No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

AmΦIΣbhthΣiΣ TiΣ (Aristotle, E.N. 1096b7–26)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

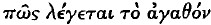

E.N. 1. 6 may be divided into three approximately equal paragraphs. The first of these (A) contains four arguments against Academic positions associated with the phrase ‘Idea of the Good’. All these arguments also occur, together with others, in the Eudemian Ethics. The second paragraph (B) consists of the consideration and rejection of an objection to the whole or a part of A, and is new to E.N. The third (C), also new to E.N., consists of the putting forward and dismissal of two alternative answers to the question  ;—answers different, presumably, to that or those rejected in A.

;—answers different, presumably, to that or those rejected in A.

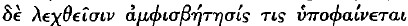

My concern is with B. This paragraph is linked with A by the words

, ‘a controversy can just be seen in what has been said’. These words, referring back to arguments that appear also in E.E., suggest to me that the objection Aristotle is about to discuss is one that had actually been brought against those arguments, after they had been delivered in their Eudemian or some other earlier form, by an opponent who might have belonged to the Academy, but might equally well have belonged to the Lyceum itself. For ease of exposition, I shall in what follows assume this to be the case, and shall refer to the author of the objection as the Objector. This assumption is not, however, essential to the main argument of this article.

, ‘a controversy can just be seen in what has been said’. These words, referring back to arguments that appear also in E.E., suggest to me that the objection Aristotle is about to discuss is one that had actually been brought against those arguments, after they had been delivered in their Eudemian or some other earlier form, by an opponent who might have belonged to the Academy, but might equally well have belonged to the Lyceum itself. For ease of exposition, I shall in what follows assume this to be the case, and shall refer to the author of the objection as the Objector. This assumption is not, however, essential to the main argument of this article.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1966

References

page 55 note 1 An earlier version of this paper was read to the Scots Ancient Philosophy Group on 18 Apr. 1964.

page 55 note 2 I shall refer to parts of the chapter as follows:

A 1 1096a17–23 = c. 6 § 2

A 2 a23–29 = § 3

A 3 a29–34 = § 4

A 4 a34–b5 = §§ 5–6

B b7–26 = §§ 8–11

C b2–1097a14 = §§ 12–16

page 55 note 3 I argue for this assumption in the Appendix to this article.

page 56 note 1 The reminiscence falls short of actual quotation; e.g. the Greek for ‘for its own sake’ is, in Plato's exposition, ![]() (twice),

(twice), ![]() (once),

(once), ![]() (twice), but not

(twice), but not ![]() as in Aristotle. The verbs in Plato are

as in Aristotle. The verbs in Plato are ![]() (twice),

(twice), ![]() (twice),

(twice), ![]() (once),

(once), ![]() (once); in Aristotle

(once); in Aristotle ![]() (3 times),

(3 times), ![]() (once). Nevertheless the reminiscence is probably intended, and the list of examples that Aristotle gives in the course of his reply to the objection follows Glaucon's list very closely.

(once). Nevertheless the reminiscence is probably intended, and the list of examples that Aristotle gives in the course of his reply to the objection follows Glaucon's list very closely.

page 56 note 2 Gauthier, R. A., AND Jolif, J. Y.: L'Éthique à Nicomaque, 3 vols. Louvain, 1959.Google Scholar

page 56 note 3 Simplicius, , In Ar. Cat. p. 63, 22–29.Google Scholar

page 57 note 1 Prof. D.J. Allan, in ‘Aristotle's Criticism of Platonic Doctrine concerning Goodness and the Good’ (Proc.Ar.Soc. 1963–4,273–86), discusses the question of the relation between E.N. i. 6 and E.E. 1. 8, and reaches similar conclusions to mine, though he does not, as I do, assume the priority of E.E.

page 57 note 2 I owe this suggestion to an unpublished lecture by Mr. R. M. Hare.

page 58 note 1 The ‘writings and utterances’ I have in mind are the Republic (perhaps especially 504 e–509 c, the Parable of the Sun) and such lost writings and utterances as may have contained substantially the same theory of the Idea of the Good as the Republic contains. I do not suppose that Plato himself was propounding the Weak Platonic Theory in the Republic—nor the Strong Platonic Theory either. The distinctions that differentiate these two theories from each other long postdate the writing of the Republic. What I am supposing is that a student some twenty years after Plato's death might (a) regard the arguments of the Republic as tending to establish the W.P.T., so that Aristotle's arguments against that theory in para. A could be regarded as an attack on the Republic, and (b) regard his own particular version of the W.P.T., i.e. the one that I shall reconstruct from B, as a plausible interpretation of what Plato wrote.

page 58 note 2 For examples see Met. Z 8, H 2.

page 58 note 3 The Right and the Good, pp. 121–3.

page 58 note 4 The Language of Morals, pp. 80 fF.

page 58 note 5 I take ![]() here to mean ‘technique for discovering’ rather than ‘technique for producing’. Both are possible senses in Aristotle, but the latter is implausible in this context: there are many techniques, for example, for producing whiteness in different things, though that is undoubtedly an

here to mean ‘technique for discovering’ rather than ‘technique for producing’. Both are possible senses in Aristotle, but the latter is implausible in this context: there are many techniques, for example, for producing whiteness in different things, though that is undoubtedly an ![]() . This conclusion is borne out by Aristotle's taking

. This conclusion is borne out by Aristotle's taking ![]() as an example. The general and the physician show their skill in recognizing the right occasion rather than in producing it.

as an example. The general and the physician show their skill in recognizing the right occasion rather than in producing it.

page 59 note 1 This is a necessary condition of classifying things into kinds and referring to them by a common name; for if there were two mutually independent methods for determining whether, e.g., something was white, what reason would one have for supposing that whiteness as determined by one method was the same property as whiteness as determined by the other method?

page 60 note 1 Those familiar with modern moral philosophy will recognize that the Form of the Good (on this account) is more or less identical with G. E. Moore's non-natural property of intrinsic goodness (Principia Ethica, ch. i §§ 15 ff.).

page 64 note 1 This is true of my own usage, though some of my colleagues deny that the word carries for them the implication that actual controversy has taken place.