Since becoming the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 2012, Xi Jinping 习近平 has pushed an agenda of reviving the memory of the “Chinese people's war of resistance against Japanese aggression and the world anti-fascist war,” as the Second World War is officially known in China. Within three years of taking office, Xi had extended the war's time frame from eight to fourteen years, overseen an unprecedented military parade at Tiananmen Square and established two new official remembrance days. The decision of the National People's Congress in 2014 to designate 13 December as a national day of commemoration of the Nanjing Massacre – when Japanese imperial troops slaughtered and raped thousands of citizens of China's then capital and pillaged the city in a six-week killing spree – raised eyebrows across the world, not least in Japan, where officials questioned Beijing's renewed interest in Japan's wartime conduct.Footnote 1

The official Chinese discourse of national humiliation and victimization, accompanied by a political “numbers game” aimed at quantifying and denouncing Japanese war atrocities, emerged during the late 1990s and early 2000s as a paradigm of Chinese war remembrance, replacing the discourse of the Maoist era.Footnote 2 Despite the notable shifts in China's commemorative practices in recent years, the “national victimization” paradigm has continued to function as the standard interpretative framework in the academic literature, coupled with a predominant focus on the Nanjing Massacre as the quintessential event of China's war remembrance.Footnote 3

Given the country's evolving global status, ambitions and pretentions, some authors have asked recently whether it is still fitting for the Chinese leadership to espouse such a passive and powerless victimhood discourse.Footnote 4 The present study suggests that this question overlooks a paradigm shift which has underpinned the recent wave of commemoration under Xi Jinping. This shift comprises a centrally planned and implemented move away from the earlier victimization narrative towards a new, more powerful retelling of the history of the Second World War. I use three representative cases to argue that elements of the two earlier paradigms have been repackaged and remixed into a unifying and empowering new reading that emphasizes national victory and national greatness, thereby reflecting China's changed place in international society and the CCP's evolving policy goals.

The basic parameters of this shift were first outlined by Xi during a Politburo meeting held on 31 July 2015 to review the history of China's War of Resistance. The purpose of the review, as explained by Xi, was to acknowledge the “great contribution” made by the Chinese people towards victory in the Second World War and hence towards international peace and justice, and to affirm that the Chinese people should “never forget the past” and “create a positive attitude for the future.”Footnote 5 During the meeting, Xi observed that research on the war remained far from adequate, given the war's “historical significance” and its “influence on the Chinese nation and the world.” Urging historians to study the 14-year war as an integrated whole, he called on them to focus on three core aspects: the “great significance” of the Chinese people's war, its “important place” in the global fight against fascism, and the “central role” of the CCP as the “key” to ultimate victory. As if to respond to his own call, Xi then provided an assessment of the historical significance of the war, stating that it “re-established China's status as a great power in the world, won the Chinese people the respect of peace-loving people of the world, [and] opened up the prospect of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”Footnote 6

This assessment would form the core of subsequent public commemorations and representations of the war. The remarkable rhetorical changes reflected in these representations point at a carefully conceived and systematically implemented decision not only to bring the official narrative on the Second World War into line with Beijing's present aims and ambitions but also to target these more effectively to domestic, regional and global audiences. This article examines how this top-down project has since taken shape. It focuses on three cases, drawn from the school curriculum, museum exhibitions and formal diplomacy, each of which is analysed in accordance with a basic framework identifying the major themes, seats of agency, dichotomies and historical “lessons.” Before analysing these three cases, however, the next section puts the latest developments into relief by outlining the two preceding paradigms using a similar basic frame of analysis.

War Remembrance before Xi: Two Interpretative Paradigms

The development of Second World War discourse in the People's Republic of China (PRC) reflects the complex evolving relationship between the CCP and Chinese society.Footnote 7 This section draws from the available literature to outline the two narrative paradigms that most scholars agree shaped official war remembrance in China from 1949 until the beginning of the current millennium. This review provides the key points of reference for the assessment of the more recent instances of Second World War commemoration discussed in the subsequent sections of this article.

