Introduction

Long-term maintenance treatment with antipsychotic medication is critical for the prevention of relapse and the mitigation of functional deterioration.Reference Hasan, Falkai and Wobrock1–Reference Caseiro, Pérez-Iglesias and Mata3 Antipsychotic medications are associated with a range of adverse events (AEs), with specific risks determined by a range of factors, including duration of exposure, dose, and class of medication prescribed. In general, high-potency conventional antipsychotics have higher rates of neurologic AEs, such as antipsychotic-induced parkinsonism or tardive dyskinesia, whereas some of the atypical antipsychotics are more often associated with weight gain and metabolic problems.Reference Correll, Manu, Olshanskiy, Napolitano, Kane and Malhotra4–Reference Hasan, Falkai and Wobrock8 These neurologic and metabolic AEs are associated with increased burden and impact on medication adherence, with the latter AEs potentially contributing to increased cardiovascular risk, morbidity, and mortality.Reference Al-Zoairy, Ress, Tschoner, Kaser and Ebenbichler9–Reference Daumit, Goff and Meyer11

The risks associated with antipsychotics have been extensively studied, including the relative risks for most of the available oral antipsychotics.Reference Leucht, Cipriani and Spineli12 Additional questions regarding the long-term safety of long-acting antipsychotics compared with their oral counterparts arise because of the relatively longer persistence of medication in the plasma, which represents the basis of this therapeutic modality. This is a potential source of concern if the medication has to be discontinued because of treatment-emergent AEs. Thus, it is important to have a comprehensive source of information pertaining to long-term safety (in terms of onset, duration, and extent of AEs) when evaluating the risk–benefit profile for any long-acting antipsychotics.

Aripiprazole lauroxil (AL) is a novel, long-acting injectable atypical antipsychotic indicated for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia.13 The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of AL for the treatment of acute exacerbation of symptoms in patients with schizophrenia were previously demonstrated in a pivotal 12-week phase 3 study comparing 2 dose regimens of AL (441 mg and 882 mg every 4 weeks [q4wk]) with placebo (hereafter known as the 12-week efficacy study).Reference Meltzer, Risinger and Nasrallah14, Reference Nasrallah, Newcomer and Risinger15 A 52-week, open-label extension study was subsequently carried out to evaluate the long-term safety and therapeutic effect of AL in patients with schizophrenia. A post hoc analysis of this study demonstrated the durability of therapeutic effect with AL in a subgroup of patients who entered the 52-week study after successful treatment with 1 of the 2 active AL doses in the 12-week efficacy study.Reference McEvoy, Risinger and Mykhnyak16 However, a detailed report of full safety results of the entire safety population has not been published. In this article, we present a comprehensive summary of the safety results of the 52-week, open-label study of AL in patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

This was an international, multicenter, 52-week, phase 3 safety study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01626456; EudraCT Number, 2012-003996-20) conducted during the period June 2012–April 2015. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with Good Clinical Practice Guidelines agreed by the International Conference on Harmonisation, 1997. The study protocol, amendments, and informed consent forms were approved by an independent ethics committee/institutional review board for each site. All patients provided written informed consent before entering the study.

Patients

Eligible patients were adults between 18 and 70 years with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition, Text Revision) and who previously had a clinically significant beneficial response to treatment with an antipsychotic medication other than clozapine.

