INTRODUCTION

On 20 December 1844, three men, Tom Peters, William Mering, and John Sharp, swore before the Police Magistrate in Freetown, Sierra Leone, that they had recently been captured and sold into the transatlantic slave trade—for the second time in their lives. All three had previously lived in the British colony of Sierra Leone as “liberated Africans”— the Royal Navy had captured them from slave ships and registered them to serve apprenticeships on time-limited contracts, in accordance with anti-slave-trade treaties.Footnote 1 After apprenticeship, Peters and Mering had traveled outside the colony, southwards to Sherbro and the Gallinas River, to work in the extensive canoe trade of the Upper Guinea Coast. Sharp had migrated eastwards, to work on a farm in Soamah, in the Mende country. But at an unspecified time, kidnappers and rulers had captured them: Peters was traded for ivory, Mering detained on the pretext of damaging property, and Sharp held as compensation for the crimes of an acquaintance, who “took” another man's wife.Footnote 2

By November 1844, Louis, a Spanish slave trader operating in the Sherbro region, had bought all three men and “plenty other slaves.” He dismissed their protests that they were “Her Majesty's subjects.” Louis flogged and chained them in barracoons, the holding facilities from which slave traders would embark the three men on canoes, and then ocean-going ships. Another subject of Sierra Leone, Elizabeth Eastman, had tried to help Tom Peters. Louis punished her by flogging her so severely that he allegedly caused the miscarriage of her pregnancy and possibly even killed her.Footnote 3 Unjust detention had morphed into sale to transatlantic traders and fatal violence. The prospect of redemption was fading fast.

Louis embarked Peters, Mering, Sharp, and 345 other captives on the Spanish ship Engañador. But early in the voyage a British ship captured the Engañador and brought it north to Freetown. The Anglo-Spanish Court of Mixed Commission then re-released the captives, again as “liberated Africans.” After the Governor of Sierra Leone received copies of the statements that the three men gave to the magistrate, he authorized a naval expedition to seek redress and “pledges” from local African chiefs against the future capture or re-enslavement of liberated Africans. When the three men had made their statements, they could not have foreseen British warships sailing southwards with such a mandate. But now, violence was on the horizon.

The chain linking Peters, Mering, and Sharp to British naval retaliation against the Sherbro chiefs illustrates a major problem regarding abolition: political authorities struggled to define how anti-slave-trade law should operate among polities. As in the case of these three men, the norms for legal regulation could quickly morph from defining jurisdiction to violent confrontation. What does their story tell us about the process of abolition? How did anti-slave-trade jurisdictions relate to sovereign jurisdiction, which in the nineteenth-century Atlantic world usually involved sovereigns applying either free soil or slave soil within territorial borders?Footnote 4 How and why did regulation shift from coercive violence to settled compromise, and vice versa?

From various perspectives, social theorists and historians have analyzed the relationship between law, coercion, and society in different ways. Analyses have assigned primacy to codes, institutions, social practices, or economic change (inter alia) in shaping legal regulation and enforcement, and in turn being shaped by them. For instance, Max Weber's modernity through rational decision-making, Pierre Bourdieu's “entire social universe,” and E. P. Thompson's typology of law as institution, personnel, ideology, and rule of law all envisaged law as constitutive of society. Law was a tool for social domination and reproduction because it facilitated elites’ consolidation of control. Judicial hierarchy, high qualifications for entry into the legal field, and the symbolic power to name aided this consolidation, but also provided opportunities for resistance movements and social change.Footnote 5

One major aim for these scholars was to explain how the state's unified jurisdiction developed out of competition to control resource extraction, fragmentary class interests, and sectional differences. Jurists’ symbolic capital reflected and created a worldview that ensured widespread consent to state jurisdiction.Footnote 6 Elites used violence to create jurisdiction, and subsequent enforcement was premised on police coercion, extrajudicial violence, and the changing nature (and level) of consent.

But in the case of Peters, Mering, and Sharp, violence was not the whole story. In addition to applying naval coercion, Lieutenant-Governor Fergusson demanded “redress,” which involved exchanging human and non-human property to re-establish order between Sierra Leone and the Sherbro chiefs. As with law's role in society, commodity exchanges were modes of establishing and sustaining social order. From Bronislaw Malinowski and Marcel Mauss onward, anthropologists have emphasized that commodity exchanges, including gifting and trade, only make sense within the “totality” of social relations.Footnote 7 Mauss influentially enumerated the gift's obligations of giving, receiving, and repaying. Gift exchange distributed wealth and honor.Footnote 8 As Marshall Sahlins demonstrated, Mauss envisaged the basis of social order not in the war of all against all, but rather in the exchange of everything with everybody.Footnote 9

Gifting and commodity exchange were not necessarily peaceful, however. As Annette Weiner has argued, elites have consolidated their position by determining which objects may enter circulation as gifts and/or trading goods.Footnote 10 Such consolidation has also involved competition between elites to give ever-grander gifts, earn increased honor, and thereby attain political ascendancy.Footnote 11 Exchange could precipitate violent conflict. For instance, in the 1820s, on the Upper Guinea Coast, the chiefs of Falaba allegedly discussed threatening the Limba with war to compel them to hand over goods that Falaba could use to repay a gift to another group, the Mandinka.Footnote 12

Like social theories of law, anthropological studies of gifting and exchange have focused on cases where a shared worldview was possible and desirable. Learning from social theorists of law and economic anthropologists, we find that value exchange was analogous to law: it made sense only within all social relations, it was amenable to elite consolidation of power and legitimacy, and it created and consolidated worldviews, including of the life-cycle, gender relations, maritime trade, and conflict resolution.

However, for anti-slave-trade jurisdiction, there was little prospect of a shared worldview to underpin legitimacy. Polities in West Africa and the Americas were reluctant signatories of abolition treaties and agreements that British imperial hegemony had foisted upon them. The treaties established new courts to adjudicate over captures of slave ships for most of the nineteenth century until the ending of the transatlantic routes in the 1860s. At the same time, British naval patrols meant that the breakdown into violent confrontation was never far away. Anti-slave-trade jurisdiction involved coercion in its origins and regulation, elite negotiation regarding local jurisdiction over territory and people, and value exchange—all without the premise of a shared worldview.

The mixed-commission treaty courts and vice-admiralty courts that adjudicated captures, extrajudicial actions to “liberate” African captives, and Law Officers’ advice in Britain regarding controversial seizures have been the subject of recent scholarship. Scholars have fruitfully analyzed developments in inter-polity law in the context of battles between Atlantic proslavery and antislavery ideologies. Others have focused on British antislavery imperialism, underpinned by ideological distinctions between “civilized” and “barbaric” polities, thereby contributing to a belief that abolition required substantial political and commercial control of sub-Saharan West Africa.Footnote 13 Some related legal controversies, such as Burón v. Denman, still inform the doctrine that acts of state are non-justiciable: sovereign acts committed abroad deemed necessary for pursuing foreign policy are not liable to court jurisdiction or to compensation claims by subjects of other states.Footnote 14

The approach here is complementary yet different: I see the courts as one factor in making anti-slave-trade jurisdiction and law. Other important factors included the actions of African and Brazilian political authorities, British diplomats and naval officers, and the liberated Africans. Studying this legal regime in comparative Atlantic perspective, from the primary base of British abolition (Sierra Leone) and the primary mid-century target (south-eastern Brazil) unearths common problems of defining and regulating jurisdiction. This approach helps us to rethink the relationship between jurisdiction and regulation, the interactions between British imperial agents and local political authorities, and the possibilities for liberated Africans in a world of competing political formations in the nineteenth century. Central to these problems were the overlapping patterns of explosive inter-polity violence and negotiated value exchange.