Revolutionary heroism

The first paradigm characterized the official discourse on the Second World War during the Maoist years, when Beijing was engaged domestically in ideological campaigns and globally with exporting the Socialist revolution. According to this narrative, the CCP single-handedly led the Chinese people to victory in a war waged not against the Japanese nation as such, but rather against a ruling clique of Japanese militarists aided by Chinese feudalist traitors – that is, the diehard Chinese Nationalists (Kuomintang or KMT) coalescing around Chiang Kai-shek 蒋介石.Footnote 8 The war was thus presented as a transnational struggle between progressive and reactionary forces, based on a dichotomy juxtaposing the CCP's revolutionary fervour, heroism and triumph with KMT callousness, cowardice and defeatism, and leaving little room for recalling Chinese victimhood or Japanese atrocities.Footnote 9 With resistance and collaboration framed almost exclusively along partisan-political lines, the main agency in this metanarrative was vested in the CCP as the vanguard – leader, tutor and liberator – of the Chinese people. The war itself thus had little inherent significance, featuring in Chinese historiography as a “mere way-station on the path to CCP dominance in 1949.”Footnote 10 If there was a lesson to be learned from the war, it was evoked in Mao's observation in April 1945 that “without the efforts of the CCP and without the CCP as the mainstay of the Chinese people, China's independence and liberation would not have been possible.”Footnote 11 It is this message that shaped the main narratives in “Red” heritage sites and museums across the country, such as the Revolutionary Memorial Hall in Yan'an 延安 (the de facto CCP capital during the Second World War) and the former Museum of the Chinese Revolution (now the National Museum) in Beijing, founded in the 1950s and early 1960s. The emphasis on revolution in these historical representations was so pervasive that public memory of the war itself had virtually disappeared in China by the time of Mao's death in 1976.Footnote 12 Aside from domestic politics, there were also geopolitical motives – for example, mollifying Tokyo to balance Washington and Moscow – for the CCP leadership to avoid nationalist retellings of the war and promote what James Reilly has termed a “benevolent amnesia.”Footnote 13

National victimization

While the “revolutionary heroism” theme never disappeared from Chinese Second World War discourse, there is broad consensus that it was supplanted as the central paradigm in the late 1980s by a nationalistic metanarrative depicting the Chinese nation as the victim of a long series of hostile interventions by foreign states, culminating in Japan's invasion of (parts of) China between 1931 and 1945.Footnote 14 This paradigm shift has been understood as a response both to the ideological vacuum and credibility crisis that the CCP suffered domestically in the wake of several disastrous political campaigns and the Tiananmen Square protests, and also to the geopolitical recalibration prompted by the collapse of the Soviet Union. As Tokyo lost its strategic value to Beijing as a de facto ally against Moscow, and the CCP reverted to nationalism to shore up its floundering claims to legitimacy, Japan became the new national nemesis, taking on the role of the external “other” in China's new identity politics.Footnote 15 The theme of national victimization and suffering at the hand of the Japanese was at the heart of the “patriotic education campaigns” that pervaded schools and museums across the country.Footnote 16 This state-led nationalism at home went hand in hand with a fervent “apology diplomacy” in the international sphere aimed at extracting political concessions from Japan.Footnote 17

The aggressor–victim dichotomy that characterized the “new remembering” implied a shift of agency away from the CCP to “evil Japan,” with the Chinese people now being represented as passive and powerless.Footnote 18 On the flip side, it gave rise to a much more benign view of the Chinese Nationalists, who were now regarded as fellow victims and martyrs instead of traitors.Footnote 19 This culminated in 2005 with President Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 publicly commemorating four high-ranking Nationalist generals, recalling their sacrifice on China's Second World War battlefields and putting them on an equal footing with four fallen CCP heroes.Footnote 20 This reconciliatory attitude towards the Kuomintang and other pan-Blue groups in Taiwan aligned well with Beijing's geostrategic considerations during the reform and opening-up era, which were premised in part on promoting cross-Strait cooperation and exchange.

The victimhood narrative is most strongly associated with historical sites of major wartime atrocities, notably in the former Nationalist capital Nanjing and in north-east China, where the Japanese military conducted biological and chemical warfare experiments on Chinese civilians. During the 1980s and 1990s, several museums and remembrance halls sprang up in the north-east, including the Memorial Hall of the Victims of the Nanjing Massacre and the Unit 731 Museum in Harbin. The key historical “lesson” propounded by these representations, and reinforced by Chinese media reports and academic publications, was that China's war experience must be remembered in order to counter the efforts of right-wing political forces in Japan to whitewash history and jeopardize global peace.Footnote 21

War Remembrance under Xi: Three Cases

On 3 September 2015, world leaders and global audiences watched as Xi delivered a 12-minute televised address from the rostrum of the Tiananmen Gate to commemorate the 70th anniversary of V-J Day.Footnote 22 As presaged in his remarks at the Politburo meeting six weeks before, Xi's speech differed from those of his predecessors in a number of significant ways. A first major departure was the strong emphasis on China's victory. In the first half of his speech, Xi used the word “victory” (shengli 胜利) 12 times, often in combination with the words “great” (weida 伟大) and the “Chinese people” (Zhonguo renmin 中国人民). In stark contrast to Jiang Zemin's 江泽民 address in 1995 and that of Hu Jintao in 2005, there was no mention of the Nanjing Massacre or any other Japanese atrocities.Footnote 23 Where Xi did refer to China's “national sacrifice,” this served solely to underline the unity and courage displayed by the unyielding Chinese people in winning “total victory.” Another striking aspect was the explicit link that Xi made between the history of the war and contemporary politics. This was done by framing China's hard-won victory as a historical anchor point not just of China's national “rejuvenation” but also of Beijing's current efforts to contribute CCP-styled concepts of governance to the international system, including the “community of common destiny for mankind” and “win-win cooperation.” This section examines how Xi's historical reinterpretation and discursive innovations are being disseminated and implemented through the school curriculum, museum exhibitions and formal diplomacy.

