A large literature based on direct question surveys finds that around 90 per cent of Chinese citizens support the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).Footnote 1 One such survey, by the Ash Center for Democratic Governance at Harvard University, routinely appears in CCP propaganda.Footnote 2 From this, scholars conclude that the CCP enjoys genuine legitimacy, presumably from its ability to foster economic growth, provide public goods and persuade citizens of policy successes.Footnote 3 These conclusions assume that Chinese citizens, as Daniela Stockmann, Ashley Esarey and Jie Zhang write, do not misrepresent their opinions “in surveys out of political fear.”Footnote 4

Is this true? Do Chinese citizens answer direct question political surveys honestly? Does the CCP enjoy overwhelming support? There are, we believe, reasons for scepticism. To explain the rapid decline of the Soviet Union, Timur Kuran coined the term “preference falsification,” which describes the tendency for citizens in autocracies to conceal political opinions owing to the threat of repression.Footnote 5 In one recent meta-analysis encompassing 21 studies, Graeme Blair, Alexander Coppock and Margaret Moor conclude that respondents “overreport support for authoritarian regimes” by 14 percentage points and “underreport opposition.”Footnote 6 This suggests that preference falsification is endemic in autocracies. China is unlikely to be an exception.

In this paper, we show that preference falsification in China is widespread. We report the results of two survey experiments that used quota sampling to balance the sample on the most recent census. We asked respondents direct questions about their support for the CCP and their willingness to protest against it. The results were consistent with conventional wisdom. More than 90 per cent of respondents reported satisfaction with the CCP and just 8 per cent suggested that fear of state repression discouraged them from protesting. We then asked these questions as list experiments, which let respondents express sensitive opinions without stating them directly. On average, our list experiments suggest that respondents overstate regime support in direct questioning by 28.5 percentage points. Roughly 40 per cent of citizens decline to protest owing to fear of repression, quadruple the rate under direct questioning. This preference falsification rate is double the 14 percentage point average found by Blair, Coppock and Moor and nearly three times greater than that found by Timothy Frye and colleagues in Vladimir Putin's Russia.Footnote 7 Our list experiments estimate support for the CCP at between 50 per cent and 70 per cent. This, we emphasize, is an upper bound, since our results also suggest the possibility that list experiments may not fully mitigate preference falsification due to residual concerns about online surveillance. We find no evidence that the wealthy, educated and urban are the CCP's primary detractors, as existing literature suggests.Footnote 8 Rather, opposition is more widespread. This degree of preference falsification, as we argue below, suggests scholars should be cautious when measuring support for repressive governments using other survey methods, like Single-Target Implicit Association Tests (ST-IATs) and affect transfer studies, which provide less anonymity in an environment of online surveillance.

We build on three recent papers that use list experiments to measure CCP support. Wenfang Tang embedded list experiments in the World Values Survey in China and found no preference falsification.Footnote 9 However, anonymity in this survey was reduced by floor and ceiling effects and the verifiability of the experiment items (for example, “I attend a sports match once a week” rather than “I consider myself a sports fan”) More generally, in-person survey enumerators have reported that respondents sometimes count list items on their fingers, which further reduces anonymity. Darrel Robinson and Marcus Tannenberg found evidence of preference falsification but used an online respondent pool that skewed younger, affluent, educated and urban.Footnote 10 This demographic is widely regarded as the one most opposed to the CCP,Footnote 11 and so it is unclear whether this rate of preference falsification is representative of China's broader population. Stephen Nicholson and Haifeng Huang used a list experiment to measure trust in local and central governments, and found a preference falsification rate of between 5 and 14 percentage points, which is consistent with Blair, Coppock and Moor's meta-analysis.Footnote 12 We focus on support for the CCP more specifically, using questions that let us compare rates of preference falsification in China, Russia and elsewhere. We believe that documenting and explaining variation in preference falsification across autocracies is a crucial direction for future research, especially given recent claims that autocratic governments often enjoy genuine support.Footnote 13

