How can I engage my body, which is my space to live, which is my state of being alive? … We as artists, as Black women artists … we are trying to confront and create answers against this state of death. This state of brutality. (Luciane Ramos Silva)Footnote 1

Precarity is very important because I come from Guadeloupe; it's a little island. The history of Caribbean islands—English, Spanish, or French—it's one catalyzed by colonization and slavery. That is chaos. Destabilization. One person decides another person is not a person. My reality is, all the time, precarity.… And I think, like from dance—for example in Guadeloupe it's Gwoka, Martinique it's Bèlè, Haiti it's Vodou, Puerto Rico it's bomba—we have one foundational gesture: it's chaos. It's out of balance. But, in Guadeloupe, when I observe this dance, I think dance is a solution for the world. Now. Because the dancer never falls. They receive chaos, instability, destruction, but they never fall. That is a philosophy. Harmony and equilibrium? No. That is not life. (Lēnablou)

Precarity really speaks of a state of in-betweenity, a state of suspense, a state of not finding ground. And for me it's very much linked to nature. (Yanique Hume)

I always have to look at my ancestors and what they went through. If they could have survived for me to be here today, … I have no choice but to … fight and struggle and to keep that going so that, what we know about life, as opposed to the death that surrounds us, will live on to struggle another day. (Halifu Osumare)

[Puerto Rican bomba] has provided a space for not only looking inward, but provided the structures to care for each other, and to listen to each other, and to provide networks of bringing supplies and connectivity, and getting people water, getting people food at a very most basic level. (Jade Power Sotomayor)

Maybe we should be in precarity to really give importance to life and have a certain balance between you and your neighbor, you and your country, you and your space, you and yourself too. And also, for an artist, being in precarity is a powerful source of inspiration and creation. (Sephora Germain)

Precarity as potential, almost. [W]hen you think about ritual—moving from one stage to the other … the fact that there's this liminal precarious space that you move through. And if you seize that opportunity and you seize the power of that space, then there's potential to rewrite and rescript and reinvent yourself for something new. But there is also this opportunity to look back and remember the heritage of resilience and resistance that you've received, and [to] bring those two things together is the power of that space. (Rujeko Dumbutshena)

