Introduction

The study of candidates in Canadian elections focuses for the most part on aggregate voting patterns and party leaders (Bittner, Reference Bittner2011; Sevi, Reference Sevi2021). The impact of local candidates has largely been overlooked on the grounds that most constituents do not know or care about their local candidates. There have been a few studies showing that local candidates matter, as they make a small but discernible difference in electoral outcomes (Allen Stevens et al., Reference Allen Stevens, Islam, de Geus, Goldberg, McAndrews, Mierke-Zatwarnicki, Loewen and Rubenson2019; Blais et al., Reference Blais, Gidengil, Dobrzynska, Nevitte and Nadeau2003; Blais and Daoust, Reference Blais and Daoust2017; Roy and Alcantara, Reference Roy and Alcantara2015). These studies, however, tend to draw on individual elections; we thus lack a wider picture of local candidates’ influence across elections.

In this research note, we replicate Blais et al.'s (Reference Blais, Gidengil, Dobrzynska, Nevitte and Nadeau2003) article, which found that a preference for a local candidate was a decisive consideration for about 5 per cent of voters in the 2000 Canadian federal election. In what follows, we reproduce the same analysis used by Blais et al. (Reference Blais, Gidengil, Dobrzynska, Nevitte and Nadeau2003) across four Canadian federal elections: 2000, 2004, 2006 and 2008.Footnote 1

Data

Our replication effort is twofold: we replicate Blais et al.'s (Reference Blais, Gidengil, Dobrzynska, Nevitte and Nadeau2003) original analyses for the 2000 Canadian election and we extend them to encompass three additional elections. Like Blais et al. (Reference Blais, Gidengil, Dobrzynska, Nevitte and Nadeau2003), we use the Canadian Election Study (CES) to examine how local candidates affect vote choice, and we run separate models for respondents in Quebec and outside Quebec, as the latter cannot vote for the Bloc Québécois. Our analyses focus on respondents who voted in each election.

Two survey items pertaining to local candidates were included in the CES between 2000 and 2008. Respondents were first asked the following question: “Now the local candidates in your riding. Was there a candidate in your riding you particularly liked?” Those who answered in the affirmative were then asked, “Which party was the candidate you liked from?”

Table 1 shows the percentage of respondents who said they liked a candidate in their riding. The distribution for 2000 is very similar to that reported by Blais et al. (Reference Blais, Gidengil, Dobrzynska, Nevitte and Nadeau2003), but there is more variation in preferences for local candidates in subsequent elections.Footnote 2 In all four elections, this percentage is higher outside Quebec than in Quebec. Among those who voted, the pattern is similar, with slightly more citizens indicating a preference for a local candidate. This suggests that in each election, about half of voters care about their local candidates while the other half do not.

Table 1. Percentage of Respondents and Voters Who Liked a Candidate in Their Riding

Results

Following Blais et al. (Reference Blais, Gidengil, Dobrzynska, Nevitte and Nadeau2003), we first ascertain the independent effect of having a preference for a local candidate on vote choice.Footnote 3 We control for party identification (“Which party do you feel closest to?”) and feeling thermometer evaluations for all parties and leaders (rescaled to range from 0 to 1).Footnote 4 These are the same controls used in the original study. It is crucial to account for these confounders when ascertaining the independent impact of local candidates on vote choice, as each of these variables has its own impact on the outcome of interest. We run two models for each election: one for respondents outside Quebec and the other for those in Quebec. For the first set of models, we control for the region (Ontario, Atlantic, West), as Blais et al. (Reference Blais, Gidengil, Dobrzynska, Nevitte and Nadeau2003) do.