Design

Survey respondents sometimes misrepresent their true opinions out of concern for how they will be perceived by enumerators or monitors. This is known as sensitivity bias, social desirability bias or preference falsification. Scholars have identified several techniques to circumvent it. Among the most popular is the list experiment, which lets respondents express sensitive opinions indirectly. List experiments randomize respondents into treatment and control groups. Respondents in the control group receive a list of three non-sensitive statements and are asked how many they agree with. Respondents in the treatment group receive a list of the same three non-sensitive statements plus one sensitive statement and are also asked how many they agree with. Since the treatment group receives one more statement – the sensitive statement – than the control group, the difference in means between the groups represents the share of respondents who agree with the sensitive statement. Because they confer a sense of anonymity, list experiments have been used to measure racism in the American South and other sensitive behaviour.Footnote 14

More recently, scholars have used list experiments to measure support for autocratic governments. In Russia, Frye and colleagues estimated support for Vladimir Putin at roughly 80 per cent, similar to the 87 per cent implied by direct questioning and yielding a preference falsification rate of just 7 percentage points.Footnote 15 As discussed above, there is widespread disagreement about whether Chinese citizens conceal opposition to the CCP. We aim to resolve this question using techniques comparable to those used by Frye and colleagues in Russia.Footnote 16 We partnered with a private market research firm to field two surveys in June and November 2020. These waves were not longitudinal and recruited different respondents; the intent of fielding two waves was to ensure the robustness of our findings. We used quota sampling to balance the sample on the 2010 census on age, gender, income and province. The survey was administered via the internet. Each wave recruited approximately 2,000 respondents. We began by asking respondents demographic questions such as age, gender, ethnicity, educational attainment and income, among others.

Next, we asked respondents direct questions about their support for the CCP. For comparison, several questions were drawn or adapted from previous surveys in China and Russia.Footnote 17 These questions appear in Table 1. The first three questions focus on regime support and vary in how directly they implicate the CCP. The first and most implicating prompt is: “I support Comrade Xi Jinping's 习近平 leadership.” Next, we examined whether the government was “working for the people” and “responsive to their needs.” The least implicating prompt focuses on China's “system of government.” For each, respondents were asked whether they “strongly agree,” “agree,” “somewhat agree,” “neither agree nor disagree,” “somewhat disagree,” “disagree” or “strongly disagree.” Then, we asked respondents whether they “would be willing to protest or participate in a collective walk against the government,” a common euphemism for protest. Since the decision not to protest may be motivated by either fear of government repression or satisfaction with government policies, respondents who indicated that they would not protestFootnote 18 were then presented with an additional question designed to identify the mechanism: whether they refrained from protest because they were “afraid of the consequences” or “supported the government's policies.”

Table 1. Direct Question Prompts

Finally, we asked respondents the same questions as list experiments.Footnote 19 We randomized respondents into treatment and control groups. For each list experiment, the control group received three non-sensitive statements. The treatment group received the same three non-sensitive statements plus one sensitive statement corresponding to a direct question prompt. Again, respondents were asked how many statements they agreed with, not which statements they agreed with, thus letting respondents express sensitive opinions indirectly. All sensitive and non-sensitive list experiment items appear in the online Appendix.Footnote 20 To foster anonymity, we made the non-sensitive items as non-verifiable as possible. To avoid ceiling and floor effects – which occur when respondents agree with all items or none, respectively – we chose non-sensitive items that are likely to be negatively correlated. We focus our attention on respondents who completed the survey in between the 10th percentile (5 minutes) and the 90th percentile of completion times (25 minutes), a range we found to be reasonable in pilots.

The online Appendix includes other information about the experiment: a discussion of research ethics, balance statistics, design considerations and robustness checks. We also show that the results are substantively unchanged when excluding respondents who engaged in “satisficing” behaviour: a measure of inattentiveness in the context of list experiments.

