Most people spend the majority of each day indoors (Klepeis et al., Reference Klepeis, Nelson, Ott, Robinson, Tsang and Switzer2001), and this time most likely increased with the COVID-19 pandemic. Pandemic-related lockdowns decreased many people’s engagement in physical activity – possibly up to 30 per cent – with a simultaneous increase in sedentary behaviour (Ammar et al., Reference Ammar, Brach, Trabelsi, Chtourou, Boukhris and Masmoudi2020) as a result of the changes in their daily routines. Older adults may be particularly susceptible to reduced physical activity resulting from restricted community mobility and activities limited in aged care facilities. Being active at home may be an important opportunity to mitigate the negative consequences of reduced life space. Therefore now, and beyond the current pandemic, it is important to identify features of the indoor built environment to promote physical activity in general, and specifically for older adults who may have mobility impairments.

In 2020, older adults 60 years of age and older comprised 13 per cent of the global population (World Health Organization, 2020a). In Canada in 2018, there were more older Canadians (17%) (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2021a) than Canadian children and youth under 15 years (16%) (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2021b). As the population of older adults in Canada grows, policies and practice must enable healthy aging in place. Aging in place is about honoring connections to the social and physical environments that shape people as they grow older (World Health Organization, 2020a). Along with housing, aging in place is also facilitated by how older adults care for themselves through engagement in physical activity (Tao, Zhang, Gou, Jiang, & Qi, Reference Tao, Zhang, Gou, Jiang and Qi2021; Van Holle et al., Reference Van Holle, Van Cauwenberg, De Bourdeaudhuij, Deforche, Van de Weghe and Van Dyck2016; Yen, Michael, & Perdue, Reference Yen, Michael and Perdue2009). Furthermore, older adults often participate in physical activity at home, rather than in other locations (Chaudhury, Campo, Michael, & Mahmood, Reference Chaudhury, Campo, Michael and Mahmood2016). Physical activity can improve physical function, and reduce the risk of chronic diseases and adverse events, such as falls (World Health Organization, 2020b). In contrast, prolonged sedentary behaviour can increase the risk of chronic conditions (e.g., type-2 diabetes) and lead to poor health outcomes (World Health Organization, 2020b).

There are systematic reviews on the effect of the built environment on physical activity for various demographics, focusing on neighborhood, active transport, and outdoor environment design (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Hosking, Woodward, Witten, MacMillan and Field2017; Tcymbal et al., Reference Tcymbal, Demetriou, Kelso, Wolbring, Wunsch and Wäsche2020; Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Kerr, Conway, Saelens, Sallis and Ahn2017; Yen et al., Reference Yen, Michael and Perdue2009). Studies have frequently explored the effect of the built environment on older adults and their physical activity (Cerin, Nathan, van Cauwenberg, Barnett, & Barnett, Reference Cerin, Nathan, van Cauwenberg, Barnett and Barnett2017; Tao et al., Reference Tao, Zhang, Gou, Jiang and Qi2021; Van Holle et al., Reference Van Holle, Van Cauwenberg, Van Dyck, Deforche, Van de Weghe and De Bourdeaudhuij2014, 2016). Despite the increasing evidence base for the outdoor environment, less emphasis has been placed on the indoor physical features needed to support active living for older adults (Ahrentzen & Tural, Reference Ahrentzen and Tural2015; Annear et al., Reference Annear, Keeling, Wilkinson, Cushman, Gidlow and Hopkins2014; Ashe, Reference Ashe, Nyman, Barker, Haines, Horton, Musselwhite, Peeters, Victor and Wolff2018) even though most people spend most of the day inside.

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to synthesize available evidence across all study designs to describe features of the indoor environment and physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour for older adults 60 years of age and older. For this synthesis, we define the indoor built environment as internal space(s) in which older adults reside and engage, and adjacent spaces (e.g., backyard, porch, driveway) (Peel et al., Reference Peel, Baker, Roth, Brown, Bodner and Allman2005).

Methods

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to conduct this systematic review (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009), and registered it with PROSPERO (Registration No. CRD42018095359).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included studies using any study designs, years, and languages. The study population included older adults 60 years of age and older, or the mean age of the study sample was over 60 years of age. Studies included outcomes related to physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour of older adults. The studies also reported features of the indoor environment. We excluded studies if they focused on populations younger than 60 years, or on people with dementia and falls-related research. A “one size fits all” approach does not apply to all individuals in a population, and this is especially true for people with dementia or falls-related research. We also excluded studies focused on ambient indoor temperature, because it is not part of the built environment. We excluded studies without physical activity or sedentary behaviour outcomes.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

We searched the following databases: MEDLINE® and Embase, EBSCO Databases, PubMed, and Google Scholar (title only). We used the following headings to guide our search: population (older adults), exposure (indoor environment), outcome (physical activity or sedentary behaviour). The search strategy for MEDLINE is provided in Table 1. We conducted forward and backward citation searches for included studies. We completed our last search on December 19, 2020.

Table 1. MEDLINE search strategy

Study Selection

Two authors (FA, MA) completed title and abstract screening (Level 1) based on a priori criteria. For Level 2 screening, the full texts of all included studies were reviewed by the same two authors (Figure 1); they resolved discrepancies through discussion and consensus.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram

Data Extraction

We extracted the following information for each study: title, first author, year, location, conflicts of interest, purpose, study design, funding resources, participants, indoor and/or housing and campus features, and physical activity and sedentary behaviour outcomes. One author extracted data (F.A.), and a second author (M.A.) checked 10 per cent of entries for accuracy. The same two authors (F.A., M.A.) checked the data again during the synthesis process. We used Covidence by Veritas Health Innovation (Melbourne, Australia) to conduct this review.

Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour

Physical activity is energy expenditure produced by skeletal muscles during movement (Caspersen, Powell, & Christenson, Reference Caspersen, Powell and Christenson1985; World Health Organization, 2020b) and it includes various household activities (e.g., activities of daily living [ADLs]), sports,exercise (defined as planned and repetitive movement; e.g., swimming), and other activities (e.g., work-related) (Caspersen et al., Reference Caspersen, Powell and Christenson1985). Sedentary behaviour is defined as “any waking behaviour characterized by an energy expenditure ≤1.5 metabolic equivalents of task (METs), while in a sitting, reclining, or lying posture” (Sedentary Behaviour Research Network, 2012, p. 1). In our synthesis, we use the terms physical activity or sedentary behaviour (as defined here), or specify the type of physical activity (e.g., ADLs, exercise, walking).

Private and Collective Dwellings

We defined private dwellings (e.g., houses, apartments, town homes) as residences where older adults resided in their own or rented property with access to a private entrance (Statistics Canada, 2017b) and in a community of their choice (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.). Collective dwellings (e.g., independent living, assisted living, and retirement villages) are residences where older adults either have private or shared units, live amongst a collective of older adults, and receive a range of services from meal preparation to bathing, as required (BC Seniors Living Association, 2021; Province of British Columbia, 2021; Statistics Canada, 2017a). We define “campus” as the site or property of collective dwellings and campus features, including available resources (e.g., pools, gyms) and destinations (e.g., clubhouses, gardens, and shops).

Indoor Environments

We extracted data on features of the indoor and adjacent environments. The indoor environment was within the residential unit, whereas features of the adjacent spaces were immediately outside the residential unit (Peel et al., Reference Peel, Baker, Roth, Brown, Bodner and Allman2005). In private dwellings, residential units included the house or apartment, and adjacent spaces included indoor hallways in apartments, backyards, gardens, and front lawns (e.g., distance between the house and garbage disposal or mailbox) (Peel et al., Reference Peel, Baker, Roth, Brown, Bodner and Allman2005). For collective dwellings, there were living units, resources (e.g., indoor, and outdoor pools), destinations (e.g., clubhouses, shops) and other features (e.g., indoor hallways and outdoor paths) located on the campus.

Quality Assessment

Two authors (FA-MA) evaluated the selected studies using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers or the “QualSyst” tool (Kmet, Lee, & Cook, Reference Kmet, Lee and Cook2004), and discrepancies in scores were resolved through consensus. We did not exclude studies that were of low quality.

Synthesis of Results

Two authors (FA, MA) used qualitative synthesis methods via an inductive content analysis (Mikkonen & Kääriäinen, Reference Mikkonen, Kääriäinen, Kyngäs, Mikkonen and Kääriäinen2020) over three 1-hour sessions. After checking extracted data, indoor environment features were presented on a digital whiteboard. The two authors first independently created themes from the data, then discussed themes. Between the two meetings, each author checked the coded data and noted any discrepancies or questions to discuss at the next meeting. During the final meeting, authors confirmed the findings and created a visual representation of the synthesis (Figure 2). We present the mean and standard deviations, if available, in the tables. If this information was not available, we included other data (e.g., median, interquartile range).

