Shortly after their master's death in 1760, a domestic slave named Ah Han and five of his enslaved companions submitted a confession and a plea for mercy to a local magistrate in northern Yunnan Province. They had been caught, terrifyingly, between two factions of kin and enslaved persons struggling over who would succeed their master, the native chieftain Nuo Jiayou, as sole owner of all lands and persons in a sprawling native domain. Their legal plaint told of how, after the chieftain's funeral, they had been “hounded from dawn to dusk” by two of the chiefly household's high-ranking bondsmen, inciting them enter into a pact to plunder the household wealth. “For a time, these insects stupidly listened to their talk.” The party of bondsmen and household slaves allegedly broke into the boudoir of the chieftain's elderly wife through a window, beat her, and confiscated her personal property, including silver, clothing, and grain. “Later, the head manager [also a bondsman] said, ‘beating and humiliating our mistress is unpardonable.…’ These insects, fearing punishment, consequently sought refuge in the mistress's chambers to repent and seek forgiveness.” The six domestic slaves traveled to the prefectural capital with the chieftain's wife, where she presented her case to the departmental court. There, they seized the opportunity to find a litigation master to write up and present their own plaint. They ended their confession with an entreaty to “condescend to these stupid yi [uncivilized others] who know not our own errors and are easily lured into mischief; to excuse our previous crimes; and to punish the accused rebels.”Footnote 1

“How do we narrate the fleeting glimpses of enslaved subjects in the archives and meet the disciplinary demands of history that requires us to construct unbiased accounts from these very documents?” asks Marisa Fuentes in her eloquent study of enslaved women in Bridgetown, Barbados. “How do we construct a coherent historical accounting out of that which defies coherence and representability?” Put differently, how can we excavate the experiences of enslaved people from archives that systematically exclude enslaved voices, while negotiating the demands of a liberal sensibility that requires subjects to speak authentically, for themselves? Fuentes points out that while the most treasured sources for histories of enslaved women in the antebellum U.S. South have been narratives written by enslaved persons, “the very nature of slavery in the eighteenth-century Caribbean made enslaved life fleeting and rendered access to literacy almost impossible.”Footnote 2 How can we probe the subjectivity of people whose presence in the archives is rare, fragmented, and distorted? Such questions shift in shading and emphasis when taken to eighteenth-century China, where notions of voice and authorship, rhetorical strategies of the archive, and configurations of subjectivity were all very different than in the Atlantic region. Scholars who have approached the subject of slavery in early modern and modern China have shown that coerced labor and bondage spanned all social and economic realms and persisted well into the twentieth century.Footnote 3 While some enslaved people in eighteenth-century China may have had greater access to literacy than slaves in the Caribbean, their voices, sensibilities, and intentions have rarely been sought in the extensive archive. The presence in historical writing of enslaved people in China is fragmentary, their experiences infrequently interrogated, their importance for the fashioning of history seldom valued.Footnote 4

The confession of Ah Han and the five other slaves was preserved until the twentieth century in an archive of documents in the Nuo chiefly house and acquired in 1943 by the Peiping Library.Footnote 5 This document is among the least consequential in a flurry of legal plaints authored by people of higher ranks struggling over who would become the native chieftain (tumu) of the native domain (tushu) of Mulian in northern Yunnan. The muted presence of domestic slaves is difficult to discern in this pile of documents, yet the intentions, usually disguised or distorted, of key categories of bonded persons—domestic slaves, bondsmen, and bonded tenants—were clearly points of articulation which determined the course and outcome of the case. Legal plaints in what amounted to civil cases in late imperial China were deliberate studies in intention. They gathered and systematized the intentions of those they presented as their authors, and they strategically speculated on the intentions of others, including other parties to the case and the magistrates and higher judges who were the authorized readers. Artfully constructed plaints fashioned statements about intentions into readily legible narratives about the moral character of the various parties, for character was among magistrates’ surest guides as they struggled with overwhelming caseloads and ambiguous legal codes.Footnote 6 For this reason, legal documents lend themselves to a method that follows the ways intentions are avowed, assigned, and contested. Particularly when a document's principals, or assigned authors, had extremely restricted access to the courts and to literacy as conventionally defined, this might involve careful assessment of the paths their words took as they came to be materialized on paper. Though speculative, this approach has the potential to open windows into spatial experience, the production and contestation of relations, and the mutable shapes of subjectivities.

This article explores the interconnections of literacy and bondage in this native domain by tracing some of the ways the words of enslaved persons, who did not speak or write Chinese, found their way into Chinese script in the form of narrative arguments in legal plaints. In describing relations within the house that Ah Han and his fellow domestic slaves shared with the native chieftain and his wives, concubines, daughters, and bondsmen, I suggest that the sharp division between kinship and bondage that is conventional in definitions of slavery, in which slaves are persons deprived of key categories of kin, obscures the ways that kinship and bondage feed into each other in a single field of relations.Footnote 7 In the case of the native chieftain of Mulian and his household, I argue, this field of relations is structured by a scripturation of the world,Footnote 8 in which language was inscribed into the ritualized fields of law, death ritual, household space, and even the spaces of the administrative city, as kinship and servitude were reproduced. In working through ways that diverse acts of scripturation communicated among enunciated language, written language, and organized space, I follow the rich scholarship on varied modes of literacy by scholars such as Armando Petrucci and those he inspired to challenge the assumption that people who do not read and write written texts, strictly defined, are bereft of literacy's resources.Footnote 9 Taking a cue from de Certeau, I argue that this assumption obscures the ways that texts, formal, patterned, and inscribed—from recited refrains to written pages to spatial diagrams—permeate human worlds at every level, making themselves available as sources for the expansion of action and experience, even for persons who have been deliberately deprived of the capacity to read or write as conventionally defined.Footnote 10

The notion of scripturation was proposed by Roger Laufer, an historian of the book in eighteenth-century France. Laufer wanted a concept to describe all the “marks of enunciation, handwritten and typographical” that exceeded the alphanumeric.Footnote 11 Possible alternatives such as punctuation or typography were closely bounded, and they “belonged to the epistemological field defined by the writing/drawing opposition, the insufficiency of which has been obvious since Nicéphore Nièpce.” Laufer wanted to distinguish all the elements involved in the passage graphic forms, such as musical notation, cartography, photography, radiography, and computer graphics.Footnote 12 The concept of scripturation expands our sense of the field of writing beyond the strictly glottographic into the many other, often imprecise or ambiguous, marks of enunciation.Footnote 13 Here, I stretch this concept to take in some of the symbolic and analogical graphic forms that become entangled in the passage between enunciation and inscription. Broadening our sense of writing in this way can help expand the elasticity of the archive in an effort to speak to the experiences of those whom the archive has largely silenced. In that spirit, I read the archive of legal documents in Chinese through other forms of inscription: of household space, of the field of death ritual, and of urban architecture.

The dominant language in Mulian was a Loloish Tibeto-Burman language now called Nasu (or eastern Yi), spoken across northeast Yunnan and west Guizhou.Footnote 14 Though many residents in the domain spoke languages now known as Lisu, Lipo, Nuosu, Dai, and Hmong, Nasu was the language of the ruling stratum, the slaves and bondsmen who served in their houses, and the majority of the domain's bonded tenants. Nasu speakers were heir to a long tradition of writing in their own language, in a script once called Luowu (Lv̩hu Luɦo in Nasu) and now usually called Nasu or Yi.Footnote 15 Texts in Nasu script carried assumptions about what writing was and what it could do. Most Nasu texts were manuals for making differentiated social worlds by sorting out kinds of beings such as agnates, affines, ritualists, bondsmen, slaves, spirits, and ghosts. Nasu textual practice repeatedly framed the act of writing, theorizing the powers of writing to remake relations among beings. Nasu script was intensively diagrammatic. Texts written on paper were re-inscribed into the earth as fields of social beings, framed within houses, surrounded by territories, crosscut by cosmic lines of force. The experience of Nasu textuality, shared in different ways by all the litigants in this case, likely heightened their awareness of questions about what writing was and what it could do as they sought to compose legal documents in Chinese. I suggest that many were doing other things with writing than can be read directly from the surface of the documents they produced.

