In the summer of 1973, East Germany hosted a much anticipated socialist youth festival, the tenth World Festival of Youth and Students, which many subsequently referred to more simply as the Red Woodstock. Under the banner of “anti-imperialist solidarity, peace, and friendship,” the festival in East Berlin convened twenty-five thousand international participants, as well as hundreds of thousands of East German youths and guests, for nine days of music performances, art exhibitions, sports events, and political seminars—all in the name of international socialism.Footnote 1 Yet, in looking back at the events, participants and scholars alike would cast the festival as a “break” or momentary rupture from the everyday realities of really existing socialism.Footnote 2 Ina Merkel, a young attendee who became a scholar of East German cultural studies, later reflected: “I think that afterwards everything was as before … I believe that, for the young people who had taken part in it, it had been a very important experience in their lives. And, for them, a return to normality meant an awakening, also back to the restrictive situation. So they woke up again; they became depathologized again, i.e., the pathos of the revolution was gone.”Footnote 3 In recognizing the Red Woodstock as a singular moment embodying young people's international revolutionary zeal, Merkel points to its significance as an aberration rather than as a reflection of East German everyday life. Her comment reflects a common sentiment—namely, that the “revolutionary pathos” that the festival engendered might be understood as antithetical to the state socialist project.

Scholars often interpret festivals as aberrations or departures from the norm, as a time when society's creative potential is unleashed, before being once again stifled—or, in the East German case, redisbursed to the hidden niches of society.Footnote 4 Such notions have their antecedents in studies of the European carnival of the Middle Ages and Renaissance period. In his seminal account, Rabelais and His World, Soviet theorist Mikhail Bakhtin—whose work remains influential in postsocialist theory—highlights an image of the carnival in which the world was turned “upside down.” He suggests that “the carnival celebrated temporary liberation from the prevailing truth and from the established order; it marked the suspension of all hierarchical rank, privileges, norms, and prohibitions.” As Bakhtin further points out, “this temporary suspension, both ideal and real, of hierarchical rank created during carnival time a special type of communication impossible in everyday life.”Footnote 5 In essence, the carnival of the Middle Ages—like the festival of the modern era—was depicted as embodying a departure from everyday societal structures, representing a fleeting moment of authentic individual expression, genuine performances, and unhindered lived experience.

This article sets out to destabilize the idea that the 1973 festival exemplified a subversion of everyday life, by instead conceptualizing the Red Woodstock as a moment of globalized influences and youth engagement that reflected not only shifting societal norms, but also the East German state's commitment to international solidarity.Footnote 6 On the one hand, this reassessment of the Red Woodstock enables us to move beyond flattened depictions of the festival as a false rendering of East German society.Footnote 7 Stefan Wolle, for instance, argues that the festival served as little more than a “Potemkin Village,” with the ever-present security apparatus of the police and Ministry for State Security (MfS, or Stasi) disciplining the festival participants from behind the scenes.Footnote 8 On the other hand, this reinterpretation allows us to recognize the festival as more than a rare instance of authentic interactions between East Germans and the world at large, as Ina Merkel and Ina Rossow have depicted it (though Merkel recognizes the festival's significance in establishing an East German ritualized youth culture as well).Footnote 9 The problem with such interpretations is that modern festivals are seldom short-lived moments of controlled chaos, but rather deeper reflections of state and societal rituals, youth trends and behavior, as well as the ever-shifting boundaries of “imagined communities.”Footnote 10 The revolutionary pathos or “upside-down” character of the festival should thus be understood as far from external to socialist society; rather, it proved inherent to the very conceptualization of the East German late socialist project. This rethinking of the festival sets in sharp relief the extent to which one of the East German state's ongoing challenges resulted from its own embrace of international socialism.

Rethinking East German Socialism through a Postsocialist Lens

This article draws on the work of postsocialist scholars to understand state socialism beyond the search for what Anna Krylova refers to as the “tenacious liberal subject” that dominates Western analyses of the Eastern bloc.Footnote 11 The postsocialist approach is further germane for rethinking the public/private, official/unofficial, or authentic/inauthentic divides that borrow from Jürgen Habermas's notion of the “public sphere” and that remain central to liberal assessments of state socialism.Footnote 12 To that end, the article deliberately replaces the idea of the public sphere with a focus on socialism's real and imagined public spaces. Public spaces might be understood as representing what Uta Staiger has referred to as “individual and collective configurations of subjectivity” that are “organized spatially and symbolically in the city through imaginaries invested in shared, public places.”Footnote 13 By tracing configurations of subjectivity across public spaces, we gain insights into how individuals not only imagined themselves as part of broader communities, but also into how they elided the “official versus unofficial” and “authentic versus inauthentic” divisions that scholars tend to inscribe onto state socialist projects.

This analytical reframing of socialist public space at the local level is further informed by postsocialist interventions concerning the problematic renderings of the Cold War globally. In her theorization of state socialism, Katherine Verdery argues that the Cold War produced “a form of knowledge and a cognitive organization of the world.” As such, it laid down the “coordinates of a conceptual geography grounded in East vs. West [with] implications for the further divide between North and South.” As Verdery goes on to note, “mediating the intersection of these two axes were socialism's appeal for many in the ‘Third World’ and the challenges it posed to the First [World].”Footnote 14 Despite Cold War geopolitical divisions, individuals, ideas, and cultural expressions did traverse both the East-West and North-South boundaries. International solidarity proved to be one vehicle for such transgressions, whereby the East German state intentionally brought the outside world into the German Democratic Republic (GDR).Footnote 15 In turn, East German youths often viewed themselves as part of an international youth culture that cut across ideological and sociopolitical movements—from countercultural activities in the West, to solidarity networks with revolutionary actors, including the Vietnamese, Chileans, Palestinians, as well as Black Power groups, in the Atlantic World.Footnote 16 It was, in this respect, that East German international solidarity embedded global lexicons of resistance, both real and imagined, in local public spaces during the 1973 Red Woodstock, with lasting repercussions well beyond the festival.

As a word of caution, we should be wary of idealizing East German imagined communities, especially since actual state-generated solidarity projects were mired in contradictions. Such inconsistencies emerged because the East German state reinforced the established demarcations between the East and West, as well as between the North and South—despite its commitment to an antifascist and anti-imperialist agenda. Moreover, East German citizens also recognized their “East Germanness” against an “other” in ways that underscored negative conceptions of class, race, and sexual difference, all of which remained deeply embedded in the East German social fabric.Footnote 17 In the postcolonial era, this phenomenon was not unique to East Germany; Western states engaged in their own “othering” processes. Yet, in the case of East German society, it was especially problematic, as it demonstrated the extent to which the state's proclaimed antifascist origins, as well as its anti-imperialist agenda, had serious limitations. The following discussion makes clear how youths, at times, reinforced, and, at other times, rejected the gendered, sexualized, and racialized tropes that remained intrinsic to the structuring of East German public spaces.

