside therapy. Further, the supervisor helps to understand, that symptoms have meaning, and that transference- and countertransference experiences are critical.

Participants of the nontreatment sample

Two nontreatment samples from the German Longitudinal Study on Juvenile Diabetes (Luyckx et al., Reference Luyckx, Seiffge-Krenke and Hampson2010, Reference Luyckx, Seiffge-Krenke, Missotten, Rassart, Casteels and Goethals2013; Seiffge-Krenke, Reference Seiffge-Krenke2001) were included in this study (cf. Online Supplement 7). The study investigated various developmental parameters over eight yearly assessments. For this study, scores of internalizing and externalizing symptoms of the first three yearly measurement occasions (study year 1–3) were taken, since this represents the start of the assessment period and mirrors the duration of the psychodynamic therapy of the treatment sample. The first sample consisted of n = 109 adolescents with juvenile diabetes (53% male; age M = 13.77, range: 12–16 years; SD = 1.41) and their respective mothers. The second sample consisted of n = 119 healthy adolescents (44% male; age: M = 13.97 [range: 12–17] years; SD = 1.25) and their respective mothers. Taken together, the nontreated sample consisted of a total of n = 228 adolescents (48.3% male; age M = 13.87, range: 12–17 years; SD = 1.33) and their mothers.

All adolescents with juvenile diabetes (n = 109) were recruited from 17 pediatric health care services across two German cities. Mean duration of diabetes at study inclusion (first assessment) was 4.79 years (SD = 2.78). Glycemic control was taken from a measure of HbA1c, using the same high-performance liquid chromatographic assay at each site. HbA1c value at first measurement occasion amounted to M = 8.22%, SD = 1.80% in the total sample with 47% having a good (HbA1c < 7.6), 49% a medium (HbA1c 7.6–9.0), and 12% having insufficient glycemic control (HbA1c > 9.1). Diabetic participants and their respective families came from broad socioeconomic strata (53% middle class; 40% of mothers were employed) and family/household structure (83.5% of patients lived in two-parent families, 16.5 % in single-parent or divorced families). The average number of siblings per family was n = 1.39.

Healthy adolescents (n = 119 healthy adolescents) were recruited from secondary schools (79% of the families agreed to participate) and were matched to the diabetes sample with regard to gender, age, parental marital status, marital employment, and socioeconomic status (Luyckx et al., Reference Luyckx, Seiffge-Krenke and Hampson2010). Attrition analysis showed no meaningful differences between participating and drop-out families (Luyckx et al., Reference Luyckx, Seiffge-Krenke, Missotten, Rassart, Casteels and Goethals2013). Healthy participants and their respective families came from broad socioeconomic strata (45% middle class; 60% of mothers were employed) and family/household structure (78.2% of patients lived in two-parent families, 21.8% in single-parent or divorced families). The average number of siblings per family was n = 1.45.

Measures

Self-reported Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms

Psychopathology was assessed by the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach & Edelbrock (Reference Achenbach and Edelbrock1991)). The YSR represents an established instrument with broad use in international research and excellent psychometric properties (Ivanova et al., Reference Ivanova, Achenbach, Rescorla, Dumenci, Almqvist, Bilenberg, Bird, Broberg, Dobrean, Döpfner, Erol, Forns, Hannesdottir, Kanbayashi, Lambert, Leung, Minaei, Mulatu, Novik and Verhulst2007), consisting of 112 self-report items with a three-point Likert response format ranging from 0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, and 2 = often or very often true. The YSR includes a variety of externalizing (e.g., delinquent, aggressive) and internalizing symptoms (e.g., anxious/depressed). In this study the two broad-band scales internalizing, and externalizing symptoms were used. Adolescents completed the German version of the YSR (Doepfner et al., Reference Doepfner, Berner and Leventhal1995) at all three measurement occasions. Cronbach’s alphas across waves ranged from .75 to .84 and .85 to .90, respectively, in the total sample of this study.

Mother’s Report of their Child’s Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms

Mothers rated their children’s level of psychopathology by completing a German translation of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL Doepfner et al. (Reference Doepfner, Berner and Leventhal1995)). The CBCL consists of 112 items, mirroring the internalizing and externalizing items of the YSR from the mothers’ perspective. Norms, reliability, and validity of the German versions of the YSR and CBCL are well-established (Doepfner et al., Reference Doepfner, Berner and Leventhal1995; Lösel et al., Reference Lösel, Bliesener and Köferl1991). Cronbach’s alphas for the total score of mothers’ ratings of their child’s psychopathology symptoms across three waves ranged from .80 to .84 and .86 to .89, respectively, in the current study.

Procedure

In the treatment sample, adolescents (YSR) and their mothers (CBCL) took part in three measurement occasions: beginning of therapy (T1), after the first year (T2), and after the second year (T3) which marked the end of therapy. Both comparison samples (healthy and diabetic samples) were visited annually at home by trained research assistants and were asked to fill out the YSR and CBCL questionnaire. Adolescents and mothers in all groups were requested to complete these questionnaires independently. To guarantee anonymity, all questionnaires were encrypted with a code and placed in a sealed envelope. Data were received, entered, and evaluated by people who were not familiar with the assignment of the codes and the assignment to the three different study groups. Data collection and processing was conducted according to local legal requirements as well as the Declaration of Helsinki in its current form.

Data Analysis

Missing data

Data of all samples stem from two existing longitudinal studies which used multiple imputation (MI) to handle missing data (Luyckx et al., Reference Luyckx, Seiffge-Krenke and Hampson2010; Seiffge-Krenke & Posselt, Reference Seiffge-Krenke and Posselt2021; Seiffge-Krenke, Reference Seiffge-Krenke2001). For the treatment sample (<13% of missing data), fully conditional specification MI was used accounting for age, gender, therapist gender, parental characteristics, and diagnose group (cf. Seiffge-Krenke & Posselt, Reference Seiffge-Krenke and Posselt2021 for further details). For the comparison groups (<11% of missing data) expectation-maximization was used (cf. Luyckx et al., Reference Luyckx, Seiffge-Krenke and Hampson2010).

