It started with a chance discovery at a second-hand book store – and ended with an appearance on the BBC's Newshour and a New York Times feature. When my PhD student, Tricia Kehoe, came across a dusty old copy of Sue in Tibet, an obscure fictional tale of the adventures of an American missionary's daughter in the Tibetan borderlands in the 1920s, she posted a picture of the book on Twitter. Within minutes she had received a message from Samanthi Dissanayake, Asia editor for the BBC News website. The two swapped emails and discussed the possibility of a piece based on the book. Over the next few weeks, Tricia delved into the author's background, finding missionary documents about the historical family online, and connecting (via Twitter) with a museum in the US that houses the artefacts the family collected while in Tibet. Through the museum, she tracked down the author's family and uncovered the fascinating real life adventures of Dorris Shelton Still which the book dramatizes. The BBC published the resulting piece on their website, which quickly generated a buzz in the Twittersphere. A few hours after the piece was released, Dhruti Shah, a journalist at the BBC World Service, contacted Tricia via Twitter to request an interview, and an hour later she was on air talking to Newshour host James Coomarasamy. The New York Times subsequently featured the story as part of their “Women in the World” series. Count this as another victory for “the engine of creativity that is Twitter,” tweeted Dissanayake. For Tricia, this was a positive outcome. It helped to expand her public profile, generated media exposure for her research and demonstrated a capacity to engage audiences beyond the academy. In an intensely competitive academic job market, it is useful for young scholars to signal such attributes to potential employers, alongside traditional markers of academic excellence. The purpose of this research note is to explore, in a more systematic manner, whether Twitter is a useful tool for China scholars, particularly junior colleagues, and for the China studies field more generally.

External Engagement and Technology

External engagement and the dissemination of research beyond specialist academic outlets have increased in relevance in higher education (HE) in the UK since “research impact” was codified in the 2014 Research Excellence Framework (REF), which determined public funding for research at UK universities. In Australia, the government has similarly pledged to incorporate quantitative and qualitative measures of “impact and engagement” from the 2017 round of the Excellence in Research for Australia exercise. While less systematically applied across the sector, many public funders and university administrators in North America and Europe encourage academics to work with policymakers and the media, and to conduct outreach activities to the broader public. In the context of budget cuts and political will for ensuring “accountability” and reducing a perceived academic “relevance gap,” “deliverables” in the form of diverse outputs in the public domain are a requirement of public research funding in many Western countries. Further compounded by the globalized competition for student recruitment among universities, external engagement has become an expectation for many academics alongside research, teaching and administration. Thus, for PhD scholars-in-training and Early Career Researchers (ECR) in particular, demonstrating the capacity for external engagement can augment an academic CV in a competitive job market. However, honing the skills needed to work with external stakeholders in business, government and the media is an area of postgraduate and ECR training that has traditionally been overlooked. Consequently, although many China scholars would like to participate in public discourses within their fields of interest, many do not feel comfortable doing so.Footnote 1

Across the sector, integral components of academic life are being challenged and enhanced by technology. Conference and seminar conversations no longer have to wait for the Q&A to begin; they take place continuously via social media backchannels. The latest issues of academic journals can be sent directly to smartphones. A plethora of tools and platforms is available for every stage of the research process. In different ways, Google Scholar, RSS and Pinterest have changed how scholars find research and teaching materials. Mendeley, Academia.edu and ResearchGate have changed how papers are stored and shared. Skype, Dropbox and Google Documents have simplified remote collaboration. Social media tools have been adopted as means of scholarly communications and harnessed by Altmetrics to provide a fuller picture of the scientific and social impact of academic output. Making papers available on “pre-publication” repositories like SSRN, or on personal homepages, can increase the reach of academic work beyond the readership of paywall-bound traditional peer-review journals.Footnote 2 And, unlike Virtual Learning Environments or professional Listserv, which are closed to non-members, social media are transparent and anyone can participate. Increasingly, the question is not whether an academic should use these tools but rather which platforms are the most effective, in which combination and how many can be managed without inundating the user.Footnote 3