A Brief History of the Socialist World Festivals

The first World Festival of Youth and Students took place in Prague in 1947, with subsequent festivals occurring every other year through the mid-1960s, after which they became slightly less frequent. Transnational by nature, they were organized by two socialist-leaning, non-government organizations—the World Federation of Democratic Youth (WFDY) and the International Union of Students (IUS)—both of which supported international and national preparatory committees with the organization of events on the ground in locations as far-flung as Budapest, Helsinki, Havana, Moscow, and East Berlin.Footnote 18 By the 1960s, the festival themes reflected the aspirations of the Soviet Union and, by extension, the Eastern bloc countries to forge connections with Third World state and non-state actors in the aftermath of the rapid wave of decolonization across the global South. In projecting international solidarity across time and space, the festivals came to embody a socialist ritual that travelled from one city to the next, collapsing the local versus global divide.

While a demonstration of socialism's internationalism was at least part of the impetus for the festival's mobile character, its ability to be rooted temporarily in local spaces also served a strategic purpose. East Berlin, for instance, represented a particularly important site for the festival, as it symbolized a key “border region” during the Cold War.Footnote 19 This designation refers to the idea that the divided city of Berlin—located deep within the East German state—served as both a concrete and imagined point of interaction between the “East” and “West” during the Cold War. In fact, the World Youth Festival had been held once before in East Berlin—in 1951.Footnote 20 At the time, the presence of international youths had undoubtedly served to reinforce the East German state's claim to legitimacy in the face of the West German state's refusal to recognize it.Footnote 21 Countering West German isolation efforts, the 1951 festival program underscored the East German state's foundational myth, by aligning the GDR's proclaimed antifascist origins with a commitment to anti-imperialist struggles in the Third World.Footnote 22

By contrast, the 1973 festival in East Berlin took place during a period of relaxation between the East and West. Rather than seeking to legitimize the GDR, state planners recognized the 1973 festival as indicative of the very spirit of détente that had come to mark the shift in East-West German relations after the recent signing of the Basic Treaty. That agreement had not only established “neighborly relations” between the two German states, but also paved the way for widespread recognition of the GDR beyond the Eastern bloc, ending the decades-long struggle for legitimacy that East and West Germany had fought through diplomatic and trade agreements in the Third World. As the West German weekly Der Spiegel reported, the 1973 festival seemed to embody “the openness, even opulence with which, this week, the GDR presented itself before the rest of the world and its own people.”Footnote 23 Yet, despite East Germany's improved international standing, the preparations for the 1973 festival reflected the East German authorities’ continued concern with perceived internal and external threats that were, in many respects, exacerbated—rather than diminished—by the relaxation in East-West tensions.

The Grotesque Body between Everyday Life and the Festival Space

In laying the groundwork for the festival, the state adopted measures aimed first and foremost at cleansing the East German capital of so-called “asocials” or “outsiders.” According to Peter Stallybrass and Allon White, “outsiders are constructed by the dominant culture in terms of the grotesque body.” Yet, as Bakhtin makes clear in his rendering of the medieval festival, “the grotesque body … has its discursive norms too: impurity (both in the sense of dirt and mixed categories), heterogeneity, masking, protuberant distension, disproportion.”Footnote 24 Such conceptions of outsiders were far from foreign to state socialism. In the months preceding the festival, East German authorities had sought to cleanse so-called asocial elements that had long laid claim to the East German capital. To achieve this end, the state adopted two specific measures: the criminalization and incarceration of “asocial,” as well as other, citizens; and the reinforcement of the border regime through increased security measures designed to monitor the movement of “outsiders.” The preparation for the festival thus assumed an internal logic rooted in the East German state's long-standing practice of seeking to purge the “grotesque” in order to achieve the optics of ideological conformity in public spaces.

Well in advance of the festival, the police forces and the Stasi coordinated efforts to remove so-called criminal youths, the mentally ill, and sex workers who lived in or frequented the city.Footnote 25 The state arrested between 1,700 and 2,300 people, with many categorized as “asocials” and “hooligans”; roughly another 2,500 fell under increased surveillance. An additional 800 individuals found themselves banned from East Berlin in the months preceding the festival.Footnote 26 The state also heightened security measures with the deployment of roughly 4,000 official and unofficial MfS personnel to prepare for the festival events. The East German Volkspolizei (People's Police, or VoPo) were assigned to monitor the streets of East Berlin, some wearing uniforms, others in plain clothes or in the blue shirts of the Freie Deutsche Jugend (Free German Youth, or FDJ).Footnote 27 In addition, the state recruited members of the FDJ to support the security forces charged with maintaining order at the events.Footnote 28

At the border checkpoints between East and West Berlin, East German authorities focused on halting the entry of so-called right-wing extremists, i.e., conservative West German youths, as well as “left-wing extremists,” namely, Trotskyites and Maoists. They also confiscated materials that youths and other visitors attempted to smuggle into the festival. A Stasi report from July 30 noted, for example, that, in the midst of the festival, a couple of hundred “left-wing extremists” had attempted to travel across the Friedrichstraße train station from West Berlin to East Berlin. The individuals included members of the League against Imperialism and other communist groups from West Berlin, who planned to distribute pamphlets at the festival. They had concealed the materials beneath their clothes, especially below the waist and on their backs. Operating under the assumption that the border guards would target male individuals, they relied heavily on female members of the group to carry the pamphlets. In the end, many of the leftists were denied entry by GDR border guards; yet, as the report acknowledged, at least some of the individuals managed to make it through to distribute the pamphlets.Footnote 29

Despite such heightened security measures, a steady stream of people and politically “subversive” materials did flow each day across the border into East Berlin.Footnote 30 Indeed, as scholars have acknowledged, the East German state only succeeded to a certain degree in disciplining the people and the lived spaces they inhabited.Footnote 31 The festival was certainly no exception. As the state opened up the “cleansed” city to hundreds of thousands of youths and visitors, those who occupied public spaces reimagined the socialist ideal in their own image, rendering it once again open to reinterpretation. The process began with the steady stream of bodies and subversive materials across the border, and it continued with individual and collective acts of performativity that participants carried out during the festival.Footnote 32