Two descriptive arguments emerge from my outline of this legal case. The first concerns a group of fourteen men in a category of bonded persons particular to native domains, called toumu in Chinese and mɔ in Nasu, which I have translated as “bondsmen.” This is an argument about writing, and it illustrates the point that kinship and bondage should be seen as informing each other within a single field of relations.Footnote 16 Though they were accused of rebellion against the chiefly house, I will argue that these bondsmen were actually attempting to write back into being the relation of chiefly descent upon which the reproduction of the chiefly house depended and on which all their own relations of kinship/bondage rested. In participating in the legal struggle over chiefly succession the bondsmen were taking advantage of expanded access to legal writing afforded by the Qing legal system to elaborate upon a foundational task of Nasu ritual scripturation: the work of writing ancestry and descent into existence.

My second descriptive argument returns to Ah Han and the other five domestic slaves (jianu in Chinese, kutɕ’i in Nasu) who confessed their involvement with this group of rebel bondsmen. This is an argument about reading. It illustrates the point that reading and writing are complex human skills, often available even to those who cannot use pen and paper, and involving the coordination of forms of scripturation across different planes of inscription. I follow these slaves through the streets of the administrative city as they searched for a translator and a litigation master to compose and submit their plaint. I speculate that though the city was alien to them they were partially competent readers of it, having been guided through many diagrammatic analogues as they served in their master's house and at his funeral. This competency is visible in their properly composed petition, submitted to the magistrate's clerks and accepted by the court.

I begin with a brief introduction to the place that slavery in so-called Yi communities (which include Nasu communities) has been assigned by Chinese social science and historiography. Then I outline the initial set of claims in the case of chiefly succession from Nuo Jiayou and look at the semantic and spatial practices that divided different categories of person in the chiefly house. This leads to my reconsideration of the intentions of the fourteen “rebel bondsmen” who precipitated the case. After this, I return to the domestic slave Ah Han and his five enslaved colleagues, tracing their movements through the city streets from the departmental yamen, where their mistress was confined, to the city pond, where they might have found their litigation master. In conclusion, I briefly describe the case's denouement and aftermath, as slave babies became chieftains and a chieftain became a military slave.

“SLAVE SOCIETIES”

Throughout the socialist period, and to a degree in the present, Chinese social science treated “Yi society” as a living “slave society.” In the 1950s and 1960s, teams of ethnographers and linguists were sent to non-Han communities throughout China to determine the ethnic composition of the new nation.Footnote 17 Nasu and a host of other peoples were incorporated into a new Yi (彝) nationality. Socialist-era studies of “Yi society” demonstrated the evolutionary story of human history inspired by Lewis Henry Morgan's Ancient Society and developed by Friedrich Engels in The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State. Ethnographers of the socialist era discovered primitive communism in a few places in south and west Yunnan, feudalism in Tibet, and slavery in between, in the Liangshan ranges of southern Sichuan and northern Yunnan, among people now called Nuosu and categorized as Yi. Harvard-trained anthropologist Lin Yaohua (Lin Yueh-hwa) was a prominent organizer of the ethnic identification project. In 1944, Lin had traveled into the core region of Liangshan, dominated by militarized clans of high-status Nuosu subject to no formal system of subordination to the Qing or Republican states. Lin's report on his expedition carefully examined relations between “black Lolo” masters (nzyemop and nuoho clans) and “white Lolo” bonded tenants and household slaves (mgapjie and gatxi strata).Footnote 18

Though Lin and other early investigators regarded slavery as a timeless cultural attribute of Nuosu communities, Joseph Lawson has recently outlined the long and violent history of mutual captive-taking between Nuosu and Han that shaped institutions of bondage in the region. Qing military forces took large numbers of Nuosu captive in raids and created a system of native guard-houses (yi ka), where Nuosu chieftains or their sons were held as hostages. Nuosu took Han captives and sold them through the Liangshan region, where they were absorbed into the gaxi stratum of slaves.Footnote 19

Outside the core Liangshan region, most so-called Yi communities were under regular administration or subject to native hereditary chieftains, and they were not involved in cycles of mutual captive-taking. Yet, largely due to these early investigations, systems of bondage distinct to the core of the Liangshan region became the representative characteristic assigned to the new Yi nationality. After slaves in Liangshan were manumitted in 1956, scholars of the ethnic identification project gathered first-hand accounts of slaves’ experiences of captivity and liberation. Ethnographers repeatedly described the endogamous “class system” of the Liangshan region and made slavery, its many cruelties exhaustively detailed, into an explanatory key with which to interpret every aspect of “Yi society.”Footnote 20 In popular and administrative discourses, Yi became the most “backward” of China's nationalities. Though backwardness (luohou) was technically a reference to the evolutionary theory of social development, in practice it denoted a general absence of moral and civilizational virtues. The cost of this characterization for those called Yi has been enormous, particularly for Nuosu but also for many others, including many communities where slavery was rare or unknown.

Scholarly descriptions of remnant “slave societies” among non-Han peoples displaced slavery from modern majority Chinese society.Footnote 21 Slavery was used to distinguish “Yi society” from modern Han societies at every opportunity, and Yi slavery was taken to open a window onto the slave system of ancient China.Footnote 22 Yet slavery was ubiquitous in modern and early modern China. The Qing conquest developed a Central Asian system of military servitude in which huge numbers of slaves were bonded to ruling houses. As they invaded north China, the Manchus distributed captured Chinese to high-status households where, as bondservants, they were assigned to agricultural production and menial labor.Footnote 23 Bondservants were organized into military companies and battalions in the banner system; their descendants became the household slaves of princes and staffed the imperial household's enterprises.Footnote 24 Beyond bondservants, enslaved persons were present in every social stratum and occupational sector. Criminals were condemned to serve as military slaves in the conquests of Central Asia; people of both sexes were enslaved as prostitutes to serve urban populations and military garrisons; domestic slaves served in wealthy households as servants, laborers, accountants, and rent and debt collectors; maids were privately purchased as children to do menial labor, including sexual labor, until they could be married off; concubines were purchased by the relatively wealthy; wives were bought and sold by the very poor.Footnote 25

It is clear that inquiries into slavery in so-called Yi places must be re-embedded in the long and complex history of bondage in China. Yet it is also clear that Nuosu and Nasu did not adopt institutions of slavery from their Chinese neighbors. Systems of bondage were very old institutions in the region, with cognates throughout the Tibeto-Burman-speaking places to the west and north. Fan Chuo, the ninth-century Tang chronicler of the Nasu-dominated border regions between the Nanzhao kingdom and the Tang empire, described communities ruled by aristocratic patriclans, the na, supported by subordinate farmers (quna) and dependent artisans and farmers (sujie). Domestic slaves (zesu) were mainly war captives.Footnote 26