Figure 2. Visual summary of the findings from the included studies. The findings represent two settings (collective and private dwellings) and three domains (campus, building, and fixtures). Campus features were only identified in the collective dwelling setting. Accessibility and safety domains are important across settings.

Results

Study Characteristics and Quality

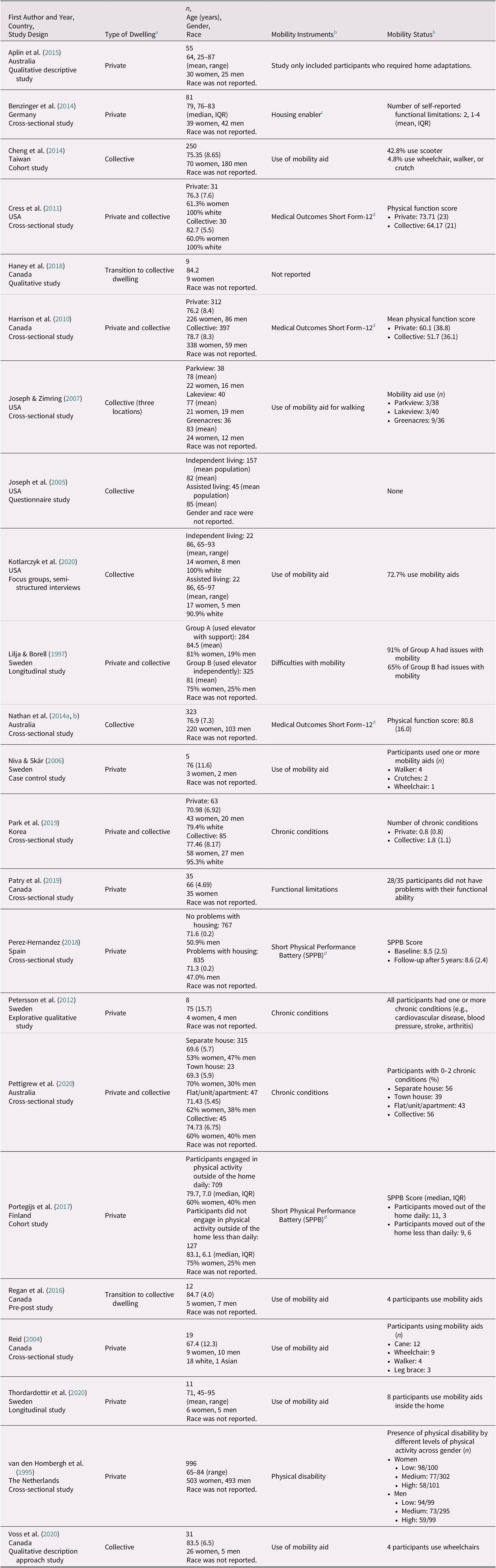

Our search strategy resulted in 1367 studies of which 23 studies were included (see Figure 1 for the PRISMA Flow Diagram) (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). We included studies with different designs (e.g., observational, pre-post) and publication dates ranged from 1995 to 2020. Studies were from the following locations: Canada (6) (Haney, Fletcher, & Robertson-Wilson, Reference Haney, Fletcher and Robertson-Wilson2018; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Fisher, Lawson, Chad, Sheppard and Reeder2010; Patry et al., Reference Patry, Vincent, Duval, Blamoutier, Briere and Boissy2019; Regan et al., Reference Regan, Intzandt, Swatridge, Myers, Roy and Middleton2016; Reid, Reference Reid2004; Voss, Pope, & Copeland, Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020); Sweden (4) (Lilja & Borell, Reference Lilja and Borell1997; Niva & Skär, Reference Niva and Skär2006; Petersson, Lilja, & Borell, Reference Petersson, Lilja and Borell2012; Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti, & Ekstam, Reference Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti and Ekstam2020); United States (4) (Cress, Orini, & Kinsler, Reference Cress, Orini and Kinsler2011; Joseph & Zimring, Reference Joseph and Zimring2007; Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin, & Kiefer, Reference Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin and Kiefer2005; Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020); Australia (3) (Aplin, de Jonge, & Gustafsson, Reference Aplin, de Jonge and Gustafsson2015; Nathan, Wood, & Giles-Corti, Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014b; Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Rai, Jongenelis, Jackson, Beck and Newton2020); Finland (1) (Portegijs, Rantakokko, Viljanen, Rantanen, & Iwarsson, Reference Portegijs, Rantakokko, Viljanen, Rantanen and Iwarsson2017); Germany (1) (Benzinger et al., Reference Benzinger, Iwarsson, Kroog, Beische, Lindemann and Klenk2014); Korea (1) (Park, Park, Hancox, Castaneda-Gameros, & Koo, Reference Park, Park, Hancox, Castaneda-Gameros and Koo2019); The Netherlands (1) (van den Hombergh, Schouten, van Staveren, van Amelsvoort, & Kok, Reference van den Hombergh, Schouten, van Staveren, van Amelsvoort and Kok1995); Spain (1) (Perez-Hernandez et al., Reference Perez-Hernandez, Lopez-Garcia, Graciani, Luis Ayuso-Mateos, Rodriguez-Artalejo and Garcia-Esquinas2018); and Taiwan (1) (Cheng, Wang, Tang, Chu, & Chen, Reference Cheng, Wang, Tang, Chu and Chen2014). The included studies were from higher income countries (The World Bank Group, n.d.). Table 2 provides study summary information.

Table 2. Study and participant information of included studies

Note. Only mean (SD) values were included unless specified.

a We stratified studies by private, collective, or transition to collective dwelling. Private dwellings are either rented or owned property in the community (Statistics Canada, 2017b; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d). Collective dwellings include units where one lives amongst a collective of other older adults who receive support services (BC Seniors Living Association, 2021; Province of British Columbia, 2021; Statistics Canada, 2017a). If the study were observing older adults when they lived in a private dwelling and after they moved to a collective dwelling, we classified it as transition to collective dwelling.

b The instruments used to evaluate mobility along with the results are included. If specific instruments were not used, we reported available data on whether participants used mobility aids and on the prevalence of chronic conditions.

c Iwarsson & Slaug, Reference Iwarsson and Slaug2001.

d McDowell and Newell, Reference McDowell and Newell1996.

e We only report data for participants who completed the Short Physical Performance Battery.

f Guralnik et al., Reference Guralnik, Simonsick, Ferrucci, Glynn, Berkman, Blazer, Scherr and Wallace1994. IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation.