School curriculum: revision of middle-school history textbooks

History textbooks aim to convey the essential lessons of history to new generations and hence are an “ideal medium” for transmitting political propaganda and fostering patriotic sentiment.Footnote 24 In China's authoritarian system, the teaching materials used by primary and secondary schools must not only reflect “the will of the CCP and the state” but also, according to recently amended regulations, “guide students to become bearers of the great responsibility of rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”Footnote 25 To this end, history textbooks are standardized and unified under the auspices of the state.Footnote 26 In July 2017, the main publishing house of the Ministry of Education, the People's Education Press, issued a new history textbook for the second grade of middle schools nationwide, replacing the previous 2013 edition.Footnote 27 The book covers China's modern history, from the First Opium War through to the “liberation” of 1949, in eight units. Unit six, which comprises five chapters (lessons), is dedicated exclusively to the 14-year history of China's War of Resistance. As the principal author, Huang Yunlong, notes in an introduction published in the journal Lishi jiaoxue 历史教学, the unit on China's war history is the most elaborate one (fenliang zui zhong 分量最重) in the book.Footnote 28

The five chapters in this unit are organized thematically, presenting a coherent and compelling narrative that nonetheless proceeds in roughly chronological order. Thus, chapter 18 deals with the first six years, from the Manchurian incident of 1931 to the Xi'an incident of 1936; chapter 19 with the Marco Polo Bridge Incident and the outbreak of full-scale war in July 1937; chapter 20 with resistance at China's main battlefronts; chapter 21 with resistance behind the frontlines; and chapter 22 with final victory. Both this thematic arrangement and the substantive contents of the lessons are significant departures from previous editions.Footnote 29 The primary aim of the overhaul, as Huang points out, was to highlight four key points: (1) the 14-year history of the War of Resistance should be viewed as a whole; (2) the CCP served as the mainstay of national unity and resistance by the Chinese people; (3) the Chinese battleground was the main eastern battlefield of the Second World War; and (4) the fighting at the frontlines (mainly by the KMT) and behind the frontlines (mainly by the CCP) reinforced each other and jointly constituted China's war effort.

Along with other elements of the narrative, these four points correspond closely to the innovations put forward by Xi Jinping at the July 2015 Politburo meeting and on various subsequent occasions. Particularly notable are the overwhelming emphasis on China's “great victory” and the corresponding lack of attention to Chinese victimhood and suffering. Chapter 19 does contain a passage on the Nanjing Massacre, citing (and illustrating) some of the most ghastly war crimes committed by Japanese troops during their invasion of the city, but it does not elaborate or provide any quantifications other than a single reference to the death toll of “over 300,000,” as established in 1946 by the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal.Footnote 30 All in all, the five chapters contain very few references to Japanese atrocities, completely disregarding, for example, the testing of biological and chemical weapons on Chinese prisoners in north-east China or the protracted air raids on China's war capital, Chongqing.

Instead, the narrative goes to great lengths to emphasize Chinese military successes. These include key wins by the CCP's Eighth Route Army, such as the “smashing victory” (dajie 大捷) at Pingxingguan 平型关 in September 1937. This event is portrayed as a pivotal moment in China's resistance, marking the end of the myth of Japanese invincibility and hence – along with other CCP successes in (guerrilla) warfare – laying the foundation for ultimate victory.Footnote 31 Also included, however, are accounts of successes and bravery that had been previously omitted from mainland Chinese textbooks: those led by Nationalist troops engaged in conventional warfare at the front, such as the Battle of Wuhan (1938) and the Third Battle of Changsha (1944).Footnote 32 Subtle shifts of agency in the way the narrative deals with these feats of bravery ensure that the key role of the KMT goes unacknowledged: whereas victories in China's occupied areas are attributed plainly to the CCP, successes in major battles on the frontline were scored by the “Chinese military” (Zhongguo jundui 中国军队). Only when recounting failure, defeatism or dubious judgement – such as the abandonment of Nanjing on the eve of the massacre, Wang Jingwei's 汪精卫 betrayal, and Chiang's decision in June 1938 to flood the Yellow River – does the text explicitly mention the Nationalists.Footnote 33

