Policy Significance Statement

Establishing routine data sharing presents legal, technical, and cultural challenges, particularly in large health and human service agencies. Through a collaborative, participatory approach, the NCDHHS successfully established enterprise-wide data governance and a legal framework for routine data sharing to support data-driven policymaking and, ultimately, improve health outcomes for residents. This research presents a successful, actionable, and replicable framework for developing and implementing processes to support intradepartmental data access, integration, and ethical use.

1. Introduction

Public agencies hold important, yet largely unused, administrative data on the individuals, families, and communities they serve. These data are routinely collected in the course of service delivery and, taken together, form a rich picture of people’s experiences and trajectories. One major challenge is that each agency, department, or program typically has access to only one piece of this larger picture. When these compartmentalized datasets are shared and integrated, they can be used to enhance service delivery, inform policymaking, and reduce costs. For instance, linking data across child welfare, juvenile justice, and public assistance in Los Angeles County showed that youth exiting foster care have the greatest risk of accessing public assistance within the first 18 months after discharge—an important finding to support California’s extended foster care legislation (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Stephen, Kim, Culhane, Moreno, Toros and Stevens2014; Culhane et al., Reference Culhane, Byrne, Metraux, Moreno, Toros and Stevens2011). However, if individuals and families cannot be connected across siloed data systems, there is limited ability to measure impact, understand the interplay of various inputs and interventions, and improve results to support well-being and health equity (North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, 2021).

This type of person-centered data organization presents legal, technical, and cultural challenges, especially across agencies (Putnam-Hornstein et al., Reference Putnam-Hornstein, Ghaly and Wilkening2020). At the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS), we have been grappling with this challenge in light of our vision to “buy health for North Carolinians” (Wortman et al., Reference Wortman, Tilson and Cohen2020) through data-driven policymaking. Below, we present a case study of NCDHHS’s successful efforts to establish a departmental data strategy with a focus on intradepartmental data governance and legal framework for routine data sharing, all working toward the goal of data-driven policymaking and, ultimately, improved outcomes for residents. These actions served to enhance data sharing in two complementary ways: cultural and tactical. The very creation and existence of the Data Office, with senior leadership and executive support, created a culture of data use to complement the culture of caution and privacy protection. In addition, the innovative governance and legal framework improved the efficiency of data sharing processes and protocols in this new, increasingly data-driven environment.

1.1. Developing data strategy and shifting culture

When we began this work in 2019, data sharing and integration did occur across NCDHHS, but it proved more of an endurance test for staff than a standardized process. We were spending thousands of hours per year working on data flow, and we knew that to achieve our vision, we needed a clear strategy for making responsible data sharing a routine part of organizational culture. Shifting strategy and culture for a large, complex institution—$26B budget, 33 Divisions and Offices, over 17,000 employees, serving the 9th most populated state, situated in a dynamic political context—does not happen by policy or directive alone. Rather, it is a process built upon shared vision and guiding principles that shape “how we do things.” Furthermore, to make data-informed policymaking routine, we recognized the need to include stakeholders from across the department to co-create new processes that would result in a culture of data use that is legal, ethical, and a good idea (Hawn Nelson et al., Reference Hawn Nelson, Kemp, Jenkins, Rios Benitez, Berkowitz, Burnett, Smith, Zanti and Culhane2022; Hawn Nelson and Zanti, Reference Hawn Nelson and Zanti2023).

We relied on participatory methods to develop a data governance process and legal framework that has been implemented across NCDHHS and operationalized through the creation of the NCDHHS Data Sharing Guidebook (North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, 2023b). The newly implemented legal framework clarifies requirements and guidelines, provides approved language and templates for agreements while ensuring ethical use and mitigating legal risk, and has shown nearly 90% savings for staff effort and time to completion for some intradepartmental data sharing; allowing data to be more readily acted upon to better serve North Carolinians, improving services, and reducing costs (Hawn Nelson, Reference Hawn Nelson2022).

The work of building strong data strategy and culture has been led by the Chief Data Officer (CDO) and the Data Office, created in 2019 to provide leadership and support for data-driven decisions across NCDHHS. The CDO was tasked with “managing data as a strategic asset and putting it to its highest and best use.” (Kleykamp, Reference Kleykamp2020, p. 1) At the same time, Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy (AISP), an initiative of the University of Pennsylvania (Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy, 2024), was engaged to support data governance initiatives and incorporate data governance into the daily operations of the NCDHHS Data Office. AISP functioned as a member of the team working under the CDO. One of the CDO’s first tasks was creating the NCDHHS Data Strategy Framework shown in Figure 1. While this research focuses on the work around the data governance pillar, all pillars are interrelated and essential to NCDHHS’ data-driven mission.

Figure 1. Five pillars of NCDHHS data strategy framework.

Source: Reproduced with permission from the NCDHHS Data Office.

This strategic work is iterative and builds upon decades of strong data practices at NCDHHS in using data for daily operations and providing access to researchers, when permissible and aligned with department goals. Coordinating department-wide data governance started with a commitment from executive leadership to appropriately staff and resource data governance as a core task of the Data Office, knowing the work would be long term and require an organizational “home” with highly skilled staff. It is also important to note, while inevitable staffing changes did occur, core staffing has remained constant, even amid the great resignation (Parker and Menasce Horowitz, Reference Parker and Menasce Horowitz2022). Specifically, the CDO, AISP subject matter expert, lead from the Office of General Counsel, and many other supporting roles have remained constant, enabling a strong and trusting partnership. Of note, all authors have been engaged in this work together since 2019. The importance of these fundamental components to lead data governance work at the enterprise level—the support of executive leadership; sufficient resources; and consistent, highly skilled staff—cannot be overstated.