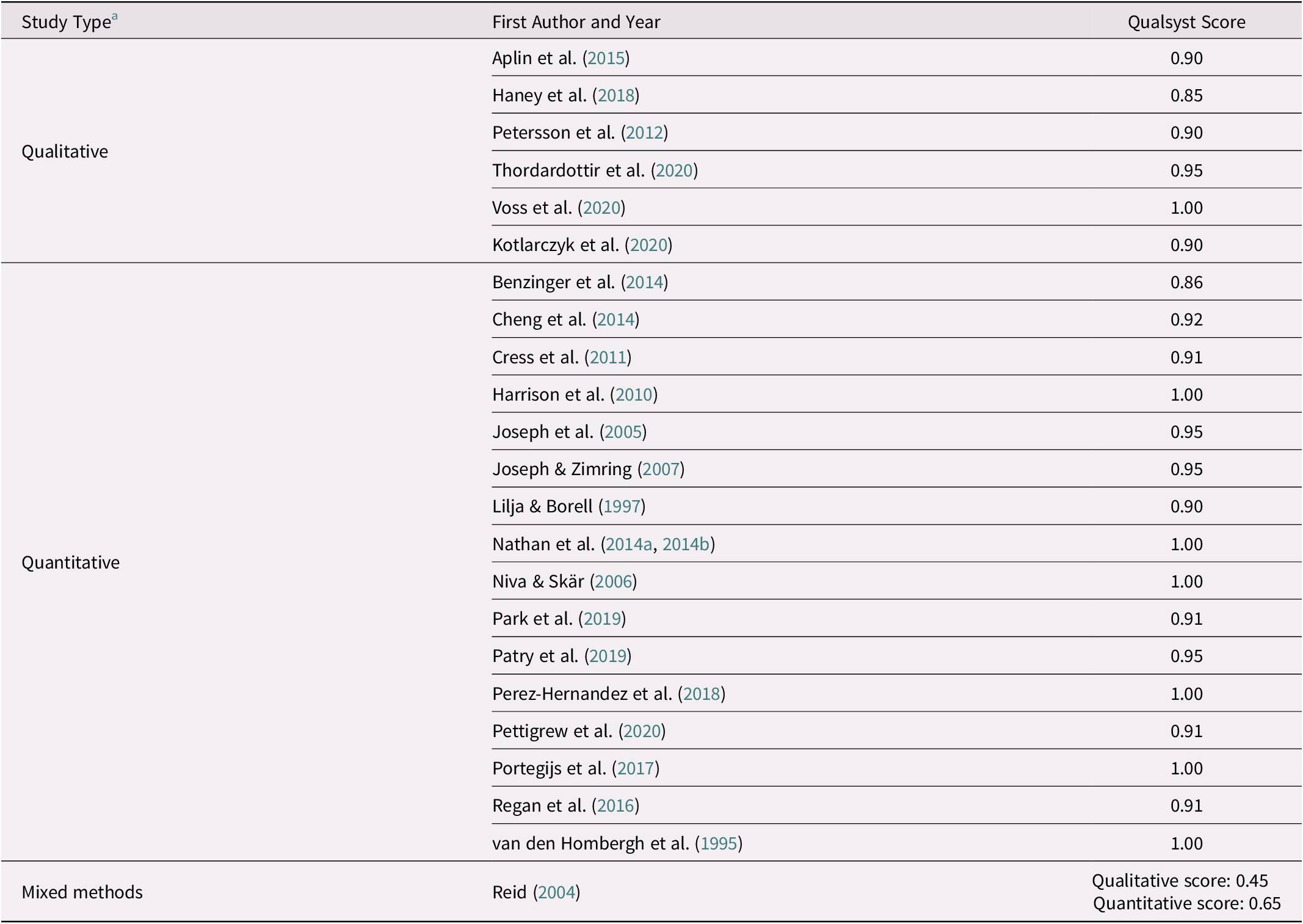

Table 3 reports the quality of included studies. For the Qualsyst tool, quality scores can range from 0.00 to 1.00. The only mixed methods study (Reid, Reference Reid2004) included in this review received the lowest scores (0.45 for qualitative and 0.65 for quantitative criteria). The remaining studies received high quality scores ranged from 0.85 to 1.00.

Table 3. Quality of included studies according to Qualsyst

Note. The Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers (Qualsyst) was used to evaluate the quality of included studies (Kmet et al., Reference Kmet, Lee and Cook2004). The minimum score is 0.00 and the maximum score is 1.00.

a Study type designates whether the study design was qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods. Qualsyst has different evaluation criteria for each study type. If the study is mixed methods, the study must be evaluated using both qualitative and quantitative criteria, resulting in two scores.

Participants

The mean group age across studies was 60 years or older. Four studies included participants below 60 years of age (Aplin et al., Reference Aplin, de Jonge and Gustafsson2015; Petersson et al., Reference Petersson, Lilja and Borell2012; Reid, Reference Reid2004; Thordardottir et al., Reference Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti and Ekstam2020). Twelve studies reported on participants’ mobility limitations (Aplin et al., Reference Aplin, de Jonge and Gustafsson2015; Joseph & Zimring, Reference Joseph and Zimring2007; Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020; Lilja & Borell, Reference Lilja and Borell1997; Niva & Skär, Reference Niva and Skär2006; Perez-Hernandez et al., Reference Perez-Hernandez, Lopez-Garcia, Graciani, Luis Ayuso-Mateos, Rodriguez-Artalejo and Garcia-Esquinas2018; Petersson et al., Reference Petersson, Lilja and Borell2012; Portegijs et al., Reference Portegijs, Rantakokko, Viljanen, Rantanen and Iwarsson2017; Reid, Reference Reid2004; Thordardottir et al., Reference Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti and Ekstam2020; van den Hombergh et al., Reference van den Hombergh, Schouten, van Staveren, van Amelsvoort and Kok1995; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020, and participants used assistive devices (e.g., walking aids and scooters) in four studies (Benzinger et al., Reference Benzinger, Iwarsson, Kroog, Beische, Lindemann and Klenk2014; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Wang, Tang, Chu and Chen2014; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014a,Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Cortib; Park et al., Reference Park, Park, Hancox, Castaneda-Gameros and Koo2019). Table 2 highlights that most studies had a study population with more women than men, but one study did not report gender (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin and Kiefer2005). Of the four studies which reported race (Cress et al., Reference Cress, Orini and Kinsler2011; Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020; Park et al., Reference Park, Park, Hancox, Castaneda-Gameros and Koo2019; Reid, Reference Reid2004), most participants self-reported as white. These studies were conducted in Canada (Reid, Reference Reid2004), Korea (Park et al., Reference Park, Park, Hancox, Castaneda-Gameros and Koo2019), and the United States (Cress et al., Reference Cress, Orini and Kinsler2011; Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020).

Housing

Ten studies observed participants in private dwellings (Aplin et al., Reference Aplin, de Jonge and Gustafsson2015; Benzinger et al., Reference Benzinger, Iwarsson, Kroog, Beische, Lindemann and Klenk2014; Niva & Skär, Reference Niva and Skär2006; Patry et al., Reference Patry, Vincent, Duval, Blamoutier, Briere and Boissy2019; Perez-Hernandez et al., Reference Perez-Hernandez, Lopez-Garcia, Graciani, Luis Ayuso-Mateos, Rodriguez-Artalejo and Garcia-Esquinas2018; Petersson et al., Reference Petersson, Lilja and Borell2012; Portegijs et al., Reference Portegijs, Rantakokko, Viljanen, Rantanen and Iwarsson2017; Reid, Reference Reid2004; Thordardottir et al., Reference Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti and Ekstam2020; van den Hombergh et al., Reference van den Hombergh, Schouten, van Staveren, van Amelsvoort and Kok1995); six observed participants in collective dwellings (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Wang, Tang, Chu and Chen2014; Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin and Kiefer2005; Joseph & Zimring, Reference Joseph and Zimring2007; Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014a, Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014b; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020); five studies compared between dwellings (Cress et al., Reference Cress, Orini and Kinsler2011; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Fisher, Lawson, Chad, Sheppard and Reeder2010; Lilja & Borell, Reference Lilja and Borell1997; Park et al., Reference Park, Park, Hancox, Castaneda-Gameros and Koo2019; Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Rai, Jongenelis, Jackson, Beck and Newton2020), while two studies observed older adults as they transitioned to a collective dwelling (Haney et al., Reference Haney, Fletcher and Robertson-Wilson2018; Regan et al., Reference Regan, Intzandt, Swatridge, Myers, Roy and Middleton2016). The age range of participants in private dwellings was from 25 to 65 years, and for people in collective dwellings it was from 65 to 97 years.

