Patients with psychiatric disorders receive various treatment modalities for their illness. Conventionally, clinicians increase medication dose (dose optimization) when the patient does not show response in a relatively lower dose. The persistence of nonresponse compels the clinician to augment the therapy with other pharmacological agents, psychotherapy, or somatic treatments. Alternatively, the clinical practice guidelines recommend switching to another psychotropic medication of a different category or combining more than one psychotropic drug if the psychiatric illness persists without substantial improvement.Reference Taylor, Barnes and Young 1 Conventionally, augmentation strategies are introduced to the treatment plan late in the course of therapy, after failed trials of monotherapy (dose optimization and switching of medication).Reference Arumugham and Reddy 2 , Reference Taylor, Marwood and Oprea 3 By that time, patients’ sufferings, disabilities, functioning, productivity, and attitude toward therapy are adversely affected. Early augmentation in the management of psychiatric disorders is a new concept. It may help in the early reduction of the symptoms, early remission, and early gaining of functionality, resulting in early return to work (reduced absenteeism). Evidence supports that early achievement of remission is key to treatment success.Reference Kupfer 4 , Reference Nelson, Pikalov and Berman 5

In a study, patients with major depressive disorder with inadequate response to antidepressants received early augmentation with antipsychotic medications. It was found that the patients receiving early augmentation had reduced healthcare expenditure.Reference Yermilov, Greene and Chang 6 Augmenting pharmacotherapy with cognitive behavior therapy in obsessive–compulsive disorder is found to be more effective in reducing the symptoms severe cases of obsessive–compulsive disorder.Reference Guzick, Cooke and Gage 7 , Reference Skapinakis, Caldwell and Hollingworth 8 In most conditions, psychotherapy (eg, cognitive behavior therapy) is introduced early in the course of treatment as an addition to the pharmacotherapy. Here, the argument is: If early augmentation of pharmacotherapy with psychotherapy gives better outcomes in various psychiatric disorders, then why not the novel neuromodulation techniques should be used as an early augmentation to treat psychiatric disorders. Early augmentation with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) has been tried in a patient after 4 weeks of initiation of antidepressant treatment, and there was a substantial reduction of depressive symptoms with this strategy.Reference Singh, Singh and Kar 9

Electroconvulsive therapy is one of the favored options for augmenting pharmacotherapy in schizophrenia.Reference Phutane, Thirthalli and Kesavan 10 Notwithstanding the evidence base favoring Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), questions surrounding its efficacy and cognitive side effects have impeded use of ECT, and it is often relegated to a last resort measure barring patient deemed to be at high risk for suicide. In this regard, a recent systematic review found that such concerns were not supported by evidence; ECT augmentation resulted in minimal cognitive side effects and, on the contrary, improved cognition in some cases.Reference Ali, Mathur and Malhotra 11

Treatment resistance is an issue in chronic schizophrenia and about a quarter of cases with first-episode psychosis.Reference Bozzatello, Bellino and Rocca 12 One study has demonstrated short-term clinical effectiveness of ECT in first-episode schizophrenia.Reference Uçok and Cakir 13 Given the benefits of early intervention on clinical, social, and vocational outcomes in first-episode psychosis, rapid access to a range of comprehensive interventions is important in the first few weeks following the onset of psychosis.Reference Drake, Husain and Marshall 14

A consistent body of evidence points to the neurotoxic effects of depression,Reference Sapolsky 15 including the length of depressive episodes.Reference Gorwood, Corruble and Falissard 16 Thus, it is essential to treat depression faster to reduce untreated illness duration and aim for complete remission.Reference de Diego-Adeliño J, Portella and Puigdemont 17 Supporting this assertion, a study using a decision-analytic model found that earlier introduction of ECT, following the failure of two lines of pharmacotherapy/psychotherapy was associated with lesser time spent in uncontrolled depression and greater cost-effectivenessReference Ross, Zivin and Maixner 18 ; this implies that ECT can be an optimal third line strategy for major depression as opposed to the prevailing view of ECT as a last-resort treatment option for depression.Reference Dauenhauer, Chauhan and Cohen 19

