No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

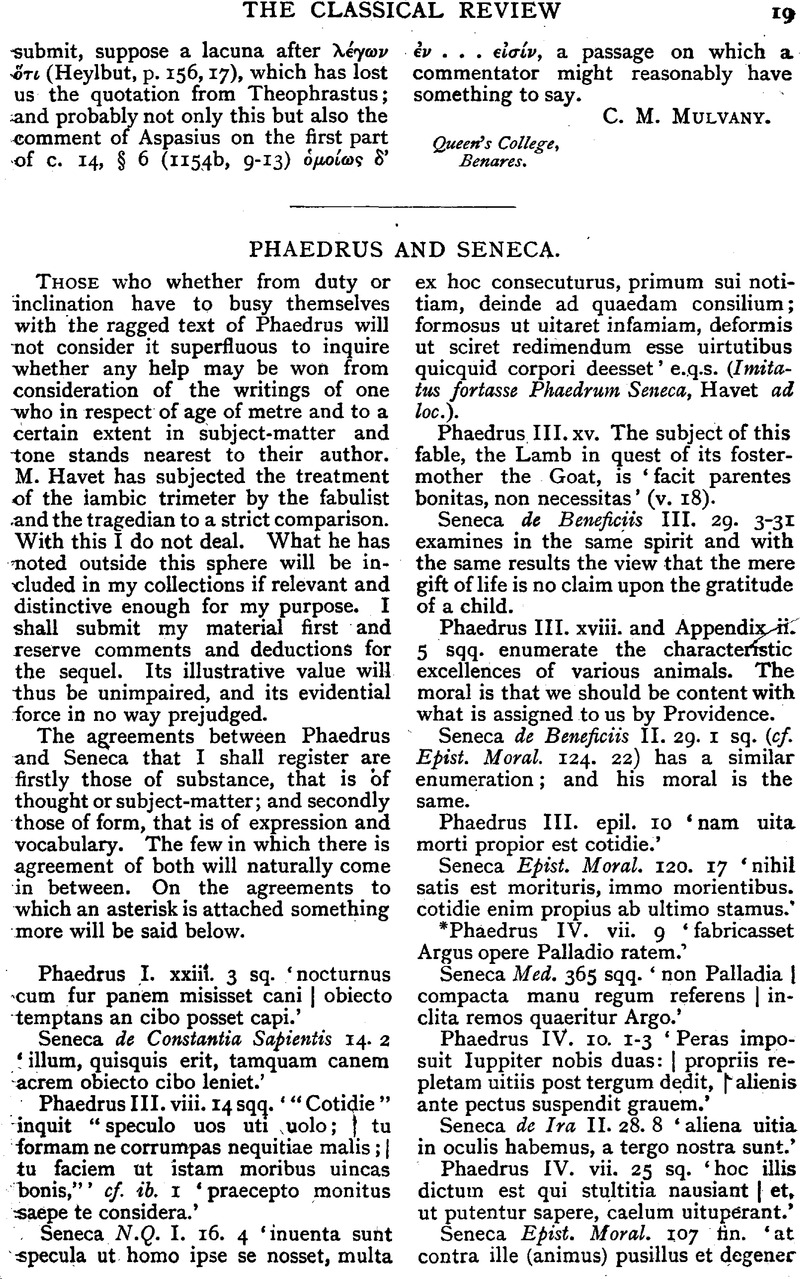

Phaedrus and Seneca

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Original Contributions

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1919

References

page 22 note 1 iocus with its congeners occurs some eleven times, improbus (with improbitas) some seventeen times in the extant Fables.

page 23 note 1 No argument can be based on the use of the common instead of the proper name. The use is both natural (cf. ⋯ ποιητ⋯ς in Greek) and appropriate. Phaedrus himself called his fables Aesopiac, and as only a selection from them would be included in the school anthology, there was no special call to give his name.

page 23 note 2 There is little in the idioms or diction of Phaedrus to suggest the foreigner. His use of abstract nouns is certainly pushed beyond the Latin norm. Of mehercules in the mouth of Minerva, III. xvii. 8, M. Havet writes with reason satis mira uox in ore et femineo et diuino, Gell. XI. 8. 3 (Gellius says it is not so used ‘apud idoneos quidem scriptores,’ but he might perhaps have excused it from an undoubted virago). Gruis tor grus I. i. 7 offends us more. It would certainly have made Priscian ‘gasp’; cf. Neue-Wagener Formenlehre I. p. 278. One is sorely tempted to suggest ‘tandem persuasumst iure iurando grui.’

page 23 note 3 The questions arising out of the passage of Seneca have been carefully and soberly discussed in W. Isleib's de Senecae Dialogo Vndecimo, a Marburg degree dissertation of 1906.