Methodological procedure

Latent growth curve modeling (GCM) was used to examine inter-individual variability next to intraindividual change over time (Bollen & Curran, Reference Bollen and Curran2006). GCM allows modeling linear and nonlinear time trends while decomposing between- from within-person variance. Moreover, GCM allows flexible group comparisons, rendering this approach particularly suitable for the proposed research questions. The GCMs used in this study consist of four main components: (1) a latent random intercept factor, i.e., the (individual-specific) initial mean level, capturing stable between-person differences (cf. Figure 1 in Online Supplement ESM 1, gray circle labeled “I”). (2) a latent random slope factor, i.e., the (individual-specific) rate of change, capturing within-person change (gray circle labeled “S”). (3) Residual factors, i.e., the error-term, capturing unsystematic variance (arrowheads of manifest indicators). (4) a manifest mean (gray triangle, labeled with “1”), to estimate model-implied means (McArdle, Reference McArdle2009). Model estimation used full-information maximum likelihood (Kline, Reference Kline2011).

Model fitting, parameter, and group testing

The following fit indices were evaluated based on established thresholds (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999; Kline, Reference Kline2011) for good (in brackets: acceptable) model fit: Comparative fit index (CFI) of ≥.97 (≥.90) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of ≤.05 (≤.07). For model specification, we first fitted a linear GCM, i.e., slope factor loadings of 0, 1, and 2 for the respective measurement occasions. To test for nonlinear slope trajectories, we then allowed the second factor loading to be freely estimated (i.e., with a factor loading of 0, λ, 2), using the starting parameters from the linear model. These extended GCM, where some of the base coefficient are estimated freely are also known as latent basis curve models (McArdle, Reference McArdle2009). For model comparison, we followed a cautious procedure (Long, Reference Long2012): A significant decrease of the likelihood ratio test (Δ−2LL with p < .05) and a reduction of ≥4 of the Akaike information criterion (ΔAIC) was necessary to reject the linear model in favor of the better fitting nonlinear model. Parameters of interest (e.g., slope or intercept factor) were tested for significance by constraining these parameters to zero or group equivalence in a nested model and test if constraining the parameter led to a significant deterioration in model fit. For all models, we assumed equal errors over all three measurement occasions. In case of poor model fit, time-specific error was allowed in stepwise manner for one the three measurement occasions (order: 1, 2, 3) and kept in case of significant improvement in model fit. For group comparisons, slope and intercept factors were allowed to vary between groups by adding group as a so-called definition variable with binary (0 = reference group, 1 = comparison group) coding. This means that a group-specific effect for both latent factors (intercept and slope) could be estimated. Significance of group parameters were tested by the same model comparison procedure, with nested models where no differences between groups were assumed. Comparison samples (healthy adolescents and diabetics) were tested separately for RQ1 and RQ3. For the gender-specific analysis (RQ2), comparison groups were combined (N = 228) and grand mean-centered to increase power and stay within common sample size recommendations of N = 200 (Kline, Reference Kline2011).

Effect sizes

Effect sizes for the differences between changes over time were calculated using Cohen’s d for growth curve analysis (Feingold, Reference Feingold2009) by dividing the mean difference over time (i.e., the slope) by the baseline (raw score) standard deviation, multiplied by the study length. For group comparisons, the group effect of the slope factor, which corresponds to the group difference was used.

Testing potential therapist effects, age-specific pathways, and determinants for reporter bias

Therapist effects: While the GCM approach also accounts for the multilevel structure of our data (time points clustered in patients), we did not explicitly assess (potential) therapist effects as an additional level for the treatment sample. To test the robustness of our results and account for potential therapist effects, we re-analyzed our data using linear mixed models with the R package lme4 (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015). Multilevel model specification mirrored the GCM analysis by specifying random effects for slope and intercept. For the comparison model, therapist was added as a random effect. For model comparison, the likelihood ration test was used with a = .05.

Age- (and gender) specific pathways (RQ2): Linear mixed models with random effects for slope and intercept were used to assess if developmental trajectory was influenced by age. For this, the interaction-term between age and time was tested for significance, while controlling for gender. Analyses were performed for treated and nontreated adolescence. The level of significance was p = .05.

Determinants for reporter bias (RQ3): Linear mixed models as described above were used to analyze if the discrepancy (reporter bias) between mother and child changed over time and/or depended on age or gender. To assess a change in reporter bias over time, the differences between the mother’s and child’s perspectives over all three measurement occasions were used as the dependent variable in the multilevel model and tested for a (linear) trend. Secondly, we tested if the adolescents’ developmental trajectory was associated with their mothers’ deviating perspective (i.e., a relative over- or underestimation) of symptoms. A group variable (overestimation yes/no, compared to the adolescent’s perspective) was created and used in interaction with a linear trend. The level of significance was p = .05.

