Article contents

The Methone Decrees1

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

The series of decrees concerning Methone throws welcome light on Athenian foreign policy and the imperialism of Pericles' successors. Here is historical evidence of the highest quality. Are we using it as fully and accurately as we should? This paper is written in the belief that we are being hampered by unsound presuppositions. Chronologically the second decree is our main fixed point. It was passed in the first prytany of 426/5 B.C. The third and fourth decrees followed in the next two archon-years. They can be ignored in this discussion, since one is hopelessly mutilated and the other is missing from the stone as it stands now. The real problem rises over the first decree. What is its date? It used commonly to be put in 428/7 B.C. until West argued powerfully for January/February 429/8 B.C. His view won considerable support, but the editors of The Athenian Tribute Lists have since succeeded in establishing the summer of 430 B.C. as the orthodox dating. Now those who accept this should recognize that it creates an awkwardly long gap between the first and second decrees. By the first decree Methone was permitted to pay the quota alone, instead of its full tribute, and was promised separate, favourable treatment of its arrears in return for continued loyalty.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1961

References

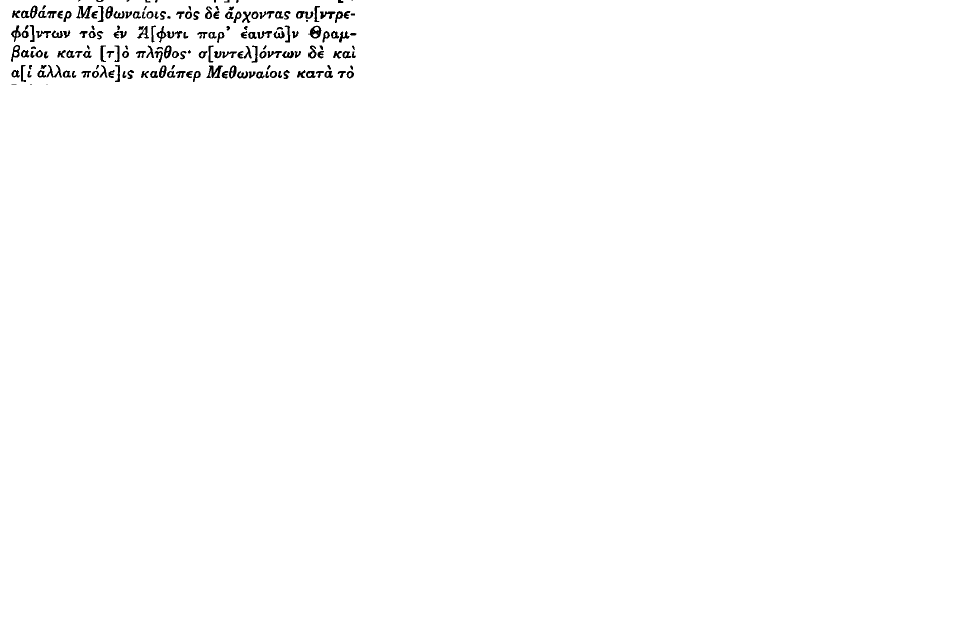

page 154 note 2 For the text of the decrees see Tod, , GHI i, no. 61Google Scholar (IG i2. 57 +) and ATL ii, D3–6.Google Scholar The dates of D4–6 are convincingly demonstrated in ATL iii. 133 f. The missing D6 must be presumed from the fact that die whole dossier was inscribed by Phainippos, secretary for die eighth prytany in 424/3 B.C.Google Scholar

page 154 note 3 See Kirchhoff, A., Abh. Berl. Akad. 1861, pp. 555–606:Google Scholar U. Köhler, ibid, 1869, ii, p. 138: Hicks, and Hill, , GHI 2 no. 60, p. 103:Google ScholarWest, A. B., AJA xxix (1925), 440 ff.:CrossRefGoogle ScholarTod, , GHI i. 131:Google ScholarATL iii. 134:Google ScholarGomme, A. W., Commentary on Thucydides i. 214.Google Scholar As late as the 1930's some scholars still clung to 428/7 B.C.; see Lenk, in P.-W. xv. 1386Google Scholar and Geyer, in P.-W. xix 597 f.Google Scholar

page 154 note 4 For Perdikkas' intentions see Geyer, , loc. cit.Google Scholar and ATL iii. 136.Google Scholar For the Macedonian claim on Methone, Pydna, and Therme see Kahrstedt, U., Hermes lxxxi (1953), 85–92 and 96 ff.Google Scholar Despite P. A. Brunt's challenging paper (AJP lxxii [1951], 269–82Google Scholar) the traditional dating and interpretation of die Megarian Decrees still seems valid to me. Pericles intended to coerce Megara into seceding from die Peloponnesian League once again. Tod gives an excellent fuller summary of die contents of D3 and 4.