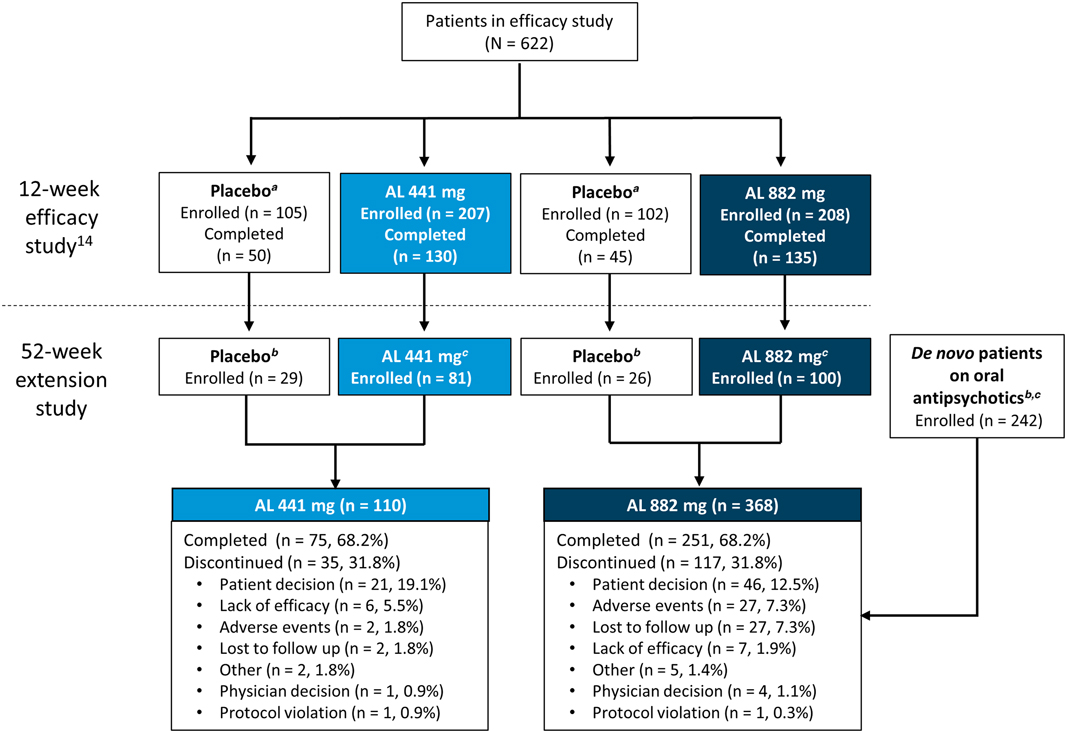

Study participants constituted 2 groups of patients: (1) those who had completed the 12-week efficacy study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01469039; EudraCT Number: 2012-003445-15)Reference Meltzer, Risinger and Nasrallah14 and had agreed to continue into the 52-week safety study and (2) newly recruited de novo outpatients who were prescribed a first-line oral antipsychotic before they entered the 52-week safety study (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Patient disposition. AL, aripiprazole lauroxil. a Matched low-volume/high-volume placebo. b Patients received active AL for the first time (with concomitant daily oral aripiprazole in the first 3 weeks) in the current 52-week study. Baseline assessments for weight and laboratory metabolic and endocrine parameters were defined as the last nonmissing value on or before the date of each patient’s first active AL administration in the current study. c Patients continued to receive active AL (with concomitant daily oral placebo in the first 3 weeks) in the current 52-week study. Baseline assessments for weight and laboratory metabolic and endocrine parameters were defined as the last nonmissing value on or before the date of each patient’s first active AL administration in the 12-week efficacy study. d Patients with schizophrenia stabilized on oral antipsychotics with no previous exposure to AL.

Patients who continued from the 12-week efficacy study had previously received 3 injections of either placebo or active AL (441 mg or 882 mg) q4wk, depending on randomization.

De novo patients were clinically stable (defined as no hospital admission for at least 3 months and Clinical Global Impression–Severity scale score ≤3 [mild] at screening), were receiving a stable dose of oral antipsychotic medication, and would potentially benefit from conversion to an extended-release injectable medication. Medical and psychiatric comorbidity exclusion criteria for de novo patients were similar to those previously described for patients from the 12-week efficacy study.Reference Meltzer, Risinger and Nasrallah14

52-week safety study design

The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety and tolerability of long-term treatment with AL in patients with stable schizophrenia. Patients in this study received up to 13 doses of AL administered by gluteal injection every 4 weeks over a 52-week treatment period.

Initial treatment steps depended on how patients entered the study. Patients entering this study from the 12-week efficacy study had already received 3 injections of randomized study medication (1 of 2 fixed doses of AL [441 mg or 882 mg] or volume-matched placebo injection). Patients previously assigned to the active (blinded) 441 mg or 882 mg AL treatment arm continued on their assigned AL dose. Patients previously assigned to the placebo arm started active AL at a fixed dose of either 441 mg or 882 mg q4wk based on the volume of their previous placebo injection (which had been volume-matched to either 441 mg or 882 mg AL injection). Patients in this group therefore received their first dose of active AL on entry into the current study. All patients also received a blinded oral study drug (either 15 mg aripiprazole or placebo) daily for the first 3 weeks (ie, 21 days) upon entry into the study. Patients who previously received placebo now received active oral aripiprazole, whereas patients who previously received AL (and concomitant oral aripiprazole for 21 days accordingly in the 12-week efficacy study) received placebo capsules. This method was necessary to maintain blinding of treatment assignment in the 12-week efficacy study, which was still ongoing at the time the patients entered the 52-week study.

