No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

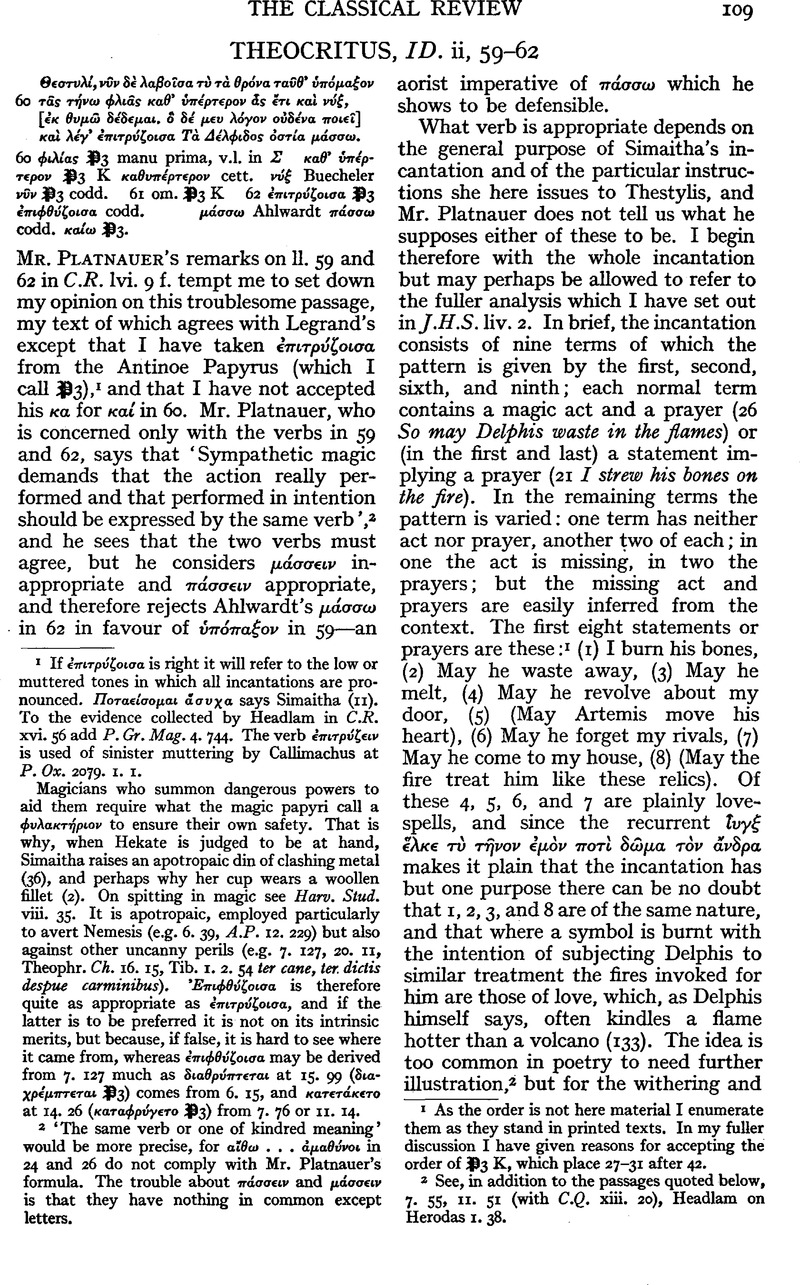

page 109 note 1 If ⋯πιτρ⋯ζοισα is right it will refer to the low or muttered tones in which all incantations are pronounced. Ποταɛ⋯σομαι ἄσυχα says Simaitha (II). To the evidence collected by Headlam in C.R. xvi. 56 add P. Gr. Mag. 4. 744. The verb ⋯πιτρ⋯ζɛιν is used of sinister muttering by Callimachus at P. Ox. 2079. 1. 1.

Magicians who summon dangerous powers to aid them require what the magic papyri call a φυλακτ⋯ριον to ensure their own safety. That why, when Hekate is judged to be at hand, Simaitha raises an apotropaic din of clashing metal (36), and perhaps why her cup wears a woollen fillet (2). On spitting in magic see Harv. Stud. viii. 35. It is apotropaic, employed particularly to avert Nemesis (e.g. 6. 39, A.P. 12. 229) but also against other uncanny perils (e.g. 7. 127, 20. II, Theophr. Ch. 16. 15, Tib. 1. 2. 54 ter cane, ter. dictis despue carminibus). Ἐπιφθ⋯ζοισα is therefore quite as appropriate as ⋯πιτρ⋯ζοισα, and if the latter is to be preferred it is not on its intrinsic merits, but because, if false, it is hard to see where it came from, whereas ⋯πιφθ⋯ζοισα may be derived from 7. 127 much as διαθρὑπτɛται at 15. 99 (διαχ⋯μπτɛται ![]() ) comes from 6. 15, and

) comes from 6. 15, and ![]() at 14. 26 (

at 14. 26 (![]() ) from 7. 76 or II. 14.