THE CASE FOR COMPARISON

The Upper Guinea and Brazilian coasts were part of a shared Atlantic world in the age of abolition. To try to end the transatlantic slave routes in the nineteenth century, Britain signed bilateral treaties with other slave-trading polities. These treaties authorized naval captures of slave ships in peacetime and stipulated that local governments should apprentice the recaptives as “liberated Africans.” The treaties were enforced by bilateral courts of mixed commission, staffed by one commissary judge and one commissioner of arbitration from each cosignatory. Branches of the court sat in Freetown and inside the territory of a cosignatory, such as Rio de Janeiro. Recaptured Africans, slave ship crews, naval crews, agents of law, and diplomats thus interacted with the mixed-commission courts on both coasts. But in the 1820s and 1830s, the navy struggled to adhere to treaty exemptions, such as lawful Portuguese slave-trading south of the equator. Moreover, the governments of polities that still permitted slave ownership, including Brazil, Cuba, and the United States, were reluctant to enforce anti-slave-trade law.Footnote 15

The Palmerston Act of 1839 (2 & 3 Vict., c. 73) attempted to resolve the problems of complexity and hesitant enforcement by authorizing naval captures of Portuguese ships and other slave ships south of the equator, adjudicated by vice-admiralty courts in British territories. The Aberdeen Act of 1845 (8 & 9 Vict., c. 122) applied similar rules to the Brazilian slave trade. The result of these Acts, as well as the treaties that preceded them, was that Sierra Leone received the largest number of liberated Africans between 1807 and the end of the transatlantic slave trade in 1867. Brazil was the principal target of British anti-slave-trade actions between 1839 and 1851 and subject to intensive pressure until 1864.Footnote 16 The Upper Guinea and Brazilian coasts, particularly in and around Freetown and Rio, were therefore sites of crucial anti-slave-trade legal regulation.

There were important differences between the two coastal regions in the nineteenth century. The economy of the Upper Guinea Coast revolved around caravan trade routes. Caravans brought cattle, cloth, and shea butter from inland polities to coastal polities to exchange for kola, salt, and rice.Footnote 17 In contrast, the economy of Rio was geared toward maritime trade, especially in importing captives and exporting slave-produced coffee and sugar. The surge in global demand for these commodities meant that the importation of captives to Brazil remained high in the 1830s and 1840s, despite a legislative attempt to outlaw the slave trade in 1831 (briefly enforced until 1837).

Relations between slaveowners and slaves were also different on each coast, although there was great variety in work conditions, mobility, kin incorporation, and routes to manumission. In Rio, slaveowners often hired out enslaved men, who sometimes earned wages. A customary right permitted them to save some of their earnings for self-purchase.Footnote 18 Enslaved women often worked in domestic service. On the Upper Guinea Coast, the supply of captives through warfare or judicial punishment intensified to satisfy markets in the Americas. When that demand slowed after 1807, captors reassigned captives to work on rice plantations.Footnote 19 Although Sierra Leone was a “province of freedom,” it was surrounded by societies which had increased their use of slave labor in the nineteenth century. Within these differences in economies and enslavement practices, both coasts underwent an expansion in slave-ownership for commodity production between 1807 and 1839.

In jurisdictional terms, the similarities between the coasts were more important than their differences. They shared not only the anti-slave-trade legal patchwork but also sociopolitical practices that limited British diplomacy. On the Upper Guinea Coast, British officials were required to act within the constraints imposed by African chiefs. One common institution was the “Poro,” a society for initiates that connected gods, spirits, and the living, advised chiefly political authority, dispensed justice, and regulated trade and conflict.Footnote 20 The institution could also declare a “Poro,” forbidding white travelers and other outsiders from entering certain regions.

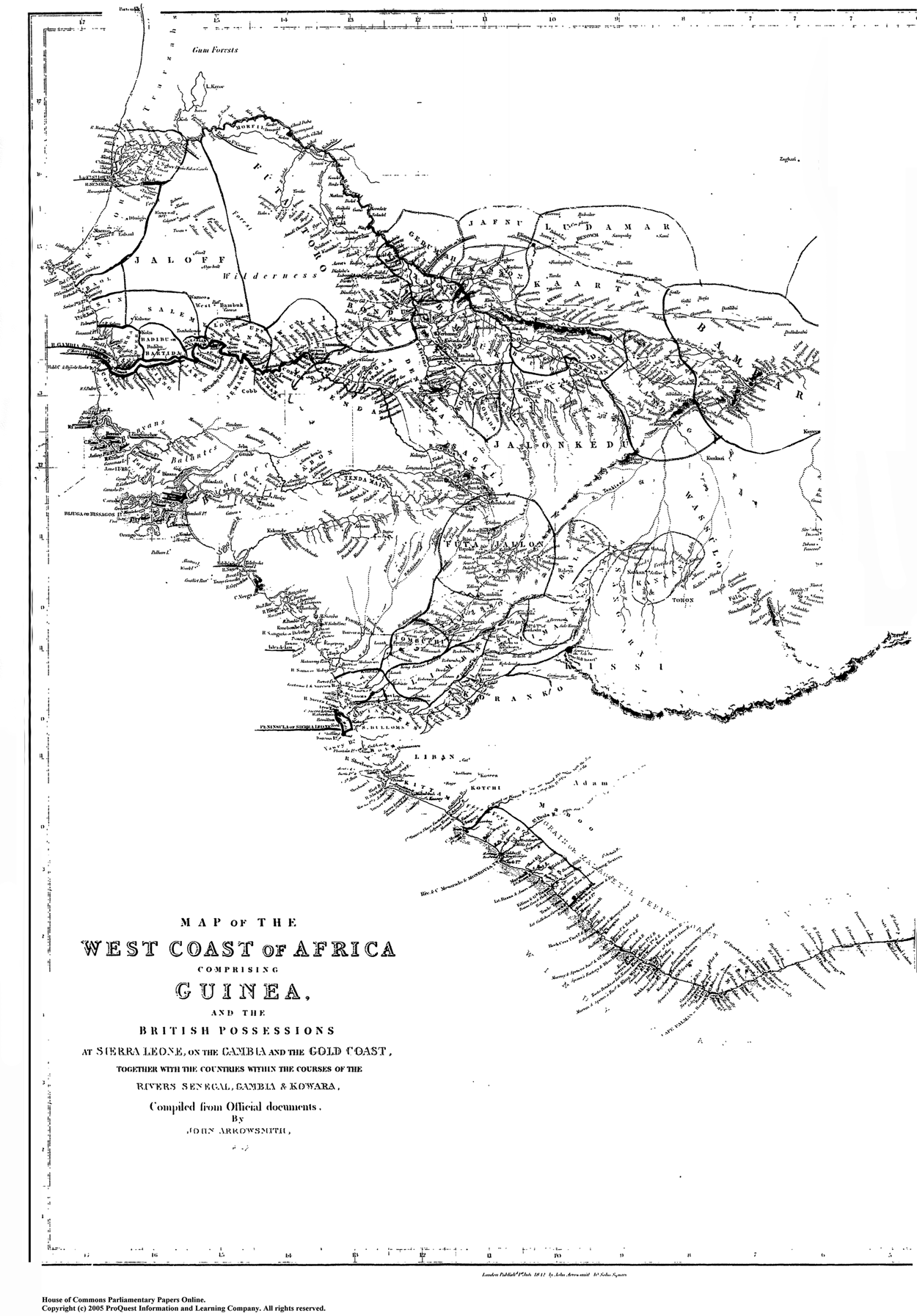

In 1836, the traveler F. Harrison Rankin noted that the Temne had declared a “Poro” forbidding outsiders from venturing further east than Magbelly on the Rokel river, on pain of capital punishment.Footnote 21 This prohibitory practice meant that African rulers considered Britain's colonial officers in Freetown irrelevant to their own affairs. Rankin recounted that the ruling Caulkers of Sherbro (descendants from the seventeenth-century marriage of a Sherbro princess to a Royal African Company agent) had recently organized a military expedition several miles north. The force razed the town of Rokel (opposite Magbelly) to the ground, with “the greater part of its people captured and sold as slaves.”Footnote 22 The force had bypassed the colony's modest borders with ease (see Map 1).