page 155 note 1 Athens must promptly defend loyal friends in the Thraceward region. The ATL editors rather evade the issue in writing (n. 6 on p. 135) ‘The question in fact dragged several years' and on p. 136 ‘The two decrees of which we have substantial remains, D3 and 4, belong to this period; the covert hostility of Perdikkas is evident, and causes constant trouble to Methone. The envoys sent to compose the trouble in 430 (D3) evidently achieved little and there are two more embassies to Makedonia in 426 (D4). …’

page 155 note 2 See West, , AJA xxix (1925), 443Google Scholar and ibid. 434 ff. (with Meritt): SEG v. 25 and 28Google Scholar (new texts of IG i2. 216 ( + 217 and 231) and 218): Meritt, , Ath. Fin. Doc. (1932), pp. 3–25Google Scholar (his new view after the shifts recorded on pp. 6 f.): Doc. Ath. Trib. (1937), pp. 98–100 (the clinching arguments).Google Scholar

page 155 note 3 Meritt conclusively demonstrated the close links between the lists (Ath. Fin. Doc., pp. 7 ff.),Google Scholar but Nesselhauf continued to claim that IG i2. 216 was the earlier (Klio, , Beiheft xxx [1933], 69 n. a and 140 f.).Google Scholar Meritt's reply (AJP lv [1934], 285 f.Google Scholar) depends for its validity on the lists being firmly anchored in the two years at issue. In the year of IG i2. 216Google Scholar (see ATL 26. iv. 44 f.Google Scholar) Hairaia paid tribute both for the current and the previous year; restoring in 218 Meritt deduced that Hairaia defaulted in 431, paid for diat year in 430 (no current payment can be restored before or after the entry), and brought the record up to date in 429/8 B.C. (see Doc. Ath. Trib., p. 100Google Scholar and ATL i. 192Google Scholar). Restoring

in 218 Meritt deduced that Hairaia defaulted in 431, paid for diat year in 430 (no current payment can be restored before or after the entry), and brought the record up to date in 429/8 B.C. (see Doc. Ath. Trib., p. 100Google Scholar and ATL i. 192Google Scholar). Restoring , however, we can again put IG i2. 216 before 218;Google Scholar they do not appear in what little remains of the Ionic list in 216. Moreover, even if they did, the 218 payment might be of partial arrears.

, however, we can again put IG i2. 216 before 218;Google Scholar they do not appear in what little remains of the Ionic list in 216. Moreover, even if they did, the 218 payment might be of partial arrears.

page 155 note 4 See Ath. Fin. Doc., pp. 17–20Google Scholar and ATL i. 196 f.Google Scholar (date of IG i2. 214/15).Google Scholar Only the last two columns are preserved (Hellespont-Ionia). The Ionic-Carian names of IG i2. 222Google Scholar tell the same story; the stone evidendy has its right margin preserved (see ATL i. 99, 196 and 199: 427/6 or 426/5 B.C.?).Google Scholar

page 156 note 1 ATL i. 196.Google Scholar Compare p. 199 (of IG i2. 222).Google Scholar ‘The position of the Ionic panel associates the inscription with the period 428/7–426/5 B.C.’, and, for the general prin ciple, ATL iii. 68, where it is used to show that there were reassessments in 443/2 and 438/7 B.C.Google Scholar

page 156 note 2 See ATL ii. A9Google Scholar (IG i2. 63 + ), 4 ff.Google Scholar The order of the first two districts (both restored) cannot be reversed, with Ionia/Caria follow ing Thrace. See Meritt, , AJP lviii (1937). 153 f.Google Scholar for a vigorous defence of his spacing in the vital fifth line against Nesselhauf'i criticism (Gnomon xii [1936], 298).Google Scholar

page 156 note 3 For the problem raised by D7 (Kleinias' Decree), D14 (Coinage Decree), and Pericles' Congress Decree see Hist, x (1961), 158 ff.Google Scholar All are normally put in the early 440's, when the ATL editors discern behind the Quota Lists the basic order Ionia/Caria, Thrace, Hellespont, and Islands (iii. 30 ff.), which none of these decrees shows. On the ATL view the list of 430/29 B.C. displays an order unknown before and abandoned in 429/8 B.C.

