Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic disproportionately affected long-term care homes (LTCHs) across the world. The rapidly changing landscape and uncertainty associated with the pandemic presented overwhelming challenges to all LTCH employees. Older adults residing in LTCHs are living with more complex care needs than ever before (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Lane, Tanuseputro, Mojaverian, Talarico and Wodchis2020), and as LTCH employees face aggravating working conditions during the pandemic, their ability to deliver excellent care was compromised. LTCH employees cite a plethora of negative outcomes during the last couple of years, including, but not limited to, experiences of burnout (White, Wetle, Reddy, & Baier, Reference White, Wetle, Reddy and Baier2021), job dissatisfaction (Cimarolli, Bryant, Falzarano, & Stone, Reference Cimarolli, Bryant, Falzarano and Stone2021), and moral distress due to an inability to provide quality care (Iaboni et al., Reference Iaboni, Quirt, Engell, Kirkham, Stewart and Grigorovich2022). Early in the pandemic, a group of international LTCH researchers raised concerns about protecting the health and well-being of LTCH employees, in particular, the staff involved in direct care (McGilton et al., Reference McGilton, Escrig-Pinol, Gordon, Chu, Zúñiga and Sanchez2020). Based on input from international LTCH organizations, McGilton et al. synthesized four categories of evidence-informed recommendations to support staff and urged international LTCH leaders to implement them (McGilton et al., Reference McGilton, Escrig-Pinol, Gordon, Chu, Zúñiga and Sanchez2020). The recommendations consist of 33 interventions targeted at providing LTCH employees with clear direction and guidance, prioritizing their health, implementing human resource policies, providing education and training, and acquiring sufficient personal protective equipment.

Based on the recommendations proposed by McGilton et al. (Reference McGilton, Escrig-Pinol, Gordon, Chu, Zúñiga and Sanchez2020), this study employed a community-based participatory approach and focused on developing and adapting a huddle intervention in partnership with an LTCH, to address their specific challenges encountered during the pandemic. Huddles are brief, structured, interdisciplinary meetings that occur between health care team members at regular time intervals to engage participants in reflection on opportunities for improvement and plan for their resolution (Di Vincenzo, Reference Di Vincenzo2017; Dutka, Reference Dutka2016). Huddles can serve multiple purposes, such as identifying items requiring immediate attention (Donnelly et al., Reference Donnelly, Cherian, Chua, Thankachan, Millecker and Koroll2016; Martin & Ciurzynski, Reference Martin and Ciurzynski2015), coordinating care (Freitag & Carroll, Reference Freitag and Carroll2011; Martin & Ciurzynski, Reference Martin and Ciurzynski2015), and providing updates on the work environment (Goldenhar, Brady, Sutcliffe, & Muething, Reference Goldenhar, Brady, Sutcliffe and Muething2013). Huddles can encourage a safety culture through standardized interactions among staff (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Ward, Vaughan, Murray, Zena and O’Connor2019) and can be employed as a tool to share information regarding patient safety (Melton et al., Reference Melton, Lengerich, Collins, McKeehan, Dunn and Griggs2017). Use of scripts, checklists, and algorithms can help enhance user confidence, participation, and navigation of risk situations during huddles (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Ward, Vaughan, Murray, Zena and O’Connor2019). To ensure efficiency of huddles, a detailed discussion of items requiring follow-up needs to occur after the huddle is complete (Fencl & Willoughby, Reference Fencl and Willoughby2018).

A recent scoping review of huddles’ effectiveness in health care settings conducted by Pimentel et al. (Reference Pimentel, Snow, Carnes, Shah, Loup and Vallejo-Luces2021) found that 66 per cent of the included studies described some improvements in team outcomes, including communication and collaboration; 45 per cent of the studies demonstrated improvements in situational awareness; 30 per cent of the studies showed improvements in staff satisfaction; 27 per cent increased the staff’s sense of a supportive climate; and 20 per cent enhanced huddle participants’ self-efficacy in providing better care. Effective communication is important in improving resident outcomes (Arling, Abrahamson, Miech, Inui, & Arling, Reference Arling, Abrahamson, Miech, Inui and Arling2013; Boscart et al., Reference Boscart, Heckman, Huson, Brohman, Harkness and Hirdes2017), and huddles can provide an opportunity to discuss communication challenges and identify strategies to address them (Leonard, Graham, & Bonacum, Reference Leonard, Graham and Bonacum2004). Additionally, huddles serve as a forum to discuss and resolve situations the staff find distressing, which can help mitigate moral distress (Pijl-Zieber et al., Reference Pijl-Zieber, Hagen, Armstrong-Esther, Hall, Akins and Stingl2008).

