No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

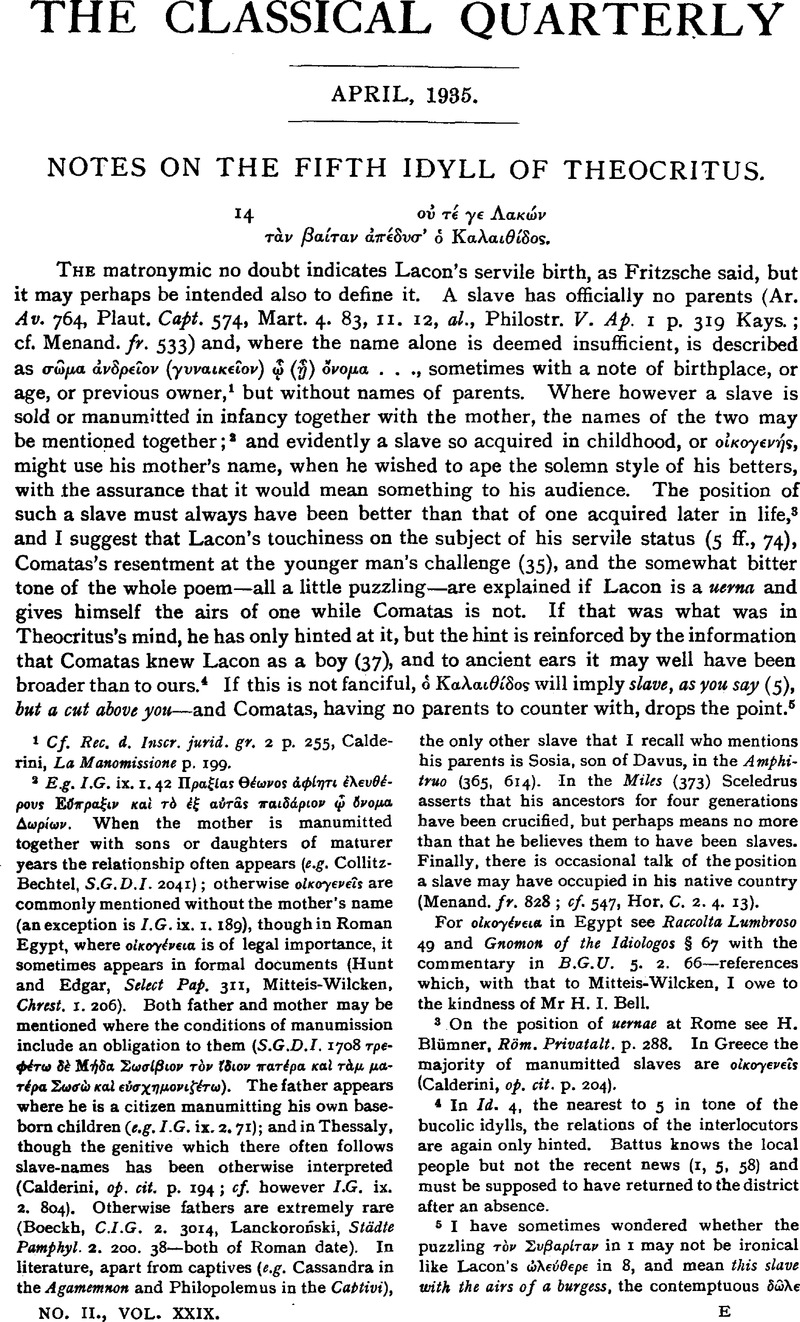

Notes on the Fifth Idyll of Theocritus

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Other

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1935

References

page 65 note 1 Cf. Rec. d. Inscr. jurid. gr. 2 p. 255, Calderini, , La Manomissione p. 199Google Scholar.