Results: Direct Questioning

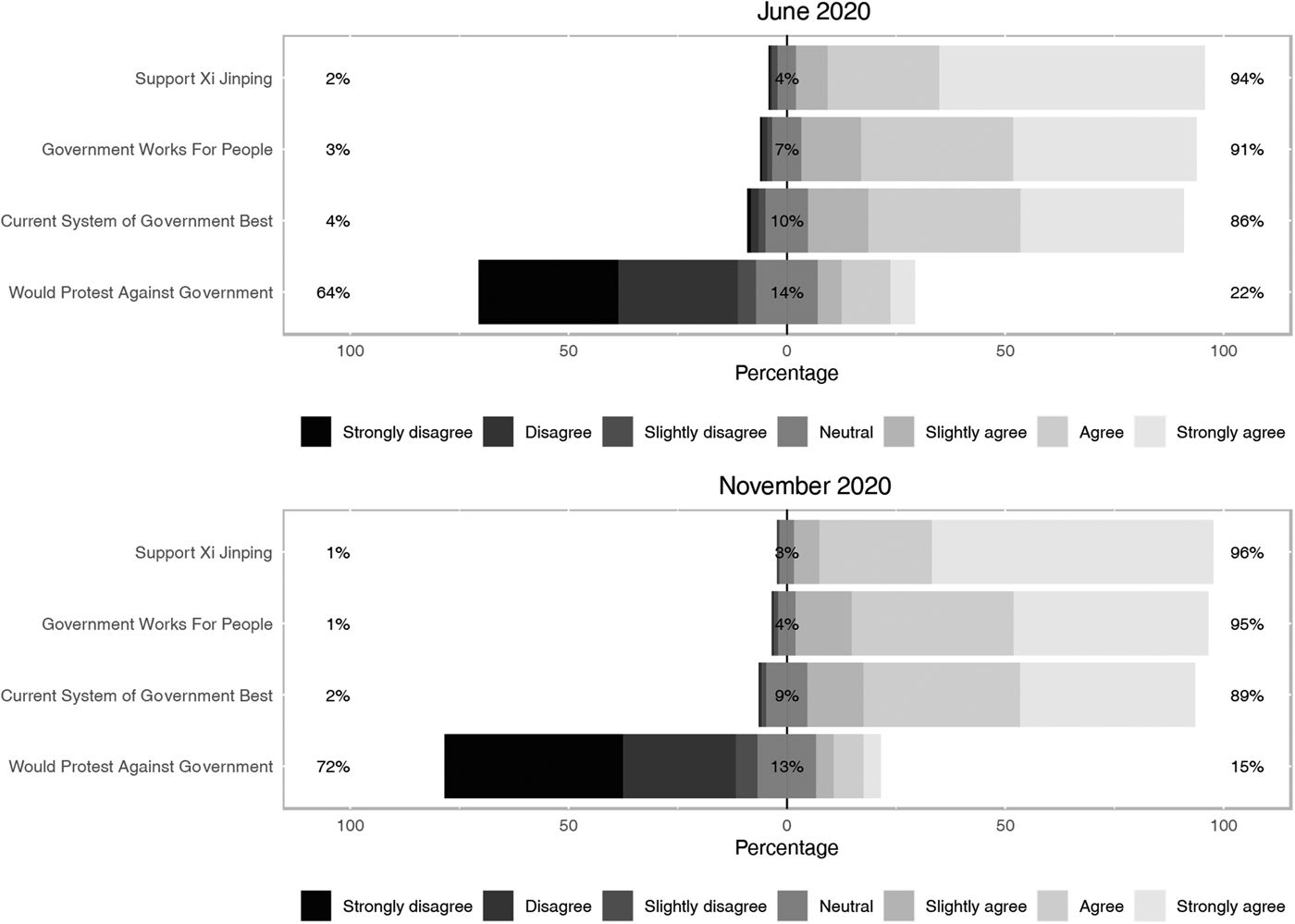

Figure 1 presents the direct question results. The top panel focuses on June 2020 and the bottom panel on November 2020. Consistent with existing direct question surveys, we find overwhelming support for the CCP. In June, 94 per cent of respondents supported Xi Jinping, 91 per cent of respondents believed the government worked for the people, and 86 per cent of respondents believed China's current system of government is best. For all three questions, “strong support” for the regime was the modal response. Only 22 per cent of respondents said they were willing to protest against the government, compared to 64 per cent who would not. Of those 64 per cent, we show in the online Appendix, 92 per cent would not protest because they supported regime policies, while just 8 per cent would not protest because they feared repression. From the bottom panel, the results from November were virtually identical. If these results are true, citizens support the CCP and do not fear repression.