Although the majority of studies describe huddles’ implementation in acute care settings (Pimentel et al., Reference Pimentel, Snow, Carnes, Shah, Loup and Vallejo-Luces2021), huddles have been successfully implemented in LTCHs. For instance, in one LTCH, interdisciplinary team meetings comparable to huddles were initiated after a resident fall; residents’ plans of care were updated after meeting discussions, leading to a reduction in falls (Zubkoff et al., Reference Zubkoff, Neily, Quigley, Delanko, Young-Xu and Boar2018). In another home, weekly mobility care huddles were carried out, leading to improvements in resident-centred mobility care (Taylor, Barker, Hill, & Haines, Reference Taylor, Barker, Hill and Haines2015). In a study by Wagner et al. (Reference Wagner, Huijbregts, Sokoloff, Wisniewski, Walsh and Feldman2014), mental health huddles were implemented on dementia care units to provide all staff with an opportunity to create resident-centred solutions to respond to responsive behaviours, which improved staff outcomes, such as collaboration, teamwork, support, and communication.

Competence of the intervention champion is integral to the successful implementation of practices new to the environment (Kitson, Harvey, & McCormack, Reference Kitson, Harvey and McCormack1998). Therefore, the characteristics of the huddle facilitator responsible for implementation are important for success. A nurse practitioner (NP) was chosen as the huddle facilitator due to the NP’s multifaceted role in LTCH. NPs are graduate-prepared registered nurses who, as part of their clinical responsibilities, assess, diagnose, and treat patients/residents in collaboration with other health care professionals (NPAO, 2022). Evidence indicates that, in addition to their clinical role, NPs assume leadership responsibilities, including mentoring, educating, and supporting care employees (Kane, Flood, Keckhafer, & Rockwood, Reference Kane, Flood, Keckhafer and Rockwood2001; Sangster-Gormley et al., Reference Sangster-Gormley, Carter, Donald, Misener, Ploeg and Kaasalainen2013; Stolee, Hillier, Esbaugh, Griffiths, & Borrie, Reference Stolee, Hillier, Esbaugh, Griffiths and Borrie2006). In this collaboration, NPs build the staff’s capacity to optimize resident care through mentorship and guidance (Sangster-Gormley et al., Reference Sangster-Gormley, Carter, Donald, Misener, Ploeg and Kaasalainen2013). Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, NPs stepped up as leaders and supported LTCH teams in many homes across Canada and the U.S. (McGilton et al., Reference McGilton, Krassikova, Boscart, Sidani, Iaboni and Vellani2021; Thomas-Gayle & Muller, Reference Thomas-Gayle and Muller2021). In their unique position, NPs are ideally situated to implement new practices, as demonstrated by previous research using NPs as change champions (Kaasalainen et al., Reference Kaasalainen, Ploeg, Donald, Coker, Brazil and Martin-Misener2015). The purpose of this study was to develop and adapt an NP-led huddles implementation toolkit to the context of a LTCH and evaluate the acceptability of the toolkit, as perceived by the LTCH managers and staff participating in the huddles.

Methods

This study involved toolkit development and adaptation through a four-step process: (1) encouraging stakeholder engagement and capacity-building; (2) developing the toolkit; (3) adapting the toolkit; and (4) evaluating the toolkit’s acceptability (Figure 1). The study was reviewed and approved by the University Health Network (UHN) Research Ethics Board (REB #20-6298).

Figure 1. Stages of intervention development and adaptation.

This work was guided by the principles of a community-based participatory approach to research (CBPR). As described by Collins et al. (Reference Collins, Clifasefi, Stanton, Straits, Gil-Kashiwabara and Espinosa2018), this approach emphasizes collaboration between researchers and community partners to identify and directly address the needs of the community. Therefore, phase 1 began with recruiting an NP employed in an LTCH through the Nurse Practitioners Association of Ontario (NPAO). The characteristics of the LTCH included: located in a rural area; privately owned; not-for-profit; and < 150 beds split among five units. Once the NP and the administrator of the LTCH where the NP was employed committed to the project, a project team consisting of LTCH employees was recruited to aid in developing and adapting the toolkit to the home. The project team comprised seven individuals, three representing the leadership and administrative staff (CEO, director of care, and risk management and quality assurance lead) and four care staff (NP, registered nurse, registered practical nurse, and recreation facilitator). The NP provided care in the home on a contract basis for 8 hours per week as well as acute, episodic care as a member of an outreach team. For 2 months at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the NP was deployed to the home by the outreach team to provide full-time support. The NP was provided with a $2,500 honorarium for the additional work related to planning and implementing this project. The project team members were given an overview of the study and were asked to identify areas for improvement based on their experiences during the first two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on consensus, they identified two opportunities for improvement: (a) the need for better communication between the staff and managers, and (b) strategies to address the staff’s moral distress and COVID-19 fatigue. In addition to the project team, two other stakeholders were consulted by the research team throughout the project: an NP with LTC experience but who did not provide care at the LTCH and an individual with lived experience as a care partner (MK) of a family member in an LTCH. The project team members received a $20 gift card for participation. Through formal and informal meetings, the knowledge provided by the project team, the NPs, and the care partner was used to inform the toolkit design.