The historiographical device facilitating this fluid but generally inclusive form of Chinese agency is the rehabilitation of the Second United Front.Footnote 34 This wartime KMT–CCP pact was formed in the summer of 1937 following years of continued pressure from patriotic forces across the country, including the Communists. Consigned to oblivion during the Maoist years, the Second United Front now features in Chinese historiography as a major achievement of the CCP and the principal cause of ultimate victory. The key “lesson” of China's war history, spelled out in chapter 22 of the textbook, is thus firmly tied to the root causes of victory: the war caused a national awakening; the CCP accomplished unprecedented national unity; and the resultant resistance by the Chinese people led to Japan's defeat.Footnote 35 In other words, the CCP was not the sole agent of Chinese victory, which can be credited to the Chinese nation as a whole, including rival domestic groups. But without the CCP, China's war effort would have collapsed long before victory could be achieved. Mention of Chinese wartime collaboration and KMT–CCP rivalry is confined to brief, passing references.Footnote 36 Rather than ignoring or disputing KMT successes, the CCP is thereby able to claim them as their own.

As inclusive and domestically empowering as the narrative might be in recounting the Chinese war effort, it is decidedly exclusive in how it deals with the international aspects of the war. The Allies barely feature in the narrative, except when they suffer defeats (such as in early 1942) or when there is no alternative but to acknowledge the role of the major powers (mainly the US and Britain).Footnote 37 Even when they are mentioned, the emphasis is on how these “peace-loving countries and peoples” came to support China's just cause. In this highly China-centred account, devoid of transnational perspectives or comparison (but also of empathic forms of “othering”), the Chinese people reciprocated this foreign support by fighting the Japanese in British Burma (between 1942 and 1945) and pinning down the great majority of Japan's fighting force on Chinese soil throughout the war, thereby “greatly contributing” to the global anti-fascist war and to global peace.Footnote 38

Museum exhibitions: overhaul of China's national resistance war museum

Museums are important institutions for the CCP through which it attempts to shape public memory in the service of Party legitimacy and national unity.Footnote 39 The PRC Law on the Protection of Cultural Relics, last amended in 2015, stipulates that exhibitions of cultural relics are to “strengthen the propaganda and education of the splendid historical culture and revolutionary traditions of the Chinese Nation.”Footnote 40 According to Kirk Denton, the Chinese party-state uses museums to assert changes in domestic policy and to present positive images, both to the Chinese people and to foreigners.Footnote 41 Some scholars have recently turned away from state-centred perspectives and official narratives in studying China's museums, highlighting instead the agency of non-state actors and the growing cultural and social diversity of museum curation.Footnote 42 This trend, however, should not be taken as an indication of waning state control. On the contrary, the CCP continues to exert a profound influence over China's museum exhibitions, particularly where historical narratives are involved.Footnote 43 If anything, the Party's grip on these narratives has tightened in recent years. In 2018, it issued guidelines for enhancing the protection and utilization of “revolutionary” cultural relics nationwide. With a view to “carrying out patriotic education, cultivating socialist core values and realizing the great rejuvenation,” the guidelines provide for increased central coordination and oversight of subnational representations of several pivotal events in China's revolutionary history, including the War of Resistance against Japan.Footnote 44

The primary site for studying official Chinese narratives on the Second World War is the Museum of the War of Chinese People's Resistance against Japanese Aggression (Zhongguo renmin kang-Ri zhanzheng jinianguan 中国人民抗日战争纪念馆). It is a first-grade national museum (guojia yiji bowuguan 国家一级博物馆) located in the Chinese capital and the only official facility in the country to commemorate the entirety of the war, thus effectively serving as the national centre for remembering China's War of Resistance.Footnote 45 Targeting domestic as well as international audiences, its function is to serve as a patriotism education base, a historical research centre and both a “window for non-governmental exchanges with foreign countries and a bridge to connect with compatriots in Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan and overseas Chinese.”Footnote 46 Ten years after its founding in 1987, the museum was included in the first batch of “National patriotism education and demonstration bases” (Quanguo aiguozhuyi jiaoyu shifan jidi 全国爱国主义教育示范基地), which are tasked with promoting national unity and territorial integrity under the auspices of the CCP Central Propaganda Department.Footnote 47 The museum operates directly under the auspices of the Beijing propaganda department and serves as a major “Red tourism” base in the city, receiving large numbers of cadres and school children among its million-plus annual visitors.Footnote 48 In July 2014, Xi Jinping presided over a high-profile, nationally televised commemoration service held at the museum to mark the 77th anniversary of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident. On 3 September 2020, amid the Covid-19 pandemic, the seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee of the CCP, presided over by Xi, attended a slightly subdued yet widely publicized event at the museum to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the victory of the war.Footnote 49 Despite its prime importance in China's Second World War memoryscape, the museum has gained relatively little scholarly attention – far less than the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall – and the few analyses that do exist are of earlier versions of the main exhibition.Footnote 50