Figure 1. Direct Question Results

In the online Appendix, we use OLS regression to probe whether expressed support for the CCP varies according to a respondent's demographic characteristics: income, education, ethnicity, age, gender, CCP membership and the urbanization level of the county in which they reside as measured by night lights. We find no differences in expressed support across income, education, age, gender, CCP membership and urbanization. The only consistent correlate is ethnicity. Relative to minorities, Han respondents are less likely to say they support Xi Jinping, believe the current system of government is best, and would not protest because they fear repression. This may seem surprising. The Han majority is subject to less repression than China's ethnic minorities and enjoys preferential government policies.Footnote 21 In our view, this suggests China's ethnic minorities may engage in more preference falsification than the Han majority, something we test in the next section.

Results: List Experiments

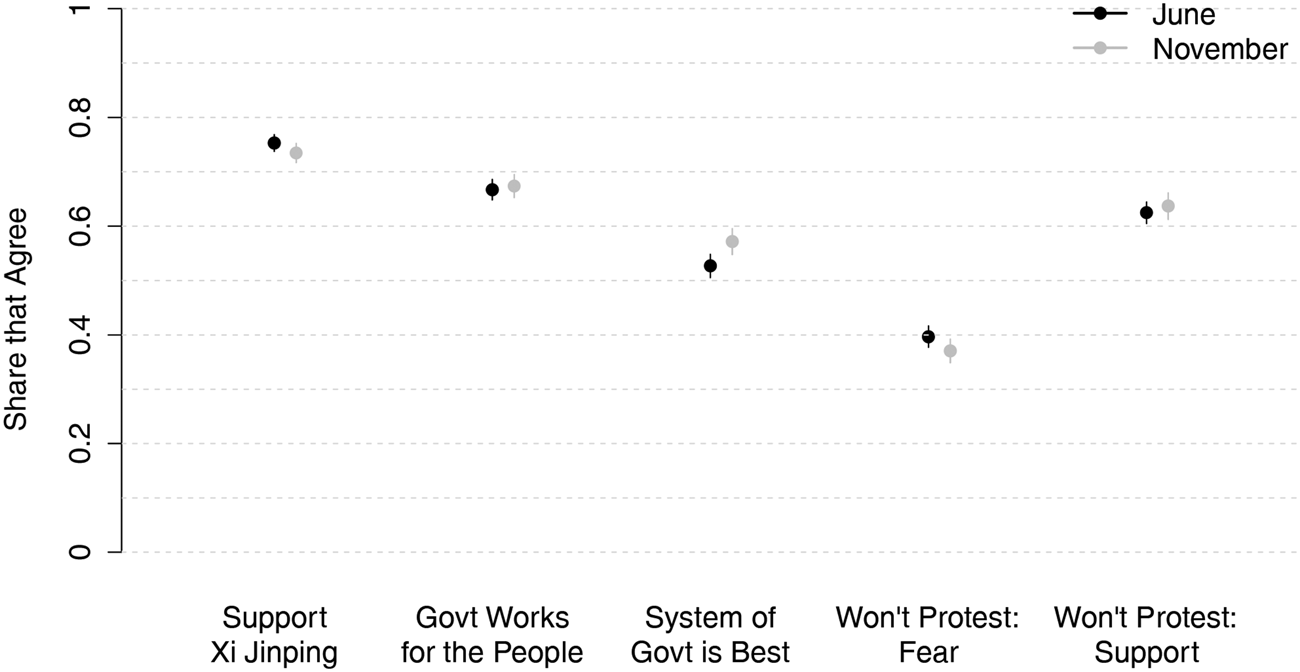

The list experiment results in Figure 2 reveal widespread preference falsification and a different view of CCP rule. Each statement on the x-axis corresponds to one of the regime support prompts from Table 1, now asked in the form of a list experiment. The y-axis gives the share of respondents who agree with each prompt, along with 95 per cent confidence intervals.Footnote 22 Letting respondents express opposition to Xi Jinping indirectly reduces his support by nearly 30 percentage points, from around 95 per cent to between 65 and 70 per cent. Regime support declines further with questions that implicate the leadership less directly, which suggests the possibility that list experiments may not fully mitigate incentives for preference falsification. Roughly 65 per cent of respondents agree that the government works for the people and is responsive, down from between 90 per cent and 94 per cent. Just over 50 per cent of respondents agree that China's system of government is best, down from between 85 per cent and 89 per cent. Nearly 40 per cent of respondents say they would not join an anti-regime protest because they fear repression, up from 8 per cent. Given the possibility of residual concerns about online surveillance, these estimates constitute the upper bounds of CCP support. Still, they suggest a preference falsification rate that is nearly three times greater than that documented by Frye and colleagues in Putin's Russia.

Figure 2. List Experiment Results

In the online Appendix, we probe whether these list experiment estimates vary according to demographic characteristics.Footnote 23 Across questions and survey waves, regime support varies consistently only across three characteristics: ethnicity, CCP membership and education, which are all associated with more support for the regime. First, ethnic Han support Xi Jinping about 20 percentage points more than minority respondents. In June, Han respondents were about 15 percentage points more likely to believe the government works for the people. In November, they were about 20 percentage points more likely to believe China's system of government is best and to refrain from protesting