During the tenth century, a na chieftain named Ávì Áʋo conquered northern Yunnan. His descendants were enfeoffed by the first kings of Dali, successor to Nanzhao, as chieftains (buzhang) of one of Dali's thirty-seven border provinces. Known as the Lv̩hu (or Luowu) chieftains, Ávì Áʋo's successors ruled the region that became Wuding Prefecture through the Yuan and most of the Ming, until 1567.Footnote 27 We know little about the structures of coercion through which these potentates commanded warriors, accumulated treasure, and enforced bondage. Yet we can surmise that they were founded on the chiefly lineage's capacity to forcefully perform sovereignty. A pair of fifteenth-century inscriptions on a cliff at the center of the Luɦo domain displayed two parallel sources of sovereignty. In this monument, a late-Ming Lv̩hu chieftain used Nasu script to assemble a lineage reaching into the ancient past and to stitch that lineage to sources of sovereign ancestral power embedded in the landscape. She used Chinese script to display the parallel sovereignty granted by the imperial court in titles, honors, and regalia.Footnote 28

The Ming colonization of the Yunnan-Guizhou plateau transformed slavery in Nasu domains. In his history of the Shuixi region of Guizhou, John Herman argues that colonization brought warfare, economic transformation, intensification of land disputes, and the introduction of Chinese institutions of slavery, which all led to an increase in the economic importance of slaves and a consequent swelling of their numbers.Footnote 29 As millions of Han immigrated into Nasu domains during the late Ming and the Qing, the most powerful native chieftains, such as prefects (tu zhifu) and pacification commissioners (tu xuanweisi), were replaced by regular administrators, and imperial officials exercised increased surveillance and control over the smaller native domains that remained. During the Ming-Qing transition, Nasu chieftains consolidated three such minor native domains in the northern mountains of Wuding Prefecture: Mulian, Sadian, and Huanzhou.

Sources that can throw light on the social structure of Qing native domains are rare. The legal documents in the case of Nuo Jiayou's succession allow a unique glimpse into the “dialectic between alienation and intimacy” that animated relations among the various categories of person in Mulian.Footnote 30 Even in this archive, however, enslaved people are caught sight of mainly in passing, as they convey words and goods from one superior to another. The plaint by Ah Han and the five others is the sole document in which domestic slaves can be seen frontally, addressing their superiors under their own (transliterated) names. Yet many other categories of persons held as slaves and bonded as kin also populate this archive, showing the chiefly realm to be a layered network of bonded relations extending from the lowest enslaved child to the dead chieftain himself.

DRINKING WINE AND SMEARING BLOOD

At the core of the dispute was the question of whether the chieftain Nuo Jiayou had called fourteen bondsmen to his sickbed to entrust them with his final will and testament. The chieftain's long marriage to Lady An had produced a daughter but no sons. Eight months before his death, he had taken Lady Tang, the recently widowed wife of his paternal cousin, as his only concubine, in line with the levirate—the rule that a man should marry his brother's widow to keep her from destitution and preserve the lineage property. The twenty-two-year-old Lady Tang was not pregnant. If her husband knew he was dying, Lady An testified, why would he allow his will to be arranged by rebels and child slaves (younu)? If he had been rendered so dimwitted by illness that he could not write, then who among them could have written it down? Any will should have been witnessed by the Nuo lineage elders and the chieftain's sisters and passed to two managing bondsmen to sign on their behalf. Yet the four key lineage elders had been away in the prefectural city, and the sisters lived elsewhere. Moreover, the fourteen bondsmen could produce no written will. “It is clearly a trumped-up situation!”Footnote 31

For their part, twelve of the fourteen bondsmen testified that seven days before his death Nuo Jiayou had revealed to them that a baby born of a domestic slave named Shen was his son. The chieftain named the baby Xianzong (“manifesting the ancestors”) and entrusted the bondsmen with a written will adopting him as the chiefly heir. The bondsmen prepared for their master's funeral, announced it to his agnates (zu), and sent messengers to his affines. The chieftain's three sisters, the Ladies Nuo, arrived with their husbands. The senior husband was Chang Shousi, chieftain of the neighboring native domain of Sadian. With “secret blandishments,” he duped Lady An into cooperating with an evil plot. He shut the slave girl Shen and her baby up in a room, not allowing her to take charge of the funeral—her right as the heir's mother. After the funeral, he sealed the house's central gate while his allies collected and inventoried the silver, grain, and land contracts. Twenty-seven days after the funeral began, the gate was finally opened, and the bondsmen entered. They freed Ms. Shen and the baby and checked and recorded every item of property, giving the contracts and money to two of their number for safekeeping and turning over the hemp and grain to two domestic slaves, Ah Han and Ah Di.Footnote 32 They feared that Chang Shousi was planning to marry his son to the chieftain's daughter uxorilocally, giving the Chang family control of the Nuo realm.Footnote 33

Chang Shousi's own account, cosigned by the other two husbands, was very different. Chang testified that when the funeral was over the affines returned to their homes, while the Ladies Nuo stayed on to complete a month of mourning. (“We wanted to return,” the sisters testified later, “but younger brother's wife [Lady An] repeatedly begged us to stay, so we delayed.”)Footnote 34 The month had nearly passed when the slave Ah Han appeared at Chang Shousi's gate in Sadian domain. He had traversed the mountain range between Mulian and Sadian in the night. According to Ah Han's account, Chang Shousi wrote, fourteen of the chieftain's slaves (jiannu, meaning the bondsmen) had savagely plotted together, drinking wine and smearing blood (chaxue). Together with Lady Tang, they had taken up weapons, crowded through the window of Lady An's boudoir, and beat her with fists and feet. Lady An fled weeping to the residence of the Nuo sisters. The rebels targeted the considerable property the Ladies Nuo had retained in their brother's domain. They seized 3,400 liang of silver left to the first Lady Nuo, Chang Shousi's wife, which her brother had taken charge of. They stole 600 liang that the third Lady Nuo's husband, Sha Jinfeng, had “returned” to his wife (probably a dowry paid to him and given to her as personal property). Ten sets of fur clothing with beautiful head ornaments were also missing. The bondsmen blocked the path to the Nuo sisters’ residence and mounted a rigorous guard. “When rebellious slaves dare this much in the bright light of day, where is the law of the land?”Footnote 35

And then there was the testimony of the six domestic slaves: Ah Han, Jun Shen, Ah Fei, Ni Da, Zhe Zhi, and Ah Di. They confessed that they had “stupidly” listened to Qiu Maocai, head of the faction of fourteen bondsmen, who regaled them with tales of all the silver stored in the house. They had “smeared blood” (chaxue again) with the bondsmen and Lady Tang in a conspiracy to plunder the chiefly house's property. But when Qiu Maocai offered them each six liang of silver, and when the managing bondsman (guanshi laoren) Li Tingbi advised them that beating and humiliating Lady An could never be pardoned, they saw their error, took fright, and sought refuge with Lady An in the Nuo sisters’ residence to repent and seek forgiveness. Lady An delegated some to watch and hinder the rebels and two to appeal to the Nuo agnates to rescue her. “Who could anticipate that Lady Tang would discover this, tie up these two men, beat them, and lock them up in a dark room?” Lady An sent Ah Han to flee in the night to alert her affine Chang Shousi.Footnote 36

When conspiring to do evil from the perspective of their betters, enslaved persons in Mulian were often accused in written Chinese of “smearing blood.” Locally this idiom was usually written chaxue 插血, with the very common character cha 插 substituting as a localism or minor error for the specialized sha 歃. In classics, such as those by Mengzi and Sima Qian, shaxue meant to seal an oath by smearing the blood of an animal or human sacrifice over one's mouth. In Mulian, “smearing blood” was usually paired with “drinking wine,” and evil conspiracies always involved both animal sacrifice and drinking.Footnote 37 In Nasu places, ceremonies marking treaties or alliances all required blood sacrifice. In the largest such rite, each party to the agreement contributed a chicken, and all together contributed an ox. The ox was killed with an axe, and its skin was removed and draped over a wooden frame lengthwise. Each party burrowed under the skin, tail to head, as though passing through the body and emerging from the mouth. Each then drank a bowl of “blood wine” (sɯ ɳʂ’ɯ̏), a cocktail of the blood of the ox, the blood of the chickens, and alcohol.Footnote 38 The local ceremonies of alliance that the phrase “smearing blood” translated were technologies for creating new forms of relationships—not stable relations of descent but contingent relations of affiliation; relations not of categorical hierarchy but of negotiable equality.