Results

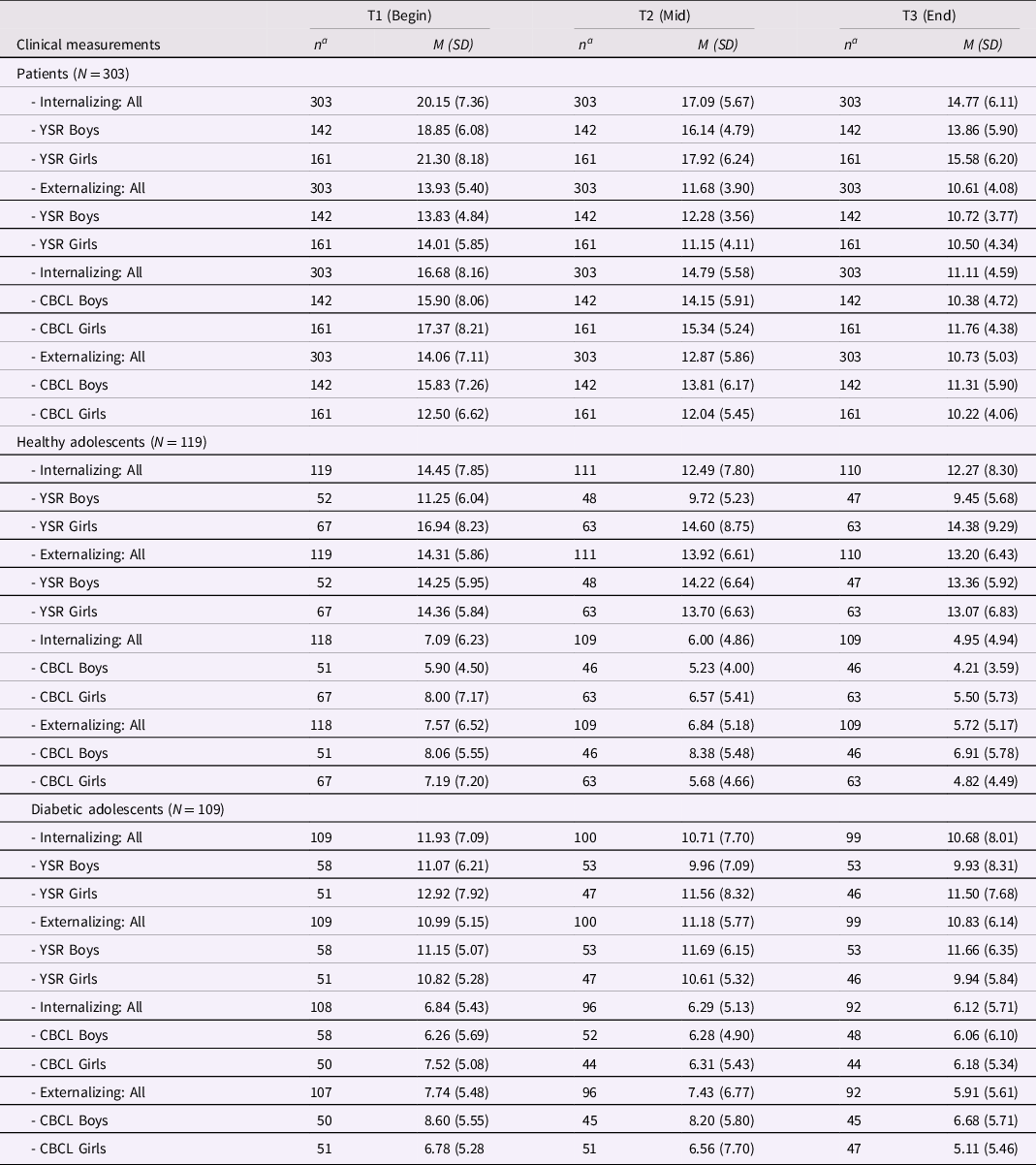

Table 1 shows the descriptive overview of the clinical instruments across all measurement occasions and groups.

Table 1. Overview of levels of psychopathology for participants’ self-report (YSR) and mothers’ report (CBCL)

Note. YSR: German version of the 112-item Youth Self -Report; CBCL: German version of the 112-item Child Behavior Checklist. aNumber of available data points at each measurement occasion of participating group.b Gender refers to the mother’s child gender.

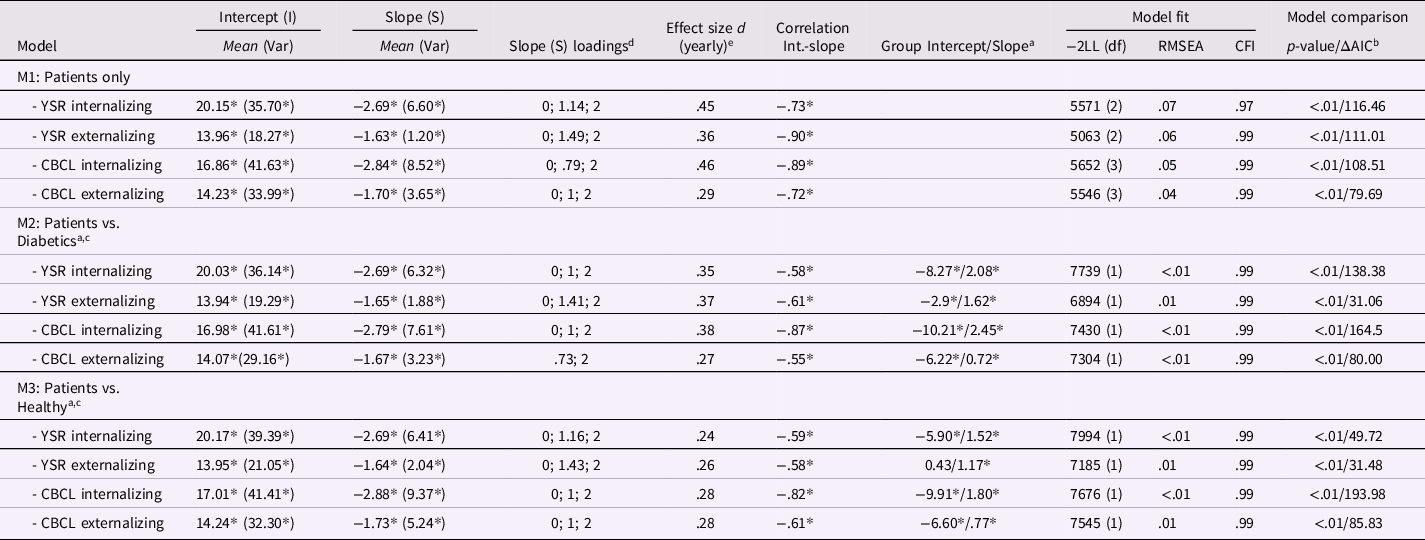

RQ1: Symptom reduction in internalizing (INT) and externalizing (EXT) psychopathology: GCM parameters are reported in Table 2. For treated adolescents (cf. Table 2: upper part) analysis showed a significant decrease over time for YSR and CBCL (both INT and EXT psychopathology), indicated by the deterioration in model fit when slope factors were constrained to zero (cf. column “Model comparison”). Model fit was good or acceptable for all models (cf. Table 2). Slope factor loadings and yearly average effect sizes are reported for all models. The effect size over the complete course of treatment corresponds to the yearly effect multiplied by study length (YSR EXT: d = .90 [.45 * 2]; YSR INT: d = .72 [.36 * 2]; CBCL EXT d = .58 [.29 * 2]; CBCL INT: d = .92 [.46 * 2]). Slope factor loadings indicate if a model with linear (loadings: 0; 1; 2) or nonlinear slope fitted the data better, i.e., improved model fit (Δ−2LL with p ≥ .05; ΔAIC ≤ 4). For nonlinear slopes, yearly effect sizes correspond to the average over all three measurement occasions. Group comparisons with diabetics (cf. Table 2: M2) and healthy adolescents (M3) showed significant group differences in both slope and intercept. Corresponding group differences in change over time between treated and diabetic adolescents (M2) and treated and healthy adolescents (M3) were between d = .27–.37. Note that these effect sizes indicate the additional reduction in the treatment sample when the developmental progression of the diabetic (YSR INT/EXT: d = .09/.02; CBCL INT/EXT: d = .07/.20) and healthy (YSR INT/EXT: d = .17/.11; CBCL INT/EXT: d = .19/.21) samples are accounted for. Information about clinically significant change (CSC) are provided in Online Supplement ESM 6.