2. Methods and data

2.1. Participatory action research (PAR)

PAR was the primary approach we used to build a governance and legal framework for routine data sharing in the NCDHHS. PAR is a methodological investigation where parties engage around collaborative problem-solving and goal attainment through systematic investigation and concrete action to advance general knowledge in a field. The six building blocks for a PAR project include building relationships; establishing working practices; establishing a common understanding of the issue; observing, gathering, and generating materials; collaborative analysis; and planning and taking action (Cornish et al., Reference Cornish, Breton, Moreno-Tabarez, Delgado, Rua, de-Graft Aikins and Hodgetts2023). Relationship building was prioritized from the outset of this work. The process of conducting the Data Landscape Overview described in the following section allowed for data collection and relationship building. In alignment with PAR values, we included a range of NCDHHS participants with varying levels of expertise and power and committed to consensus-based review and editing, with no one person “owning” analysis or determining final versions of co-created process documents (Baum et al., Reference Baum, MacDougall and Smith2006). As part of this process, clear working practices were established around transparency and authentic feedback mechanisms. For every document or resource created, staff receive draft copies of all findings and products and have an opportunity to provide input before published. This has worked to establish a culture of authentic partnership and trust between the research team and NCDHHS staff.

A distinguishing feature of PAR is that it rejects academic researchers as expert and centers participants—in this case, NCDHHS staff—as expert. Therefore, to establish common understanding of the issue at hand, we started with on-the-ground NCDHHS staff to define the topic of inquiry—How can we best support strategic data use across NCDHHS to leverage data assets? We then pursued this question through the Data Landscape Overview which led us to refine the initial question based on participant input—How can we make data sharing across the department less painful and more routine without unnecessary data use agreements (DUAs)? The Data Landscape Overview allowed us to observe, gather, and generate the materials needed to address this core question, the methods for which are described below in further detail. In addition, conducting the Data Landscape Overview was an iterative process that included collaborative reflection and analysis, which culminated in four key actions described in the Results.

2.2. Data landscape overview

AISP conducted a comprehensive Data Landscape Overview from September 2019 to February 2020. This process included engagement with NCDHHS staff and contractors via in-person meetings; an extensive review of documents related to data access and use (e.g., privacy and security guidance, data requests, job descriptions, data dictionaries, metadata, and organizational charts); a survey of Division- and Office-specific data sharing agreements (DSAs) (which was created by AISP and the Data Office, and disseminated by Division Directors and Legal Counsel); weekly calls with the Data Office; two in-person public deliberation events with cross-department attendance of 40–50 staff; and structured interviews with 44 individual staff members, in-person and by phone. Specific questions used in the structured interviews are shown in Box 1. Interviews typically lasted 60–90 minutes each. Lastly, the Data Landscape Overview included an inventory of existing DSAs across all Divisions and Offices to better understand the terms and conditions of data access and use, as well as an overview of respondent perspectives of the current and future state of data infrastructure, governance, quality, and use. This inventory survey, shown in Box 2, spurred further engagement with NCDHHS Legal Counsel through Deliberative Dialogue.

Box 1: Discussion Protocol for Structured Interviews with NCDHHS Staff

-

1. Please tell me about your work at NCDHHS and why you were identified as an important person to talk to in regard to better understanding the NCDHHS Data Landscape and Data Infrastructure needs.

-

2. What do you see as the biggest roadblock for data access and use across NCDHHS? Biggest asset?

-

3. How are the data within your Division managed? What data systems/applications/and so forth are used?

-

4. (If applicable) If you wanted to access and use data from another Division in NCDHHS right now to better understand one of your business processes, how would you start? What would that process look like? Approximately how long would it take?

-

5. Tell me your thoughts about the following topics across NCDHHS:

-

a. Trust and collaboration

-

b. Data quality

-

c. Established processes and procedures for data sharing (including legal docs)

-

d. Resources for data management, access, and use

-

e. Data management capacity

-

f. Data analysis skills

-

g. Capacity for agency leadership to make data-informed decisions

-

-

6. What are some questions you would like to answer, but cannot currently because of a lack of data infrastructure?

-

7. What would be your ideal state for data access and use across NCDHHS? What would it look like? What processes and procedures would be in place? What would NOT be in place?

-

8. Anything else you would like to discuss?

-

9. Who else should I be talking to?

Box 2: NCDHHS DSA Inventory Survey

The following questions were sent to all Division and Office Directors with the request for completion by legal counsel.

1. What types of contractual documents are used to share data among and between your Division and other Divisions within DHHS? Please upload document(s) here:

2. What types of contractual documents are used to share data between your Division and other state agencies? Please upload document(s) here:

3. What types of contractual documents are used to share data between your Division and other entities (such as contractors, university partners, etc)? Please upload document(s) here:

4. Approximately how many agreements (of all types) to facilitate data sharing are currently active between your Division and all other Divisions/agencies/external entities?

7. Measured in weeks, what is the approximate time it takes to enact a DSA (measured from when a decision is made to enter into an agreement to when the agreement is actually signed) between

your department and another DHHS Division?

your department and another state agency?

your department and an external entity (contractor, university, etc.)?

Other:

8. Please list datasets to which you currently lack access that would have a significant impact on your department. Please include the department/agency that you believe owns these data.

9. Which of the following best describes formal structures within your department for managing and analyzing data?

Data and analytics are managed by a dedicated team at the department level.

Data and analytics are managed by a dedicated team(s) at the Division level.

Data and analytics are managed by a dedicated team(s) at the project level.