To be sure, the East German authorities aimed to ensure ideological conformity among their own youths, introducing a GDR-wide educational program in the year leading up to the festival.Footnote 33 Yet, international solidarity was not something that could be achieved through propaganda alone. Rather, it required a process of ritual embodiment via youth performances in festival activities—including the parades, rallies, meetings, and sporting events—that were to take place in East Berlin. The presence of hundreds of thousands of East German youths in blue FDJ shirts reinforced the state's desire for a visual aesthetic of order through the collective assembly of their uniformed bodies. Yet, at the same time, it was the presence of international guests alongside East Germans that was essential for transforming the concrete East Berlin cityscape into the imagined international socialist ideal. As the official FDJ youth newspaper, Junge Welt, reported, delegations presented themselves with “colorful national costumes and clothes, balloons, flowers, giant banners, flags. Rhythmic dances with a genuine Latin American or African temperament enraptured the onlookers with true enthusiasm.”Footnote 34 Such descriptions, alongside full-page collages of international youth in their traditional costumes, reflected the aesthetic of heterogeneity that the East German authorities sought to achieve during the festival.

This performative aspect of the solidarity discourse proved fundamental to the state planners’ vision: in essence, international solidarity could only be realized through the diversity of the festival participants’ bodies present in the festival space. In assessing earlier festivals, Quinn Slobodian refers to the state's carefully cultivated images of heterogeneity as “a mode of visual representation that could be called socialist chromatism.” He goes on to note that, “within the larger idiom of socialist realism, socialist chromatism relied on skin color and other markers of phenotypic difference to create (overly) neat divisions between social groups within a technically nonhierarchical logic of race.”Footnote 35 According to Slobodian, such images underscore the paradoxes of East German socialism insofar as the state claimed to erase difference, while reinforcing a process of “othering” in a “Saidian” sense, with the festival serving as a key representation of the socialist chromatic ideal.Footnote 36 Yet, images of heterogeneity built on “(overly) neat” racial divisions become harder to trace when shifting from the state-generated motifs of the festival to activities on the streets of the city. Somewhere along the way, the state discourse often became dislodged. This process occurred as the state agenda was appropriated, shifted, and ultimately transformed by those who engaged with it.Footnote 37 While taking on a singular meaning in the state newspapers, socialist internationalism took on new connotations when international guests—such as Angela Davis or Yasser Arafat, who attended the festival as the heads of their respective countries’ delegations—adopted it in their public appearances and speeches.

At the 1973 festival, Davis and Arafat represented both distinguished guests and the classic embodiment of the “other” that the state sought to celebrate, yet control. As a critical rereading of Bakhtin suggests, one encountered during the festival—like the carnival—a “mobile, conflictual fusion of power, fear and desire in the construction of subjectivity: a psychological dependence upon precisely those Others which are being rigorously opposed and excluded at the social level.”Footnote 38 At the Red Woodstock there was a double-othering process at play, with both the cleansing of the internal subversive elements and the controlling of perceived external threats; yet, in turn, both used the heterogeneity of the festival to open up the solidarity rhetoric and public spaces through their embodiment of the festival ideal. Rather than rendering the festival as authentic or inauthentic, their individual yet collective assertion of subjectivity enabled what one might refer to as diverse “imaginaries invested in shared, public places.”Footnote 39

Solidarity across Public Spaces: The Cases of Angela Davis and Yasser Arafat

Beginning in the early 1970s, the East German state honored Angela Davis as a key spokesperson of the “other America” and as a powerful symbol of the Black Power movement. She became an icon in the GDR after her imprisonment in the United States on charges of having indirectly aided in an armed hold-up of a courtroom in California to free the “Soledad brothers”: George Jackson, Fleeta Drumgo, and John Clutchette, who were accused of murdering a guard at Soledad prison. While Davis was incarcerated, the East German state organized exhibitions and campaigns, such as “One Million Roses for Angela Davis,” with East German youths sending solidarity postcards and letters to the prison where she was being held. The East German leadership also placed pressure on the American judge who ruled on her case, reminding him that the international community would assess US race relations based on the outcome of the trial. When Davis was finally acquitted, the East German Socialist Unity Party (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, or SED) called the verdict a victory for the socialist solidarity cause.Footnote 40 Davis also recognized the importance of the international campaign, writing in her autobiography that her freedom had been secured through “nothing more and nothing less than the tremendous power of united, organized people to transform their will into reality.” Shortly after her release, she travelled to the socialist bloc—as well as to Cuba and Southeast Asia—declaring that “the international campaign had not only exerted serious pressure on the [US] government, it had also stimulated the further growth of the mass movement at home,” i.e., in the United States.Footnote 41

Davis certainly had limited control over how the East German authorities utilized her image in state-generated propaganda. As Katrina Hagen points out, one East German publication went so far as to fetishize her beauty and her “Afrika-Look,” rendering Davis a symbol of the state's international solidarity campaign, which played up a “level of affect and desire as well as political conviction.”Footnote 42 Such exoticizing discourses reflected the GDR's deeper societal norms regarding the racialized and sexualized “other.”Footnote 43 But it is important to avoid reducing Davis to a static symbol constructed through a flattened East German discourse on race and gender; rather, as seen during the festival, Davis willingly assumed the position at the head of the US delegation that travelled to the other side of the so-called Iron Curtain to lay claim to a solidarity movement that had both local and global orientations. In turn, her participation at the Red Woodstock defined the very essence of the “pathos of a revolutionary ideal” that had come to dominate the festival spaces, reinforcing the East German state's international solidarity agenda, yet also subtly transforming it in her own image.

Fig. 1. Angela Davis, front and center, on stage at the 1973 festival. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-M0804-0717 / Photo Credit: Dieter Demme.