page 156 note 4 In 420/5 B.C. the uniqueness of IG i2. 210Google Scholar is fully explained; the reassessment of 425 B.C. established the new order Islands-Ionia-Hellespont-Thrace, which seems to have been maintained henceforth. In Ath. Fin. Doc., p. 14,Google Scholar Meritt wrote: ‘The provision of the decree, therefore, for regular assessments at the time of the Greater Panathenaia is not only a safeguard for the future, but also a rebuke to the politicians of the previous year (426/5) for failing to carry out the reassessment at the proper time.’ But, as he had just remarked, ‘IG i2. 63Google Scholar itself represents an extraordinary assessment’. We might then fairly regard A9, 26–33 as a guarantee to the allies against any repetition of the irregularity, the more necessary if there had been a normal assessment only a year before. For 428/7 B.C. see Meritt, , op. cit., pp. 3–25,Google Scholar and Nesselhauf, , Klio, Beiheft xxx (1933), 70 ff. and 140.Google Scholar

page 156 note 5 Doc. Ath. Trib., pp. 98–100.Google Scholar

page 156 note 6 In IG i2, 218Google Scholar the rubrics run

(ATL 25. iii. 54 f.Google Scholar) and

(ATL 25. iii. 54 f.Google Scholar) and

(60 f.). The first can be restored in IG i2. 216Google Scholar (ATL 26. ii. 34 ff.Google Scholar), where only ot survives; but ON is clearly quite as likely a reading (see Atk. Fin. Doc., p. 10Google Scholar and ATL i. 96Google Scholar). The ATL restorations of the second rubric (26, ii. 43 f.)—

(60 f.). The first can be restored in IG i2. 216Google Scholar (ATL 26. ii. 34 ff.Google Scholar), where only ot survives; but ON is clearly quite as likely a reading (see Atk. Fin. Doc., p. 10Google Scholar and ATL i. 96Google Scholar). The ATL restorations of the second rubric (26, ii. 43 f.)—

— is still disturbingly unlike its counterpart, though preferable to earlier versions (see ATL i. 196Google Scholar and Ath. Fin. Doc., p. 11Google Scholar). For the correspondence between old and new rubrics see ATL iii. 80–88 (with a table on p. 88).Google Scholar For Nesselhauf's view see op. cit. pp. 71 and 141.Google Scholar West and Meritt themselves restored forms of the old rubrics in 1931 (SEC v, 25).Google Scholar With one alteration (middle for active; see Nesselhauf, p. 71) they remain plausible; epigraphically

— is still disturbingly unlike its counterpart, though preferable to earlier versions (see ATL i. 196Google Scholar and Ath. Fin. Doc., p. 11Google Scholar). For the correspondence between old and new rubrics see ATL iii. 80–88 (with a table on p. 88).Google Scholar For Nesselhauf's view see op. cit. pp. 71 and 141.Google Scholar West and Meritt themselves restored forms of the old rubrics in 1931 (SEC v, 25).Google Scholar With one alteration (middle for active; see Nesselhauf, p. 71) they remain plausible; epigraphically

appear sound. The double breach in the stoichedon order is permissible in a heading; see West, and Meritt, , AJA xxix (1925), 435 on

appear sound. The double breach in the stoichedon order is permissible in a heading; see West, and Meritt, , AJA xxix (1925), 435 on .Google Scholar

.Google Scholar

page 157 note 1 The ATL editors have convincingly defended (i. 205) their restoration

(‘last preceding’) against Nesselhauf (Gnomon xii [1936], 29)Google Scholar. For the ATL interpretation of

(‘last preceding’) against Nesselhauf (Gnomon xii [1936], 29)Google Scholar. For the ATL interpretation of see iii. 78 ff.; ‘archon-ship’ is the likeliest meaning in view of A9, 55f.

see iii. 78 ff.; ‘archon-ship’ is the likeliest meaning in view of A9, 55f.