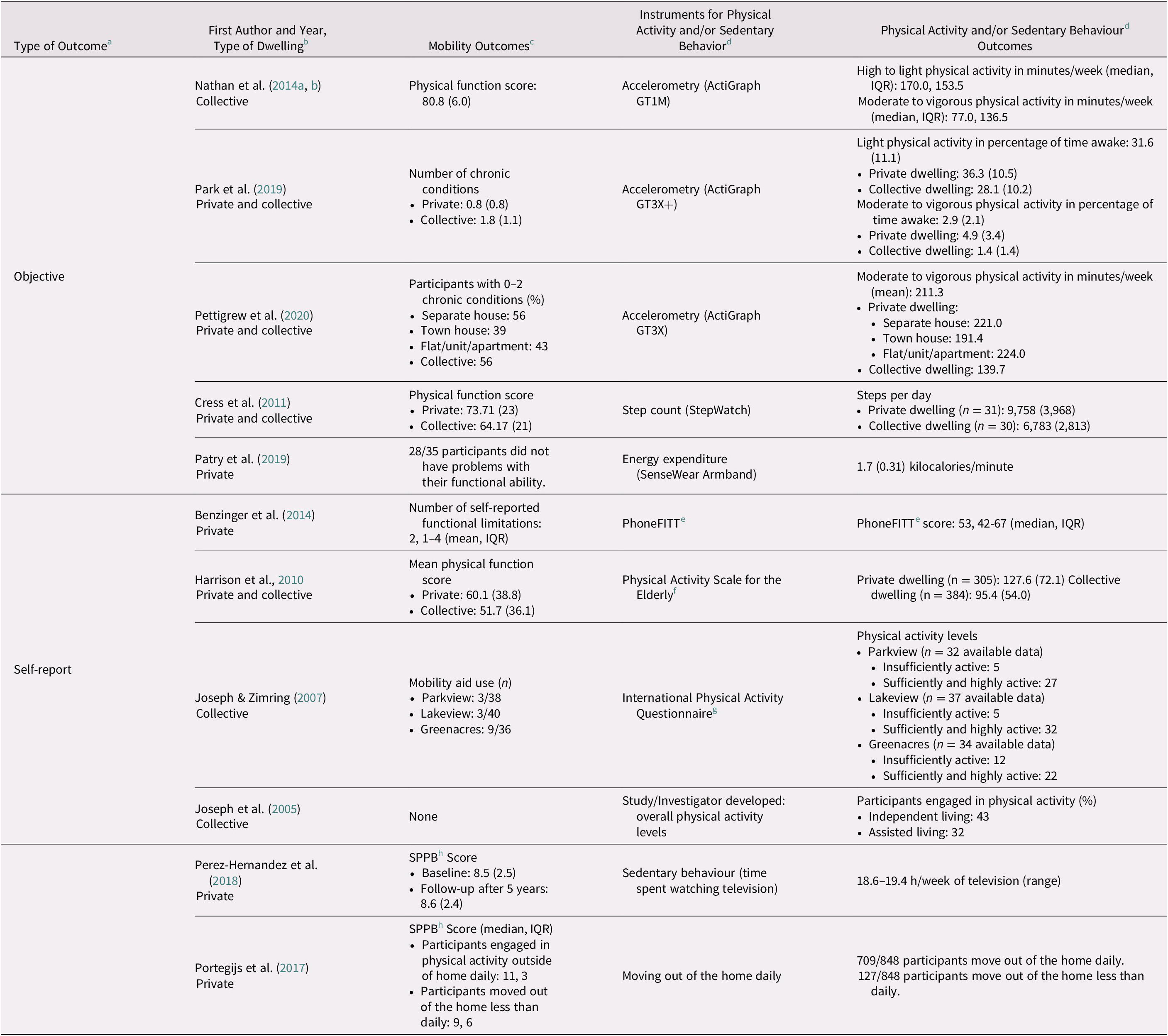

Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour

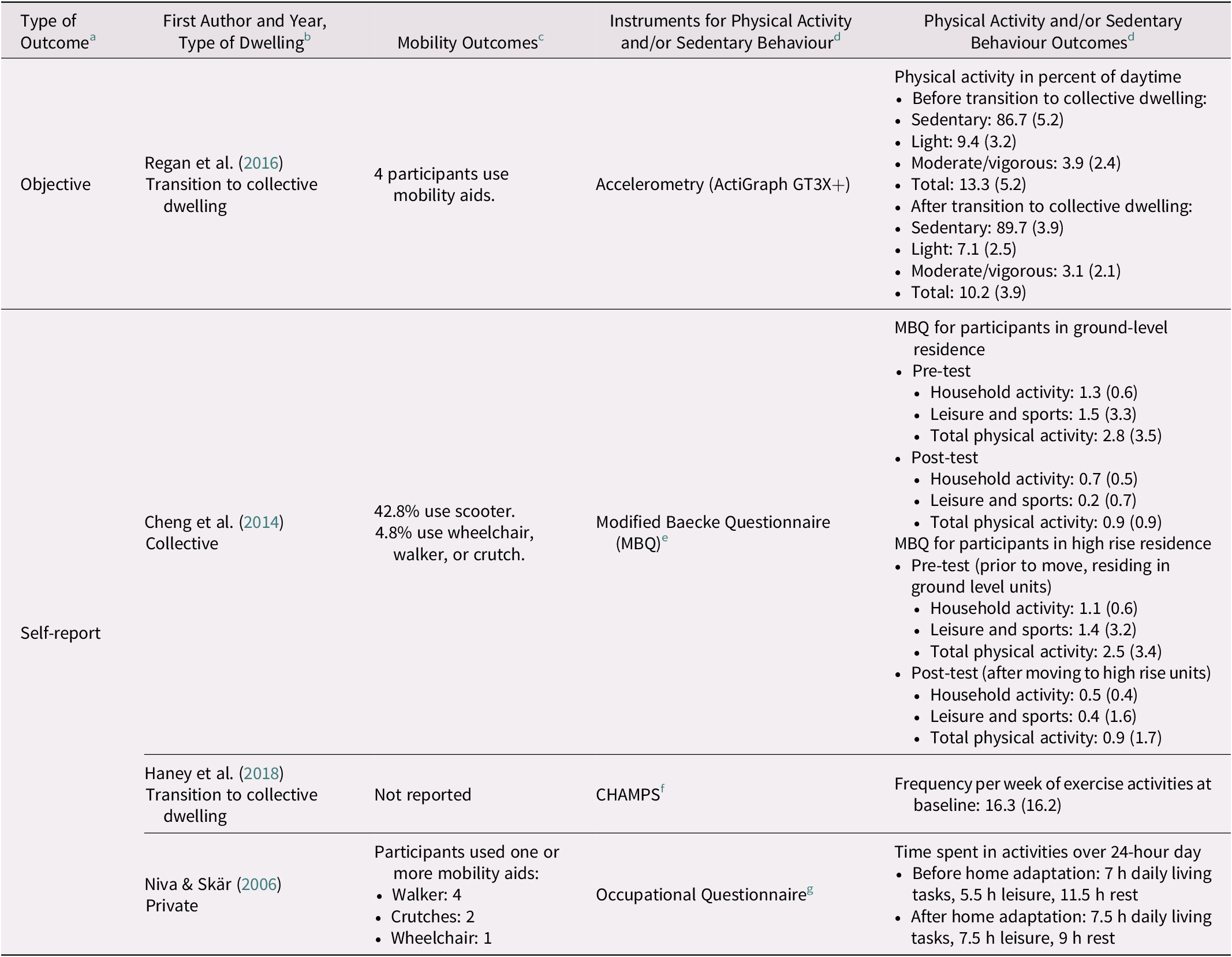

Physical activity outcomes were reported by 21 studies (Aplin et al., Reference Aplin, de Jonge and Gustafsson2015; Benzinger et al., Reference Benzinger, Iwarsson, Kroog, Beische, Lindemann and Klenk2014; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Wang, Tang, Chu and Chen2014; Cress et al., Reference Cress, Orini and Kinsler2011; Haney et al., Reference Haney, Fletcher and Robertson-Wilson2018; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Fisher, Lawson, Chad, Sheppard and Reeder2010; Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin and Kiefer2005; Joseph & Zimring, Reference Joseph and Zimring2007; Lilja & Borell, Reference Lilja and Borell1997; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014a,Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Cortib; Niva & Skär, Reference Niva and Skär2006; Park et al., Reference Park, Park, Hancox, Castaneda-Gameros and Koo2019; Patry et al., Reference Patry, Vincent, Duval, Blamoutier, Briere and Boissy2019; Perez-Hernandez et al., Reference Perez-Hernandez, Lopez-Garcia, Graciani, Luis Ayuso-Mateos, Rodriguez-Artalejo and Garcia-Esquinas2018; Petersson et al., Reference Petersson, Lilja and Borell2012; Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Rai, Jongenelis, Jackson, Beck and Newton2020; Portegijs et al., Reference Portegijs, Rantakokko, Viljanen, Rantanen and Iwarsson2017; Regan et al., Reference Regan, Intzandt, Swatridge, Myers, Roy and Middleton2016; Reid, Reference Reid2004; Thordardottir et al., Reference Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti and Ekstam2020; van den Hombergh et al., Reference van den Hombergh, Schouten, van Staveren, van Amelsvoort and Kok1995). Only three studies reported sedentary behaviour outcomes (Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020; Perez-Hernandez et al., Reference Perez-Hernandez, Lopez-Garcia, Graciani, Luis Ayuso-Mateos, Rodriguez-Artalejo and Garcia-Esquinas2018; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020); therefore, we concentrated more on physical activity outcomes. Tables 4 and 5 present information on quantitative physical activity and sedentary behaviour outcomes, including objective and self-report measures, for cross-sectional and pre-post studies.