When Chang Shousi accused the fourteen bondsmen of “drinking wine and smearing blood” and when the six slaves confessed to “smearing blood” they were mobilizing a deep anxiety, shared by native chieftains and their overseers in the Qing state, about the foundations of the unstable alliance that was the native chieftain system.Footnote 39 Ever since the Ming conquest of the Yunnan-Guizhou plateau, native chieftains there had been granted limited autonomy in return for harnessing their native (tu) populations, thought to be naturally troublesome and rebellious. This control was founded upon the hierarchies of bondage within native domains, which all turned on the fulcrum of chiefly descent. In Nasu places, blood (sɯ) was a ubiquitous metaphor for patrilineage. New relations of affiliation created through smearing blood threatened both the existence of this native domain and the overarching order that employed native domains to divide uncivilized peoples (yi) from civilized, tax-paying citizens (hua).

SEMANTICS AND DIAGRAMS

The sudden fluidity of relations signaled by accusations of smearing blood was reflected in the strategies litigants in this case used to position others in categories of bondage. The most ambiguous category was mɔ, usually rendered in Chinese as toumu. This institution appears to have been common to all Nasu native domains and many others.Footnote 40 I call these persons “bondsmen” in analogy to the bondservants (baoyi/booyu) who served the Qing imperial household. Like Qing bondservants, bondsmen can be compared to both the palace eunuchs of medieval China and the palatine slaves of Central Asia, particularly the nökör of the Mongol khans of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries who occupied extremely varied roles as military commanders, administrators, agents, and specialists of various kinds—an arrangement that may have been emulated in the native domains of the southwest after the Mongol conquest.Footnote 41 Bondsmen comprised the core of a native chieftain's household and administration, serving as prime ministers, militia commanders, tax collectors, estate managers, household stewards, accountants, enforcers, and attendants.

In Mulian, the institution of bondsmen inherited its character from the administrative forms of the Ming-dynasty Lv̩hu native domain, which the Nuo chieftains of the Qing approximated on a smaller scale.Footnote 42 In 1956, ethnographers of the ethnic identification project briefly occupied the chiefly house in Mulian. Locals outlined the chiefly administration for them. In their account, a minister assisted the chieftain in all affairs and commanded the militia. A Chinese-language secretary handled correspondence. A chief steward handled financial affairs, and an assistant steward managed household life. An overseer and his assistant dispatched labor on the chieftain's private estates. Twenty attendants passed on the chieftain's messages. Two foresters managed the domain's very large tracts of uncultivated land. Most of these persons inherited their positions, and they all lived in the chiefly house; they were all the mɔ or toumu.Footnote 43

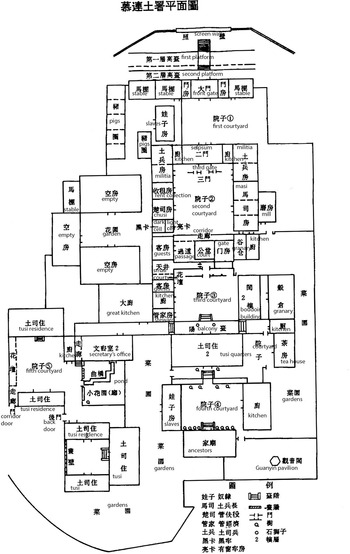

While this account may have sketched out the skeleton of an actual administrative structure, it can also be read as an idealized diagram of social roles and statuses of the kind which, in dynamic relation with the sedimented experiences of personal relations, anchors the dialectical structures of kinship and bondage. The ethnographers living in the chiefly house in 1956 seem to have intuited this diagrammatic character, for, with the help of people who had worked in the house, they created a careful plan of the residence, labeling each room with its category of resident (see Fig. 1).Footnote 44

Figure 1. The chiefly house in Mulian as diagrammed by ethnographers of the ethnic identification project. Source: Zhang Chuanxi, “Yunnan Yizu Mulian tusi shiji buzheng” (1995: 371; English labels added).

Their drawing structures the house around five courtyards, outer to inner, as though from the perspective of someone entering the front gate and working her way through layer after layer of spatially organized relational categories: up the broad front staircase and through the main gate into the first courtyard, surrounded by stables, pigsties, and quarters for domestic slaves, then through a second gate to a corridor flanked by rooms for militia and a third gate into the second courtyard. A three-room residence for the minister sat on one side of this courtyard facing a smaller residence for the overseers, along with a room for collecting rent and two jail cells, one with a window the other a “dark cell” without windows. Past the jail, the corridor led to the court, where hearings were conducted, with guest rooms to one side. Then there was a third courtyard, flanked by a residence for the stewards on one side and a two-story boudoir (guilou) for the chiefly wives and concubines on the other. Behind the boudoir was the granary, a common arrangement in humbler Nasu households, where senior women were responsible for regulating the flow of grain through the house. The end of this courtyard was occupied by a two-story residence for the chieftain, with a balcony bedecked with stone lions. Then another gate led to the fourth courtyard, with rooms for domestic slaves on the side and the hall for the ancestors at the end, fronted by eight tall columns. Off to the right was the fifth courtyard, and residences for the chieftain's daughters clustered around a garden and a pleasant carp pond with a winding stone bridge, with the archive room managed by the Chinese-language secretary on the floor above. Kitchens and gardens were distributed throughout. The house was designed to regulate the categorical placement of residents, dividing outer categories from ever more inner ones, from pigs at one end to ancestors at the other. The twenty or so attendant bondsmen and forty domestic slaves, with rooms at both outer and inner ends, were unplaced and in motion throughout the house.

It was not that the house rigorously separated classes of persons or even comprehensively filtered their contact. It was simply that the frames and planes of walls and doorways and their arrangement into repeated series of outside, gate, courtyard, inner room, provided material support for the conceptual work of sorting slave from bondsman, bondsman from chiefly concubine, and so on. The litigants in this case argued ferociously over the line that separated bondsman from domestic slave, replacing the ambiguous term toumu with terms that were more specific but just as problematic. Lady An contemptuously accused the fourteen bondsmen of hardly being chiefs (touren), merely being slaves (jianu).Footnote 45 A group of village headmen (houtou) testified that the fourteen were indeed slaves (jianu) who, having received their master's benevolence for generations, were now repaying him with rebellion.Footnote 46 Another group of bondsmen, calling themselves “managing chiefs of external affairs” (wai guanshi touren) insisted that, while they themselves had handled tasks for the Nuo chieftains for generations, the fourteen rebels were merely newly recruited tenants (dianhu), passing themselves off as toumu to write official reports.Footnote 47

The walls between slave and bondsman, or bondsman and chiefly family, were of interest to everyone in the domain, since structural failure here might shift any of the other lines that crossed and bounded the domain, dividing its various status of person. In a vivid illustration of this, a group of six village headmen, representing a tract known as the “thirteen lower villages” in the southern part of the domain, took note of the chaos in the chiefly house, including the news that fourteen “rebel slaves” had broken into Lady An's boudoir in a bid to make a slave baby the chiefly heir. In light of this, they petitioned the magistrate to remove their villages from the native domain and place them under regular administration.Footnote 48

WRITING DESCENT

The rupture triggered by Nuo Jiayou's death had become general, and fault lines shifted across several planes: a spatial plane of walls, gates, courtyards, and chambers in the chieftain's house; a semantic plane of terms for kinds of persons, rendered mobile by translation between languages; a narrative plane focused on the character or morality of particular people; and a legal plane. The legal plane was key, of course. It was empty of much actual content: the magistrate would make only one decision of consequence, unrelated to who would become chieftain, as we shall see. The legal was a ritual plane on which everything else was projected. It provided a language (written Chinese), a restricted vocabulary (bureaucratic legalese), a structure for linguistic content (the narrative form), boilerplate to surround the content, and a long series of ritualized procedures which ended in the display of a legal document on the yamen's bulletin board where all participants could read it or have it deciphered for them.

