No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

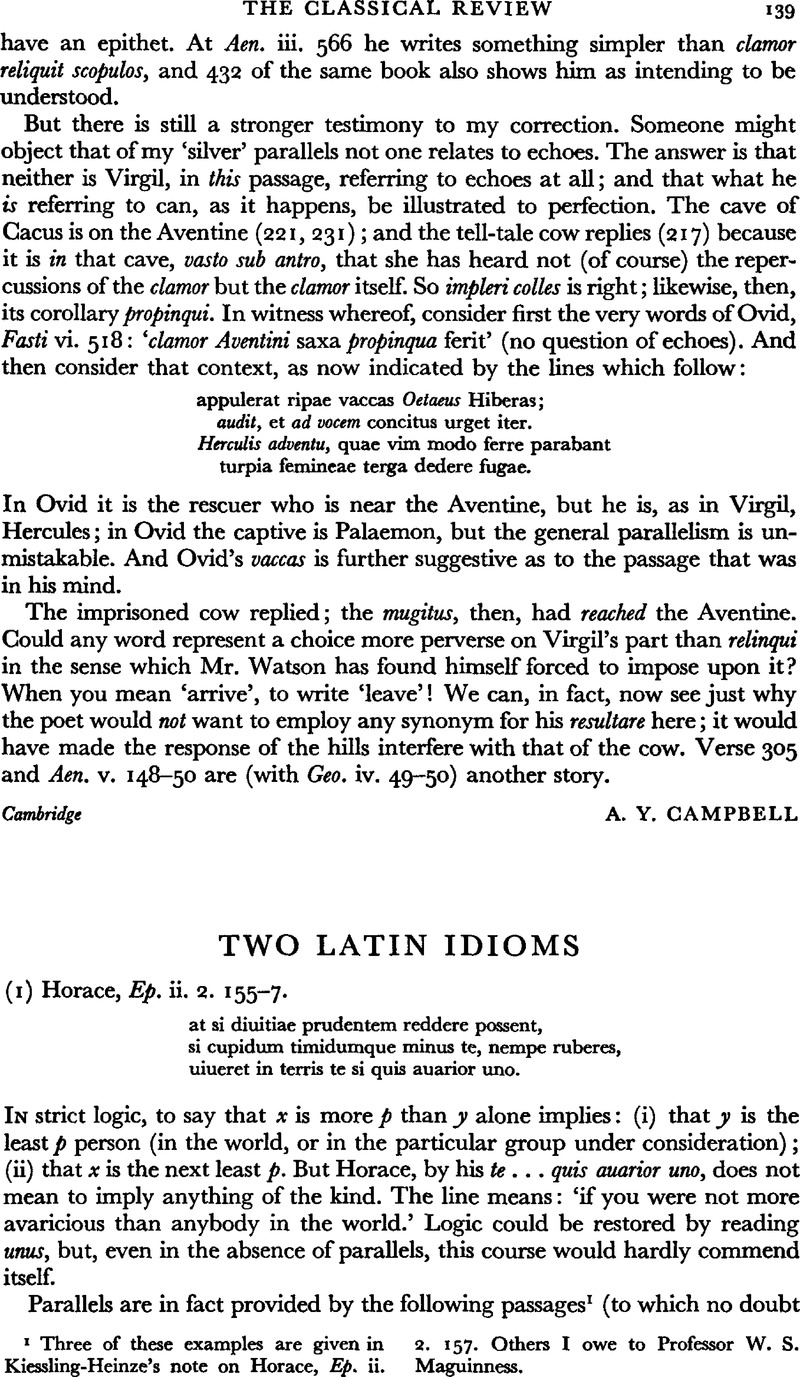

Two Latin Idioms

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1955

References

page 139 note 1 Three of these examples are given in Kiessling-Heinze's note on Horace, Ep. ii.

page 139 note 2 157. Others I owe to Professor W. S. Maguinness.

page 140 note 1 And this is how it is explained by Kiessling-Heinze, ad loc.: ‘uno ist wohl so zu erklären, dass der Satz ursprünglich negative gedacht war, nisi tu unus avarissimus omnium esses; bei der Umformung blieb das tu unus erhalten.’ The parallels follow, but the difference between the negative and positive examples of the idiom is not brought out.

page 141 note 1 A sarcastic intention is here probable (as at Martial xii. 87. 2 f., where turba mean a household of slaves). It should be noted, however, that the turba of Propertius, iv. 11. 76 consists of three children only. (At 98 in the same poem caterua is presumably a variant on this idiomatic use of turba.)

page 141 note 2 Other Ovidian instances: ex Pont. ii. 2. 97 ff.; Met. v. 303 and xiii. 743; Her. 9. 51.

page 141 note 3 Cf. ii. 32. 37.

page 141 note 4 This, and several of the other instances were brought to my attention by Miss Edna Jenkinson.