No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

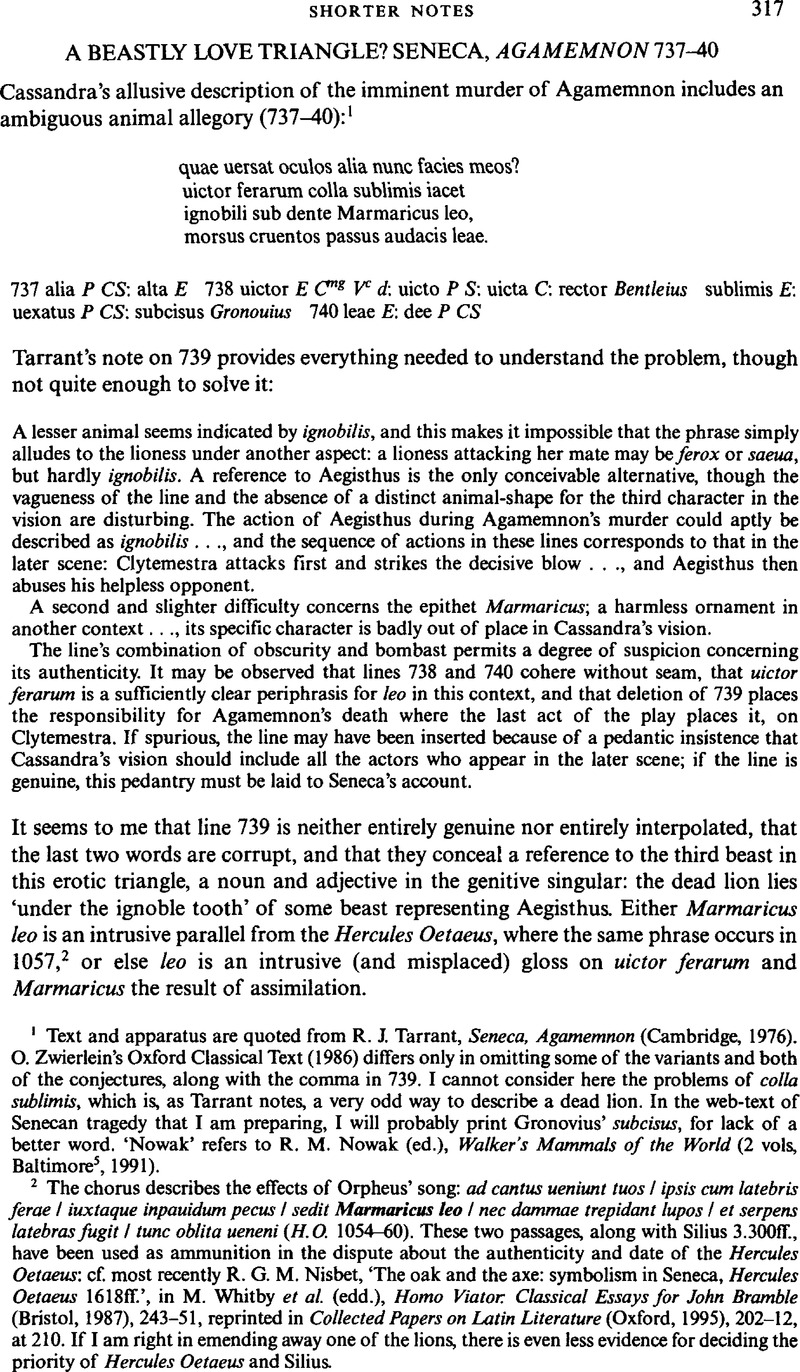

A beastly love triangle? Seneca, Agamemnon 737–40

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Shorter Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 2000

References

1 Text and apparatus are quoted from Tarrant, R. J., Seneca, Agamemnon (Cambridge, 1976).Google Scholar O. Zwierlein's Oxford Classical Text (1986) differs only in omitting some of the variants and both of the conjectures, along with the comma in 739. I cannot consider here the problems of colla sublimis, which is, as Tarrant notes, a very odd way to describe a dead lion. In the web-text of Senecan tragedy that I am preparing, I will probably print Gronovius’ subcisus, for lack of a better word. ‘Nowak’ refers to Nowak, R. M. (ed.), Walker's Mammals of the World (2 vols, Baltimore, 1991).Google Scholar

