Article contents

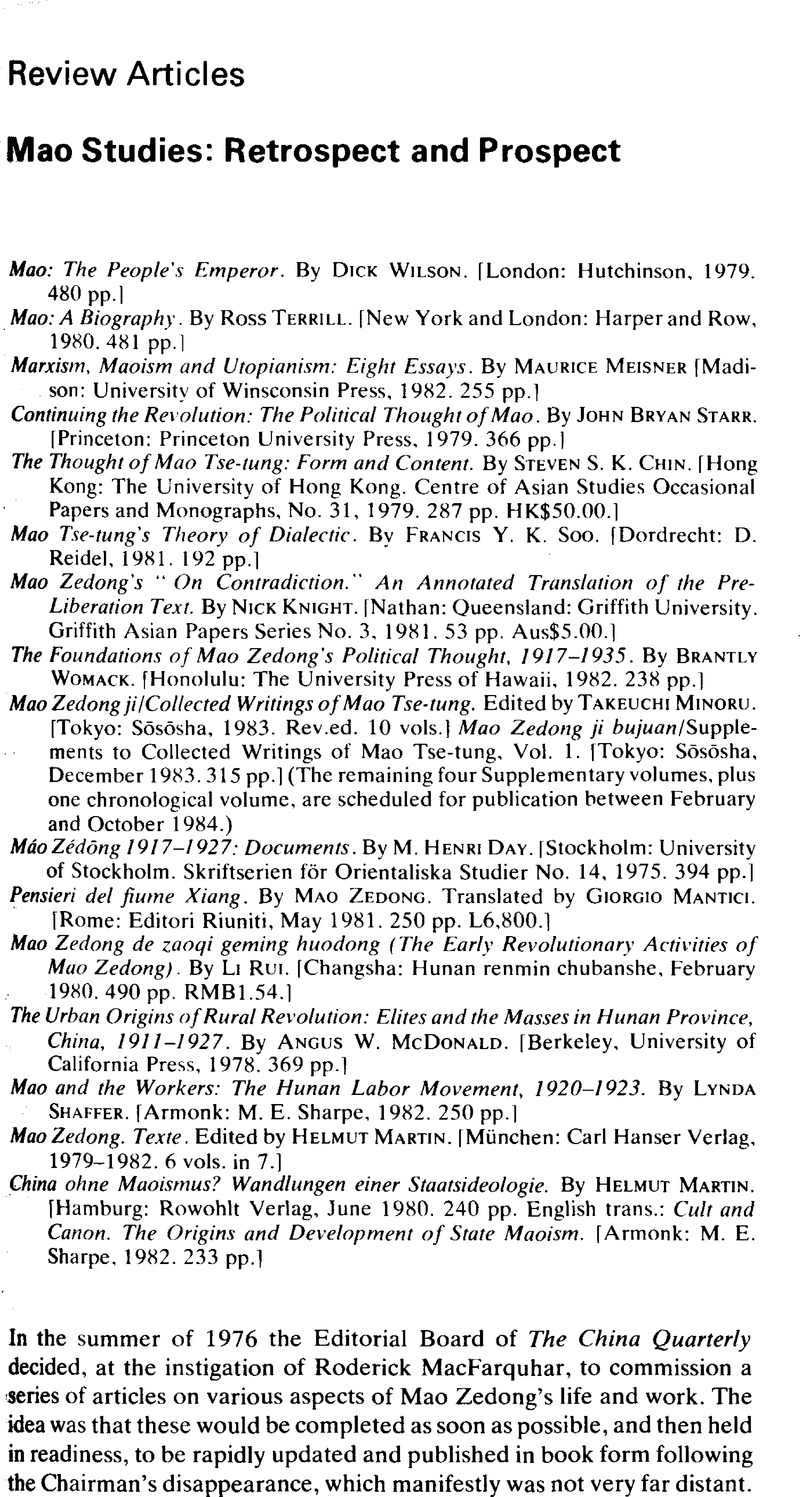

Mao Studies: Retrospect and Prospect

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 17 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The China Quarterly 1984

References

1. Rozman, Gilbert, “Moscow's China-watchers in the post-Mao era: the response to a changing China,” The China Quarterly, No. 94 (06 1983), pp. 215–41CrossRefGoogle Scholar;

2. See, in particular, his article in The China Quarterly, No. 68 (12 1976), pp. 751–77CrossRefGoogle Scholar;

3. Dangshi yanjiu. No. 2 (1980), p. 77Google Scholar;

4. Meisner, M., “Leninism and Maoism: some populist perspectives on Marxism-Leninism in China,” The China Quarterly, No. 45 (03 1971), pp. 2–36CrossRefGoogle Scholar;

5. See The China Quarterly, No. 87 (09 1981), pp. 407–439CrossRefGoogle Scholar;

6. d'Encausse, H. Carrère and Schram, S., Marxism and Asia (London: Allen Lane, The Penguin Press, 1969), p. 293Google Scholar;

7. The China Quarterly, No. 68 (12 1976), pp. 845–48CrossRefGoogle Scholar;

8. Wan-sui (1969). pp. 192–93; Miscellany of Mao Tse-tung Thought, p. 96.

9. In fairness to Chin, it should be noted that authors rather more learned than he in Marxist philosophy put forward similarly extravagant views in the early 1970s; thus Martin Nicolaus asserted, in his Foreword to the Grundrisse, that Mao's “On Practice”and “On Contradiction” were “at the same time strictly orthodox … and highly original,” and remained “the classic exposition of materialist dialectics as a whole, the standard against which all other writings must be measured and which will probably remain unequalled for a very long time.” Grundrisse (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1973), p. 43Google Scholar;

10. As originally published in The New Republic, 27 February 1965. this disclaimer was strong, but Mao carefully edged away from a flat statement that he had never given any such lectures. (”… he had no recollection of having written any such work and he thought he would not have forgotten it had he done so.”) When the interview was re-published as an appendix to The Long Revolution (London: Hutchinson, 1973. p. 207)Google Scholar; it was “improved” to make of it a categorical denial of authorship.