Over the years Davis had attended a number of socialist youth festivals. In her autobiography, she recalls her participation in the 1962 World Festival of Youth and Students in Finland, recounting vividly her awe at the Cuban revolutionaries:

It is not easy to describe the strength and enthusiasm of the Cubans. One event however illustrates their infectious dynamism and the impact they had on us all. At the end of their show, the Cubans did not simply let the curtain fall … Those of us openly enthralled by the Cubans, their revolution and the triumphant beat of the drums rose spontaneously to join the conga line. And the rest—the timid ones, perhaps even the [CIA] agents—were pulled bodily by the Cubans into the dance… a dance brought into the Cuban culture by slaves dancing in a line of chains.Footnote 44

Such personal experiences likely reinforced Davis's decision to serve as the head of the US delegation at the East Berlin festival in 1973, where she expressed her conviction that being in a socialist country surrounded by international youth would have a profound effect on the young delegates from the United States. Taking the microphone in Café Moskau, she proclaimed that this next generation of left-leaning youths would incite “new important initiatives of the anti-imperialist struggle.”Footnote 45 The power of Davis's presence, coupled with her faith in the revolutionary potential of the younger generation, transformed what might have been a scripted rendering of solidarity at the official level into one that instead contained diverse interpretations, as well as competing subjectivities in the festival spaces.Footnote 46

On the final day of the Red Woodstock, Davis assumed the role of spokesperson for the festival youths, issuing an “Appeal to the Youth of the World” in which she declared: “We know imperialism. That is why we are strengthening our actions and our struggle, uniting our efforts and consolidating our cooperation, to make the pursuit of peace and social progress unstoppable …”Footnote 47 Over the years, Davis had positioned herself as a powerful, unapologetic supporter of socialist solidarity, giving voice to a variant of it that instilled such rhetoric with elements of anti-imperialism, Black Power, and youth internationalism. In making the appeal, Davis was probably less concerned with legitimizing the GDR's solidarity agenda per se, than with projecting her message as it intersected with that of the socialist state. Having fought against the injustices of a system marked by social and racial inequalities in the United States, Davis recognized the importance of the East German solidarity cause; yet, she arguably also imparted a decidedly anti-statist revolutionary bent to the international socialist struggle. Despite the East German authorities’ careful wording and even molding of Davis's image, the solidarity agenda might therefore be understood as having assumed multivalent meanings, as Davis and others expressed their own versions of it during the festival.

At the time of the events in East Berlin, many East German youths not only recognized Davis from the frequency of her image in state propaganda, but were also familiar with her affective force, thanks to her prior visits to the GDR.Footnote 48 Davis had first made her way across the “Iron Curtain” in the late 1960s, during her time as a student in West Germany. After the end of her trial in 1972, she returned to the GDR, where she was granted an honorary degree from the Karl Marx University in Leipzig—an accolade similar to those that the East Germans had previously conferred on other American civil rights activists, including W. E. B. Du Bois, the cofounder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and Paul Robeson, an African American musician, actor, and activist. By the time of the 1973 festival, Davis was thus a familiar face to most East German youths, many of whom had written her letters, welcomed her at rallies, and listened to her speeches. In the years following the festival, Davis would return to East Berlin in 1975 to participate in the socialist World Congress of Women, which occurred in conjunction with the United Nations International Women's Year. When a delegation of African American editors and publishers visited the GDR that same year, one of them noted that Davis was recognized as nothing less than “a folk heroine by [East German] students because of her fight for the downtrodden.”Footnote 49 This image was partially generated by East German state propaganda, but it was also a result of the revolutionary zeal that Davis herself expressed during her participation in the international solidarity events, the 1973 youth festival, and the 1975 women's congress.

Though less well-covered than Davis in the East German media (as well as in recent historical accounts), Yasser Arafat was a second prominent guest at the 1973 festival who bolstered, yet also laid claim to, the East German solidarity discourse through his and the Palestinian delegation's participation in the events. In the year preceding the festival, Arafat had established a working relationship with the East German authorities, turning to them for political, material, and military support for the Palestinian cause. Yet, his invitation to the 1973 festival proved to be a pivotal moment in solidifying East German ties to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). In fact, Arafat used the occasion to discuss with SED leader Erich Honecker the opening of a PLO consular office in East Berlin, ensuring diplomatic relations between the GDR and his organization, as well as material support for the PLO, in the years to come.Footnote 50 In an issue of Shu'un Filastiniya (Palestine Affairs) that came out just after the festival, Mahmoud Darwish pointed out that the “world is neither a single integrated unit, nor is it true that East is East and West is West. But we are part of an international revolutionary movement which has branches in both East and West … Palestine went to Berlin with its own hands; it has achieved moral independence.”Footnote 51 As Darwish observed, the festival created both a real and symbolic space in which the Palestinians could amplify the demands of the PLO by operating within the East German state-generated solidarity network.

East German support for the Palestinian cause was not an unburdened act. Whereas the West German state had sought to reconcile with the Nazi past through reparation payments and support for Israel, the GDR instead provided material and ideological backing to the Palestinian struggle. This decision was partially geopolitical in nature, given the Cold War bipolar division of the world into opposing ideological camps. But it also came about through a whitewashing of the German past, with East German leaders saddling their West German counterparts with blame for Nazi atrocities, as the heads of a country that was the supposed successor to the Third Reich. For young East Germans, especially those who had been born after World War II, the narrative of East German self-exculpation concerning Nazis’ crimes was coupled with state propaganda highlighting the GDR's support for Palestinian self-determination as part of its broader antifascist and anti-imperialist platform.Footnote 52 For them, East Germany's solidarity agenda with the PLO was thus, at least to some extent, stripped of its encumbered historical significance and instead shaped through the state's proclaimed antifascist foundational myth.

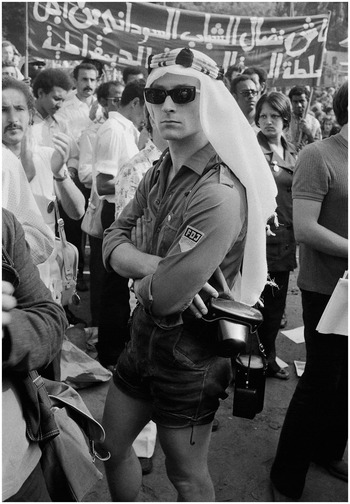

East German youths expressed solidarity with the Palestinian cause in ways that may still have unsettled the East German authorities. For instance, an FDJ participant—in his easily recognizable blue shirt—was photographed in front of an Arabic banner that read “Struggle of the Youth,” wearing a makeshift headscarf that resembled the traditional keffiyeh.Footnote 53 The East German's act of donning the keffiyeh involved an element of cultural appropriation: Arafat had begun wearing the well-known, black-and-white patterned keffiyeh in the 1960s, transforming it into a symbol of Palestinian resistance against the Israeli state. The keffiyeh subsequently gained international appeal, particularly among Western leftists who supported the PLO. Yet, despite being appropriated as a symbol that took on a somewhat Western, stylized affect, it nonetheless remained a visceral reminder of the revolutionary zeal of the Palestinian cause. For East German authorities, both aspects were likely viewed as somewhat antithetical to the state-socialist agenda.