2 The chorus describes the effects of Orpheus’ song: ad cantus ueniunt tuos / ipsis cum latebris ferae / iuxtaque inpauidum peats / sedit Marmaricus leo / nec dammae trepidant lupos / et serpens latebras fugit / tune oblita ueneni (H.O. 1054–60). These two passages, along with Silius 3.30Off., have been used as ammunition in the dispute about the authenticity and date of the Hercules Oetaeus: cf. most recently Nisbet, R. G. M., ‘The oak and the axe: symbolism in Seneca, Hercules Oetaeus 1618ff.’, in Whitby, M.et al. (edd.), Homo Viator Classical Essays for John Bramble (Bristol, 1987), 243–51Google Scholar, reprinted in Collected Papers on Latin Literature (Oxford, 1995), 202–12, at 210. If I am right in emending away one of the lions, there is even less evidence for deciding the priority of Hercules Oetaeus and Silius.

3 It is certainly far better known as a scavenger of human corpses, from the fourth line of the Iliad on.

4 This would be a highly unnatural sort of hunt for a lioness, but the idea that a hyena would dine on the leftovers should raise no eyebrows. They are superb scavengers, and have the ability ‘quickly to eat and digest entire carcasses, including skin and bones’ (Nowak 2.1179; so also Ctesias, quoted in Diodorus Siculus 3.35.10). I should perhaps note that they are also competent hunters, and their reputation as parasites of the lion is not entirely deserved. As Nowak puts it, ‘[ajlthough the spotted hyena is sometimes said to be a scavenger of the lion, most dead prey on which both hyenas and lions were seen feeding [in a particular study] had been killed by the hyenas’(2.1180).

5 There are curious differences between ancient and modern explanations of this belief. Aristotle (H.A. 6.31, 579b 16–27) says that both sexes appear to have female characteristics, while Nowak (2.1179) says that both sexes appear to be male: ‘The external genitalia of the female so closely resemble those of the male that the two sexes are practically impossible to distinguish in the field’—I omit the anatomical details. The gender monomorphism of the hyena is no doubt what gave rise to the ancient belief, as apparent males turned up pregnant. Perhaps I should add that only the spotted hyena, Crocuta crocuta, appears androgynous, so the OLD's restriction of the definition of Latin hyaena to the striped hyena, Hyaena hyaena, is at best over-narrow.

6 Bömer, F., P. Ovidius Naso, Metamorphosen XIV-XV (Heidelberg, 1986)Google Scholar, ad loc., cites these two and five others, and implies that he might have given more.

7 These are Keller, O., Antike Tierwelt (2 vols., Leipzig, 1909–13), 1.152ffGoogle Scholar; RE Supp. IV, 762, 53–56; A. Ernout (ed.), Pline L'Ancien, Histoire naturelk. Livre VIII, ad loc. It is conceivable that Aeschylus’ wolf (quoted above) is a hyena, though the latter is not actually attested before Herodotus (4.192). It is worth noting that the striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena) has a mane, while the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) has none. That might explain what the lioness is doing in the family tree: to the unscientific observer, a maned hyena might be a plausible offspring of a union between a maneless dog-shaped hyena and a maned lion—not that lionesses have manes, of course, but they can presumably pass them on to their sons. The two species are otherwise fairly similar in overall appearance (Nowak provides pictures). If this hypothesis is correct, the names have been reversed, with ancient hyaena = modern Crocuta crocuta (spotted) and ancient corocotta = modern Hyaena hyaena (striped).

8 The others are Ctesias (n. 4) and Artemidorus, quoted in Strabo 16.4.18f.

9 It is an even better description of the jackal, which is just a smallish wolf. Dogs, wolves, jackals, and coyotes form the genus Canis of the family Canidae, while hyenas form a separate family (Hyaenidae) in the order Carnivora, and are thought (Nowak 2.1177) to have evolved from a branch of the Viverridae (mongooses and other less familiar animals). Nevertheless, to the unscientific observer, hyenas are just ugly hump-backed scavenger dogs with unusually powerful jaws.

10 I can quote no parallel, though I have not attempted to examine every instance of canis and lupus in Latin literature, or of κωυ and λκoς in Greek, to see which might be construed as hyenas or jackals.

11 The adjective must be specific to give a pointer to the species, but that in itself allows the noun to be more generic.