No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

The purpose of this note is to defend the following reading, offered by a minority of manuscripts, at Sat. 6.6.

Even if the evidence of the manuscripts showed merely that egregius… senes was an eleventh-century conjecture which gained a very moderate degree of acceptance, the reading would still have much to commend it.

page 145 note 1  Paris Lat. 9345 are corrections, contemporary or near-contemporary, of an original egregios (… senes). They were made (surely?) on other manuscript authority, or at least as independent conjectures, and are unlikely either to have been casually made in view of the increased difficulty they produce or (for the same reason) to be halfcompleted changes to the easy and obvious

Paris Lat. 9345 are corrections, contemporary or near-contemporary, of an original egregios (… senes). They were made (surely?) on other manuscript authority, or at least as independent conjectures, and are unlikely either to have been casually made in view of the increased difficulty they produce or (for the same reason) to be halfcompleted changes to the easy and obvious ![]()

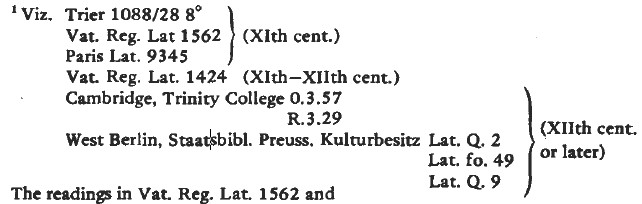

For the dates of these manuscripts and correctors see (in the order of the list given above) Kentenich, G., Beschr. Verzeicbnis derHschrr. der Stadtbibl. zu Trier (1931), vol. 10, pp.15–16;Google ScholarRobathan, D. M., CP 26 (1931), 289,Google Scholar cf. 299; information supplied to me by the Cab. des manuscrits, Bibliothèque Nation ale; Clausen, W. (Oxford, 1956), p.41;Google ScholarJames, M. R., The Western Manuscripts in the Library of Trin. Coll. Cambridge (1900–1902), nos. 1229, 609;Google ScholarRose, V.Die Hschr.-Verzeicbnisse der Königl. Bibl. zu Berlin, 2 Bd. 3 Abt. (1905), nos. 916,991, 1009.Google Scholar

Trier 1088/28 8°/° is perhaps Jahn's manuscript Tr (Prolegg., 1843, p.CCIX). It has, and the other Trier MS., 1089/26 8°, has not, the required reading at Pers. 6.6 (cf. Jahn, , 1843 edn., p.61).Google Scholar too, is more nearly ‘forma quadrata’’ (Jahn) than the other manuscript, to judge from the copies of single pages of each kindly sent to me; and its overall dimensions (14 X 19 cm) fit that description better than those of 1089/26 8°, which are 14 X 21 cm.

See Clausen, W. (Oxford, 1956), pp.xviii–xxi on the respect occasionally due to secondary manuscripts of Persius. All symbols used for manuscripts in the textual apparatus above are the ones used in this edition.Google Scholar

page 145 note 2 ![]() is the reading of the five manuscripts in the textual apparatus above; of a large majority (apparently) of Jahn's manuscripts (1843 edn.) although (Clausen, , op. cit., p.xvi)Google Scholar his information was not always accurate; and of a majority of other manuscripts so far as my inquiries have gone: all eighteen manuscripts in the Bodleian Library, Oxford (one Xth cent., one Xlth, remainder XVth); the four Hamilton manuscripts in the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek, Berlin (XlVth cent, or later); Codd. Norimbergensis, Ottoburanus, Trevirensis 1089, Turnacensis, Valentian– ensis 410 (Clausen, , op. cit., pp. xiii, 40);Google Scholar nine manuscripts in the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris (one Xlth cent, two XHth, remainder later). On Vat. Reg. Lat. 1562, Paris. Lat. 9345 see n.l above. I have not so far discovered an example of the reading

is the reading of the five manuscripts in the textual apparatus above; of a large majority (apparently) of Jahn's manuscripts (1843 edn.) although (Clausen, , op. cit., p.xvi)Google Scholar his information was not always accurate; and of a majority of other manuscripts so far as my inquiries have gone: all eighteen manuscripts in the Bodleian Library, Oxford (one Xth cent., one Xlth, remainder XVth); the four Hamilton manuscripts in the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek, Berlin (XlVth cent, or later); Codd. Norimbergensis, Ottoburanus, Trevirensis 1089, Turnacensis, Valentian– ensis 410 (Clausen, , op. cit., pp. xiii, 40);Google Scholar nine manuscripts in the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris (one Xlth cent, two XHth, remainder later). On Vat. Reg. Lat. 1562, Paris. Lat. 9345 see n.l above. I have not so far discovered an example of the reading ![]() to add to those (six altogether) in the textual apparatus above.

to add to those (six altogether) in the textual apparatus above.

