Introduction

Common arterial trunk, or “truncus arteriosus,” is generally not seen concomitantly with pulmonary atresia, which, to the best of our knowledge, has thus been previously reported on but one occasion. Reference Schofield and Anderson1 We have now found two similar cases in our archive, which are reported here. Common arterial trunk is one form of single outlet from the heart and is usually found with usual atrial arrangement and concordant atrioventricular connections, although all possible segmental combinations must be anticipated to exist. Throughout the years, there has been much discussion concerning the categorisation of its variants, particularly when the lesion was usually described as “truncus arteriosus.” It could be argued that the hearts we are describing here would qualify for categorisation of the “Type 4” variants in the classification of Collett and Edwards. Reference Collett and Edwards2 In that particular lesion, however, the arterial supply to the lungs is via systemic-to-pulmonary collateral arteries, with absence of the intrapericardial pulmonary arteries. Such lesions are better described as solitary arterial trunks, since in the absence of intrapericardial arteries, there is no way of knowing, had they been formed, whether they would have originated from the heart or from the trunk itself. Reference Thiene, Bortolotti, Gallucci, Terribile and Pellegrino3 Our cases serve to validate the notion that an atretic pulmonary component can, indeed, arise intrapericardially from the major trunk, showing it truly to have initially been a common entity. In one of our cases, an arterial duct supplied the right and left pulmonary arteries, but in the other, we were unable to identify either an arterial duct or systemic-to-pulmonary collateral arteries.

