Introduction

Rationale

Akathisia can be provoked by a wide variety of agents, particularly antipsychoticsReference Salem, Nagpal and Pigott 1 and, to a lesser extent, antidepressantsReference Friedman 2. It represents a significant challenge in the field of neuropsychiatry and afflicts a substantial portion of patients, with prevalence rates estimated to be as high as 30% in patients treated with antipsychotics.Reference Berna, Misdrahi and Boyer 3 Despite its frequency, akathisia remains an enigmatic phenomenon, characterized by difficulties in patient self-reporting, diagnostic accuracy, and treatment efficacy, thereby posing a vexing problem for healthcare practitioners.Reference Sienaert, van Harten and Rhebergen 4

Derived from the Greek term meaning “inability to sit,” akathisia was initially described by Czech neuropsychiatrist Ladislav Haškovec in 1901Reference Mohr and Volavka 5. Although it is now recognized as predominantly drug-induced, it was not until the 1950s that akathisia became associated with the use of neuroleptic drugs.Reference Kern, Lang and Friedman 6

Akathisia is characterized by both subjective experiences and observable manifestations of restlessness and excessive movements. 7

Patients commonly report feelings of inner restlessness and discomfort, accompanied by physical symptoms such as leg fidgeting, rocking back and forth, pacing, and an inability to remain seated or stationary.

The pathophysiology of akathisia has been primarily attributed to an imbalance between dopaminergic and serotonergic/noradrenergic neurotransmitter systems.Reference Adler, Angrist and Reiter 8 , Reference Poyurovsky and Weizman 9 Alternative theories have been proposed to explain the underlying mechanisms of akathisia. One such theory involves overstimulation of the locus ceruleus that leads to a mismatch between the core and shell. Disruptions in this circuitry may contribute to the motor restlessness and agitation observed in akathisia.Reference Stahl and Lonnen 10 More recently, a model involving D2/D3 receptor occupancy in the ventral striatum and new pathophysiological mechanisms related to neuroinflammation, damage to the blood–brain barrier, and/or impaired neurogenesis have also been implicated in the onset of akathisia.Reference Salem, Nagpal and Pigott 1

Akathisia presents several challenges beyond being easily overlooked. One significant issue is its impact on medication adherence. The discomfort and distress caused by akathisia can lead patients to discontinue or reduce their medication, as they associate it with the exacerbation of their symptoms.Reference Sienaert, van Harten and Rhebergen 4 This nonadherence can further complicate the management of the underlying condition and potentially lead to treatment failure. Another problem arises from the potential misinterpretation of akathisia as a deterioration of the underlying psychiatric condition. The restlessness and agitation associated with akathisia may be mistakenly attributed to a worsening of the patient’s primary symptoms, leading to an increase in the dosage of neuroleptics that can aggravate akathisia symptoms, perpetuating a cycle of mismanagement and exacerbation.Reference Sienaert, van Harten and Rhebergen 4 In severe cases, akathisia has been linked to an increased risk of suicidal ideationReference Cheng, Park and Hernstadt 11 , Reference Seemüller, Lewitzka and Bauer 12 and aggression.Reference Keckich 13 –Reference Galynker and Nazarian 15

The primary approach to managing akathisia involves initial considerations for antipsychotic dose reduction, cessation of antipsychotic polypharmacy, and transitioning to an antipsychotic with a perceived lower risk of akathisia. The therapeutic options for akathisia are limited, and the evidence supporting commonly used pharmacological interventions, including switching to a less akathisia-prone antipsychotic or prescribing beta-blockers or antihistaminic/anticholinergic agents, remains constrained.Reference Pringsheim, Gardner and Addington 16

Aim

Lacking head-to-head comparisons and a meta-analysis of treatments for this condition, our research seeks to synthesize existing evidence, shedding light on the most effective pharmacological interventions for managing akathisia. The ultimate goal is to enhance the quality of care for individuals experiencing akathisia, improve treatment outcomes, and contribute to the advancement of neuropsychiatric practice.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt 17

Eligibility criteria

The primary objective of this review was to evaluate the efficacy of different therapies in addressing akathisia, specifically targeting non-immediate relief. To achieve this, our inclusion criteria encompassed studies conducted in both Italian and English languages. We focused on controlled trials involving human participants, with no restrictions on age or the origin of akathisia. We excluded cases of resistant akathisia.

Information sources

We searched three electronic databases: PubMed, Scopus, and EMBASE. The search was conducted up until July 9, 2023.

Search strategy

For the purpose of this study, we intentionally designed the search criteria to be as encompassing as possible. For our search on the PubMed platform, we used the following query: ((akathisia[Title/Abstract]) OR (akathisia, drug induced[MeSH Terms])) AND ((treatment[Title/Abstract]) OR (therapy[Title/Abstract])).

Within the SCOPUS database, we conducted our search with the search string: (akathisia) AND ((treatment) OR (therapy)).

