No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

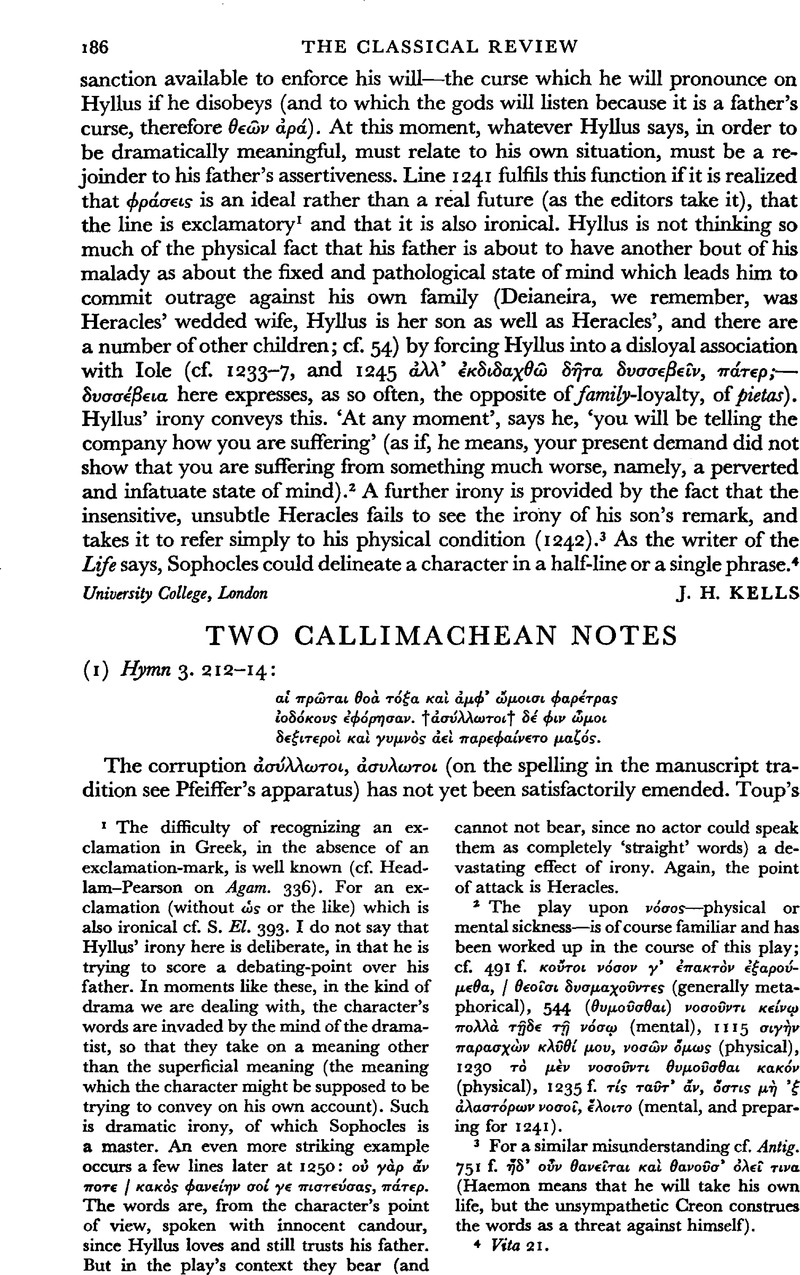

Two Callimachean Notes

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1962

References

page 186 note 1 The difficulty of recognizing an exclamation in Greek, in the absence of an exclamation-mark, is well known (cf. Headlam–Pearson on Agam. 336). For an exclamation (without ὡς or the like) which is also ironical cf. S. El. 393. I do not say that Hyllus' irony here is deliberate, in that he is trying to score a debating-point over his father. In moments like these, in the kind of drama we are dealing with, the character's words are invaded by the mind of the dramatist, so that they take on a meaning other than the superficial meaning (the meaning which the character might be supposed to be trying to convey on his own account). Such is dramatic irony, of which Sophocles is a master. An even more striking example occurs a few lines later at 1250: οὐ γ⋯ρ ἄν ποτε / κακ⋯ς φανε⋯ην σο⋯ γε πιστε⋯σας, π⋯τερ. The words are, from the character's point of view, spoken with innocent candour, since Hyllus loves and still trusts his father. But in the play's context they bear (and cannot not bear, since no actor could speak them as completely ‘straight’ words) a devastating effect of irony. Again, the point of attack is Heracles.