Cognitive deficits are a crucial feature of early-phase schizophrenia and are strongly linked to poor social and vocational outcomes.Reference Sponheim, Jung and Seidman 20 Hence, there is a need to develop and evaluate new treatments that may ameliorate cognitive deficits in schizophrenia and improve outcomes and functioning. In this connection, preliminary evidence of clinical efficacy was noted in a pilot randomized controlled trial of high-frequency rTMS for cognitive dysfunction in early phase psychosis.Reference Francis, Hummer and Vohs 21 Interestingly, benefits on cognition extended beyond the treatment endpoint and continued in follow-up; the authors ascribed this to mechanisms such as long-term potentiation or meta-plasticity, which may influence neuronal networks post-treatment.

Likewise, early rTMS application’s potential utility to accelerate and augment response to pharmacotherapy in significant depression was highlighted nearly two decades ago.Reference Padberg and Möller 22 Subsequently, a meta-analysis of six Randomized Control Trial (RCTs) found significantly higher treatment response rates for add-on high-frequency rTMS in subjects with major depressionReference Berlim, Van den Eynde and Daskalakis 23 while also being a safe and acceptable treatment; these findings have relevance to real-world practice because early response and remission in depression may be associated with better neurobiological and psychosocial outcomes.Reference Colla, Kronenberg and Deuschle 24 , Reference Machado-Vieira, Salvadore and Luckenbaugh 25 Early introduction of rTMS in depression after one failed pharmacologic treatment, in other words, nontreatment resistant cases, has proved clinically efficaciousReference Voigt, Carpenter and Leuchter 26 and cost-effective in the long run.Reference Voigt, Carpenter and Leuchter 27

There is growing evidence supporting the beneficial role of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in managing various psychiatric disorders ranging from schizophrenia, depression, substance use disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder to neurocognitive disorders.Reference Thair, Holloway and Newport 28 In most of the studies, tDCS is used as an augmentation strategy to the ongoing pharmacotherapy procedure. A study on patients with depression (who were inadequate responders to treatment) found that augmentation of the ongoing antidepressant treatment with tDCS produces an acute beneficial response.Reference Dell’Osso, Zanoni and Ferrucci 29 Researchers used tDCS as an augmentation strategy for the ongoing exposure therapy in patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder and phobic disorder. It was found that there is rapid improvement in the symptoms following tDCS intervention.Reference Cobb, O’Connor and Zaizar 30

A systematic review of neuropsychological and neuroimaging studies of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders, reported that the clinical effect of tDCS is closely linked with symptom severity.Reference Chan and Han 31 This finding suggests that when the symptoms are more severe (in the acute phase), choosing tDCS as early augmentation strategy may help reduce the symptoms.

There are certain challenges with early augmentation:

-

• Early augmentation may increase the cost of therapy at the initiation of care (additional cost for augmentation treatment).

-

• It will not be easy to anticipate whether the clinical improvement is due to the core treatment modality or add-on treatment modality, or combined effect.

-

• The risk of side effects may be high. Early augmentation enhances the action of the primary treatment modality. It may increase the risk of side effects too.

-

• Identifying the predictors of response is vital for opting for early augmentation. Researchers identified predictors of response to various treatment modalities for various psychiatric disorders.Reference Kar 32 , Reference Kar and Menon 33

-

• There is a lack of robust evidence regarding the role of early augmentation of neuromodulation techniques in managing psychiatric disorders due to the paucity of research.