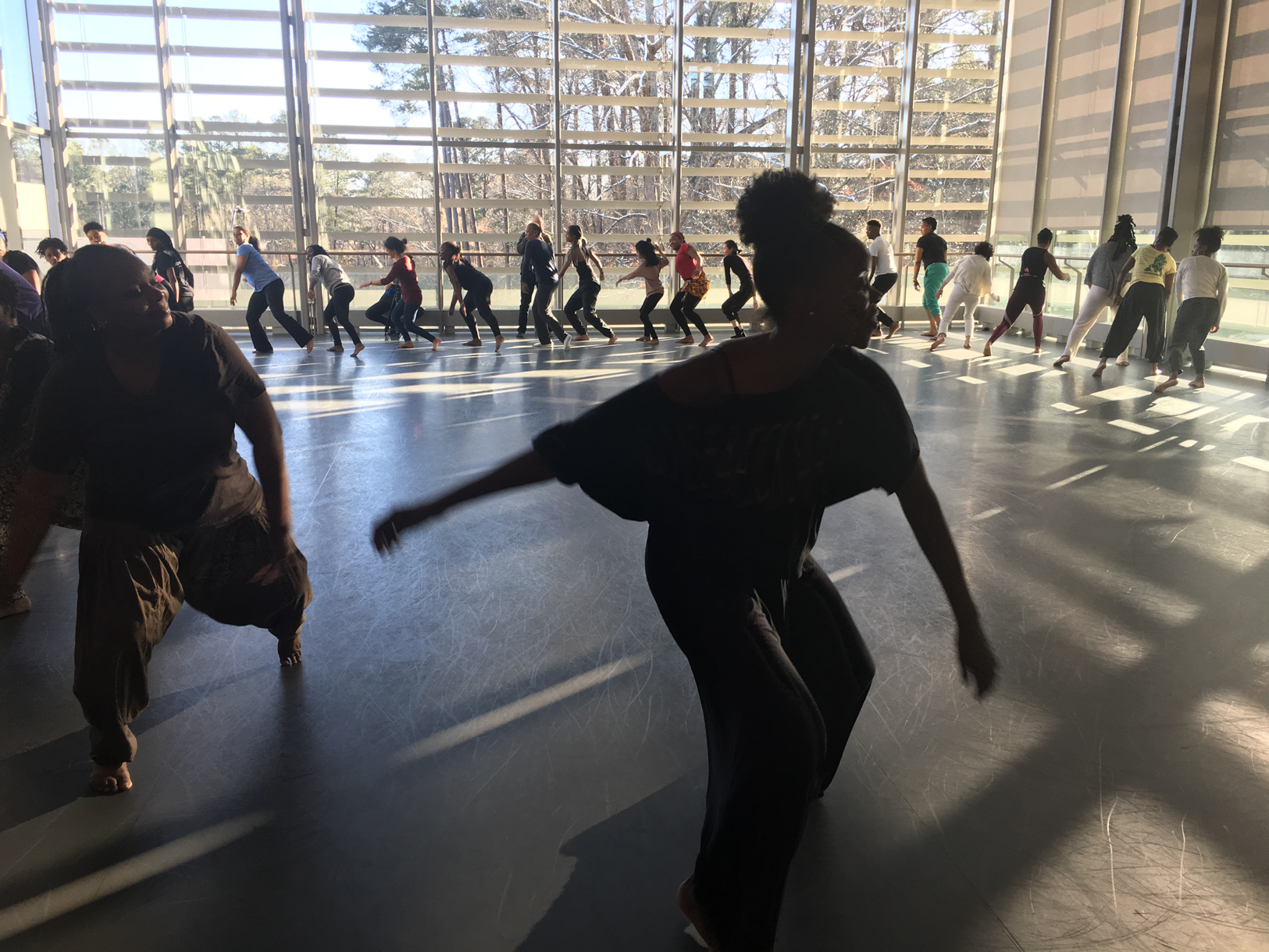

How do African and African diasporic dance-music-song-philosophies fuel specific communities of practice and instigate critical corporeal praxes across varied yet contiguous landscapes of duress? These women's statements illuminate the ways precarity serves as a foundational ecology for African diasporic women's creative emergence. These insights arose in conversation during the 2020 iteration of Afro-Feminist Performance Routes, a focused residency that nurtures embodied dialogues centered on African-derived dance practices and their intersections with gender, femininity, womanhood, femme, and feminisms. Biannual gatherings at Duke University in 2016, 2018, and 2020 hinged on the work of Lēnablou (Guadeloupe), Rujeko Dumbutshena (Zimbabwe, United States), Sephora Germain (Haiti), Yanique Hume (Jamaica, Cuba, Barbados), Jessi Knight (United States), Halifu Osumare (United States), Luciane Ramos Silva (Brazil), and Jade Power Sotomayor (Puerto Rico, United States). Convened by Dasha A. Chapman (Davidson College), Mario LaMothe (University of Illinois at Chicago), Thomas F. DeFrantz (Duke University), Ava LaVonne Vinesett (Duke University), and Andrea Woods Valdés (Duke University), these gatherings and the artists they bring together have created spaces for sharing practices, movements, insights, and time together across diasporic differences and continuities.

Over three gatherings and five years, the concept of Afro-Feminist Performance Routes was considered, challenged, and ultimately reconfigured.Footnote 2 How useful was our initial, quite wordy framework? What might Afro-feminist, or Afro-feminine, open up, and what might it preclude?

When we came together in early 2020, the articulations of this cohort cohered as “AfroFem”: a framework that could hold the multiplicity, the contradiction, and the potentiality of these Black women artist-scholars’ embodied visions. As the artists began to mobilize as AfroFem, we saw what the concept conjured: relational-yet-unified power, lineage, sacred knowledge, ingenuity—balancing energies and path-carving labors.

Our most recent gathering, Diasporic Dis/Locations, took place at Duke University in alignment with the Collegium for African Diaspora Dance (CADD) conference in February 2020—a mere three weeks before the United States went into pandemic lockdown. The first question posed to the artists during their shared roundtable conversation asked for reflections on the ways they were moving through “our increasingly precarious times.” Excerpts from their statements open this article. Although intensified authoritarianism, climate change, political disenfranchisement, staggering gaps in wealth and health, and incessant state violence already characterized the period in which we had been convening (2016–2020), the months following February's gathering brought such injustices and instabilities even more to the fore through what is now often referred to as the “twinned pandemics” of COVID-19 and systemic racism, which disproportionately affect Black women. What these AfroFem artists made clear, however, is how diasporic creativities and embodied practices illuminate the ways precarity is not simply a twenty-first-century phenomenon. Black women and African diasporic subjects have long been using embodied methods to navigate the dispossessions and “chaos” of colonialism, enslavement, and their many afterlives—the practice of artfully living in “a state of death.” Lēnablou sees how Guadeloupean Gwoka and other indigenous Caribbean practices provide lessons for surviving everyday instabilities that assault bodies through time, space, and experience. Luciane Ramos Silva highlighted the life-and-death stakes of living in Brazil, as Sephora Germain brought us to Haitians’ durational intimacy with instability. Jade Power Sotomayor recognized how Puerto Rican bomba can, in fact, instruct and support modes of collective survival through its practices of mutual aid and social organization. Yanique Hume brought us to the sacred energies and lessons integral to embodied relationships with nature. Halifu Osumare reminded us of the legacies of living-towards-life inherited from her ancestors, and the resource of an integrated mind-body-spirit practice she learned from Katherine Dunham. Rujeko Dumbutshena reflected on precarity's connection to ritual, which makes space for transformation and alignment with the divine while at the same time draws on ancestral legacies of resource and resilience. To value what our current moment teaches us requires that we acknowledge the way Black women have long drawn from African and African diasporic aesthetic philosophies to improvise choreographies for self-making and collective well-being, connection across times and spaces cleaved apart by the ruptures of structural violence.

Photo 1. AfroFem 2020 Cohort. From left: Jade Power Sotomayor, Lēnablou, Luciane Ramos Silva, Sephora Germain, Yanique Hume, Rujeko Dumbutshena, Halifu Osumare. Screenshot from video by Sarah Riazati.Footnote 3

What follows is a scripted simulation of conversations generated in roundtables, workshops, performances, and interviews, as well as around dinner tables and during late-night chats. We've woven together the artists’ statements under two umbrella themes, “embodied philosophies” and “contours of diaspora,” to highlight the relationship between creative practice and lived experience, between singularity and collective, between precarity and the everyday, between AfroFem and becoming.

AfroFem Cohort*

Lēnablou (Guadeloupe) is considered an avant-garde artist for creating “Techni'ka,” a contemporary teaching technique based on Guadeloupe's Gwoka rhythms and dances. Lēnablou is a doctoral student and the founder of the Center for Dance and Choreographic Studies and the Compagnie Trilogie Léna Blou and the Larel Bigidi'Art, combining training, creation, and research.

Photo 2. Rujeko Dumbutshena (right) dances with another, as witnesses celebrate their embodied dialogue. Zimbabwean dance workshop at Duke University, February 2020. Photo by Alec Himwich.

Rujeko Dumbutshena (Zimbabwe, United States) is a dancer, choreographer, and teacher of what she terms “neotraditional” Zimbabwean dance technique. Rujeko Dumbutshena teaches and performs throughout the United States and is assistant professor of dance at the University of Florida.

Sephora Germain (Haiti) is one of the few leading female contemporary Haitian dancers with an international performing career. She is a soloist of Jeanguy Saintus's Ayikodans (Haiti). Sephora Germain also has a local commitment to teaching dance and yoga to youth in Port-au-Prince.

Yanique Hume (Jamaica, Cuba, Barbados) is associate professor of Caribbean cultural studies at the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill. Yanique Hume is also president of KOSANBA: a scholarly association for the study of Haitian Vodou, and a professional dancer/choreographer who works through Afro-Caribbean sacred forms.

Jessi Knight (United States) is a dancer, teacher, and choreographer based in North Carolina, United States. Jessi Knight, with her sister Christina Knight, is the cofounder of Knightworks, which fosters intentional community that engages, addresses, and is accountable to its audience and its community.