Twitter as an Academic Tool

Celebrating its tenth anniversary in March 2016, Twitter has a global user base of around 300 million. Less popular than Facebook for connecting with friends and “me-casting,” Instagram for stalking celebrities, or Snapchat for garrulous teenagers, Twitter has shaken off its dominant earlier image of promoting inane ephemera (although it retains these functions for some users).Footnote 4 Despite initial scepticism, many academics have recognized the utility of Twitter for various professional activities. Studies on academic uses of Twitter have identified benefits for teaching,Footnote 5 increasing academic citations,Footnote 6 and as an alternative measure of research impactFootnote 7 and professional competency.Footnote 8 Academics are using Twitter for describing academic practices, giving and seeking advice, critiquing academic culture, promoting publications and conferences, sharing thoughts on current events, and reflecting on teaching practice.Footnote 9 Although social media ties are famously weak,Footnote 10 the low costs and horizontal informalities of Twitter make it particularly appealing to junior academics who can easily approach their senior counterparts. It can be useful at all stages of research, from collecting materials for preliminary literature reviews to post-publication promotion. As such, social media have a potential role in “building the networks of practice which can underpin the development of learning professionals.”Footnote 11 For one scholar, “deciding to opt out of social media is akin to opting out of email in the 1990s.”Footnote 12 Another has written of the “transformation of scholarly practice” wrought by technological developments.Footnote 13 There is a developing conversation about how academics’ proficiency with digital media should be encouraged and rewarded by institutions,Footnote 14 while “being conversant in these mediums is now an expected component of an academic profile.”Footnote 15

China Studies and Twitter

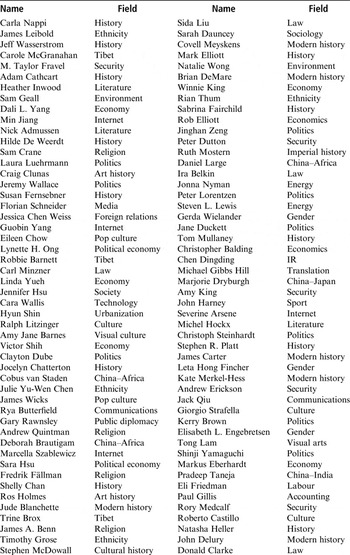

One of Twitter's most obvious attractions for China scholars is that it provides the potential to reach and interact with a substantial range of people with interest and expertise in China from a wide variety of professional and experiential backgrounds.Footnote 16 A diverse selection of relevant actors is active on Twitter, from the Dalai Lama and Ai Weiwei 艾未未 to the People's Daily and Xinhua. Although Twitter is inaccessible behind the Firewall, a substantial cohort of Chinese intellectuals and activists access the platform via VPN software, using it as a space outside of the circumscriptions of the authoritarian information regime that prevails over the Chinese internet.Footnote 17 Yet, while there are users among some Chinese journalists, PRC citizens based overseas and large cohorts based in Hong Kong and Taiwan, Twitter does not provide access to the vast majority of PRC internet users.Footnote 18 What Twitter does offer in abundance is a wide range of Western media covering China and hundreds of China correspondents, NGOs, businesspeople, students, policy analysts, expats, etc. The academic field of China Studies is also well represented on Twitter by numerous journals like The China Quarterly and China Information as well as academic departments and institutes such as Harvard's Fairbank Centre, the China and the World Centre at the Australian National University, and the US–China Centre at the University of Southern California. There are also a significant number of China studies scholars active on Twitter, across all fields and career stages, including many PhD students. Over the last four years, I have been tracking the activities of China scholars on Twitter. The number has grown to more than 300 at time of writing, with a further 200 graduate students. This cohort includes academics working across the globe, in many disciplines focusing on many disparate aspects of China past and present. Table 1 illustrates the diversity of research interests among 75 China scholars on Twitter.Footnote 19 As a proportion of all China scholars, this is not a large number, and greater concentrations of fellow academics are active on professional email lists such as China-pol or Modern Chinese Literature and Culture. However, professional lists and social media are useful in different ways, and they can coexist.