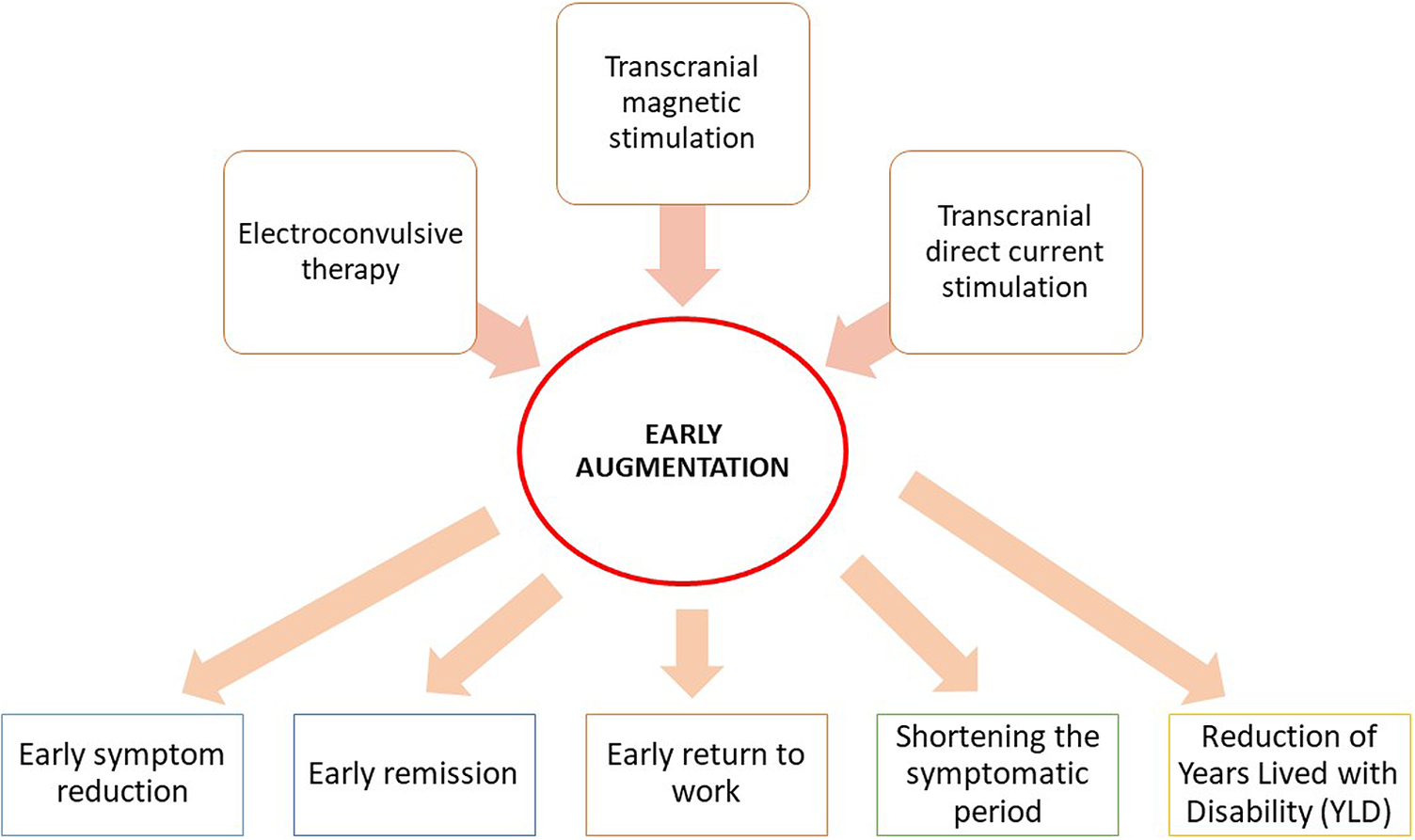

Figure 1 summarizes neuromodulation strategies that may be used in early augmentation and their expected benefits. The conventional treatment guidelines recommend neuromodulation techniques as augmenting strategies (mostly) in managing treatment-resistant/refractory cases of psychiatric disorders. Mostly, these strategies are introduced to the patient late in the course of treatment. However, early augmentation of the ongoing pharmacological or psychological treatment can be done using various neuromodulation strategies, which may produce early symptom reduction or remission and early return to work by resuming functionality. Early augmentation may curtail the duration of the symptomatic period. There is a need for extensive research to evaluate the need for early augmentation in current psychiatric practice.

Figure 1. Neuromodulation techniques as early augmentation treatment.

Disclosures

The authors do not have anything to disclose.