Map 1: “The West Coast of Africa Comprising Guinea and the British Possessions….” The Sierra Leone Colony is outlined in bold, on the coast in the center of the map with its name underlined. Report from the Select Committee on the West Coast of Africa; together with the minutes of evidence, appendix, and index. Part II—Appendix and Index (1842), paper 551, map follows p. 520. Source: Image from ProQuest's House of Commons Parliamentary Papers displayed with permission of ProQuest LLC.

In Rio, the sociopolitical limitations on British monitoring were less severe, but still unsettling. In April 1839, the court of mixed commission was due to adjudicate the capture of the Brazilian ship Ganges, captured with 419 Africans on board. However, soon after the trial began, a mob helped the captain of the Ganges escape by pelting the court's marshals with stones. Several hundred people surrounded the courthouse and interrupted the trial.Footnote 23 The chief of police, Eusébio de Queirós, managed to quell the mob, but on 7 May, three men attacked two British sailors who were part of the naval patrol stationed at Rio.Footnote 24

On both coasts, courts reclassified captives as liberated Africans in regions which resisted British imperial encroachment and where slave-ownership was still the norm. The reclassification processes, local elites’ defense of their polity's jurisdiction, and the limitations to British diplomacy, created similar problems regarding anti-slave-trade law on the Upper Guinea and Brazilian coasts, illuminating more general patterns in the Atlantic world.

JURISDICTIONAL CHALLENGES: THE COURTS OF MIXED COMMISSION

The main source of jurisdictional tension regarding anti-slave-trade law was the legality of captures. The commissary judges’ principal source of law for deciding cases was the particular convention between the two contracting parties. They also referred to ad hoc modifications sent by their respective governments; no guides or handbooks were published to assist them in their interpretative work.Footnote 25 Determining legality required deciding whether the capture occurred within the geographical limits stipulated by treaties. The difficulties posed by geography were apparent from the beginning, as demonstrated by the captures of the Brazilian slavers Activo and Perpetuo Defensor, adjudicated at Freetown in 1826. The applicable treaty, adapted by newly independent Brazil from the 1815 treaty between Britain and Portugal, limited naval captures to the high seas north of the equator.Footnote 26 Both ships had embarked captives north of the equator, yet had been captured south of it. The mixed-commission court restored both ships to their respective owners and awarded damages to them conditional on the approval of the Brazilian and British governments.

During the adjudication process, the recaptured Africans were left aboard each slave ship, under quarantine. They revolted and seized boats to escape to the mainland, effectively ending the crews’ prospects of reclaiming them as cargo for the restored ships. The court thus referred the verdicts to the Law Officers in London to determine what precisely was compensable: the death of recaptives during adjudication, the demurrage incurred by the ship, the overall loss of captives through revolt and consequent liberation, or nothing at all. Although the Law Officers struggled to provide a full answer, in both cases, they authorized the colonial government of Sierra Leone to treat the captives as liberated Africans. This authorization was not equivalent to precedent, but judges did not return captives to restored ships after the infamous Maria da Gloria case in 1833–1834. In that case, 208 of 432 captives (48 percent) died and many were left debilitated after the court in Rio decided it did not have jurisdiction over a Portuguese ship. The captors then sent the ship to Freetown, where the court restored the ship to its owner, allowing a third middle passage to Bahia.

Besides geography and compensation for fugitive recaptives, jurisdictional tensions arose over the nationality of ships.Footnote 27 In January 1839, the court of mixed commission in Rio de Janeiro condemned the Diligente as a Brazilian slave ship, despite its registered owner being Portuguese. The British Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, had argued that the mixed-commission court's jurisdiction should extend to include Portuguese ships because Portugal had refused to renew its anti-slave-trade treaty with Britain. But given that Brazil had been an independent state since 1822 and Brazilian and British judges staffed the mixed-commission court, there was no guarantee that the court would decide to adjudicate the capture as a “Brazilian” ship.Footnote 28

The behavior of the Diligente's owner and captain reveals how slave traders tried to avoid detection, capture, and adjudication. A Portuguese resident in Rio, Joaquim Pedro de Freitas, had bought the Diligente in Angola in August 1837. In July 1838, he arranged a passport from the Governor of Angola for the ship to sail to Mozambique with a passenger list of “colonists.” But Pedro de Freitas also instructed the captain to go to Rio de Janeiro or Montevideo “in case of extreme necessity.” The Electra captured the Diligente on 1 October, unsurprisingly on a path toward Rio.Footnote 29

The commissary judges found the claim that the passengers were “colonists” for Mozambique “specious.” One case report, written in Portuguese and sent to Brazil's Minister of Foreign Affairs, said that the “title of colonists cannot deserve the least credit,” and cited the branding on the Africans’ bodies as proof of the intention to sell them in Brazil.Footnote 30 The judges declared the capture lawful, arguing that they were following Palmerston's instructions to avoid a repeat of the Maria da Gloria case. That said, they disagreed about whether the sentence should be binding: the Brazilian judge insisted that the court permit Pedro de Freitas to lodge an embargo (appeal).Footnote 31 The British judge countered that no such domestic appeal applied to the court, a point the Brazilian Minister of Foreign Affairs ultimately conceded.Footnote 32 Tellingly, however, even the Brazilian judge did not suggest that a successful appeal would involve re-enslaving and re-embarking the liberated Africans.

As one would expect, the court's decision angered Rio's slave traders. The Diligente's mate escaped from a local hospital and locals threatened to murder the captors’ proctor (the legal representative for claiming prize money).Footnote 33 Between the founding of the mixed-commission courts and the Palmerston Act in 1839, jurisdictional conflicts emerged through interactions between judges, local political elites, and British imperial authorities. Jurisdiction expanded regarding geography and nationality, and recaptives were not re-embarked in cases of unlawful capture. But the courts left open the questions of how their jurisdiction related to sovereign spaces, the legality of captures in territorial waters rather than on the high seas, and eventual compensation for unlawful captures.

COERCIVE INTERVENTION

After adjudication, liberated Africans lived and worked in areas near the courts. In Brazil and on the Upper Guinea Coast outside the Sierra Leone Colony, they were outside British jurisdiction. Although anti-slave-trade treaties specified certain conditions for liberated Africans during apprenticeship, they did not stipulate how to regulate these conditions. Nor did the treaties attribute to liberated Africans status as local subjects or citizens. For African and Brazilian political elites, liberated Africans were often an extraneous inconvenience. The lack of enforcement mechanisms thus raised the crucial question of what responsibilities nearby British agents such as colonial administrators, naval officers, and diplomats had toward liberated Africans. This was precisely the problem that Tom Peters, William Mering, and John Sharp raised in 1844 in their testimony about Louis's slave-trading activities in Sherbro and the capture of the Engañador.