In the EMBASE database, our query consisted of: (akathisia and (treatment or therapy)).tw.

Selection process

Screening by title and abstract was conducted by LG, DB, and GS independently. After title and abstract screening, full texts were retrieved for the remaining articles. Two authors (LG, and DB) reviewed the full texts against the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by referring to a third author (GS).

Data collection process

Four reviewers (LG, DB, GS, and LB) independently extracted data from the included studies. Disagreements were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached.

Data items

From the articles that met our inclusion criteria, we extracted the total number of participants involved in each study, the specific therapies employed within the studies, the specific amount of participants involved in each arm for every study, the origin of akathisia within the context of each study, and the posttreatment akathisia scores observed in the various arms of the studies.

Effect measures

The assessment of treatment effectiveness revolved around the evaluation of post-treatment akathisia scores and the effect size of each treatment as standardized mean difference (SMD). SMDs were calculated based on the final scores measured using the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale, Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Effects Rating Scale, and Extrapyramidal Symptoms Rating Scale, consistent with the scales employed in each respective study.

Synthesis methods

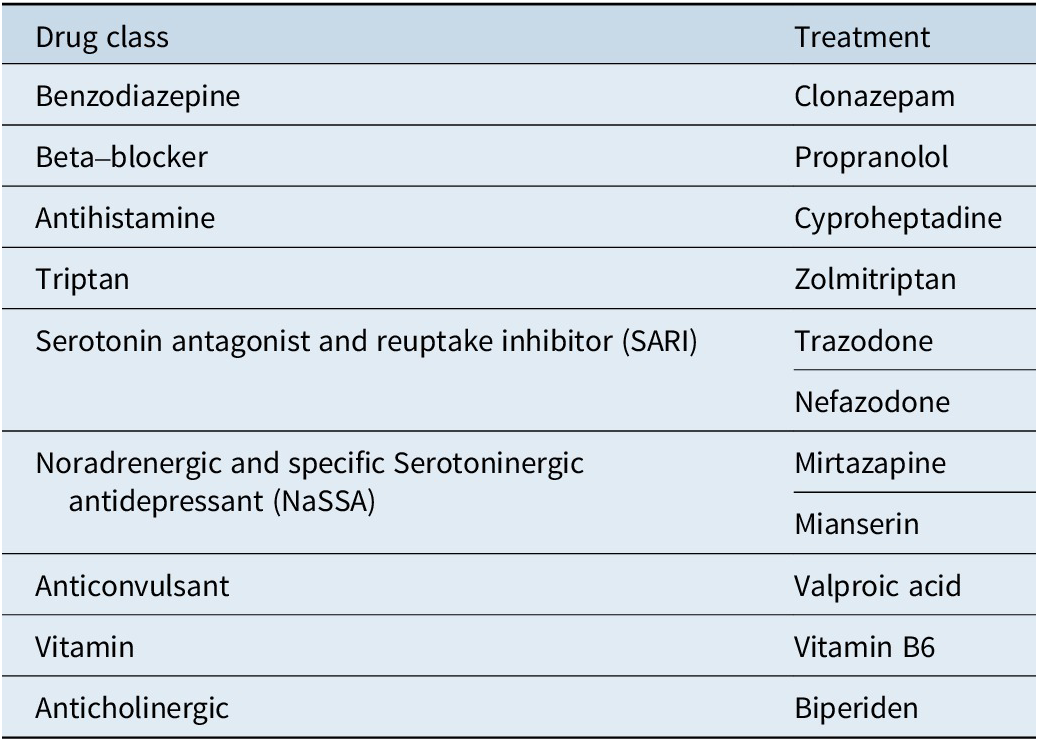

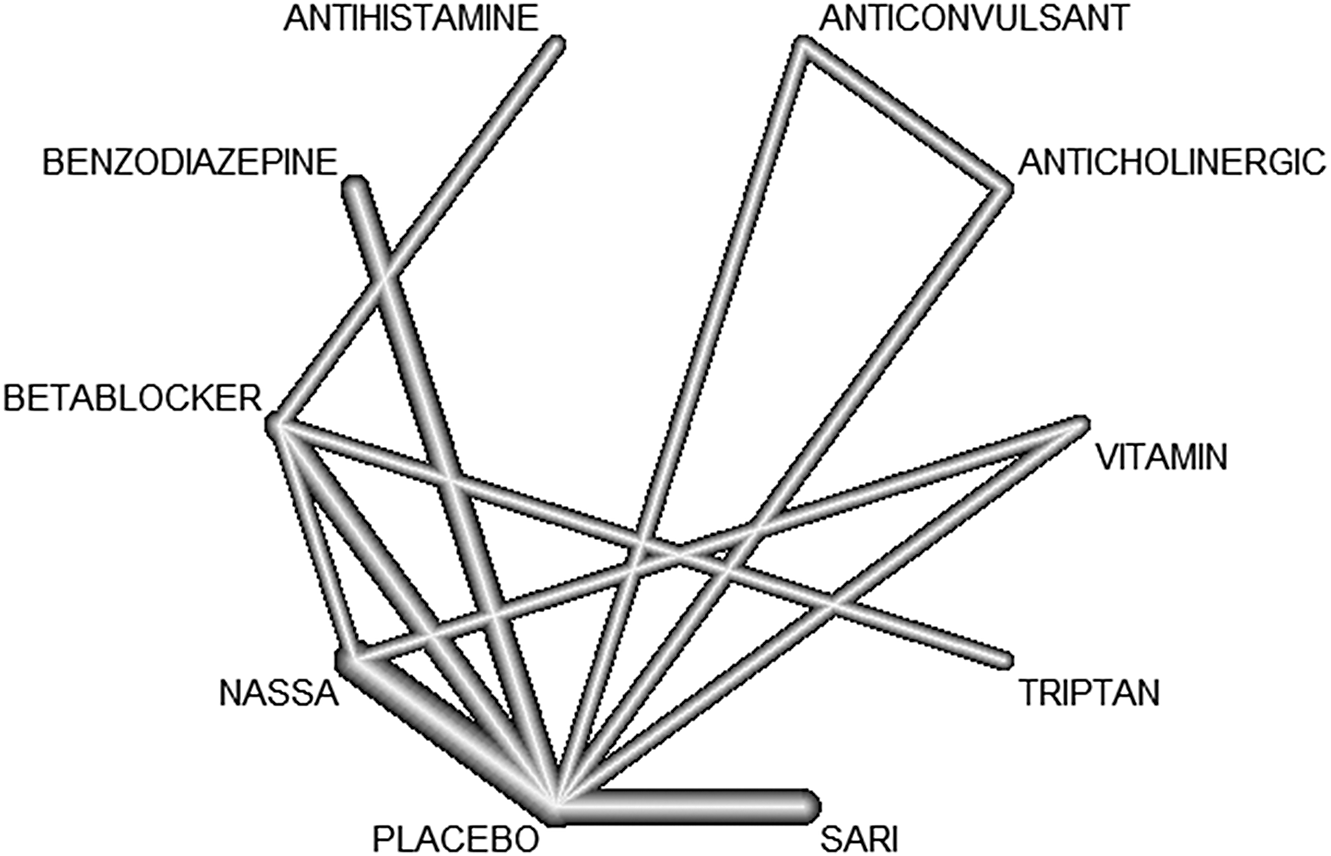

We summarized the results of all included studies and we grouped treatment by drug class. Table 1 displays drug classes and treatments and Figure 1 displays the corresponding network plot. We conducted a frequentist network meta-analysis with a random effect model of post-treatment SMDs of akathisia score. We also created forest plots and treatment rankings using P-score. Statistical analysis was performed with R “netmeta” package.Reference Balduzzi, Rücker and Nikolakopoulou 18

Table 1. Treatments Grouped by Drug Class

Figure 1. Network graph.

Study risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias assessment was conducted by DB using the Risk of Bias 2 (ROB2) tool.Reference Sterne, Savović and Page 19 The assessment is structured into a series of domains through which bias might be introduced into a trial. All domains are mandatory, and no further domains should be added.

Certainty assessment

We utilize the “netsplit” function within the netmeta package to assess inconsistency in network meta-analysis, specifically analyzing the significance of differences between direct and indirect comparisons of treatments.