page 157 note 2 For the status of these cities (privilege or imposition?) see the divergent views of Nesselhauf, (Klio, Beiheft xxx [1933], 59 ff. and 73Google Scholar) and ATL iii. 80–88Google Scholar (in contrast to ATL i. 456Google Scholar the group are now considered relatively favoured). I find it hard to accept the claim in ATL iii p. 83 f.Google Scholar that the

group are now considered relatively favoured). I find it hard to accept the claim in ATL iii p. 83 f.Google Scholar that the rubric means essentially the same as the

rubric means essentially the same as the rubric, replacing it in 430 B.C. The

rubric, replacing it in 430 B.C. The would be those of 434/3 B.C., whose assessment was simply taken over by their successors, since it carried a guaran tee. Gomme (CR liv [1940], 68 f.)Google Scholar followed Nesselhauf in insisting diat the

would be those of 434/3 B.C., whose assessment was simply taken over by their successors, since it carried a guaran tee. Gomme (CR liv [1940], 68 f.)Google Scholar followed Nesselhauf in insisting diat the were the board who ‘officially adopted the assessment originally proposed by the states themselves’. With ‘negotiated’ instead of ‘proposed’ (the point made in ATL iii. 85Google Scholar) this may well stand. After this action of the Assessors who were responsible for the list behind IG i2. 218Google Scholar (firmly tied down to the first year of a period; see Ath. Fin. Doc., pp. 6 and 9Google Scholar) these cities could henceforth be listed geographically as any others; hence IG i2. 216Google Scholar cannot follow 218. This is essen tially Nesselhauf's view, but he dates IG i2. 218 to 428/7 B.C. (an irregular assessment).Google Scholar

were the board who ‘officially adopted the assessment originally proposed by the states themselves’. With ‘negotiated’ instead of ‘proposed’ (the point made in ATL iii. 85Google Scholar) this may well stand. After this action of the Assessors who were responsible for the list behind IG i2. 218Google Scholar (firmly tied down to the first year of a period; see Ath. Fin. Doc., pp. 6 and 9Google Scholar) these cities could henceforth be listed geographically as any others; hence IG i2. 216Google Scholar cannot follow 218. This is essen tially Nesselhauf's view, but he dates IG i2. 218 to 428/7 B.C. (an irregular assessment).Google Scholar

page 157 note 3 See Meritt, , Atk. Fin. Doc., pp. 17–20,Google Scholar and ATL i. 196 ff.Google Scholar Notion was perhaps specially assessed by the people after its re covery and paid late for 428/7 B.C. (its normal tribute was 2000 D!).

page 158 note 1 See ATL i. 98 and 198.Google Scholar For Lesbos see Gomme, , Commentary on Thwydides, ii. 278 f.Google Scholar and the good comments in ATL i. 197.Google Scholar

page 158 note 2 Ath. Fin. Doc., pp. 17 f.Google Scholar

page 158 note 3 See Nesselhauf, , op. cit., p. 141,Google Scholar and rhuc. 3. 50. 3; 4. 52. 2–3 with 75. 1–2. For Rhoiteion see the acute argument in ATL iii. 88.Google Scholar Like Samos the rebel cities of Lesbos itself were never assessed tribute; see Thuc. 3. 50. 2.

page 158 note 4 For Besbikos see ATL iii. 81 f. n. 30Google Scholar and the table on p. 87. Its restoration in the rubric of IG i2. 218Google Scholar (ATL. 25. iii. 65) is most probable.Google Scholar

rubric of IG i2. 218Google Scholar (ATL. 25. iii. 65) is most probable.Google Scholar

page 158 note 5 So much can be deduced from the; pigraphical notes in ATL i. 96. The obverse face of List 26 is so weathered that no photo graph was published.Google Scholar

page 159 note 1 See the table in ATL iii. 87.Google Scholar

page 159 note 2 For Pleume, Aioleion, Chedrolos, and Miltoros see the table in ATL and Meritt, , Ath. Fin. Doc., pp. 23 f.Google Scholar (the first two). For their location see ATL i. 465, 520, 538 f., and 561.Google Scholar

page 159 note 3 On Nisyros see ATL i. 197 and 526.Google Scholar By curious oversight the editors declare (p. 197) ‘In 27, II, 30, as in all later occurrences, Nisyros is Ionic once more’ (my italics). But Nisyros does not appear again in the record after Lists 26 and 27; see ATL i 357 (Register).Google Scholar

page 159 note 4 See Kolbe, , Sitzb. Akad. Berlin 1930, p. 339:Google ScholarWest, and Meritt, , Athenian Assessment…, pp. 69f.:Google ScholarATL i. 228 f. (Register; (Kar.)).Google Scholar