Jade Power Sotomayor (Puerto Rico, United States) is assistant professor of theater and dance at University of California, San Diego. Jade Power Sotomayor's work engages Latinx performance in relation to the politics of race, ethnicity, remembering, and community. Jade Power Sotomayor not only researches but also teaches and performs bomba.

Halifu Osumare (United States) is professor emerita in the Department of African American and African Studies (AAS) at the University of California, Davis. Halifu Osumare has been a dancer, choreographer, arts administrator, and scholar of Black popular culture for over forty years. With a PhD in American studies from the University of Hawai'i at Manoa, she is also a protégé of the late renowned dancer-anthropologist Katherine Dunham and a certified instructor of Dunham Dance Technique.

Photo 3. Lēnablou instructs in using all parts of the feet to dance Bigidi. Workshop at Duke University, February 2020. Screenshot from video by Sarah Riazati.

Luciane Ramos Silva, PhD (Brazil) is a dancer, choreographer, educator, anthropologist, and cultural organizer based in Sao Paolo, Brazil, who works in a mode she calls “diaspora body,” which brings West African and contemporary Brazilian movement modes in conversation. Luciane Ramos Silva also edits one of Brazil's all-Black culture publications, O Menelick 2° Ato.

Embodied Philosophies

How do you imagine an embodied philosophy that feeds your practice? In what ways do you cultivate collective possibilities and the presence of the individual in your work?

Halifu Osumare: I don't have to “imagine” because my philosophy (values and motivations) and my practice are one and the same. I don't create anything that is not driven by my developed philosophy of living, guiding my artistic practice, which includes both my writing and my choreography. My philosophy is all about engendering a collective well-being, and my individual creative practices keep me in balance so that I might aid my communities to grow and evolve. My embodied Africanist practice allows me to innovate as an individual in order to foster community growth. My creative individuality and my community's evolutions are interrelated and enhance each other.

Jessi Knight: I imagine an embodied philosophy to look like an integrated approach to the balancing act that is creating/living art and the life that exists outside of the practice and the actual studio space. It looks like living the intentions of my work: creating meaningful, authentic, and thoughtfully connected art that exists as a testament of my experience. It means constantly asserting the validity and necessity of acknowledging the practitioner (or student of the practice) as whole, that the beliefs, feelings, dreams, intuition, heart, mind, and body are all critical pieces of embodied knowing and thus embodied practice.

Lēnablou: The Guadeloupean dancing body breathed the following philosophy into me. This body has a very particular way of moving in space and in its utterly unpredictable relationship with rhythm. I call this approach “Bigidi'art.” It indicates an asymmetrical body in permanent rupture. The body dances the harmony of disorder. The dancing body of Léwòz (one of seven traditional dances found in the Gwoka) is in a permanent imbalance, always at the edge of the penultimate fall, yet it never falls. For over twenty-five years, Bigidi has fueled my work's foundation, both in my choreographic and pedagogical creations. The Bigidi spirit is currently a real philosophy of life, as much in a personal and spiritual perspective as on a collective level. The popular local maxim “Bigidi mè pa tonbé”––which means that you can stumble but you must never fall––is my creative backbone. I am strongly convinced that the histories of slavery and colonialism experienced by Guadeloupe cultivated in our body and mind the ability to bounce back, to adapt constantly, and to remain standing. Bigidi is not only an art of the body but also a lifestyle, one of resistance.

Rujeko Dumbutshena: I have lived most of my life as an alien resident, the culture and country that I am from growing ever more distant. Paradoxically, the country in which I live as an alien brings me closer to my own. The US milieu cultivates my, often unconscious, practice of self-discovery. Finding comfort and “home” within, I have become detached from actual geography and adhere to the steady process of self-realization. Living within my displacement feels like a spiritual journey in which my practice of African dance (specifically from Zimbabwe, Guinea, Senegal, Mali, and Congo) keeps me rooted in a cultural context to which I feel I belong. My embodied practice is my vital constant, which keeps me grounded to a sense of place while allowing me the liberty to explore and adapt the ancient forms into a language that can speak in my unique expression. Along with the practice of African dance comes its inherent ability to cultivate community. My dance practice gifts the feeling of closeness while simultaneously demonstrating the specificity of self. I believe African music and dance, in its evolution across continents, has retained that exact purpose. It makes the reality of collective expression truly and easily come alive for me. I am most inspired by the vitality of pan-African connection and collaboration, and the infinite ways it presents itself through diasporic performances on and off the stage.

Yanique Hume: The question of embodiment becomes particularly germane when paired with the concept of memory and history. Within the context of the Caribbean, the geographical locale that provides a source of inspiration and where I ground my practice, these two ideas (memory and history) carry an enormous weight. The heaviness comes from the reality that the past and that which we are called to remember is often painful and fragmentary. As sites of the earliest and also protracted colonial/imperial experiments, our histories have been irrevocably interlaced with that of our oppressors and at times silenced from public reckoning. For many early explorers of these territories, we were a space devoid of history, a new world to be discovered and exploited—in a word, a tabula rasa of which new histories would be inscribed. While for some this offered a space to reimagine self anew, for many others that were forcibly brought to populate these isles it became a space of trauma but overtime a space to also call home.

As a dancer/mover/explorer of African diasporic and in particular Afro-Caribbean dance and movement vocabularies, the body becomes a central place to work through the silences and traumas of the past while also highlighting the incredible diversity of our identities. As a Jamaican who has lived and worked in many sister island-nations, I see my journey to be one of translating and sharing the threads of continuity that reside in our shared histories. There are several layers of re-memory at stake: personal/individual, experiential, the metanarrative of the collective reembodiment as well as the memories re-exhibited by former incarnations that exist within the cellular repositories of the body. The body therefore becomes an intermediary site for the intersections of memory and reimagining healing futures. In my own practice, the work of creating art entails tapping into the embodied memories, bringing into consciousness and visibility what is not always tangible yet is energetically present. The aesthetic sensibilities that structure our innovative movement vocabularies are in constant motion and transformation and speak to the memory and history that has shaped who we are and who we are destined to become. My dance practice serves as a tool to remember to call to consciousness the elemental qualities we share as a people.