Fig. 2. Youths on Alexanderplatz during the 1973 festival. Source: German Historical Museum Nr. 2011 165 / Photo Credit: Thomas Hoepker, Magnum Photos.

At the time, East German authorities were especially wary of the more violent factions of the Palestinian movement. In the lead-up to the festival, they had taken measures to avoid a possible terrorist attack by the Black September Organization (a breakaway militant faction of the Palestinian organization, Fatah), similar to the one the group had carried out during the 1972 Olympics in Munich.Footnote 54 As a result, Palestinians travelling to the 1973 festival faced increased security at the border crossings, and those already in the GDR were placed under heightened surveillance.Footnote 55 Given the Stasi's acute fear of Palestinian militant activities—as well as the SED's general concern with the potential radicalization of East German young people—the East German youth's donning of the keffiyeh may have thus been read as a performative act that teetered on the edge of the subversive. But relations between the PLO and the East German state had become increasingly beneficial for both sides by the beginning of the 1970s. For the East Germans, the connection was important because Arafat had positioned the Palestinians within the broader anti-imperialist movement of the Third World, aligning the PLO with other revolutionary struggles, from Vietnam to Algeria. As a result, the PLO cause fit well with the East German state's solidarity agenda, not least because the Chinese were, at the time, also vying for influence in the Middle East and Africa.Footnote 56 Arafat, in turn, condemned the 1972 incident in Munich and similar acts of terrorism, declaring that the “Palestinian people will fight with political, military and ideological and other methods, but are not prepared to engage in such senseless actions as hijacking of aircraft.”Footnote 57 Regardless of whether Arafat could deliver on such promises, he clearly hoped to allay the fears of the East German leadership by rejecting the violent tactics of the Black September Organization and by reaffirming his commitment to strengthening relations with the GDR.

The East German youth donning the keffiyeh was likely unaware, however, of the nuances of Cold War geopolitical developments; rather, the decision to put on the headscarf may have simply reflected the shifting subjectivities that young people assumed at the festival. In placing it on his head, he was not necessarily engaging in an act of open rebellion, but rather expressing a spontaneous act of solidarity that reflected the festival's spirit of cultural-political exchange. In fact, during the festival, over sixty thousand youths participated in a state-sponsored rally in support of the Palestinian cause and peace in the Middle East.Footnote 58 Such acts of solidarity did not exist alongside the official agenda of the East German state, but rather through it, since the two were intrinsically linked. In the years following the festival, such acts would take on alternative expressions, connecting East German subjecthood to youth internationalism via campaigns that continued to lay claim to the East German solidarity agenda, but in ways that subtly shifted or transformed it from the inside out.

The East Germans had welcomed Davis and Arafat in particular because they reinforced the state's international solidarity agenda at the festival; they were not, however, the only ones playing this role. During the Red Woodstock, East German authorities highlighted a number of other specific causes that would continue to play a central role in the GDR's ongoing solidarity agenda. For instance, the GDR honored participants from both North and South Vietnam as distinguished guests; the US retreat from the war in Vietnam served more generally as a cause for much celebration. Participants from around the world took part in a campaign to raise funds for the Kinderkrankenhaus Nguyen Van Troi, a children's hospital in Vietnam, further demonstrating the continued commitment that the socialist state intended to provide to the Vietnamese.Footnote 59 In the months following the festival, the GDR would turn its attention to other solidarity causes, with a heightened focus on supporting Chileans targeted by the right-wing military junta that brought Augusto Pinochet to power in Chile in September 1973. The campaign resonanated among many East German youths, not only as a result of the socialist state's propaganda, but also because a large delegation of Chileans had attended the 1973 festival, just weeks before the coup took place.Footnote 60

Fig. 3. Chileans at the 1973 Festival. Source: Bundesarchiv Bild 183-M0804-0760 / Photo credit: Jürgen Sindermann.

The East German state also supported a number of anti-colonial revolutionary movements in the festival program as part of its ongoing solidarity activities, including a powerful campaign against the apartheid regime in South Africa. East German support for the African National Congress (ANC) and the South West African People's Organization (SWAPO) had begun in the 1960s with the establishment of the GDR solidarity committee, which sought to foment international opposition to the South African apartheid regime. The ties were strengthened during the 1973 festival, as representatives of the ANC and SWAPO made their way to East Berlin after attending a Pan-African Student Congress in Tunis in mid-July. Junge Welt reported that, at the end of the Congress, over one thousand African youths had flown directly to East Berlin to attend the Red Woodstock festival.Footnote 61

Such connections conformed to the East German socialist international ideal; yet, they also produced lexicons of resistance that proved problematic for the East German state. This could be seen, for instance, in the list of demands that members of the Pan-African youth group delivered to the festival committee, including the guarantee that all countries that pursued a policy of apartheid or imperialism—with specific reference to South Africa, Rhodesia, and Israel—be banned from the festival. Directly challenging East German authorities, the Pan-African youths further threatened to boycott the events—especially if Chinese communist youths were not allowed to participate. East German authorities assured them that representatives of “racist regimes” would not be in attendance; yet, they obfuscated on the latter demand, noting that it was up to the Chinese to decide whether they would participate.Footnote 62 The boycott was averted, but such groups succeeded in highlighting their alternative solidarity agendas within the very same public spaces where the 1973 festival events took place. In the following years, the GDR would maintain ties to Pan-African youths, as well as to the ANC and SWAPO movements, as part of its broader solidarity agenda, largely by providing material aid and instituting solidarity campaigns for their causes. To some extent, the groups’ international and, at times, revolutionary ideals would thus remain embedded in the East German solidarity agenda well after the Red Woodstock had ended.