One fifteenth-century manuscript, Paris Lat. 16696, before correction to -os… -es, had egregios … senex which is perhaps due to half-correction of one version in the light of the other. It might be urged that this pointed to a similar origin for the reading -us … -es which is here being defended. However, die Paris manuscript's reading is, so far as I know, unique and belongs to an age when correction, including halfcorrection, would be especially likely to occur. The -us … -es reading deserves more consideration because (see text) it explains how both alternative versions would first arise, and offers good sense; also because it is not unique and is older.

I sincerely thank Dr. Laufner, Librarians of the Vatican Library, Mme P. Bourgain, T. Kaye Esq., Dr. G. Achten, Dr. B. Barker-Benfield, and Dr. H.-E. Teitge for their correspondence, generously and indispens– ably informative, concerning both dates and readings of manuscripts mentioned here and in n.l.

page 146 note 1 I have wondered if the style of lines 2–6 of this poem, on the poetry of Caesius Bassus, is not purposely modelled to suggest the style of lyric, although the various types of expression it contains in combination are often used separately by Persius in this poem and elsewhere (e.g. 5.15–16, 6.23–4; 3.16–17, 22; 5.20; 5.3–4). The lengthy extension of a sentence (lines 3–6) by parallel expressions consisting of a predicative adjective followed by an explanatory infinitive is reasonably common in Horace's Odes (e.g. 1.35.2–4, 3.12.10–12, 4.12.19– 20); so is the use of words ![]() (vivunt (2), intendisse (4), egregius (6), and perhaps also pollice honesto (5), cf. Odes passim, e.g. 4.9.47–9, 3.24.25–6, 3.11.5–6). Probably the best sense for line 3 is to be obtained by ignoring the more obvious connection of veterum with vocum (and taking numeris veterum and primordia vocum as separate pairs, Beikircher, H., (1969), pp.21–2),Google Scholar cf. Odes 1.1.6 dominos, 1.35.6 ruris (Nisbet–Hubbard ad locc), and there is ‘syllepsis’’ in the use of intendisse with both primordia vocum and marem strepitum (Horatian examples of zeugma and syllepsis, Kiessling–Heinze, Odes 1.9.20). If this idea is justified, the shape of phrase produced by reading senes would contribute to the imitation too, cf. Odes 1.11.4 plures hiemes … ultimam, 2.3.1–3 aequam … rebus in arduis … mentem … in bonis … temperatam …, 2.9.10–12 Vespero surgente … fugiente …. The variation of style for purposes including that of literary pastiche would not be strange in Persius: in addition to Sat. 1, cf. 5.1–9, 161–6, 6.62.

(vivunt (2), intendisse (4), egregius (6), and perhaps also pollice honesto (5), cf. Odes passim, e.g. 4.9.47–9, 3.24.25–6, 3.11.5–6). Probably the best sense for line 3 is to be obtained by ignoring the more obvious connection of veterum with vocum (and taking numeris veterum and primordia vocum as separate pairs, Beikircher, H., (1969), pp.21–2),Google Scholar cf. Odes 1.1.6 dominos, 1.35.6 ruris (Nisbet–Hubbard ad locc), and there is ‘syllepsis’’ in the use of intendisse with both primordia vocum and marem strepitum (Horatian examples of zeugma and syllepsis, Kiessling–Heinze, Odes 1.9.20). If this idea is justified, the shape of phrase produced by reading senes would contribute to the imitation too, cf. Odes 1.11.4 plures hiemes … ultimam, 2.3.1–3 aequam … rebus in arduis … mentem … in bonis … temperatam …, 2.9.10–12 Vespero surgente … fugiente …. The variation of style for purposes including that of literary pastiche would not be strange in Persius: in addition to Sat. 1, cf. 5.1–9, 161–6, 6.62.

page 147 note 1 Schanz–Hosius ii. 484.

page 147 note 2 The Life does not, it is true, mention Lucan, who was Persius' near-contemporary, until the next sentence; but this is because he is mentioned as one of a group of friends made somewhat later in Persius' career, especially through his attendance upon Cornutus.

It is possible to read senex while maintaining that Bassus was a young man if we say that the word does not refer literally to Bassus' age but to a pose of advancing years adopted by Bassus in the poems Persius is discussing. Yet this is less than satisfactory, because senex is fairly clearly related by function to opifex (line 3). As that does not refer to a poetic pose, it is not natural to assume that senex does so.