Centering my practice within the realm of the sacred presents many possibilities for cultivating collectivities while allowing the individual to also blossom. The spiritual systems that have served communities across the Afro-Atlantic are inherently participatory. They call us to assemble, to enter a divine circle—a place of intimacy, safety, and above all else, inclusivity. While occupying that space we are moved to share our innate gifts, unencumbered by an external pressure to perform. In my own explorations and development of my dance practice, I start from the premise that we all have a divine purpose and internal light that when ignited has tremendous transformative potential. Each individual has her own gifts, idiosyncratic style, that when placed in conversation with another extends the range of aesthetic possibilities and meanings. My work embodies a hybrid synergy between folk and modern idioms informed by diverse sacred systems. What emerges from this collision of expressions, histories, embodied memories, and sacred cartographies is a movement vocabulary that is both subtle and dynamic, and one that elaborates on balancing the duality of power that exists within the feminine and masculine, the mundane and the divine. Indeed, as one becomes more somatically aware, the binaries fall to the side, and in their place arises a potential for the coexistence, transcendence, and reconciliation of multiple realities at the same time.

Photo 4. Sephora Germain performs a solo from “Reflections,” choreographed by Jeanguy Saintus. Duke University, February 2020. Screenshot from video by Sarah Riazati.

Sephora Germain: Everything is in our environment and right before our eyes. All we have to do is select and channel our interests. I can say my philosophy is built on awareness of what is around us. This philosophical practice continues through a process of selection and how I exploit my reality. In the same vein, the data is quite different: in our everyday life and in the way all animals move and behave. For example, there was a powerful moment in Jeanguy Saintus's Lamentation 13 in which I had to portray a person who was perceived to be “crazy” but in actuality was in communication with the otherworldly. I had to draw inspiration from people in my environment whose inner and private lives were misunderstood. As I develop my quality as a performer, my own philosophy is built around everyday sources that can help me illustrate people's wealth of spirit and knowledge.

Luciane Ramos Silva: I think the body is intrinsically related to its context, which means the cultural context—referring to spiritual cultivation, for example—but also it means political and social context. So while dancing, we can reach sort of a balance, a “mood,” which is kind of a response, a way to deal with challenges. There is also some irony, very present in the cultural experiences of Black diaspora, which is also something that I feel present in my practice: it's a way to play, to say and not to say.

Photo 5. Yanique Hume, open and receptive, leading an Afro-Cuban Dance workshop at Duke University, February 2020. Screenshot from video by Sarah Riazati.

In a deeper sense it's important to think of the body as a system of energies. While dancing, we look to find an internal rhythm, an internal balance. This balance is also a state related to living together in community. While dancing together, we leave the status of “individual” and become “people” (pessoa).

How do you think of “feminist performance”? Is there an “essential feminine” energy that is important to your creative practice?

Yanique Hume: Feminist performance creates an alternative, breaking the normative mold of dominant representational regimes and strategies that marginalize, silence, or suppress women's realities and the experiences of those not deemed powerful. Because it is unapologetically inclusive, feminist performance extends beyond strictly women's stories to embrace other narratives, themes, and experiences, including that of race and sexualities. Daring in its approach and political in its stance, feminist performance fuses multiple media to awaken consciousness and center the gaze on the complexity of the human condition. Even with its universal tenor, the power of feminist performance for me resides in its ability to situate women as central to the human story. When I think of feminist performance as an aesthetically radical, socially transgressive, and politically subversive force, I am led to the enormous influence of Grace Jones and her ability to cross boundaries, provoke reaction, and discussion through her art practice. My own work does not follow that same trajectory of transgression, but it is inspired by the sensuous rawness of her craft and its ability to explore the many facets of Black diasporic womanhood.

My creative practice is rooted in exploring the contours of the sacred and, specifically, the generative powers of the divine feminine. I am guided by the archetypal principles of different goddess traditions and explore the myriad articulations of feminine energies through my work as a mother, priestess, teacher, performer, and choreographer. In this way, I'm clear that there isn't a sense of an essential feminine but a plurality of feminine powers that demonstrate the expansive range of our reach and potential. The work of Black feminist, activist, and lesbian scholar Audre Lorde becomes particularly useful here because, as she clearly articulates in her Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power, the erotic resides in a deeply spiritual plane as a site of creative power that is political and likewise sensual. My explorations of the sacred, while centering women, also encompasses the balanced duality of the feminine and masculine energies that dwell within us all. Through working from the space of the erotic, I am inspired to, as Haitian-American author Edwidge Danticat phrases it, “create dangerously” without inhibition, thus harnessing the power of the sensorial and experiential in the fashioning of art and ourselves anew.

Jessi Knight: My work relies heavily on the concept of the essential feminine. As a mother, teacher, and nurturer of sorts, my work could not exist in its current form without the fullness that is my experience as a Black woman/mother/artist. Nurturing those within my communities—my children, dancers, elders—is an essential part of creating work that exists, not within a vacuum but within that connective tissue that is humanity.

Rujeko Dumbutshena: Not every woman is fighting for the same cause or has the same mission, nor can one character or production speak to all women. Because of women's complexities and individuality, I do not imagine that any one feminist performance can be successful in speaking to or for all women. Feminist performance may express inequalities, oppression, or highlight women's strengths, but it must speak to women's empowerment, directly or indirectly whether explicitly or implicitly.

My images of women are reflections of myself, my ancestors, my stories. In my observation of various interpretations of womanhood in the United States, often I could not find my mother, my grandmothers, or myself depicted in the stories. It is disheartening not to see yourself represented, and it becomes an essential idea to combat this by drawing and depicting your own essential female characters. It is a personal and less political style.

Women are my primary inspiration: their voice, their movement, their power and control, their grace. In my conception of African women's stories, I want to conjure a reflection of African traditions including age-old gender conventions entangled in contemporary cultural and personal concepts as an attempt to drift between past and present. I hope to present an essence of my female performance characters dancing between upholding tradition and being fully functioning modern women, whose characters speak to and question the limits of what the patriarchy perceives.