) from 7. 76 or II. 14.

page 109 note 2 ‘The same verb or one of kindred meaning7rsquo; would be more precise, for αἴθω…⋯μαθ⋯νοι in 24 and26 do not comply with Mr. Platnauer's formula. The trouble about π⋯σσɛιν and μ⋯σσɛιν is that they have nothing in common except letters.

page 109 note 1 As the order is not here material I enumerate them as they stand in printed texts. In my fuller discussion I have given reasons for accepting the order of ![]() , which place 27–31 after 42.

, which place 27–31 after 42.

page 109 2 See, in addition to the passages quoted below, 7. 55, 11. 51 (with C.Q. xiii. 20), Headlam on Herodas 1. 38.

page 110 note 1 Simaitha's word καταδɛἶν (3,10,159) is colourless, and appropriate to any magical constraint. κατ⋯δɛσμος and φιλτροκατ⋯δɛσμος are used of lovecharms (P. Gr. Mag. 4. 296, 395), but the more precise word in the papyri is ⋯γωγ⋯.

page 110 note 2 For further illustrations see Schweitzer, H., Aberglaube u. Zauberei bei T. (Basel, 1937), 43.Google Scholar

page 110 note 3 There is of course an element of the vindictive in Simaitha's passion, and it is possible that at 160 she really contemplates murder. The κακ⋯ν ποτ⋯ν of 58, however, as Ihave said elsewhere (C.R. lii. 144), I take to be a potent philtre which, if it does not cure, may kill.

page 110 note 1 I do not understand Mr. Platnauer's objection that knead is not the right verb for θρ⋯να or for ⋯στἰα. If it is right for bones then it is right for whatever represents them. ᎘ρ⋯να means, and is regularly glossed, φ⋯ρμακα, and that is what Simaitha calls all the materials with which she is operating (15). Add to L. and S.'s references for this sense of θρ⋯να Nic. Th. 99, Al. 155.

page 110 note 2 Textgeschichte, 258; Hermes, lxiii. 375.

page 110 note 3 If καí is to be pressed it will mean‘while darkness, as well as other favourable circumstances, is present’: but ěτι In is elsewhere followed by an almost superfluous καí. I will not cite 159 (where κ⋯ μɛ λυπῇ should no doubt be read): but see 8. 23, Il. 2. 229,19. 70.

page 111 note 1 Ancient superstitions concerning doorways are collected by M. B. Ogle in A.J.P. xxxii. 251.

page 111 note 2 Zur Erkläarung d. Idyllen Theokrits (Rostock u. Leipzig, 1792), 117.

page 111 note 3 Μ⋯σσɛιν means to knead, work with the hands, and so δια-, ⋯μμ⋯σσɛιν. The two last have also senses like those of the ⋯πο-, ⋯κ-, πɛρι-, προσ-, compounds, where the idea is rather of wiping or taking an impression. I do not think, however, that smear is an impossible meaning for ὐπομ⋯σσɛιν. Mr. Platnauer, by the way, should notsay that this compound does not occur, for it appears in an obscure and anonymous citation in Suidas, s.v. ὑπομɛμαγμ⋯νη), where it is glossed, apparently from some second passage, ⋯ναπɛφυρμ⋯νη. The exact force of the preposition I will not attempt to determine.

page 111 note 1 Plin. N.H. 28. 86, 117. In T. the θρ⋯να are surrogates for the bones of Delphis, not, as here, materials in themselves noxious. Therefore I do not think the θρ⋯να need come into contact with the door. The important point is the kneading, and what Thestylis will leave in the doorway will be the influence resulting from that operation. The interpretation of καθ ὑπ⋯ρτɛρον, however, is a minor point.

2 Textgeschichte, 58.

page 112 note 1 Hence no doubt the origin of π⋯σσω in 62: it comes from 21. Ωα⋯ω of ![]() is pretty plainly due to κα⋯ ν⋯ν at the end of the previous lineand is no foundation for the emendation which Dr. Schweitzer has built upon it.

is pretty plainly due to κα⋯ ν⋯ν at the end of the previous lineand is no foundation for the emendation which Dr. Schweitzer has built upon it.