We do not have a formal structure to manage data and analytics.

Other:

10. Anything else you would like to share?

2.3. Deliberative dialogue with legal counsel

The DSA Inventory Survey (Box 2) was initially sent to NCDHHS Division and Office Directors with a request for their Legal Counsel to complete. While this survey was intentionally simple, the responses and lack of responses (due to an inability to complete the survey based on an absence of information) created a sense of urgency across the Department for Legal Counsel to engage in this work to improve data sharing. Whereas many data sharing initiatives are driven by analysts and executive leaders, we were committed to incorporating the perspectives of Legal Counsel from the beginning. This presented a challenge, as Legal Counsel in large institutions often carry high workloads that necessitate a primary focus on risk mitigation and a reactive rather than proactive approach to data sharing efforts. However, by using the Inventory Survey as a tool to demonstrate the need for legal data sharing templates and an enterprise approach, along with the inherent risk of countless data sharing approaches across the department, we were able to start engaging Legal Counsel through Deliberative Dialogue.

We relied on Deliberative Dialogue methods to generate “purposeful and evidence-informed conversations” with Legal Counsel about their perspectives and experience navigating intradepartmental and interdepartmental data sharing (Plamondon et al., Reference Plamondon, Bottorff and Cole2015, p. 1529). The goal of Deliberative Dialogue is consensus and collaborative decision-making, with emphasis on authenticity, comprehensiveness, integrity, legitimacy, and responsiveness (Plamondon et al., Reference Plamondon, Bottorff and Cole2015). As such, in fall of 2019, we invited all members of the Office of General Counsel as well as Division-specific Legal Counsel to an initial meeting with core members of the Data Office. We introduced preliminary findings of the Data Landscape Overview and developed a proposed process and next steps for co-creating an intradepartmental legal framework. Legal Counsel had the opportunity to “opt in” to the process, and ultimately, all Legal Counsel agreed to support the work. A smaller core group of Legal Counsel committed to regular meetings to review current and potential legal frameworks for data sharing and, eventually, to co-create a new legal framework for NCDHHS. This group met biweekly from September 2019 to March 2020, paused meetings during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, resumed a regular cadence from February to June of 2021 to finish the legal framework and, as of this publication, continues to meet as needed and hosts an annual in-person retreat with NCDHHS Legal Counsel and the Data Office to review and make updates to the governance and legal framework.

While the legal framework was being developed, these small group meetings generally followed a structured agenda, where we discussed problems, potential solutions based on what had or had not worked across the Department previously, and national models that could be used to inform action. For example, one problem identified through the DSA Inventory Survey was that legal agreements were being signed by staff who did not have the authority to sign an agreement. Our collaborative analysis determined that the core issue was staff not knowing their role—specifically, who is a data owner (has signatory authority), data steward, or data custodian. We addressed this problem by asking staff to complete an inventory of their high-value data assets and list individual names next to each of these roles (North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, 2023c). This approach has been used successfully in other departments, specifically in the State of Connecticut, to clarify and operationalize roles (State of Connecticut, 2022). To discuss and generate solutions to these types of legal problems, we relied on the expertise of those in the room while also drawing from AISP’s national network of experts to pose potential solutions based upon existing models of successful cross-sector data sharing and integration (Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy, 2021). Since 2007, AISP has regularly convened Legal Counsel, including two national legal workgroups on data sharing and integration, and found that lawyers prefer to talk to lawyers (Petrila et al., Reference Petrila, Cohn, Pritchett, Stiles, Stodden, Vagle and Humowiecki2017; Hawn Nelson et al., Reference Hawn Nelson, Kemp, Jenkins, Rios Benitez, Berkowitz, Burnett, Smith, Zanti and Culhane2022). Based on AISP’s experience, we created a range of environments for engagement around legal issues—including space for a regular cadence of meetings where participation was limited to Legal Counsel, the CDO, Data Office staff, and AISP, as well as two public deliberation events that were open to a wide spectrum of NCDHHS staff. This careful “table setting” allowed for an optimal environment to establish common understanding of the issues, conduct collaborative analysis, and to plan and take action (Cornish et al., Reference Cornish, Breton, Moreno-Tabarez, Delgado, Rua, de-Graft Aikins and Hodgetts2023).