Table 2. Growth curve modeling (GCM) estimates and fit indices with model comparisons for the treatment group (upper part: treated adolescents) and the comparison groups (diabetics and health adolescents)

Note. YSR: German version of the 112-item Youth Self-Report; CBCL: German version of the 112-item Child Behavior Checklist. *p < .05. aReference group are patients compared to diabetics (M2) and healthy adolescents (M3). bComparison with model where slope is constrained to zero, thus assuming change over time. cModel comparison with model where grouped slope and intercept factors are constrained to zero, thus assuming no differences between groups. dNonlinear factor loadings (0, λ, 2) are shown when freely estimating λ led to a significant improvement in model fit. eEffect sizes for patients refer to the (yearly) symptom reduction; For group comparisons (M2 and M3), effect sizes represent group differences of the (yearly) effect size.

RQ2: Gendered pathways in symptom severity and change in internalizing (INT) and externalizing (EXT) symptoms: For treated adolescents, Figure 1 (cf. Online Supplement ESM 1) shows the most important GCM parameters, i.e., the group effects for slope and intercept with the difference (Δ) for girls. All models showed good model fit (RMSEA ≤ .01; CFI ≥ .98; cf. Table 2 Online Supplement ESM 2). Regarding internalizing symptoms (YSR and CBCL), girls showed a higher initial symptom severity (YSR: ΔI = 2.37; p < .01; ΔAIC = 7.53; CBCL: ΔI = 1.33; p = .02; ΔAIC = 4.16) compared to boys. For externalizing symptoms, YSR showed no gender-specificity (p = .10; ΔAIC = .70) while CBCL showed lower initial symptom severity and a lower symptom reduction (ΔI = −3.18; ΔS = 1.09; p < .01; ΔAIC = 13.04) for girls, corresponding to a (yearly) group difference of d = .19. Regarding age-specific pathways in the patient group, linear mixed model analyses showed no significant interaction between time and age for YSR (p = .14– .48) and CBCL INT (p = .49). However, for CBCL EXT, younger adolescents exhibited a steeper decline in symptomatology throughout therapy (p = .03; cf. Online Supplement ESM 3). For the (combined) comparison group of diabetic and healthy adolescents, a similar pattern emerged: For internalizing symptoms (YSR), girls reported higher intercepts (ΔI = 3.90; p = .01; ΔAIC = 4.47). The same trend was found for CBCL (ΔI = 1.71; p = .03; ΔAIC = 2.96), but the model comparison did not reach the cutoff of ΔAIC = 4. No gender-specificity was found for self-reported externalizing symptoms (YSR: p = .40; ΔAIC = 1.96) while from the perspective of their mothers (CBCL) girls showed a lower initial symptom severity (ΔI = 1.91; p < .01; ΔAIC = 4.88), but no differences in symptom reduction (ΔS = −.13; p = .68; ΔAIC = 1.83). Regarding age-specific pathways in the comparison groups, analyses showed no significant interaction between trajectory and age (p = .19–.87; cf. ESM 3).

