Introduction

The “age of secession” (Griffiths, Reference Griffiths2016) has been accompanied by an increase in electoral events linked to territorial demands. Secessionism is a peculiar form of territorial demand that can lead to violence both from counter-secessionist and secessionist actors. The destabilizing potential of this phenomenon makes relevant our attempts to better understand its causes and repertory of action. The literature on independence referendums generally focuses on outcomes (LeDuc, Reference LeDuc2003; Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2014a, Reference Qvortrup2014b; Oklopcic, Reference Oklopcic2012; Lee and Ginty, Reference Lee and Ginty2012), with just a few studies analyzing the strategic use of secession referendums and its normative implications (Kelle and Sienknecht, Reference Kelle and Sienknecht2020; Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2020; Cortés-Rivera, Reference Cortés-Rivera2020).

Plebiscitarianism frames independence referendums as a direct democracy mechanism: an expression of the “will of the people.” That is, referendums are called as a device to decide on independence. In a sense, this view is accurate, since these electoral events are generally labelled as independence referendums by media, governments and movements and are portrayed as popular decisions. However, the approach has both normative and empirical flaws.Footnote 1 This article claims that a majority of independence referendums do not have an electoral objective but, rather, a strategic one. In this, they are similar to other types of referendums: “Governments rarely call referendums merely to promote deliberation” (LeDuc, Reference LeDuc2015: 140). This aspect, common to other democratic mechanisms, is even more relevant in the case of territorial referendums. In fact, I claim that few independence referendums are called to decide on independence. Most do not decide on independence but instead provide a source of legitimacy, either ex ante or ex post, for successful (or failed) secession processes (Carboni, Reference Carboni2018). Therefore, I suggest that focusing on the strategic functions of independence referendums is at least as relevant as analyzing their potential moral or legal value (Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2020; Cortés-Rivera, Reference Cortés-Rivera2020).Footnote 2

In order to analyze referendums’ strategic function, I use a dataset of 93 referendums of independence held since 1945. I find that, more often than not, independence referendums have a strategic function. In order to classify and distinguish the strategic function of these referendums, I propose a typology based on two criteria: degree of consensus among actors and timing gradation. Additionally, I suggest potential explanations on the use of referendums of independence within the logic of self-determination dynamics and tactics, and I briefly discuss some normative implications of these findings in the field of theories of secession (Beran, Reference Beran1984; Moore, Reference Moore1998).

The article is structured as follows. First, I review the literature on secession and referendums, highlighting the gap I aim to fill with my contribution. Second, I offer a general outlook on independence referendums since 1945; I analyze the existing variety of referendums and propose a typology. Third, I zoom in on the cases of leverage referendums. By leverage referendums, I mean referendums called exclusively by sub-state authorities or movements without consent from central authorities before effective independence. I identify potential uses of these referendums through the analysis of specific cases using Griffiths’ framework on secessionist tactics (Griffiths and Muro, Reference Griffiths and Muro2020). Fourth, in light of the strategic uses described in the typology, I briefly sketch some normative implications.

Theory and Literature

Theories of secession tend to be moral theories on the right to secede, somewhat detached from empirical secession processes (Sanjaume-Calvet, Reference Sanjaume-Calvet2020). There are generally two broad categories of theories, depending on their moral evaluation of the right to secede: primary right theories and last resort right theories. Among primary right theories, plebiscitarian approaches place a high value on independence referendums as secession plebiscitesFootnote 3 (Beran, Reference Beran1984; Moore, Reference Moore1998).

In his seminal work “A Liberal Theory of Secession,” Beran (Reference Beran1984) built a theory on the right to secede based on the following tenets: “Liberalism assumes that normal adults are self-governing choosers [...]. Yet it seems that a commitment to the freedom of self-governing choosers to live in societies that approach as closely as possible to voluntary schemes, requires that the unity of the state itself be voluntary and, therefore, that secession by part of a state be permitted where it is possible. [...] To permit secession only on moral grounds such as oppression or a right to national self-determination, but not on the ground that it is deeply desired and pursued by adequate political action, seems to be incompatible with the arguments from liberty, sovereignty and majority rule” (Beran, Reference Beran1984: 24–25). Other authors, such as Gauthier (Reference Gauthier1994) and Lefkowitz (Reference Lefkowitz2008), developed this plebiscitarian branch within theories of secession along the same lines.