Table 1: China Scholars on Twitter

While using Twitter is straightforward, identifying a strategy for getting the most out of it takes time. Self-presentation and finding an appropriate voice, including balancing individual, professional and employer perspectives, require consideration. Network-building and finding an audience require engagement through sustained and time-consuming activity. Twitter requires users to share messages of 140 characters or less, a constraint that can be intimidating for academics used to discoursing at length on nuanced topics. However, the word limit trains users to express ideas in a very succinct form – a skill that is useful for interactions with the media and “elevator pitches” – and is sufficient to make a concise comment, while more nuanced points can be made over several linked tweets. Users can choose to follow the messages of other people in whom they are interested, and choose to actively engage and inform by sharing thoughts and information, or passively collect material and follow discussions. Using Twitter as a means to receive information is usually quicker and more diverse than academic email lists, and sometimes allows users to “be present” at momentous events like the siege of Wukan 乌坎 and the “umbrella” movement. However, Twitter is noisy, and overzealous or unfocused “Tweets,” pugnacious trolls and various automated messages and advertisements can easily become a distraction. Exercising caution in whom and how many people to follow, judicious use of the “mute” button and refusal to enter online arguments, are lessons well learned. Maximizing Twitter's potential for building recognition for a researcher's specific area of expertise and forging academic and other professional networks requires sustained, active engagement. Providing something useful, especially if people can't necessarily get the same commodity elsewhere, is an effective way of establishing one's value to the China-watching Twittersphere. This can take the form of commentary on contemporary events, insights from research projects, thoughts relating to the research field or profession, or linking to specialist materials. Numerous China scholars, including many of those listed in Table 1, have established a niche area of expertise, marking themselves out as go-to sources for expert commentary on a particular topic.

Twitter is an iterative game and a Twitter network feeds on reciprocity. Sharing news of others’ publications or bon mots establishes goodwill that may be reciprocated later. Sharing information, bringing people into conversations and acknowledging other users’ contributions helps concretize connections. Twitter is informal, and it is easy to communicate with people one might not so easily approach in the physical world. Re-tweeting eminences’ tweets or actively engaging them by sending interesting things their way or mentioning their work is a good way to break the ice. Linking fellow scholars or other professionals is an effective way to grow a network, and a service to the field. While it is important to avoid overdoing parochial tweets about subjects that are only relevant within a very small circle, for example directing comments to students, live tweeting departmental seminars and talks, re-tweeting the university's PR account, talking about local weather, etc., a smattering of personal tweets can give texture to a professional academic account. Indeed, among digital media experts, “a mixture of about 30% chatter and 70% content is the gold standard.”Footnote 20 It is important to resist the temptation to overdo self-promotion on Twitter. This may sound redundant given that self-promotion is a major feature of social media, but it has to be used sparingly. Sharing every message in which someone says something nice about your work or merely mentions your name quickly becomes irksome for your followers. An article, and especially a book, coming out in print is an occasion for celebration that all scholars can empathize with. But only the author knows the blood, sweat and tears that went into its making, its importance on the job market or for the tenure file; others are much less likely to forgive obsessive tweeting about it.

China Scholars’ Experiences Using Twitter

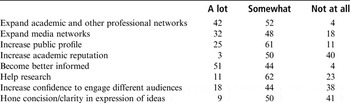

In order to investigate the experiences and attitudes of China scholars who use Twitter, I sent out an online survey by email. This elicited 98 responses, which represents about one-third of the China scholars using Twitter. Of this cohort of respondents, half reported using Twitter for more than two years, with a further third starting between one and two years previously, and 15 per cent were new-comers with less than a year's experience. Among all respondents, 44 per cent reported using Twitter for up to an hour every day, with 5 per cent spending more than an hour; however, 40 per cent spent less than 15 minutes on Twitter each day. The vast majority of scholars (91 per cent) said that they use Twitter to collect information and keep up to date with current events. Around three-quarters of scholars share links and related materials, publicize their own activities and connect with other China scholars. Around two-thirds use Twitter to connect with China-focused professionals in other sectors. Respondents were less concerned with using Twitter to promote their institution's activities, and less than one-third use Twitter for non-professional purposes. A picture thus emerges of China scholars using Twitter as a means to gather intelligence, network and, in marketing parlance, to build their personal brand. According to the survey, 81 per cent of users were distracted from other tasks by Twitter and 30 per cent reported having been drawn into arguments or attacked for their opinions. One-fifth of respondents said that they have to sacrifice other activities in order to make time for Twitter. One in ten scholars felt that their managers frown upon it. Asking respondents to identify how much Twitter has helped them to develop certain competencies, more than half said that it had helped them to become a lot better informed, while 42 per cent said that Twitter helped them to expand their academic and professional networks a lot; however, 40 per cent thought it had not helped their academic reputations at all. Table 2 sets out the rest of the responses.