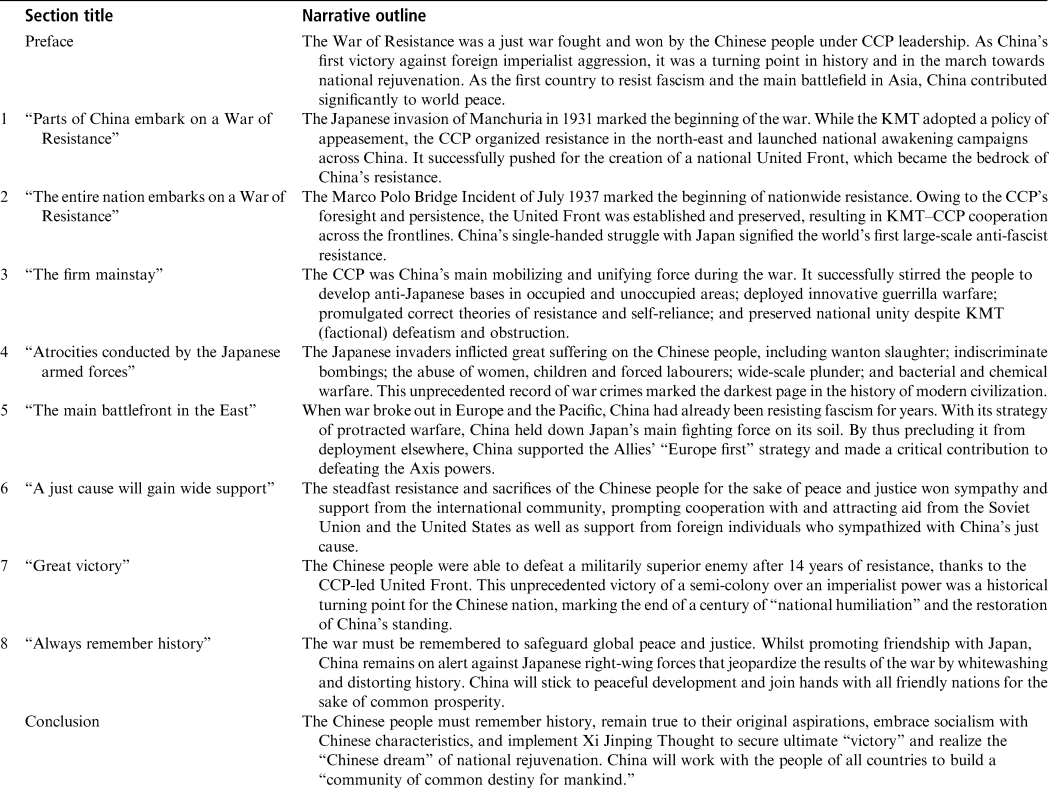

The permanent exhibition's current incarnation, entitled “Great victory, historical contribution” (Weida shengli, lishi gongxian 伟大胜利,历史贡献), was launched in August 2015 to mark the 70th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. The phrase “great victory” first emerged in the exhibition title during a major renovation in 2005. This signalled the beginning of a gradual shift from an emphasis on victimhood towards a more empowering retelling of China's war experience, although the focus in the 2005 exhibition was still on Japanese atrocities and Chinese suffering.Footnote 51 This changed following the 2015 makeover of the exhibition, with the new narrative, outlined in Table 1, having been updated and revised to align with Xi Jinping's new, more triumphalist reading of the history of the Second World War.

Table 1: Narrative Outline of the Permanent Exhibition in China's War of Resistance Museum

In presenting this China-centred account emphasizing national unity, CCP steadfastness and inevitable victory, the narrative resembles that of the latest edition of the eighth-grade history textbook, discussed above. Japanese atrocities and Chinese victimhood do feature in the narrative, but they are once again confined to a single dark chapter in an otherwise upbeat narrative underscoring the agency of the Chinese people in achieving victory. Despite noting the KMT's moral failures and downplaying its diplomatic successes, the narrative is inclusive in that it acknowledges that the KMT played some positive role in cooperating with the CCP towards China's anti-fascist resistance. A notable difference from the textbook is that the exhibition narrative echoes Xi's speeches in placing a strong emphasis on the contemporary significance of history's “lessons.” The Chinese people, whether at home or overseas, are told that they should unite under CCP leadership so they can realize their “Chinese dream.” The international community, for its part, should acknowledge China's historic contribution to victory and justice and embrace Chinese notions of global governance to safeguard global peace.