page 65 note 2 Eg. I.G. ix. 1.42 Πραξ⋯ασ θ⋯ωνοσ ⋯φ⋯ητι ⋯λενθ⋯ρονσ E⋯πραξιν κα⋯ τ⋯ ⋯ξ αὐτ⋯σ παιδ⋯ριον ᾧ ⋯νομα Δωρ⋯ων. When the mother is manumitted together with sons or daughters of maturer years the relationship often appears (e.g. Collitz-Bechtel, S.G.D.I. 2041); otherwise οἰκογɛνεῖς are commonly mentioned without the mother's name (anexception is I.G. ix. 1. 189), thongh in Roman Egypt, where οἰκογ⋯νεια is of legal importance, it sometimes appears in formal documents (Hunt, and Edgar, , Select Pap. 311Google Scholar, Mitteis-Wilcken, , Chrest. 1. 206)Google Scholar. Both father and mother may be mentioned where the conditions of manumission include an obligation to them (S.G.D.I. 1708 τρεφ⋯τω δ⋯ M⋯δα Σωσ⋯βιον τ⋯ν ἴδιον πατ⋯ρα κα⋯ τ⋯μ ματ⋯ρα Σωσώ κα⋯ εὐαχημονιζ⋯τω). The father appears where he is a citizen manumitting his own baseborn children (e.g. I.G. ix. 2. 71); and in Thessaly, though the genitive which there often follows slave-names has been otherwise interpreted (Calderini, , op. cit. p. 194Google Scholar; cf. however I.G. ix. 2. 804). Otherwise fathers are extremely rare (Boeckh, C.I.G. 2. 3014, Lanckoronski, Städte Pamphyl. 2. 200. 38—both of Roman date). In literature, apart from captives (e.g. Cassandra in the Agamemnon and Philopolemus in the Cattivi), the only other slave that I recall who mentions his parents is Sosia, son of Davus, in the Amphitruo (365, 614). In the Mills (373) Sceledrus asserts that his ancestors for four generations have been crucified, but perhaps means no more than that he believes them to have been slaves. Finally, there is occasional talk of the position a slave may have occupied in his native country (Menand. fr. 828; cf. 547, Hor. C. 2. 4. 13).

For οἰκογ⋯νεια in Egypt see Raccolta Lumbroso 49 and Gnomon of the Idiologos § 67 with the commentary in B.G.U. 5. 2. 66—references which, with that to Mitteis-Wilcken, I owe to the kindness of Mr H. I. Bell.

page 65 note 3 On the position of uernae at Rome see Blümner, H., Röm. Privatalt. p. 288Google Scholar. In Greece the majority of manumitted slaves are οἰκογενενεῖς (Calderini, , op. cit. p. 204)Google Scholar.

page 65 note 4 In Id. 4, the nearest to 5 in tone of the bucolic idylls, the relations of the interlocutors are again only hinted. Battus knows the local people but not the recent news (I, 5, 58) and must be supposed to have returned to the district after an absence.

page 65 note 5 I have sometimes wondered whether the puzzling τ⋯ν Συβαρ⋯ταν in I may not be ironical like Lacon's wheidepe in 8, and mean this slave with the airs of a burgess, the contemptuous δ⋯λε Σιβὺρτα of Comatas's next speech showing what was intended. Wilamowitz's excision of 73 removes some of the Lacon, a slave, could be called ⋯ Συβαρ⋯της, and, for other reasons, it seems to me improbable. The problem is however complicated by our ignorance of the meaning of Συβαρ⋯της (as compared with θο⋯ριος) in the 3rd cent. B.C., or (as perhaps one should rather say) in the mind of Theocritus.

page 66 note 1 Cf. Wilamowitz, , Textgeschichte p. 134Google Scholar.

page 66 note 2 And was possibly so understood by Rufinus, , since A.P. 5. 28 is reminiscent of this context: cf. Hermes 15. 456Google Scholar.

page 67 note 1 For the damage done by locusts to vines see AT. AV. 588. Two vases depict them in the act: Pfuhl, , Mai. u. Zeichn. fig. 212Google Scholar, C.V. Oxford 2, II D X. Plagues of grasshoppers however occur (Uvarov, B. P., Locusts and Grasshoppers p. 167Google Scholar. Times Nov. 3, 1934, p. 12, Nov. 6, p. 14).

page 67 note 2 Migne, , P.L. 25. 1325, 1330Google Scholar.

page 67 note 3 Theophrastus distinguishes ⋯κρ⋯ς the fullgrown locust, from ⋯ττ⋯λεβοσ but regards βρο⋯χοι as a species of the latter. See also Hes. and Phot. s.v. ⋯κορνο⋯σ.

page 67 note 4 On these insects generally see Keller, Ant. Tierwelt, 2Google Scholar. 455, Pauly-Wissowa 8. 1381.

page 67 note 5 I will not argue that the season is autumn (83) and that the vines therefore are not pubesantes, for I very much doubt whether the rules of the game these two are playing require their couplets to be either true or consistent.

page 68 note 1 Ztschrft f. d. Alterthumswiss. 1837, p. 228. This paper is not reprinted in Hermann's Opuscula.

page 68 note 2 E.g. Theophr, . H. P. 4Google Scholar. 12. 3 αὕτη δ⋯ [⋯ῥ⋯ζα] αὐα⋯νεται καθ' ἕκαστον ⋯νιαυτ⋯ν, εἶθ' ⋯τ⋯ρα π⋯λιν ⋯π⋯ τ⋯ς κεφαλ⋯ς το⋯ σχο⋯εται, το⋯το δ⋯ κα⋯ ⋯ν τῇ ⋯ψει φανερ⋯ν ἰδεῖν τ⋯σ μ⋯ν αὔας τ⋯ς δ⋯ χλωρ⋯ς καθιεμ⋯νας.