(Kar.)).Google Scholar

page 159 note 5 For see ATL i. 240 and 472 f.Google Scholar For Astypalaia see ATL i. 241 (last certainly recorded in List 27).Google Scholar

see ATL i. 240 and 472 f.Google Scholar For Astypalaia see ATL i. 241 (last certainly recorded in List 27).Google Scholar

page 160 note 1 Thera was hostile in 431 B.C. (Thuc. 9. 4), but subject by 426 B.C. (IG i2. 65 = D8, 22 f.) and tributary to the tune of 3 talents (IG i2. 216 = ATL 26. iii. 23). For Lysikles see Thuc. 3. 19. 2; he may also have brought in Saros (first found in IG i2. 214/15 = ATL 27. iii. 21). My theory about the Island district can best be judged by reference to the loose map at the end of ATL i.

page 160 note 2 The Island panel is confined to col. ii. lines 7–28 in List 26. The preserved list must be compared with the full panel of List 14 (441/40 B.C.); there are two new payers (Anaphe and the Diakrioi of Euboea). Aegina fell out in 431 B.C., Myrina and Imbros appear in a special rubric (i. 18 f.) with partial payments. Perhaps they fell short this year; but see n. 4.

page 160 note 3 The editors now allow enough room in List 25, col. iii for the three new Hellespontine names found in IG i2. 214/15 (with 225); see ATL i. 91Google Scholar (frag. 3), 194 and 197 and contrast Meritt, , Ath. Fin. Doc., p. 7.Google Scholar The Chersonesitai and Limnaioi may have been listed with their whole tribute in the rubric of 25 (contrast 26); but this rubric may not have recurred. If we omit it the lacuna in the Hellespontine panel could be lengthened by as much as three lines. See next note. No name in List 25 takes more than one line (ATL iii, 81 f. n. 30); in 26 at least two preserved Hellespontine names fill two.Google Scholar

rubric of 25 (contrast 26); but this rubric may not have recurred. If we omit it the lacuna in the Hellespontine panel could be lengthened by as much as three lines. See next note. No name in List 25 takes more than one line (ATL iii, 81 f. n. 30); in 26 at least two preserved Hellespontine names fill two.Google Scholar

page 160 note 4 As preserved the panel in List 25 misses nine pre-war payers and one new payer known from IG i2. 216 and A9 (the Diakrioi of Euboea); Myrina and Imbros have been restored in a special panel. The editors give eleven more lines and admit a possible one or two more. I assume full payments by Myrina and Imbros this year; in 26 room could be found for complementary payments at the foot of col. ii. The rubric, however, may be wrongly restored in 25; in this list general rubrics appear at the end, after the panels (here Thracian) only rubrics concerning cities in the preceding district. Frags. 4–5 could then be moved up to shorten the gap after frags. 1–2, making ample room for Myrina, Imbros, and the three proposed new-comers in the Island panel; Sestos could be fitted in the Hellespontine panel (see n. 3). Such shifts in the disposition of the fragments of List 2 5 are clearly possible: see the epigraphic notes in ATL i. 91 ff. and especially figs. 125–6.

rubric, however, may be wrongly restored in 25; in this list general rubrics appear at the end, after the panels (here Thracian) only rubrics concerning cities in the preceding district. Frags. 4–5 could then be moved up to shorten the gap after frags. 1–2, making ample room for Myrina, Imbros, and the three proposed new-comers in the Island panel; Sestos could be fitted in the Hellespontine panel (see n. 3). Such shifts in the disposition of the fragments of List 2 5 are clearly possible: see the epigraphic notes in ATL i. 91 ff. and especially figs. 125–6.

page 160 note 5 IG i2. 222 (ATL 28) would have to be dated either 430/29 or 429/8 B.C. As a consequence the rise in Klazomenai's tribute should probably be assigned to 430, not 428 B.C.; see ATL i. 197 and 199 (for 428 B.C.).Google Scholar

page 161 note 1 iii. 136 and n. 11. See also Nesselhauf, , op. cit., p. 83,Google Scholar n. 1. West had argued (op. cit., p. 442) that ‘before the capture of the city there were no soldiers in Potideia’.Google Scholar

page 161 note 2 Thuc. 2. 79. 7, 4. 7, 6. 7. 3.