3. Results

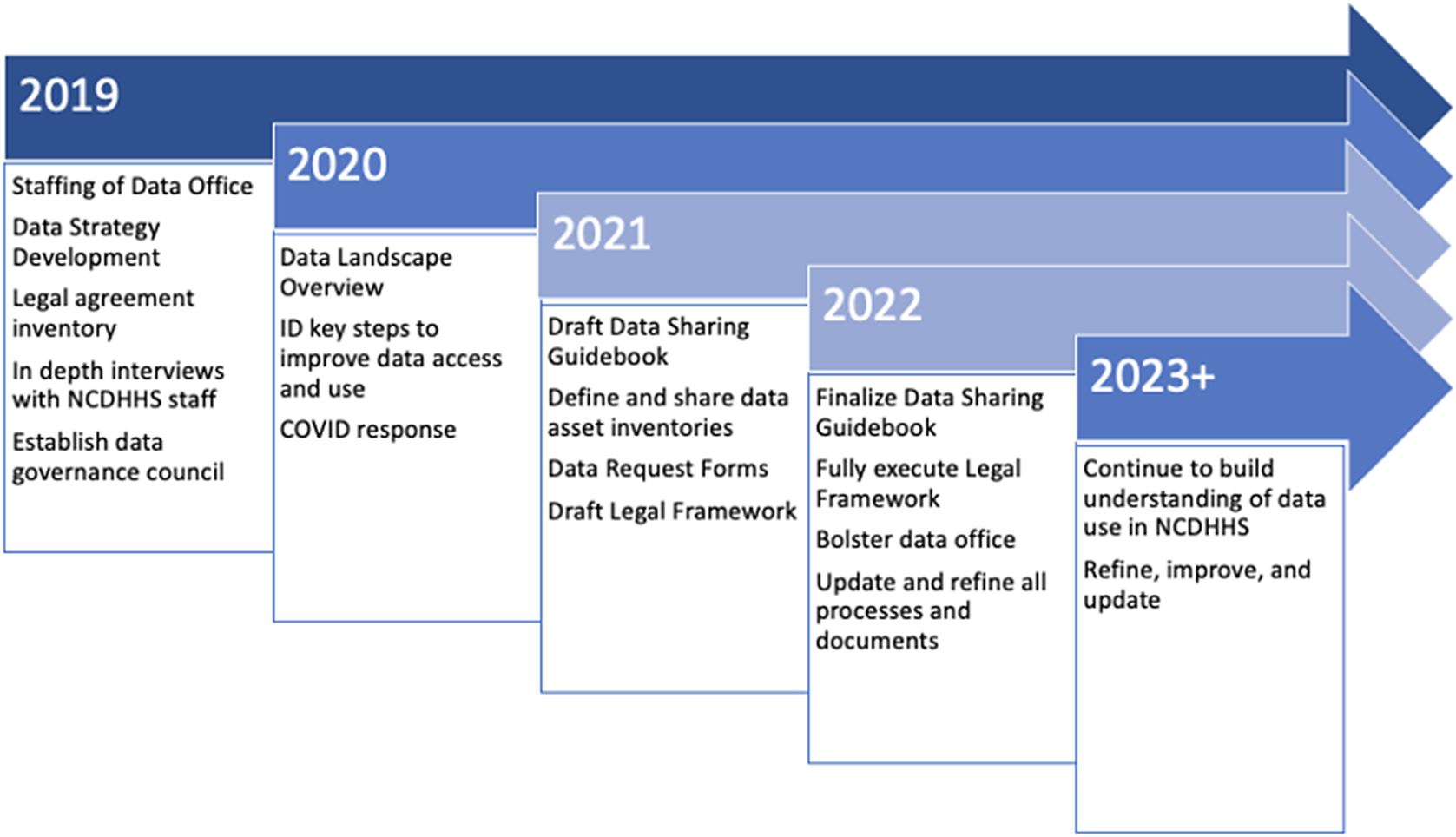

The Data Landscape Overview helped us understand what was and was not working in terms of data sharing in NCDHHS, and existing practices we could build upon to make data sharing less painful and more routine. While this information resulted in action across the five pillars (Figure 1), below we focus on four key actions related to the data governance pillar: developing a data strategy road map, creating a data sharing guidebook, staffing the NCDHHS Data Office, and implementing a legal framework. Figure 2 shows the timeline for these and other key streams of work that have been necessary to develop strong data governance across NCDHHS. It is essential to note that this work was neither easy nor simple but accomplished through 1) hundreds of hours of discussion across the disparate staff and consultants that support NCDHHS and who are committed to using data responsibly to better serve North Carolinians and 2) practicing these new processes in daily tasks and actions, iterating as needed.

Figure 2. Overview of key data governance activities, 2019–2023+.

3.1. Key findings from the data landscape overview

While we learned of specific projects where strong data governance practices were used to facilitate advanced analytics (e.g., detailed data documentation, collaborative review, well-structured DUAs with clear terms of use), this was not standard across NCDHHS. Most staff pursued data sharing through informal channels, such as existing connections to other data stewards or months-long email exchanges between a wide variety of staff. These endeavors rarely resulted in successful data sharing, due to a lack of guidance, momentum, turnover, and/or concern about possible misuse. Many staff had grown accustomed to data sharing being “impossible,” which drove a cycle of restricting data access that embedded itself into the culture. Thus, a core finding was the need to develop clear access and use procedures suitable for data across NCDHHS and templated legal agreements to support these processes. Moreover, the Data Landscape Overview clarified our imperative to standardize processes for data access and use in order to:

-

• Benefit North Carolinians: Data integration supports holistic insights that can result in better service and outcomes at a lower cost across the enterprise and ultimately place NCDHHS in a better position to “buy health” (Wortman et al., Reference Wortman, Tilson and Cohen2020, P. 649).

-

• Mitigate risks: We found that NCDHHS data were either highly restricted or unrestricted, without clear documentation to distinguish between the two. Both approaches have intended and unintended consequences that lead to risks (either missing insights or risks of privacy redisclosure).

-

• Support staff: Data access has been a pain point for staff. Staff were eager to use data in alignment with their roles and responsibilities and to not spend their time figuring out data flow for operational use.

With these imperatives in mind, we cultivated partners committed to building better processes together and engaged stakeholders in taking the four actions described next. Relying on PAR methods was critical for not only co-developing a new governance and legal framework with stakeholders, but also in changing culture around data sharing—data assets previously viewed as inaccessible are now being proactively pursued and staff are getting to “yes” with new data integrations.