Lēnablou: In my island, Guadeloupe, feminist performance does not have the same flavor, the same color, or the same significance as it does elsewhere in the West. We, Guadeloupean women, are perpetually in a fierce battle with life, men, and children. It might be part of the legacies that Creole women have bequeathed to me: strength and intuition. I have not felt the need to use art to brand my womanly vision of the world. I was born “feminist,” a being with a natural posture as her signature. This feminine energy to which I was introduced gives me tremendous strength to shift the tectonic plates, the traumas of slavery that are still present in the collective unconscious. I am deeply conscious that I use my art––dance, the concept of Bigidi as a foundation for my contemporary technique, Techni'ka––as a weapon sheathed with a lot of love in order to touch what is intimate about women as well as men. This feminine energy animates my reflections about the Caribbean body, to say to the new generation: do not be afraid, dare to conquer the world.

Halifu Osumare: The feminine, for me, starts at the spiritual level. The divine feminine principle in the universe is at the core of my work. The balance contained within the universal order dictates that the feminine must take its place, coexisting with the masculine—like yin and yang. But in Western societies, the feminine is often not given its full recognition, creating an imbalance on every level—cognitive, emotional, social, political, cultural. That is why African philosophical perspectives make so much more sense to me, because the feminine must be given its full glory in order to have a balanced social order and sane world. I naturally embody the sacred feminine in my creative practice because I am WOMAN in its full power, and therefore I must bring that energy forward as a part of my purpose, my work in the world.

Sephora Germain: Feminist performance enables a way of expressing with one's body what the mouth does not dare say and when the tongue is limited. It must have a “consciousness-raising” dimension for the beholder. Because, in the end, our different realities do not have the same name, but their meanings share similarities. For us performers, that restorative process is the fòs (inspirited strength) of a feminist performance. In my development as a dancer, I've encountered men who interpret lwa Danbala (subtle and sensual energies), and women who dance Ogou (a warrior's strength). Therefore, an essence is not only feminine but also masculine. This combined essence is the most important symbiosis in my practice and creation.

Photo 6. With humor, Luciane Ramos Silva brings dancers low to the ground to move in duets. Workshop at Duke University, February 2020. Photo by Alec Himwich.

Luciane Ramos Silva: I believe in the woman's capacity to change the order of things, to transform the normative structures of power into better spaces to inhabit. Thinking about any “essence” always implies a risk of not considering the multiple forms of existing as a woman. I think there's a sense of justice, balance and well-being that can be related to the universe of women. In the field of performance, the disruption of the patriarchal order (that kills not only women but also all the nonhegemonic senses of being) and the systems of knowledge, which created “bodies that matter and bodies that don't matter,” is also something that seems to be related to feminist performance as well: changing the centralities of things and criticizing the models that are far from reaching the breadth that we are as human beings. So, related to the idea of “energy,” I think feminist performance has the energy to dismantle, deconstruct, band, and sometimes laugh about the hegemonic systems that are incapable to think the idea of “difference.”

How do your embodied philosophy and creative practice engage the Afro-feminine/Afro-feminist?

Lēnablou: My bias, both in my artistic approach and in my aesthetic philosophy, was not a choice but an injunction. Above all, it was a question of deconstructing the representations of the “Black body” embedded in the minds of African-descended peoples, which mirrors European supremacy and Euro-centered thought. In my opinion, the urgency was to offer a counterdiscourse that was both philosophical and artistic, and the issue was not so much about the female or male body, but more about the “Caribbean body.” We must remember that the European settlement of the Caribbean resulted in an inhuman, violent, and degrading history––that of slavery and colonization. Therefore, the dances from these spaces bear that seal. I felt called to do a type of disobedient dance research in Guadeloupe by letting myself be guided solely by my intuition. It resulted in my invention of a new dance technique: Techni'ka and the concept of Bigidi. They both aim to defend the aesthetics of homegrown traditional dances and highlight a Caribbean worldview.

Techni'ka is a weapon of offense that thwarts all the atavisms of history, because postcolonial societies are described as a krazé society, meaning societies that are economically unbalanced, socially and racially disturbed. Moreover, I had the lingering intuition that the Caribbean knows how to move from decorporealization to reincorporation by upholding chaos as a philosophy of life. My professional background made me realize fairly quickly that there were a number of pre-determinants that went against me. My homeland, my Gwoka dance, and my female body, enclosed me in a heavenly postcard shot as a sensual, lascivious, and gentle woman or traumatized body.

As a woman and an artist, I practice disobedience by educating myself as well as the body and mind of women to rehabilitate the body and its integrity because, subconsciously, they reproduce the fabric of history: sexualized body, object of exotic beauty, while being a woman-potomitan (central pillar of the home, myth of the lonely mulatta), mother (father), and a free and independent woman (the witch and the whore).

Halifu Osumare: To engage the Black feminine does not take any forethought. It is who I am from the beginning and always. It's my first impulse for any action and drives every thought process. It is so much a part of what makes me who I am; it is difficult to explain. It is natural; it is the alpha and omega of my being. How does one explain how one breathes or how one's heart beats?

As a priestess of Oya-Yansa, Yoruba deity of The Transformative Winds and Keeper of the Ancestors, I always hold the divine feminine close to me as a source of power. As I have grown, this feminine warrior power has grown within me. Oya is my mother, and I am the child. She empowers me to do her work in the world, and I gladly obey. African peoples traditionally embody philosophy, as opposed to writing it down. As a priest and scholar, I am trained to do both. I continue the embodied practice of my ancestors, through being the knowledge and creating from that space. I also record, as much as possible, the process and the resulting creative manifestations in the world, which becomes the result of my embodied Africanist philosophy and practice.

Sephora Germain: Afro-feminism can serve as a space of exchange, and as a movement to convene, is an opportunity offered to us artists and researchers to reflect on ourselves and our practices, to express the unspoken, to meet and highlight our cultures, and share our visions on the struggle of women in the twenty-first century. As a dancer, I see in the concept of Afro-feminism not only an affirmation of my identity as a Black Haitian woman but also a commitment to engage in the good fight, the concern for quality, and total self-acceptance.