Revising the terms of bondage required a rough convergence, where a shift on one plane took hold only by precipitating shifts in others through a system of written relays. Thus, the broken window of Lady An's boudoir on the spatial plane precipitated a struggle over translated terms for categories of bonded persons on the semantic plane, which drove competing accounts of events, character, and morality on the narrative plane, all projected through procedures of selection and combination onto the formally bounded screen of the legal plane. The animating energy of this magmatic topography was the intentions of all parties involved, all focused on altering or stabilizing particular relations of kinship and bondage, and all reflected through the prism of others’ interpretations. Yet relays between planes always deflected, dispersed, or transposed these intentions. No single line of intention can be traced through the case from beginning to end. No person involved got just what he or she wanted—or seemed to want from the perspective of others. Nevertheless, the key to understanding the structures of coordination between kinship and enslavement revealed in this general rupture is to continue to ask what the participants, particularly the least powerful, wanted.

In Lady An's view, what the fourteen bondsmen wanted was obvious. They were conspiring with Lady Tang to steal as much of the household property as possible on behalf of her wealthy Nasu father, Tang Hongxu, seen transporting eight mule loads of silver out of Mulian.Footnote 49 The magistrate interrogated the bondsmen twice in the departmental yamen's court. It seems to have been traumatic for them. They did not speak Chinese, and they suspected Chang Shousi of suborning their translator. They listened as they were accused of beating and insulting Lady An, not daring to open their mouths. Afterwards, they submitted a plaint to say what they could not say in court. “The child born of Ms. Shen is truly the scholar Nuo Jiayou's bone and blood,” they said. The chieftain “evilly and cruelly did harm by not mentioning whether he did or did not have a son.” “We attest that we are no more than loyal victims in this affair. We obeyed our master's order to foster the orphan, achieving instead this crime.” “All this wounds the heart and cuts to the bone! Heaven and earth cannot tolerate it, the sages grow angry, the ancestors gnash their teeth!”Footnote 50

Without standing on any status distinctions, the bondsmen were claiming to be mitigating the harm their master had inflicted on the chiefly house and realm by not announcing an heir. In their account, their task was to produce an heir to continue the chiefly lineage and defend the domain from being devoured by Chang Shousi and the other affines. In other words, it was to reproduce their entire world—the house in which they had been raised, outside of which they had no place, no kin, no status, and no livelihood. In their two plaints they resorted to writing repeatedly that the baby Xianzong was indeed, and without question, the son of Nuo Jiayou. They discovered during their interrogations that there was little chance the magistrate would hear their claims, yet they persisted.

A clue as to why can be found in their prompting plaint: “These small ones,” they said, “invited the agnates to the funeral on the first day of the fourth month.”Footnote 51 Despite their complaint that Chang Shousi kept the baby's mother Shen from the ritual role of taking charge of the chieftain's funeral, the bondsmen knew that arranging the funeral was their own responsibility. They would put on two, both very large. In the first, Nuo Jiayou's soul was found on the mountain, placed in an effigy, fed medicine for its illnesses, purged of its evil, and sent off along the road on a beautifully adorned underworld horse. The chieftain's kin, assembled from the four corners of his domain and beyond, gathered around fire and coffin, ranked by their relation to his corpse: mother's brother, eldest daughter-in-law, younger daughters-in-law, eldest daughter, younger daughters, brother's daughter, junior agnates, wife's parents, wife's female cousins, father's sister, senior agnates, son's wife's parents, and friends and neighbors. Empty categories were filled by appropriate substitutes (daughters-in-law replaced by wives of the chieftain's cousin's sons, son's wife's parents by these son's parents, and so on). The order of categories and their spatial placement was indicated in diagrams appended to texts in Nasu script, recited at the funeral.Footnote 52

In the second funeral, held some years later, an ancestral body was fashioned: two figurines of green stone, one male and one female, placed in a wooden shell, the shell inserted into a red cloth bag, the bag inserted along with tiny iron implements for cooking and farming into an upright, hollowed section of peach log. Nuo Jiayou's name was written in Nasu script on a piece of silk and placed inside the peach log. A young agnate, perhaps the heir, perhaps a nephew, was assigned to carry the peach log up to a cliff cave where all the Nuo ancestral bodies were arranged on an altar in ranked order. That living agnate's name was written on another strip of silk wrapped around the peach log—demonstrating, as the linguist Ma Xueliang wrote while recording a version of this ceremony in the 1940s, “that the living will follow their ancestors.”Footnote 53

In these spatial and inscriptive diagrams, a world of kin was ordered around a body written as a string of bodies stretching into the ancient past. Descent was fashioned into lineage through inscriptive acts of settling souls into ancestral bodies, naming those bodies in writing, and linking them through writing to living bodies. Lining up ancestral bodies in order of descent while reading and rewriting their names was the way Nasu sorted out unilinear patrilineages, pruning branches and suturing gaps.Footnote 54 These rows of bodies were reinscribed as textual genealogies, stretching back in a single line to Ávì Áʋo, first chieftain of the tenth century, then back further as many as forty-six generations into the ancient past.Footnote 55 This was the structured skeleton of the native domain, the agnates holding down the domain's peripheral regions, the affines helping defeat the Qing state's episodic attempts to absorb the domain fully into regular administration. On this skeleton hung the tissues of bondage: the bondsmen of the chiefly house, the slaves of that house, the bonded tenants who filled its granaries.

Simply put, the bondsmen knew very well that kinship was made and shaped through writing projected onto a ritual plane. They knew no possibilities for any life independent of the chiefly house and linage. Taking them at their word, they were working to rescue the house and domain from annihilation with the most powerful means they had: extending the inscriptive activities of the funeral by writing descent and writing lineage, writing their entire world of action and experience back into being. The Qing legal system became a ritual system in this project, a formerly ordered public screen on which to project ritual writing. Qing legal writing was ideal for this purpose. Through the illegal, despised, ubiquitous, and indispensable institution of litigation masters (songshi), the activity of legal writing had been opened up to formerly silent classes of person: widows, farmers, and even, in very rare cases, slaves.