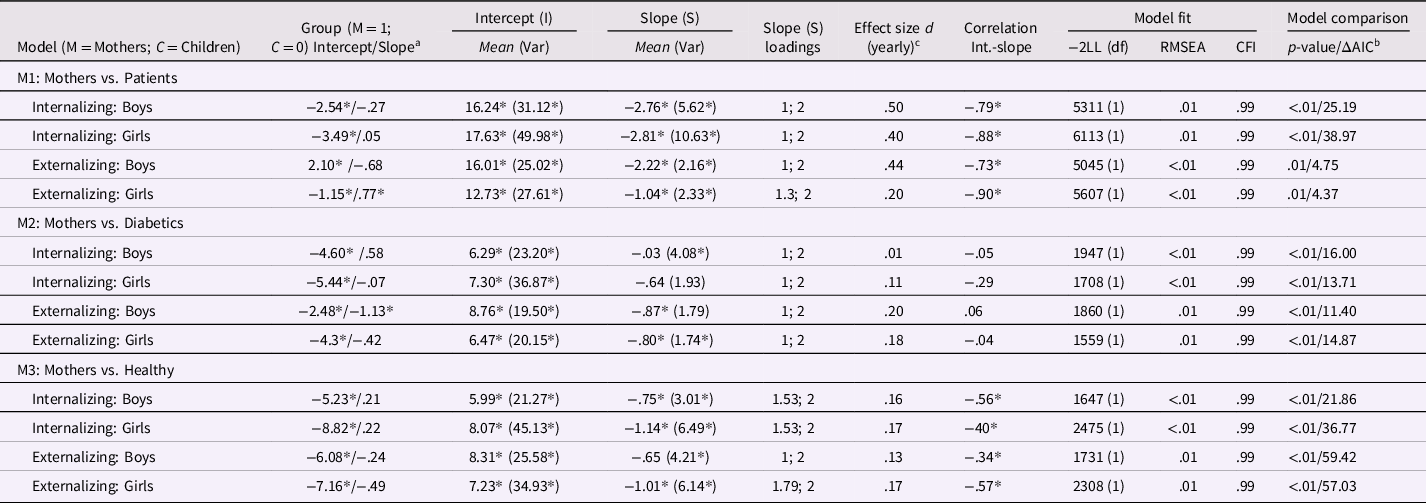

RQ3: Differences in mother’s perception of their children in internalizing (INT) and externalizing (EXT) psychopathology and dependence on the child’s gender: GCM parameters are shown (separately for boys and girls) in Table 3 for mothers and patients (M1), diabetics (M2), and healthy adolescents (M3). Over all three groups, for internalizing symptoms, mothers underestimated their child’s symptom severity (cf. Table 3: CBCL: ΔI = 2.54–8.82;), but not the within-person change, regardless of the adolescents’ gender. For healthy and diabetic adolescents, this pattern was also found for externalizing symptoms (ΔI = 2.48–7.16). For treated patients, a gender-specific pattern emerged, with mothers significantly overestimated symptom severity for their sons (ΔI = 2.10) while underestimating symptom severity (ΔI = −1.15) and overestimating symptom reduction (ΔS = .77; d = .15) of their daughters. Further analyses of these differences showed that a higher discrepancy (INT and EXT) was related to higher age in adolescents across all three groups (p < .04). Moreover, the extent of discrepancy increased over time in treated adolescents regarding internalizing (p = .02) but not externalizing (p = .75) symptoms, even when age and gender were controlled as covariates. In the two comparison groups, reporter bias did not change over time (p = .08–.51: cf. Online Supplement ESM 4). Lastly, we tested if adolescents developed differently over time depending on their mother’s deviating perspective (i.e., relative over- or underestimation) of their symptoms: There were no differences in developmental progression in the two control groups (p = .31 – .86). For treated adolescents, mothers who underestimated externalizing symptoms of their child reported a slower decline during therapy (p = .02), which indicates that mothers might adjust their perception over time and thus might perceive the therapeutic progress to be less pronounced.

Table 3. Growth curve modeling (GCM) estimates and fit indices with model comparisons for the treatment group (upper part: treated adolescents) and the comparison groups (diabetics and health adolescents)

Note. YSR: German version of the 112-item Youth Self-Report; CBCL: German version of the 112-item Child Behavior Checklist. *p < .05. aReference group are treated patients (M1), diabetics (M2), and healthy adolescents (M3), i.e., values represent differences to their mothers' perspective. bModel comparison with models where grouped slope and intercept factors are constrained to zero, thus assuming no differences between groups. cEffect sizes refer to the average (yearly) symptom reduction over time of the group (patients, healthy adolescents, and adolescents with juvenile diabetes) as reported by mothers and their children.

Therapist effects: Adding therapists as cluster variable did not improve model fit for internalizing (YSR: p = .28; intra-class correlation [ICC] = .02; CBCL: p = .61; ICC = .01) or externalizing symptoms (YSR: p = .61; ICC = .01; CBCL: p = .91; ICC < .01). Parameters for slope and/or intercept in the multilevel analyses were largely identical compared to the GCM analyses, regardless of including therapist as random effect into our models or not (for the complete results of the multilevel analyses see: Online Supplement ESM 3 and ESM 5).

Discussion

This study addresses the given sparsity of studies in a naturalistic setting and the limitations in existing studies, specifically, when it comes to adolescent patients in long-term psychodynamic treatment (Midgley et al., Reference Midgley, Mortimer, Cirasola, Batra and Kennedy2021). Based on concepts of developmental psychopathology (Masten, Reference Masten2006), the question of whether psychodynamic psychotherapy works (Liu & Adrian, Reference Liu and Adrian2019) was assessed in comparison to the normal developmental progression of healthy and diabetic adolescents that traverse the period from early to mid-adolescence. By controlling for stable between-person differences, we captured and examined actual within-person change of patients undergoing psychodynamic treatment with two comparison groups without psychotherapy. In all samples, a broad spectrum of clinically relevant symptoms was assessed from the adolescents’ and their mothers’ points of view. The results did not change when tested for robustness with linear mixed models by explicitly considering therapists as an additional cluster variable.

Effectiveness of psychodynamic treatment: within-person change over time

Clinically significant symptoms, if untreated during adolescence, lead to severe psychopathology in the following years (Ivanova et al., Reference Ivanova, Achenbach, Rescorla, Turner, Ahmeti-Pronaj, Au, Maese, Bellina, Caldas, Chen, Csemy, da Rocha, Decoster, Dobrean, Ezpeleta, Fontaine, Funabiki, Guðmundsson, Harder, de la Cabada, Leung, Liu, Mahr, Malykh, Maras, Markovic, Ndetei, Oh, Petot, Riad, Sakarya, Samaniego, Sebre, Shahini, Silvares, Simulioniene, Sokoli, Talcott, Vazquez and Zasepa2015). Hofstra et al. (Reference Hofstra, van der Ende and Verhulst2001) found that a substantial proportion of adolescents with high symptomatology are more likely to meet the criteria for DSM-IV diagnosis in adulthood. Whether psychodynamic treatments effectively reduce adolescent patients’ internalizing and externalizing symptomatology, compared to normative developmental progression observed in two comparison samples, is therefore a research question of great clinical relevance, not only because of the suffering of those left untreated but also because of the enormous economic costs for treatment and the even higher economic burden of untreated psychopathology for future health care systems.

Our results showed that adolescent patients carried a clinically significant symptom burden at baseline compared to the two comparison groups, regardless of the assessed perspective (mother or child). The patients’ psychopathology mean level was in the clinical range, which was a clear indication for psychotherapy, whereas the psychopathology scores of healthy adolescents and adolescents with diabetes were in the normative range and matched the levels of nonclinical adolescents in many Western industrialized countries (Rescorla et al., Reference Rescorla, Ivanova, Achenbach, Begovac, Chahed, Drugli, Emerich, Fung, Haider, Hansson, Hewitt, Jaimes, Larsson, Maggiolini, Marković, Mitrović, Moreira, Oliveira, Olsson and Zhang2012). Of note, the clinical spectrum of diagnosis, treatment principles, and the duration of treatment in our clinical sample was representative of outpatient care in this age group in Germany (Maur & Lehndorfer, Reference Maur and Lehndorfer2017).