Table 4. Quantitative outcomes of physical activity and sedentary behaviour for cross-sectional studies

Note. Only mean (SD) values were included unless specified.

a Quantitative outcomes for physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour were classified as either objective or self-report measures. Objective measures use tools (e.g., accelerometers) to report physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour, and can include accelerometry, step count, and energy expenditure. Self-report measures are when participants are asked to report their own physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour through questionnaires or surveys.

b We stratified studies by private, collective, or transition to collective dwelling. Private dwellings are either rented or owned property in the community (Statistics Canada, 2017b; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d). Collective dwellings include units where one lives amongst a collective of other older adults who receive support services (BC Seniors Living Association, 2021; Province of British Columbia, 2021; Statistics Canada, 2017a). If the study were observing older adults when they lived in a private dwelling and after they moved to a collective dwelling, we classified it as transition to collective dwelling.

c If specific mobility instruments were not used (e.g., SPPB), we reported available data on whether participants used mobility aids and on the prevalence of chronic conditions according to their study groups.

d Only quantitative physical activity and sedentary behaviour data were included. Specific instruments (e.g., CHAMPS), accelerometry, step count, energy expenditure, and study/investigator-developed outcomes were reported only. We defined “physical activity” as energy expenditure by skeletal muscles (World Health Organization, 2020b) through various types of activities (e.g., household tasks, sports, exercise) (Caspersen et al., Reference Caspersen, Powell and Christenson1985). Sedentary behaviour was defined as “energy expenditure ≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents of task (METs), while in a sitting, reclining or lying posture” (Sedentary Behaviour Research Network, 2012, p. 1).

e Gill, Jones, Zou, & Speechley (Reference Gill, Jones, Zou and Speechley2008).

f Washburn, Smith, Jette, & Janney (Reference Washburn, Smith, Jette and Janney1993).

g Craig et al., Reference Craig, Marshall, Sjöström, Bauman, Booth and Ainsworth2003.

IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery; CHAMPS = Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors.

Table 5. Quantitative outcomes of physical activity and sedentary behaviour for pre-post studies

Note. Only mean (SD) values were included unless specified.

a Quantitative outcomes for physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour were classified as either objective or self-report measures. Objective measures use tools (e.g., accelerometers) to report physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour, and can include accelerometry, step count, and energy expenditure. Self-report measures are when participants are asked to report their own physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour through questionnaires or surveys.

b We stratified studies by private, collective, or transition to collective dwelling. Private dwellings are either rented or owned property in the community (Statistics Canada, 2017b; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d). Collective dwellings include units where one lives amongst a collective of other older adults who receive support services (BC Seniors Living Association, 2021; Province of British Columbia, 2021; Statistics Canada, 2017a). If the study were observing older adults when they lived in a private dwelling and after they moved to a collective dwelling, we classified it as transition to collective dwelling.

c If specific mobility instruments were not used (e.g., SPPB), we reported available data on whether participants used mobility aids and on the prevalence of chronic conditions according to their study groups.

d Only quantitative physical activity and sedentary behaviour data were included. Specific instruments (e.g., CHAMPS), accelerometry, step count, energy expenditure, and study/investigator developed outcomes were reported only. We defined “physical activity” as energy expenditure by skeletal muscles (World Health Organization, 2020b) through various types of activities (e.g., household tasks, sports, exercise) (Caspersen et al., Reference Caspersen, Powell and Christenson1985). Sedentary behaviour was defined as “energy expenditure ≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents of task (METs), while in a sitting, reclining, or lying posture” (Sedentary Behaviour Research Network, 2012, p. 1).

e Baecke, et al., Reference Baecke, Burema and Frijters1982; Emplaincourt et al., Reference Emplaincourt, Schuler, Richardson, Wang and Abadie1997; Voorrips et al., Reference Voorrips, Ravelli, Dongelmans, Deurenberg and Van Staveren1991.

f Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Mills, King, Haskell, Gillis and Ritter2001.

g Kielhofner Reference Kielhofner2002.

SD = standard deviation; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery; CHAMPS = Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors.

Studies used accelerometry to report physical activity using the following activity monitors: ActiGraph GT1M (Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014a,Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Cortib), GT3X (Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Rai, Jongenelis, Jackson, Beck and Newton2020), GT3X+ (ActiGraph Corp., Pensacola, FL) (Park et al., Reference Park, Park, Hancox, Castaneda-Gameros and Koo2019; Regan et al., Reference Regan, Intzandt, Swatridge, Myers, Roy and Middleton2016), StepWatch 3.1 (Cyma, Corp., Mountlake Terrace, WA) (Cress et al., Reference Cress, Orini and Kinsler2011); and the SenseWear Armband (BodyMedia, Pittsburgh, PA) (Patry et al., Reference Patry, Vincent, Duval, Blamoutier, Briere and Boissy2019). Participants in collective dwellings engaged in moderate to vigorous physical activity, such as from 77.0 minutes per week (median) (Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014a) to 139.7 minutes per week (mean) in another study (Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Rai, Jongenelis, Jackson, Beck and Newton2020). Studies reported that older adults in private dwelling spent more time participating in light (Park et al., Reference Park, Park, Hancox, Castaneda-Gameros and Koo2019) and moderate to vigorous physical activity (Park et al., Reference Park, Park, Hancox, Castaneda-Gameros and Koo2019; Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Rai, Jongenelis, Jackson, Beck and Newton2020); and had greater step counts (Cress et al., Reference Cress, Orini and Kinsler2011) than their collective dwelling counterparts (Table 4).

Self-report measures for physical activity outcomes included: validated questionnaires (e.g., Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors [CHAMPS]) (Benzinger et al., Reference Benzinger, Iwarsson, Kroog, Beische, Lindemann and Klenk2014; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Wang, Tang, Chu and Chen2014; Cress et al., Reference Cress, Orini and Kinsler2011; Haney et al., Reference Haney, Fletcher and Robertson-Wilson2018; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Fisher, Lawson, Chad, Sheppard and Reeder2010; Joseph & Zimring, Reference Joseph and Zimring2007; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014a; Niva & Skär, Reference Niva and Skär2006; Perez-Hernandez et al., Reference Perez-Hernandez, Lopez-Garcia, Graciani, Luis Ayuso-Mateos, Rodriguez-Artalejo and Garcia-Esquinas2018; Portegijs et al., Reference Portegijs, Rantakokko, Viljanen, Rantanen and Iwarsson2017; van den Hombergh et al., Reference van den Hombergh, Schouten, van Staveren, van Amelsvoort and Kok1995); investigator- or study-developed instruments (Cress et al., Reference Cress, Orini and Kinsler2011; Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin and Kiefer2005; Lilja & Borell, Reference Lilja and Borell1997; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014b); qualitative interviews (Aplin et al., Reference Aplin, de Jonge and Gustafsson2015; Petersson et al., Reference Petersson, Lilja and Borell2012; Reid, Reference Reid2004; Thordardottir et al., Reference Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti and Ekstam2020) and focus groups on sedentary behaviour (Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020. In one study, the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Marshall, Sjöström, Bauman, Booth and Ainsworth2003) was used to determine that approximately 79 per cent of participants were sufficiently or highly active (Joseph & Zimring, Reference Joseph and Zimring2007). According to the CHAMPS (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Mills, King, Haskell, Gillis and Ritter2001), older adults from another study participated in exercise approximately 16 times a week (Haney et al., Reference Haney, Fletcher and Robertson-Wilson2018).

After moving into a collective dwelling, for some participants, the percent of daytime physical activity decreased (13.3–10.2%) and sedentary behaviour increased (86.7–89.7%) (Regan et al., Reference Regan, Intzandt, Swatridge, Myers, Roy and Middleton2016). Prior to home modifications, older adults spent 5.5 hours performing leisure activities, which increased to 7.5 hours after renovations (Niva & Skär, Reference Niva and Skär2006). The study also found that time spent at rest decreased from 11.5 hours to 9.0 hours (Niva & Skär, Reference Niva and Skär2006).