Case reports

Heart 1

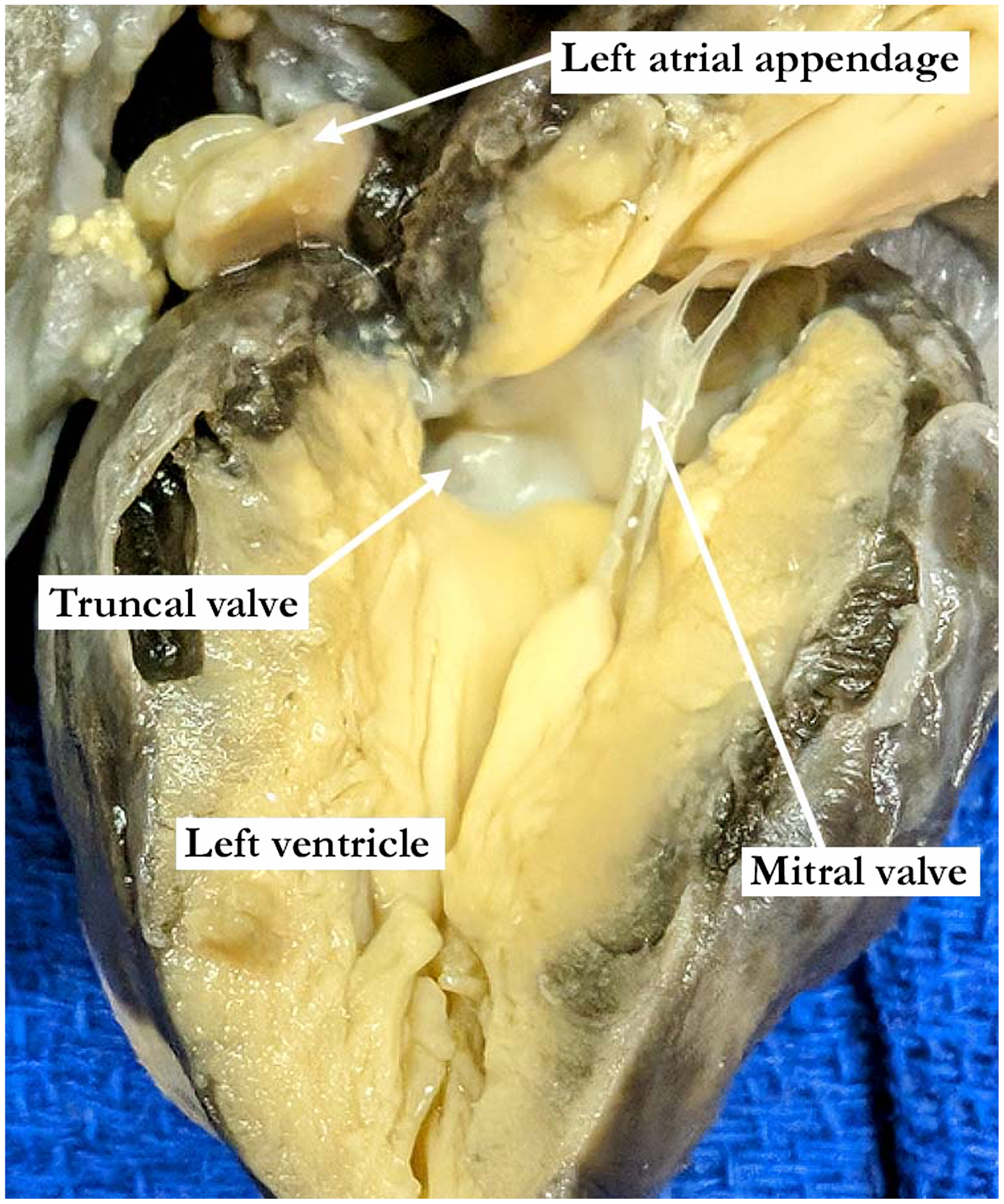

The heart was from a neonate who had no extracardiac malformations. Externally, a large arterial trunk was found supplying the systemic circulation. A thread-like fibrous structure was found arising from the left posterolateral aspect of the common arterial trunk, which gave rise to extremely hypoplastic right and left pulmonary arteries (Figure 1 left panel). There was usual atrial arrangement and concordant atrioventricular connections, with right-handed ventricular topology. The flap valve at the floor of the oval fossa was well-formed and the foramen was probe patent. The coronary sinus drained in usual fashion into the right atrium. The septomarginal trabeculation and its cranial and caudal limbs were identified, reinforcing the inferior margin of a juxta-arterial interventricular communication that had a muscular postero-inferior rim. The arterial trunk was supported mostly above the right ventricle (Figure 2). Its orifice was guarded by a three-leaflet valve, which was in continuity with the truncal leaflet of the mitral valve. A single coronary artery was seen arising from the left sinus of the truncal root. Also, within the left sinus of the truncal valve and separate from the coronary orifice was a small dimple (Figure 1 right panel). This dimple matched the origin externally of the atretic pulmonary component of the intrapericardial arterial tree (Figure 1). Neither an arterial duct nor ligament could be identified, and there were no systemic-to-pulmonary collateral arteries. The aortic component of the common trunk branched normally to supply the brachiocephalic arteries and continued as an unobstructed left arch.

Figure 1. The left panel shows the outer aspect of the common arterial trunk with the atretic pulmonary trunk (yellow arrow) arising from the left posterolateral aspect and branching into the hypoplastic right and left pulmonary arteries. In the right panel the common arterial trunk arises predominantly above the right ventricle with a juxta-arterial interventricular communication opening between the limbs of the septomarginal trabeculation (black Y). The single coronary orifice and the dimple are within the same valvar sinus. The dimple was immediately adjacent to the atretic pulmonary trunk on the outer aspect of the common arterial trunk.

Figure 2. The left ventricular view demonstrates the mitral to truncal valve fibrous continuity and the greater commitment of the common arterial trunk to the right ventricle.