Developing the NP-Led Huddle Toolkit

The researchers reviewed the LTCH’s concerns and mapped them to the recommendations proposed by McGilton et al. (Reference McGilton, Escrig-Pinol, Gordon, Chu, Zúñiga and Sanchez2020). Out of the 33 recommendations made by McGilton et al. (Reference McGilton, Escrig-Pinol, Gordon, Chu, Zúñiga and Sanchez2020) to support staff, the concerns identified by staff within the LTCH best aligned with “promoting daily huddles with staff to provide updates and address concerns.” This mapping exercise resulted in the development of a huddle toolkit. Huddles were determined to be the most applicable intervention to address the areas for improvement identified by the team members from the LTCH. The researchers reviewed the literature, with a particular focus on sources describing implementation of huddles in LTCH, to prepare an initial version of a toolkit summarizing information on the huddles intervention, including its goals, components, and activities (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen2018; Di Vincenzo, Reference Di Vincenzo2017; Dutka, Reference Dutka2016; Edbrooke-Childs et al., Reference Edbrooke-Childs, Hayes, Sharples, Gondek, Stapley and Sevdalis2017; Melton et al., Reference Melton, Lengerich, Collins, McKeehan, Dunn and Griggs2017; Pimentel et al., Reference Pimentel, Snow, Carnes, Shah, Loup and Vallejo-Luces2021, Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Ward, Vaughan, Murray, Zena and O’Connor2019; Traynor, Reference Traynor2015). Subsequent bi-weekly meetings were held with the NP and the care partner to discuss and further adapt the toolkit; their knowledge and experience were used to ensure applicability to the LTCH context, the design matched the NP’s roles and responsibilities, and the toolkit components addressed the identified concerns.

Adaptation of the Toolkit

When the toolkit was finalized, the project team members were invited to participate in a 2-hour virtual workshop to gather feedback to refine and tailor the toolkit to the context of the LTCH. The workshop was led by the PI (KM) and included an introduction to the toolkit and its associated components, followed by an interactive discussion. The discussion was guided by questions related to the acceptability of the huddles (Do you consider the huddles appropriate in addressing the challenges identified in your LTCH?), feasibility of the huddles (Will you be able to carry out the huddles?), as well as changes required to the toolkit (What changes need to be carried out to make the toolkit more suitable to the context of the LTCH?). The adaptable aspects of the huddles (mode, dose, and delivery) were individualized to the LTCH, accordingly. A research assistant (AW) took field notes and tracked adaptation steps and decisions made related to changes in the intervention.

Acceptability Evaluation

Acceptability of the toolkit was evaluated using a quantitative measure and qualitative interviews. The project team members were asked to rate the toolkit’s acceptability via an anonymous poll using the Treatment Acceptability Questionnaire (TAQ) at the end of the workshop (Sidani, Epstein, Bootzin, Moritz, & Miranda, Reference Sidani, Epstein, Bootzin, Moritz and Miranda2009). The TAQ measures individuals’ perceptions of an intervention pertaining to four attributes: acceptability (How acceptable/logical does the toolkit seem to you?), suitability (How suitable/appropriate does the toolkit seem to be to address the workforce challenges?), effectiveness (How effective do you think the toolkit will be in improving the workforce challenges?), and willingness to comply (How willing are you to comply with the huddles?). Individuals were asked to rate each attribute on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “Not at all” (1) to “Very much” (5). The TAQ has demonstrated high internal consistency reliability (α > 0.80) and validity in previous research (Sidani et al., Reference Sidani, Epstein, Bootzin, Moritz and Miranda2009). The total score reflects overall level of perceived acceptability, where higher scores indicate more favourable perceptions.

Qualitative interviews occurred after a 4-month implementation period, during which 48 huddles were carried out by the NP on two units in one LTCH. Interviews assessed the experiences of LTCH staff participating in the huddles. Recruitment posters were shared on the two implementation units, inviting staff interested in sharing their experiences to contact the research coordinator (AK). In addition, administrative employees who were part of the project team were interviewed. Interviews were conducted over the telephone by the research coordinator with a note-taker (AW) on the line. A semi-structured interview guide was utilized to encourage interviewees to reflect on the design quality, describe what did and did not work well with the huddles, and make any recommendations for improvement. Before the interview, participants were asked to complete a demographic questionnaire, collecting information on their age, gender, ethnicity, role in the LTCH, years of work experience in their current role, and overall years of work experience in LTCH.

Each interview lasted 30 minutes on average, was audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Prior to the interview, all individuals provided informed written consent electronically. All interviewees received a $20 e-gift card after the interview in appreciation for their time.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were utilized to summarize the demographic characteristics of interviewed participants. For the TAQ, a total scale score was computed as the mean of the four items’ scores. A manifest content analysis was employed to describe what is observable in the interview transcripts (Bengtsson, Reference Bengtsson2016). A content analysis was completed by two researchers (AK and AW), who independently reviewed the full data set and assigned codes line by line to capture the topics present in the text. After each transcript, the two researchers met to reconcile differences; the care partner (MK) attended the meetings to review the codes with the researchers. All data were coded into three pre-determined categories: design quality, limitations, and recommendations. In addition, results were periodically shared with the rest of the research team. Trustworthiness and credibility were observed through independent coding, systematic data management, and a detailed documentation trail.