because of their support for government policies. This suggests the direct question result – Han citizens appear less supportive of the CCP – is driven by minorities’ fear of repression under direct questioning, consistent with the CCP's widespread ethnic repression.Footnote 24 Second, college-educated respondents are between 10 and 20 percentage points more supportive of the CCP than respondents who completed early middle school, although only three of five indicators are significant in the November survey. This may suggest the CCP's efforts to reshape educational curricula have succeeded.Footnote 25 Alternatively, this may reflect a job market that has long favoured college-educated Han.Footnote 26 Finally, CCP members are about 10 percentage points more supportive of the regime. This makes sense, since they elected to join the Party and benefit from its rents. Other demographic correlates are not consistently associated with regime support. We include a range of robustness checks in the online Appendix.

The Urban Elite and Opposition to the CCP

Scholars generally regard the urban elite as the CCP's primary potential challengers, partly because they have led anti-regime protests in the past.Footnote 27 Reflecting this, using an online, direct question survey, Jennifer Pan and Yiqing Xu find that support for political and economic liberalization is correlated and more common among the wealthy, educated and urban.Footnote 28 However, the CCP has long sought the support of this group through urban bias policies that provide preferential access to jobs, credit and social welfare benefits.Footnote 29 Perhaps reflecting these countervailing forces, we find that none of these factors conditions CCP support in direct questioning. In list experiments, the educated are slightly more supportive of the CCP, not less. Our results suggest that the CCP's efforts to co-opt urbanites may have been successful, yielding levels of discontent that are now similar across urban and rural areas. While outside the scope of this paper, the tendency of protest movements to emerge in urban areas may be more a function of the coordination advantages afforded by urban life than heterogeneity in support for the CCP across rural and urban areas.

Implications for Other Survey Methods

Although we employed list experiments to facilitate comparison with Frye and colleagues’ results in Russia, scholars have employed other methods to divine sensitive opinions. Perhaps the most important is the Single-Target Implicit Association Test (ST-IAT), which psychologists use to differentiate a respondent's implicit and explicit views. Implicit views are instinctive and formed prior to cognition, while explicit views are more deliberate. ST-IATs ask respondents to group a term of interest like “female” with affect words like “good” or “bad.” Respondents’ explicit beliefs are measured by the words they link with “female,” while implicit beliefs are measured by how quickly they do so. Psychologists have used ST-IATs to measure implicit attitudes about sexism and racism.Footnote 30 More recently, ST-IATs have been used to distinguish between implicit and explicit trust in government, in both democraciesFootnote 31 and autocracies.Footnote 32