This theory has been represented as a democratic theory of secession, since it places citizens’ will at the centre of its defence of the right to secede. At the same time, it has raised several criticisms and has been accused of being anti-democratic. Obviously, a common caveat related to the right to secede derived from Beran's approach is a potential slippery slope effect toward fragmentation ad infinitum. Buchanan (Reference Buchanan1991) viewed this as an important concern and rejected this normative approach because of its potential erosion of democratic agreements. According to him, the exit option should be more qualified, something reserved for last resort situations (just cause). In this article, I do not follow this line of criticism. I do think that referendums may play a crucial role in secessionist conflicts; however, I aim to critique plebiscitarianism by looking at the actual use of independence referendums since 1945 through an analysis of their strategic functions.

Several referendums seem to accomplish an accessory function to secession processes. The hypothesis developed in this article is that a majority of referendums do not decide on independence but instead provide a source of legitimacy, either ex ante or ex post, to actors involved in the secession process (Carboni, Reference Carboni2018). Therefore, these kinds of referendums must be interpreted in light of Sir Ivor Jennings’ comment on the principle of self-determination: “On the surface it seemed reasonable: let the people decide. It was in fact ridiculous because the people cannot decide until someone decides who are the people” (Jennings, Reference Jennings2011: 56). The normative intuition developed in this article is that, in many cases, referendums invoke “the people” in a highly performative way rather than as an aggregate of preferences to collectively decide on independence. This performative potential allows for a strategic use of referendums as a source of legitimacy specifically in contexts of conflict. This performative function has been recently highlighted by Cortés-Rivera (Reference Cortés-Rivera2020) as “identity mobilizing” and nation-building in itself.

Independence referendums

Referendums on territorial borders can be traced back to the eighteenth century—the time of Atlantic revolutions and expansion of popular sovereignty. During the American Revolution, Massachusetts’ city councils voted on the former British colony's declaration of independence in 1776; fifteen years later, in 1791, the citizens of Avignon decided in a popular vote to separate from papal domains and be annexed to the French Republic. Since then, more than six hundred referendums have been held on sovereignty issues around the world; these include territorial transfers, autonomy arrangements and the creation of new states (Mendez and Germann, Reference Mendez and Germann2018).

If we exclusively focus on secession referendums in which secession is understood as the “process of withdrawal of a territory and its population from an existing state and the creation of a new state on that territory” (Pavković and Radan, Reference Pavković and Radan2007: 1), the list of referendums must be restricted. However, we still find around two hundred cases since the vote held in Massachusetts. Almost a hundred of these have taken place since the Second World War (N = 93), and they became far more common (N = 65) after the fall of the Berlin Wall and disintegration of the USSR (Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2014a).

In spite of the spread of independence referendums and direct democracy, this type of consultation is generally not allowed by existing states, whether democracies or not. This is true not only for independence referendums but for secessions in general. According to Coggins (Reference Coggins2011), “Historically only around half of the states emerging from secession had their home state's consent by the time they entered the system” (446). In many cases, referendums have been preceded by violent conflict, as in Algeria (1962), or by both violent conflict and international mediation, as in East Timor (1999). In Indonesia, President Suharto repeatedly rejected holding a referendum in East Timor, although the former Portuguese colony had been militarily annexed to Indonesia since 1976. Indonesian authorities accepted a referendum only after long negotiations with United Nations (UN) and Portuguese authorities in New York (Alcott et al., Reference Alcott, Smith and Dee2003). In Sudan, the 2011 South Sudan referendum was held only after a long peace process ended a period of two civil wars and after the United States threatened sanctions against the Sudanese government and applied pressure for stability in the region (LeRiche and Arnold, Reference LeRiche and Arnold2013).