Following screening and enrollment, de novo patients received their first dose of AL (882 mg). They also received daily oral aripiprazole supplementation for the first 21 days while being tapered off their current oral antipsychotic (which had to be fully discontinued by the time of their second AL injection visit 4 weeks later). These patients continued to receive AL 882 mg every 4 weeks thereafter. Further details of this patient population and a post hoc analysis of the clinical outcomes of the initial 12-week crossover period have been reported in a separate publication.Reference Weiden, Du and Liu17

Study assessments

Safety assessments included the following: AE assessment, injection-site examination, vital signs and weight measurement, completion of abnormal movement scales, laboratory tests, and 12-lead electrocardiogram. Selected AEs of special interest, including weight gain, metabolic parameters, and extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS; here defined broadly to cover akathisia, dyskinesia, dystonia, and Parkinson-like events), were monitored based on class effects observed with oral aripiprazole and other atypical antipsychotics. Parkinson-like events included tremors, extrapyramidal disorders, parkinsonism, drooling, and dysphonia. EPS were also assessed using the Simpson–Angus Scale (SAS), Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), and Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS). Safety assessments were carried out at every visit during the treatment period. Injection-site reactions (ISRs) were assessed at each visit and were reported as AEs by type (pain or other) and severity (mild, moderate, or severe).

A secondary outcome of interest was psychiatric hospitalizations (which were not automatically listed as a serious AE). Hospitalization rates were summarized and compared during the 12-, 9-, 6-, and 3-month periods before and after treatment. For patients who previously received AL, the full pretreatment period was the 12-month period before the first dose of AL in the 12-week efficacy study, and the full posttreatment period was the 12-month period starting after the first dose of AL in the current study (the 3-month AL treatment period in the 12-week efficacy study was excluded). For de novo patients and patients who previously received placebo, the full pretreatment and posttreatment periods were the 12-month periods before and after the first dose of AL in the current study, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Safety analyses were assessed in all patients who received at least 1 dose of AL. Analyses were descriptive, including mean, standard deviation (SD), and mean change from baseline to the last recorded value obtained during the treatment period.

AEs were reported for the duration of the 52-week treatment period for all patients. Certain AEs—notably akathisia and ISRs—have been associated with the first few weeks of AL initiation.Reference Meltzer, Risinger and Nasrallah14 As such, additional post hoc subgroup analyses (by previous treatment) were carried out in certain instances to examine the association between AEs and initiation of drug or injections. All data were presented without additional formal statistical comparisons.

For all patients, baseline assessments for weight and laboratory metabolic and endocrine parameters were defined as the last nonmissing value on or before the date of the first active AL administration. Hence, for patients who previously received AL, these would be values at the start of the 12-week efficacy study. In contrast, baseline values for patients who previously received placebo in the 12-week efficacy study would be values at the start of the current 52-week study; this also applied to the de novo patients.

Results

Patients

In total, 478 patients received at least 1 dose of active AL in this 52-week safety study, with 76.9% (n = 368) of patients receiving the 882 mg dose and 23.2% (n = 110) receiving the 441 mg dose. Figure 1 describes the lead-in status of the patients (either continuing from the 12-week efficacy study or de novo) before enrollment in the current study and the disposition of the patients according to the 2 AL dose groups. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were comparable across all groups (presented by lead-in treatment; Table 1). Most patients were male (57.5%; n = 275) and white (63.8%; n = 305); the median age of the patients was 39.4 years.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics

AL, aripiprazole lauroxil; BMI, body mass index; q4wk, every 4 weeks; SD, standard deviation.

All values are expressed as mean (SD), unless otherwise indicated.

a Patients receiving low-volume placebo and AL 441 mg in the 12-week efficacy study assigned to receive AL 441 mg in the long-term study.

b Patients receiving high-volume placebo and AL 882 mg in the 12-week efficacy study and de novo patients assigned to receive AL 882 mg in the long-term study.

In total, 68.2% (n = 362) of all patients completed the study (Figure 1). Overall, 75.5% of patients received ≥9 injections, and 68.8% of patients received 13 injections of AL over 52 weeks. The most common reason for early termination was withdrawal of consent by the patient (14.0%; n = 67). In total, 15 patients received open-label oral antipsychotic medication for a psychotic flare-up during the course of the study; 10 patients continued in the study following resolution of symptoms, while 5 patients were discontinued from the study.

