No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

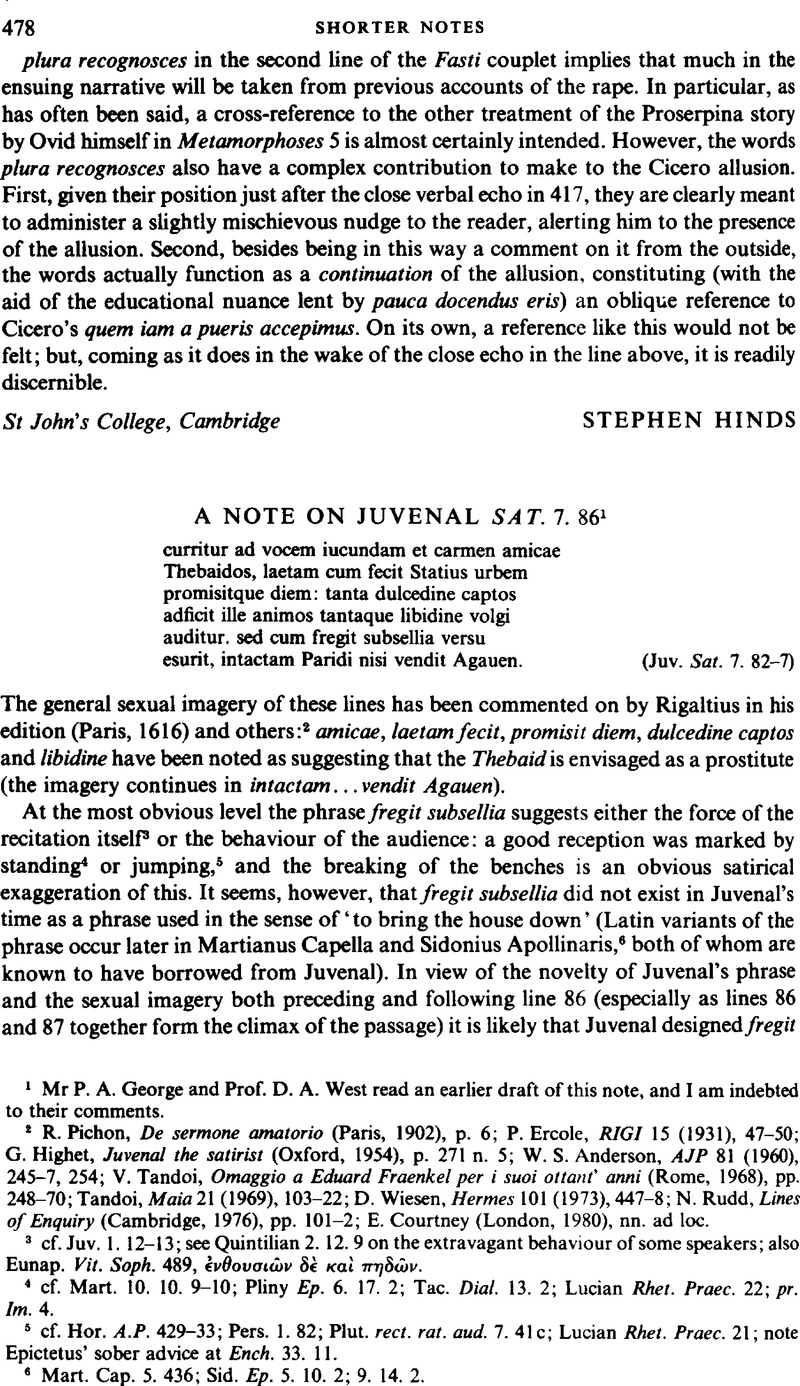

A Note On Juvenal Sat. 7. 861

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Shorter Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1982

References

2 Pichon, R., De sermone amatorio (Paris, 1902), p. 6Google Scholar; Ercole, P., RIGI 15 (1931), 47–50Google Scholar; Highet, G., Juvenal the satirist (Oxford, 1954), p. 271 n. 5Google Scholar; Anderson, W. S., AJP 81 (1960), 245–7, 254Google Scholar; Tandoi, V., Omaggio a Eduard Fraenkel per i suoi ottant' anni (Rome, 1968), pp. 248–70Google Scholar; Tandoi, , Maia 21 (1969), 103–22Google Scholar; Wiesen, D., Hermes 101 (1973), 447–8Google Scholar; Rudd, N., Lines of Enquiry (Cambridge, 1976), pp. 101–2CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Courtney, E. (London, 1980), nn. ad loc.Google Scholar

3 cf. Juv. 1. 12–13; see Quintilian 2. 12. 9 on the extravagant behaviour of some speakers; also Eunap. Vit. Soph. 489, ![]()

4 cf. Mart. 10. 10. 9–10; Pliny Ep. 6. 17. 2; Tac. Dial. 13. 2; Lucian Rhet. Praec. 22; pr. Im.4.