Table 2: How Much Has Twitter Helped You to…? (%)

In addition to the survey, I asked respondents a number of open-ended questions. First, I sought to understand whether using Twitter had changed the way these scholars acquired and consumed information. Several colleagues noted how Twitter broadened the scope of the information they receive, allowing them to keep up with recent scholarship, activities in the field and “provid[ing] greater avenues for collecting, verifying and consuming information.” With the careful selection of people to follow, Twitter helped some colleagues to save time, allowed the consumption of timely materials and exposed them to a broader spectrum of sources, thereby introducing them to new ideas and teaching materials. One colleague noted the benefit of experiencing breaking events like the “umbrella” movement and exposure to many more views than those represented in news reports. Positive networking effects were noted by many respondents, one of whom commented that Twitter has “provided me with a wider network than I could ever achieve in real life.” Another colleague liked the “serendipity of Twitter, the clash of completely different ideas, sparking the generation of new ones.” These are certainly positive features of Twitter but, as noted above, it demands time that would perhaps be better spent on the traditional currency of academia, notably publishing. I thus asked colleagues to comment on whether they had noted any effects on their scholarly productivity since they had started using Twitter. Some colleagues noted that becoming established on Twitter, and learning how to use it most effectively, had had a negative impact on their productivity, particularly in the short term. Many respondents mentioned time demands, and it is clear that even for the enthusiastic users in this sample (96 per cent of those surveyed said that they would recommend Twitter to other academic colleagues), using Twitter can be a time-consuming distraction that has to be carefully managed. However, some suggested that being active on Twitter had increased their productivity by leading to collaborations and increasing the feeling of “being in touch” with developments in the field and on the ground. Others noted how access to resources sent their way on Twitter had enhanced their teaching, led to more “robust bibliographies,” and sparked ideas for research. At least one scholar's experience on Twitter “altered the way [they] think about scholarly productivity.” And, despite the dangers of consuming valuable time, “plenty of academically productive people are on [Twitter].”

Alongside these positives, several colleagues noted concerns about publicly expressing views on China, particularly on “sensitive” issues, for fear of complicating their access to the country or collaborators within mainland China, or of attracting the unwanted attention of nationalist or paid Chinese commenters. Other colleagues mentioned peers frowning on Twitter as a waste of time or as a tool for crass self-promotion. Summarizing a major theme that the currency in HE remains academic publications and research income, one respondent remarked that “posting actively on Twitter won't help me write my book [or] count for my tenure and promotion file.” A major issue was information overload and the pressure to be “always on.” Other colleagues noted tensions between rapid-response Twitter commentary and the cautious pace and careful consideration of scholarly practice. Some resented the idea of sharing insights that amounted to “giving something good away for free” and even “helping the competition out, i.e. other scholars.” Numerous respondents shared the view that Twitter is an effective way of “building a public-facing online presence,” and “finding confidence in your own voice,” with the caveat that “if you are prone to saying dumb things, then it is best not to tweet, whatever your academic rank.” One colleague suggested that Twitter was useful for “mak[ing] your university's public relations people aware of your presence, as well as your chair and dean – they love talking about their faculty using social media like Twitter for scholarly and teaching purposes.” Another respondent had excellent advice on keeping “a community-minded approach […] sharing, highlighting, and promoting colleagues’ work [since] generosity is key to fostering a vibrant scholarly community that benefits everyone.”

Conclusion

A substantial number of China scholars have adopted Twitter as a tool for publicizing their work, gathering intelligence and joining the public conversation. China scholars at various career stages, including PhD students, have used Twitter to raise their public profiles and make connections with fellow scholars and other China professionals. As external engagement beyond the academy becomes a routine expectation for scholars in many Western universities, social media have become a useful academic tool. However, despite the apparent simplicity of social media platforms like Twitter, it can be time consuming, distracting and incompatible with scholarly routines and norms. The utility of social media is an individual decision based on numerous variables, and social media are certainly not for everyone. However, for China scholars who are searching for an effective means to expand their external engagement profile, Twitter has proven useful. One area where Twitter is particularly potent is in creating opportunities for media engagements, as demonstrated by my student's experience, related above. In previous research examining the relationship between China scholars and the media, one major piece of advice from journalists to China scholars looking to expand their media profile was to use Twitter.Footnote 21 Hundreds of China correspondents routinely use Twitter and find it to be an effective tool for identifying scholars to interview. Producing concise, accessible comments on current and upcoming issues is an effective way to demonstrate expertise and establish useful connections and reputation among the media as well as among other China professionals and academic peers.

Biographical note

Dr Jonathan Sullivan is director of the China Policy Institute, and associate professor in the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Nottingham. He tweets @jonlsullivan.