Safety

Adverse events

Overall, AEs during the treatment period were reported in 50.4% (n = 241) of patients; most were mild or moderate in intensity (Table 2). Serious AEs (SAEs) were reported in 3.1% (n = 15) of patients, leading to study discontinuation in 10 of the 15 patients (2.1%). All SAEs occurred in the AL 882 mg group. Two SAEs resulted in death, the first due to cardiopulmonary arrest following an accidental gunshot wound (assessed by investigator as probably not related to the study drug) and the second due to a suicide associated with worsening of schizophrenia symptoms (assessed by investigator as possibly related to the study drug).

Table 2 Overview of AEs

AE, adverse event; AL, aripiprazole lauroxil; SAE, serious adverse event; q4wk, every 4 weeks.

a One patient who discontinued because of weight gain was not included because the AE occurred before the first injection in the long-term study.

b Patients who experienced more than one AE in any category were counted only once in that category.

c 16 of 17 (94%) events were reported in de novo patients who received their first injection in this study.

AEs leading to discontinuation were reported in 5.9% (n = 28) of the total population and occurred more frequently among patients in the AL 882 mg group than in the 441 mg group (7.3% vs 0.9%, respectively) (Table 2). The most common AEs leading to discontinuation were reported under the system organ class of “psychiatric disorders” (including schizophrenia as the most frequent; n = 11), which occurred in 3.6% (n = 17) of the total population, likely representing a worsening of the primary disease. Of these 17 patients, 16 were from the AL 882 mg group. These safety results were also analyzed by lead-in treatment on entry into the current study (Table S1, available online in the Supplementary Material). In total, 12 of the 15 patients in the AL 882 mg group who experienced a SAE were patients without previous exposure to AL who started active AL (along with 21 days of oral aripiprazole supplementation) upon study entry (ie, the prior-placebo and de novo groups). Similarly, the majority of patients on AL 882 mg who discontinued due to an AE (22 of 27 patients) were in this patient group.

The most frequently reported AEs overall were insomnia (8.4%), weight increased (5.0%), and anxiety (4.4%). Similar incidences of AEs were reported in the individual doses (46.4% and 51.6% in the 441 mg and 882 mg AL groups, respectively). Patients receiving 882 mg had a higher incidence of insomnia, injection-site pain, akathisia, and tremor than patients receiving 441 mg (Table 2), possibly because a higher proportion of patients in the 882 mg group than the 441 mg group started AL on study entry. Results of post hoc analysis examining the association between akathisia and ISRs with the initiation of AL are presented in the following sections.

Adverse events of interest

Injection-site reactions

The overall incidence of ISRs for the entire safety population was 4.8% (n = 23/491); most of the ISRs were reported as injection-site pain events (n = 18/23; 78%), and of these, 14 events were considered mild. A higher frequency of injection-site pain was observed in the AL 882 mg group (4.6%; n = 17) than in the AL 441 mg group (0.9%; n = 1) (Table 2). The mean duration of injection-site pain was 6.3 days, and the median was 3.0 days (n = 18).

Examination of the pattern of ISR occurrence by lead-in treatment (Table 3) showed that most ISRs were reported in the de novo patients who received their first injection in this study (N = 242), with 8.3% (n = 20) reporting ≥1 event; injection-site pain was the most common ISR. Patients entering the current study after previously receiving 3 injections in the 12-week efficacy study (AL [N = 181] and placebo [N = 55]) had a lower incidence of ISRs (1.7% [n = 3] and 0% of patients, respectively) than de novo patients (Table 3). Most ISRs were associated with the initial injections and decreased in frequency at subsequent injection visits (Table 3).

Table 3 Summary of ISRs by the associated injection and lead-in treatment group

AL, aripiprazole lauroxil; ISR, injection-site reaction.

The number of patients experiencing any ISRs from the fourth injection onward ranged from 0 to 5 per injection. All values are expressed as n/m (%), where m represents the number of evaluable patients, unless otherwise indicated.

a The first injection in the long-term study was the first exposure to AL (882 mg).

b Previously received 3 injections of AL in the acute-phase study; the first injection in the long-term study was the fourth exposure to AL (441 or 882 mg).

c Previously received 3 injections of placebo in the acute-phase study; the first injection in the long-term study was the first exposure to AL (441 or 882 mg).

d Calculated as percentage of any ISRs.

e Some patients reported multiple ISRs over the course of the study.

f Some patients reported multiple injection-site pain events over the course of the study; of 18 patients who reported injection-site pain, 14, 3, and 1 patients experienced a maximum severity of mild, moderate, and severe, respectively.

