Article contents

Two Textual Problems in Euripides' Antiope, Fr. 188

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

In a recent article I drew attention to the fact that the well-known fable of the improvident cicada and the industrious ant has a close resemblance to the story of the twin brothers Amphion and Zethus and their classic debate on the respective merits of the artistic and practical life in Euripides' Antiope, which is reflected not only in the argument of Callicles and Socrates in the Gorgias and Horace, Ep. i. 18

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1967

References

1 ‘A Grasshopper's Diet’, C.Q. N.s. xvi (1966), 111.Google Scholar

2 Valckenaer's emendation. Wecklein, (Philologus lxxix [1923], 59)Google Scholar proposed ![]() .

.

3 Dodds, , Gorgias, p. 278.Google Scholar Cf. Schaal, , De Euripidis Antiopa [Diss. Berlin 1914], p. 19:Google Scholarsed quo iure zethus fratrem hortatur, ut bellis gerendis et bellicarum rerum studio se det? Nec venatio ![]() dici potest. (I cannot, however, agree with Schaal that Plato's

dici potest. (I cannot, however, agree with Schaal that Plato's ![]() was also in the text of Euripides.) For Zethus' agricultural pursuits, see especially the play summary (?) of Apollodorus (3. 5. 5) Z.

was also in the text of Euripides.) For Zethus' agricultural pursuits, see especially the play summary (?) of Apollodorus (3. 5. 5) Z. ![]() and the assumptions inherent in the Horatian parallel (Ep. 1. 18. 40, 45–46) and in Varro's Onos lyras fr. 14, in so far as this draws on Amphion-Zethus material. Propertius (3. 15. 41) refers to his prata.

and the assumptions inherent in the Horatian parallel (Ep. 1. 18. 40, 45–46) and in Varro's Onos lyras fr. 14, in so far as this draws on Amphion-Zethus material. Propertius (3. 15. 41) refers to his prata.

1 Kritische Studien, ii. 448.Google Scholar Nauck himself suggested ![]() to which Dodds gives qualified approval, but Plato's Trpayiidriav suggests that the original was an abstract rather than a personal noun.

to which Dodds gives qualified approval, but Plato's Trpayiidriav suggests that the original was an abstract rather than a personal noun.

2 In such admonitions with ![]() the second imperative is usually introduced by the adversative

the second imperative is usually introduced by the adversative ![]() , except in cases like Ar. Vesp. 652, Eq. 821, Ran. 843, where the second verb is negatived. But cf. Theopompus fr. 62

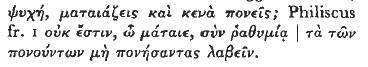

, except in cases like Ar. Vesp. 652, Eq. 821, Ran. 843, where the second verb is negatived. But cf. Theopompus fr. 62 ![]()

![]()

3 Note also the contrast (in a not dissimilar theme) of Spartan ![]() and Athenians

and Athenians ![]() in Pericles' funeral speech (Thuc. 2. 39). In the metaphorical use of

in Pericles' funeral speech (Thuc. 2. 39). In the metaphorical use of ![]() the musical metaphor and its moral implications are seldom entirely absent; in Thuc. 5. 9, if

the musical metaphor and its moral implications are seldom entirely absent; in Thuc. 5. 9, if ![]() be read, it is explicit.

be read, it is explicit.

4 Cf. frr. 233, 236, 238, 239, 240.

1 Schaal, (op. cit., p. 14)Google Scholar may be right in thinking that Olyrapiodorus knew the Antiope only through Plato scholia. And certainly his ![]() of Zethus suggests unfamiliarity with the background of the story, which might have been enhanced if he thought

of Zethus suggests unfamiliarity with the background of the story, which might have been enhanced if he thought ![]() was what Zethus recommended.

was what Zethus recommended.

1 Especially in Horace—see Wickham on C. 3. 24. 40. Amphion's rejection of wealth is referred to also in fr. 1 g 1.

2 Dodds, , op. cit., p. 279;Google ScholarSnell, , Scenes from Greek Drama, p. 86Google Scholar—referring to Wilamowitz, , Platon, ii. 375.Google Scholar But the proposal was made long before by Routh in his edition of the Gorgias (1784), p. 436.Google Scholar

3 I am grateful to Dr. W. S. M. Nicoll for drawing my attention to this.

4 e.g. Sen, . Ep. 48. 9Google Scholardebilitari generosam indolem in istas argutias (sc. diabeticorum) coniectam. (This closely resembles the corruption of the ![]() man in the Gorgias and the Antiope debate.)

man in the Gorgias and the Antiope debate.)

5 It seems to be the standard one—cf. Hsch. ![]() , etc.

, etc.

1 It is Zethus who is traditionally durus, Amphion mollis (Prop. 3. 15. 29).

1 On Socrates' ![]() , cf. also Lib. Decl. i. 127. In Plat. Ap. 23 c he admits that those who like to listen to his elenchus are

, cf. also Lib. Decl. i. 127. In Plat. Ap. 23 c he admits that those who like to listen to his elenchus are ![]()

![]() Cf. Xen, . Smp. 4. 44.Google Scholar

Cf. Xen, . Smp. 4. 44.Google Scholar

1 As both this letter and Horace's epistle to Lollius draw on the Antiope, another similarity may be noticed: Jul. ![]()

![]()

![]() : Hor. quamvis nil extra numerum fecisse modumque curas (59–60).

: Hor. quamvis nil extra numerum fecisse modumque curas (59–60).

2 Rearranged as a trimeter with the help of Philostr. V.A. 7. 34, the last words contitute Eur. fr. 192. ![]() which Julian virtually equates with

which Julian virtually equates with ![]() , appears to mean ‘time to devote exclusively to one's art’.

, appears to mean ‘time to devote exclusively to one's art’.

3 For similar variation of meaning, cf. Eng. dally, now mostly used of idle or frivolous delay or trifling, but from Old French dallier = ‘converse’, and in earliest English usage meaning ‘talk or converse lightly or idly’ (O.E.D.); and the Scots verb haver, which means ‘talk foolishly’, but is often misused (by Englishmen) as if meaning ‘hesitate’.

4 Cf. Philo, , De Somn. i. 255Google Scholar![]()

1 In view of this traditional association of the life of the cicada there is a certain irony in Theocritus' line (7. 139) ![]()

![]()

- 3

- Cited by