We are frequently consulted by patients with treatment resistant depression (TRD).Reference Fogelson and Leuchter1 Many of these patients have never met criteria for a manic episode so they are not diagnosed with bipolar disorder (BPD). Consequently, they have undergone trials of antidepressants with or without augmentation therapies without success.Reference Perlis, Uher and Ostacher2 Antidepressants have caused increased agitation and anxietyReference Perlis, Smoller, Fava, Rosenbaum, Nierenberg and Sachs3, Reference Perugi, Pacchiarotti and Mainardi4 or have been ineffective. We believe that many of these patients would receive effective treatment if they were reconceptualized to be suffering from bipolar spectrum disorder (BPSD) and treated for bipolar depression. The diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD) with mixed featuresReference Koukopoulos and Sani5, Reference Suppes and Ostacher6 is not the same as a diagnosis of BPSD and will lead to too few patients reconceptualized as suffering from BPSD. We shall review the history and clinical characteristics of a patient with BPSD, only one of which (see Figure 1, item 8) refers to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM 5) criteria for a mixed state.

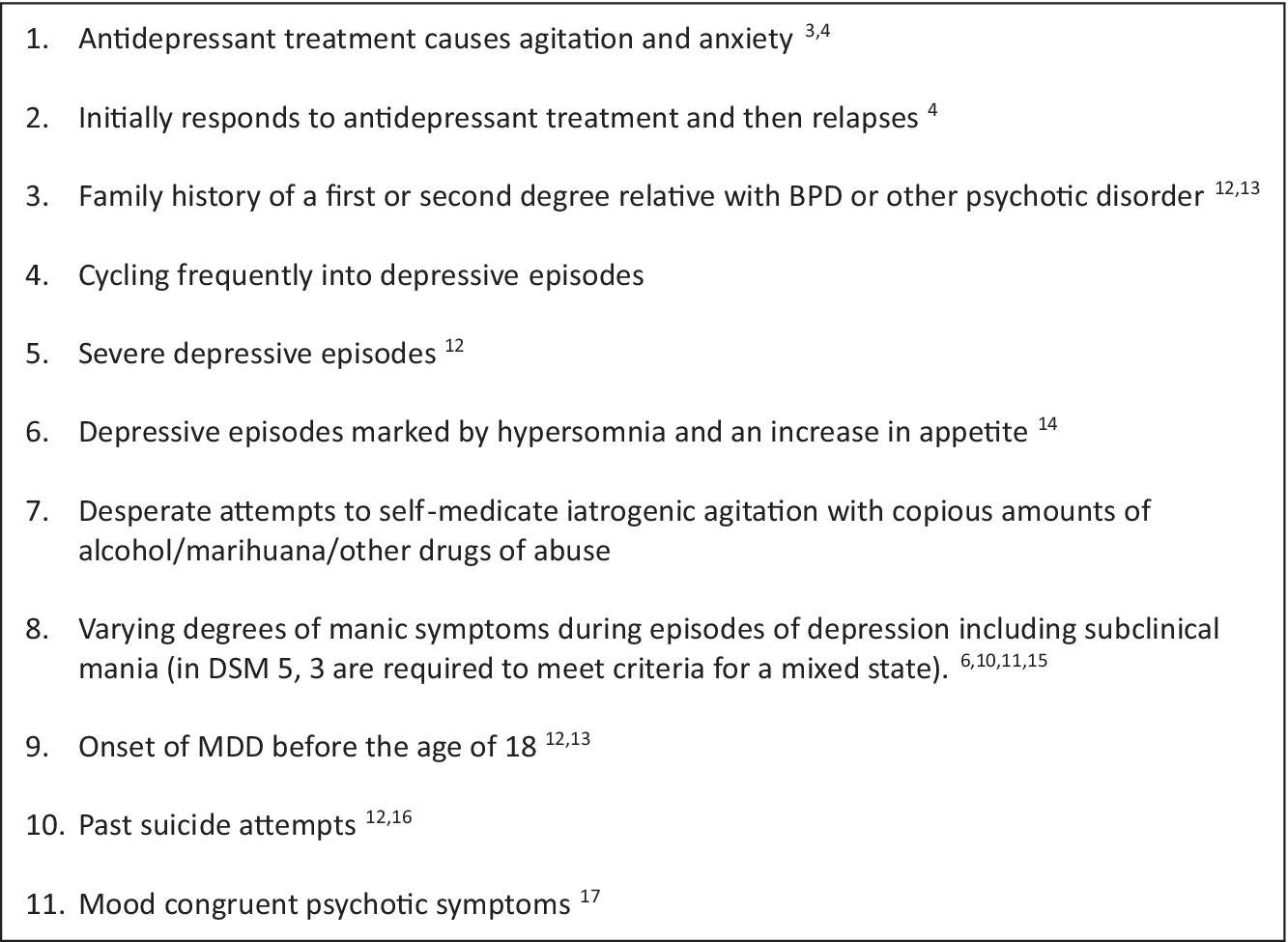

Figure 1. Clinical characteristics of a patient with treatment resistant depression who may suffer from bipolar spectrum disorder.

While most of clinical medicine has long used categorical diagnosis (ie, basing diagnosis on a patient meeting a standard list of criteria), psychiatry came late to the game, adopting categorical diagnosis with the DSM-III of 1980.Reference Mayes and Horwitz7 This change produced marked benefits in providing a common nomenclature for consensus diagnoses that did not depend on knowing the etiology of a disorder. Over time, however, research has shown psychiatric disorders in general, and BPD in particular, exist on a spectrum of illness that varies in terms of signs