3.2. Four actions toward routine data sharing

3.2.1. Developed a data strategy

We developed an NCDHHS Data Strategy (North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, 2019) that described a future state vision for NCDHHS data: Enable NCDHHS and its partners to quickly and easily make data-driven strategic and operational decisions by providing access to integrated, trustworthy, well-governed, and managed data. We aligned this vision with several NCDHHS core values (North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, 2023a) that already guided strategy and decision-making across the Department: Teamwork, Transparency, Stewardship, and People-Focused. While the data strategy was largely informed by leadership—a more “top-down” approach—we made sure that it complemented the “bottom-up” staff perspectives articulated by the Data Landscape Overview. For instance, the short-, medium-, and long-term goals identified in the data strategy directly addressed issues consistently cited by staff. In this way, the Data Landscape Overview validated leadership’s data strategy, provided valuable insights for the Data Office to plan effective implementation of the strategy, and created buy-in across NCDHHS that enabled true culture change around data sharing. The data strategy—along with the creation of the Data Governance Council in 2019—laid a framework to build collective understanding of the work required to operationalize the vision. It also provided a high-level implementation road map and timeline. Though the timeline necessarily shifted as COVID-19 reached North Carolina just three months later, we remained focused on the vision.

A major principle introduced in the data strategy is that data limitations are business limitations. To emphasize this point, we put forth specific use cases to illustrate business needs that could not yet be achieved given the existing data infrastructure. For example, we wanted to understand cross-enrollment among NCDHHS customers and which programs were under-enrolled based on likely eligibility, but this analysis was not feasible when we began in 2019. Through the implementation of our data strategy, this analysis is now possible, and routine. Providing use cases solidified what the executive leadership wanted to achieve and helped the Data Office, Data Governance Council, and NCDHHS staff visualize how streamlined data sharing processes would improve their day-to-day work.

It should be noted that the framework put forth in the original strategy document has been refined over time as the team implemented the proposed strategy. For example, the original document included only four “pillars.” Data literacy was added later as a fifth pillar, as the need for workforce training and development became clearer. Additionally, although data quality is often included as a component of data governance, it was initially broken out into its own pillar to emphasize the importance of the previously undervalued practice. As work progressed and culture evolved, consideration was given to merging those two pillars into one. Although the term “pillar” implies some level of permanence and dependency, it should not be interpreted to mean rigidity. We are building the foundation for department-wide transformation over time, informed by new insights along the way.

3.2.2. Created a data sharing guidebook

The next action step was distilling hundreds of hours of collaborative meetings into a simple tool to guide staff in how NCDHHS accesses and uses data. The NCDHHS Data Sharing Guidebook (North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, 2023b) was collaboratively created and reviewed iteratively by dozens of NCDHHS staff over the course of two years. Significantly, this document is not a policy, it is a guidebook—our best attempt at operationalizing the way we use data at NCDHHS. The Guidebook makes the case for the importance of improved data access and clarifies our data use priorities. In it, we define key terms; outline data request pathways, including forms and URLs to request data based on request type; and explain the why and how of data governance across NCDHHS. A key component of the Guidebook includes defining the term “high-value data asset” with clear directions for how information regarding these assets should be shared across Divisions and Offices by data owners and data stewards. These data asset inventories allow data owners to identify data that are critical to the operations of NCDHHS that can be used for strategic use. This inventory documents the data owner, data steward, and data custodian for each application or dataset, while also providing documentation of legal and technical restrictions of these data (e.g., aggregation requirements). It is important to note that only data that are shareable—high value and of sufficient quality—are included in this inventory and available for intradepartmental use.

As with any document of this kind, the main challenge is having it actually be used by staff, whether legacy or new hires. We know that people support what they help create, and the participatory process, while challenging, has been critical to the Guidebook’s success. However, it is important to note that several years into this work we are still regularly asked questions where the answer is, “please look in the Guidebook on page X.” To address this, annually we meet with each Division and Office during recurring meetings to provide “Guidebook 101” training to make sure staff are aware of the resource, how to use it, and how it can help make their job easier. As with all data governance work, there is always more to do as we iterate and refine processes.

3.2.3. Organized the NCDHHS data office

From its inception, a conscious decision was made that the Data Office should not fall under Information Technology within NCDHHS’s organizational structure. This decision emphasized the strategic nature of the new Office, not as a technical function but embedded in the business itself. The organizational structure for NCDHHS’s Data Office generally mirrors the five pillars in Figure 1 with data governance and quality merged under a single governance lead.

While the strategic value of the Data Office has been proven as we have successfully implemented a new data governance and legal framework, long-term challenges remain as there are no clear funding mechanisms due to the cross-agency nature of the work. Staff are largely funded with nonrecurring sources, primarily through federal grants. We remain resource-constrained but also benefit from high levels of executive support and the flexibility to staff creatively for strategic priorities.

3.2.4. Implemented a legal framework

One aspect of the data strategy described above was a recognized need to improve the efficiency of processes around legal agreements required for data sharing. While conducting the Data Landscape Overview, we collaborated with NCDHHS General Counsel, which includes attorneys committed to specific Divisions and program areas based on subject matter expertise and proficiency. Across program areas, Legal Counsel expressed clear frustration over the historical lack of engagement around data sharing. Not unique to NCDHHS, Legal Counsel were often only included at the end of a long process to share data. With this in mind, we intentionally centered their expertise throughout all streams of work.

We started the work of crafting a strong legal framework with the intent to build organically on existing processes rather than being directed by “innovation.” We identified what was working well—we had impressive data flow for specific projects, minimal issues with respect to incidents and breaches, and strong support from staff at all levels, particularly executive leadership (Cooper and Cohen, Reference Cooper and Cohen2021), to address barriers to data sharing. We spent several months identifying data request pathways and determined that every request could be categorized across the following seven pathways: operational (the majority of requests across NCDHSS), research, audits, public records, legislative, legal affairs, and interdepartmental (beyond NCDHHS but within state government; Hawn et al., Reference Hawn Nelson, Kemp, Jenkins, Rios Benitez, Berkowitz, Burnett, Smith, Zanti and Culhane2022, p. 11–13, 32–33).