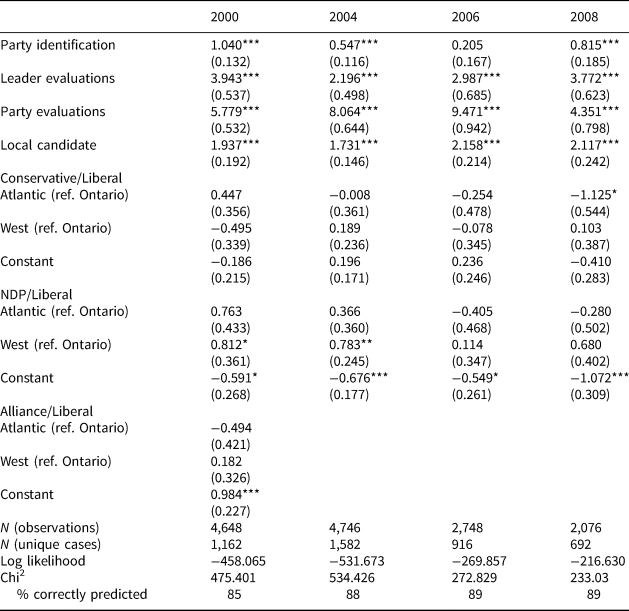

The results are presented in Table 2 (outside Quebec) and Table 3 (Quebec).Footnote 5 The findings are easy to summarize. In both tables, the local candidate coefficient is positive and significant in all four elections, meaning that even after controlling for party identification and feelings toward leaders and parties, local candidates have an independent impact on vote choice. However, the local candidate coefficient is smaller than those for party identification and party and leader evaluations. This is consistent with Blais et al.'s (Reference Blais, Gidengil, Dobrzynska, Nevitte and Nadeau2003) results for the 2000 election. While having a preference for a local candidate does matter, it matters less than partisan predispositions and attitudes toward parties and leaders. All in all, these findings confirm previous work showing that local candidates have a noticeable effect on vote choice.

Table 2. The Impact of Liking a Local Candidate on Vote Choice outside Quebec

Note: Multinomial logit regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. The reference category for vote choice is Liberal. The reference category for region is Ontario.

* p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Table 3. The Impact of Liking a Local Candidate on Vote Choice in Quebec

Note: Multinomial logit regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. The reference category for vote choice is Liberal.

* p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

We now turn to the question of how much local candidates matter. We first estimate each individual's predicted likelihood of voting for each party with all the variables at their observed values. We then estimate new predicted likelihoods in a counterfactual scenario in which we set the coefficient for the local candidate at zero while keeping every other variable in the model constant. We finally compare the predicted vote (that is, the party that has the highest predicted probability of being supported by each individual) under both scenarios. When the predicted vote remains the same for a given individual, it means that local candidates do not matter, as our model predicts that the individual in question would vote the same regardless of her local candidates. When the prediction differs, we infer that the local candidate is a decisive consideration, since the person is predicted to have voted differently if she had not cared about her local candidates.

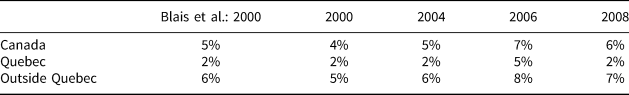

Table 4 reports these predictions for each election, both in Quebec and outside Quebec, as well as in Canada as a whole. Outside Quebec, the local candidate was decisive for 5 per cent of voters in 2000, 6 per cent in 2004, 8 per cent in 2006, and 7 per cent in 2008. In Quebec, only 2 per cent of voters are swayed by their local candidate in the 2000, 2004 and 2008 elections, with 2006 emerging as an outlier with 5 per cent. These results illustrate the relative stability of local candidate effects across the four elections under study. There might be an upward trend for voters outside Quebec, but overall the magnitude of these effects remains very similar across all elections when we examine the country as a whole. These results confirm that local candidates play a real but limited role in federal elections.

Table 4. Percentage of Voters for Whom the Local Candidate Was a Decisive Consideration

Conclusion

We ascertain the influence that local candidates play in Canadian federal elections. Using the CES from 2000 to 2008, we replicate Blais et al.'s (Reference Blais, Gidengil, Dobrzynska, Nevitte and Nadeau2003) original findings and extend their analysis to include four elections in total. We find that local candidates matter consistently for about 5 per cent of Canadian voters. We also confirm one of Blais et al.'s (Reference Blais, Gidengil, Dobrzynska, Nevitte and Nadeau2003) key findings, namely that local candidates matter mostly outside Quebec. We note that local candidates’ significant effect on vote choice is consistent with the argument that first-past-the-post electoral systems allow for the representation of local and regional interests, especially in comparison to systems with proportional representation (Blais, Reference Blais2008).

While this replication focused on elections held during the 2000s, we have no reason to believe that our findings are specific to that period. More recent work on local candidates (Allen Stevens et al., Reference Allen Stevens, Islam, de Geus, Goldberg, McAndrews, Mierke-Zatwarnicki, Loewen and Rubenson2019; Blais and Daoust, Reference Blais and Daoust2017; Roy and Alcantara, Reference Roy and Alcantara2015) reports effects of similar magnitude as ours. Future work should aim to explain what type of local candidates voters prefer.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S000842392200004X.