Extrapyramidal symptoms

Overall, 9.4% (n = 45) of patients reported AEs associated with EPS (here broadly defined to encompass akathisia, dyskinesia, dystonia, Parkinson-like events, and restlessness), at an incidence of 4.5% (n = 5) for the 441 mg group and 10.9% (n = 40) for the 882 mg group (Table 2). None of the events were severe or serious. Three patients in the 882 mg group discontinued the study because of EPS-associated AEs (2 akathisia, 1 Parkinson-like event).

With regard to individual EPS symptoms, the frequencies of dyskinesia and dystonia were low and similar for both dose groups (Table 2). Higher incidences of akathisia (4.6% vs 0.9%) and Parkinson-like events (5.4% vs 1.8%) were reported in the AL 882 mg group than in the AL 441 mg group (Table 2). To explore possible reasons for the apparent differences, the incidences of akathisia and other EPS were investigated in patients subgrouped by previous AL exposure (Table S2). This analysis showed that most of the akathisia AEs (83%; 15 of 18 events) occurred in the subgroup of patients who initiated AL and aripiprazole supplementation when they entered this safety study. Most of the akathisia events in this study occurred early during treatment: 3.1% (n = 15) of patients in the first 3 months of the study, 0.2% (n = 1) in the following 3 months, and 0.8% (n = 3) of patients in the subsequent 3 months. No akathisia events were reported after the ninth month.

The incidence of Parkinson-like events did not seem to be related to whether a patient started AL at the time of study entry because the incidence was comparable in all 3 subgroups: 5.0%, 3.9%, and 5.5% in the de novo, prior AL, and prior-placebo subgroups, respectively (Table S2).

Overall, the changes in the structured abnormal movement scales (SAS for antipsychotic-induced Parkinsonism, BARS for akathisia, and AIMS for dyskinesia) were minimal, and the mean total score remained relatively constant over time in all treatment groups for all 3 scales.

Body weight and body mass index

Long-term exposure to AL resulted in a small mean increase in body weight (0.8 kg) and body mass index (BMI) score (0.3) from baseline to the last recorded assessment overall (Table 4). Of the 351 patients who received treatment throughout the 52 weeks, 25 (7.1%) and 12 (3.4%) had weight gains of >10 kg and >15 kg, respectively. Potentially clinically significant increases in body weight of ≥7% occurred in 18.4% (n = 88) of patients, whereas ≥7% decreases in body weight occurred in 12.3% (n = 59) of patients (Table 4). AEs of increased weight were reported in 6.4% (n = 7) and 4.6% (n = 17) of patients in the 441 mg and 882 mg groups, respectively (Table 2).

Table 4 Baseline values and changes in body weight, BMI, metabolic and lipid parameters, and prolactin

AL, aripiprazole lauroxil; BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; q4wk, every 4 weeks; SD, standard deviation.

a Values are expressed as mean (SD) unless otherwise noted.

b Change to last postbaseline value during the treatment period.

Glycemic control and lipid parameters

Long-term treatment with AL was associated with relatively modest increases in fasting glucose and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels (Table 4). No clinically meaningful changes were observed for any glycemic-control or lipid parameters (Table 4). AEs related to metabolic parameters were reported in 3.6% (n = 4) and 4.9% (n = 18) of patients in the AL 441 mg and 882 mg groups, respectively. The most frequently reported AE related to metabolic parameters in the 441 mg group was increased HbA1c (n = 3); the most frequently reported AEs in the 882 mg group were hyperglycemia (n = 4), increased HbA1c (n = 3), and diabetes mellitus (n = 3). Type 2 diabetes mellitus was reported in 1 and 2 patients in the 441 mg and 882 mg groups, respectively. An AE of glucosuria was also reported in 1 patient in the 882 mg group. A SAE of hyperglycemia was reported in 1 patient in the 882 mg group, resulting in study discontinuation.

Prolactin

Overall baseline prolactin levels were 13.3 and 30.4 ng/mL for male and female patients, respectively, with normal levels defined as 4.0 to 15.2 ng/mL for males and 4.8 to 23.3 ng/mL for females. Mean serum prolactin levels decreased from baseline to the last postbaseline assessment in both sexes, with a decrease in mean serum prolactin of 8.7 ng/mL for males and 14.9 ng/mL for females overall (Table 4).

