Since the introduction of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) in 2014 as a clinical entity, there have been many unanswered questions. There is an ongoing debate about its nosology, since the chronic persistent irritability in children and adolescents has contextual valence. In the last few years, different types of treatment studies have also yielded mixed results (Table 1). These findings further widen the debate given its clinical utility for patients, families, and practicing clinicians. The widespread criticism about the validity of DMDD predates 2014. There is no consensus on evidence-based treatment strategies for DMDD, and the aim is to examine the hypothesis if there is a high variance in treatment responses in the recent empirical research. We performed a literature search from Psych INFO, PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar until 2021. The search strategy included the following key terms: “adolescents,” “ADHD,” “aggression,” “bipolar disorder,” “children,” “disruptive behaviors,” “irritability,” “oppositional defiant disorder,” “ODD,” “rage,” “temper outbursts,” and “treatment” as main subject headings or text words in titles and abstracts. We identified n = 20 relevant articles among which 11 were specific about treatment, and others highlighted issues with the validity of the diagnosis.

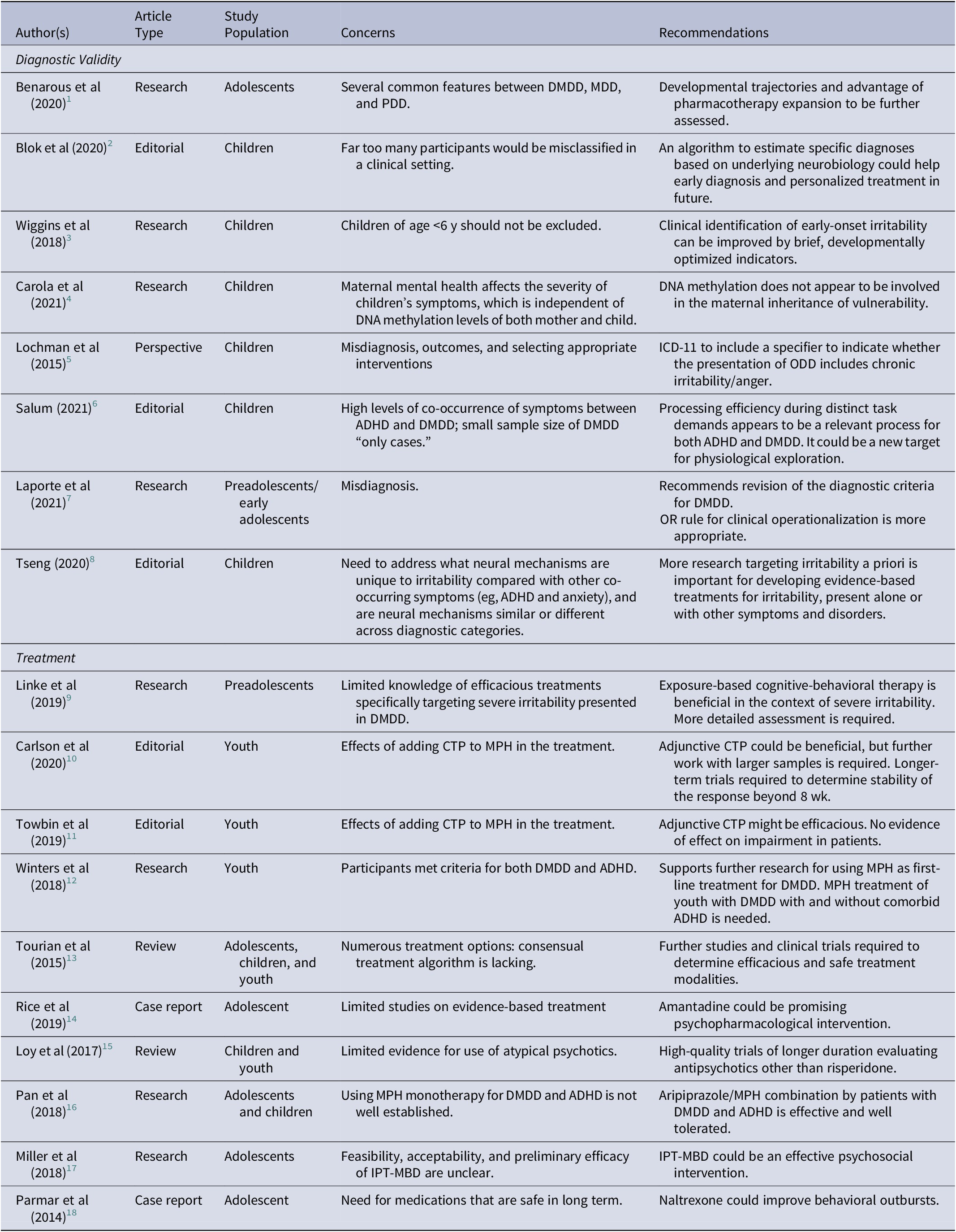

Table 1. Summary of Studies.

Abbreviations: CTP, citalopram; DMDD, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder; IPT, interpersonal therapy; IPT-MBD, interpersonal psychotherapy for mood and behavior dysregulation; MPH, methylphenidate.

The emerging evidence is weak. But it strengthens the chorus challenging the validity of DMDD due to its overlapping symptoms with oppositional defiant disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and major depressive disorder. A promising diffusion tensor imaging study reported discrete alternations in white matter microstructure in DMDD as compared to altered myelination in bipolar disorder. The epigenetic mechanisms of hypermethylated DNA were also studied to link it with its possible etiology without success. The psychopharmacological treatment studies used stimulant medication, antidepressants, antipsychotics, amantadine, and naltrexone with limited generalizability. Interpersonal therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and parent management training have some efficacy in symptom reduction. It is also suggested to revise the age of onset in the diagnostic criterion, because it excludes children of age <6 years, and the core symptoms are present in early childhood, and subsequently, its impairments when left untreated have poor overall outcomes.

The rationale for creating DMDD as a separate category has been counterintuitive and led to diagnostic uncertainly and hesitancy among clinicians. The limited evidence suggests a more heterogeneous condition with symptoms overlapping of other disorders and responds to diverse strategies. Although chronic persistent irritability is the area of focus for new research, more clarity is needed.

Acknowledgment

None.

Funding Statement

The work received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure

The authors do not have anything to disclose.