Throughout the 2-year psychodynamic treatment, adolescent patients showed a yearly (in brackets: over the complete course of treatment) significant symptom decrease with medium to large effects in internalizing symptoms of d = .45 (.90) and externalizing symptoms of d = .36 (.72), based on their self-report. From their mother´s perspective, symptom severity also decreased significantly with comparable effect sizes of d = .46 (.92) for internalizing, and d = .29 (.58) for externalizing symptoms. Thus, the psychodynamic treatment effectively led to a reduction of a broad spectrum of clinically relevant symptoms in adolescents, both from the patient’s and their caregiver’s perspectives. Moreover, the nonlinear slope of internalizing and externalizing symptoms over time suggests that patient’s self-perceived burden of symptoms already decreased significantly during the first year of treatment while slower but still significant decreases were substantiated toward the end of therapy (after 2 years). Mothers tend to notice the decreasing symptom burden more steadily (for externalizing symptoms) or even with a delay in the second half of 2-year treatment (internalizing symptoms). Notably, patients in our study reported internalizing and externalizing scores in a higher clinical range before treatment and stronger decreases during treatment than those in the study by Krischer et al. (Reference Krischer, Smolka, Voigt, Lehmkuhl, Flechtner, Franke, Hellmich and Trautmann-Voigt2020). Our findings blend into the literature indicating that long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy can significantly reduce the symptomatology of adolescents with different psychiatric problems (Cropp et al., Reference Cropp, Taubner, Salzer and Streeck-Fischer2019; Midgley et al., Reference Midgley, O’Keeffe, French and Kennedy2017; Salzer et al., Reference Salzer, Cropp, Jaeger, Masuhr and Streeck-Fischer2014; Seiffge-Krenke, Reference Seiffge-Krenke2020a).

Our study examined a typical sample of adolescents in need of psychotherapy, with higher scores of internalizing disorders such as ICD-10 F32 (depression) and F40 (phobic anxiety), compared to externalizing disorders such as F93 (emotional disorders with onset specific to childhood) (Maur & Lehndorfer, Reference Maur and Lehndorfer2017). Externalizing disorders are a common reason for referral to child mental health services (Sadler et al., Reference Sadler, Vizard, Ford, Marchesell, Pearce, Mandalia, Davis, Brodie, Forbes and Goodman2018), but have rarely been examined concerning the effectiveness of psychodynamic psychotherapy (Midgley et al., Reference Midgley, Mortimer, Cirasola, Batra and Kennedy2021). Our findings are promising, not only for the long-term treatment of internalizing symptoms, confirming previous findings (Midgley et al., Reference Midgley, O’Keeffe, French and Kennedy2017; Weitkamp et al., Reference Weitkamp, Daniels, Hofmann, Timmermann, Romer and Wiegand-Grefe2014, Reference Weitkamp, Daniels, Baumeister-Duru, Wulf, Romer and Wiegand-Grefe2018) but also for the psychodynamic treatment of externalizing disorders that have received less research attention.

The effect sizes in our study are larger than in the meta-analysis by Weisz et al. (Reference Weisz, Kuppens, Ng, Eckshtain, Ugueto, Vaughn-Coaxum, Jensen-Doss, Hawley, Krumholz Marchette and Chu2017) which reported an overall effect size of d = .45 for psychodynamic treatments compared to a control condition. Of note, our effect size refers to the actual within-person change throughout treatment and in comparison to two relevant control groups (Feingold, Reference Feingold2009). Notably, since the previous meta-analysis mostly examined shorter psychodynamic treatments, our results show that long-term psychodynamic therapy (of about 86 weekly sessions) yields an additional treatment effect for both internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Our results are comparable to evidence from long-term psychodynamic therapy from adult patients, that showed an overall effect of d = .44 – .68 (Leichsenring & Rabung, Reference Leichsenring and Rabung2008) with sustainable effects in follow-ups.

Effectiveness of psychodynamic treatment: within-person change compared to the normative developmental progression of nontreated adolescents

Several studies demonstrated that externalizing and internalizing symptoms, when untreated, follow different developmental trajectories. Internalizing behavior problems tend to increase with the onset of puberty and the transition into adolescence and seemed to be stable thereafter (Costello et al., Reference Costello, Copeland and Angold2011). The 10-year-longitudinal studies by Van der Valk et al. (Reference van der Valk, Spruijt, Goede, Maas and Meeus2005) on a normative sample indicate that internalizing behavior of adolescents increases with age, with a rather steep increase in late adolescence and young adulthood. Externalizing behavior problems increase again during adolescence but decrease in young adulthood (Steinberg, Reference Steinberg2007).

Our study on early adolescents who traverse into mid-adolescence showed that patients displayed a significant decrease in both internalizing and externalizing symptoms, even when the developmental progression of the nontreated control groups was accounted for. In other words, adolescents who underwent psychodynamic treatment reported a higher yearly (in brackets: over the complete course of treatment) decrease in symptom severity compared to both control groups, with medium effect sizes of d = .24–.35 (.48–.70) for internalizing and d = .26–.37 (.52–.74) for externalizing symptoms. This was also true from the mother’s perspective with d = .28–.38 (.52–.76) for internalizing and d = .27–.28 (.54–.56) for externalizing symptoms. Notably, the two comparison groups showed low decreasing trajectories in internalizing and stable low trajectories in externalizing symptoms over time (d = .02–.21). The fact that symptomatology has decreased significantly is noteworthy for healthy young people, but is particularly striking in youths with diabetes, who are under considerable additional stress in managing their metabolic control under hormonal turbulences, which has often led to an increase in psychopathology (Lustman et al., Reference Lustman, Anderson, Freedland, Groot, Carney and Clouse2000). This suggests improvement also for those not in treatment for (the assessed) 2 years, potentially related to neuronal development and reorganization, which might have resulted in increased coping capacity (Seiffge-Krenke et al., Reference Seiffge-Krenke, Aunola and Nurmi2009) and improvements in self-regulation (Bauchaine & Cicchetti, Reference Bauchaine and Cicchetti2019). In this context, it should be noted that the patients in later phases of the therapy worked on the deepening and integration of experiences made in the first year of treatment, which resulted in a further significant decrease in psychopathology, compared to the two control groups. Together, these findings add further evidence to adolescence as a key period of growth. While the long-term psychodynamic treatment clarifies problems and promotes the patients’ competence, adolescents from the nontreatment group also develop competence over 2 years to shift the development in a positive way (Luthar & Cicchetti, Reference Luthar and Cicchetti2000; Wekerle et al., Reference Wekerle, Waechter, Leung and Leonard2007). Overall, this points to the substantial agency of young people in managing age-specific tasks, even under difficult conditions (Seiffge-Krenke et al., Reference Seiffge-Krenke, Kiuru and Nurmi2010).