Results

Toolkit

The final toolkit is made up of two sections and includes components sourced from the literature that have been found useful for initiating and facilitating huddles. The toolkit can be accessed online (https://www.encoarteam.com/huddlestoolkit).

Section 1

Section 1 includes a brief description of huddles and their purpose, a set of ground rules, communication strategies and strategies to identify huddle topics, as well as tools to reflect on the huddles and the discussed topics. Section 1 begins with an introduction to huddles and provides a summary of research demonstrating huddles’ effectiveness in improving staff and resident outcomes. The introduction is followed by eight ground rules, based on a list of recommended practices identified in a systematic review of safety briefings by Ryan et al. (Reference Ryan, Ward, Vaughan, Murray, Zena and O’Connor2019). The ground rules are a key component of the toolkit to ensure standardization of core huddles components and reduce variability in their implementation. Following the ground rules, strategies for effectively communicating in huddles and choosing huddle topics are summarized. These components were added based on the feedback provided by the LTCH project team.

The toolkit also contains tools to record, reflect on, and track the huddles. For example, a Huddle Observation Tool (HOT), previously used in paediatric units, was adapted by the research team to be used in the context of LTC (Edbrooke-Childs et al., Reference Edbrooke-Childs, Hayes, Sharples, Gondek, Stapley and Sevdalis2017). The HOT was developed and validated to aid huddle facilitators to record and reflect on the information exchanges during huddles in a structured manner. The HOT is composed of two parts; the first part can be used to record huddle elements and participants, whereas the second part provides opportunities to reflect on huddle structure, environment, collaborative culture, and risk management. Finally, the toolkit provides two strategies for tracking topics and progress on developed action items, in which a whiteboard is posted at the nursing stations on the two implementation units to be easily accessed by staff. Employees can suggest topics for huddle discussion by writing directly on the whiteboard and assigning the topics a priority status, or by completing opportunity for improvement (OFI) cards and posting them to the board. A stack of blank OFI cards should be provided and accessible to all staff (for example, at the nurse station). In both cases, topics can be suggested anonymously. As the topics are brought up and addressed at the huddles, their status (to be addressed / in progress / on hold / complete) is updated on the whiteboard, to visualize progress.