Luciane Ramos Silva: Before saying “how I” engage, I should say “how we” historically engaged the Afro-feminine/feminist (even before those terms were widespread) in our creative daily life practice. Black women in the course of history have created responses to the world, re-created structures, and strengthened their contexts through their capacity to transform and their ability to fight and care. From the women of the Good Death Sisterhood (Irmandade da Boa Morte) in Bahia, who brought liberation for Black people during slavery, or Harriet Tubman, who guided slaves to their freedom … These women found ways to transform and flow. One of the philosophies that I bring while creating dance is to embody our layers of history. So my way to inscribe myself in the world passes necessarily through the perspectives of these women who came before me. I also carry the aim to imagine forms of being, of self-writing, and of writing new worlds through the perspectives that break the movement of the exploitations, stigmas, and all kinds of destructive forms, and invest in the strengthening of autonomy, self-care, and a presence em ginga.

Photo 7. Jade Power Sotomayor teaches assertive communication in a bomba workshop at Duke University, February 2020. Screenshot from video by Sarah Riazati.

Jade Power Sotomayor: Bomba, as folks who practice it will tell you, is a way of life. It is a way of relating, listening, seeing, caring for each other. Not everyone has to like each other, but bomba, with its various points of entry and its reliance on an individual's contribution to a collective, organizes us to look inward, to each other. It honors the past, makes the present bearable, and arches towards a still-not-promised and ever-threatened future. It is a deeply Afro-feminist engagement for how it works against the grain to disrupt so much of what has produced the sickness in our world today; in Puerto Rico specifically, the violent disregard for the value of Black life, toxic gendered hierarchies, capitalist individualism, colonial dependency, environmental abuse and neglect. Furthermore, as bomba has been carried into the twenty-first century and is increasingly framed as an anti-racist, anti-patriarchal, anti-colonial, anti-capitalist practice, AfroFems have led the way both in terms of labor and vision. Driven underground by racism and the colonial legacy of disidentifying from Blackness, the “saving of bomba” in the mid-twentieth century was credited to the great patriarchs of different families who elevated bomba when to do so risked safety, social standing, material survival. Yet today we know much more about the AfroFems who carried this practice on their bodies in song and dance and sustained the domestic labors that created bomba space. We know this thanks to AfroFems who have done incredible labors to excavate, explore, and exalt the depth of the wisdoms—embodied and otherwise—that bomba offers as a critical liberatory practice. From Caridad Brenes de Cepeda, Isabel Albizu, and Nellie Lebrón to Melanie Maldonado, Julia Laporte, Manuela Arciniegas, Margarita “Tata” Cepeda, Julia Cepeda, and many, many others.

As a light-skinned Puerto Rican moving—in all senses—between the island and the diaspora, I traverse many worlds. I don't identify as an AfroFem but rather as the descendant of AfroFems. I mean that both in terms of ancestors to whom I feel responsible and who I believe sit with me in the work that I do, but also, and just as importantly, in terms of those who have taken out their machete to clear the way, to insist on the Afro-feminine/feminist as a source of knowledge, value. I think of my aging godmother taking me to find an higüera tree in an overgrown monte of my childhood. I had taken the machete to cut the vines, but dissatisfied with my progress, she grabbed it from me and efficiently hacked our way to the tree and our harvest. I am literally here because of Afro-feminist interventions, and Puerto Rico's future is largely indebted to these interventions.

Photo 8. Luciane Ramos Silva brings the group into a circle with ginga movement. Workshop at Duke University, February 2020. Screenshot from video by Sarah Riazati.

Rujeko Dumbutshena: I have vested interest in exploring the depth and power that lies within the personal, spiritual, and performative ways in which African women find and define their freedom. Their performances have the capacity to create opposition and agency and to transform their social realities, rewrite histories, reverse and subvert race and gender hierarchies.

African dance practices today exemplify the inherited resistance practices that allow for the manipulation of how these dance forms are received and understood. These practices result in the survival and continued influence of African dance forms on contemporary cultures everywhere. African dance is not only an expressive art, it is connected to the divine and results in transcendence that continues to push against the boundaries set up to undermine it. African dance gestures and action are tools I use to create ritualized action. They offer methods for radical expressivity, via the body, introducing its transcendent potential.

The communal connectivity seen in African culture and ceremony anchors me to a deeply rooted sense of self, womanhood, and place. My move away from being surrounded by a group of people who share my common cultural practices forces me to practice a self-prescribed embodiment of collective memory that disregards my immigrant displacement. Historic and cultural memories continue to exist in my body in the absence of geographic proximity and shared embodied practices. My practice involves finding agency in my displacement to redefine, to understand and remember again, who I am. My remembering, via my female body and African dance practices, broadens my cultural and self-knowing, effectively chipping away at my colonial mentality that was set on me to restrict my freedom.

Contours of Diaspora

How do you conceive of diaspora, and what does “Africa” mean to you? How do you engage its contours?

Lēnablou: I do not conceive the diaspora as a theoretical or intellectual concept, but as one of self-existence. I'm the epitome of an uprooted body who had to adjust to a new land. I am a “diasporic reinvention.” I am a spark of Africa that tells an alternative story about life, death, love, and birth. This light has been transmitted into the body, despite the tear from the original source. I have retained most of Africa due to the presence of drums, the permanence of the initiation circle, and the symbiotic relationship between the body and rhythms in the Gwoka dance. What seems essential and vital to me is to restore the link between Africa and the Caribbean. This can be accomplished as a dual objective: Caribbeans as the diasporic confetti must continue to explore their history (slavery, colonization, assimilation, neocolonization); and the African people must also discover and receive this history. The Caribbean must feed this memory, its African roots. From then on, Africa must be in dialogue with this rhizomatic culture that has grown here and there in the Americas. Therein lies the significance of increasing and multiplying exchanges via creations, theoretical concepts, performance, skills, and past and current knowledge.

Rujeko Dumbutshena: The diaspora reflects the sustained flourishing of Africanist culture around the world. It is made up of the places that inherit African culture as a result of the migration of people of African heritage. African artists living in America are part of the diasporic community with which I interact the most. In this community, I have learned how to navigate renewed being, sacrificing the familiar, holding on to traditions and customs, and traversing cultural barriers with power and grace. These African diaspora artists produce new forms of expression and impact music and dance communities around the world. The diaspora stands as a testament to the transformative resilience of cultural traditions of African people.