Results

Study selection

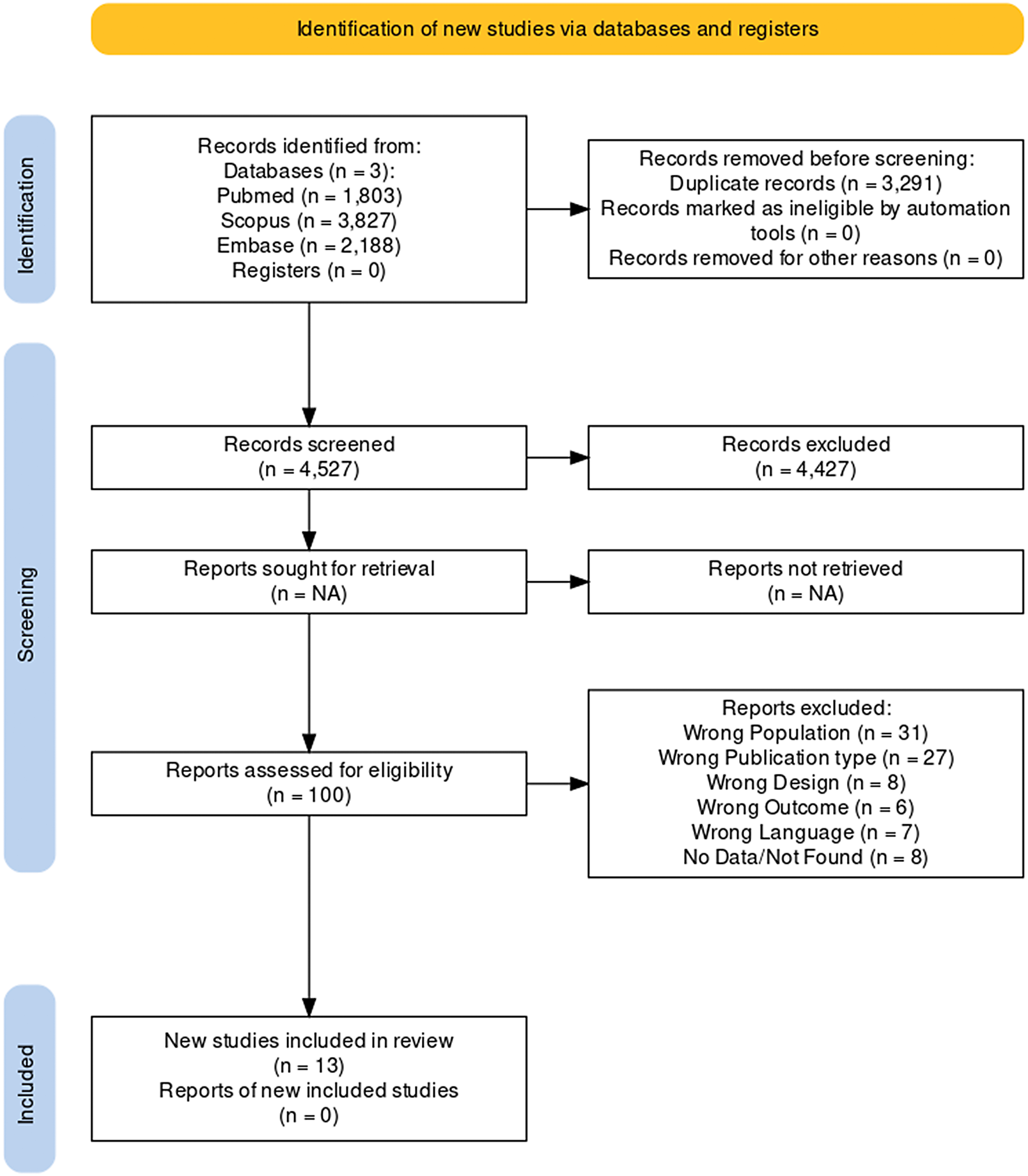

Initially, the search yielded 7818 papers, of which 3291 were duplicates. Title and abstract reading led to the exclusion of 4427 studies and full-text analysis to the elimination of 33 papers. A flow diagram of the literature searches and related screening processes is shown in Figure 2. A total of 13 studies published between 1983 and 2020 met our inclusion criteria,Reference Miodownik, Lerner and Statsenko20–Reference Poyurovsky, Pashinian and Weizman 32 for a total of 446 individuals.

Figure 2. PRISMA flowchart.