Section 2

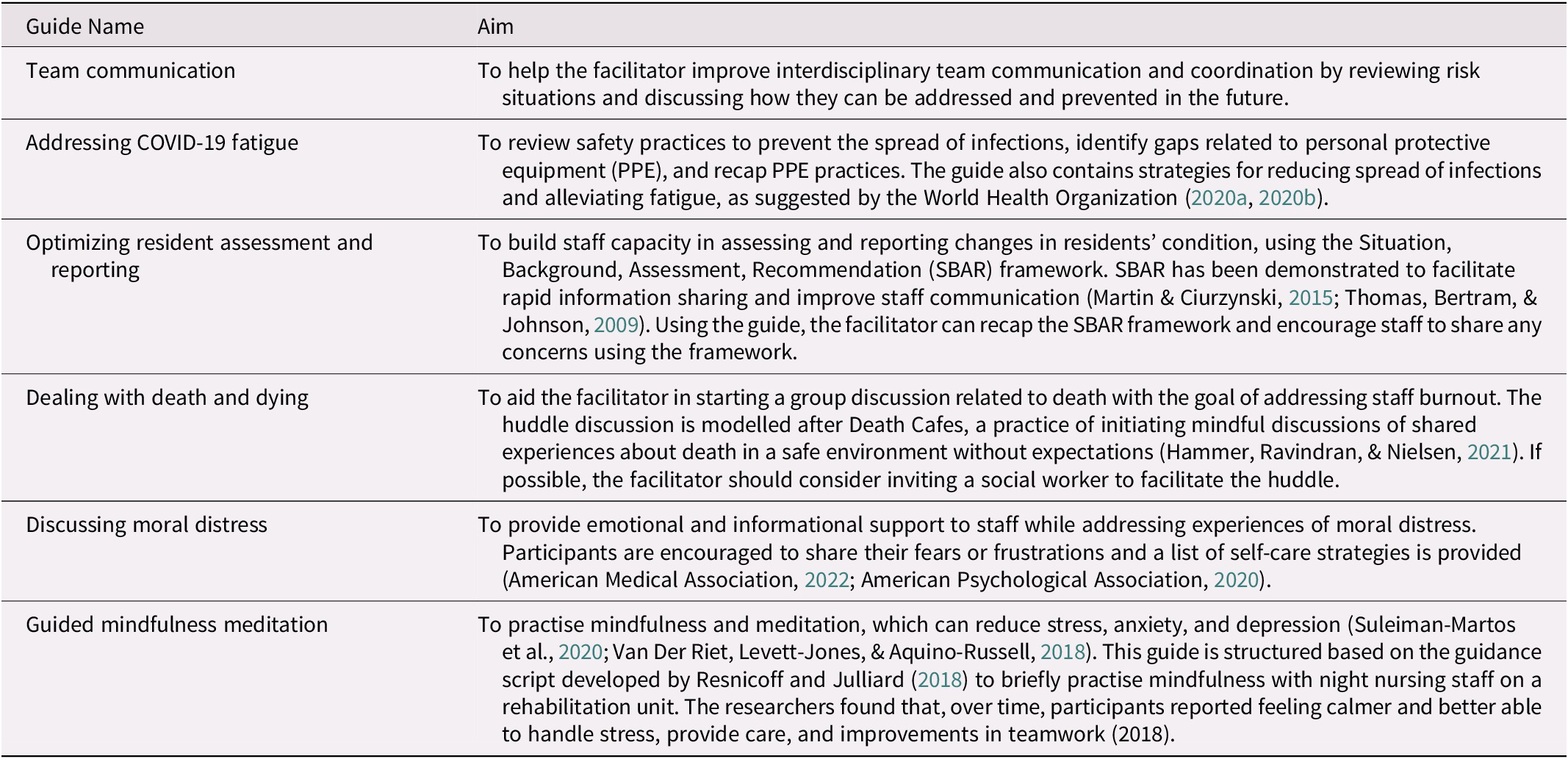

Section 2 is composed of six guides. Guides addressing different topics were developed based on needs identified by the project team: improving communication, COVID-19 fatigue, optimizing resident assessment, dealing with death and dying, discussing moral distress, and guided mindfulness meditation. A blank guide with a general script that does not address a specific topic is also included. The huddle facilitator can adapt this script to discuss unplanned topics not contained in the toolkit, for example, an opportunity to optimize resident care. All guides follow the same structure, adapted from the Clinical Excellence Commission (2020). The scripts are made up of four parts and are designed to last no longer than 15 minutes. Each huddle starts with an “opening,” where the huddle topic and aim are stated and at least one positive event from the past week is shared. Next, participants are invited to “look back” and reflect on the topic that will be discussed at the huddle. The “looking now” section makes up the majority of the huddle discussion and provides huddle participants with an opportunity to address how the aim can be achieved. The huddle is ended with “planning,” where participants can summarize the discussion and assign accountability. All huddles are closed with positive reinforcement to staff. Topics addressed in pre-developed guides can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of the guides contained in the toolkit and their aims

Acceptability Evaluation

The overall acceptability of the huddle toolkit was rated as high (4.08 of 5.00) by the project team members (n = 6). Fifty per cent of the members believed that the huddles would be very much or very effective, 84 per cent of respondents identified the huddles as very much or very acceptable and suitable, and all individuals indicated they would be very much or very willing to comply with the huddles.

Huddles were held at the nurse stations with employees working day (13:45–14:00) and evening shifts (14:00–14:15). The times for the huddles were determined by the staff and the NP, and a poster with the huddles’ schedule was posted at the nurse station as a reminder. For the first 2 weeks, the NP held huddles daily from Monday to Friday; these were scaled back to twice weekly based on staff feedback. Toolkit guides were used for each huddle to ensure all huddles followed the same structure. The topics for each huddle were selected by the NP based on priority as identified by staff in the OFI cards. The NP would then select a guide that best addressed the chosen topic. When an issue not addressed by the six guides in the toolkit was identified, the NP utilized the blank guide to conduct the huddle.