When the Lieutenant-Governor of Sierra Leone, William Fergusson, received copies of the testimony, he calculated that Louis had mistreated the three men inside the jurisdiction of Harry Tucker, chief of Little Boom River. Fergusson exemplified how “men-on-the-spot” forged careers out of anti-slave-trade activity: born mixed-race in Jamaica in the 1790s, he had won promotion to the rank of staff surgeon in the Royal African Colonial Corps in 1825. He worked as a civilian surgeon for the Liberated African Department with responsibility for the health of newly arrived liberated Africans in the 1820s, and was commissioned as lieutenant-governor in 1841.Footnote 34 Fergusson applied the same combination of anti-slave-trade zeal, practical knowledge (or undimmed self-confidence) in how to negotiate with chiefs, and willingness to use military force when communicating with Chief Tucker.

Fergusson decided that Tucker's response to his demands for explanations and redress were insufficient. On 20 January 1845, he wrote to naval Commodore William Jones, explaining that the three men were enslaved while pursuing an “innocent and lawful calling,” and that Louis had willfully ignored their protests.Footnote 35 “The legitimate trade of this neighborhood, and the personal safety of Her Majesty's subjects, are in a state of constant jeopardy by those very outrageous and illegal practices,” he wrote, and authorized Jones to intervene violently against the chiefs.Footnote 36

Fergusson and Jones's actions only make sense in the context of slaving on the Upper Guinea Coast from the eighteenth century onwards. As Walter Rodney and Paul Lovejoy have demonstrated, the abolition of the maritime slave trade led to a glut of captives along the trade routes of the Upper Guinea Coast.Footnote 37 As the market for sale to Europeans on the coast contracted, slave traders among the Fula, Susu, and Mandinka found other uses for the people they had captured or bought.Footnote 38 In particular, they enslaved the captives to cultivate rice on plantations and housed them in towns separated from the free population, called runde in Fula.Footnote 39

These changes in slave-holding brought changes in modes of resistance. As Ismail Rashid has argued, rebellions by captives were rejections of plantation labor and the ideological justifications for enslavement. Rashid cites two key cases to demonstrate changing modes of resistance. First, in 1785, those enslaved by the Mandinka had allied with Susu warriors, who were fighting their masters, and together they took over the town of Yangakori. The town became a “counter to the runde.”Footnote 40 It took the Mandinka ten years to recapture the town and destroy the fugitive settlement.Footnote 41 Second, in 1838, the slave Bilali, the son of an enslaved woman and a Susu king, led a rebellion after the king's heirs reneged on a promise to manumit him. He successfully established an independent settlement among the Limba, at Laminyah, that became a refuge for fugitives until 1870.Footnote 42

British imperial agents based in Sierra Leone, such as Fergusson and Jones, were thus acting with an anti-slave-trade mandate at a time of rapid change in slaving and slave resistance on the Upper Guinea Coast. These changes generated contradictory impulses for British agents. On one hand, Sierra Leone was often dependent on rice cultivated by slaves in other polities as a major source of subsistence, and so British agents were reluctant to start conflicts with African polities.Footnote 43 On the other, the rapid changes made visible several instances of slave-holding of dubious legitimacy, whether on the terms of African polities’ jurisdiction or of anti-slave-trade treaties’ regulations regarding liberated Africans.

In fact, Jones's intervention was not the first major British extrajudicial action on the Upper Guinea Coast. Retracing the pattern reveals the contradiction between extending British responsibilities to liberated Africans and limiting those responsibilities to respect the jurisdiction of African chiefs. In November 1838, Lieutenant Arthur Kellet landed on the island of Bolama. Portugal claimed imperial sovereignty over Bolama, exercised through the governor of Bissão, which was opposite the island. In the 1830s, Governor Caetano Nozolini used the island as a holding pen for slaves employed in porterage and agricultural commerce with the mainland. He also used it to accommodate slaves for sale into the transatlantic trade.Footnote 44 However, Britain also claimed sovereignty over Bolama, having allegedly agreed to its cession from the Bissagos—the local residents—as part of an ill-fated colonization scheme in 1792. The British revived their claim in a treaty with the kings of Bolama and “Biafres” in 1827.Footnote 45 Consequently, in 1838, Kellet symbolically removed Portugal's flag, replaced it with Britain's, and transferred 206 slaves to HMS Brisk to be freed by the vice-admiralty court at Freetown.

Kellet's actions exposed the contradiction between Britain's claim to sovereignty over Bolama and the free soil principle that operated inside British colonies. The Slave Trade Act 1824 (5 Geo. IV c. 113 §22) authorized judicial adjudication of prize slaves as prizes of war for “the Purpose only of divesting and barring all other Property, Right, Title, or Interest whatever [regarding them].”Footnote 46 A judicial verdict that a capture was lawful removed all property rights from the captives, thereby creating a legal tabula rasa. However, Chief Justice Robert Rankin, judge of the Vice-Admiralty Court, pointed out that if Bolama was under British sovereignty by treaty before Kellet's actions, any slave who set foot there became free by common law through the free soil principle. A judge had no authority to adapt or add to that freedom through the application of a parliamentary statute. There could be no rights, title, or interest to remove, and so the court had no authority to declare the “slaves” free.

Kellet fretted about his diminishing prospects of prize money, and Governor Richard Doherty worried about how to manage a population that now existed in a legally ambiguous zone. The extant official documents focused on prize money, occluding what happened to the recaptives. The Liberated African Department probably sent them to Freetown or its surrounding villages as apprentices, applying the same methods as with restored slave ships.Footnote 47 Kellet's violent action had freed more captives, but had further confused the boundaries between anti-slave-trade jurisdiction, British imperial claims to jurisdiction, and African and Portuguese sovereign authorities.

Two years later, in the late rainy season of 1840, Captain Joseph Denman raided Spanish slave traders at Gallinas, south of Sherbro.Footnote 48 Denman's mission aimed to resolve two cases. First, King Siaka of Gendema had protested against the navy's blockade of the Gallinas ports, which prevented the chiefs from trading for subsistence grains with Sherbro and the Plantain Islands. In a letter to Doherty, signed by Siaka and the powerful Rogers family but possibly drafted by Spanish slave traders, the rulers stated that “although we are Africans,” the “law of Nations” still applied: it was unlawful for the British navy to blockade a foreign port in peacetime.Footnote 49

Second, in September 1840, a liberated African woman from Sierra Leone, Fry Norman, was detained in Gendema.Footnote 50 Norman was a washerwoman who had tracked her employer, a Mr. Lewis, to the Gallinas for repayment of a debt. Unfortunately for Norman, her former hirer during her apprenticeship owed money to King Siaka's son, Prince Manna, who detained Norman as security.Footnote 51 There was an elision between Norman as liberated African, debt pawn, captive, independent creditor, and incorporated member of her former hirer's kin.

Since liberated Africans in Sierra Leone were not attributed British subjecthood until 1853, the governor had no formal obligation to negotiate Norman's release. But in October, Governor Doherty ordered Denman to rescue Norman, using force if necessary. Denman negotiated the rescue, burned the barracoons of a Spanish slave trader, and liberated 841 slaves in Freetown. He also negotiated—or rather, extracted—anti-slave-trade treaties with Siaka and Manna, even though neither Doherty nor the Foreign Office had authorized him to do so.Footnote 52 The resolution of Norman's complex and vulnerable status was re-entry into Sierra Leone and the use of coercion to extend anti-slave-trade treaty law.

