The Berlin Wall and the borders of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) have always carried an immense symbolic weight and loomed large in late twentieth-century European history. Not only have images of East Germany's borders come to serve as a visual shorthand for the global fault line between the capitalist and socialist systems, but “the world's most conspicuous border” has also been used to define the four decades of Socialist Unity Party (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, or SED) rule. The opening of the Berlin Wall was a “global iconic event”—synonymous with the end of not only the GDR and the Eastern bloc, but the Cold War writ large.Footnote 1 Never has a single state been so identified with its border. Yet the focus of both grand narratives and public memorializations and commemorations associated with the GDR's border regime and those killed by its lethal policies overshadows the mobility and normalcy that coexisted with deadly force. Beyond the 140 killed at the Berlin Wall and the—as of yet—untold more at other border sites,Footnote 2 millions also crossed this boundary to visit family, conduct international business, visit tourist sites, and transit without major incident on foot or by car, truck, train, or airplane.Footnote 3 Although the opening of the Berlin Wall has been heralded for inaugurating an era of globalization in the 1990s that continues to this day, the borders of the GDR were already sites of transnational and global interconnection well before the mass demonstrations of 1989 brought an end to both the border regime and SED rule—if not yet the GDR as a state.Footnote 4

This special issue seeks to understand the practices that created the many borders of the GDR—most obviously those that formed the state itself,but also others, some formed by its neighbors, others by global institutions—as elements in interconnected and overlapping regimes of mobility. The articles in this special issue position the borders of the GDR within a broader history of bordering in Germany and Europe and serve as an example that continues to be relevant today, even in the supposedly globalized and borderless Europe of the Schengen Area. The five authors contributing to the special issue examine East German border practices and the making of the GDR border beyond the binaries of open versus closed, state policy versus popular agency, and transnational flows versus national boundaries.Footnote 5 In a dictatorship as fixated on securing its outer frontier as the GDR, the realities of border control were generated by a multitude of actors: party leaders creating policy; Stasi, border and customs agents implementing that policy; and state bureaucrats and experts situating East Germany in an increasingly complex world of international law and globalizing commercial trade. The GDR's border practices were also shaped from below by the wide range of people who crossed East German boundaries—with or without the permission of the state—including migrants, workers, fishermen, drug smugglers, and globe-trotting scientists (all of whom appear in this special issue). In addition, they were also shaped by nonhuman mobility, including television and radio signals, and nature itself: the waterways and the fish that traveled within them; the air and the pollution it carried; and, of course, those great transnational actors—pests and infectious disease.Footnote 6

The history of the bordering of the GDR and the violence inflicted at its frontiers also must be examined beyond the isolated chronology of the Cold War. The problem of defining and policing frontiers and controlling mobility across the borders of German states is centuries, not decades, old.Footnote 7 Similarly, institutions of border control did not form in a vacuum, but built upon organizations that long predated state socialism.Footnote 8 Furthermore, the conflicts between the GDR and the People's Republic of Poland (to take but one example) were embedded in a longer history of the German-Polish borderlands and struggles over language, identity, and nationality—even if the two states were now ideological allies.Footnote 9 The pressure exerted on the SED by Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) to impose West German migration standards on its own borders echoes the externalization of border controls to third countries by Western countries both historically and today.Footnote 10

Borders are enforced by people who do border work—not just the border guards with guns who dominate public memory, but also customs agents, health officials, train conductors, coast guard officers, and airline employees. The historian Alf Lüdtke has argued that although such actors were part of a machinery of state violence, they were also workers who were not only subject to power but also agents of power.Footnote 11 In line with this duality, analyses of the people who crossed the border has also moved away from a binary of outright defiance and violent repression to the inclusion of smaller acts of self-will (Eigensinn). For Frank Wolff, individual East Germans who expressed their self-will by seeking to emigrate exploded what began as “hairline cracks” in the border regime into a full-blown emigration movement.Footnote 12 Of course, cross-border exchange and the state's capacity for repression could be mutually reinforcing. As Détente opened up the GDR diplomatically and commercially and traffic between the two Germanys intensified after the 1972 Basic Treaty, the Ministry for State Security also ballooned in size to prevent the destabilization of domestic political control.Footnote 13