and symptoms. BPSD patients presenting with TRD will have varying manic symptoms consistent with a mixed state in addition to many other specific clinical features and/or a family history that set them apart from unipolar depression. In the early 1980s, Akiskal was one of the first clinicians to apply the spectrum concept to patients who did not meet full criteria for BPD but seemed to lie in between unipolar and bipolar patients.Reference Akiskal and Mallya8 A spectrum diagnosis should not be confused with a dimensional approach to diagnosis. A spectrum diagnosis does not posit that a diagnostic threshold is based upon a latent dimension, but rather upon the unique characteristics of each individual.Reference Kim, Keifer, Rodriguez-Seijas, Eaton, Lerner and Gadow9 This has been referred to as a hybrid model of diagnosis that integrates both categorical and dimensional representations of symptoms in that it acknowledges qualitative differences between individuals.Reference Kim, Keifer, Rodriguez-Seijas, Eaton, Lerner and Gadow9

A thorough review of MDD with mixed featuresReference Suppes and Ostacher6 presented evidence that not all patients with a degree of subthreshold mania went on to develop BPD.Reference Fiedorowicz, Endicott, Leon, Solomon, Keller and Coryell10, Reference Zimmermann, Brückl and Nocon11 This should not be taken as evidence that patients in mixed states with TRD, who will never have a manic episode, will not benefit from medications used to treat bipolar depression and discontinuation of antidepressants, especially if they present with additional clinical features presented in Figure 1. We caution the reader to note that the diagnosis of MDD with mixed featuresReference Koukopoulos and Sani5, Reference Suppes and Ostacher6 is a subset of the diagnosis of BPSD. Limiting BPSD to patients who meet criteria for MDD with mixed features will lead to too few patients suffering from treatment resistant depression reconceptualized as suffering from BPSD.