Heart 2

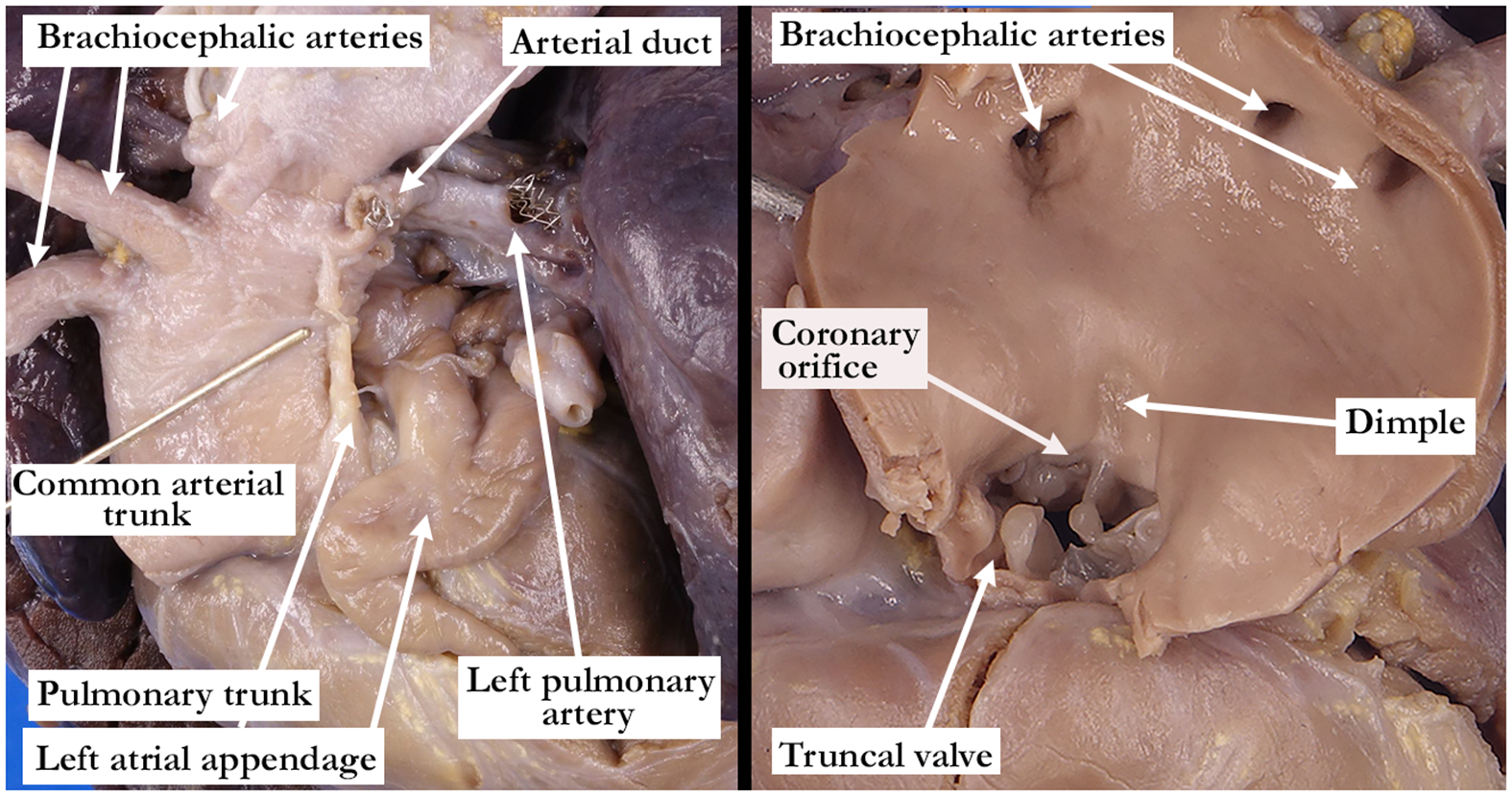

As in the first heart, a large arterial trunk arose from the base of the ventricular mass to supply the systemic circulation. A fibrous pulmonary segment arose intrapericardially from the left posterolateral aspect of the trunk, giving rise to confluent but hypoplastic right and left pulmonary arteries. An arterial duct was present, with a stent placed in it to the left pulmonary artery (Figure 3 left panel).

Figure 3. The left panel shows the outer aspect of the common arterial trunk with the atretic pulmonary trunk arising from the left posterolateral aspect. This atretic structure was cut during dissection, but could easily be approximated with the distal atretic component that gave rise to the right and left pulmonary arteries, which were supplied via an arterial duct. The right panel shows the mildly dysplastic truncal valve and the opened common arterial trunk. The dimple was noted above the sinutubular junction and above a valvar commissure. The dimple was immediately adjacent to the atretic pulmonary trunk on the outer aspect of the common arterial trunk.