Study characteristics

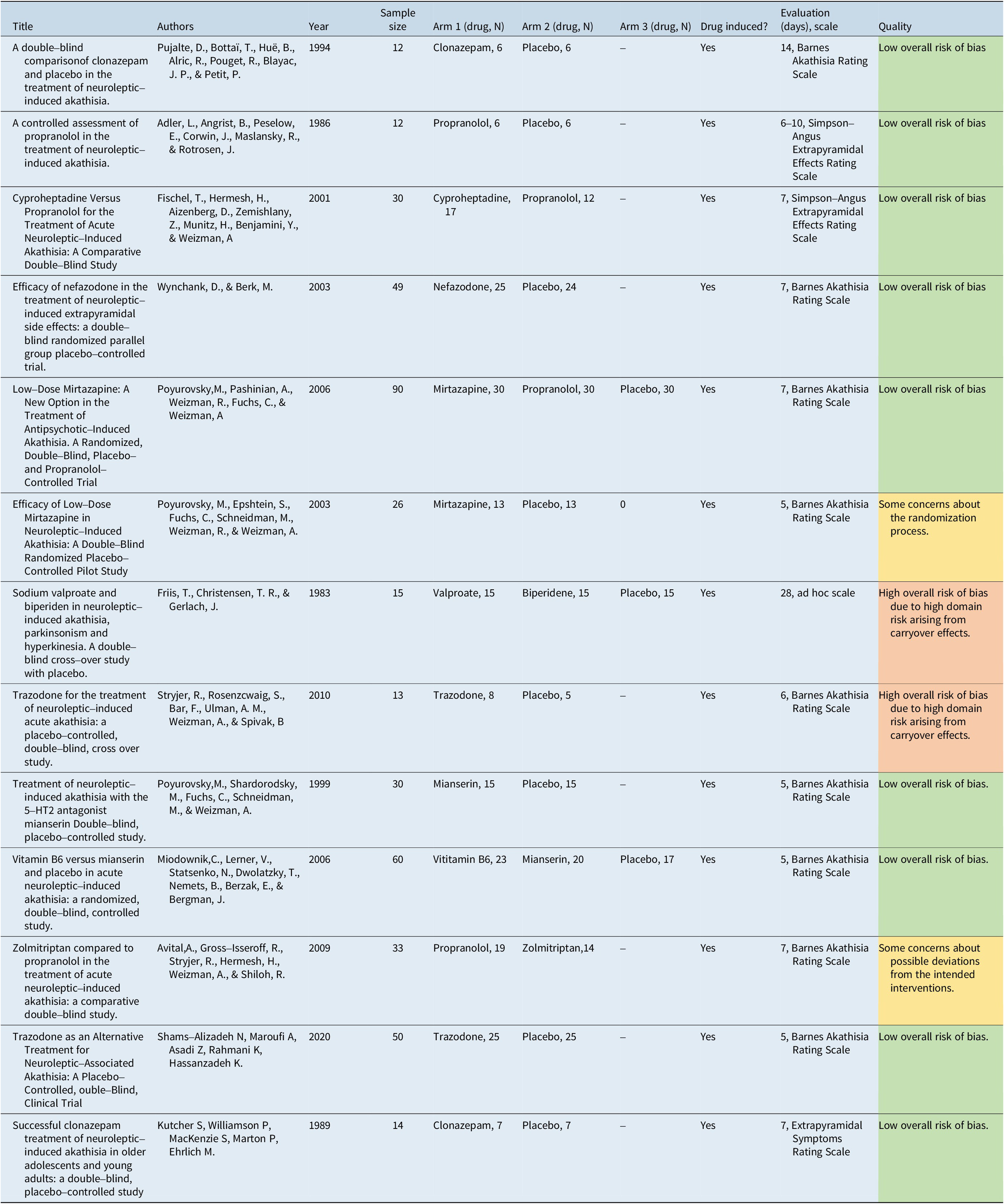

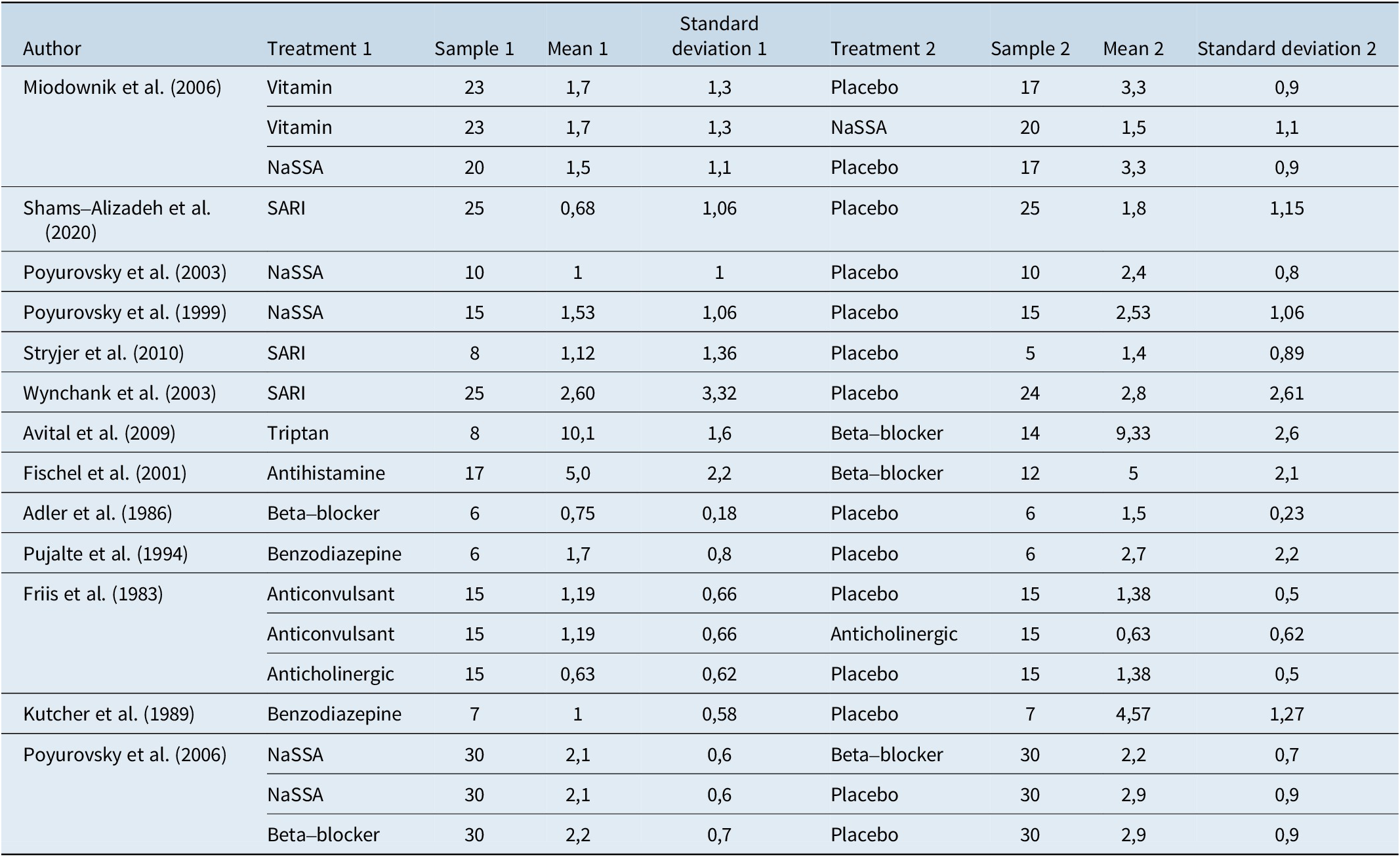

Table 2 provides a summary of the studies included in this analysis along with their generic data (eg, author, year, sample size) and treatments.

Table 2. Summary of Included Studies

Results of individual studies

Table 3 shows extracted data along with effect size and standard error from the 13 included studies.