From a legal point of view, constitutional provisions or constitutional doctrines open to these types of votes are extremely rare. A few states or unions regulate the use of referendums for self-determination, with the most well known being Liechtenstein, Saint Kitts and Nevis (for the island of Nevis), Ethiopia, the former union of Serbia and Montenegro, and the European Union (Weill, Reference Weill2018). Beyond constitutional law, the UK, regarding Scotland, and Canada, regarding Quebec, developed relevant jurisprudence on this matter. In federations such as Switzerland and India, there exist specific mechanisms for internal enlargement. Generally, most of the constitutions include unity or indivisibility clauses that a priori preclude the possibility of territorial external self-determination (Weill, Reference Weill2018). Paradoxically, since the fall of the Berlin Wall, in order to achieve internationally recognized statehood, the holding of a referendum among the citizens of the affected territory has become almost a conditio sine quan non. The dissolution of the USSR and Yugoslavia was a significant turning point in this regard. Palermo (Reference Palermo, Delledonne and Martinico2019: 268) affirms that since then, “the referendum has become not only the main but often the exclusive means to address sovereignty claims,” in a sort of “constitutional acceleration” context. The former “right to self-determination” used as a legitimation of colonial secession processes has somewhat been replaced by the so-called “right to decide” (Palermo and Kössler, Reference Palermo and Kössler2017: 273). The Badinter Commission,Footnote 4 which was assembled for the conflict in Yugoslavia, used the principle of uti possidetis juris (as you possess under law) for the first time outside the colonial context in order to defend the integrity of the borders of the republics that used to compose Yugoslavia, and it stipulated the use of referendums as a sine qua non condition for gaining international recognition (Pellet, Reference Pellet1992; Kohen, Reference Kohen2006). In fact, in our times, the international community has a tendency to always request referendums when monitoring secession processes, although there is no international law specifically requiring this step (Landi, Reference Landi2020).