In light of Kellet and Denman's actions, the case of Peters, Mering, and Sharp from 1845 followed a pattern of intervention. Commodore Jones went to Gallinas to demand redress and promises from local chiefs about the future good treatment of liberated Africans. On 4 February, Jones entered Gallinas with 286 men and burned the barracoon of the slave trader “Angel Jimenes [sic],” who had admitted to branding Peters before putting him on the slave ship Engañador. Jones ordered the destruction of the towns Tindes, Taillah, and Minah to teach the ruling Rogers family a lesson.Footnote 53 Three locals were killed and fourteen wounded. Over the next three weeks, Jones negotiated with, cajoled, and threatened the Gallinas chiefs until they made reparations and pledges, in an extended, multifaceted debate about British imperial and African understandings of anti-slave-trade law.

Initially, the African chiefs denied that the anti-slave-trade treaties they had signed with Denman in 1840 obliged them to expel all Spanish slave traders from their territories. They even claimed that Denman had compelled them to sign the treaties at gunpoint, thereby voiding them.Footnote 54 Next, Jones and the chiefs disagreed about the boundaries between, and mutual intelligibility of, British and chiefly jurisdiction. Regarding the punishment of Elizabeth Eastman, who had tried to save Tom Peters from the slave traders, Chief Harry Tucker insisted that the flogging was sanctioned by the “country laws” which applied to all residents of his chiefdom.Footnote 55 Prince Manna, accused by Mering of selling him as a slave, asked Jones for what he described as a “jury” trial, namely that Mering accuse him in person in Gendema.Footnote 56 Finally, Jones and the chiefs disagreed over the process of redress. When the chiefs asked if they should seek payment from the Spanish slave traders to pay compensation to Jones, the commodore refused. The Lord Commissioners of the Admiralty had previously demanded an explanation from Denman for a similar strategy, perhaps because it had involved the transfer of goods from a slave trader to the chiefs, and therefore exposed the navy to an accusation of perpetuating the commercial relationships of the transatlantic slave trade. Extrajudicial violence, the normativity of treaties, mutual respect for municipal (internal) jurisdictions, and the use of goods to compensate unlawful detention informed how African and British authorities determined anti-slave-trade jurisdiction in the 1840s.

On 24 February, the chiefs refused to sign a new treaty, but agreed in principle to pay compensation. Jones spared Gendema from being razed to the ground to remind the chiefs that they had something to lose. A compensation payment of ten slaves, half of the value paid in muskets, powder, a cutlass, tobacco, and cloth, was unacceptable because the British government “cannot regard human beings as the subject or the representation of pecuniary value; as such, therefore, those goods and those five persons cannot be received.”Footnote 57

By June, Harry Tucker had paid compensation to Eastman (subject to the approval of the Navy and governor), who in fact had survived her ordeal, in the form of iron bars, cloth, and the liberation of five slaves who were sent to Freetown.Footnote 58 Instigated by liberated Africans’ testimony, naval violence against riverine chiefs had produced compensation in the shape of more freed slaves. But the price was intensified legal conflict between the colony and neighboring chiefs over the responsibilities, jurisdiction, and enforceability of anti-slave-trade law.

In one sense, Jones's coercive actions seemed more severe than Kellet's in Bolama or Denman's in Gallinas: he destroyed towns rather than flags or barracoons and used a larger number of men to do so. But in another sense, Jones's use of violence was primarily a theatrical show of force and did not result in the mass removal from African rulers of slaves detained for maritime trading or for domestic servitude. Tucker's compensation was, after all, paid through negotiation rather than seizure or confiscation.

Jones's actions also revealed the limits of British imperial authority and ambition on the Upper Guinea Coast at mid-century. The Navy had the power required for performative incursions and burnings, but not for occupation, colonization, or even sustained dialogue. These performances mattered because there was no guarantee that Portuguese and African political authorities would recognize Britain's claims to sovereignty in Bolama or Sierra Leone.Footnote 59 Britain's forces received a timely reminder that such recognition was never self-evident in May 1855, when a military and naval expedition went to Malaghea on the Mellacori River. The expedition of 150 men sought compensation for damage to the property of French and British traders from the king of Malaghea, Bamba Mina Lahai, and the chiefs of the Mooriah country. It ended in disaster.Footnote 60 Although the troops burned most of the town, thirty men drowned and a further thirty-two were killed, missing, or taken prisoner. The expedition also violated the king's flag of truce.Footnote 61 The governor, Robert Dougan, was required to abandon the claim to compensation in exchange for the return of prisoners and the opening of roads and rivers to British and French traders in a peace treaty with the king. Ultimately, Dougan was dismissed from office.

Britain continued to defend the claim to sovereignty over Bolama until the United States decided an arbitration case in favor of Portugal in 1870. Notably, then, British projections of expanding anti-slave-trade law by force were primarily calculated at disrupting other European imperial and slave traders’ enclavist, riverine, and archipelagic systems rather than at colonizing or increasing imperial influence over African chiefs. The regime was only subject to the authority of the Law Officers or Lord Commissioners of the Admiralty in ex post facto fashion—Jones sought approval from the Commissioners on 18 February, fully two months after Peters, Mering, and Sharp testified to the police magistrate.Footnote 62

As on the Upper Guinea Coast, the presence of liberated Africans in Brazil created a problem regarding British and Brazilian responsibilities for liberated Africans under anti-slave-trade law. British intervention in Brazil was not as spectacularly violent as on the Upper Guinea Coast, but it was similarly coercive. By 1845, the mixed-commission court in Rio had processed 4,785 liberated Africans, creating paper trails regarding their identification and apprenticeship.Footnote 63 But that year, Brazil refused to sign another anti-slave-trade treaty to extend the court's jurisdiction beyond its initial fifteen-year term.Footnote 64

In the years before the court's closure, the judges had tried to hold Brazilian authorities accountable for the treatment of apprenticed liberated Africans. The Anglo-Brazilian treaty did not specify sanctions against either party for abusing liberated Africans, and so the only option for judges was to notify British diplomats who might then exert pressure on the Brazilian government. For example, in November 1843, the British commissioner alleged that administrators treated apprentices with “cruelty” inside the Casa de Correção, the first modern prison in Brazilian history. Such complaints were nothing new: Casa workers and convicts had famously petitioned the Emperor himself regarding their dismal work conditions in 1841.Footnote 65 However, by the time the Foreign Office raised the allegation with Brazil, the court was due to close, which allowed officials to delay responding to it.Footnote 66

Brazilian officials responded in October 1845. The Casa's administrator of public works, Thomé Joaquim Torres, wrote to the Minister of Justice flatly denying that the liberated Africans had suffered in terms of diet, illness, or overwork. Probably in full knowledge that there was no mixed-commission court to verify his report, he generously mentioned that “this Casa, and all its accommodation, are open to anybody who might like to visit them.”Footnote 67 Indeed, “the Africans have demonstrated great enjoyment in the occupations to which they have been assigned,” both inside the Casa and working for private hirers.

Torres also enclosed two tables as proof. The first described the daily diet of the liberated Africans: dried meat, beans, farinha, rice, and bacon.Footnote 68 The second laid out the occupations of the liberated Africans, including stonemasonry, construction, carpentry, and blacksmithing. Professed transparency and schematic tables were scripted responses to complaints about the Casa.