5 cf. Hor. A.P. 429–33; Pers. 1. 82; Plut. rect. rat. Aud. 7. 41c; Lucian Rhet. Praec. 21; note Epictetus' sober advice at Ench. 33. 11.

6 Mart. Cap. 5. 436; Sid. Ep. 5. 10. 2; 9. 14. 2.

7 Wiesen, op. cit., p. 477, writes that Juv. 7. 86 is ‘wittily ambiguous’, but his note (p. 478 n. 1) indicates that the ambiguity he referes to is that between the effects of the speaker and of the audience.

8 cf. Catull. 6. 10–11; Juv. 9. 77–8, where see Courtney's parallels and add Ov. Am. 3. 14. 26 and probably Argentarius A.P. 5. 127. 5 (see Gow-Page, GP (Cambridge, 1968) at 1359)Google Scholar.

9 For a male audience and female poem compare the rather different metaphoric scene in Pers. 1. 17 ff. (cf. Ar. Thesm. 130–3, and for Persius see Gratwick, A. S., CQ n.s. 23 (1973), 81–2CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and Bramble, J., Persius and the programmatic satire (Cambridge, 1974), pp. 73–95). It should be noted that this group scene contrasts with the individual service given to Paris (perhaps recalling the gift of Helen).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

10 At Juv. 3. 136 alta sella (cf. Pers. 1. 17, sede celsa) appears to connote display of goods: cf. Ruperti ad loc. and Fest. Paul. 226M on prosedae; sella at Plaut. Poen. 228; ![]() Aeschines 1. 74 (see Dover, K. J., Greek Homosexuality (London, 1979), p. 108)Google Scholar; for sedere see Herescu, , Glotta 38 (1960), 125–34Google Scholar. The display use does not preclude a professional function: Oswald, , Index of figure types on terra sigillata part IV (Liverpool, 1937)Google Scholar, pl. 90 figs. F, G, H, I show a tall pillar-like seat (alta sella?) supporting the woman during intercourse.

Aeschines 1. 74 (see Dover, K. J., Greek Homosexuality (London, 1979), p. 108)Google Scholar; for sedere see Herescu, , Glotta 38 (1960), 125–34Google Scholar. The display use does not preclude a professional function: Oswald, , Index of figure types on terra sigillata part IV (Liverpool, 1937)Google Scholar, pl. 90 figs. F, G, H, I show a tall pillar-like seat (alta sella?) supporting the woman during intercourse.

11 Tac. Ann. 6. 1: since they were named after the room sellae seem to have been required for the practice.

12 Suet. Tib. 43: the room in which the sellarii gathered (not sellaria, as LS).

13 The schol. at Juv. 3. 136 (alta sella) writes inde sellariae dicuntur (but Tacitus states that sellarius was a coinage of Tiberius' time: it may seem unlikely that in the interim it lost its original connection).

14 Trossulus exultat tibi per subsellia levis: for the connotations of the words other than subsellia see Bramble op. cit. (n. 9), pp. 122–6.

15 See Oswald cited n. 10 above, adding pi. 91 figs. EE, GG; Dover, op cit., pi. R790 and p. 87 n. 49, p. 101 on B694; G. Vorberg, Glossarium eroticum (1965), p. 640.

16 cf. Juv. 6. 63 ff.

17 On the literary level intactam may suggest a poem which Statius is forced to sell to Paris to be recast into a pantomime. Cf. Suet. Nero 4 for Nero's proposal to dance Vergili Turnum (cf. Ferguson ad loc.).

18 In other passages where literary prostitution or pandering is at point the emphasis is on the enticing or the effeminate aspects and not the financial. See Ar. Batr. 1301; Thesm. 130–3; Plato Lg. 659c; Dion. Hal. Oral. Vett. 1; Plut. rect. rat. Aud. 46a ![]() ; Pers. 1. 134 (Callirhoe is a suitably named prostitute as well as a poem: see index to CIL 6 for some freedwomen of the name); Sen. Ep. 114. 15 (blanditur); Quint. 5. 2. 17; 9. 4. 28; Pliny, Ep. 2. 19. 7; Tac. Dial. 26. 1; Lucian, Rhet. Praec. 23; Donatus Vit. Verg. 29 (lenociniis); the lemmatist at A.P. 5. 55; Athen. 13. 567b. The financial aspect is hinted at in Hor. Epp. 1. 20, but otherwise only Juvenal gives a clear indication of the financial complexity of the moral environment.

; Pers. 1. 134 (Callirhoe is a suitably named prostitute as well as a poem: see index to CIL 6 for some freedwomen of the name); Sen. Ep. 114. 15 (blanditur); Quint. 5. 2. 17; 9. 4. 28; Pliny, Ep. 2. 19. 7; Tac. Dial. 26. 1; Lucian, Rhet. Praec. 23; Donatus Vit. Verg. 29 (lenociniis); the lemmatist at A.P. 5. 55; Athen. 13. 567b. The financial aspect is hinted at in Hor. Epp. 1. 20, but otherwise only Juvenal gives a clear indication of the financial complexity of the moral environment.