Formal diplomacy: commemoration initiatives at the United Nations

Xi Jinping has repeatedly stressed the critical importance of the central CCP leadership at the highest level to the success of China's national strategies. A major institutional reform to strengthen and unify Party control over China's foreign policy was the establishment in 2018 of the Central Foreign Affairs Commission (CFAC).Footnote 52 Organized directly under the Politburo and chaired by Xi personally, the CFAC serves as the central institution in charge of coordinating China's foreign policy between the Party, government and armed forces. Other manifestations of increased centralization of foreign policy under Xi are the elevation of Yang Jiechi 杨洁篪, China's foremost diplomat and CFAC director, to the Politburo of the CCP and the appointment of the incumbent foreign minister, Wang Yi 王毅, as state councillor. On the one hand, these changes have helped the CCP to introduce major new policies, including China's first neighbourhood policy and the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013, and new Chinese governance concepts, such as “major-power diplomacy” and “community of common destiny for mankind.” On the other hand, China has also become an outspoken supporter of the existing global system under the United Nations (UN). According to Rosemary Foot, the UN is Beijing's multilateral venue of choice, because it accords China considerable status as a great power and global stakeholder, and the UN's foundational principles of sovereignty and legal equality closely match Chinese preferences.Footnote 53

In 2015, taking its turn as president of the UN Security Council (UNSC), China initiated an “open debate” with the theme “Maintenance of international peace and security: reflect on history, reaffirm the strong commitment to the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations.” In an advance note, Beijing expressed its hope that the debate would encourage member states to “reaffirm their commitment” to the principles of the UN Charter and create a “suitable atmosphere” for the commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the victory in the war against fascism and the founding of the UN.Footnote 54 Urging member states to reflect deeply on history, China called on these states to uphold “the principles of sovereign equality and non-interference in internal affairs,” commit to the “peaceful settlement of international disputes,” “uphold democracy and the rule of law in international relations,” and “pursue common development and win-win cooperation.” By observing that the UN was “born out of the ashes of the Second World War,” the note established a clear and direct link between the history of the war and Beijing's current visions of global governance.

Foreign Minister Wang Yi elaborated on these themes during the debate on 23 February 2015.Footnote 55 Perhaps even more significant was Xi Jinping's keynote address before the UN General Assembly in September of that year.Footnote 56 Reflecting on the history of the war, he drew attention to two points. First, as the main battlefront in the East during the Second World War, China made a historic contribution to the global war against fascism by not only rescuing the Chinese nation from Japanese aggression but thereby also aiding the European and Pacific war efforts. Second, as a result of this great contribution to peace, China was a principal founder of the UN, being “the first country to put its signature on the UN Charter.”Footnote 57 Indeed, the Nationalist diplomat Gu Weijun 顾维钧 (Wellington Koo) had been the first to sign the Charter on 26 June 1945, followed shortly thereafter by the CCP delegate, Dong Biwu 董必武. Photos of this historic event are displayed prominently in the War of Resistance Museum and in the National Museum in Beijing, and Xi and other Chinese officials have recalled the occasion in several important speeches.Footnote 58 At the 56th Munich Security Conference in February 2020, for example, Wang Yi noted that “as the first founding member of the UN to sign its Charter, China has stayed true to the UN's founding aspirations and firmly defended the purposes of the Charter and international law.”Footnote 59

On the significance of history for the present and future, the Chinese leaders made two further two points. First, all member states should follow China's example of reaffirming their commitment to world peace and the founding principles of the UN. Second, to translate these principles into practice, member states should work together in building a “new type” of international relations featuring win-win cooperation and creating a “community of common destiny for mankind.”Footnote 60 Thus, under Xi, history's “lessons” for the international community are framed in a forward-looking, moderate and generally constructive way; they do not emphasize historical wrongdoings or resentments, nor do they exclude any international actors from Chinese visions of global order. Presenting China as a principal founder and stakeholder of the post-war global order undergirds not only Beijing's diplomatic efforts to preserve the basic UN system but also its inherent right to propose reforms to that system. Following the increase of tensions with the United States in recent years, recalling the war's legacy in moral terms around dichotomies of peace versus aggression and harmony versus hegemony also allows the CCP to portray “hegemonic” global forces – mainly the United States – as disrupters of the UN-based multilateral order and hence as a “threat” to global peace.Footnote 61 With Beijing's quest for “national greatness” being highly contingent upon regional stability and peace, this veiled warning is a reminder of how closely intertwined the domestic and international narratives are.