Socialist Ritualized Culture between the Carnivalesque and the Everyday

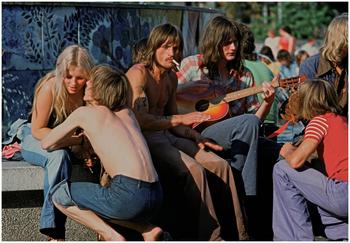

In between the staged events, Alexanderplatz assumed the role of a leisurely meeting place for young people from around the world. In casting it as such, the East German state aimed to achieve a confluence between the political and cultural elements of the festival, as well as between the official and the unofficial spheres of youth exchange. According to the Chicago Tribune’s foreign correspondent in Bonn, “The center of Berlin resembles a giant amusement park these days. Thousands of young people of all races and colors mill [through] the main [thoroughfares,] from which all traffic has been banned. Brass bands and beat groups are playing, and choirs are singing.”Footnote 63 Laying claim to the space, young people congregated around the fountains, conversing, playing music, and drinking late into the night. The East German Press Bulletin reported that “the image, offered by the bright sunshine flooding Alexanderplatz on this day, was for the old Berliners without comparison[:] tightly packed, in small and large groups discussing and gesturing together, certain freely-spoken discussions, friendliness and cheerfulness …”Footnote 64 This was not by accident, but rather by design: East German authorities recognized that the festival could only live up to their idealized images of solidarity's heterogeneity through the creation of an atmosphere that seemed somewhat conducive to open and uninhibited youth interaction.Footnote 65

Fig. 4. East German Youth at the Festival. Source: German Historical Museum Nr. 2011-155 / Photo Credit: Thomas Hoepker, Magnum Photos

To that end, the East German leadership intentionally integrated popular youth rituals into the festival program in order to appeal to young people's shared interests and desires. For instance, the festival planners transformed Alexanderplatz into an open-air stage for rock concerts, in addition to more traditional folk music. Their focus on popular youth genres reflected the fact that the SED had taken decisive measures in the previous years toward integrating youth “dance music” into the state cultural agenda, with the relaxing of sanctions against Western artists and the opening of discos throughout the GDR.Footnote 66 The state's embracing of popular music went back to the 1950s and 1960s; however, this had been a slow process involving moments of heightened repression. In December 1965, for example, the SED attempted to crack down on beat and rock music at the Eleventh Central Committee Plenum, declaring the decision necessary to curtail “American immorality and decadence.”Footnote 67 Yet, by the early 1970s, authorities had come to recognize that such measures had proven largely futile. When Erich Honecker became head of the East German leadership in 1971, the state adopted a new path, embracing youth music more openly.Footnote 68

Around this time, the FDJ began promoting East German song groups and organizing music festivals. In founding a broader Singebewegung (song movement), the FDJ established the official October [Song] Club, which was created out of the informal, Berlin-based Hootenanny Club of young musicians. Beginning in the 1970s, East Germany also began hosting annual, state-sponsored Political Songs festivals, inviting performers from around the world to the GDR to play music with a decidedly political bent. The FDJ, for its part, sponsored the organization of thousands of amateur groups in the GDR to write and perform political music for festivals that conformed to state-socialist ideals. As Marc-Dietrich Ohse has suggested, “The song movement represented a compromise between the needs of the East Berlin leadership for a minimum degree of cultural autonomy and the internationalization of youth culture.”Footnote 69 In other words, the movement was a site of negotiation between the authorities, who wanted to control the influence of Western music, and youths, who gravitated to it for various reasons. In 1973, the former planned to have East Germany's annual Political Songs festival coincide with the Red Woodstock, organizing performances, workshops, discussions, and open-air concerts that brought into the open the tension between the authorities’ attempt to create state-controlled music events and the participants’ desire to use music for their own purposes.

For East German authorities, music remained much less a manifestation of individualistic artistic expression than a political weapon that could be utilized to fashion a consciously socialist—as well as internationalist—citizenry. The West was seen to have taken advantage of music's ability to stir dissent among East German youths in the 1960s; in response, GDR authorities were now attempting to curb such influences, even repurposing them for their own ends. In the opening days of the festival, Junge Welt made clear, “The Song Festival is not a gala show, but rather a coming together of people, who play songs and sing about their daily struggles.”Footnote 70 East German authorities had carefully selected performers based on whose music would forward the international solidarity agenda. In total, over one hundred groups and soloists from forty-five countries were invited to participate, including Miriam Makeba from South Africa, Canzoniere Internazionale from Italy, Taoné Manguaré from Cuba, and Inti-Illimani from Chile. In addition, West German bands such as Floh de Cologne and Lokomotive Kreuzberg were featured on the program.Footnote 71 Most of the groups comprised self-proclaimed leftists, as well as representatives of international resistance movements; yet, as we will see, their music opened up both the lexicon and the performative aspects of the East German solidarity discourse, demonstrating its universality as well as its malleability.

As the authorities anticipated, the West German agitprop band Floh de Cologne drew large crowds to its performance. Floh was made up of a group of musicians who supported the West German Communist Party (DKP), which formed in the late 1960s, filling the void of the former Communist Party of Germany (KPD) outlawed in 1956. In contrast to many other beat and rock groups in the West, the group's music was overtly political. As Timothy Brown has pointed out, “Floh's performances tended to feature less ‘songs’ per se than political rants spoken or shouted over musical grooves.”Footnote 72 In its manifesto, the group declared that “we use pop music as a transfer-instrument for our political texts. We take this to be more effective than, for example, lectures.”Footnote 73 In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the band was popular among both East and West German youths; even SED leaders approved the group's music, especially since it had released an album in 1968 condemning the war in Vietnam.

An East German documentary of the 1973 World Festival captured images of Floh on stage on Alexanderplatz, comparing socialism in the GDR to capitalism in the West. The group's catchy lyrics contained a degree of irony, highlighting companies and other things forbidden by the East German state that supposedly did so little for the West German working class: “In the GDR, however, almost everything is forbidden, Deutsche Bank, Dr. Oetker, Gunter Sachs, Helmut Horten, Jacqueline Onassis, and many other things that the workers need for everyday life …,” as well as “hospital charges, rent increases, teacher shortages, accumulation of wealth in employer hands … and everything else that makes capitalism so attractive for the workers.”Footnote 74 Floh's criticism of West German capitalism through the lens of the East German's “forbidden society” was powerful, particularly because West Germans themselves, who were fed up with inequalities at home, were articulating it. But Floh's lyrics also implicitly acknowledged the forbiddenness that fueled dissent in “real existing socialism.” This double meaning was likely not lost on young East Germans, who coveted many Western goods in their everyday lives—goods that remained forbidden or unavailable in the GDR.