page 68 note 3 Uvarov, , op. cit. p. 73Google Scholar.

page 68 note 4 Ib. p. 74. To illustrate the importance of moisture to these insects, the author cites the case of a swarm devouring the damp washing from a clothes-line but sparing the garments already dry.

page 68 note 5 “Aμπελος among the glosses to ἤβη in Hesychius presumably indicates that it was known to him.

page 69 note 1 Hermann, (Opusc. 8. 333)Google Scholar, followed by Meineke, supposed that six lines of Daphnis's song have fallen out after 16; but the simile in 15 f., though only lightly attached to what follows, is proquite intelligible and does not afford real ground for suspicion. Haupt's, opinion (Opusc. 1. 177)Google Scholar that 41 has replaced a genuine verse, and that the songs are multiples of seven, also seems improbable.

page 69 note 2 For the present purpose the exact number of quatrains is immaterial, but I assume that Hermann was wrong in excising 57–60 and Wuestemann right in supposing that one of Daphnis's quatrains is missing after 52. I do not think it has been pointed out that the elaborate balance of 33–48 is continued in 53–60 where Menalcas sings of the pleasures of love as compared with other pleasures, Daphnis of Ratzethe pains of love compared with other pains, Menalcas's quatrain 49–52 thus lacks a pair.

page 69 note 3 Since this paper was written A. von Blumenthal has advanced, in Pauly-Wissowa (5 A 2011), the surprising opinion that Id. 5 contains, not a singing-competition, but the parody of an agon such as is found in Aristophanes and in the Certamen Hesiodi it Hotneri. A singing-competition must needs be an agon, and there is inevit. ably some general resemblance between this and those; there is, however, a much closer resemblance to the singing-competition in 8, the proceedings, like the songs in 7, are described as βουκολιασμ⋯ς (5. 44, 68; 7. 36), and if analogies are to be looked for outside Bucolic, sholia, Theogn. 1039 ff., and the aulodiat in p. Ox. 1795 (Collect. Alex. p. 199) seem to offer a more promising field, though the scope of improvisation in sholia is obscure. Neither in 5 nor in 4. 32 ff., where von Blumenthal also detects it, can I see any sign of parody.

page 69 note 4 One is that of Wernsdorf (cited by Kiessling p. 78) that Lacon is jactantiori stultior animique impotentior, but this, even if true, is no ground for deciding a musical competition. The second is that of Deicke, L. (Jahresb. d. Gymn. xu Ratzethe burg 1912)Google Scholar, who holds that Lacon loses because he counters Comatas's negative in 132 with a positive. It is true that this does not happen else where, but if it were against the rules (and there is no apparent reason why it should be) it is mere stupidity of Lacon to infringe them.

page 69 note 5 Textgeschichte p. 123: see p. 70 n. 4.

page 70 note 1 These points are noted by Legrand, , Etude p. 163Google Scholar.

page 70 note 2 Legrand's explanation (on 6. 5) is not very satisfactory in itself and does not take account of all the facts. In Virgil Ecl. 3 the challenger begins: in 7 and 9 the preliminaries of the contest are not disclosed: in 5 the songs are hardly in competition. In Calpurnius Ecl. 2 the point is decided by a preliminary game of morra. On the grounds of decision in V. Ecl. 3 see C.R. 47. 216.

page 70 note 3 At 139 Morson seems to have forgotten them, for the lamb which Comatas receives is not a prize offered by Morson but Lacon's stake, and προσκρ⋯νει rather than δωρεῖται is the appropriate verb. I have dealt with some passages which provoke similar doubts in C.Q. 24. 146.

page 70 note 4 In 5 Wilamowitz says der Unterschied liegt tiefer als in der mangelnden Erfindsamkeit. Lakon bringt allerdings nichts als Parallelen zu den unerschöpflichen Einfällen des Komatas, and' certainly the reader becomes a little bored with Lacon. But, given the follow-your-leader convention, it could hardly be otherwise when Coraatas always has the initiative and the contest extends to fourteen exchanges, though Lacon is never so close to Comatas as Daphnis, the ultimate victor, to Menalcas in 8. 33–48. As I have said (above p. 68), Lacon claims, and Comatas admits, that the fight has been hard, and if Morson had been of Wilamowitz's opinion he ought to have intervened much earlier.

page 72 note 1 The two explanations of the decision known to me disregard this line. Wernsdorf again detects a superiority of morals in the victor; Wilamowitz's opinion (Textgeschichte p. 123) is based on an analysis which seems to me fanciful.