A Paradigm Shift: Recounting Greatness

The three cases analysed in this article bear testimony to the carefully planned and widely implemented decision of the central CCP leadership to reshape the basic interpretative paradigm of China's War of Resistance against Japan. The result is a highly unifying, empowering and aspirational representation of “national greatness” that remixes select elements of the previous two paradigms. In emphasizing China's “great victory,” the new narrative departs from the dominant trope of the Deng/Jiang years, which was to portray China as a weak and passive victim of Japanese atrocities. At the same time, it differs from the earlier discourse under Mao by vesting primary agency in the united Chinese people rather than the revolutionary vanguard, and by framing the war around a moral (rather than Marxist-Leninist ideological) dichotomy of justice defeating evil.Footnote 62 By highlighting the wartime cooperation between the CCP and the KMT, so studiously ignored during the Maoist era but gradually revived since, the narrative seeks to involve the entire “Chinese people” – including the Chinese diaspora and the Taiwanese – into a single, pan-Chinese nationalist discourse. Instead of framing CCP–KMT relations in zero-sum terms or comparing their respective quantitative contributions to the war, Xi offers a qualitative assessment of their joint effort in which the CCP's success in achieving and maintaining national unity prevails as the decisive factor in China's ultimate victory.

The Chinese people's “victory” and “greatness” have thus become the central tenets of official Second World War remembrance in China, following a shift initiated under Hu and completed under Xi. Victimization and victory narratives were still competing for dominance in Hu-era speeches, textbooks and exhibitions; now, the emphasis is squarely on victory. This is not to suggest that victimization has lost its significance as a theme in the Chinese discourse on the war. On the contrary, just as the “revolutionary heroism” retained its relevance even after it was replaced as the main paradigm in the 1980s, so does its successor narrative remain a powerful trope in the public sphere today, as reflected both in the official remembrance of the Nanjing Massacre and in popular initiatives.Footnote 63 The cases studied here make it very clear, however, that the victimhood theme is no longer central to the CCP's main message. In the newest textbooks and exhibitions, Chinese victimhood is confined to a single (if dreadful) chapter in an otherwise upbeat and inspiring narrative, while Chinese leaders have stopped mentioning wartime atrocities and suffering in their speeches. Museum exhibitions outside of China's wartime occupied areas, such as in the former Nationalist capital of Chongqing, pay virtually no attention to the Nanjing Massacre.Footnote 64 A strong focus on resistance and heroism, not victimhood, also characterizes exhibitions at “Red” heritage sites across the country and at the National Museum in Beijing.Footnote 65 Even at the Memorial Hall of the Victims of the Nanjing Massacre, the once almost exclusive focus on victimhood has been counterpoised by the 2015 addition of a major exhibition hall commemorating China's victory in the war.Footnote 66 A similar trend can be observed in the once ubiquitous anti-Japanese rhetoric. Although Japan's past crimes and present right-wing inclinations remain sensitive and potentially inflammatory topics in China and the object of important historical “lessons,” Japan's former role as the evil “other” has been minimized in museum narratives and removed altogether from school textbooks and official speeches.

As essentializing and unifying as the new central narrative is, it does feature slight variations in agency and emphasis depending on the audience primarily targeted. Two basic audiences can be distinguished. First and foremost is the “home” audience, the “Chinese people,” which from Beijing's perspective includes both mainland Chinese and their overseas brethren in Taiwan and elsewhere in the world. This audience is targeted mainly through the school curriculum and museum exhibitions, as analysed in this article, as well as through public commemorations and Chinese-language (social) media. The focus of these narratives is on the Chinese people and their great victory, but with a strong emphasis on the CCP as the indispensable force. The apparent goal is to legitimize and strengthen the Party's rule by using the people's war as a rallying point for pan-Chinese patriotism, unity and solidarity. “Red” history alone, as Beijing knows very well, could not provide a similarly inspiring and mobilizing force, because the divisive and traumatic legacies of China's revolution are alienating to not only most Taiwanese but also to many mainland Chinese who suffered during the turbulence of post-war China. The purpose of remembering the war is to deliver a message to the Chinese people that China cannot survive, let alone regain strength, without the CCP. A remarkable implication of using Second World War history for this purpose is that the “great victory” of 1945 has come to rival the revolution of 1949 as the central foundational event of modern China.