Indoor Features by Domains

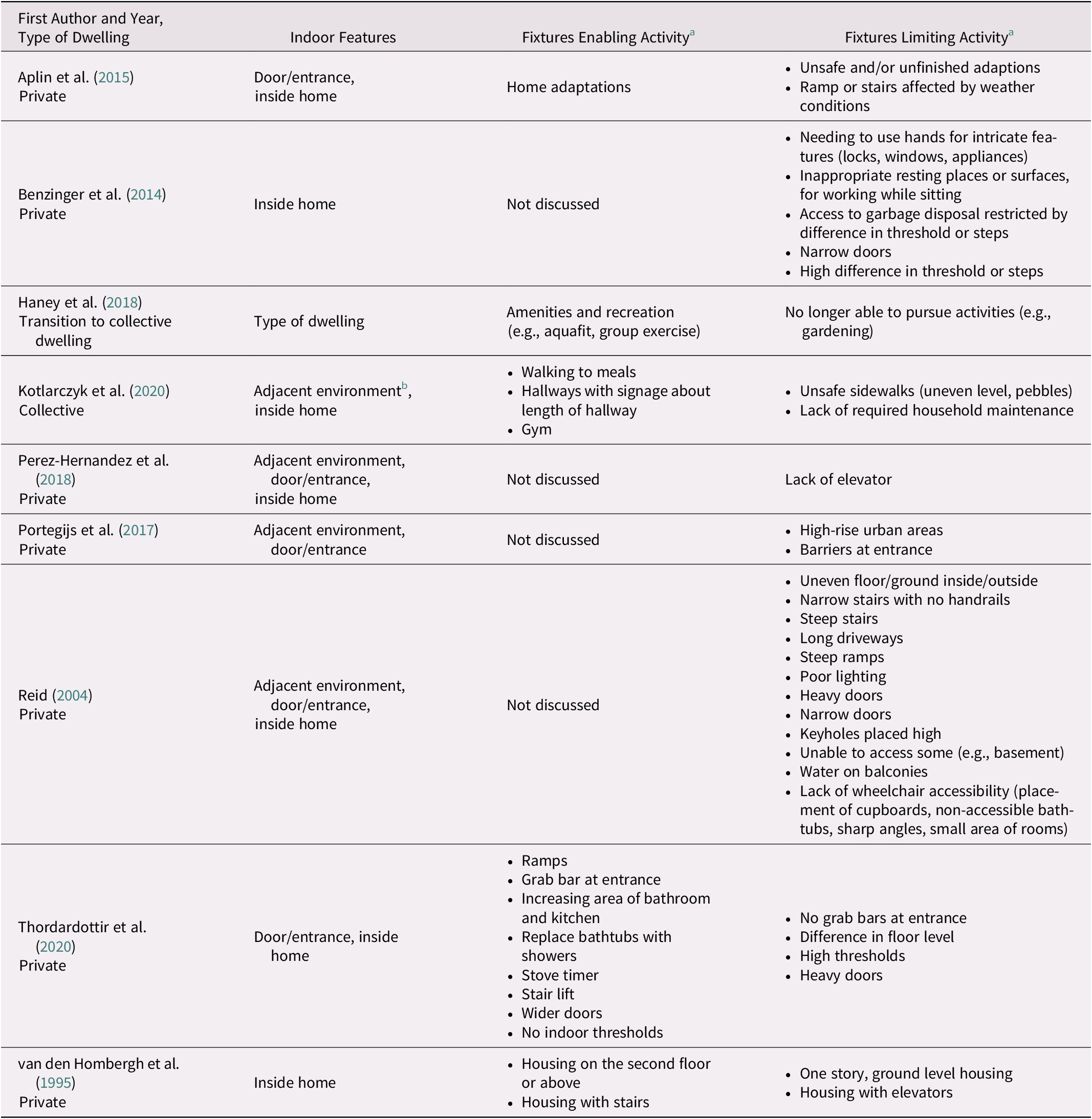

We categorized indoor environment features into the following three domains: campus, building, and fixtures. Figure 2 provides a summary of data synthesis. The campus domain encompassed features of the collective dwelling incorporating aesthetics and visibility, amenities and recreation, destinations, and outdoor pathways. The building domain included the following indoor features: area, floor level, and type of dwelling. The fixture domain consisted of the following features: elevators; indoor hallways; and stairs and ramps. Tables 6 and 7 describe how features were associated with physical activity and/or sedentary behavior.

Table 6. Influence of fixtures on activity

Note. This table provides further information on how the indoor features within the fixtures domain affects physical activity. This domain applies to both private and collective dwellings.

a “Activity” is defined as physical activity, which is energy expenditure by skeletal muscles (World Health Organization, 2020b) through various types of activities (e.g., household tasks, sports, exercise) (Caspersen et al., Reference Caspersen, Powell and Christenson1985).

b Adjacent environment includes spaces immediately outside the residential area, such as hallways, gardens, backyards, and front lawns (Peel et al., Reference Peel, Baker, Roth, Brown, Bodner and Allman2005).

Table 7. Influence of campus on activity

Note. This table provides further information on how the indoor features within the campus domain affect physical activity. This domain applies to collective dwellings only.

a “Activity” is defined as physical activity, which is energy expenditure by skeletal muscles (World Health Organization, 2020b) through various types of activities (e.g., household tasks, sports, exercise) (Caspersen et al., Reference Caspersen, Powell and Christenson1985).

Campus

Aesthetics and visibility

One study observed that older adults who perceived the retirement village campus as “more aesthetically pleasing features (i.e., having more trees, greenery, and pleasant natural features) were more likely to engage in more leisure walking” (Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014b, p. 10), whereas another study reported that the visibility of outdoor features (e.g., courtyards) was associated with uptake of physical activity (e.g., walking in the courtyard) (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin and Kiefer2005).

Amenities and recreation

Facilities offered amenities, recreational resources and/or activities (e.g., pools) (Haney et al., Reference Haney, Fletcher and Robertson-Wilson2018; Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin and Kiefer2005), exercise classes (Haney et al., Reference Haney, Fletcher and Robertson-Wilson2018; Regan et al., Reference Regan, Intzandt, Swatridge, Myers, Roy and Middleton2016), trips and scavenger hunts (Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020), and support for older adults to participate in physical activity (Haney et al., Reference Haney, Fletcher and Robertson-Wilson2018; Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin and Kiefer2005; Joseph & Zimring, Reference Joseph and Zimring2007; Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014a,Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Cortib; Regan et al., Reference Regan, Intzandt, Swatridge, Myers, Roy and Middleton2016; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020). Two studies demonstrated that a lack of amenities or activities limited older adults’ participation in physical activity (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin and Kiefer2005; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020). In contrast, access to amenities resulted in less opportunity to engage in ADLs, which may reduce light activities and increase sedentary behaviors (Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020).

Destinations

Destinations, including on-site gardens (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin and Kiefer2005), local shops, and clubhouses (Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014a,Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Cortib) promoted physical activity. Two studies reported that dining halls or similar destinations for eating meals encouraged walking (Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020), but also resulted in longer periods of sedentary time while older adults were served meals (Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020).

Outdoor pathways

Older adults observed that well-planned and connected paths influenced walking (Joseph & Zimring, Reference Joseph and Zimring2007). Longer path lengths, steep paths, and campuses with hills were associated with increased participation in recreational walking (Joseph & Zimring, Reference Joseph and Zimring2007).

Building

Area

Two studies observed that smaller spaces limited physical activity (Reid, Reference Reid2004; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020), and that renovations (e.g., bathroom expansions in private dwellings) increased engagement in ADLs (e.g. showering) (Thordardottir et al., Reference Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti and Ekstam2020). However, older adults experienced difficulties navigating and engaging in physical activity when retirement villages were too large (Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014a,Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Cortib).

Floor level

In private dwellings, high rise urban areas restricted physical activity (Portegijs et al., Reference Portegijs, Rantakokko, Viljanen, Rantanen and Iwarsson2017), and older adults had trouble moving between apartment floors (Lilja & Borell, Reference Lilja and Borell1997), whereas one-story, ground level houses were associated with increased physical activity (van den Hombergh et al., Reference van den Hombergh, Schouten, van Staveren, van Amelsvoort and Kok1995). Another study found no observed evidence between the apartment floor level and physical activity of older adults residing in high-rise retirement communities (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Wang, Tang, Chu and Chen2014).

Type of dwelling

There were differences in physical activity engagement across different dwellings. For example, older adults living in private dwellings participated in more physical activity (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Fisher, Lawson, Chad, Sheppard and Reeder2010; Park et al., Reference Park, Park, Hancox, Castaneda-Gameros and Koo2019; Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Rai, Jongenelis, Jackson, Beck and Newton2020),whereas some older adults in collective dwellings participated in less physical activity (Cress et al., Reference Cress, Orini and Kinsler2011; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Fisher, Lawson, Chad, Sheppard and Reeder2010; Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Rai, Jongenelis, Jackson, Beck and Newton2020). After relocating to a collective dwelling, older adults reported an increase in sedentary behaviours (Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020).

Fixtures

Elevators

Lack of access to an elevator restricted physical activity (Perez-Hernandez et al., Reference Perez-Hernandez, Lopez-Garcia, Graciani, Luis Ayuso-Mateos, Rodriguez-Artalejo and Garcia-Esquinas2018), whereas another study found that elevators limited physical activity (van den Hombergh et al., Reference van den Hombergh, Schouten, van Staveren, van Amelsvoort and Kok1995).