The initial wave of scholarship after reunification on the East German border analyzed it through the lens of Aufarbeitung—a historical-pedagogical approach aimed at elucidating the crimes of the SED as a dictatorship, as part of a social and political as well as a legal process of transitional justice. The main focus for this Aufarbeitung of the border was the study of the Grenzregime (border regimes): How was the border militarized, how was movement controlled, how was violence deployed by state agents? In the 1990s, such historiographical [?]efforts proliferated with the opening of the SED archives, the two official Enquete Commissions on East German history, and the trials of former SED officials and border guards.Footnote 14 As part of a wider portrayal of the GDR as a totalitarian state, this literature used the Berlin Wall, other forms of militarized border control, and the human rights abuses committed against those seeking to cross GDR boundaries as emblematic of the overarching power exercised by the SED and evidence of the immoral character of state socialist rule.Footnote 15 As historian Stefan Wolle put it, “The GDR was not a state with a border, but a border with a state.”Footnote 16

This view of the GDR as an Unrechtsstaat—a fundamentally unjust and illegitimate state—based on the evidence of the border regime, extended from scholarly historical analysis to the depiction of East Germany by the courts after reunification. As Christiane Wilke has argued, in courts, “The Berlin Wall stood accused not as a border, but as a symbol of a state that was understood to illegitimately divide a nation.”Footnote 17 Since the 1990s, this has been the dominant approach of publicly funded scholarship on the GDR and the work of memorial agencies in Germany such as the Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED Diktatur and the Stasi Records Archive (formerly the BStU, now the Stasi-Unterlagen-Archiv). The border relied on violence, and multiple major research projects have sought to establish precise information about those who were killed at the border, or died as a result of its existence, as well as more accurate data about family separations, prisoner exchanges, and features of the border that could offer a greater understanding of the depth of the coercive power wielded by the SED.Footnote 18

This history of violence at the border offers its own puzzles, such as the paradox that as the border became more physically imposing, it also became less deadly. Only 16 of the 140 victims of the Berlin Wall died in its last decade.Footnote 19 It might be tempting to take this fact as proof that walls are effective deterrents, given that fewer people risked crossing the more permanent structure. Instead, it is far more accurate to recognize that the physical structure was always only one component of the border and that the nature of border violence changed over time. Far more people filed petitions to emigrate in the 1980s, risking state persecution and prosecution to do so. For these petitioners, the violence of the border now came from the SED's arbitrary decisions about their futures.Footnote 20

Within the historiography of the GDR, the next generation of scholars in the late 1990s offered new approaches that questioned the complete domination of the SED, broadened understandings of state power and its limits, and interrogated how these structures were mutually constitutive with the East German border regime.Footnote 21 This second wave of GDR border history argued that the German-German border was not simply a one-dimensional manifestation of the Iron Curtain, but a co-creation of East Germany and its neighbors. It also underlined the productive nature of borders, their multiplicity, the local contexts that shaped them, and the specific actors that created them.Footnote 22 These local iterations were not established solely from “above,” but also came from "below"—albeit asymmetrically—from individuals and communities who lived in the borderlands, sought to use the border or directly policed it, as the violence of division and separation also created points of commonality across the frontier through the shared experience of the border regime as an element of daily life.Footnote 23 As Lyn Marven has said about Berlin, “The border is a scar, a reminder of a wound that in fact knits the city together.”Footnote 24 Or, as Yuliya Komska has argued, “The Iron Curtain did not exist.” In other words, instead of a single immovable ideological project, the border regime existed in many localized iterations.Footnote 25

Although the GDR's history was largely defined by its simultaneous separation and interconnection—Abgrenzung und Verflechtung—with West Germany, its land border(s) with Poland and Czechoslovakia and water border(s) with Denmark and Sweden each had their own temporalities that did not necessarily correspond to those of the German-German border.Footnote 26 The GDR understood its borders with the Scandinavian countries as a possible route out of international isolation, and Sweden and Denmark both took a pragmatic and flexible approach to relations with their socialist neighbor, resisting pressure from West Germany to conform ideologically.Footnote 27 Conversely, the GDR's border regime with allied states was often fraught: Polish authorities feared the return of German postwar expellees, while the rise of Solidarity (Solidarność) meant that the GDR's eastern border was as much of a political bulwark as its western frontier.Footnote 28 Polish and Czechoslovakian tourists and cross-border shoppers were popular figures of disdain in East Germany, used as scapegoats for shortages in shops near the border due to “smuggling and speculation.”Footnote 29