Gender- and age-specific pathways in symptom severity and within-person trajectories

Additionally, our study investigated gender differences in the mean levels at the outset and analyzed whether males and females follow similar developmental trajectories both in the treatment and the nontreatment groups over time. In epidemiological research across countries (Rescorla et al., Reference Rescorla, Achenbach, Ivanova, Dumenci, Almqvist, Bilenberg, Bird, Broberg, Dobrean, Döpfner, Erol, Forns, Hannesdottir, Kanbayashi, Lambert, Leung, Minaei, Mulatu, Novik and Verhulst2007), females obtained significantly higher scores than males, most consistently for anxious/depressed in 21 countries and over all internalizing disorders in 17 countries. Further, males scored consistently higher than females in externalizing disorders, most consistently in conduct problems (17 countries). In our study, girls reported significantly higher internalizing values at baseline compared to boys, but no differences in trajectories. This was true for adolescent patients, and both comparison groups, confirming findings on clinical groups of adolescents (Krischer et al., Reference Krischer, Smolka, Voigt, Lehmkuhl, Flechtner, Franke, Hellmich and Trautmann-Voigt2020), on normative samples (Polanczyk et al., Reference Polanczyk, Salum, Sugaya, Caye and Rohde2015; Rescorla et al., Reference Rescorla, Achenbach, Ivanova, Dumenci, Almqvist, Bilenberg, Bird, Broberg, Dobrean, Döpfner, Erol, Forns, Hannesdottir, Kanbayashi, Lambert, Leung, Minaei, Mulatu, Novik and Verhulst2007), and on adolescents with diabetes (Kanner et al., Reference Kanner, Hamrin and Grey2003). It is, therefore, a robust finding. Moreover, our results did not change based on the adolescents’ age. For externalizing symptoms, we found no gender-specific differences between girls and boys in their self-report, neither in severity nor development, but found that mothers reported a significantly lower severity and decline for girls. Additionally, assessing age-specificity showed that younger treated adolescents had a steeper decline in externalizing symptoms from their mothers’ point of view (but not in their self-report). This was not true for the two control samples, indicating that mothers’ perception of the trajectory of externalizing symptoms might depend on whether their child is in psychodynamic therapy. Thus, our results showed that developmental trajectories are relatively robust across ages within the range of 12–18 years. At the same time, our results further substantiated known gender specificities, especially for mean level differences of internalizing symptoms.

Earlier theoretical models used the gender intensification hypotheses for explaining the emergence of gender differences in psychopathology (Hill & Lynch, Reference Hill, Lynch and Brooks-Gunn1983). In recent years, traditional gender roles vary (Crouter et al., Reference Crouter, Whiteman, McHale and Osgood2007), and early maturation seemed to have an equal impact on both genders (Ullsperger & Nikolas, Reference Ullsperger and Nikolas2017). An increase in externalizing symptoms in girls and internalizing symptoms such as depression and eating disorders in boys (Strother et al., Reference Strother, Lemberg, Stanford and Turberville2012) and a narrowing down of gender differences in depression (Costello et al., Reference Costello, Erkanli and Angold2006) seem to support this change. In our study, the rapprochement between girls and boys, in terms of the level and course of externalization, is a uniform result in all three groups, confirming previous findings of Priess et al. (Reference Priess, Lindberg and Hyde2009).

Differences between reporter’s perspectives

There is a strong consensus that the clinical assessment of adolescents’ psychopathology requires data from multiple informants (Salbach-Andrae et al., Reference Salbach-Andrae, Klinkowski, Lenz and Lehmkuhl2009). Already an early meta-analysis by Achenbach et al. (Reference Achenbach, McConaughy and Howell1987) showed low parent–adolescent agreement with a mean correlation of r = .22 between parents and adolescents. These results have been replicated (Berg-Nielsen et al., Reference Berg-Nielsen, Vika and Dahl2003; Ferdinand et al., Reference Ferdinand, van der Ende and Verhulst2004; Rescorla et al., Reference Rescorla, Ginzburg, Achenbach, Ivanova, Almqvist, Begovac, Bilenberg, Bird, Chahed, Dobrean, Döpfner, Erol, Hannesdottir, Kanbayashi, Lambert, Leung, Minaei, Novik, Oh and Verhulst2013) with quite different results in clinical and nonclinical samples. In studies of nonclinical samples, adolescents reported higher severity ratings than their parents (Achenbach et al., Reference Achenbach, McConaughy and Howell1987; Seiffge-Krenke & Kollmar, Reference Seiffge-Krenke and Kollmar1998; Vierhaus & Lohaus, Reference Vierhaus and Lohaus2008). Some studies involving clinically referred samples document a reverse discrepancy (Kazdin et al., Reference Kazdin, French and Unis1983; Phares & Danforth, Reference Phares and Danforth1994; Salbach-Andrae et al., Reference Salbach-Andrae, Klinkowski, Lenz and Lehmkuhl2009), but other studies show that parents of patients in treatment reported quite low levels, compared to their child’s report (Krischer et al., Reference Krischer, Smolka, Voigt, Lehmkuhl, Flechtner, Franke, Hellmich and Trautmann-Voigt2020).