The trajectory of prolactin level change is better understood in the context of the patients entering the safety study with prolactin elevations (with potentially clinically significant values defined as ≥1 to ≥3 times the upper limit of normal [ULN]). Overall, 22.5% (n = 59) of males and 34.7% (n = 68) of females had prolactin elevations ≥3 × ULN at baseline. Among this subgroup with elevated baseline levels, 72.9% of males (n = 43) and 61.8% (n = 42) of females had at least 1 follow-up prolactin level within the normal range.

In total, 151 male and 110 female patients had nonpotentially clinically significant prolactin values at baseline. Among these patients, 10 (6.6%) male and 21 (19.1%) female patients had potentially clinically significant values at any postbaseline visit that were ≥1× to ≥3 × ULN (Table S3). Two female patients had potentially clinically significant values ≥3 × ULN, but both completed the study and neither had any AEs associated with prolactin. The proportions of males and females who experienced shifts from normal or low prolactin at baseline to ≥3 × ULN at any postbaseline visit were 5.4% and 15.6%, respectively. Five (1.4%) patients in the 882 mg group (but none in the 441 mg group) reported AEs associated with prolactin; none were considered severe.

Other laboratory or safety measures

No clinically relevant changes in clinical safety laboratory tests, vital signs, or electrocardiography values were observed.

Hospital admission outcomes

Fewer patients were admitted to the hospital for psychiatric events in their posttreatment period compared with their corresponding pretreatment period. The crude rates of psychiatric hospital admissions during the 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month pretreatment periods were 15.0%, 19.7%, 27.2%, and 30.7%, respectively, whereas rates during the 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month posttreatment periods were 2.0%, 3.0%, 3.5%, and 3.5%, respectively.

Discussion

Patients with schizophrenia require ongoing treatment with antipsychotic medication. Thus, evaluating the long-term tolerability and safety of an antipsychotic agent is clearly important when selecting one for maintenance treatment. Results of the current study showed that treatment with 441 mg or 882 mg AL for up to 52 weeks in patients with schizophrenia was well tolerated and had a high completion rate (68.2%). In general, the safety and tolerability profile of AL in the current 52-week study was consistent with that reported in the 12-week efficacy study, demonstrating a low risk for metabolic abnormalities and modest weight gain.Reference Meltzer, Risinger and Nasrallah 14 , Reference Nasrallah, Newcomer and Risinger 15 No new safety events were observed during the 52-week treatment period.

In this study, treatment with AL 882 mg was associated with a higher incidence of SAEs, discontinuations due to AEs, insomnia, akathisia, tremor, and injection site pain than treatment with AL 441 mg. However, interpretation of any apparent dose-related findings should take into account the fact that most (66%) patients in the 882 mg group were de novo patients who were not previously exposed to AL and that a greater proportion of patients in the 882 mg group (72.8%) compared with patients in the 441 mg group (26.4%) had their first exposure to AL in the current study. Hence, AEs that are generally associated with initiation of AL were captured in disproportionately greater numbers in the 882 mg group compared with the 441 mg group. Indeed, most of the SAEs and discontinuations occurred in this patient population. Overall, the safety profile of AL was generally consistent with previously reported long-term safety profiles of oral aripiprazole and aripiprazole once-monthly (400 mg) long-acting injectable.Reference Croxtall 18 – Reference Peters-Strickland, Baker and McQuade 20

The overall incidence of ISRs in this study was low. As anticipated, ISRs occurred more frequently in the de novo patients receiving their first AL injection than in patients from the earlier 12-week efficacy study who were receiving their fourth intramuscular (IM) injection. We were particularly interested in the patients who had previous exposure only to placebo injections and were receiving active AL for the first time, because this provided an opportunity to investigate the extent to which ISRs are due to injection procedures rather than to the active AL suspension. The observation that no new ISRs were reported in the 55 patients who entered the safety study from the placebo arm of the earlier 12-week efficacy study (and had presumably become accommodated to IM injections) supports the idea that ISRs were associated with the novelty of the initial injections rather than the study drug per se. The incidence of ISRs in the de novo patients (8.3%) was higher than that reported for the 12-week efficacy study (3.9% [AL 441 mg] and 5.8% [AL 882 mg]).Reference Meltzer, Risinger and Nasrallah 14 As in that study, the rate of ISRs decreased as a function of injection number over time.Reference Meltzer, Risinger and Nasrallah 14