The processes of creating and policing these individual borders were entangled with each other as agreements with fraternal socialist countries in the East could set uncomfortable precedents for conflicts over the border with West Germany. Certain cross-border points of conflict, such as pollution and fisheries, aggravated relations on all sides of the GDR.Footnote 30 Others, such as narcotics trafficking and migration, began as Cold War conflicts with West Germany, but evolved to become sites of cooperation as solidarity with the Global South eroded, and SED elites reoriented themselves diplomatically toward the West. Cross-border public health and safety became vehicles for East-West collaboration in efforts to tackle shared technocratic problems as fellow countries from the Global North. Exploring these entanglements is one of the main goals of this special issue. As Andrew Tompkins has argued, “By examining different borders together, we can see … how the borrowing and reuse of symbols, plans and monuments has led to unintended convergences even in the most violently contested regions.”Footnote 31

As territorialized national control began to fall apart globally in the 1970s,Footnote 32 the SED only increased its efforts to secure the fixed, internationally recognized national borders it had finally gained diplomatically through the Helsinki Accords in 1975.Footnote 33 The SED actively pursued international trade, tourism, and exchange, wherein the border became a site for projecting sovereignty claims—a global calling card just as important as East German development aid or participation in international organizations. Transnationally networked groups, ranging from Christians to human rights activists, approached the border as an obstacle to be overcome in order to maintain ties to broader communities—both institutional and through informal networks.Footnote 34 Contract workers, refugees, foreign students,Footnote 35 and participants in the Leipzig Trade FairFootnote 36 or the World Festivals of Youth and StudentsFootnote 37 all experienced and negotiated the border as they traveled to and from the GDR.Footnote 38 Foreign residents of West Germany and of West Berlin in particular also had intimate knowledge of the border; many Turkish residents of West Berlin were frequently border crossers. East German authorities were never certain if they represented “imperialist enemies” or allied working-class victims of capitalism.Footnote 39 Diplomatic recognition reinforced East German sovereignty, but brought with it embassies and foreign diplomats who could act as agents of ideological subversion, from Western capitalists to Chinese and Albanian Maoists.Footnote 40 Members of the US occupying forces and US visitors to the divided city also actively engaged with the border.Footnote 41 US military personnel took advantage of their enhanced purchasing power in East Berlin, while Shinkichi Tajiri, a US expatriate artist of Japanese descent, produced the single most comprehensive photographic record of the border as part of a body of work that criticized the US militarism he had experienced as a child in an internment camp.Footnote 42 One of the largest, most enduring group of cross-border foreigners in East Germany continued to be the occupying Red Army forces who represented not only the threat of Soviet armed intervention, but also an everyday source of trade and barter for goods from abroad.Footnote 43 The presence of Schönefeld International Airport in East Berlin made the GDR part of a global transport network, and its integration into East-West and South links meant that the GDR in effect bordered directly on places as far-flung as Canada, Singapore, and Pakistan.

Illicit cross-border activity went well beyond the crime of Republikflucht (illegal emigration) by GDR citizens and extended from local neighbors to globalized networks.Footnote 44 A number of Cuban and Vietnamese visitors to the GDR used the opportunities provided by the border—and by airport transit lounges on the way to East Berlin—to defect. Vietnamese contract workers in the GDR notoriously smuggled out mopeds and other high-end items—often via Poland—despite state efforts to contain and control their consumption.Footnote 45 East Germany also acted as a haven for spies and as a staging point for international freedom fighters and terrorist groups.Footnote 46