There was usual atrial arrangement and concordant atrioventricular connections with right-handed ventricular topology. The flap valve at the floor of the oval fossa was well-formed and the foramen was probe patent. The enlarged coronary sinus, draining a persistent left superior caval vein, emptied in usual fashion into the right atrium. Within the right ventricle, the septomarginal trabeculation, along with its cranial and caudal limbs, formed the floor of a juxta-arterial interventricular communication, which had a muscular postero-inferior rim. The arterial trunk arose from the ventricles in balanced fashion (Figure 4). Its orifice was guarded by a four-leaflet, mildly dysplastic valve. A single coronary artery arose from the left posterior sinus of the truncal root. Just above the sinutubular junction and the commissure between the left posterior valvar sinus supporting the coronary artery and its adjacent right sinus, a dimple could be seen within the wall of the arterial trunk (Figure 3 right panel). Again, as in the first heart, the dimple matched the external origin of the thread-like pulmonary intrapericardial component (Figure 3). Systemic-to-pulmonary collateral arteries were not identified. The widely patent aortic arch extended leftwards beyond the origins of the brachiocephalic arteries.

Figure 4. The common arterial trunk arises in a roughly balanced fashion above the juxta-arterial interventricular communication. The defect extends between the limbs of the septomarginal trabeculation (black ‘Y’) with the caudal limb reaching the inner heart curvature forming a muscular bar along the postero-inferior aspect of the defect.

Discussion

A common arterial trunk is defined as a vessel exiting the heart through a common ventriculo-arterial junction and supplying the systemic, pulmonary, and coronary circulations. Reference Collett and Edwards2,Reference Jacobs, Franklin and Beland4

Most frequently, all the circulations are patent. In our cases, however, the intrapericardial component of the pulmonary circulation had no patent orifice, but its atretic component could be identified as having taken origin from the arterial trunk. The possibility that hearts could exist with the combination of a common arterial trunk and pulmonary atresia was first hypothesised by Thiene and colleagues. Reference Thiene, Bortolotti, Gallucci, Terribile and Pellegrino3 The combination is important when considering the arrangement in which there is a solitary intrapericardial arterial trunk, but with the pulmonary arterial supply derived exclusively from systemic-to-pulmonary collateral arteries. Collet and Edwards had included such lesions as their “Type 4” when proposing their classification for “persistent truncus arteriosus.” Reference Collett and Edwards2 As Theine and colleagues pointed out, however, in absence of the intrapericardial pulmonary arteries, there is no way of knowing, had they existed, whether they would have taken origin from the heart itself (Figure 5), rather than from the arterial trunk. And it is the case that such hearts, in terms of clinical presentation, have much more in common with tetralogy and pulmonary atresia, rather than common arterial trunk. As far as we are aware, only one case of common trunk with pulmonary atresia had previously been reported. We now add an additional two cases to the literature.

Figure 5. In this anterolateral view of the arterial trunks, the atretic pulmonary trunk is easily appreciated anterior and leftward of the large aorta. Note how the thread-like pulmonary trunk arises from the ventricular mass. This case also had a subaortic, outlet ventricular septal defect, which is not seen in this image.

As with all cases of common trunk, the ventriculo-arterial junction is guarded by a common valve, which can have between 2 and 4 leaflets. The leaflets themselves can be normal, or show varying degrees of dysplasia. Our cases had 3 and 4 leaflets, respectively, with mild dysplasia noted in our second case. The common truncal root typically overrides the crest of the ventricular septum, with varied commitments to the right and left ventricles. Of our cases, the first had predominant right ventricular origin but was balanced commitment in the second. We found fibrous continuity between the truncal leaflets and the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve in both cases, and both exhibited a muscular postero-inferior border of the juxta-arterial interventricular communication. The postero-inferior muscular border is protective of the conduction system. This can be of surgical significance since the septal defects in both of our cases were somewhat restrictive.

As we have emphasised, the hearts fulfilling the classification as “Type 4” in the system proposed by Collet and Edwards closely resemble, in clinical terms, those having tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia. Our cases would have similar clinical features. In anatomical terms, however, as with the case of Schofield and colleagues, the hearts are unequivocally examples of common arterial trunk. An arterial duct is not typically seen in cases with common arterial trunk unless the trunk itself shows pulmonary dominance, and the duct feeds the systemic circulation, or else there are discontinuous pulmonary arteries, with one fed through a persistent duct. It is very rare to find persistence of the duct in the setting of balanced circulations.