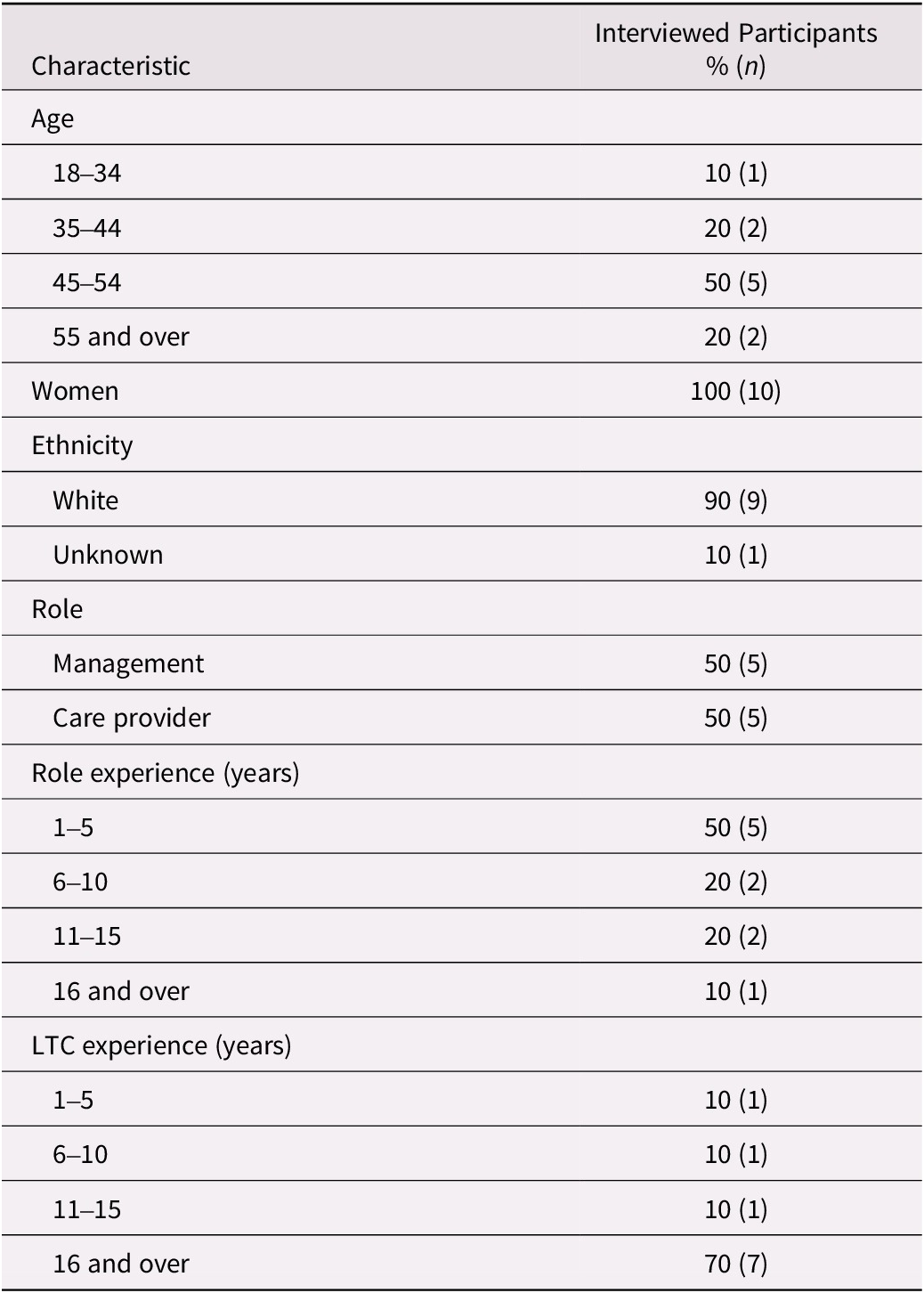

Ten participants, including the NP, were interviewed after 4 months of experience with the huddles. A majority of the participants identified as white women who were between the ages of 45 and 54 years and had 6 to 15 years of work experience in LTCH. Participant demographics are summarized in Table 2. Overall, they spoke favourably of the huddles’ components and strategies included in the toolkit (i.e., design quality). The participants also identified limitations and offered recommendations for making them an effective routine practice in the LTCH.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of interviewed participants (n = 10)

Note: Management included CEO, Administrator, Director of Care, Assistant Director of Care, Quality Assurance and Risk Management Lead.

Care provider includes NP, RPN, and PSW.

Design quality

The staff presented a positive view towards huddles’ components and strategies. The whiteboard and the OFI cards were particularly embraced by the interviewees. The NP described their experience, I think the boards worked; the cards worked. These materials provided the staff with an opportunity to suggest topics for discussion or identify areas for improvement and post them on the whiteboards for others to see. As one registered practical nurse (RPN) explained it, …when I get back to the unit there is a new question or a new suggestion on [the whiteboard], and I’m like, Okay, well that’s good. [The OFI card] gives people a place to put down their ideas or their questions. This also meant that all staff, including individuals who were not able to attend the huddles due to their work schedule, were able to provide input, …especially when it’s [huddle] two days a week and there’s different shifts. They can put their comments on there and see a response when they come in the next night, as explained by the assistant director of care. The ability to complete OFI cards anonymously was also noted as a benefit. The whiteboards were perceived as being useful for quickly disseminating information and engaging all staff in brainstorming – a personal support worker (PSW) describes: Other people, another shift might come up with an idea that you couldn’t fathom. So, it’s sort of bigger. Having the board visible ensured that the topics brought up at the huddles remained relevant, as another RPN reflected: You look at [the whiteboard] and it stays in your head, and you think. The whiteboards also provided a visualization of progress, and this was associated with positive feelings of accomplishment when items were resolved, although one PSW noted, Some things I think will always be on the board because they’re just not an easy fix…I think some things just won’t be fixed. Having the huddle guides accessible proved useful, particularly in two instances when the NP was not available and the huddle was facilitated by another employee in the home, who reflected on leading a huddle: I would just kind of go by the script that was set up … it makes it easy that way, and it doesn’t mean one person is assigned to [facilitate huddles] all the time.