Africa's contours are both political and personal. On a personal level, I know I will never fully understand the depths of Africa's gravid waters. To me, African art is so powerful in its specificity and meaning, that even while skimming its surface, I gain a wealth of information. I crave its ambience to fill me when I am empty. It stirs me up, unexpectedly lighting a spark in me, reminding me of my rich Africanness. Politically, Africa's vastness is full of irony, tainted and innocent, true in its purity yet highly corruptible. It is subjected to being robbed, easily forgotten, often underrated, while sustaining itself through enduring flexibility, rearing itself into future and current popular culture via sly reappropriation.

Yanique Hume: Diaspora is a condition, a state of being in motion, in process of becoming, a generative place of in-betweenity that gives rise to incredible creative potentialities. Diaspora is not an end but a process that holds together the two poles of roots and routes—the places from whence we came and the varying trajectories of our journey as individuals, communities, and cultures. Diaspora has a particular temporality, as it is not fixed but instead brings together different genealogies of time and space. I am a product of several accumulative diasporas—a coming together of multiple narratives and identities. I am most identified with my African roots as they have helped to define the contours of my consciousness and being, but I am also a product of Asian and European legacies and also the Caribbean diaspora dwelling in different locales across the region and also in North America.

In thinking through the meaning of Africa and this notion of diaspora, the Atlantic Ocean comes to mind. This majestic body of water, untamed and expansive, stands for many as a symbol of rupture from our past, an underwater graveyard for millions who perished during the Crossing. But as M. Jacqui Alexander reminds us, not all crossings happened at the same time, neither are they once and for all. The Atlantic thus also becomes a source of continuities and connectivities, a reflective prism through which we all traverse to be reborn anew at the time of our passing. The Atlantic is the container of many hopes and aspirations and a uniting force that ties together the many cultures of the Americas with that of Africa.

Africa is the homeland of humankind, thus a site of origin for all people. However, it is not a space that has stood still, frozen in time, and it is not a space of singularity. My Africa is a potpourri of experiences, traditions, histories, and possibilities—at times a troubled place, a product, in part due to its turbulent history of cultural contact with the West—but notwithstanding the setbacks, it's a place of incredible creativity, innovation, and dynamism. Africa announces itself through its sonic reverberations, its layered polyphonic rhythms that combine different hues of motion, from the most dynamic to the most subtle. Its unpredictability, which can be a source of worry or instability, adds to its creative dynamism and hybridity.

Fluidity is at the heart of mapping the contours of diaspora and Africa. Like the Atlantic that unites Africa with its diaspora, syncopated movement creates the pulsation, the ebb and flow—tidalectics that allows me to evoke Africa's sensibilities. Beyond being a specific geographical locale, a continent of diverse cultures, Africa represents to me a particular sensibility—a feeling that manifests in and through motion. It produces its own structure of feeling that stresses nonlinearity, improvisation, coolness, and incredible rhythm. Playing with these ideas through movement and sound become instrumental in creating choreographies that are able to bring Africa into tangible presence.

Jessi Knight: The diaspora, in addition to its existence as a result of the flow of Blackness out of Africa into the world, serves as a resonance of how Black people survive/carve their way through the world, how they find footholds to keep themselves tethered to one another, to their pasts (ancestors), and looking forward to an imagined future of what could be. Engaging in its contours feels like honoring those diasporic influences in my work. I am constantly pulling back layers of social conditioning wherein white standards and aesthetics are considered the bar to which everything else is measured, while Blackness and most things Afrocentric are somehow less than.

I honor my roots, using what I know (hip-hop, jazz, undulation, polyrhythm, etc.) and what I've experienced; this is how I have found some semblance of truth worthy of being shared. While I consider engaging with the diaspora critical to my work, essential to my sense of self as a human and as an artist, I am continually being reminded of my own privilege, my own relationship with whiteness, and the muddled and imposed binary that says I cannot be more than one of these things at once.

Halifu Osumare: The reality of Africa's dispersion is embedded in all of us in this project. We are sprouts from Africa's fertile seeds cast across the globe. Naturally the sprouts become different as they grow in diverse soils, but do they have the core of the original seed? That becomes the philosophical question. I say YES! Without being essentialist, the original African seed must be contained in the assorted sprouts, regardless of the historical, economic, sociopolitical, and religious forces that were plowed into those soils. The seed of Africa remains, rearing its “powerhead,” especially through the body, even when the sprout is unconscious of that power. Katherine Dunham said dance is one of the most tenacious cultural traits that cannot be eliminated. Concepts of the Black Atlantic, diaspora, and Pan-Africanism have had their sway at different historical points, and through it all the powerhead of Africa remained, although different now in different parts of the globe. But Africa itself was never monolithic; its various peoples had to find cohesion out of the common plight of bondage. And now today, Africa itself has to recognize itself in all its discrete variances—Caribbean, South America, United States, Central America, Europe …

Luciane Ramos Silva: There is an interesting idea about diaspora related to the word “Kalunga” as a synthesis idea that broadly explains the Black diaspora as a place of action, where trajectories are marked by resistance, affirmation, and overflow. The notion of Kalunga, which comes from the Bakongo culture, a branch of the Bantu linguistic ethnic trunk and an important African presence in Brazilian culture, is a multidimensional notion whose driving symbol is vitality and dynamism. In one of its meanings, it acts as a verb expressing the idea of movement, advancement, or progress. Its lexicon is also related to the qualities of water as fluency, cleanliness, and freshness. It also designates the ancestry or ancestral memory of Black populations, as well as everything that is immeasurable and, therefore, infinite. As an ocean, Kalunga not only separates from the traumatic memory of slavery, but also becomes a link and a place of exchange. The Congo proverb “Kalunga is a great river that runs with the eyes, but not with the legs” explains this concrete and symbolic dimension that the term carries.

Photo 9. Lēnablou and Ava Vinesett (front right) play in relational instability, surrounded by dancers of all ages also exploring partnered Bigidi. Workshop at Duke University, April 2016. Photo by Dasha A. Chapman.