Once these pathways to request data were clarified, we determined permissible use of data based upon purpose, usage, and requestor. Clear guidance from Legal Counsel was imperative, as the regulatory landscape for permissible use is fluid and formidable. We also needed input from expert users who understand the nuances of the data to form accurate insights, and we needed to ensure that data were stored and transferred safely and securely. This meant that staff had to “know their role”—specifically, whether they were the data owner, data steward, or data custodian (Hawn et al., Reference Hawn Nelson, Kemp, Jenkins, Rios Benitez, Berkowitz, Burnett, Smith, Zanti and Culhane2022, p. 16). We defined these roles, their respective differences, and the importance of each in ensuring use were legal, ethical, and a good idea. Then, we operationalized these roles by creating high-value data asset inventories for each Division and Office, where key data assets were documented along with each asset’s owner, steward, and custodian. This documentation also clearly lists signatory authority for data use. We found that using this document could prevent the hundreds of emails it would have previously taken to formulate a productive data request.

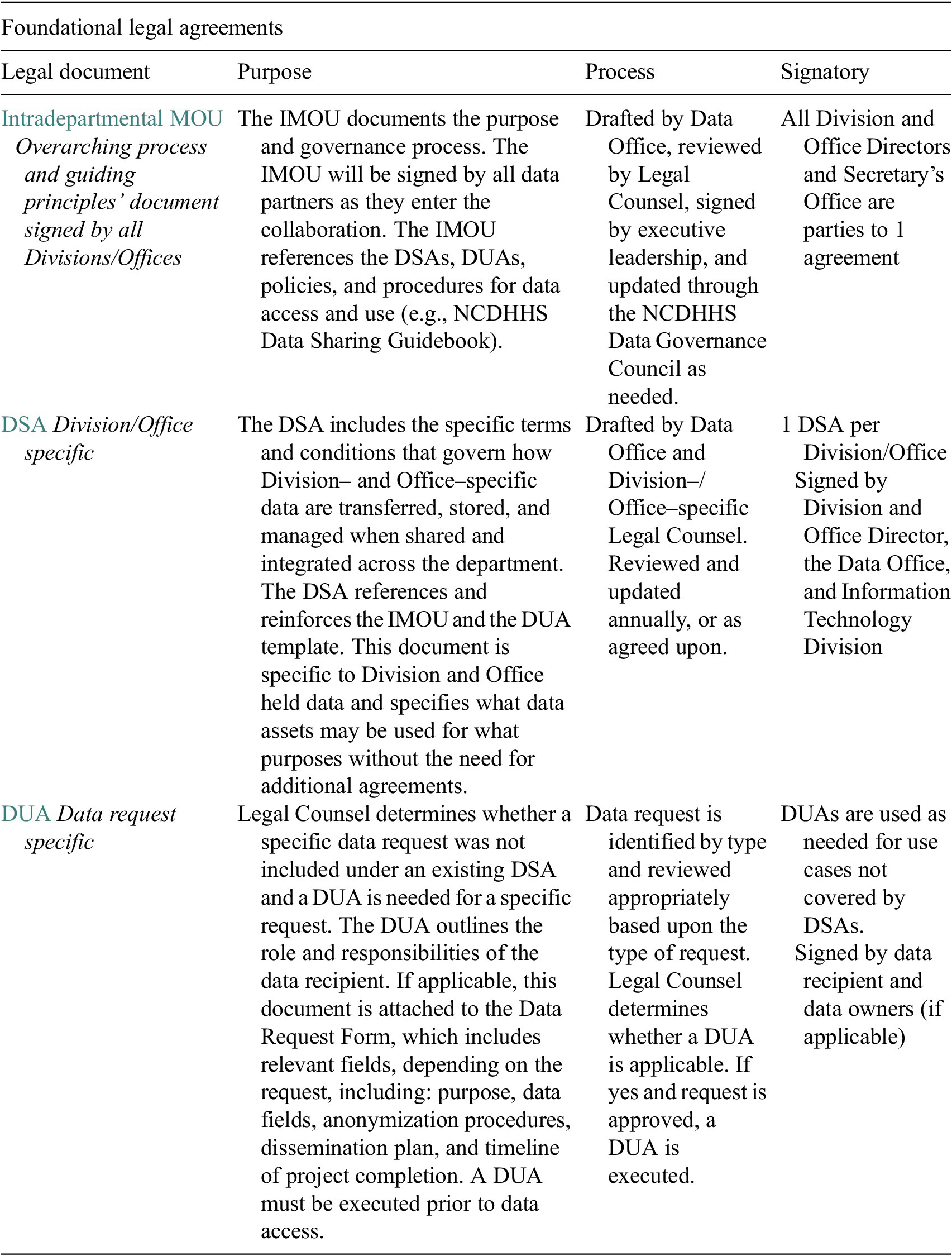

The last step in creating our legal framework was crafting a suite of interlocking, adaptable documents to address threshold legal concerns and inevitable tensions of risk versus benefit, as described in Table 1. Executing the Intradepartmental Memorandum of Understanding (IMOU) began with a memo from our Secretary in fall of 2021. Due to the collaborative nature of our work, every member of the General Counsel’s Office had written, redlined, and edited the agreements. By the time the IMOU was sent to executive leadership for signatures, the approval was already in place and we were able to execute the IMOU in under five days.