FINDING WRITING

The litigants in this case clearly had differential access to the skill of legal writing. The fourteen bondsmen were quick off the mark with their prompting plaint, having the resources of the chiefly house at their disposal, including its Chinese-language secretary. The chieftain Chang Shousi styled himself a gongsheng, implying that he had passed the prefectural examinations, and he wrote his own plaints. His opponents accused him of being an “illustrious and notorious litigation hooligan” (songgun) who had previously “piled up a mountain of cases on which the ink is not yet dry.”Footnote 56 The other parties were likely forced to search for litigation masters in the city after arriving to attend hearings. Though it was technically illegal for anyone other than a clerk or scrivener authorized by the yamen to write a plaint for someone incapable of writing his own, independent litigation masters wrote and submitted most legal plaints for pay, despite being subject to rhetorical attacks and legal persecution. Even the literate gentry often did not handle their own plaints, turning to litigation masters for their experience in the art of making concise and convincing arguments and their familiarity with the clerks of the yamen and its legal culture. “Habitual” litigation masters were to be found residing near the yamen in nearly any county or prefectural town, often in league with innkeepers and restaurant owners who offered hospitality to rural people.Footnote 57

Irritated by the plaints and counter plaints coming from the chiefly house, the departmental magistrate sent a runner to Mulian to convey the order that all parties must assemble in the prefectural capital for public interrogation. The bondsmen lifted their blockade of the Nuo sisters’ residence, and Lady An left for the city together with the three Ladies Nuo. Lady An brought along the six slaves. “They can give evidence as to the beating, insulting, and robbing” she reasoned.Footnote 58 The party journeyed over range after range of mountains, the women in litters carried by porters or slaves, the slaves walking. After a day of travel, they crossed Mulian's southern border. After another they reached the relatively flat southern basin in which the administrative city sat. Large numbers of Han immigrants had settled in this area after the Luɦo chieftain's reign had ended in 1567. On the third day, the party approached the city over the Huimin Bridge, surrounded by 30 mu of farmland owned by the Nuo lineage. This small outpost of the native domain supported artisans who produced work for the chieftain's household where they had easy access to imported materials.Footnote 59 Here, the travelers were held up by bondsmen and slaves belonging to the “rebel” party from Mulian and robbed of their traveling supplies and money.Footnote 60 “We fled separately from younger brothers’ wife,” the Nuo sisters said later. “The situation was indescribably savage.”Footnote 61

Unharmed, however, Lady An and the six slaves rushed through the massive north gate of the city. This gate faced the sprawling mountainous north of the prefecture, with its large non-Han population. All four gates to the city had names: the north gate had originally been named Profits of Virtue, but after a 1688 renovation it was renamed Soothing the Yi (fu yi).Footnote 62 The travelers hurried across the small city to the yamen of Hequ Department (zhou), a division that occupied the same position in the administrative hierarchy as a county (xian). Lady An demanded entrance at the yamen's front gate, but the gate porters turned her away, to her fury.Footnote 63 Some minutes or hours later, runners were dispatched to collect Lady An and the Nuo sisters and to take them to guest quarters in the yamen, with guards mounted at their doors.

County yamens throughout the empire were built to face south, with the presiding official seated facing south at the north end of the main hall during trials and other public events.Footnote 64 When this city was constructed in 1570, most of its yamens were built to face east like the Lv̩hu chieftains’ yamens, “so as not to vex the populace.”Footnote 65 In other respects, the yamen conformed to the architectural pattern of county yamens throughout the empire, designed to separate public administration from private concerns and to regulate the flows of persons and documents across this divide. The yamen was fronted by a great gate with five rooms for gate porters and other runners and a pavilion on either side. Just inside the gate was a jail and a shrine to the earth god. A second gate (yimen) led to another courtyard and the great hall, where the magistrate carried out public business, flanked by offices for registered clerks. The guest quarters were here, between this courtyard and a second hall, further within, where the magistrate and his private secretaries worked in private. Next to this hall was a large archive and library with eight rooms. Behind this was a large residential building with several floors.Footnote 66

After nine days, Lady An and the Nuo sisters endured public interrogation in the yamen's great hall. They spoke of Lady An's beating and humiliation, the rouge, clothing, and 2,300 liang of silver stolen from them, and the loads of silver they believed were being transported out of the realm. “The rebel slaves [meaning the fourteen bondsmen] have eaten my food, worn my clothing, and stolen my silver,” Lady An said. “They would not blink at killing me. Such savagery cannot be put into words!” Yet the women feared that they were not heard. They could not be sure of their translator, and they believed the magistrate was “hoodwinked by the rebel slaves’ marvelous tricks.”Footnote 67 Several weeks later, these four women, a group of village headmen, and the six domestic slaves all submitted written plaints on the same day,Footnote 68 followed closely by another group of village headmen and a group of bondsmen loyal to Lady An.Footnote 69 The women remained confined to their quarters in the yamen during this time, but the six slaves seem to have come and gone freely, relaying messages to all these people. Lady An and the Nuo sisters needed a litigation master to handle their plaints, and it was very likely Ah Han and his five enslaved companions who made contact, seizing this opportunity to create their own document.

The domestic slaves’ plaint was written in blunter language than those of the women, with fewer rhetorical flourishes. It was probably penned by a different litigation master, who helped them forge the confusing events that had followed their master's death into a plausible narrative. A flat denial of criminality would inevitably be contradicted by people of higher status and serve only to condemn them. So they worked out a way to narrate their temptation, their grave mistakes, their awakening to a fear of punishment, their flight into refuge, and their service to their mistress, lining up these elements like beads on a string. Their litigation master may have been cut-rate, but he was skilled enough to flesh out this sequence with blunt sentences on a single sheet of paper, to get the paper stamped by the clerk of the court, and to submit it to the proper office.

READING THE CITY

Writing about enslaved women in Bridgetown, Marisa Fuentes speaks of “reading along the bias grain.” “Like cutting fabric on the bias to create more elasticity,” she writes, “reading along the bias grain expands the legibility of these archival documents to accentuate the figures of enslaved women who are a spectral influence on the lives of white and black men and women.”Footnote 70 In one effort to make the archive more elastic, Fuentes follows an escaped slave through the streets. The young woman's flight, she writes, “maps the sensorial and architectural history in this urban site from an enslaved woman's perspective,” and redirects the historian's focus “to the sensorial perspective of the historically disempowered enslaved woman.” Though she does not put it this way, Fuentes is arguing that the city was legible to this longtime resident, whose perspectives on its streets were deepened by those streets’ histories of carceral architecture. Fuentes implies that this legibility was due to a coordination of “urban space, body space, and archive space” effected by power.Footnote 71

Imitating Fuentes’ strategy of spilling the archives’ contents out into the spaces in which they were created, I want to consider the conditions of legibility that made it possible for even enslaved and disempowered persons to attain a kind of spatial competency, even in a strange city.Footnote 72 I will argue that Ah Han's and his companions’ participation in legal writing opened up possibilities for reading: that is, for working out rough correlations across the dense bureaucratic spaces of the city, the domestic spaces of the chiefly house in which they had been raised, and the scriptural spaces of the funeral in which they had just participated. Reading is always a contingent synthesis of such planes or series, some enfleshed, others insubstantial.

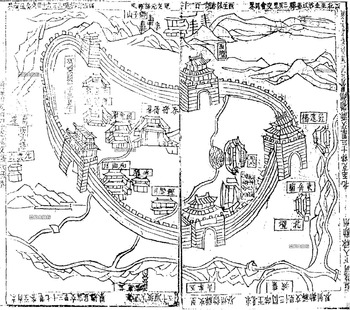

The slaves’ route through the city in search of litigation masters left no archival traces. But maps and descriptions in a 1689 gazetteer provide many clues (see Fig. 2). The city was small within its wall and had no suburbs without. Yet as the foremost administrative center in north-central Yunnan, it ambitiously attempted to contain within its cramped square kilometer the whole of imperial civilization, expressed in a pairing of state organs with institutions of literacy, and aspired to fold these into the hinterland beyond the north gate: “Soothing the Yi.” As the slaves emerged from the front gate of the departmental yamen, they would have faced the city wall, looming up against any morning sun. To their left was the warden's office (buting or limishu), headquarters for the Jinsha River frontier security officers, facing east, with a main hall in front and a residential building behind. A few steps along the wall was a branch office of the registry (jingli qiaoshu), also facing east, where a registrar managed documents for the prefectural magistrate. Behind, the entire southern half of the city was occupied by the yamens of the prefecture, their austere, columned fronts shutting out the dim sunlight from the east. The prefectural yamen sat in the city's southwestern corner, facing east, and built to the same plan as the departmental yamen but larger, with a great hall for hearings and trials and offices for the magistrate, assistant magistrate, judicial supervisor (tuiguan), the magistrate's private secretaries, and the registered clerks. A jail and a guesthouse sat just inside the front gate. A few steps away, the assistant prefectural magistrate had his own yamen, built on the same plan. The yamen of the army was also in this quarter, and the impressive yamen of the censoriate (yushitai) charged with monitoring and checking abuses of local officials. The imperial censor, who supervised a large circuit in Yunnan and Guizhou, was rarely resident, and the building was used as a branch of the prefectural yamen.Footnote 73

Figure 2. Wuding City, from a 1689 gazetteer. North is to the right. Source: Chen, [Kangxi] Wuding Fu zhi (1689, juan 1: 25a–25b).