In our study, the mean correlation of the agreement between mothers and children was in the expected range (INT with r = .35; EXT with r = .30), and mothers, too, consistently reported lower levels of internalizing symptoms in their children, regardless of the child’s gender. This was also true for externalizing symptoms with an exception for treated adolescents: For this group, our results suggested a gender-specific bias, where mothers reported higher externalizing symptoms than their sons but lower scores than their daughters. Over all three groups, the extent of the reporter bias was higher for older adolescents across both externalizing and internalizing symptoms, suggesting increasing autonomy from parents with decreasing self-disclosure of the child with growing age (Smetana, Reference Smetana2010). For the treated adolescents, our results further showed that the discrepancy between mother and child grew over time for internalizing symptoms, regardless of the child’s gender. This was not the case in the comparison groups or for externalizing symptoms. Thus, our results suggest a pattern of reporter bias that differs between treated and nontreated adolescents. From a clinical perspective, this implies two implications: First, therapists should consider the potential gender bias for externalizing symptoms (i.e., mothers report higher levels for sons and lower levels for daughters) and take this into account during the therapeutic process. Second, the therapist should pay attention to potentially higher discrepancy for older adolescents. For example, German health insurance allows and pays for 1 hour of parental work after every 4th therapy session with the patient. While this is intensively used in child patients, it is less often used in adolescent patients, which might contribute to these discrepancies. As mother–adolescent disagreement may have important clinical significance (Ferdinand et al., Reference Ferdinand, van der Ende and Verhulst2004), we also tested if patients’ trajectories differ based on whether mothers report higher or lower levels compared to their children. We found that mothers who reported lower externalizing symptoms than their children also reported slower decline during therapy (p = .02), i.e., perceived the therapeutic progress to be less pronounced. This was not the case for the two control groups, further substantiating patient-specific differences in reporter bias.

From a broader perspective, our results indicate that mothers tend to report less symptom severity generalized across adolescents with different health status and across different symptom groups. Our results further indicate that with nontreated adolescents this bias is not limited to internalizing symptoms which are known to be more difficult to notice (Vierhaus & Lohaus, Reference Vierhaus and Lohaus2008), but also applies for externalizing symptoms. Research confirmed parental monitoring as a protective factor against delinquency, juvenile offending, and antisocial behavior, and revealed similar links with other indices of problem behavior such as depression (Dishion & McMahon, Reference Dishion and McMahon1998; Racz & McMahon, Reference Racz and McMahon2011). In this context, adolescent disclosure to parents seems to be important (Keijsers et al., Reference Keijsers, Branje, Frijns, Finkenauer and Meeus2010), e.g., the extent to which adolescents tell their parents about their leisure time activities, friendships, whereabouts, and inner feelings. Monitoring (and adolescent self-disclosure) seems to be necessary for externalizing problem behavior and is also important for parents of diabetic adolescents regarding the adolescents’ diabetes management (Berg et al., Reference Berg, King, Butler, Pham, Palmer and Wiebe2011).

Clinical significance of the study, limitations, and suggestions for further research

In our study, psychodynamic treatment for adolescents significantly reduced severity of both internalizing and externalizing symptoms throughout treatment. Patients exhibited a significant reduction, even when we controlled for the developmental progression in two meaningful comparison samples. Hence, our study adds to the increasing evidence of the effectiveness of long-term psychodynamic therapy in treating a wide range of mental health difficulties in children and adolescents (Goodyer et al., Reference Goodyer, Tsancheva, Byford, Dubicka, Hill, Kelvin, Reynolds, Roberts, Senior, Suckling, Wilkinson, Target and Fonagy2011; Midgley et al., Reference Midgley, Mortimer, Cirasola, Batra and Kennedy2021). It is yet unclear which factors were associated with a good outcome, including patient factors (such as diagnosis or treatment motivation), therapist factors (such as competence or adherence), or factors of the therapeutic process (such as therapeutic relationships or duration). Although therapists in our study were highly trained and closely supervised, there was no formal assessment of adherence to the treatment model, which was a limitation. Future studies could profit from using more formal procedures to assess treatment adherence, for example, the APQ (Calderon et al., Reference Calderon, Schneider, Target and Midgley2017) to establish that the interventions were delivered as planned (Leichsenring et al., Reference Leichsenring, Salzer, Hilsenroth, Leibing, Leweke and Rabung2011) and to evaluate which of these factors may account for the change, which also includes a further assessment of differences between therapists both with regard to their work with patients and parents. Since we included two reporters (mothers and adolescents), we found that a substantial part of the adolescents’ burden remains hidden from their mothers. As fathers make their own contribution to the assessment of psychopathology of their children (Cassano et al., Reference Cassano, Adrian, Veits and Zeman2006), taking both parental perspectives into account might further shed light on the discrepancies in the perceived burden and the progress their children accomplish over time. By applying GCM, we captured within-person change by accounting for stable between-person differences. Our sample size is within the (debated) range of sample size recommendation of about N = 200 (Kline, Reference Kline2011). Yet, especially for the group comparison, models became less robust, indicated by the poor model fit for the initial models, which we addressed by allowing nonlinear slopes and allowing time-specific error and using linear mixed models. Nevertheless, our sample size might have limited statistical power of our study. Moreover, given the number of measurement occasions, we were limited in testing for more complex slopes or moderators.

Our study included two relevant comparison groups and thus addresses recommendations for naturalistic (effectiveness) studies in which randomization often is not feasible and/or more difficult than in controlled (efficacy) studies (Midgley et al., Reference Midgley, O’Keeffe, French and Kennedy2017; Midgley & Kennedy, Reference Midgley and Kennedy2011). By accounting for the developmental progression of the two untreated control groups, we were more clearly able to distinguish between developmental change and the effect of psychotherapy. Building on this, future studies might also add intermittent factors which might impact both baseline symptomatology and change over time, such as severe stressors like critical life events (Compas & Phares, Reference Compas and Phares1991), coping abilities (Seiffge-Krenke, Reference Seiffge-Krenke2004), or change in social relationships (Steinberg, Reference Steinberg2014). Not only is more appreciation for and research analyzing the competencies of healthy adolescents and adolescents with diabetes necessary, but more research is also needed to analyze growth and change in further subgroups at risk for example early maturing adolescents, and to evaluate how the quality of parent–adolescent relationship and supportive peer relations may have contributed to a positive outcome in the comparison groups (see, e.g., Chae et al., (Reference Chae, East, Delva, Lozoff and Gahagan2020)).

To conclude, this critical developmental period presents psychotherapists and parents with an opportunity to intervene and guide the development of youth. Health professional may profit from integration of clinical and developmental perspectives, thus not only focusing on deficits but also directing their attention to growth and change with a substantial agency in young people.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579422001341

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the participating families, who allowed us to gain insights into personal and often difficult aspects of their lives during a long period of time. Moreover, we wish to thank the participating therapists for exposing their work to a scientific assessment, which is not seldomly a fearful and difficult task.

Funding statement

Parts of this work were supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [DFG] under grant number 408-11 and BMFT under grant number 0706567given to the first author.

Conflicts of interest

None.