We identify patients with TRD as suffering from a BPSD, using a structured clinical interview to retrospectively ascertain their illness history. We systematically inquire about signs and symptoms that contribute to a diagnosis of MDD with BPSD features (see Figure 1), including: antidepressants having caused them to feel more agitated and anxiousReference Perlis, Smoller, Fava, Rosenbaum, Nierenberg and Sachs3, Reference Perugi, Pacchiarotti and Mainardi4 not less so; initially responding to antidepressants only to relapseReference Perugi, Pacchiarotti and Mainardi4; having a first or second degree relative with BPD or other psychotic disorderReference Perlis, Brown, Baker and Nierenberg12, Reference Angst, Azorin and Bowden13; cycling frequently into depressive episodes; having severe depressive episodesReference Perlis, Brown, Baker and Nierenberg12; having depressive episodes marked by hypersomnia and an increase in appetiteReference Mitchell, Wilhelm, Parker, Austin, Rutgers and Malhi14; having made desperate attempts to self-medicate their iatrogenic agitation with copious amounts of alcohol/marihuana; having varying degrees of manic symptoms during their episodes of depressionReference Angst, Merikangas, Cui, Van Meter, Ajdacic-Gross and Rossler15; having an onset of MDD before the age of 18Reference Perlis, Brown, Baker and Nierenberg12, Reference Angst, Azorin and Bowden13; having made past suicide attemptsReference Perlis, Brown, Baker and Nierenberg12, Reference Olfson, Das and Gameroff16; and having mood congruent psychotic symptoms.Reference Mitchell, Frankland and Hadzi-Pavlovic17 Any one of these signs and symptoms associated with TRD alert us to the possibility that the patient has BPSD.

There is scant evidence supporting the effectiveness of treatments for TRD with BPSD features. One placebo controlled double blind trial of patients with MDD and a mixed state demonstrated lurasidone to be an effective treatment.Reference Suppes, Silva and Cucchiaro18 A systematic review of treatments for MDD with mixed features found that there was little evidence for efficacy for other pharmacological treatments.Reference Shim, Bahk, Woo and Yoon19

Given the poor evidence base, we do not believe that BPSD patients with TRD should only be treated with lurasidone. We believe patients with TRD and BPSD features should be taken off antidepressants and treated with a mood stabilizer proven to be effective in bipolar depression, including lithium,Reference Sani and Fiorillo20 lamotrigine, olanzapine with or without fluoxetine, quetiapine, lurasidone, or cariprazine.Reference Post21 Patients will often respond or remit to this approach when they have not responded to treatment with antidepressants.Reference Perlis, Uher and Ostacher2 When all else fails, we consider clozapine for its effectiveness in treatment-resistant BPD and for its antisuicidal properties.Reference Khokhar, Henricks, Sullivan and Green22 For a thorough review of treatment options for mixed depression, which we believe apply to BPSD treatment, please see the guideline published in CNS Spectrums.Reference Stahl, Morrissette and Faedda23 Unlike our recommendations, this guideline includes treatments that have not been Food and Drug Administration of the United States of America (FDA) approved for the treatment of bipolar depression.

Here is a clinical case example of BPSD:

A 60-year-old businessman presented to the emergency room with a panic attack. He had been treated with escitalopram 5 mg per day and lorazepam 1 mg three times per day. He was diagnosed with MDD with mood congruent psychotic features (somatic delusions) and Generalized anxiety Disorder. Rating scales demonstrated that he had moderate depression and severe anxiety. He had no history of a manic episode. His brother had been diagnosed with Bipolar 2 disorder. His escitalopram was discontinued, and he was treated with fluoxetine 40 mg per day for 1 month. His depression progressively became worse and his anxiety minimally improved. Bupropion, 300 mg per day was added without improvement in his depression and with almost immediate worsening of his anxiety.

His diagnosis was changed to TRD with BPSD features. His BPSD features included an antidepressant exacerbating his anxiety, family history of BPD, depression with psychotic features, and depression becoming severe while treated with antidepressants. Bupropion and fluoxetine were discontinued, and lithium therapy started. After 4 weeks on lithium therapy he was in full remission of his depression and anxiety symptoms and has remained so for 6 months.