Table 1. Overview of foundational legal agreements used with NCDHHS

Source: Reproduced with permission from the NCDHHS Data Office. Legal agreements are hyperlinked within the NCDHHS Data Sharing Guidebook, https://www.ncdhhs.gov/about/administrative-offices/data-office/data-sharing-guidebook

In December 2021, we began drafting the Division- and Office-specific DSAs. The Divisions holding our highest value data assets were prioritized for completing their respective DSAs first. This was a significant commitment from data stewards, executive leadership, and Legal Counsel, and momentum proved challenging. Following a strong and unambiguous directive from Secretary Kinsley in April 2022, this work was reprioritized by Division leadership and the DSAs for these five high-value Divisions were fully executed by May 2022. All legal agreements are hyperlinked in Table 1.

4. Discussion

Building a strong governance and legal framework is hard work—there are no quick fixes for navigating the legal, technical, and cultural challenges, and there is no arrival point at which these frameworks are “done.” However, we are now seeing the fruits of our labor as analytic projects that support NCDHHS’ mission to “buy health for North Carolinians” come together more readily, with fewer pain points and more holistic engagement of staff. Even amidst a pandemic (Harmon et al., Reference Harmon, Fliss, Marshall, Peticolas, Proescholdbell and Waller2021), executing our data governance and legal framework has empowered NCDHHS to better access, exchange, and use highly restricted data to support critical initiatives. Below we discuss three such use cases.

4.1. Use case 1: linking prescription drug dispenser data with vital records

One of the first data use cases presented to the newly formed Data Office was linking death and dispenser data to better understand connections between prescribed controlled substances and opioid deaths. The ability to answer questions about controlled substances dispensed prior to a person’s death, even when the certified cause of death was illicit drugs, is critical to identifying potential intervention points. For example, even among illicit drug deaths (e.g., heroin/fentanyl), it is important to know whether the person had also been legally dispensed prescription opioids in the weeks and months prior to death. Evidence from other states showed that individuals dying from drug overdoses had many different channels for accessing drugs and these distribution patterns were important to understand in order to provide more comprehensive prevention measures. However, this analysis necessitated access to protected, siloed data: the prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) and vital records. It was not until the Data Office supported these types of data linkage projects that this specific project regained traction and moved forward.

The Controlled Substance Reporting System (CSRS), North Carolina’s PDMP, is a clinical database that collects information on dispensed controlled substances to improve patient care and safety, avoid drug interactions, and identify the need for substance use disorder services. North Carolina law severely restricts CSRS data. Illegally accessing or using CSRS data a felony that can carry a presumptive 18-month prison sentence (North Carolina General Assembly, 2013). Because the actual (versus perceived) risks and legal pathways for internal data linkage were historically not well established or understood, CSRS data were particularly difficult to access, and the data remained underutilized for actionable analytics, public health surveillance, and response and prevention activities.

To provide support, the Data Office collaborated with key stakeholders to determine the appropriateness of the data and use case and, employing the legal framework, successfully facilitated lawful, useful linkage between death certificate and dispensing data that continue to provide valuable insights. For years, the NC Injury Epidemiology, Surveillance and Informatics Unit had suggested the idea of linking opioid deaths with additional datasets was sought to help understand the full trajectory of individuals most at risk and identify potential new prevention opportunities. Yet, without a centralized data sharing plan in place, these attempts to link data from disparate programs and systems were virtually impossible. Conceptually, many of the key partners were onboard, yet when the specific ask to share and link data was sought, numerous roadblocks and barriers would come to the forefront. Specifically, data stewards would revert back to data protection/data security policies that were historically used to prevent data from being shared or used in this manner. Legally sound data use remained central throughout, and the Data Office served as an advocate and vested partner in getting to “yes,” where historically, risk aversion might have made the inquiry a nonstarter or, ultimately, impracticable.

4.2. Use case 2: identifying patients at risk for self-harm

NCDHHS program staff working with the North Carolina Violent Death Reporting System (NC-VDRS) enlisted the Data Office to help link suicide deaths with inpatient hospital discharge data to identify missed opportunities to assist patients at risk for future self-harm. Researchers have found that people who died by suicide often had many interactions with healthcare systems in the 12 months prior to their deaths. These prior interactions can stem from a wide range of presentations, such as behavioral and/or mental health hospital admissions that could have been further assessed, screened, and potentially referred for additional services or treatment. Therefore, NC-VDRS staff wanted to identify fatal suicide attempts following discharge for self-harm from an inpatient hospital setting. The only way to do this was to combine data from the VDRS with North Carolina Hospital Discharge Data, which include information from more than 125 hospitals across the state. Though hospital discharge data had previously been provided to NCDHHS’s Division of Public Health in de-identified form for surveillance purposes, identifiable data would be needed in order to link completed suicide attempts with hospitalizations for self-harm.

Here too, there was historical and cultural reluctance to utilizing data outside of previously defined contexts. The State Center for Health Statistics (SCHS) (data stewards of the hospital discharge data) had long-standing and understandable data privacy concerns around the linkage of individual-level hospitalization records and the potential for redisclosure of such sensitive data. In addition, there is inherent risk of these types of data being used to over-surveil populations that are already highly system involved. Using frameworks outlined in the NCDHHS Data Sharing Guidebook, however, the potential risks versus benefits of linking suicide deaths with inpatient hospital discharges were thoroughly considered before proceeding. Furthermore, the newly stated priority to leverage data assets as part of the NCDHHS Data Strategy created momentum for this use case to move forward. The Injury Epidemiology, Surveillance and Informatics Unit within the Division of Public Health submitted a data request that was quickly reviewed by the SCHS leadership team in fall of 2019. Data privacy concerns were addressed through the legal framework by clearly outlining where benefits outweighed potential risks for this use case and assuring that only the data needed to successfully link cases would be shared. Ultimately, the necessary parties approved of sharing the requested data for the intended purpose and the project advanced within 10 weeks—much more efficiently than would have previously been possible. As a direct result of reorienting the culture around data sharing, some findings from this project have already been published (Proescholdbell et al., Reference Proescholdbell, Geary and Tenenbaum2022) and an additional publication is in progress. Validating our approach, this project is being adopted as a public health practice and surveillance model across the state, an outcome hard to imagine in the not-too-distantpast.