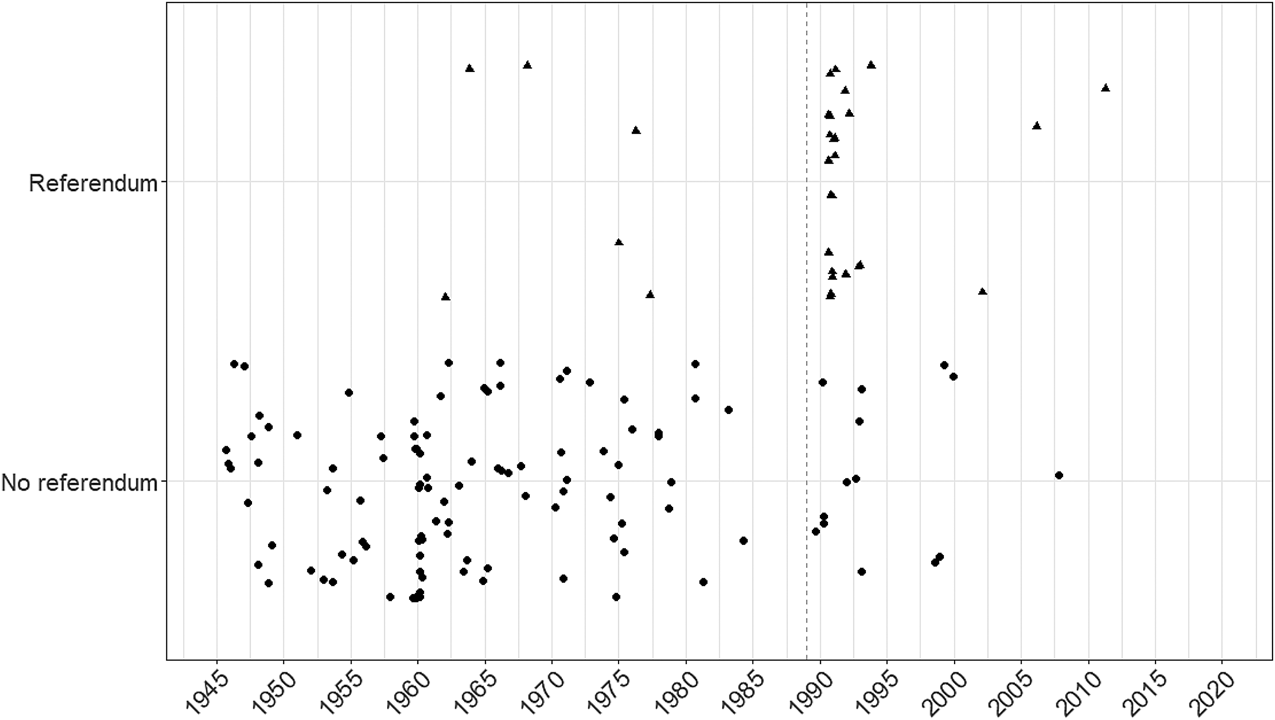

Data on the relationship between entries to the international system and referendums support the idea of the popularization of referendums. Figure 1 shows all entries to the international system, with or without a referendum, since 1945. After 1989, all entries to the international system as a result of secession were supported by an independence referendum, with the sole exception of Kosovo.Footnote 5 Symptomatically, although not entirely for this reason, Kosovo has been recognized by the United States, United Kingdom and France but not by China and Russia and has not been able to become a member of the UN.

Figure 1 Entries to International System with and without Referendum, 1945–2020

Why call for a referendum?

The explanation for why independence referendums are called is an underexplored question. Griffiths and Muro (Reference Griffiths and Muro2020) argue that secessionist movements face a complex strategic field when attempting to achieve their final objective: internationally recognized statehood. According to this approach, secessionist movements simultaneously try to persuade the parent state to give its consent to their objectives (parent states generally oppose secession by default, with more or less aggressive counter-secessionist strategies or constitutional firewalls) and to convince key actors of the international community to support their cause. By key actors, we should read what Coggins (Reference Coggins2011: 433) calls “friends in high places”—that is, permanent members of the Security Council (US, UK, France, Russia and China). Since the rules to access the “club of states” of the UN organization are clear and well known,Footnote 6 convincing the Big Five is a crucial task, especially if the parent state is reluctant to consent to secession. In this strategic playing field, the repertory of action of secessionist movements ranges from violent actions to institutional platforms (Griffiths, Reference Griffiths2020). In practice, achieving statehood is an interaction of effectiveness and recognition (Griffiths, Reference Griffiths2016; Coggins, Reference Coggins2011, Reference Coggins2014). The struggle of these movements normally consists of the double task of raising the costs of non-acquiescence by the parent state and providing normative reasons intended to appeal to the international community, which can either support the cause or put pressure on the parent state.

Evidence suggests that institutions shape actors’ behaviour and choices in the repertory of tactics to achieve the actors’ objectives (Cunningham, Reference Cunningham2014). In the new international context (since 1989) of independence referendums being a conditio sine quan non for achieving statehood, these groups may use referendums simply because they acknowledge that is a direct requirement from the international community. But referendums may also be part of a strategic repertory intended to (a) conquer the hearts and minds (Griffiths and Muro, Reference Griffiths and Muro2020) of the parent state or international community by raising a normative demand on the “right to decide” through a referendum and/or (b) show population allegiance to the secessionist project and thereby raise the costs of significant counter-secessionist measures both at the parent-state and international levels. Kelle and Sienknecht (Reference Kelle and Sienknecht2020), using a dataset on sovereignty referendums (including autonomy referendums), suggest a theory on why sovereignty movements choose referendums as a tool in their repertory of action. According to these authors, referendums, when used by pro-sovereignty movements as leverage, are a tool for showing both capacity and legitimacy to the parent state but also to the international community and to their domestic audience. These authors consider that in democratic contexts, parent-state audience is crucial, while in authoritarian regimes, leverage referendums are directed to obtain recognition from abroad.