Our approach is informed by the consensus that bipolar depression has not consistently been demonstrated to respond to antidepressant medications or to the addition of an antidepressant to a mood stabilizer medication with the one exception of fluoxetine combined with olanzapine, but rather to monotherapy with mood stabilizers.Reference Ghaemi, Ko and Goodwin24, Reference Pacchiarotti, Bond and Baldessarini25 Furthermore, there is growing evidence that antidepressants actually make things worse.Reference Perugi, Pacchiarotti and Mainardi4 There may be a subset of BPSD patients, 15%, who do best with a combination of a mood stabilizer and antidepressant,Reference Goodwin, Haddad and Ferrier26 but we find they are the exception, not the rule.

If a diagnosis of BPSD can be made early, much suffering will be averted. It is a difficult paradigm shift to stop antidepressants in a patient with categorical “unipolar” depression. The physician can be so wedded to a categorical diagnosis that the patient never receives appropriate care. It is less difficult to stop antidepressants, if the clinician considers the mounting evidence that makes it increasingly unlikely that mental disorders are categorical diagnoses, but rather lie on a spectrum of mental disorders. Where on the spectrum, a particular patient’s illness is found, determines what treatments will be successful, not their categorical diagnosis.

Genetic advances and imaging studies support the concept of BPSD. The Psychiatric Genomics Consortium has demonstrated that MDD and BPD are polygenic disorders.Reference Sullivan and Geschwind27 The single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that contribute to MDD overlap with those that contribute to BPD.Reference Anttila, Bulik-Sullivan and Finucane28 Given that it has been established that at least 53 SNPs contribute to the polygenic risk score (PRS) for BPD and that the risk for BPDReference Ruderfer, Ripke and McQuillin29 and its severity increases as a patient has more of these SNPs,Reference Mistry, Harrison, Smith, Escott-Price and Zammit30 there are literally hundreds of possible unique genetic presentations of BPSD and BPD. Now combine each of these unique presentations with all possible combinations of non-BPD genes, combined with environmental exposures over the years from infection, malnutrition, in utero trauma, immune factors, and childhood adversity, and you begin to understand the nearly infinite variety of clinical presentations of BPSD and BPD that are possible. Characterizing patients by their unique PRS will allow us greater precision in assigning a phenotype (psychiatric syndrome),Reference Musliner, Krebs, Albiñana, Vilhjalmsson, Agerbo, Zandi, Hougaard, Nordentoft, Børglum, Werge, Mortensen and Østergaard31 selecting treatments and predicting treatment outcome.

Imaging studies have demonstrated that BPD is heterogenous at the level of brain physiology; there is not one abnormal state in BPDs but rather many, supporting the concept of a bipolar spectrum. At the level of the individual with BPD, deviations from normal patients are frequent but highly heterogeneous. Overlap of abnormal imaging of more than 2% among patients is observed in only a few brain areas, primarily in frontal, temporal, and cerebellar regions. Each patient’s unique brain physiology is associated with diagnosis and cognitive and clinical characteristics within their clinical diagnosis.Reference Wolfers, Doan and Kaufmann32 Several other biomarkers have been suggested for BPD and may 1 day be useful for identifying patients with BPSD.Reference Sigitova, Fisar, Hroudova, Cikankova and Raboch33

If we can determine that a patient has a high BPD PRS as well as brain imaging and other biomarkers consistent with BPD, we may be able to begin treatment with mood stabilizers at their first visit and spare them years of disability caused by inappropriate pharmacotherapy. Until biomarkers are readily available in the clinic, there is an urgency to establish algorithms of signs and symptoms of BPSD that will allow clinicians to more quickly and accurately select effective treatments.

While future advances in genetics and biomarker research hold out the promise of more accurate diagnosis and treatment in coming years, for now, clinicians would be well advised to consider the clinical characteristics listed in Figure 1 when treating a patient with depression. This becomes even more important when “treatment resistant” depression is encountered. For now, we must employ our clinical acumen until the promised days of precision medicine arrive.

Disclosures

David Fogelson and Bruce Kagan have no conflicts of interest and this work was not supported by any grants or honoraria.