Indoor hallways

In collective dwellings, indoor hallways promoted walking (Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020), and older adults preferred to have “signs indicating the length of hallways as a way for residents to track their progress while walking” (Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020, p. 8).

Stairs and ramps

Older adults reported restrictions when participating in physical activity because of narrow stairs without hand rails, high steps, steep ramps (Reid, Reference Reid2004), and high threshold or step difference (Benzinger et al., Reference Benzinger, Iwarsson, Kroog, Beische, Lindemann and Klenk2014). These features also restricted access to spaces (e.g., waste disposal bins) (Benzinger et al., Reference Benzinger, Iwarsson, Kroog, Beische, Lindemann and Klenk2014). Conversely, ramps enabled physical activity (Thordardottir et al., Reference Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti and Ekstam2020).

Cross-cutting domains

Accessibility

Niva and Skär (Reference Niva and Skär2006) observed that the following modifications increased accessibility: removal of thresholds, new taps in the bathroom and kitchen, and wider doorways. Some housing features limited accessibility: narrow doors or doorways (Benzinger et al., Reference Benzinger, Iwarsson, Kroog, Beische, Lindemann and Klenk2014; Niva & Skär, Reference Niva and Skär2006; Reid, Reference Reid2004), heavy doors (Reid, Reference Reid2004), and thresholds and room design (Niva & Skär, Reference Niva and Skär2006). One study also discussed mobility limitations from insufficient “places to grab onto to help [older adults] through the entrance” (Reid, Reference Reid2004, p. 206).

Safety and environmental hazards

Safety and environmental hazards were identified as limiting physical activity for older adults. Kotlarczyk et al. (Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020) reported that pebbles and uneven sidewalks prevented older adults from walking outside in collective dwellings. In private dwellings, Reid (Reference Reid2004) found that the following safety and environmental hazards limited physical activity: uneven flagstones, cement, and floor; narrow stairs without handrails; long driveways or steep ramps; heavy doors; and water on balconies. Two studies also reported that safety affected participation in ADLs (Petersson et al., Reference Petersson, Lilja and Borell2012; Thordardottir et al., Reference Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti and Ekstam2020); and that improving safety through house modifications could enable older adults to engage in ADLs (Thordardottir et al., Reference Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti and Ekstam2020).

Discussion

This systematic review synthesizes evidence for a relationship between the indoor environment and physical activity in older adults. We found limited evidence for sedentary behaviour, but identified features of the relationship between the indoor environment and physical activity across three domains: campus, building, and fixtures. Features which enabled physical activity in the campus domain were: aesthetics (Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014a,Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Cortib), outdoor features (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin and Kiefer2005), amenities and recreation (Haney et al., Reference Haney, Fletcher and Robertson-Wilson2018; Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin and Kiefer2005; Joseph & Zimring, Reference Joseph and Zimring2007; Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014a,Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Cortib; Regan et al., Reference Regan, Intzandt, Swatridge, Myers, Roy and Middleton2016; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020), and destinations (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin and Kiefer2005; Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014a,Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Cortib; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020). Absence of amenities and recreational resources limited physical activity (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin and Kiefer2005; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020). However, the presence of dining halls and some amenities promoted sedentary behaviour by reducing the opportunity to engage in ADLs (Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020). For the building domain, greater area (Thordardottir et al., Reference Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti and Ekstam2020), ground level housing (van den Hombergh et al., Reference van den Hombergh, Schouten, van Staveren, van Amelsvoort and Kok1995), and private dwellings (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Fisher, Lawson, Chad, Sheppard and Reeder2010; Park et al., Reference Park, Park, Hancox, Castaneda-Gameros and Koo2019; Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Rai, Jongenelis, Jackson, Beck and Newton2020) promoted physical activity. Sedentary behaviour reportedly increased after transition to a collective dwelling (Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020). The following features hindered physical activity in the building domain: smaller area (Reid, Reference Reid2004; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020), larger retirement village campuses (Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014a,Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Cortib), high-rise buildings (Lilja & Borell, Reference Lilja and Borell1997; Portegijs et al., Reference Portegijs, Rantakokko, Viljanen, Rantanen and Iwarsson2017), and collective dwellings (Cress et al., Reference Cress, Orini and Kinsler2011; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Fisher, Lawson, Chad, Sheppard and Reeder2010; Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Rai, Jongenelis, Jackson, Beck and Newton2020). In the last domain, fixtures which supported physical activity included indoor hallways (Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020), and ramps (Thordardottir et al., Reference Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti and Ekstam2020). Stairs which were narrow and without handrails, steep ramps (Reid, Reference Reid2004), and high threshold or step differences (Benzinger et al., Reference Benzinger, Iwarsson, Kroog, Beische, Lindemann and Klenk2014) restricted physical activity. The presence of elevators (van den Hombergh et al., Reference van den Hombergh, Schouten, van Staveren, van Amelsvoort and Kok1995), along with the lack of access to elevators (Perez-Hernandez et al., Reference Perez-Hernandez, Lopez-Garcia, Graciani, Luis Ayuso-Mateos, Rodriguez-Artalejo and Garcia-Esquinas2018), also limited physical activity. Indoor features related to safety and environmental hazards also impeded engagement in physical activity, such as uneven floors (Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020; Reid, Reference Reid2004).

Our review observed that the availability of amenities and recreational resources, such as golf courses and pools, can increase participation in physical activity for older adults living in collective dwellings (Haney et al., Reference Haney, Fletcher and Robertson-Wilson2018; Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Zimring, Harris-Kojetin and Kiefer2005; Joseph & Zimring, Reference Joseph and Zimring2007; Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014a,Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Cortib; Regan et al., Reference Regan, Intzandt, Swatridge, Myers, Roy and Middleton2016; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020). Another systematic review highlighted how the type of facility can affect sedentary behaviour: amenities related to exercise were associated with lower sedentary behaviour, whereas socialization or educational activities (e.g., salons, music rooms) were associated with greater sedentary behaviour (Ahrentzen & Tural, Reference Ahrentzen and Tural2015). Despite access to these resources, other work observed that only half of the amenities were used by older adults living in retirement villages (Holt, Lee, Jancey, Kerr, & Howat, Reference Holt, Lee, Jancey, Kerr and Howat2016). This finding suggests that simply increasing the number of and/or access to amenities is not enough to increase uptake of physical activity. The Model of Human Occupation proposes that volition (characterized by people’s values and interests) can affect engagement in activities (Kielhofner & Burke, Reference Kielhofner and Burke1980). Specifically, people are more likely to engage in activities that they find meaningful (Kielhofner & Burke, Reference Kielhofner and Burke1980). Behaviour strategies and identification of possible barriers to and facilitators of physical activity engagement should also be considered (Jancey et al., Reference Jancey, Clarke, Howat, Lee, Shilton and Fisher2008). Evidence suggests that peer leaders, staff, or facilitators are more influential in the uptake of physical activity, than is access to recreational amenities (Ahrentzen & Tural, Reference Ahrentzen and Tural2015; Dorgo et al., Reference Dorgo, Robinson and Bader2009; Jancey et al., Reference Jancey, Clarke, Howat, Lee, Shilton and Fisher2008 as cited in Holt et al., Reference Holt, Lee, Jancey, Kerr and Howat2016;). Therefore, it simply may not be enough to build facilities. The social environment and other behaviour strategies play a role in the adoption and maintenance of physical activity (Annear et al., Reference Annear, Keeling, Wilkinson, Cushman, Gidlow and Hopkins2014).

Ahrentzen and Tural (Reference Ahrentzen and Tural2015) included people with dementia in their systematic review of active aging across dwellings. Similar to our findings, their review observed that steep ramps hindered physical activity (Ahrentzen & Tural, Reference Ahrentzen and Tural2015). They also noted higher step counts were associated with larger areas and communal dwellings, whereas home modifications enabled participation in ADLs (Ahrentzen & Tural, Reference Ahrentzen and Tural2015), which are consistent with our findings. The review (Ahrentzen & Tural, Reference Ahrentzen and Tural2015) had more results for sedentary behaviour, reporting that the frequency of indoor hallways was associated with less sedentary behaviour (Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Carlson, Sallis, Rosenberg, Leak, Saelens, Chapman, Frank, Cain, Conway and King2011 as cited in Ahrentzen & Tural, Reference Ahrentzen and Tural2015). Another review found that the “smoothness” of paths, accessibility, and safety increased participation in physical activity (Annear et al., Reference Annear, Keeling, Wilkinson, Cushman, Gidlow and Hopkins2014). However, the review reported that “poor-quality” (p. 602) pathways served as a barrier to physical activity (Annear et al., Reference Annear, Keeling, Wilkinson, Cushman, Gidlow and Hopkins2014), which our review did not find. However, these differences may be because of the different populations under study: one review included people with dementia (Ahrentzen & Tural, Reference Ahrentzen and Tural2015), and other reviews studied the implications of social and societal effects (e.g., relationships with staff working at collective dwellings, poverty) (Ahrentzen & Tural, Reference Ahrentzen and Tural2015; Annear et al., Reference Annear, Keeling, Wilkinson, Cushman, Gidlow and Hopkins2014).