Domestic audience has also been explored as a relevant target of independence referendums. Cunningham (Reference Cunningham2014), in a broader study on nonviolent tactics, has shown that outbidding and diversification strategies are relevant to understanding why some leaders call for a referendum. Competition between leaders may be crucial to understanding the need of invoking a popular vote besides international and parent-state audiences. Siroky et al. (Reference Siroky, Mueller and Hechter2016), in a study on regional demands in liberal democracies, precisely portray secessionist movements’ tactics as strategic devices to obtain a better negotiation position. According to these authors, showing a credible threat of exit strengthens the sub-state actors’ position in future negotiations in federal contexts. Cortés-Rivera (Reference Cortés-Rivera2020) lists a number of reasons that explain the strategic use of independence referendums, including popular mobilization, timing control, democratic framing and local identity strengthening. This author concludes that referendums normally provide leverage to secessionist movements, regardless of the circumstances.

A Typology

The literature on independence referendums offers myriad criteria to classify independence referendums. They are generally included in the broader “ideal” category of sovereignty or ethno-national referendums and classified according to legal (not political) criteria. That is, a commonly used typology distinguishes between de facto and de jure referendums; while the former would be held without a legal framework, the latter would have a legal basis (national or international) (Gökhan Şen, Reference Gökhan Şen2015: 62). Other classifications that follow legal criteria include the type of actors initiating the referendum (institutional vs. non-institutional) or kinds of legal basis (constitutional vs. international). From a material but still legalistic perspective, Sussman (Reference Sussman2001) proposes a classification of a broad category of sovereignty referendums according to their function and objective in relationship to the fate of the territory: annexation, up-sizing, downsizing, secession, and so on. Similarly, Gökhan Şen (Reference Gökhan Şen2015: 63–68) proposes a typology of referendums according to their “legal base, subject matter and the historical and political context,” which includes referendums of accession or border, status (decolonization), unification, transfer of sovereignty, subnational territorial modification, and independence. He divides independence referendums between de facto, de jure colonial and de jure non-colonial. Along the same lines, Laponce (Reference Laponce2010) classifies sovereignty referendums according to the status of the affected territory (transfer, union, separation, restricted sovereignty and status quo). Finally, Mendez and Germann (Reference Mendez and Germann2018) have a more elaborated typology of referendums, together with a very complete dataset. These authors combine the logic and scope of sovereignty referendums and obtain a well-designed cartography in which independence referendums are considered as “full scope” and “disintegrative.” Mendez and Germann's typology is probably the most elaborated, encompassing all sovereignty referendums up to date, but is not specifically focused on independence consultations.

From a less legal and more political perspective, Qvortrup (Reference Qvortrup2014a) distinguishes sovereignty referendums according to their sociological function concerning society and cultural diversity. Using this criterion, he defines four types of referendums: international homogenizing (secession), international heterogenizing (right-sizing), national homogenizing (difference-eliminating) and national heterogenizing (difference-managing) (Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2014a: 20). Carboni (Reference Carboni2018) adopts a more political point of view, as well, distinguishing the functions of indirizzo (political direction of future actions) and legittimazione (legitimacy of constitutional change) of independence referendums. Recent publications, such as Kelle and Sienknecht (Reference Kelle and Sienknecht2020) and Qvortrup (Reference Qvortrup2020), specifically focus on the strategic use of referendums to understand their function but do not propose a typology. While Kelle and Sienknecht (Reference Kelle and Sienknecht2020) place the signalling strategic function of referendums in the broad category of secessionist strategies, Qvortrup (Reference Qvortrup2020) adopts Gökhan Şen's (Reference Gökhan Şen2015) legal approach distinguishing between colonial, agreement and unilateral referendums.

To sum up, these typologies may be useful and necessary in many research projects, but they do not inform us about the specific strategic use of referendums and are not specifically focused on independence referendums. The literature reviewed in the preceding paragraphs has proposed typologies of referendums, but most are based on legal or sociological categories, not political functions. And no typology of independence referendums focused on their political and strategic function has been proposed to date in the literature.