11. See. for example. Mao Zedong zhexue sixiang (zhailu). (I Mao Zedong's Philosophical Thought – Extracts) (Beijing: Department of Philosophy of Beijing University, 1960). 581 ppGoogle Scholar; passim. (The lectures on dialectical materialism are broken up into sections by theme and distributed throughout the volume.)

12. See the materials in Zhongguo zhexue. Vol. 1 (n.p.. 1979), pp. 1–44Google Scholar;

13. Knight, Nick. “Mao Zedong's On Contradiction and On Practice: pre-liberation texts,” The China Quarterly, No. 84 (12 1980), pp. 641–68CrossRefGoogle Scholar;

14. The China Quarterly, No. 49 (03 1972), p. 88CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

15. Yi Da qianhou (Before and After the First Congress) (Beijing: Renmin chubanshe, 1980), 2 vols.Google Scholar; Xinmin xuehui ziliao (Materials on the New People's Study Society) (Beijing: Renmin chubanshe. 1980)Google Scholar;

16. The China Quarterly, No. 46 (06 1971), pp. 368–69Google Scholar;

17. See. for example, Shubai, Wang and Shenheng, Zhang, “Qingnian Mao Zedong shijieguan de zhuanbian” (“The transformation in the world view of the young Mao Zedong”), Lishi yanjiu. No. 5 (1980). p. 83Google Scholar;

18. Jui, Li, The Early Revolutionary Activities of Comrade Mao Tse-tung. Translated by Sariti, Anthony W.. Edited by Hsiung, James C.. Introduction by Schram, Stuart R.. (White Plains, NY.: M. E. Sharpe, 1977)Google Scholar; For a review see The China Quarterly, No. 76 (12 1978), pp. 915–18CrossRefGoogle Scholar;

19. For a brief and discreet evocation of these events by Rui, Li himself see his article “Zongli zai wo xin zhong” (“Premier [Zhou] as I remember him in my heart”), Renwu, No. 5 (09 1982), pp. 14–18Google Scholar;

20. See MacFarquhar, Roderick, The Origins of the Cultural Revolution, Vol. II (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983), p. 397, n. 29, and p. 409, n. 228Google Scholar;

21. Edgar Snow, letter to the author dated 19 July 1965.

22. Schram, S.. The Political Thought of Mao Tse-tung (New York: Pracger, 1969), p. 208Google Scholar; (emphasis added).

23. Fitzgerald, John. “Mao in mufti: newly-identified works by Mao Zedong,” The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs, No. 9 (01 1983). pp. 1–16CrossRefGoogle Scholar; This pen name was, ft however, listed, along with several others, in a note giving such names for Mao and other leaders published in Dangshi yanjiu ziliao. No. 2 (Sichuan: Renmin chubanshe, 09 1981), pp. 796–97Google Scholar;

24. Schram, S., “New texts by Mao Zedong,” Communist Affairs, Vol. 2, No. 2 (04 1983), pp. 144 and 149–50Google Scholar: for the full text, which appeared in Gongchandang on 27 December 1920, see Yi Da qianhou, pp. 208–209.

25. Schram, S., Mao Zedong: a Preliminary Reassessment (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1983), p. 4Google Scholar; Supplement, Vol. I, pp. 19–23. For a reference to these tetters, see Li Rui, p. 28.

26. Mao Zedong shuxin xuanji (Selected Letters of Mao Zedong) (Beijing: Renmin chubanshe, 1983)Google Scholar; For a description, and extracts in translation, see Beijing Review, No. 52 (1983), pp. 14–19 and 26Google Scholar;

27. Conversation of 7 May 1982 at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. I Institute of Marxism–Leninism Mao Zedong Thought, of which Professor Liao was then deputy director.

28. Shoudao, Wang. “Guanyu dangshi renwu yanjiu de jige yijian” (“Some views about research on individuals in Party history”), Renmin ribao, 9 12 1983, p. 5Google Scholar;

29. The China Quarterly, No. 86 (06 1981), pp. 350–52CrossRefGoogle Scholar;

30. Schwartz, Benjamin I., “China and the west in the ‘Thought of Mao Tse-tung,’” in Ho, Ping-ti and Tsou, Tang (eds.), China in Crisis, Vol. I (Chicago: University of Chicagof Press, 1968), p. 367Google Scholar;

31. Haisheng, Li, “Shi lun Mao Zedong zhexue sixiang cong Zhongguo lishi wenhua yichan zhong jiqu suyang de tedian” (“A tentative discourse on the characteristic of Mao Zedong's philosophical thought consisting of drawing nourishment from the heritage of Chinese history and culture”), Shehui kexue. No. 10 (1983), p. 18Google Scholar;

32. Renmin ribao, 14 November 1983. p. 1. The account in Beijing Review. No. 48 (28 11 1983), pp. 5–6Google Scholar; is briefer, and omits some of the key points mentioned here.

33. Yaobang, Hu, “The best way to remember Mao Zedong,” Beijing Review, No. 1 (2 01 1984), pp. 16–18Google Scholar; The article was originally published in Renmin ribao, 26 December 1983, p. 1. Further details regarding the line laid down at the Nanning conference can be gleaned from an article by Qi, Wang, a leading figure in the CCP's Party History Research Centre (of which Liao Gailong is vice-chairman), “Inheriting and developing Mao Zedong thought,” Beijing Review, No. 52 (26 12 1983). pp. 20–26Google Scholar;

- 2

- Cited by