We observed several illustrations of the connection between the older adult and their environment. Different settings could potentially support specific types of physical activity: Older adults in collective dwellings often do not engage in as many ADLs because they receive services from the facility (e.g., prepared meals reduce the need to cook) (Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020). Similarly, older adults can influence their environments. For example, when older adults move to collective dwellings because of functional decline (Crisp, Windsor, Butterworth, & Anstey, Reference Crisp, Windsor, Butterworth and Anstey2013), they often move into a space smaller than their previous private dwelling (Hansen & Gottschalk, Reference Hansen and Gottschalk2006). Another study observed that hills promoted recreational physical activity (Joseph & Zimring, Reference Joseph and Zimring2007), whereas some evidence demonstrates challenges with using hills on campus (Holt et al., Reference Holt, Lee, Jancey, Kerr and Howat2016). Perez-Hernandez et al. (Reference Perez-Hernandez, Lopez-Garcia, Graciani, Luis Ayuso-Mateos, Rodriguez-Artalejo and Garcia-Esquinas2018) noted that lack of access to elevators restricted physical activity (Perez-Hernandez et al., Reference Perez-Hernandez, Lopez-Garcia, Graciani, Luis Ayuso-Mateos, Rodriguez-Artalejo and Garcia-Esquinas2018), whereas van den Hombergh et al. (Reference van den Hombergh, Schouten, van Staveren, van Amelsvoort and Kok1995) found that elevators limited physical activity (van den Hombergh et al., Reference van den Hombergh, Schouten, van Staveren, van Amelsvoort and Kok1995). This discrepancy may be explained in two ways: lack of access to elevators restricts the frequency of older adults leaving their homes, resulting in decreased physical activity; and/or access to elevators results in reduced use of stairs, which could also impact overall physical activity. Elevators and stairs are dependent on people’s mobility. For those without restrictions, stairs can help maintain physical activity and function.

The intricate relationship between older adults and their environments can be understood through the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagement (CMOP-E) (Law et al., Reference Law, Cooper, Strong, Stewart, Rigby, Letts, Christiansen and Baum1977; Townsend & Polatajko, Reference Townsend and Polatajko2007) and the person–environment fit framework (Su, Murdock, & Rounds, Reference Su, Murdock, Rounds, Hartung, Savickas and Walsh2015). The CMOP-E explains how the person, environment, and occupation (defined as a person’s role in an environment [Warren, Reference Warren2002]) interact when people are engaging in various behaviours (Law et al., Reference Law, Cooper, Strong, Stewart, Rigby, Letts, Christiansen and Baum1977; Townsend & Polatajko, Reference Townsend and Polatajko2007). The person–environment fit framework suggests that “people shape their environments and environments shape people” (Rounds & Tracey, Reference Rounds, Tracey, Walsh and Osipow1990 as cited in Su et al., Reference Su, Murdock, Rounds, Hartung, Savickas and Walsh2015, p. 83). The CMOP-E and person–environment fit apply here, such as how functional decline can result in an older adult moving into a smaller home (Crisp et al., Reference Crisp, Windsor, Butterworth and Anstey2013; Hansen & Gottschalk, Reference Hansen and Gottschalk2006), which may not provide as many opportunities for physical activity (Reid, Reference Reid2004; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020).

Accessibility and safety were cross-cutting domains because they can impact multiple levels (campus, building, and fixtures) of the indoor environment. Evidence suggests that limitations in accessibility are negatively correlated with physical activity in adults with disabilities (Saebu, Reference Saebu2010). Older adults in both private and collective dwellings reported that hazards such as uneven grounds or floors prevented participation in physical activity (Kotlarczyk et al., Reference Kotlarczyk, Hergenroeder, Gibbs, de Abril Cameron, Hamm and Brach2020; Reid, Reference Reid2004). This finding is supported by other evidence which report that “obstructions on the pathway” (Holt et al., Reference Holt, Lee, Jancey, Kerr and Howat2016, p. 408) were a barrier to walking in collective dwellings (Holt et al., Reference Holt, Lee, Jancey, Kerr and Howat2016). Private dwellings often require modifications, such as the installation of ramps or grab bars, to increase both accessibility and safety (Niva & Skär, Reference Niva and Skär2006; Thordardottir et al., Reference Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti and Ekstam2020), demonstrating their synergistic relationship, and can encourage engagement in ADLs (Ahrentzen & Tural, Reference Ahrentzen and Tural2015). Accessibility and safety are integral to Universal Design principles (Connell et al., Reference Connell, Jones, Mace, Mueller, Mullick and Ostroff1997; Null, Reference Null2013a).

The findings from this synthesis align well with the seven principles of Universal Design (Null, Reference Null2013b): “products, environments, programmes and services to be usable by all people… without the need for adaptation or specialized design” (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2021). Housing and campus design should consider that features such as safety and aesthetics (Equitable Use), how older adults choose to use outdoor campus pathways (Flexibility of Use), minimizing hazards such as uneven floors (Error Tolerance), managing heavy doors (Reid, Reference Reid2004; Thordardottir et al., Reference Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti and Ekstam2020) (Physical Effort), and living space (Size and Space for Approach and Use) may influence older adult’s participation in physical activity (Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Corti2014a, Reference Nathan, Wood and Giles-Cortib; Reid, Reference Reid2004; Thordardottir et al., Reference Thordardottir, Fange, Chiatti and Ekstam2020; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Pope and Copeland2020). Universal Design principles coincide with the Global Age-Friendly Cities Project (World Health Organization, 2010). Older adults sometimes reside in older housing which may require retrofitting according to Universal Design principles. Although designing activity-friendly housing from the beginning is ideal, initiatives such as Complete Streets (for outdoor environments) (Transport Canada, 2009, p. 1), provides an example of retrofitted infrastructure to accommodate all people, and could be considered within the housing sector to promote healthy, active aging in place.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study included all studies regardless of language, dwelling, or study design. Because our review only included studies from higher income countries, the results may not be representative of other regions. Only a limited number of studies reported data on race/ethnicity; therefore, the findings may not be generalizable.

The inclusion of both qualitative and quantitative studies strengthened our review, as we could draw upon different data. Although only one author extracted data, we tried to mitigate risk by having a second author review and complete data extraction for 10 per cent of the studies. Our review did not exclude studies of low quality; however, only one study had a quality score under 0.85/1.00. Differences in physical activity engagement could arise from varying functional mobility of older adults across dwellings, and/or the level of care that older adults received in their residence (e.g., laundry services). Further, we located limited findings for indoor features and sedentary behaviour. Finally, we did not review the relationships of physical activity or sedentary behavior and (i) social environment or (i) health care costs.

Implications of the Main Findings

The findings of this synthesis could inform future housing policy. As the population of older people increases globally, governments may need to focus on providing activity-supportive housing and/or retrofitting pre-existing infrastructure to support accessibility and physical activity.

Future Research and Recommendations

Although our study explored the effects of indoor environment on physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour, future studies should take the social environment and health care costs into consideration. Future studies should investigate the relationship between the indoor environment and sedentary behavior. Understanding this relationship can assist with designing indoor environments, which may reduce prolonged periods of sedentary behaviour. We need more research to inform retrofitting existing infrastructure, physical activity, and Universal Design principles in an effective and efficient manner. In the long term, future research or policy could consider developing a rating system for evaluating physical-activity-friendly buildings for aging in place. Additional research is needed for low- and middle-income countries to improve representation and generalizability, especially as the studies included in this review were from higher-income countries. Further, for studies conducted in higher-income countries, greater diversity of study participants should be included in future research. We also encourage researchers to report data for race/ethnicity, as only four studies included these data in this synthesis.

This systematic review was registered at PROSPERO: CRD42018095359.

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the Canada Research Chairs Program for career support of Professor Ashe.