How do you and your work move through our increasingly precarious times?

Lēnablou: For years, at my dance center and throughout my choreographic studies, work with my dance company (Cie Trilogie), choreographic creations, master classes and conferences, I set out to transmit and disseminate Techni'ka, to offer another vision of my country, Guadeloupe, and the Caribbean. This is a pertinent question, especially because, twenty years ago, my work remained opaque for some, particularly in France and Europe. Yet given the current uncertainty of the world, the Guadeloupean philosophy of “Bigidi mè pa tonbé” (stumble but not fall) has traction: it is a being-in-the-world conceived in plasticity, fluctuation, unpredictability, and adaptability—an aesthetic of the harmony of disorder! Bigidi resonates strongly in the body and in the mind. It seems to bring a new stream of thought and art in response to today's world. As French choreographer Bernardo Montet, former director of the National Choreographic Center of Tours, states: “Bigidi is to question the land on which we rely to propel ourselves into the unknown. It is to plunge into what constitutes us deep within, in a chaos from which we come out regenerated but not unscathed. It is to uncreate to recreate.”

Photo 10. Luciane Ramos Silva finds extension and power in a Haitian dance workshop taught by Sephora Germain. Duke University, April 2020. Screenshot from video by Sarah Riazati.

Halifu Osumare: Because I am deeply centered in the power of the Afro-feminine, it anchors me in times of great turmoil. The world shifts and changes, but I am stable in my spiritual power of Blackness and the great feminine. This makes me a warrior for my ancestors and for those who are yet to come.

Sephora Germain: In my experience as a Haitian woman and artist living in Haiti, precarity remains an element of our every day. We are not only in dialogue with that sense of off-balance in our postcolonial lives, but also the last few decades have generated a slew of political and environmental degradations that impact us deeply. Instances of precarity often compel us to step back, self-reflect, and interrogate certain aspects of our life, needs, work, environment, and several other aspects of daily life. It is the same for an artist, as precarity can offer great inspiration, being a time of creation, of being able to breathe life into our woes, pains, and the expectation of a change through dance.

Luciane Ramos Silva: I was discussing with Sister Jade how we––as nonhegemonic/ subalternized people––have experienced “precarious times” for a long time. This does not mean that we are used to precariousness. (That can be a trap.) But we learn how to deal and to negotiate with that precariousness. I believe these precarious times require ginga but also practical proposals. Illuminating our systems of knowledge, to bring up autonomy as an important part of the pedagogical practice, is a way to move forward.

Jade Power Sotomayor: I want to underscore, in concert with Luciane's Brazilian ginga and Lēnablou's Guadeloupean Bigidi, that the sentiment “there is nothing new about precarity” has—in ways that are entirely unjust—led to a great spirit of autogestión in Puerto Rico. Clearly, the federal government, the colonial state, a white supremacist and misogynist power structure, is not helping communities in their moments of need, so people have increasingly looked to each other to organize survival on a small-scale level, tapping into networks of kinship and community that include the diaspora. Bomba, in its real-time execution, not only creates networks that connect people in moments of need and precarity, but the batey, as it turns people in towards each other, also holds space for grief, creativity, and joy. Dancing, drumming bodies cathartically release, craft and play, and improvised song lyrics record the stories, loves, and losses being lived.

Rujeko Dumbutshena: For decades, African cultural performances have been intentionally strategizing ways to be seen, or not, in the face of postcolonial subjugation. I look back to retrieve knowledge I have lost to bring myself, my culture, and creations out of the margins and into the forefront of our future. I am finding it more urgent to tackle Western stereotyped images of Africa and Africans by highlighting and creating performances that act as a site of action against colonial, authoritarian, majoritarian, racist ideas and practices. I appreciate how I have inherited, from my ancestors and lineage of African artists, strategic methods to subvert oppressive systems. I choose to continue to place myself within this legacy, to find the agency that is inherent in the cultural practices and beliefs found in Africa and in Zimbabwe, in particular. Expanding my knowledge and practice of dance helps me navigate my “otherness” while showing the legitimacy and power of African artists and their respective forms. I recognize that any authority I possess, I come by honestly and has been handed down to me through the resistance practices of my people, the Shona people of Zimbabwe, contemporary African artists practicing, creating, and performing in the diaspora.

Yanique Hume: The precarity of our existence takes many forms and forces us to put our bodies on the line and to use our bodies to navigate increasingly hostile and vulnerable terrains. Our rich dance traditions give us the tools to find balance in the states of imbalance through emphasizing a playful disposition. This is a point that we all have come to recognize. The aesthetic principles and philosophies of our dances are among our first teachers to ground our energies, especially in moments when we feel most insecure. My attraction and recent exploration of site-specific work in spaces of environmental fragilities and trauma have been, in part, to bring recognition and compassion to our precariousness while also encouraging us to be even more intentional in our search for solutions. Working aesthetically through the states of in-betweenity helps to restore the energetic imbalances and also injects our realities with a playful stance of malleability and hope.

Moving Together

AfroFem is a growing sisterhood with powerfully creative women. Our AfroFem sisterhood has allowed us to further center and critically reflect on our experiences as Black women living and creating within a wider circuit of intersecting African diasporic histories and movement vocabularies. It has helped us recognize the urgency of collectively excavating the knowledge of our deep embodied philosophies that have given meaning to our modes of moving and being in the world.

AfroFem as a movement helps us be more attentive to how different artistic realities can be assembled and enrich each and every member. We learn to discover other parts of the world through these amazing artists and participants. It is a way to create and maintain communities. One realizes that, even though we do not speak the same language, we remain neighbors in a dance culture that is at once Puerto Rico's bomba, Haiti's Kongo and Raboday, and Guadeloupe's Pajambel, in dialogue with other Africanist variations. These interconnections enlighten us about how we are the progenies of people who accommodated dances according to the reality of their lives and spaces. Many other examples can be cited to indicate how we draw from the foundation, and then name our dances differently. When you look closely, you see that we come from the same base; we connect at that base. Additionally, there are similarities in women's roles and challenges in all these cultures. The AfroFem struggle summarizes these common dynamics.