No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

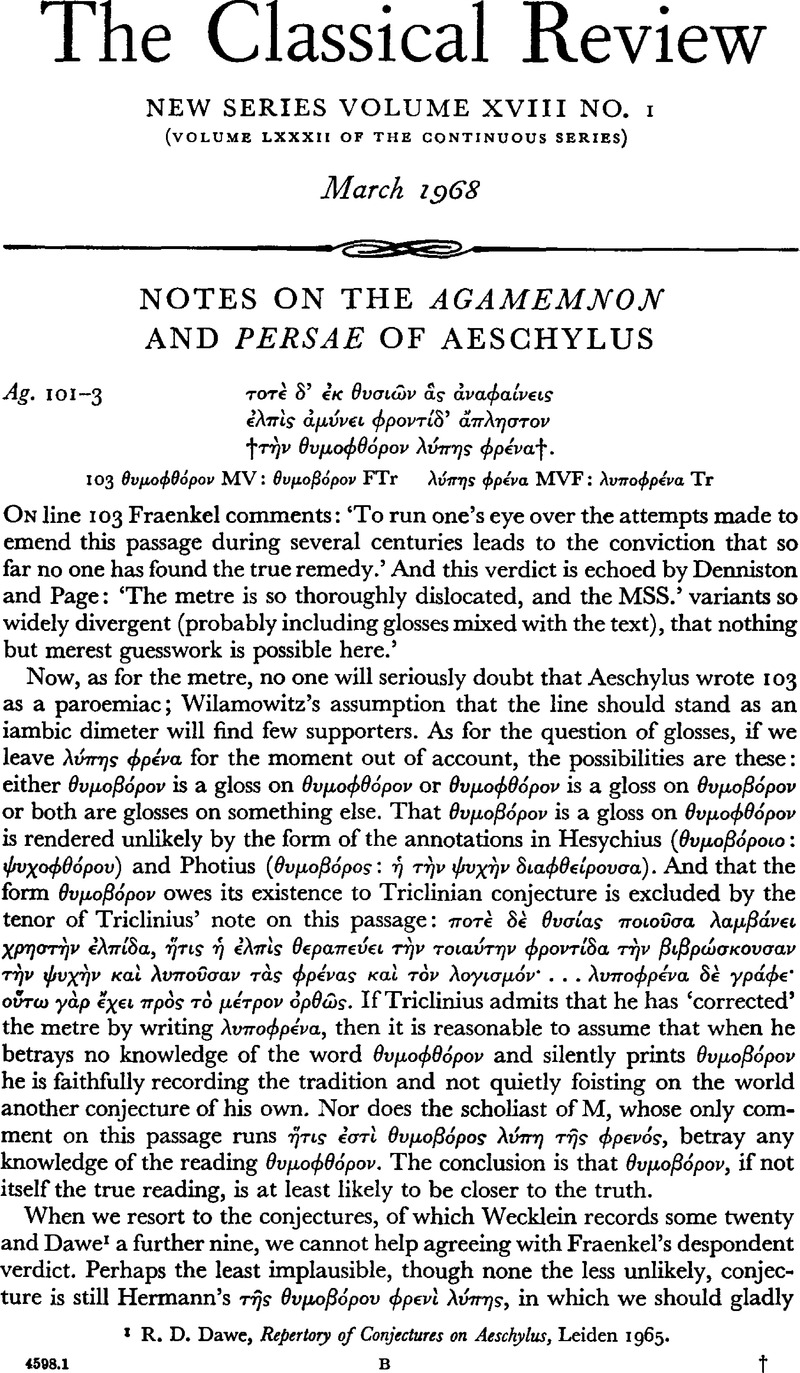

Notes on the Agamemnon and Persae of Aeschylus

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1968

References

page 1 note 1 Dawe, R. D., Repertory of Conjectures on Aeschylus, Leiden 1965.Google Scholar

page 2 note 1 See C.Q. xxiv (1940), 60.Google Scholar

page 2 note 2 The conjecture and construction are defended at length by Ferrari, W., Annali della R. Scuola Norm. Sup. di Pisa, lettere, storia e filos., vii. 2 (1938), 363–366.Google Scholar

page 2 note 4 For this form of paroemiac cf. Parker, L., C.Q.. xlii (1958), 84.Google Scholar

page 2 note 5 It is pleasing to discover from Wecklein that this verb had occurred also to Bamberger, who suggested φροντ⋯δ' ἄπληοτον/λ⋯της, φρ⋯να θυμοβορ⋯σαν, which however is unstylish and syntactically ambiguous. As Hermann saw, ‘requiritur genetivus ad ἄπληστον’.

page 2 note 6 But, as Professor D. L. Page has suggested to me, we ought to allow for the inversion of λ⋯πης φρ⋯να and admit into consideration θυμοβορο⋯σης φρ⋯nu;α λ⋯πης.

page 3 note 1 Lest it be objected that classical Greek furnishes no examples of true compounds from the noun κοῖτος/κο⋯τη (or even λ⋯χος and λ⋯κτρον), it should be noted that our only examples of a compound from the noun δ⋯μνιον are the two occurrences of the exactly analogous form δεμνιοτ⋯ρης in this very play.

page 3 note 2 The confusion of K with IC scarcely needs illustration, but I give three certain instances in the Oresteia: Cho. 897 ᾧ συ Robortello: ὠκ⋯ Μ, Eum. 177 εἶσιν οὗ Kirchhoff: ⋯κε⋯νου codd., 862 ἱδρ⋯σῃς Ἄρη Stephanus: ἱδρ⋯σῃ κ⋯ρα codd.

page 3 note 3 For further examples of this type see Jackson, John, Marginalia Scaenica, p. 106.Google Scholar

page 4 note 1 I have not had access to the dissertation by Kühn, W., De Vocum Sonorumque in Strophicis Aeschyli Canticis Acquabilitate (Halle, 1905), mentioned by Kranz, p. 298.Google Scholar

page 4 note 2 Murray prints ἔχουσιν … μ⋯νουσι, heedless of the warning of Kranz (p. 299), ‘um des Gleichklangs willen muss man Hept. 911 f. ἔχουσι und μ⋯νουσι entweder beide mit -ν schreiben oder keins von beiden’.

page 4 note 3 Cf. Broadhead, ad loc.

page 4 note 4 Editors generally print στεν⋯ζω, though Μ gives στεν⋯ξω at 788 (but not at 818). It should be clear that στεν⋯ξω, which gives a closer rhyme with ῥ⋯ξω, may well be right For similar variations in the manuscripts between -ζω and -ξω cf. Fraenkel on Ag. 785.

page 4 note 5 Fraenkel and Kranz give a few examples from Euripides. As Fraenkel notes (op. cit., p. 365 [ = p. 346] n. 2) the device is common in anapaests, the metre of Ag. 1541.

page 4 note 6 I accept Broadhead's κρηνα⋯ου γ⋯νους, but not his suggestion κ⋯πῳ for κενο⋯: ‘(distressed) by the exhaustion of breathlessness’ is scarcely a natural expression. The likelihood that a lacuna follows after 484 does not affect my conjecture.