Over the past thirty years, the Berlin Wall has retained its remarkable ability to serve as a reference point that obscures the rest of the border regime. The wall has held this symbolic position from the moment it was constructed to the present day, utterly dominating our collective ability to think about divided Germany. To give just one example, in the 1960s, a West German organization ran two competitions for West German children to depict German division. Although the images submitted to the first competition in 1961 were remarkably diverse, the images submitted to the second competition in 1967 focused almost exclusively on the Berlin Wall.Footnote 47 Border tourism and Berlin Wall tourism enabled West German and international visitors to “enact their perceived freedom as defined against the ‘imprisoned’ communist East.”Footnote 48 Since 1989, the fall of the wall has gradually become a “joyful historical memory”; its reconstructed remains a must-see for contemporary tourists seeking freedom in reunified Berlin.Footnote 49 Although the wall was initially treated like a resource, sold off in chunks to museums around the world, the Berlin Senate developed a “master plan” for memorialization between 2004 and 2006 in order to establish its own narrative and preempt competition from memory entrepreneurs,Footnote 50 such as the privately owned Checkpoint Charlie Museum.Footnote 51 This process “had a multiplier effect on Wall-related activities and even the establishment of other Wall-related sites,” leading to the creation of public history sites beyond the primary memorial at Bernauer Strasse, including an exhibit about the “ghost train stations” in Nordbahnhof, the East Side Gallery, and the Marienfelde Refugee Center Museum.Footnote 52

The focus on the wall produces a foreshortened memory of the border that skews our understanding thereof. First, the Berlin experience is misleadingly taken as relevant for the entire border regime—a point that has been made particularly well by scholars who have unpacked the quotidian operations of the border in rural East Germany—and disregards the borders with Poland and Czechoslovakia.Footnote 53 Second, public history has tended to memorialize the border in ways that reflect the Western rather than Eastern experiences of it . The “Berlin Wall Trail” traces the path of the western extremity of the wall, and not the place where it began for people in East Berlin, namely the multiple layers of fortifications that expanded in size and depth over the decades, or the elaborate control zones erected at border-crossing checkpoints.Footnote 54 The memorialization of the Berlin Wall and its victims has led to an emphasis on the lethal aspects of the border regime to the exclusion of its more banal functions—“anti-climbing features, roadblocks, lanes through which to control traffic, patrol paths, and informants reporting people for using words like ‘the Wall.’”Footnote 55 The East German border regime was also deployed in pursuit of goals that were common to other states—indeed, frequently in cooperation with those other states, or as Paul Steege has commented, “Westerners, too, made the Wall and its violence normal.”Footnote 56 Westerners sometimes even used the violence of the border regime for their own purposes: West Germany worked with GDR border officials to prevent unauthorized migration, whereas the United States did so in an attempt to prevent drug smuggling. These examples of border cooperation were not always as wedded to the physical structure of the border, but they nonetheless remain part of the border regime's history.

Since 2000, more than ten thousand kilometers of border wall have been constructed across the globe, and critical border scholars increasingly describe twenty-first-century border regimes in terms that apply equally well to many aspects of the East German border regime. Several even reference the Berlin Wall in passing as they seek to understand the trend toward border militarization. Wendy Brown has argued that the Berlin Wall presaged contemporary border walls by creating a siege mentality.Footnote 57 Conversely, Reece Jones has argued that the Berlin Wall created a stigma against building border walls that lasted for only a decade before walls came back into fashion after September 11, 2001.Footnote 58 “Just as the Berlin Wall represented the overreach and then collapse of the communist state,” Jones speculates as to whether the contemporary proliferation of border fencing represents a similar overreach of “the global system of place-based inequality” that anchors the current international order.Footnote 59 Other scholars have described structures of border enforcement that have totalizing aspirations. David Scott Fitzgerald argues that democracies have now begun to develop an “architecture of repulsion” out of a “medieval landscape of domes, buffers, moats, cages, and barbicans.”Footnote 60 Alison Mountz's ethnography of the Canadian border police even argues for a form of “transnational panopticism” that encourages travelers “to practice self-regulation more effectively than the nation-state can monitor them.”Footnote 61 Several scholars have also charted the development of a practice of “anticipatory border enforcement,” which seeks to identify would-be border crossers while they are still far from the border.Footnote 62 Although these scholars largely do not consult the specialist literature on East Germany, their descriptions of contemporary border regimes recall the most sensationalized coverage of the ostensibly totalitarian border of the GDR.Footnote 63 What are the differences between the borders of the GDR and today's world of walls? Is it merely that illiberal border regimes sought to keep people in, whereas new liberal border regimes seek to keep people out? Or can a careful comparison help us to better understand both? Paul Steege provides a clue about how to approach this comparison when he writes that the history of the Berlin Wall can help us “to notice how the impetus to build walls makes visible an underlying tolerance for violence that both comes before[,] and lingers after a wall is built.”Footnote 64 This issue thus seeks to trace how the “tolerance for violence” implied by a border reproduces itself in different settings, and in so doing to bring the history of the East German border back into conversation with contemporary border studies and previous scholarship that examines borders and bordering along the “closed” frontier of communist Europe.Footnote 65