This is an exciting research agenda, since it may provide an opportunity to measure the long-term effects of propaganda and censorship. For two reasons, however, our results suggest scholars of autocracy should approach ST-IATs with caution. First, ST-IATs, which are typically administered on a computer, do not confer anonymity if respondents are concerned about online surveillance. Respondents may feel pressure to associate “government” with positive terms. Second, in quickly linking “government” with positive terms, respondents may reveal that they have internalized the threat of repression, not support for the government. Lauren Young shows that inducing even a mild state of fear reduces an individual's willingness to engage in dissent. These “defensive instincts,” as one of Young's informants calls them,Footnote 33 may lead respondents to quickly group “government” with the regime-preferred affect term. The same considerations apply to affect transfer studies and item non-response rates.Footnote 34 As long as survey methods do not confer anonymity and respondents know the government's preferred response, preference falsification is a concern.Footnote 35

Conclusion

Scholars routinely measure support for the CCP via direct question surveys, the results of which suggest approval ratings above 90 per cent. From this, scholars conclude that the CCP enjoys real legitimacy, its policies are widely supported and its propaganda and censorship operations are persuasive. This research agenda assumes that Chinese citizens do not misrepresent political opinions due to fear, contrary to evidence of preference falsification in other autocracies.Footnote 36

This assumption – that Chinese citizens do not misrepresent political opinions in surveys due to fear – is wrong. Using two survey experiments and a sample balanced on the most recent census, we show that respondents overstate CCP support in direct questioning, on average, by 25.5 percentage points, double the 14 percentage point average in autocracies found by Blair, Coppock and Moor, and nearly three times greater than Frye and colleagues find in Russia. Our list experiments put support for the CCP at between 50 per cent and 70 per cent. This, we caution, is an upper bound, since list experiments may not fully mitigate preference falsification owing to residual concerns about online surveillance. We show that fear of government repression keeps some 40 per cent of Chinese citizens off the streets. We find no evidence that the wealthy, educated and urban are the CCP's primary detractors. To the contrary, opposition is more uniform. While these results suggest some support for the CCP, they are far from the overwhelming support that constitutes the conventional wisdom.

We suggest two directions for future research. First, scholars should stop using direct question surveys to measure public opinion in China and other repressive environments and reassess empirical work that assumes preference falsification does not exist. Second, scholars should treat variation in preference falsification rates across autocracies as worthy of documenting and explaining. Doing so suggests novel questions about autocratic politics. Is less preference falsification correlated with more protest? Does the rate of preference falsification provide information about a regime's repressive capacity or the likelihood of democratization by sudden revolution?

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741023001819 (also at https://erinbaggottcarter.com and https://www.brettlogancarter.org).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Center for International Studies at the University of Southern California and the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for financial support.

Competing interests

None. The survey experiments in this paper were granted “exempt” status by the University of Southern California IRB.

Erin Baggott CARTER is an assistant professor in the department of political science and international relations at the University of Southern California and a Hoover Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. She focuses on Chinese politics, propaganda and foreign policy. Her first book, Propaganda in Autocracies, was published by Cambridge University Press in 2023. Her other work has appeared in British Journal of Political Science, Journal of Conflict Resolution, Security Studies, International Interactions and Foreign Affairs.

Brett L. CARTER is an assistant professor in the department of political science and international relations at the University of Southern California and a Hoover Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. His research and teaching focus on politics in the world's autocracies. His first book, Propaganda in Autocracies, was published by Cambridge University Press in 2023. His other work has appeared in Journal of Politics, British Journal of Political Science, Journal of Conflict Resolution, Journal of Democracy, Security Studies and Foreign Affairs, among other outlets.

Stephen SCHICK is a PhD student in the department of political science and international relations at the University of Southern California. His research interests centre on authoritarian political economy and the dynamics of responsiveness and participation under autocracy. His dissertation research will focus on the effectiveness of policy advocacy by firms, think tanks and other organizations in China.