British officials had no way of verifying Torres's report. The principal channel for gathering information, the British judge on the mixed-commission court, no longer existed. As an alternative way to sustain pressure on Brazil to end the slave trade, parliament passed the Aberdeen Act in August 1845, to continue naval captures. The Act increased distrust in Brazil regarding British actions and motives. By replacing the mediating effect of the mixed commission with aggressive unilateral action, British politicians uprooted the assumption that abolition was based on consent (even if that consent was often a façade). The only option now available to British politicians for monitoring liberated Africans was to use local diplomats in Rio.

In 1849, having realized that some apprenticeships had expired, the British chargé d'affaires in Brazil, James Hudson, ordered Robert Hesketh, the consul at Rio, to compile a report on all the liberated Africans he could trace there. Hudson hoped to use the report to agree on a protocol with the Brazilian government to sanction shipments of liberated Africans to a British colony or to Liberia (as a neutral alternative). It took Hesketh over two years to compile the data on 856 liberated Africans who had been apprenticed after liberation by the mixed-commission court. He listed their occupations and workplaces and commented on their lives or work conditions. The protocol ultimately failed, but Hesketh's survey became a focal point for liberated African protest.Footnote 69

In August 1850, perhaps aware that Hesketh was interviewing their fellow apprentices, several liberated Africans in the Casa wrote to him begging him to facilitate their release. They complained of their “disgrace” at having served nineteen years as apprentices rather than the stipulated fourteen.Footnote 70 In November, they wrote again, raising the tempo:

To Mr Consul

The most worthy Excellency, we implore you that we might hope to lay at the feet of Your Excellency to know the second decision of Your Excellency and because in the hand of Your Excellency we hope to reach some hope, that we are disregarded and therefore we seek and ask Your Excellency to send us with all certainty to Your Excellency to know well we are slaves until death in this House of Correction if like this we wish to know we bless the hand of Your Excellency as father of humanity.

The Africans of the House of Correction

23 of November 1850.Footnote 71

The letter-cum-petition emphasizes the uncertain status of the liberated Africans. They were out of sight—“disregarded”—yet knew that they were visible to British diplomats. They collectively realized that they had no way to hold the administrators of the Casa to account, but that the diplomats had the authority to criticize them. This lack of power but access to authority led to the double qualification: “we hope to reach some hope.” The petitioners ended their address by praising Hesketh as fictive kin, as a “father” who represented “humanity.” This term translated their particular material and political objectives into an apparently moralistic register, above the level of inter-imperial diplomacy, yet the authors hoped that those same diplomatic mechanisms would remedy their situation.Footnote 72 The Africans had combined a tradition of Casa protest with the language of moral obligation and their unusual inter-polity leverage.

Hesketh's survey and the Casa petition were potentially explosive. Like Peters, Mering, and Sharp's testimony at Freetown, the liberated Africans complained about captivity and abuse, drawing local British diplomatic attention to their plight. But unlike that case, there was no direct coercive response and Hesketh quietly filed the petition inside his handwritten survey, to be classified as a miscellaneous extra in the consulate's archive. Why did the petition elicit so little attention?

Ten months previously, in January 1850, the British vessel Cormorant had captured the slaver Santa Cruz inside Brazilian waters, at São Sebastião, after it had disembarked approximately seven hundred captives on the coast.Footnote 73 The commanding admiral, Reynolds, had ordered the Cormorant's captain, Schomberg, to make no further captures within Brazilian waters lest he breach treaty and parliamentary law. However, the ubiquitous Hudson took a different view, wishing to use the case as a pressure point. Perhaps he was enraged by secret intelligence about the Santa Cruz's crew, who had suppressed a shipboard conspiracy to revolt by executing the ringleaders. Perhaps Hudson saw subsequent Brazilian parliamentary protests against the capture as a sign of weakness.Footnote 74 He notified Palmerston that the Brazilian government was prepared to start negotiating a new anti-slave-trade treaty, and encouraged him to replace cumbersome naval steamers with lighter Banshee vessels to increase the number of captures along the Brazilian coast.Footnote 75 Without the mixed-commission, Hudson envisaged naval patrols that were no longer limited to the high seas by treaty jurisdiction or diplomatic conventions.

Hudson's proposal arrived at an opportune time in Whitehall. By early 1850, an influential parliamentary select committee into the efficacy of naval suppression had been in full swing for almost two years. It regularly heard evidence about the failings of abolition policies. One naval surgeon's account from his time in Brazil in the 1840s had declared naval suppression of the Brazilian slave trade a failure.Footnote 76 William Hutt, the committee's chair and an opponent of naval suppression, proposed a parliamentary motion to withdraw from treaty arrangements that obligated Britain to maintain the naval squadrons. As Richard Huzzey has demonstrated, Lord John Russell's Whig government presented the issue as a vote of confidence in his administration.Footnote 77 The government won the vote by 232 votes to 154, but the strength of opposition threatened to undermine the naval squadrons.Footnote 78

Following the crucial vote, Russell was under pressure to consolidate parliamentary and public support for the naval squadrons. The earl of Minto, a former first lord of the admiralty and close political confidant (and who had the good fortune to be Russell's father-in-law), held meetings with celebrity naval aggressor Denman and a former naval officer turned Whig MP, Dudley Pelham. Minto confidentially reported that Denman and Pelham advocated extensive barracoon raids along the West African shoreline, and urged Russell to meet them.Footnote 79 The joint plan, based on Denman's charts of slave-trading locales on the West African coast, clearly aimed at suppressing the Brazilian slave trade by cutting off supply on the other side of the Atlantic. His collaborator, Pelham, rubbed his hands at the prospect of a preemptive strike to “defeat the attacks of the Huttites.”Footnote 80 Russell sanctioned British naval vessels to seize slave ships inside territorial waters. But there was a surprise: rather than targeting West Africa, he ordered naval seizures along the Brazilian coast (see Map 2).

Map 2: “Chart of the Coast of Brazil from Maranham [sic] to the River Plate” (J. Arrowsmith, 1850). The red dots indicate where slavers landed their cargoes and where others were fitted out for slave-trading. Source: The Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress.

On 22 April, in an explicit vindication of the Cormorant's capture of the Santa Cruz, the law officers advised the Admiralty that existing legislation contained “no Restrictions as to the limits within which the Search, Detention, and Capture of Slave Traders under the Brazilian flag, or without any Nationality, are to take place….”Footnote 81 Such advice ignored customary inter-polity law that decreed that waters up to three nautical miles from the coast were sovereign spaces. The Cormorant's aggression, Hudson's opportunism, and Russell's parliamentary one-upmanship combined to sanction naval violence.

Upon receiving the new instructions on 22 June, Admiral Reynolds ordered naval captures inside Brazilian waters and ports. Subsequent cases of controversial seizure, including by the Sharpshooter at Macaé and the Cormorant at Paranaguá, sparked violent resistance by locals. A municipal judge at Paranaguá labeled British actions “verdadeira pirataria” and a breach of “direito internacional.”Footnote 82 On 12 July, the Brazilian government resumed a debate, in secret, in the Câmara (lower chamber) on a bill that would strengthen criminal penalties against new importations of African captives. The amended bill became Lei 581 on 4 September.Footnote 83 Hudson reported Brazil's offer to negotiate a new treaty in exchange for revoking the naval instructions, but also advised the British government to maintain the pressure.Footnote 84 The navy captured the Amelia in late 1850 and transferred some recaptives to British colonies in the Caribbean.Footnote 85 Nonetheless, as Brazil's enforcement of its municipal anti-slave-trade law improved, the British diplomatic-naval nexus transformed from coastal aggressor to intelligence supplier to Brazil, until the closing of the Brazilian slave trade in 1856.