Ah Han and the others had little reason to linger in this part of the city, packed with government compounds, the streets empty but for servants going to fetch water, buy food, or dispose of night soil for the large yamen staffs. Instead, they would have walked north, along the route they had come upon entering the city. Here the streets were lined with residences and shops framed with wooden posts and beams, with mud-brick or pounded-earth walls on the first story and wooden panels with window openings on the second. Seventy years before, the shops had names like First Prefectural Shop, Mountain-top Shop, and Neighborly Kindness Shop.Footnote 74 Near the north gate the slaves passed a pond built to center and contrast with the city wall's peripheral form: the built city was often referred to as chengchi, “wall and pond.” Around the pond were clustered the city's institutions of literacy and civil religion. On the west side was the Guandi Temple and the City God temple. These hosted both official ceremonies and popular cults: they were the only places where bureaucrats and commoners sometimes mixed.Footnote 75 On the north side was the Temple of Civil Culture (wen miao), which hosted the annual Confucian rites and provided support for the exam system. East of this was the Wuyang Charitable Academy, where sons of gentry prepared for the imperial exams.Footnote 76 The chieftain Nuo Jiayou had studied here for his shengyuan degree, and his father the chieftain Nuo Dehong had attended as a salaried licentiate. The open square between the bustling and colorful temples for Guandi and the City God on one side and the ascetic and dignified Academy and Temple of Civil Culture on the other was the place for markets, fairs, and theatrical performances. This plaza, where resident and itinerant people of all classes gathered, was the natural place for Ah Han and the others to begin their search for a litigation master. The City God was ruler of all the local dead and the focus of popular religion about ghosts and natural forces; the Temple of Civil Culture was the place for ritualized veneration of the written word.Footnote 77 This confluence was deeply familiar to the slaves as the center of all ritual practice in their home, in which the power of writing on which they were hoping to draw, was manifest.

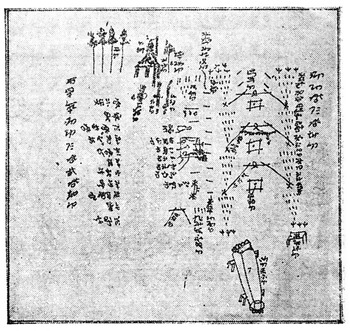

More than this, the entire city, if not recognizable, would have been legible, at least in fragments and perhaps, after a little walking, as a whole: “wall and pond.” Though they could not read or write, they knew what a spatial diagram was, and they had participated in the structures of legibility fashioned by writing, when a ritual space, like a house or a courtyard, was inscribed on paper and inscribed again on a ritual field. At Nuo Jiayou's funeral, they had hauled firewood and butchered animals while ritualists who could read and write Nasu built the ritual ground. This was a city with arbors as buildings, hosting a ranked gathering of ancestral beings and a crowd of their guardians and opponents. The central text recited there guided the dead person from the fire pit to the bedroom, the granary, the courtyard, the porch, and over the threshold, then along the road for the dead, winding through the arbors and altars of the ritual field. It diagrammed that field in drawings such as that in Figure 3, showing the coffin emerging from the ritual ground: a house with three gates, echoing the structure of the chiefly house and every yamen in the city.Footnote 78 Around the field are the seats for all the gathered spirit potentates: “a crowd of seventeen spirits, a crowd of fifteen female spirits, twelve fathers and mothers, heaven father and earth mother, sun father and moon mother … twenty-four seats for spirits, twelve seats for small spirits.…”Footnote 79

Figure 3. Diagram appended to central text recited at funeral ritual. Source: Ma, “Luowen zuoji xianyao gongsheng jing yizhu” (1987[1949]a: 203).

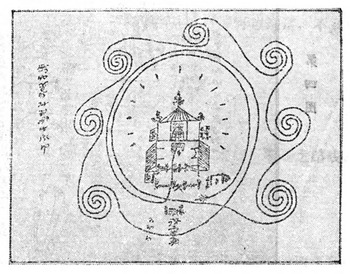

In another diagram (Fig. 4) the ritual city looks much like the map in the 1689 gazetteer of the administrative city. A line circles the ritual field, made of many pairs of branches inserted into the ground. One of each pair is bare, the other has leaves and bark. The branches form a path for participants to circle three times before entering the ritual ground. A ritualist who spoke to Ma Xueliang in 1942 diagnosed the paired branches as “text” (the leaved member of each pair) and “ghost” (the bare member), each pair containing an unspecified textual character and an unspecified spirit—modeling the form of writing.Footnote 80 This line parallels the line of text that rims the page on the city map: the textual interface between that diagram's internal geography and its outside. Within this periphery, the ritual field is shown as a fine, multistory building, resembling both the chiefly house and its analogues in the city, with a front gate, a courtyard, and an inner gate to the altar for the effigy of the dead, surrounded by seats for various participants, spirit and human.

Figure 4. Diagram appended to the central text recited at a funeral ritual. Source: Ma, “Luowen zuoji xianyao gongsheng jing yizhu” (1987[1949]a: 201).

To read these diagrams was to double them, to inscribe them into the earth as a variegated space legible to those who took their assigned places among all the other human and nonhuman participants. Each building/arbor expressed attributes of the beings who occupied it: bare oak branches for the “black arbor” (jȅ tʂ’ɛ̏), a prison for crimes and disasters, a leaved oak branch for the protector Gunɯ, who spread its feathered wings over the field.Footnote 81 The city too could be read thus easily enough: the closed yamen gates, the blocky warden's office, the lively site of the pond with its differentiated temples. In other words, the city's legibility was of the same order as that of the ritual field at Nuo Jiayou's two funerals, organized through writing, every arbor and spirit seat written and diagrammed on paper before being inscribed into the earth. Outer gate, courtyard, inner gate, first hall, third gate, second hall, archive—this arrangement was repeated with slight variations in each yamen and the academy and school temple. Every gate channeled and filtered persons and documents. Though they likely never passed the gates of any yamen but the one where their mistress was confined, the slaves knew this arrangement well. As the plan of the chiefly house, it partitioned and ordered every hour of their days. Their advantage as readers was that, as slaves, they had no assigned place. In the house they moved unremarked between the pigs near the outermost gate to the ancestors in the innermost hall; on the ritual field they traversed the places of various formal kin, unfree but mobile.

This was an architecture of power, where the capacity to shape others’ actions was fashioned by managing flows of persons and texts through the levels of these forms. Ah Han and his associates saw this arrangement repeatedly as Nasu ritualists used texts to inscribe power-laden spaces in ritual fields and shape the acts of human and nonhuman inhabitants. Writing folded space, layering it into visible and traversable zones on the one hand, and hidden and guarded zones on the other. Writing alone provided entrance to the hidden zones, where life and death were decided. The city's visible spaces—the closed, columned fronts of the yamens, the open, lively plaza around the pond—were easily read as the outward manifestations of this inner involution of text and space.