4.3. Use case 3: enabling cross-enrollment analysis for targeted outreach

Many residents of North Carolina who are enrolled in one service or benefit are eligible for others, but for any number of reasons, are not enrolled in those other benefits. This hinders positive outcomes for individuals and leaves federal dollars on the proverbial table that should be flowing to North Carolina, both improving outcomes for that individual and serving as income for businesses who provide that service or product (e.g., grocery store items purchased via Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) funds). Medicaid, SNAP, and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) were all housed in different Divisions across NCDHHS—the Division of Health Benefits, Division of Social Services, and Division of Public Health, respectively. NCDHHS wanted to identify who was receiving benefits from one or two of these programs, and also likely eligible for, but not enrolled in, either or both of the others. Doing so through the old system would have required either several different DUAs or a complicated four-way agreement (between the three Divisions and the Data Office whose staff would perform the analysis) plus an agreement with vendor partners who worked on data modeling required for the integration. All of these avenues would have required several months and hundreds of hours of effort from staff and Legal Counsel.

Fortunately, the Divisions in question were among the first across NCDHHS to be incorporated into the new legal framework. Each Division had signed its own DSA, which enumerated the “high-value” data assets it housed, and the common use cases for which those data assets could be shared with other Divisions or Data Integration Staff with only limited additional documentation (i.e., a two-page “Operational Data Request Form” specifying what data elements were being requested and for what purpose). Medicaid, SNAP, and WIC enrollment were all included as shareable assets. In addition, this cross-enrollment analysis use case specifically addressed three stated goals for prioritizing data use: 1) to advance health equity by reducing disparities in opportunity and outcomes for historically marginalized populations within NCDHHS and across the state, 2) to help North Carolinians end the pandemic, control the spread of COVID-19, recover stronger, and be prepared for future public health crises with an emphasis on initiatives serving those communities most impacted, and 3) to build an innovative, coordinated, and whole-person—physical, mental, and social health—centered system that addresses both medical and nonmedical drivers of health.

Using the new legal framework, Operational Data Request Forms were completed and reviewed by Legal Counsel from each Division to confirm that this use case would fall under the terms of its existing DSA and then a DUA was executed. This process was completed in record time for the Department (one month) due to the clear articulation of the data ask enabled by the Operational Data Request Forms and alignment of this ask with leadership priorities. A DUA was finalized within one month. The result of this data sharing process was a cross-enrollment dashboard showing the actual enrollment size of Medicaid, SNAP, and WIC, as well as the potential enrollment size based on those who are likely eligible but unenrolled. This in turn has enabled pilot outreach programs to contact potentially eligible residents to let them know about these services and how to enroll.

5. Conclusion

The work of data sharing and integration in a large state agency is more relational than technical. It requires embedding data governance into the everyday actions of staff and building trust and understanding among colleagues. Technical approaches change at rapid speed, so governance must be flexible and include open channels of communication vertically and horizontally. Our aim has been to collaboratively develop and implement processes that are sustainable over the long term rather than enforce directives without generating buy-in across NCDHHS. Though every context is unique and requires a tailored approach, our work provides a framework and model for how state agencies can begin implementing effective, collaboratively developed, and robust data governance. This work is not easy, but we have seen the payoff when staff find new possibilities for data sharing and are able to undertake impactful analyses that were previously considered off limits.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Amy Hawn Nelson [[email protected]], upon reasonable request and approval from NCDHHS.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge those who have supported data strategy at NCDHHS and who provided invaluable insights throughout this project: NCDHHS Office of General Counsel, including Lisa Corbett, Julie Cronin, Pam Scott, Lotta Crabtree, and Raj Premakumar; NCDHHS Division of Public Health, including Virginia Niehaus; Secretary Kody Kinsley, and Secretary Mandy Cohen; NCDHHS Data Office, including Hayley Young, Lorelle Yuen, and Katherine Lockett; NCDHHS Data Governance Council; Division and Office Directors; and Charles Carter, Sam Gibbs, and Jennifer Braley.

Author contribution

A.H.N., P.H., S.P., and J.D.T. involved in conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, and resource acquisition; A.H.N. involved in data curation; A.H.N. and J.D.T. involved in funding acquisition, methodology, supervision, and visualization; A.H.N. and S.Z. involved in project administration; A.H.N., P.H., S.Z., S.P., and J.D.T. involved in writing original draft; and A.H.N. and S.Z. involved in writing the review and editing. All authors approved the final submitted draft.

Funding statement

This research was conducted by university-based researchers in collaboration with the NCDHHS as a research–practice partnership. Core funding was provided by NCDHHS through a contract titled, AISP Technical Assistance to Support Cross-Agency Data Sharing for NCDHHS (2019–2024). Hawn Nelson is Research Faculty at the University of Pennsylvania, and this technical assistance grant has funded 7–18% of her salary as a member of the NCDHHS Data Office Team.

Competing interest

A.H.N., P.H., S.P., and J.D.T. are all employed by the NCDHSS and receive compensation as staff or consultants. P.H. is a member of the Legal Advisory Workgroup for Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy at the University of Pennsylvania. S.Z. declares no competing interests.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.