British priorities had thus shifted from protecting liberated Africans to violent coastal naval policing. The difference between the coercive response to the plight of Peters, Mering, and Sharp in Sherbro and the diplomatic indifference to the Casa petition in Rio came down to British agents’ increasing disillusionment with the Brazilian government and domestic political pressures rather than any perceived “civilizational” difference between the Brazilian and Upper Guinea Coast polities. Having failed to attract diplomatic assistance, the Casa Africans continued to work and reside there, often in deprived conditions, until 1864, when surviving liberated Africans were emancipated from apprenticeships in Brazil. The local discretionary power of British diplomats such as Hudson and naval crews such as the Cormorant's were thus central to explaining how and why abolition switched from diplomatic monitoring to naval violence. Crucially, for histories of the abolition of the Brazilian slave trade, it was not so much jurists’ symbolic capital that underpinned anti-slave-trade jurisdiction as the changing evidentiary primacy regarding where sovereign responsibility to combat illegal slave-trading lay: from apprenticeship work conditions to coastal slaving practices.

VALUE EXCHANGE

Coercive violence was one dimension of regulating anti-slave-trade law, but it was only ever possible in short bursts. Even as world hegemon, the British Empire did not have the personnel, firepower, epidemiological knowledge, or domestic support to launch full-scale invasions of the Brazilian and Upper Guinea Coasts. Imperial officers needed to resolve conflict in ways that satisfied both anti-slave-trade prerogatives and municipal jurisdictions. On the Upper Guinea Coast, conflict revolved around cases of liberated Africans held captive or re-enslaved: How did the Sierra Leone governor and African chiefs negotiate over them? In Brazil, who had authority to determine the legality of naval captures after the end of the mixed-commission court, especially in light of British seizures in Brazil's territorial waters in 1850?

On the Upper Guinea Coast, formal agreements between Sierra Leone's governor and African chiefs in the 1830s and 1840s provided only a partial resolution to re-enslavement. In 1837, Governor Henry Campbell signed a Convention with fifteen nearby chiefs to pay them annual stipends in return for commitments to keep roads open for trade, restrict Poro, and refer any potential conflict between chiefs to the governor. The chiefs were also obliged to return any liberated African “enticed away, kidnapped, purchased, or held for any debt, or pretended claim, and that no satisfaction shall be required” for the return.Footnote 86 The governor (or his appointed agent) was authorized to request the return. Similarly, the governor undertook to return any “domestics”—those enslaved within the chiefs’ jurisdictions for agricultural production rather than outside sale—who sought refuge in Freetown.Footnote 87

Other treaties between the Governor and chiefs farther from Sierra Leone committed the parties to abolishing the slave trade and treating the “lives and properties of liberated Africans [as] inviolate.”Footnote 88 Unlike the Convention, the treaties did not specify how to return re-enslaved liberated Africans to the Colony. These conventions and treaties differed from prevailing Upper Guinean norms of establishing relations between authorities. For instance, one norm developed through the caravan trade involved gift exchange at the end of negotiations to recognize chiefs’ respective authority, thereby combining politics and commerce. The convention and treaties seemed narrow and inflexible in comparison, and also like stepping-stones to European territorial annexation.

However, following the treaties from bounded text to situational practice reveals a very different pattern for resolving re-enslavement. Between 1845 and 1862, the governor wrote dozens of letters to African chiefs about liberated Africans who were re-enslaved or held captive in their jurisdictions. There were at least forty negotiations between the governor and chiefs, which resulted in the return of at least 120 liberated Africans or other British subjects in total.Footnote 89 To comply with Poro, Sierra Leone's black police constables traveled outside the colony, partly as diplomats and partly to rescue re-enslaved liberated Africans. They were crucial to the government for communicating with polities and developing diplomatic relations along the Upper Guinea Coast and inland.Footnote 90

When governors and chiefs negotiated over re-enslaved liberated Africans, they were engaged in performances of gifting. In a commodity economy, persons and things assume the social form of things. In a gift economy, things assume the form of persons.Footnote 91 For example, in Malaghea (the town where British naval forces were routed in 1855), the liberated African John McFoy suffered re-enslavement. During his thirty years of re-enslavement he had married and had five children. In January 1860 he managed to escape and travel to Freetown, where he asked the governor to request the freedom of his family, too. In March, the king and alimamy of Malaghea, Sanasee Famah, sent the children to Freetown. Afterward, the governor sent the king £10.Footnote 92 In other interactions, governors sent gifts that included baft fabric, rum, tobacco, arms, and cash. These exchanges were not commercial, because the parties were political authorities rather than merchants, acting to resolve problems regarding inter-polity mobility rather than negotiating over price. From the chiefs’ point of view, then, to send a re-enslaved liberated African to another political authority was to give a gift. It imposed an obligation on the governor to send a gift of equivalent value, thereby building diplomatic norms, respecting mutual jurisdictions, and consolidating commercial relationships. Such exchanges more closely resembled the political and commercial functions of caravans than the injunctions of officious treaties.

The local letter books, and cases like McFoy's, tell an important story for the period from 1839 until the late 1850s, one that complicates the conventional argument that British imperial antislavery was the first step toward European colonization in Africa.Footnote 93 Gifting is not necessarily an exchange between equals; it could be competitive, or overbearing, gradually reducing the chiefs’ honor over time. But in these cases, there are good reasons to emphasize reciprocity rather than domination. After all, if British officials wished to frame the interactions with the chiefs as imperial, they could have withheld gifts, or resorted to violence. And if the chiefs perceived the gifts to be inadequate, they could have retained the re-enslaved liberated African, or written a complaint to the governor. The chiefs, then, understood the performance of gifting as the purchase of freedom of a liberated African, a friendship between polities, and a mutual recognition of respective jurisdictions, but not as an extension of British extraterritorial, imperial jurisdiction.Footnote 94

In the 1860s, gifting, treaty-making, and annexation overlapped. In 1861, the Sierra Leone colony annexed Sherbro and Koya.Footnote 95 But even under formal treaty law, the return of liberated Africans could take the form of gifting. Indeed, the governor admitted that treaties alone were not sufficient to guarantee the return of British subjects, a status attributed to liberated Africans settled or resident in colonial Sierra Leone in 1853. In 1865, the Reverend J. H. Dufort asked the colonial administration to intercede with chiefs of independent polities in the Rio Pongo area who had signed a treaty with the governor. Dufort complained that a boy had been enslaved, yet the governor's secretary replied, “The colonial government cannot undertake to pay for the liberation of the boy… you should apply to the proper chief for the boy in question.” If the chief complied, the government could “perhaps reward him in some shape.” The secretary did not suggest violent intervention was an alternative. In fact, the boy would have to take the initiative and “make his escape on board some British vessel where he would receive protection.”Footnote 96

Anti-slave-trade law involved coercive intervention and value exchange as interchanging processes. Since a comprehensive, shared worldview could not be derived from the treaties, value exchanges via local agents were a crucial source of law: they represented and reinforced respective jurisdictions, consolidated relations between elites, and protected liberated African status.

As well as shaping relations between the Sierra Leone colony and the chiefs of the Upper Guinea Coast, equating the “value” of a liberated African with material or financial assets shaped ongoing relations between Britain and Brazil. In 1858, the British and Brazilian governments established a mixed commission to evaluate various compensation claims. Brazilian subjects made ninety-eight claims to compensation for the allegedly unlawful captures of slave ships by Britain's navy. British subjects made fifty-two claims regarding the costs and loss of property incurred due to rebellions, insurrections, and port blockades in Brazil. The commission struggled to reach a verdict in various rounds of correspondence. British and Brazilian commissioners conflicted over whether they had the authority to review captures adjudicated at the Rio and Freetown mixed commissions for compensation claims, how to assess the value of each claim, and a reasonable rate of interest. The commission was suspended in 1860.