page 161 note 3 See p. 159, n. 2. This assumes my dating of IG i2 216.

page 161 note 4 See Hesp. xiii (1944), 211–29 (IG ii2. 55+): SEG x. 67. Meritt reclaimed the decree from the fourth century, enlarging and improving its text.Google Scholar

page 161 note 5 Compare D21, 4–8 with D4, 34–41 and see D3, 18 ff.:

In this context is

In this context is means ‘into the interior’ (Macedonia), not ‘into Methonean territory’; see Lenk, in P.-W. xv. 1386Google Scholar and ATL iii. 135Google Scholar against Meritt, , op. cit., p. 216.Google Scholar

means ‘into the interior’ (Macedonia), not ‘into Methonean territory’; see Lenk, in P.-W. xv. 1386Google Scholar and ATL iii. 135Google Scholar against Meritt, , op. cit., p. 216.Google Scholar

page 161 note 6 See D21, 8 ff. and 19 ff. (with the improved reading of ATL iv. x. 18):Google ScholarMeritt, , op. cit., p. 215.Google Scholar

page 161 note 7 D21, 5–8;

I adopt Meritt's plausible restorations in lines 5 and 8 (see op. cit. pp. 216 and 218)Google Scholar, but prefer his variant

I adopt Meritt's plausible restorations in lines 5 and 8 (see op. cit. pp. 216 and 218)Google Scholar, but prefer his variant

to the published

to the published

page 162 note 1 D8 (IG i2. 64 +), 21 ff. (quoted on p. 163, n. 6).

page 162 note 2 Meritt argued similarly in the context of 428 B.C. (op. cit., p. 217)Google Scholar, comparing lines 14 ff. of the Brea Decree (IG i2. 45 +: Tod no. 44):

Woodhead, A. G. (CQ xlvi [1952], 57–62)CrossRefGoogle Scholar made out a strong case for reducing the date of this decree (to c. 438 B.C.) and locating Brea in north-west Chalcidice, between Therme and Strepsa. Should the decree be brought down in fact into the Peloponnesian War, as is suggested by two minor prosopographical points noted by Woodhead (p. 62)?

Woodhead, A. G. (CQ xlvi [1952], 57–62)CrossRefGoogle Scholar made out a strong case for reducing the date of this decree (to c. 438 B.C.) and locating Brea in north-west Chalcidice, between Therme and Strepsa. Should the decree be brought down in fact into the Peloponnesian War, as is suggested by two minor prosopographical points noted by Woodhead (p. 62)?

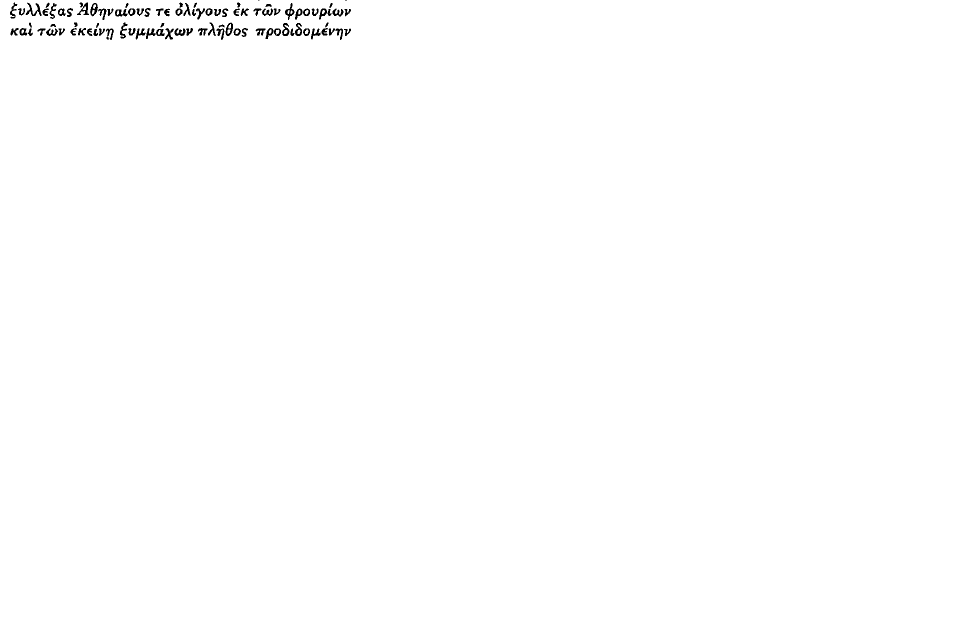

page 162 note 3 The verbs

(see p. 161, n. 7) in D21 (6 f.) show that Aphytis had to contribute towards the cost of the