Limitations

In terms of limitations, interviewees discussed difficulty finding a perfect time that would permit all staff to participate in the huddles: It doesn’t always work that our program staff can be available at shift change at 2 o’clock in the afternoon, which is a prime time for huddles, but it’s also right in the middle of their large group activity programs. In addition, workload and staffing shortages were most commonly identified as barriers to participation. An RPN described their experience as, kind of stealing the time from your day. Because you only have so much time for so many residents. Since huddles were introduced on two units only, the NP was described as a scarce resource, as the administrative team expressed their wishes of having a full-time NP as an employee of the LTCH. Additional challenges with remaining within the allocated time were mentioned by some interviewees. Discussing the frequency of huddles, interviewees mentioned that having huddles 5 days a week was too much, because every day not everything changes, as explained by a PSW. Instead, huddles conducted twice a week were preferred by the staff; an RPN described the process as, The first time in the week, this is what was put on the round table. And then the second time, Okay, we’re giving you the feedback to what was discussed. This alludes to the fact that there were no new issues to be discussed when huddles were held daily.

Recommendations

The most common recommendations to improve huddles included increasing the presence of managers, which was recognized by both management and the staff. Recommendations varied from having managers present at huddles at least once a week or having managers floating around, to a more intermittent presence: I think if management is part of solving the problem … yes, they should be [at the huddle]. But if it’s just the routine things that we can solve ourselves, they shouldn’t be there. Nonetheless, despite a lack of agreement on the frequency of managers’ engagement, interviewees agreed that their presence would provide the staff with support and recognition for their work, as one RPN stated: It would be really beneficial just to show the staff that [managers] are here. Participants also made recommendations to compensate for the NP’s limited availability. One solution included training and mentoring an individual on each unit, who would then assume responsibility for future huddles: Each of the units would then have a person and it wouldn’t matter about necessarily their title or their position. Sharing responsibilities for huddles between all staff on the unit was proposed as another solution: …you could do that, and nobody feels left out and nobody is in charge because there are some people that tend to dominate things. Additional recommendations made by interviewees included setting a timer to keep huddles within the 15-minute time limit and maintaining a consistent schedule to ensure that huddles become part of their daily routine.

Discussion

A toolkit that can be used by NPs and other leaders to implement huddles in the LTCH was developed. The toolkit was co-designed with LTCH stakeholders, using the CBPR approach, to be applicable to the LTC context and was used to implement huddles on two units over 4 months. The CBPR approach to designing the toolkit ensured the integration of feedback from end users. Interviews with huddle participants suggest that the toolkit’s components were well received and used. Challenges with dedicating time to huddles were discussed in the interviews, and participants made recommendations for improvements.

Our findings suggest that LTCH employees are open and willing to implement huddles, using the resources provided in the toolkit. This study also found the huddles effective in enhancing communication and practice among LTCH staff. Resources used to visualize and track huddle discussions, such as whiteboards and OFI cards, were particularly important as they provided the staff with opportunities to suggest topics for future huddles, engage in discussions, and contribute to problem-solving, even when they were not able to attend the huddles. Considering huddles were held twice a week (reduced from daily, based on the staff’s feedback), thus limiting attendance based on work schedules, the whiteboard ensured that all staff were aware of the discussions happening in the huddles, a challenge previously described when introducing LTC huddles (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Huijbregts, Sokoloff, Wisniewski, Walsh and Feldman2014). Care staff, such as PSWs and others, provide the majority of care to LTC residents and usually gain a strong understanding of the residents’ personal preferences, behaviours, and best approaches to care (De Witt Jansen et al., Reference De Witt Jansen, Brazil, Passmore, Buchanan, Maxwell and McIlfatrick2017). However, there are often limited opportunities for the staff to contribute to resident care discussions and share their observations and knowledge with their colleagues (Kolanowski, Van Haitsma, Penrod, Mogle, & Yevchak, Reference Kolanowski, Van Haitsma, Penrod, Mogle and Yevchak2015), which can affect their morale and ability to optimize person-centred care (McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, Dewing, Breslin, Coyne-Nevin, Kennedy and Manning2010). Having information about the residents’ personhood as well as strategies useful for mitigating responsive behaviours is necessary for the provision of person-centred care (Kolanowski et al., Reference Kolanowski, Van Haitsma, Penrod, Mogle and Yevchak2015), and huddles can provide opportunities for care staff to share critical knowledge about the residents with other staff, especially those who are new to the team or work casually. Thus, huddles can be an effective strategy to quickly disseminate resident-specific information while increasing the confidence of care staff and their sense of belonging to the team, thereby improving staff-centred outcomes.