The other major target is the “external” audience, which comprises the international community and particularly those major powers that shape regional and global politics. This global audience is targeted primarily through diplomacy at major multilateral forums, such as the UN, but also at institutions like BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization as well as through public commemorations, war exhibitions and the media.Footnote 67 In these representations, the primary agent is again the Chinese nation, but with a more statist focus emphasizing China's contribution to global peace and justice. The main purpose of remembering the war in the international context is to promote an image of the PRC as a peace-loving and responsible power, which has always stood on the “right” side of history as a “maker,” and certainly not a “breaker,” of the post-war international order and the values underpinning it. Claiming (co-)ownership of the UN system allows Beijing to advocate a return to the primacy of sovereignty and non-interference. This conservative “historicism” thus does not mean that China advocates the status quo: implied within it is an assertion of Beijing's right to propose reforms and to resolve its “unfinished business” in the East China Sea and Taiwan.

The pivot away from both the crude revolutionary rhetoric of the Maoist era and the resentful victimhood narratives of the Deng/Jiang years could be taken as a continuation of the trend towards the “normalization” and “globalization” of war historiography identified by Rana Mitter in 2010.Footnote 68 There are, however, two important reservations to this, suggesting that war memory in China cannot be easily placed on the same footing with war memory in other countries. First, the official Chinese narrative has become more, rather than less, exclusively Sino-centric under Xi, and hence anything but “globalized.” In 2005, Hu Jintao spoke generously of the “solidarity” of the “anti-Fascist allies worldwide,” but for Xi the war was won by the Chinese people, initially fighting alone and later “aided” by some “foreign governments and friends.” Second, in line with the general trend of increased censorship and control under Xi, public war commemoration has been placed much more firmly under the central aegis of the CCP, leaving the public and scholars alike minimal room to deviate from what it deems to be the “correct view of history.”Footnote 69

With domestic and foreign challenges mounting now that China's “great rejuvenation” has entered its “critical stage,” the CCP has observed that the stakes are high and the risk of failure is great.Footnote 70 At what the Party regards as a vital hour in its history, it appears eager for the Chinese people to close ranks under its leadership and for the international community to accept China as a responsible yet equal partner.Footnote 71 In a speech marking the 75th anniversary of V-J Day, Xi emphasized that “the nation's great spirit” of patriotism and heroism, which had led the Chinese people to victory in the Second World War, “is invaluable today and can motivate the Chinese people to overcome all difficulties and obstacles and strive to achieve national rejuvenation.”Footnote 72 The new paradigm of the war's commemoration was designed specifically to serve these goals. Aspirational, empowering and seemingly “normalized,” it is premised on recounting China's national greatness in the past so as to establish and secure that greatness in the present and future. Under the new paradigm, China's discursive “other” is neither the Chinese people's erstwhile “class enemy” nor the “Japanese rightist” as such, but any external force that seeks to thwart China's claim to greatness and “ultimate victory.”Footnote 73 Similarly, any Chinese national who willingly aids such subversive efforts risks being branded a traitor (hanjian 汉奸) and compared to Wang Jingwei, China's despised “Quisling.”Footnote 74

Conclusion

The Chinese people have stood up under Mao, grown rich under Deng and are becoming strong under Xi. This is how China's paramount leader summed up seven decades of revolutionary history in his landmark “new era” speech of October 2017.Footnote 75 A new era calls for a new discourse, one befitting current goals and ambitions, and this is precisely where Xi's recasting of Second World War memory fits in. Compared with the preceding paradigms of “revolutionary heroism” and “national victimhood,” the new line is respectively more inclusive and empowering. It is also more tailored for international use, holding clear lessons – and implicit warnings – for the present and future. A key question will be how this more self-assertive and aspirational new discourse will hold up in the face of the mounting global pressures on China and the CCP.

This study has sought to contribute to the literature on war remembrance in China by laying out a fundamental, yet largely overlooked, shift in Chinese official discourse. The focused review of new representations in the school curriculum, museum exhibitions and formal diplomacy has begun to establish the scope and depth of this shift and to identify the substantive themes, actors, dichotomies and “lessons” that are central to the new narrative. Further research is needed to explore how this shift is manifesting in domains where the central leadership exercises less direct control, such as in localities outside of Beijing, social media and historiographical scholarship.

Acknowledgements

This study is a product of a collaborative project between the Chongqing Research Center for the Great Rear Area of the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression at Southwest University (China) and the LeidenAsiaCentre at Leiden University (The Netherlands). I thank the LeidenAsiaCentre for initiating and advancing the project and the History College of Southwest University, where I completed a significant part of the field research, for its support and for hosting a joint conference on Second World War commemoration in September 2019. I am indebted to the conference participants and the two anonymous reviewers of The China Quarterly for their valuable suggestions and comments.

Biographical note

Dr Vincent K. L. CHANG is a lawyer and a historian of modern China. He holds concurrent positions at Leiden University and the LeidenAsiaCentre, The Netherlands, having previously worked at the History College of Southwest University, China. His research interests include the Second World War and the post-war period, historical memory, and China's historical and contemporary international relations.