Though it was not unusual for widows like Lady An to submit legal plaints on their own behalf, it was extremely unusual for slaves to do so, not to mention so-called yi slaves who could not speak Chinese. I have been arguing that the six slaves’ focused intervention into the involuted spaces of writing in the city could only have been made on the grounds of a sophisticated understanding of what writing was and what it could do. The slaves’ experience with textual and diagrammatic inscription in funeral ritual had shown them that paper, ritual fields, and chiefly houses were parallel planes, traversed through acts of inscription. They knew that such writing layered built space into inner and outer zones: the traps of power. They could see how acts on one plane—making an offering, “smearing blood,” breaking through a window—might have effects on others. In this way, they knew what reading was: the coordination of points on different planes through distributed relays. The city was potentially legible to them, I have argued, because they knew about legibility and how to look for it. In this context, legibility was merely the awareness that the spaces they were traversing in order to get some writing done were inscribed across several planes, some already familiar.

CONCLUSION

This archive of legal plaints in Chinese was preserved in the Nuo chiefly house together with over five hundred manuscripts in Nasu script. Aware that our own readings should attend to the procedures of writing and reading that produce archival texts, I have approached these legal documents with an eye to the long and rich context of ritualized Nasu writing in this native domain. This has produced a sense of a thoroughgoing scripturation of the world rooted in Nasu textual practice and extended into the realm of legal writing in Chinese. Ritualized Nasu textual practice produced understandings of what writing was and what it could do that shaped the ways that litigants from Mulian domain participated in Qing legal practice. The participants in this legal case had doubtless attended many ritual occasions, especially funeral rituals, where Nasu texts were recited, copied, and inscribed into the earth in the form of arbors and spirit seats. As they authored plaints in Chinese, I have suggested, Nuo Jiayou's wife, affines, concubines, bondsmen, and slaves were projecting Nasu scriptural practice on to the ritualized screen of the Chinese legal system. In particular, I have tried to show how the bondsmen who used legal writing to promote a slave baby as chiefly heir were continuing procedures of making descent through writing in the form of ancestral bodies and in the form of script. The difference was that legal writing was more flexible than Nasu ritual writing, allowing participation from more kinds of persons, including enslaved persons. In this story, bondage was among the many forms of kinship framed by the walls and openings of the chiefly house—not, as in many conventional definitions, the condition of being cut off from kinship. To work to preserve that house was to struggle to reproduce the kinship of bondage. In addition, I have followed a group of domestic slaves as they came to participate in this project of making kin through legal writing. I have speculated that these slaves might have found, amidst their strange circumstances, echoes and resemblances of Nasu ritualized textual practice, which created opportunities for action and experience in the administrative city by making it partially legible. I hope this has opened up some broader possibilities for thinking about what literacy entails.

We left this case of chiefly succession with Lady An, the Nuo sisters, and their allies among the bondsmen and village headmen of the domain all employing people to furiously pen legal plaints. More testimony followed. Lady Tang fiercely disputed Lady An's charge that she had been having an adulterous affair with Qiu Maocai, the leader of the fourteen bondsmen.Footnote 82 The bondsmen attested to the very bad character of the chieftain Chang Shousi, whose father Chang Yingyun had lost his head to Qing military forces thirty years before.Footnote 83 Eventually, Lady An and her supporters realized that the claim to be nurturing the chieftain's heir gave Lady Tang and the fourteen bondsmen a crucial advantage. But there were more young enslaved women in the household. The baby Xianzong's mother, Ms. Shen, happened to have a sister, and this second Ms. Shen also had a baby. Lady An took this child under her protection as her husband's son. She named him Yaozong, implicitly admitting, by using a syllable of Xianzong's name, that the two children were brothers.

After two months, the magistrate rendered an opinion, as follows. The fourteen bondsmen had rebelled against their superiors and, worse, had been reluctant to beg forgiveness. Chang Shousi and the other affines had proven more amenable and subordinated themselves to good intentions. Though Lady An had listened to the incitements of others and made false accusations, Confucian principles dictated that as the chieftain's first wife she should be granted the care of the two orphans and raise them as her sons. Lady Tang and the babies’ two enslaved mothers should be set up in appropriate situations. Lady An would no longer listen to the provocations of others. The lineage leaders and all the bondsmen would assemble to jointly sign a statement to this effect.Footnote 84

The litigants met as ordered, but it did not go well. Though Lady An bristled at the magistrate's accusation that she had been incited to false accusations, she declared that she would nevertheless accept his compassionate order to raise the two orphans. The Nuo sisters and their three husbands agreed. Yet a senior lineage elder, Nuo Tingxiu, protested that he was not willing to accept the unexpected news that his cousin the chieftain had fathered two sons. Lady Tang argued that she should be the one to care for the two orphans and take charge of the Nuo lineage. The six village headmen who had presented plaints in the case brokered a compromise. Lady An could adopt the elder baby, Xianzong, who would inherit 60 percent of the domain, and Lady Tang could have the younger, Yaozong, who would inherit 40 percent. The village headmen commanded the bondsmen to return all the silver, clothing, deeds and contracts they had been safeguarding to Lady An. Seizing the moment, they also declared that the village districts they represented would henceforth pay their own taxes and no longer be subject to the Nuo lineage. The two Ms. Shens followed their babies to the separate residences of wife and concubine. No mention was made of the six domestic slaves who had intervened in the case.Footnote 85

All this was reported in detail by Lady An's brother An Deshun and a group of twelve bondsmen and regional village headmen. They appealed to the magistrate to command the lineage elders, as well as the eight regional village headmen not at the assembly, to accept this solution. The magistrate ordered the bondsmen to draw up a contract giving six parts of the domain to Xianzong and four to Yaozong and to send it to him to be signed, printed, and distributed. Taking note of the lineage elder Nuo Tingxiu's objections, the magistrate stripped him of any interest in the property. Finally—and this was his single significant judgment that was not simply an affirmation of decisions already made by the chiefly kin and bonded persons of the native domain—the magistrate granted the demand of the six village headmen to pay their own taxes.Footnote 86 In practice, this would mean that the land of a large area known as the “thirteen lower villages,” including arable land, forest, and wasteland, would no longer belong to the native chieftain. The bonded tenants would gain title to their land and the rights to buy and sell it. They would pay the relatively light land tax, but they would no longer pay rent to the chiefly house, supply young men for the chieftain's militia, or be subject to corvée obligations imposed by the chiefly house.

This was not the end of rewriting descent in Mulian, even in this generation. More than twenty years later, the chieftain Nuo Xianzong occupied his brother Nuo Yaozong's land and accused him of being fathered by a slave. Yaozong unsuccessfully sought legal relief at every level of imperial administration, finally traveling to Beijing to appeal the case. Tragically, the records of this case are not preserved in the Nuo family archive. But there are a few mentions in the court records of the Qianlong Emperor. In 1792, the Qing Minister of Defense commanded the Imperial Censor in Hunan to travel to Yunnan to resolve the case. After investigation, the Censor issued a memorial judging Yaozong to be the son of the slave Zhu Yifu and condemning him to military slavery in the northwest, where he doubtless lived only a short time longer.Footnote 87

Xianzong governed the native domain for four decades. He died in 1815, leaving a wife, three concubines, six daughters, eighteen bondsmen, and dozens of slaves, but no heir. Several months later, his wife Lady Sha filed the first in a long series of legal plaints.Footnote 88