Staffing shortages and time-pressured work patterns are frequently raised as challenges in the LTC sector. Participants described time constraints and workload as barriers to participation in huddles. Nonetheless, information disseminated through huddles may save time, as the staff avoid resorting to trial and error, which they experience when providing care to residents, with which they are unfamiliar (Kolanowski et al., Reference Kolanowski, Van Haitsma, Penrod, Mogle and Yevchak2015). Given that the use of agency staff is quite common in LTCH, huddles can be effective in discussing specific strategies that worked for certain residents and should be explored in future clinical and research initiatives. Interviewees perceived having daily huddles as unnecessary, which can be attributed to excessive workloads, charting requirements, and staffing shortages. In this study, huddles were held twice a week, where participants used the first huddle as an opportunity to discuss new approaches to care and the second huddle for follow-up and debriefing. However, other LTCHs may implement huddles at different frequencies based on staff needs and context requirements, such as staffing, team morale, or residents’ medical complexity and changes in health status.

Participants also voiced their desire to increase managers’ presence in the huddles. LTC managers play an important role in influencing resident care and work culture (Siegel et al., Reference Siegel, Bakerjian and Zysberg2018). However, during COVID-19, LTCH administrators were faced with unprecedented challenges, workload, and burnout (Savage et al., Reference Savage, Young, Titley, Thorne, Spiers and Estabrooks2022; White et al., Reference White, Wetle, Reddy and Baier2021). An increase in administrative work may have compromised LTC managers’ ability to be present and visible to staff, prompting interviewees to comment on their absence when they were perceived to be needed the most. Poor communication between management and staff can influence the staff’s ability to work under challenging circumstances (White et al., Reference White, Wetle, Reddy and Baier2021). An investigation of LTC managers’ communication styles during COVID-19 revealed that higher quality of communication, as perceived by the staff, was associated with a better sense of preparedness to care for residents and reduced resignations among staff (Cimarolli et al., Reference Cimarolli, Bryant, Falzarano and Stone2021). Increasing leaders’ engagement with frontline staff can also promote a culture of safety through the identification of unsafe situations (Van Dusseldorp, Waal, Hamers, Westert, & Schoonhoven, Reference Van Dusseldorp, Waal, Hamers, Westert and Schoonhoven2016). As such, LTC administrators and managers can use huddles to demonstrate their support of care staff, as well as contribute to discussions that require their input. Further research is needed to investigate best approaches for leadership involvement.

In this study, one NP served as the intervention champion and facilitated implementation huddles in two units of an LTCH. The NP served in the role of a consultant and may not have been perceived by the staff as part of the management team, which may have positively influenced their openness to participation. Although the toolkit was designed for use by NPs, not all LTCHs have an NP or employ an NP in a capacity to lead huddles. Nonetheless, the toolkit is designed to support all champions as they implement huddles in these settings. The role of the huddle facilitator should be carefully considered. Facilitators with status differences, such as physicians or managers, may impede open communication (Rodriguez, Meredith, Hamilton, Yano, & Rubenstein, Reference Rodriguez, Meredith, Hamilton, Yano and Rubenstein2015). Empowering staff to lead huddles in their units and providing them with resources to escalate issues efficiently and effectively may be one solution moving forward. Engaged administrators and managers can aid staff in implementing and sustaining new practices (Lampman et al., Reference Lampman, Chandrasekaran, Branda, Tumerman, Ward and Staats2021). To spread and sustain huddles, NPs can use the toolkit to enable LTCH staff to lead their huddles.

This study has several limitations. First, the toolkit was designed to address the needs of one LTCH, and thus the topics covered in the guides may need to be modified for the context of other LTCHs. Nonetheless, the components provided in the toolkit can be used to introduce huddles in other homes and as a guide that can be adapted to each unique issue and setting. Second, the NP leading huddle implementation in this study had a unique relationship with the staff of the LTCH, which may have influenced their openness and willingness to participate in the huddles. Furthermore, many LTC homes do not have access to NPs. Although the toolkit was co-designed with NPs as the champions, other LTCH leaders, such as the director of care or charge nurses, may utilize the toolkit to introduce huddles in their LTCH. Finally, the interviewed staff were primarily white with many years of experience in LTCH, which may not be representative of staffing in other LTCHs.

The findings of this study suggest that LTC NPs and other champions can use or adapt this toolkit to implement huddles in their LTCHs. NPs can efficiently implement huddles in LTC; however, input from staff participating in huddles must always be considered when determining dose, frequency, and content delivered. In this study, care staff effectively engaged with the components provided in the toolkit to suggest topics and participate in discussions. Further research is required to investigate sustainability of such huddles, particularly in relation to limitations in NP availability and their other role responsibilities.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the nurse practitioners and the LTCH employees for their expertise in the creation of the toolkit and for dedicating their time to the project during the pandemic. We would also like to thank Ellen Snowball for the design of the toolkit.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Foundation for Health Improvement (CFHI), Canadian Institute of Health Sciences (CIHR), and the Canadian Centre for Aging & Brain Health Innovation (CABHI): Implementation Science Teams: Supporting Pandemic Preparedness in Long-Term Care Funding Opportunity [SPP – 174086]; and by the Walter & Maria Schroeder Institute for Brain Innovation and Recovery Foundation [to KM and JB].