Criteria

Following Carboni (Reference Carboni2018), I analyze referendums as legitimacy devices used for various strategic functions in a secession process (Griffiths and Muro's [Reference Griffiths and Muro2020] strategic playing field), as Kelle and Sienknecht (Reference Kelle and Sienknecht2020) suggest. I use an adapted version of Mendez and Germann's (Reference Mendez and Germann2018) definition of referendum. I define an independence referendum as any popular vote on creating a new state (or including this option) organized by the parent state or by a state-like entity or political movement, such as the authorities of a de facto state or a grassroots social organization. My key research question is about the strategic function of obtaining people's consent: How is this consent expressed in the referendum going to be used by those calling it? Are these referendums called to achieve statehood, to affirm it, to negotiate, or to reject it? This strategic approach informs the typology presented in this article. I do not aim to create ideal types of referendums of independence. My typology allows for a fine-grained analysis of the potential strategic uses of referendums of independence in different contextsFootnote 7 that are explored in the next sections; it has a descriptive value, in itself, for understanding referendums in the Weberian sense (verstehen), but it can also be used in further research on secession conflicts, referendums and secessionist tactics to explain (erklären) actors’ behaviours.

Inspired by double criteria typologies of referendums, such as Mendez and Germann (Reference Mendez and Germann2018) and Silagadze and Gherghina (Reference Silagadze and Gherghina2020), I propose classifying referendums of independence using two criteria:

1. Degree of consensus (unilateral/multilateral) among actors on calling the referendum. That is, the referendum may be unilaterally called by the seceding group (through its institutions, parties or civil society) or called as a result of a bilateral or multilateral agreement. Between these two extreme positions, referendums may eventually be multilaterally called by a coalition of actors, but not all of them. For example: the 2017 referendum in Catalonia was called by a coalition of secessionist forces but boycotted by unionist political parties and repressed by central authorities, while the Quebec (1980, 1995) referendums were called by secessionist and pro-autonomy political parties, and Quebecker federalist forces took part in the referendum campaigns (against independence). However, both referendums were called without explicit consent from central authorities. In Catalonia, there was no constitutional basis to call for a referendum, while in Quebec the referendum was already a prerogative of the provincial government.Footnote 8

2. Timing gradation (before or after independence) of the referendum. By timing gradation, I mean that the referendum may be called before or after effectiveness over the territory (de facto and de jure, or just de facto). Sub-state authorities might be de facto effective on their territory because of a dissolution of the parent state or as a result of a violent conflict (or both). Again, this criterion is used as a binary category to build the proposed typology, but in practice it may be regarded as a continuum rather than as a dichotomy. Effectiveness over disputed territories is generally partial and does not always satisfy a clear distinguishing criterion. I consider referendums held “after independence” as cases in which there is a powerful sub-state administration and local paramilitary or military force on the terrain before the vote. Therefore, I code a case (before or after independence) depending on its regional authorities / movement military effectiveness on the territory and/or the effectiveness (or not) of the parent state on the seceding territory.

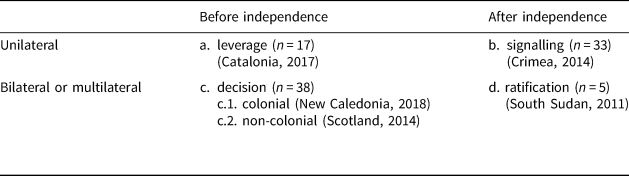

Based on these criteria, I obtain four categories of referendums (see Table 1). In all categories, referendums are used as a source of popular legitimacy. However, the strategic function of this direct democracy mechanism differs. Why these criteria? I claim that actors and timing are the key variables to take into account in order to grasp the strategic function of referendums. Actors’ involvement defines who is taking part in this event, while timing tells us about real power over the territory (that is, who is the sovereign).