After the commission fell apart, the two governments tried to find agreement on estimates of their respective claims via diplomatic channels. Despite diplomats’ awareness of the liberated Africans’ plight in Brazil, their treatment did not feature in these negotiations because it was not intelligible under the logic of compensation. Instead, the Brazilian government insisted that it had authority over the liberated Africans, and in 1864 it ended their apprenticeships.

In 1866, the British minister at Rio forwarded the Brazilian compensation cases to Whitehall, arguing that only twenty-eight of the ninety-eight original claims were worthy of consideration. In 1871, Henry Rothery, the Treasury's advisor in Doctors’ Commons (for admiralty matters), reassessed these remaining Brazilian claims. He explicitly disqualified from consideration the cases of Activo and Perpetuo Defensor from which the recaptives had escaped in 1826. Rothery declared that the commissary judges and Law Officers were wrong to award conditional compensation.Footnote 97 Extraordinarily, he argued that the vessels “ought properly to have been condemned” in accordance with the contemporaneous treaties. And yet treaty law at the time clearly exempted slave ships that were on routes south of the equator, as the two ships had been.

Rothery was not so much a final arbiter of anti-slave-trade law as he was engaged in an elaborate act of determining value. His performative claim was a kind of ex post facto financial free soil.Footnote 98 Perhaps Rothery was deliberately obstructing any attempt to commensurate the rival British and Brazilian claims. Following his advice that only five Brazilian claims were valid, the Foreign Office drily observed that the discrepancy between the claims now amounted to £122,568. 15s. “in favour of this country, instead of a balance, as has always been supposed, in favour of Brazil.”Footnote 99

When the Foreign Office communicated its new position, the Brazilian government was unimpressed. A report criticized Britain's lack of “moderation” and defended the validity of Brazil's twenty-eight claims.Footnote 100 The Brazilian government did not try to come to an agreement. Instead, the Conselho do Estado, the highest political authority in Brazil, focused its energies on criticizing Britain's anti-slave-trade policies. It claimed that their policies violated the “Direito dos Gentes” (law of nations), which commanded sovereigns to respect each other's territories and territorial waters in peacetime.Footnote 101 This criticism had little effect—the Conselho had no means to compel Britain to acknowledge its supposed rights—but it tellingly shifted Brazil's stance away from attempted value exchange and toward a defense of state sovereignty. Unsurprisingly, the Anglo-Brazilian Claims Commission fizzled out in 1875.

On the Upper Guinea Coast, British agents based at Sierra Leone and African chiefs engaged in overlapping strategies of value exchange and violence, even as British protectorate jurisdiction expanded over certain chiefs. By contrast, on the Brazilian coast the prevailing norm was that sovereigns should resolve claims through commissions. That norm limited the efficacy of the mixed-commission court and led to the shock of naval aggression. To resolve that shock, the sovereigns turned to the only form they knew, another commission, which failed to determine the value of maritime commercial losses.

CONCLUSION

Regulating anti-slave-trade jurisdiction led to a pattern in which coercion and value exchange alternated, overlapped, and were mutually sustaining. Enforcement and regulatory patterns changed when specific local factors came together, such as liberated Africans’ initiative in making their cases visible to British agents, diplomatic priorities, metropolitan pressures, and local political authorities’ willingness to discuss abolition. All parties had interests in distinguishing between enslavement, captivity, and apprenticeship conditions. An expansive comparative Atlantic framework reveals the connections and mutual influences between the Upper Guinea Coast and Brazil, such as the courts of mixed commission and naval strategies. But more than that, this comparative framework reveals convergences. These included Siaka and the Brazilian government's “law of nations” defense of sovereign jurisdiction, the importance of diplomatic access for recording and protecting liberated Africans’ status, and elites’ imposition of commodified “value” on Africans’ lives, even during rescues from re-enslavement.

It is perhaps easier to explain how the pattern of regulation switched between coercion and value exchange than to explain why it did so. Part of the answer lies in the intrinsically double nature of “liberated Africans” as a category. The Africans had the opportunity to frame their situation under anti-slave-trade law, with treaty parties responsible for their treatment, or under a polity's municipal law. This doubling meant that anti-slave-trade legal regulation produced tension between prioritizing either the personal status of liberated Africans or the territorial authority of local sovereigns.

Within this structural tension, regulation switched between coercion and value exchange because of local agents’ discretionary power. These agents were often brokers and they could choose to be aggressive or concessive, to engage with or disengage from diplomacy. For example, Kellet, Denman, and Jones raided barracoons in similar ways, yet Kellet's actions have been largely forgotten. The main difference was that he left Bolama without engaging with Governor Nozolini or African chiefs there, whereas Denman and Jones entered long discussions with African political authorities regarding jurisdiction, treaties, and compensation.

Discretionary power did not operate in a vacuum. Local elites contributed to determining how law should be regulated, sometimes as peers to British agents, and always as their engaged critics. The Brazilian government chose to ignore British requests for information about liberated Africans at the Casa de Correção, and yet protested vigorously when the Cormorant attacked the fort at Paranaguá. Both events involved British agents intervening in Brazilian institutions such as prisons and forts. Yet Brazil's government was more willing to pass new abolition legislation in response to the latter case because it had more sovereignty over ships and forts, and valued them more highly, than it did liberated Africans. Coercion and value exchange resulted from discretionary action that had different effects depending on how far local political authority controlled territory and how much value local elites placed on what (and who) was affected by the action.

The interactions between Africans’ demands, discretionary power, and local elites point to a final paradox regarding sovereignty and the discourse of “civilization.” British agents may have regarded Brazil as a civilized (albeit weak) polity worthy of treatment according to the law of nations, unlike “uncivilized” African chieftaincies. Yet one result was a British assumption that Brazil's governing elites had little personal authority to stop slave-trading to and from Brazil: in a civilized polity, political authority and commercial activity were theoretically separate realms. By the same logic, African chiefs were “barbaric” partly because they did not separate political representation from personal commercial interest.Footnote 102 Yet such concentrated personal authority meant that British agents were willing to believe that African elites had greater discretion in conducting their maneuvers than did Brazilian elites. For if elite political responsibility resided at a personal level, then nuanced, interpersonal, responsive regulation was possible, leading to more flexibility between coercion and value exchange.

This difference in the perceived discretionary powers of local elites also explains why, on the Upper Guinea Coast in the period ca. 1850–1870, value exchange was still possible for both sides as a means of honoring treaties, agreements, and seasonal trading patterns. These negotiations depended on British recognition of African political authority. In Brazil, by contrast, British violence was a stimulus for Brazil taking sovereign control of abolition through a new law, which gave jurisdiction to its own court, the Auditoria Geral da Marinha in Rio. The Brazilian claims commission of 1858 sat after Brazil's successful enforcement of its own belated abolition law. The failed 1826 treaty between sovereigns haunted, rather than honored, the new commission's doomed negotiations over value. As tempting as it is to eulogize abolition as a story of progress toward human rights and rules-based international order, in reality abolition practices were most effective when they were most arbitrary. Abolition law and inter-polity order resided principally in assembled actors from Britain, Africa, Brazil, and the liberated African diaspora, and the processes they developed. Sometimes those processes worked most flexibly where discretion rather than sovereignty drove the legal field.