(see p. 161, n. 7) in D21 (6 f.) show that Aphytis had to contribute towards the cost of the ; this must hold for Methone. See Meritt, , op. cit. cit., p. 217. The strange postscript of D21 (17 f.) may have regulated Aphytis' payments. The clear parallel with the postscript of D3 (29 ff.) led Meritt to argue that Aphytis also was granted the privilege of paying the

; this must hold for Methone. See Meritt, , op. cit. cit., p. 217. The strange postscript of D21 (17 f.) may have regulated Aphytis' payments. The clear parallel with the postscript of D3 (29 ff.) led Meritt to argue that Aphytis also was granted the privilege of paying the only; the one likely restoration is

only; the one likely restoration is

the quota on a tribute of 5 talents (pp. 220 ff.). Now if my dates for IG i2. 216 and 218 are valid, this view is virtually barred, since in the lists Aphytis is registered as paying her whole pre-war tribute of 3 talents (ATL 25. ii. 10 and 26. ii. 11); D21 could only be dated 425/4 B.C. or later.Google Scholar

the quota on a tribute of 5 talents (pp. 220 ff.). Now if my dates for IG i2. 216 and 218 are valid, this view is virtually barred, since in the lists Aphytis is registered as paying her whole pre-war tribute of 3 talents (ATL 25. ii. 10 and 26. ii. 11); D21 could only be dated 425/4 B.C. or later.Google Scholar

page 162 note 4 Thuc. 4.7:…

By 424 B.C. Perdikkas feared

By 424 B.C. Perdikkas feared

apart from Methone, he secretly helped Knemos (Thuc. 4. 79. 2 with 2. 80. 7).

apart from Methone, he secretly helped Knemos (Thuc. 4. 79. 2 with 2. 80. 7).

page 162 note 5 Abh. Berl. Akad. 1861, pp. 589 ff.Google Scholar

page 162 note 6 ATL iii. 136Google Scholar (noted already by West, , op. cit., p. 443).Google Scholar

page 162 note 7 Ibid., pp. 134 f. They appositely quote from the Kallias Decree (D2, 27 f.), where the financial quadriennium is obviously meant.

from the Kallias Decree (D2, 27 f.), where the financial quadriennium is obviously meant.

page 163 note 1 Kirchhoff first fixed on the Panathenaia, (op. cit., pp. 591 f.)Google Scholar. West's view (op. cit., p. 441)Google Scholar was originally accepted by Meritt, (Ath. Fin. Doc., pp. 22 f.)Google Scholar. Three months, West thought, would be enough for all the negotiations envisaged in D3 (till the Dionysia; line 24 f.). The ATL counter argument (for a period of about eight months) is inconclusive (p. 134 n. 6). Why should the ambassadors not travel in the winter, despite being over fifty?

page 163 note 2

Notion well illustrates the first possibility (seep. 157, n. 3).

Notion well illustrates the first possibility (seep. 157, n. 3).

page 163 note 3 Thuc. 2.29.6. See on this ATL iii. 323 ff.Google Scholar West put Methone's accession in 432/1 (op. cit., pp. 443 f.Google Scholar), the ATL date is 434 B.C. (iii. 136 and 319). My view would eliminate die postulated assessment in 428/7 B.C. The new names and quotas in IG i2. 214/15 (+225) could go back to the assessment of 430 B.C., though Lysikles and Paches may have added new tributaries, as generals did in the 430's (see ATL iii. 82 and 84 on die Thracian and p. 160, nn. 1, 3, 5, above).Google Scholar

and p. 160, nn. 1, 3, 5, above).Google Scholar

page 163 note 4 For see ATL iii. 15 f.Google Scholar For

see ATL iii. 15 f.Google Scholar For see ibid., p. 137.

see ibid., p. 137.