Table 3. Extracted Data, Effect Size, and Standard Error

Results of syntheses

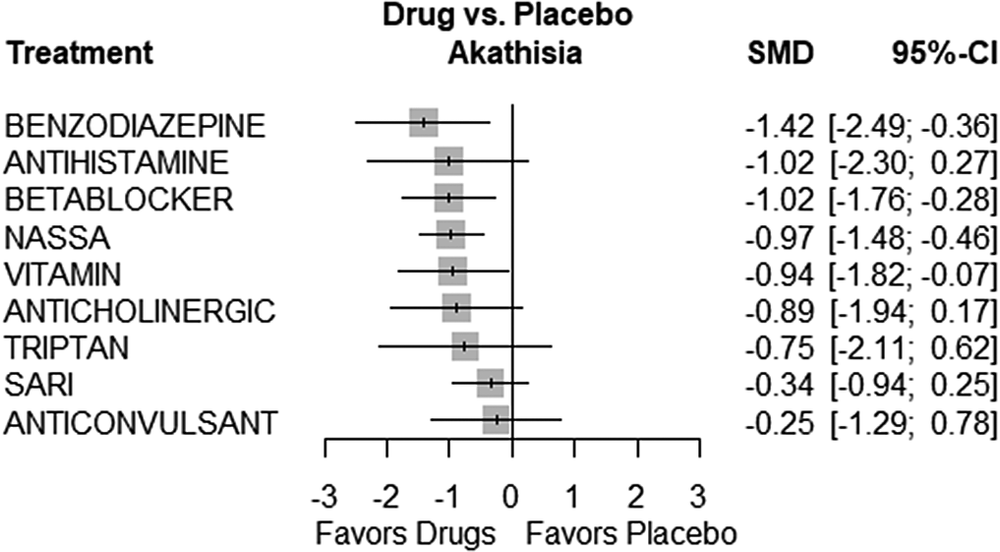

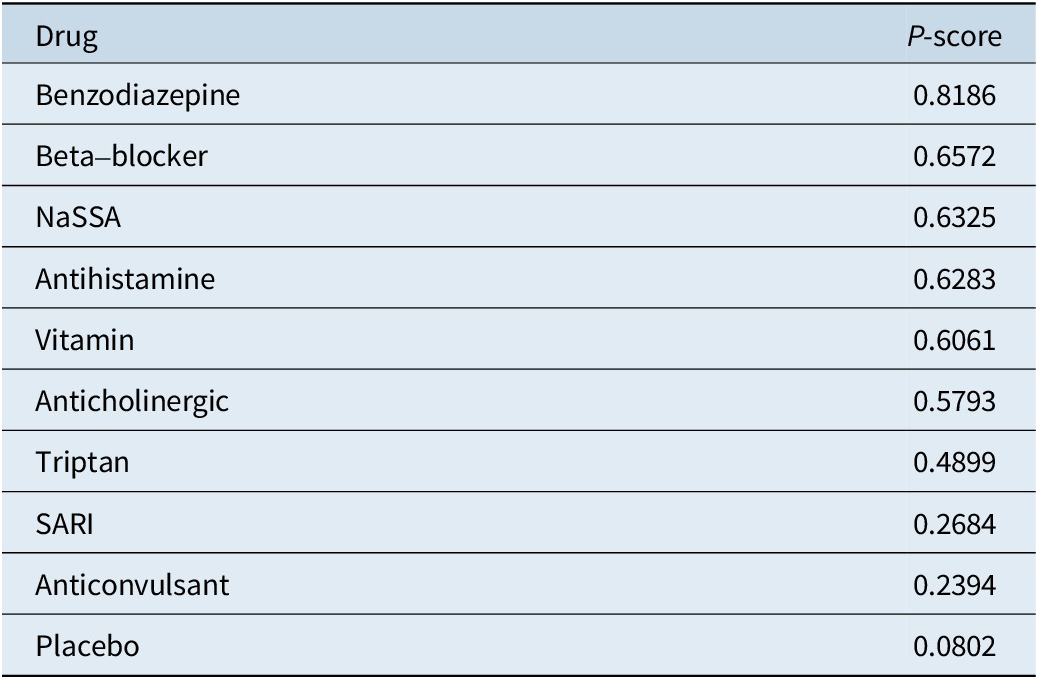

Several treatments showed statistically significant efficacy compared to placebo. These treatments included Benzodiazepines (SMD = −1.4217, 95% CI, −2.4852; −0.3581, P = 0.0088), Beta-blockers (SMD = −1.0156, 95% CI, −1.7557; −0.2755, P = 0.0072), and NaSSA (SMD = −0.9712, 95% CI, −1.4824; −0.4600, P = 0.0002). On the other hand, some treatments did not show statistically significant differences when compared to placebo. These treatments included Anticholinergic (SMD = −0.8851, 95% CI, −1.9448; 0.1746, P = 0.1016), Anticonvulsant (SMD = −0.2513, 95% CI, −1.2851; 0.7826, P = 0.6338), Antihistamine (SMD = −1.0156, 95% CI, −2.2990; 0.2678, P = 0.1209), SARI (SMD = −0.3449, 95% CI, −0.9382; 0.2484, P = 0.2545), Triptan (SMD = −0.7482, 95% CI, −2.1129; 0.6165, P = 0.2826), and Vitamin (SMD = −0.9438, 95% CI, −1.8194; −0.0683, P = 0.0346). Figure 3 presents the forest plot depicting the comparisons of various drugs with placebo. Table 4 displays the P-score rankings of the various treatments.

Figure 3. Forest plot.

Table 4. Rankings of the Treatments

In terms of heterogeneity, we observed moderate heterogeneity with an I^2 of 47.6%, indicating some variability in the treatment effects across the studies. However, the tests of heterogeneity within designs (Q = 7.99, p = 0.0918) and between designs (Q = 5.62, p = 0.1315) did not reach statistical significance, suggesting that the observed heterogeneity may not be significant.