Overall, the incidence of broadly defined EPS-related AEs with AL was low, and none were considered severe or serious, which is consistent with the known safety profile of aripiprazole. The higher akathisia rates in the 882 mg group compared with the 441 mg group (4.6% vs 0.9%) were driven primarily by patients who were receiving AL for the first time in the study, confirming the association between akathisia and AL initiation (and concomitant oral aripiprazole). As in the 12-week efficacy study, most of the akathisia episodes occurred during the initial phases of the study when concomitant oral aripiprazole was being administered, supporting the idea that the combined exposure of oral aripiprazole and injected AL might have contributed to the incidence of akathisia. The overall frequency of Parkinson-like events (including tremor) was low (4.6%), and was also reported at a higher frequency in the 882 mg group (5.4%) than in the 441 mg group (1.8%). Unlike the akathisia events, these events did not appear to correlate with any particular lead-in treatment in the 882 mg group (Table S1), raising the possibility that the incidence of Parkinson-like events might be dose related.

Consistent with results of the 12-week efficacy study, results of the current study demonstrate that AL caused few clinically relevant metabolic parameter AEs in patients with schizophrenia and that AL is effective at limiting the pronounced weight gain and other metabolic risks commonly encountered with other antipsychotics.Reference Nasrallah, Newcomer and Risinger 15 Increases in mean body weight and BMI index were minimal over the course of the study; in this study, an increase of ≥7% in body weight was observed in 18.4% of patients over 52 weeks, which compared favorably with results from a 52-week, randomized, double-blind trial evaluating olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone (range, 50%–80%).Reference McEvoy, Lieberman and Perkins 21 Minimal changes from baseline to last postbaseline assessment were observed for lipid and glycemic parameters and for plasma glucose and HbA1c levels, consistent with observations in other studies of oral aripiprazole.Reference Nasrallah, Newcomer and Risinger 15 , Reference Kane, Sanchez and Perry 19 , Reference Guo, L'Italien and Jing 22 , Reference Potkin, Raoufinia and Mallikaarjun 23 Treatment with AL was associated with decreased mean prolactin levels below baseline toward the normal range, which is consistent with previous studies of aripiprazole in patients with schizophrenia.Reference Nasrallah, Newcomer and Risinger 15 , Reference Kane, Sanchez and Perry 19 , Reference Kane, Peters-Strickland and Baker 24

A limitation of this study was the lack of a placebo group, which limited the ability to attribute any specific outcomes to treatment with AL. In addition, the selective inclusion of patients who successfully completed the 12-week efficacy study may limit the generalizability of the study results because this might have resulted in the preferential selection of a study population who derived benefit from AL treatment while excluding patients who did not respond or who had adverse reactions to AL treatment. However, inclusion of newly enrolled (de novo) patients allowed for the evaluation of AL in a nonselected cohort of patients. Evaluation of any apparent dose-related effects in this study should take into account the fact that these patients received their first injection and their first exposure to AL in this study. Finally, the inclusion criteria precluded the possibility of drawing conclusions regarding the tolerability of AL in “first episode” or antipsychotic-naïve patients. As these patients have been shown to display high rates of AEs with antipsychotics,Reference Robinson, Gallego and John 25 clinicians might need to bear this in mind when considering AL treatment for these patients.

The results of this study demonstrate the safety and tolerability of long-term treatment with AL in patients with schizophrenia, with a safety profile consistent with that of oral aripiprazole and with no unexpected safety concerns during the 1-year, long-term study, thus addressing clinical concerns regarding long-term safety with continued AL therapy.

Disclosure

Henry Nasrallah has the following disclosures: Alkermes, personal fees; Acadia, personal fees; Allergan, personal fees; Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees; Janssen, personal fees, Lundbeck, personal fees; Neurocrine, personal fees; Otsuka, personal fees; Sunovion, personal fees; Teva, personal fees; Vanda, personal fees; and Forum, personal fees. Ralph Aquila reports personal fees from Alkermes during the conduct of the study, personal fees from Otsuka, personal fees from Sunovion, and personal fees from Janssen, outside the submitted work. Yangchun Du, Arielle Stanford, Amy Claxton, and Peter J. Weiden, are employees of and hold stock in Alkermes.

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852918001104