The East German border is an exceptional case, but also one that contains many mundane elements shared with other border regimes across space and time when one looks beyond the spectacular episodes of violence and their symbolic weight within Cold War narratives. The GDR's border can be compared to its successors as part of a unified Germany and a united Europe, as well as to modern borders across the West more generally because they share technocratic similarities in function, albeit not in terms of ideological justification. There are echoes of the early twentieth-century imposition of strict border controls in the United States, which were justified as a means to defend against “the germs of anarchy, crime, disease and degeneracy.”Footnote 66 The transnationalization and globalization of the history of the GDR border also contributes to a reevaluation of the periodization of East German and Cold War history, particularly to the perception of “failure” and the legacy of 1989. The chronology of the GDR border is usually oriented around the establishment of formal frontiers—from above and below—and the migration patterns of GDR citizens: the founding of the GDR and the establishment of the new border in 1949; the establishment of the Oder-Neisse border with Poland in 1950; the solidification of the German-German border in 1952; the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961; the transit agreements and the Basic Treaty in 1971–1972; the Helsinki Accords in 1975; the closing of the Polish border due to Solidarność in 1980; the wave of applications to exit in 1984; and finally the emigration crisis that culminated in the opening of the Berlin Wall in 1989.Footnote 67 The articles in this collection demonstrate a set of cross-border flows that follow different timelines and narratives beyond this chronology, thus complicating the established dynamics of movement on the ground by East Germans and by a wide range of transnational actors, as well as SED efforts to control, restrict, and arrest them.