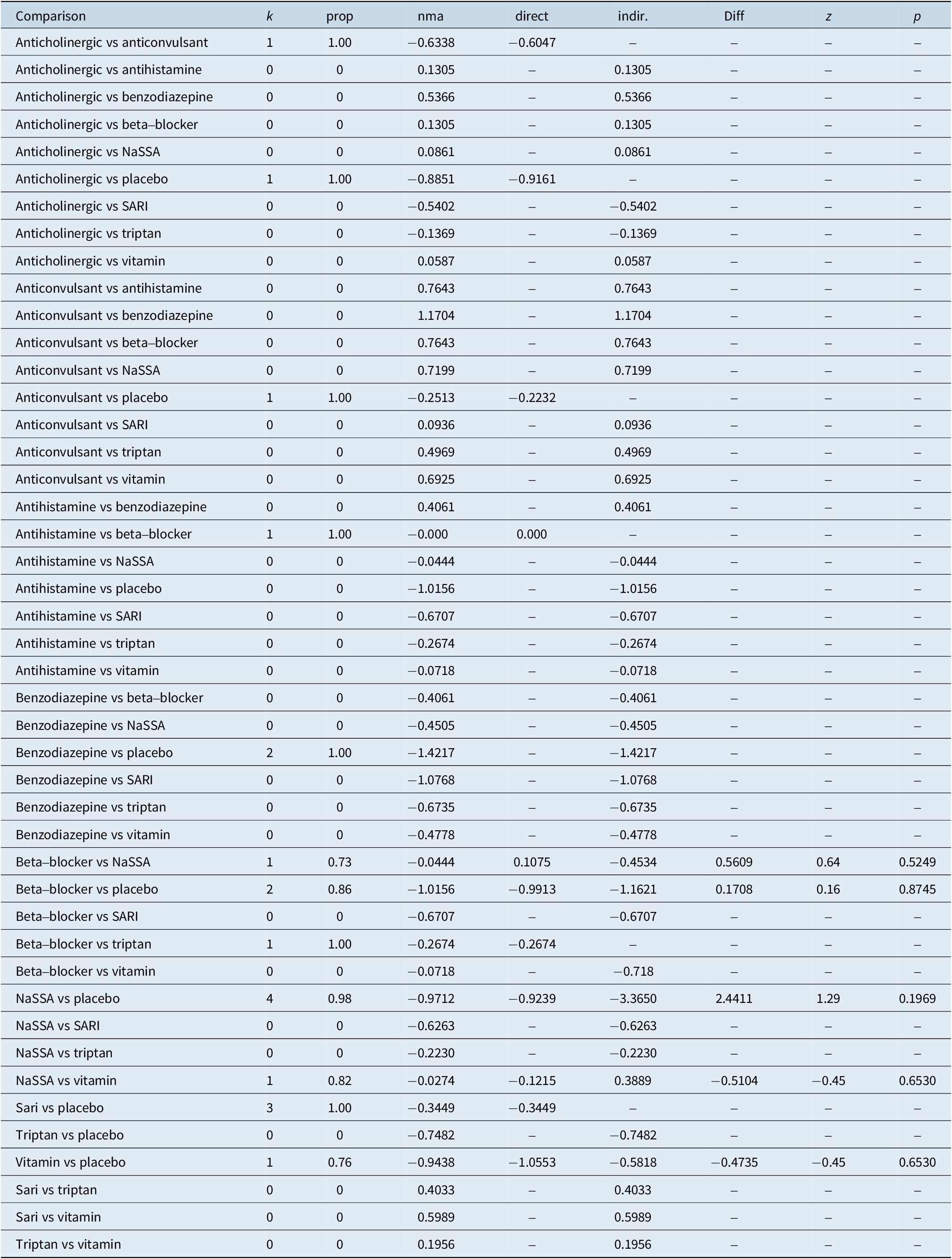

The results of the consistency analysis are presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Consistency Analysis

Legend:

comparison, treatment comparison

k, number of studies providing direct evidence

prop, direct evidence proportion

nma, estimated treatment effect (SMD) in network meta-analysis

direct, estimated treatment effect (SMD) derived from direct evidence

indir., estimated treatment effect (SMD) derived from indirect evidence

Diff, difference between direct and indirect treatment estimates

Z, z-value of test for disagreement (direct versus indirect)

P-value, p-value of test for disagreement (direct versus indirect)

Discussion

This research aimed to synthesize existing evidence to identify the most effective interventions for managing akathisia.

Despite the significance of this adverse effect, our review identified only 13 controlled trials of sufficient quality, and even more notably, merely 9 of them exhibited a low risk of bias. This scarcity of robust trials with low risk of bias makes it difficult to draw conclusions about the most effective treatment of akathisia, emphasizing the need for further well-designed and rigorous research in this critical area of study.

The results of the network meta-analysis revealed that benzodiazepines, beta-blockers, and NaSSA showed statistically significant efficacy compared to placebo, providing clinicians with evidence-based options for managing this distressing side effect. Conversely, some treatments, such as Anticholinergic, Anticonvulsant, and Triptan, did not demonstrate significant differences compared to placebo, indicating the need for further investigation or consideration of alternative approaches.

The results of the consistency analysis indicate that there is no statistically significant difference between direct and indirect comparisons, affirming the consistency and robustness of the synthesized evidence.

The P-score rankings presented in Table 4 provide additional insights into the relative effectiveness of these treatments. Benzodiazepines, with the highest P-score of 0.8186, appear to be the most promising intervention, followed by beta-blockers and NaSSA. These rankings can guide clinicians in selecting the most appropriate treatment options for individual patients based on the available evidence.

Conclusions

Akathisia remains a challenging and often overlooked side effect of psychotropic medications. This research contributes to the understanding of effective interventions for managing akathisia, with benzodiazepines, beta-blockers, and NaSSA showing significant promise. Effective management of akathisia is crucial not only to improve patient’s quality of life but also to prevent potential complications associated with non-adherence and mismanagement. Considering our current results, it may prove beneficial for future research to conduct controlled analyses specifically focused on the effects of benzodiazepines, beta-blockers, and NaSSA by comparing them directly with a placebo.

Limitations

The inclusion of small studies can contribute to increased heterogeneity and uncertainty in treatment rankings and estimates. Additionally, the susceptibility of small studies to publication bias underscores the need for caution in assessing the overall evidence. Therefore, while this research provides valuable insights, it is essential to consider the limitations imposed by low sample sizes and to prioritize future research efforts that involve larger, more robust studies to further our understanding of effective strategies for managing akathisia.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: L.G., G.S.; Data curation: L.G.; Formal analysis: L.G., L.B., G.S.; Investigation: L.G., D.B.; Methodology: L.G., L.B., G.S.; Project administration: L.G., G.S.; Resources: L.G., D.B.; Software: L.G.; Validation: L.G., L.B., G.S., M.D.; Visualization: L.G., M.D.; Writing – original draft: L.G., D.B.; Writing – review & editing: L.G., L.B., G.S., M.D.; Supervision: G.S.

Financial support

The study was conducted independently without any financial contributions from external sources.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests of any kind in relation to the research, data, or findings presented in this study.