page 163 note 5 See ATL i. 213 and iii. 133 (witii n. 2). Significandy we find in D8, 18 ff. Google Scholar

Google Scholar

page 163 note 6 For die purpose and scope of D8 see Meritt's invaluable study in Doc. Ath. Trib., pp. 3–42.Google Scholar For Samos, etc., see D8, 21–25;

Samos had, of course, been paying war-indemnity since 439 B.C.; Thera's case was similar, as Meritt saw. He already linked the other payments with the

Samos had, of course, been paying war-indemnity since 439 B.C.; Thera's case was similar, as Meritt saw. He already linked the other payments with the of D3, 14; see op. cit., pp. 35–38Google Scholar and compare ATL iii. 334 ff.Google Scholar The supplement

of D3, 14; see op. cit., pp. 35–38Google Scholar and compare ATL iii. 334 ff.Google Scholar The supplement is strongly supported by Thuc. 1. 100. 3 (Thasos) and 117. 3 (Samos).

is strongly supported by Thuc. 1. 100. 3 (Thasos) and 117. 3 (Samos).

page 164 note 1 Despite Swoboda's, doubts (P.-W. v. 1046 ff.).Google Scholar Diodoros (12. 39. 2), unlike Plutarch (Per. 32. 1), gives no name.

page 164 note 2 See CAH v. 477 ff.Google Scholar Gomme inclined tc follow him (op. cit. ii. 184 ff.).Google ScholarJones, A. H. M. (Athenian Democracy, p. 113)Google Scholar has suggested that D3 was not drafted in Council, but proposed by an ordinary citizen in the Assembly. He makes rather too much (D3, 5 ff.): a Councilloi could surely recommend that the people ‘forthwith' decide by vote a contentious matter, if the Assembly meeting were close at hand—possibly on the same day. For D3 as a probouleuma see Meritt, , Hesp. xiii (1944), 220.Google Scholar

(D3, 5 ff.): a Councilloi could surely recommend that the people ‘forthwith' decide by vote a contentious matter, if the Assembly meeting were close at hand—possibly on the same day. For D3 as a probouleuma see Meritt, , Hesp. xiii (1944), 220.Google Scholar

page 164 note 3 2. 59. 1–2 and 65. 2–4 suggest a limited direct attack on Pericles himself. There is not a word about slanders, though, as Gomme points out (op. cit. iii. 660 f.),Google Scholar Thucydides freely reports those issued against Kleon and Alcibiades. For Gomme Thucydides' silence is deliberate (op: cit. ii. 184).Google Scholar

page 164 note 4 For the plague's effects see Thuc. 2. 48. 4 and 53 (in some it bred ); for the

); for the see 2. 17. 1–2 and 21. 3 with 54. The plague's second onset came precisely in winter 427/6 B.C. (3. 87. 1–2). Diagoras of Melos may have been prosecuted then (see Clouds 830 and P.-W. v. 310 f.Google Scholar), under the bill of Diopeithes impeaching

see 2. 17. 1–2 and 21. 3 with 54. The plague's second onset came precisely in winter 427/6 B.C. (3. 87. 1–2). Diagoras of Melos may have been prosecuted then (see Clouds 830 and P.-W. v. 310 f.Google Scholar), under the bill of Diopeithes impeaching

For its wording compare Clouds 225–30 and 243–53.

For its wording compare Clouds 225–30 and 243–53.

page 164 note 5 D4, 47–51. Pleistias' embassy (the first ' mentioned) would be that appointed by D3, 16 ff.

page 164 note 6 D4, 34–47 (quoted in part on p. 162).

page 165 note 1 For Perdikkas and the pretenders in the period from c. 432 to 423 B.C. see P.-W. xix. 594–8Google Scholar (Geyer). Methone challenged Perdikkas' right to move troops through its territory (D3, 22 f.); in ATL iii. 329 and n. 81 this is acutely linked with the operations against the pretender Derdas. The notorious embassy of Philocrates (Dem. 19. 150–81) was away no more than three months in all.Google Scholar

page 165 note 2 The embassy to Persia in the Achamians (it left Athens in 437/6 B.C.!) was held up there for eight months until the king's return with his army and then feasted royally (Ach. 65 ff. and 80–89). That sent to Thrace was snowbound and spent the winter in drinking bouts with Sitalkes (136–50).Google Scholar

- 5

- Cited by