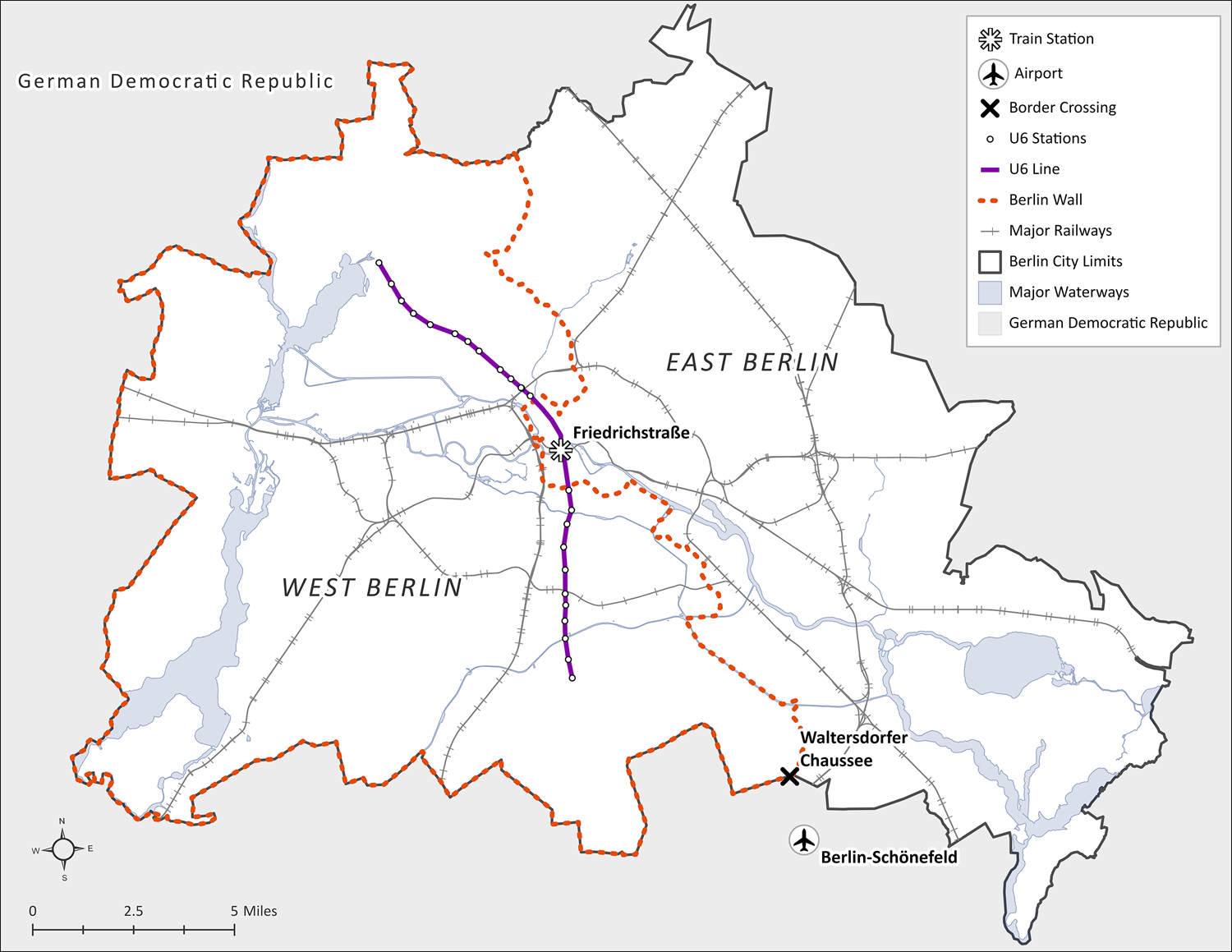

As Andrew Tompkins shows in “Caught in the Net: Fish, Ships, and Oil in the GDR-Poland Territorial Waters Dispute, 1949–1989,” the border settlement with Poland was complicated by ongoing conflicts over the exact location of the border in the waters between the two countries and by those crossing the border to illicitly exploit what had until recently been German fishing grounds. In “A River Runs Through It: The Elbe, Socialist Security, and East Germany's Borders,” Julie Ault reveals how pollution moving through waterways in the 1970s required increased negotiation and collaboration between the GDR and both its eastern and western neighbors and how environmental initiatives from the western side of the border legitimized processes of economic deindustrialization after reunification. New networks of global narcotics smuggling from the Middle East and Asia transiting through GDR territory to the West prompted competition, but eventually also cooperation, between the GDR, the FRG, and the United States as Ned Richardson-Little demonstrates in “Cold War Narcotics Trafficking, the Global War on Drugs, and the East Germany's Illicit Global Transnational Entanglement.” In “Racial Profiling on the U-Bahn: Policing the Berlin Gap during the Schönefeld Airport Refugee Crisis,” Lauren Stokes shows how a surge of refugees from the Global South via East Berlin to the West due to the international flight connections offered by the Schönefeld Airport in Brandenburg created the ironic situation of West Germany demanding greater controls over migration at the GDR's border. Finally, in “‘Not Even the Highest Wall Can Stop AIDS’: Expertise and Viral Politics at the German-German Border,” Johanna Folland demonstrates how the spread of the global HIV/AIDS pandemic led to a collaboration between scientists and health officials on both sides of the wall in the years leading up to its fall.

The borders of the German Democratic Republic were both normal and aberrant, mundane and spectacular. By putting the operation and practices of these borders in transnational and global focus, this special issue seeks to reveal new aspects of East German history and, in turn, make the GDR more legible within border studies. Such an approach can help contextualize the exceptional, and thus encourage scholars to ask new questions about which elements of East Germany were part of the broadly emerging normalcy of globalized border regimes, and which were unique to the GDR under SED rule. Despite its collapse more than thirty years ago, the GDR border regime remains ever relevant to the present: the flashpoints revealed in these articles—natural resources, pollution, narcotics, migration, and disease—have endured and become part of the long legacy of unification, not only in Germany and central Europe, but also, embedded in the meaning of borders in the post–Cold War world, across the globe.

Map 1. The German Democratic Republic by Méch E. Frazier, Geospatial Specialist, Northwestern University Libraries

Map 2. Divided Berlin by Méch E. Frazier, Geospatial Specialist, Northwestern University Libraries

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Adam Seipp and Jason Johnson for their helpful commentary on the panel that was the first draft of this special issue and the anonymous reviewers for their excellent suggestions. We also would like to thank the VolkswagenStiftung for financing a development workshop, and Iris Schröder, Christiane Kuller, and Patrice Poutrus for their incisive feedback.