The West Berlin group, Lokomotive Kreuzberg, staged a similar “Politrock” (political rock) performance during the festival. Hailing from the West Berlin countercultural scene that had its roots in the district of Kreuzberg, just on the other side of the Berlin Wall, Lokomotive also used rock music as a vehicle of social criticism. At the festival, they performed the rock-and-roll theater piece “James Blond: In Pursuit of the Wage Robbers,” a parody about a secret agent disguised as a worker, who was pursuing a case of wage robbery. Junge Welt praised the group's eclectic performance for combining a number of genres, from rock-and-roll to blues and beat, coupled with provocative anticapitalist lyrics that served as a form of “political agitation” that “got under one's skin.”Footnote 75 Their inclusion in the festival program undoubtedly set the precedent for invitations to other West German political rock bands in the following years, especially after the establishment of the East German “Rock for Peace” program in the 1980s. For example, the well-known West German musician Udo Lindenberg, among others, would be invited to perform at a peace concert in the GDR in 1983; unlike the earlier performances, however, Lindenberg would generate unrest among youths and provoke the ire of the authorities by speaking out more openly against the policies of the East German state.Footnote 76

During the 1973 festival, neither Floh's nor Lokomotive's lyrics proved all that problematic for the authorities. Rather, it was the uninvited actors, such as East German dissidents, who launched a more open critique of the East German state by using the political song as a vehicle of protest against state socialism. In the months preceding the festival, East German singer and songwriter Wolf Biermann had submitted a piece to the Political Songs forum, which the authorities refused to include in the festival's program. Biermann—who was blacklisted at the time because of his overtly oppositional music—nonetheless decided to take advantage of the relaxed atmosphere on Alexanderplatz to play the song anyways. He later amusingly recollected the scene as one in which East German youths, as well as others from around the world, had created an organic space near the Weltzeituhr (World Clock) for him to perform, with the Stasi unable to break through to stop him.Footnote 77

Creating his own makeshift stage on Alexanderpaltz, Biermann played a rendition of “Comandante Che Guevara,” in which he paid homage to Che, with a red star on the breast of his jacket and a cigar resting on his lips, as an icon of revolutionary socialism.Footnote 78 By the late 1960s, Che had become an internationally recognized symbol, elevated to martyr status for the socialist cause. His name was synonymous with resistance, usually against capitalism, but occasionally, as in the case of Biermann's song, he represented a symbol of revolutionary purity that could be directed against state socialism as well. Biermann used the political song to launch a leftist critique of the East German state in the very language of international solidarity that the state was espousing. In doing so, he effectively drew on an alternative conceptualization of socialist internationalism that elevated Che as a true revolutionary—in contrast to the functionaries of the GDR. His performance resulted in not only a stretching but also open subversion of the state's anti-Western solidarity discourse through its anti-statist depiction of Che.Footnote 79

In an infamous crackdown by the East German state, Biermann was later expatriated in 1976, while performing on tour in West Germany. Scholars and activists alike have pointed to this as a turning point away from the early years of liberalization under Honecker's authority.Footnote 80 Yet, it is nonetheless important to contextualize Biermann's performance on Alexanderplatz within the East German state's broader shift toward a ritualization of the political song—one that would have lasting repercussions well beyond the events of the festival. As David Robb has suggested, political songs continued to serve as “a popular and important cultural force” that remained a youth ritual in the GDR until 1989: “the attraction for many fans lay in the singers’ exploitation of a basic contradiction within the GDR cultural policy. On one hand the political song was nurtured at an official level as a proudly coveted Erbe of revolutionary tradition. On the other hand, it was constantly viewed with suspicion due to its potential as a means of subversion.”Footnote 81 Biermann, among others, embraced solidarity in the name of socialist internationalism—just not in the way the state had intended. His political critique using the imagery of the Third World icon Che Guevara demonstrated the extent to which competing conceptions of socialist internationalism were becoming endemic to the East German solidarity project by the 1970s. This was apparent as the hundreds of thousands of youths and other visitors who descended upon East Berlin reimagined the socialist ideal, rendering it once again “grotesque” (to draw on Stallybrass and White), as they opened it up to include alternative meanings—and their own vision of international solidarity.

Performing Non-Normative Expressions of Gender and Sexuality on Alexanderplatz

Embodying the atmosphere of the original American Woodstock festival, young people also engaged in nonnormative expressions of gender and sexuality that were forged, once again, through a negotiation of the East German solidarity agenda and the competing subjectivities of the young people in attendance. To that end, gender and sexuality functioned as both sites of control by the East German state and of resistance by East German citizens and international guests. In the lead-up to the festival, the East German state had sought in various ways to limit what it deemed to be sexual “transgressions”: by removing sex workers and “subversive” youths from the festival venue, and by turning back others at its borders. At the same time, state propaganda at the festival embraced certain expressions of sexual emancipation—such as public nudism. As Josie McLellan has argued, “nudism was an important and highly visible part of the East German sexual revolution,” particularly because East Germans had won a hard-fought struggle against the SED for the right to a Freikörperkultur (“free-body culture”) over the previous decades.Footnote 82 The state's acceptance of “free-body culture” was apparent, for instance, in the July 1973 edition of the East German monthly publication, Das Magazin, which featured a cover sketch with women of diverse ethnicities swimming together naked in a pool.Footnote 83 The image reflected East Germany's increasingly emancipatory rhetoric about the female body, coupled with the state's proclaimed ideal of racial heterogeneity—while nonetheless reinforcing certain notions of women as pure and unadulterated, as they swam side-by-side in the nude. Of course, articulations of gender and sexuality would prove to be far more complex during the festival itself.

Those who attended the 1973 festival referred to the events that took place in East Berlin not only as the “Red Woodstock” but also as the “Summer of Love.” The well-known East German writer, Ulrich Plenzdorf, who attended both the 1951 and 1973 festivals in East Berlin, noted that, during the earlier festival, it had been his job to monitor the parks: “We recorded the personal details of the people, because there was naturally quite a blessing of children nine months later. I guess that also happened in 1973.”Footnote 84 Rumors of Weltfestkinder (festival children) were, in fact, common after the 1973 festival as well.Footnote 85 The festival consequently acquired a reputation for sexual encounters—encounters that occurred on the margins of its monitored and controlled public spaces.