page 186 note 2 The play upon ν⋯σος—physical or mental sickness—is of course familiar and has been worked up in the course of this play; cf. 491 f. κοὔτοι ν⋯σον γ' ⋯πακτ⋯ν ⋯ξαρο⋯μεθα, / θεοῖσι δυσμαχο⋯ντμαχο⋯ντες(generally metaphorical), 544 (θυμο⋯σθαι) νοσο⋯ντι κε⋯νῳ πολλ⋯ τῇδε τῇ ν⋯σῳ (mental), 1115 σιγ⋯ν παρασχὼν κλῖθ⋯ μου, νοσ⋯ν ⋯μως (physical), 1230 τ⋯ μ⋯ν νοσο⋯ντι θυμο⋯σθαι κακ⋯ν (physical), 1235 f. τ⋯ς ταῖτ' ἄν, ⋯στις μ⋯ ᾽ξ ⋯λαστ⋯ρων νοσοῖ, ἕλοιτο (mental, and preparing for 1241).

page 186 note 3 For a similar misunderstanding cf. Antig. 751 f. ἥδ' οὖν θανεῖται κα⋯ θανο⋯σ' ⋯λεῖ τινα (Haemon means that he will take his own life, but the unsympathetic Creon construes the words as a threat against himself).

page 186 note 4 Vita 21.

page 187 note 1 Mair, whose Sprachgefühl was very subtle, subtle, prudently writes in a note ad loc. (p. 78 of his edition, in die Loeb series): ‘the MS. ⋯σ⋯λ(λ) is quite unknown. The translation assumes a connexion with ἄσιλλα': he significantly left the connexion unspecified, from the morphological point of view.

page 187 note 2 On ‘Artemis amazonenhaft’ cf. Roscher, s.v. Artemis, col. 602 ff.; cf. col. 603, on the type with ‘Entblößung der einen Brust’. The Amazons had, as a rule, ‘die rechte Brust entblößt’; cf. Roscher, s.v. Amazonen, col. 276.

page 187 note 3 Cahen, who leaves ⋯σ⋯λλωτοι between obeli, translates ‘du côté droit l'épaule était sans agrafe’ (italics mine) ‘et le sein se voyait nu’; in Passow5 ⋯σ⋯λωτος is, though dubiously, entered as meaning ‘entblößt’, and the same sense is accepted by Bailly (‘οù il n'y a rien à dépouiller, nu’): but, apart from the fact that συλ⋯ω does not exist, ⋯σ⋯λωτος as a synonym of ἄσυλος ‘inviolate’, ‘unplundered’, could hardly suggest the idea of being naked.

page 187 note 4 Grammatical theorizing by implication played a very important role in Alexandrian Buchpoesie: cf. e.g. Gillies on Apoll. iii. 184 (⋯εργομ⋯νοισιν), or on Apoll. iii. 245 (Apollonius' spelling of the name Ἀχ⋯λλης); see also Gillies, Introd., p. xxvii (‘reproduction of undecided alternatives’). The practice was extensively followed by Nonnus, the last of the Greek grammarian-poets. The alternation ⋯φᾱ́ρωτος ∼ ⋯φᾱ́ρωτος, with the semantic difference between the two adjectives, has a clear sous-entendu: Callimachus wants us to know that φ⋯ρος, cloak, in his opinion must only have a long a; he is, of course, polemizing with his rival Apollonius, who wrote (iii. 863) φᾰρ⋯εσσιν.

page 187 note 5 The ‘equation’ ἄφᾸρος: ἄφ⋯ρος= ⋯φᾱ́ρωτος: ⋯φᾱ́ρωτος is now complete. Nonnus was a past-master at such games.

page 188 note 1 As a cloak without sleeves, the φ⋯ρος was of course ideal for Artemis and her companions, who were hunting with bows and arrows.

page 188 note 2 On the ‘Ptolemäisch-römische Majuskelkursive’ in papyri see Gardthausen, , Griech. Pal. ii2. 173 ff.Google Scholar

page 188 note 3 Cf. Gardthausen, op. cit., p. 182, and Thompson, , Introd. to Gr. and Lat. Pal., p. 190 (an example of CI = φ from the third century B.C. is given on p. 191).Google Scholar

page 188 note 4 The locution οὐ ν⋯μεσις, both in the epigram and in the hymn, means ‘not unnaturally’ (‘il ne faut pas s'étonner si …’, Bailly). In the epigram it is, however, felicitously used with reference to the βασκαν⋯η. Cf. Thes., s.v. ν⋯μεοις, col. 1419 a and c, on the semantic association between ν⋯μεσις and invidia. The best rendering might be ‘there should be no envious astonishment (for my success)’. The association did not escape Herter, whose interpretation of οὐ ν⋯μεσις (Burs. Jahresber. cclv [1937], 187) only slightly differs from mine.

page 188 note 5 The papyrus of the Aitia is mutilated in the portion which should have contained the words μ⋯ λοξῷ; the expression ⋯μματι μ⋯λοξῷ in the text quoted by the scholiast on Hesiod may have been a Verschlimmbesserung by a scribe, who could make no sense of ἄχρι β⋯ου (on the current ⋯μματι λοξῷ et sim. cf. the material collected by Pfeiffer on. Aet. i. 1. 37 f.).