Though aware of such encounters, East German authorities nonetheless attempted to utilize the festival to uphold the state's long-standing commitment to monogamy and heterosexuality, while simultaneously reinforcing deeper taboos concerning relationships with foreigners. The authorities even selected fifteen young couples from across the GDR to celebrate their weddings at the festival. The couples, wearing white dresses and dark suits, were paraded through the city before the international guests, reinforcing the importance of the traditional institutions of marriage and family life in the GDR.Footnote 86 The authorities’ decision to select white couples reflected the unspoken norm of privileging marriages between white citizens over interracial marriages or marriages with foreigners. Yet, in order to maintain a semblance of international solidarity, Junge Welt highlighted that Nguyen Duc Soat, a hero of the Vietnamese People's Air Force, had, “in the Vietnamese tradition, wished all the couples a long life [and] many children, and presented them with small gifts: parts from downed US aircraft.”Footnote 87

Yet, for international youths and workers living in the GDR at the time, the limits of East German solidarity, especially when it came to interracial marriages between East Germans and foreigners, were omnipresent. As Sarah Pugach has argued, “the anxiety surrounding African men who consorted with white women made it clear … that even if racial biases were denied on an official level, bigotry nonetheless endured.”Footnote 88 The same year that the festival took place, an international contract worker from Africa submitted a request to GDR authorities to bring his East German partner and their child back home with him. When the authorities denied his request, he submitted a complaint to the Free German Trade Union Federation (Freier Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund, or FDGB): “It is unthinkable for me to have to return to my homeland without marrying and bringing back my wife and child with me. I can't avoid the impression that there is considerable variation in decisions about marriages between East German citizens and citizens from developing countries which I cannot find any explanation for.”Footnote 89 Unlike the newlyweds paraded around East Berlin during the festival, such partnerships were far from a cause for celebration for authorities. Despite the state's claims to the contrary, a set of racialized matrimonial norms remained deeply embedded in East German society, leaving their mark on the various rituals that took place not only during the festival but also in everyday life.

Fig. 5. Newlyweds on the way to the Festival Club in 1973. Source: Bundesarchiv Bild 183-M0813-788 / Photo Credit: Jürgen Sindermann.

Yet, the festival's participants called into question the state's agenda through more open acts of transgression against imposed sexual norms, especially on the subject of gay rights. This was apparent when Peter Tatchell, an Australian participant in the British delegation, collaborated with a group of young people from East and West Berlin to create one of the first gay rights demonstrations in the East German capital. Tatchell had initially used the official meetings during the festival as a forum to advocate for gay rights, resulting in the authorities turning off the microphone and halting simultaneous interpretation of his speech; in the end, he nevertheless managed to deliver it.Footnote 90 The event proved to be just the first of his attempts to defy the East German authorities. Tatchell distributed thousands of leaflets in the streets—nearly resulting in his arrest—before attending the festival's final rally, where he carried a sign across Alexanderplatz that read (in German): “Gay Liberation Front—London, Civil Rights for Homosexuals,” and “Gay Liberation: Homosexuals support socialism.”Footnote 91 The sign introduced a rights discourse that did not condemn East German socialism per se (the GDR had decriminalized homosexuality in 1968, even before West Germany), so much as call into question the East German state's continued heterosexual norms.

At the time, East German gay and lesbian activists, many of whom were members of the FDJ, were in the midst of launching their own grassroots gay rights movement, which would become known as the Homosexual Interest Group Berlin (HIB). The group had developed connections with their West German counterparts, such as the Homosexual Action West Berlin, but they nonetheless saw themselves as forging a distinctly East German movement.Footnote 92 While Tatchell recalled a number of delegations expressing hostility toward the gay rights movement in general, East German activists and allies also came out in support of his demonstrations. In fact, they even carried their own banners at the final rally that read: “We homosexuals of the capital welcome the participants of the Tenth World Festival and are for socialism in the GDR.”Footnote 93

The East German state was less than accommodating when it came to the gay rights demonstrations. FDJ officials and police, as well as members of Tatchell's own delegation, made repeated attempts to stop him and others from participating in the rally, ripping up their posters and even threatening and assaulting them. East German officials had also approached Tatchell in a restaurant near Alexanderplatz just prior to the rally, asking him about his intended activities. While it is unclear exactly what transpired, Tatchell claims that, after an initial show of force, he was let go, likely because officials did not want to attract media attention. At the rally, Tatchell again faced resistance from a number of festival participants after he pulled out the gay rights poster: “Ignoring demands that we disband, more than 30 of us decided to march to Marx-Engels Platz and join the rally. We had gone barely forty yards along the road when we were set upon violently by some of the anti-gay members of the British delegation who had apparently decide to stay behind and keep an eye on us. Fighting them off, we regrouped and marched onwards through Alexanderplatz with the fragment of placard held high.”Footnote 94 In the end, East German youths—both from the HIB and the FDJ—helped Tatchell escape to the rooftop of an apartment building nearby, where they regrouped to watch the fireworks marking the end of the festival.Footnote 95 According to Tatchell's account, he received letters after the festival from sympathizers—including some from as far away as the Long Kesh (Maze) detention center in North Ireland and the ANC of South Africa—who had heard about the gay rights protest.Footnote 96

The gay rights demonstration on Alexanderplatz should not be read as a unique moment of “authenticity,” in contrast to the “inauthentic assemblage” of East German and international youths. Nor did it embody a slippage into the unofficial sphere of individual transgressions in the midst of the East German state's official activities. Rather, it represented one of the many articulations of international solidarity that emerged during the festival, though, in this case, one that delineated the borders of an alternative imagined community. In the aftermath of the festival, the gay rights movements on either side of the Berlin Wall would remain interconnected, continuing to forge ties in their struggle to transform the heterosexual norms of both German states, though in different ways.Footnote 97 The demonstration's significance should thus be contextualized not as a fleeting moment of youth defiance indicative of the festival's “upside-down” character, but rather as part of an ongoing fragmented conversation on gay rights that had significance at both the local and global levels.

Conclusion

The modern festival, like Bakhtin's carnival, offered a space of competing imaginaries that exemplified, rather than subverted, the realities of everyday socialist society. This was partially the case because the festival rituals reflected, while never quite fully conforming to, state-socialist ideals. More important, however, the East German state's embrace of socialist internationalism gave expression to competing subjectivities through the heterogeneity of those who participated in the various solidarity activities. The state's commitment to international socialist solidarity thereby came to exemplify the Bakhtinian “grotesque body” that it could never quite purge from its midst. In this respect, the Red Woodstock festival reinforced a lexicon of resistance within East German public spaces that was internationalist, anti-imperialist, and even revolutionary in its articulation, representing one of the many inherent paradoxes of the East German socialist project.

More generally, the musical performances, late-night discussions, and anti-imperialist expressions of solidarity that the state interwove into the rituals established during the 1973 festival, and even earlier, did not disappear from East German society after the festival's end. Instead, they were ever present in the state's attempt to fuse the state solidarity agenda with various international youth cultural trends during the late socialist period. In turn, young people from the GDR and beyond transformed the East German capital, through the subtle appropriation, transformation, and even outright subversion of the state-generated discourse on international solidarity, in ways that would, time and again, upend East German norms during the late socialist period.Footnote 98