Table 1 A Typology of Independence Referendums according to Degree of Consensus and Timing (N = 93)

Dataset

The data presented in this article partially comes from a broader dataset constructed by Mendez and Germann (Reference Mendez and Germann2018). Out of more than six hundred referendums, I select those labelled as independence referendums since 1945 (N = 93), including those held in colonial territories. The dataset begins in 1945 because the strategic playing field of secessionist movements described above as an interaction of effectiveness and recognition established its current international rules since the end of the Second World War and the creation of the UN. In my dataset (see Table 2), I include some variables for the results and date of each case based on secondary literature as well. Using secondary sources, I include two variables: the first regards the actors involved in calling for the vote: unilateral (1-0); while the second regards the moment it was called: timing (0 = before de facto independence; 1 = after de facto independence). Then I include a variable on the outcome of the referendum (0 = status quo; 1 = de facto statehood; 2 = UN membership). Finally, I include variables concerning the political context colonialism (1-0) and geographical context salt-water (1-0).

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics of Referendums Dataset (N = 93)

Four political functions

Reality is always more complex than theory, and borders between the four categories (leverage, signalling, decision, ratification) presented in Table 2 may be questioned. I code actors and timing as rule-of-thumb variables, but in many cases, these criteria are unclear and can be a continuum rather than a binary. For example, in some cases, it is hard to determine if the referendum was held before or after de facto independence (for example, in the case of Eastern European republics in which the parent state was fragile), while in other cases, the distinction between unilateralism and multilateralism is blurred (for example, in Quebec, the referendum was unilaterally called within the scope of provincial powers but tolerated by federal authorities). In any case, I argue that the strategic function of these referendums as a source of legitimacy is different in each category, and all referendums included in the dataset have been classified according to one of the four categories. A definition of each strategic function according to the typology is as follows:

a. Leverage. This type of referendum is generally called by sub-state governments or movements that expect to negotiate with their respective parent state. The main audiences for these referendums are the parent state and the seceding unit's internal audience, although they may also be directed at international community observers. Popular sovereignty as a source of legitimacy is used as a leverage to negotiate with central authorities; this may include a “declaration of independence” or the threat to pass a declaration after the referendum. These referendums may be called against the legal framework (Kosovo, 1991; Catalonia, 2017) or with uncontested legal basis (Quebec, 1980, 1995) and entail a high degree of popular mobilization. Generally, the actors’ priority in calling for these referendums is to make the parent state acquiesce and accept the right to secede (or the right to hold a referendum of independence), but secondary objectives can include internal cohesion and mobilization and international awareness and recognition of the conflict.

b. Signalling. This use of popular vote is generally exercised by de facto authorities in de facto independent regions to legitimate their new status. The main audiences for these referendums are the international community—but not the “former” parent state—and the “new” citizenship under de facto new authorities. These referendums may occur in contexts of parent-state dissolution (USSR, Yugoslavia) or extreme parent-state weakness (for example, Somaliland, 2001). In cases such as Somaliland (2001), Transdniestria (2006) and Crimea (2014), the function of popular votes was not related to any expectation of political negotiation (sovereignty was already exercised by de facto authorities) but to the internal and external validation of a new political status that had previously occurred and was an ongoing, unstoppable process. For example, in Crimea, the March 16, 2014, referendum on Crimean independence and subsequent annexation to the Russian federation was preceded by the decision of the Crimean Supreme Council to separate from Ukraine, which was taken on March 6, 2014. It was also preceded by a military operation supported by Russian forces that took direct control of the peninsular territory (Catala, Reference Catala2015). Former parent-state weakness and some degree of territorial control are crucial to this kind of referendum.

c. Decision. This type of referendum requires a previous agreement between actors from the seceding territory and domestic parent-state actors and/or third-party actors on using the popular vote as a way to decide on the future of a territory through the vote of its population. The main audience of these referendums is the domestic population; the parent-state and international community are not the primary audience, since parent-state consent has already been obtained. There are two types of decision referendums. The first refers to referendums deciding the fate of former colonial powers regarding overseas territories—that is, geographically noncontiguous territories (35 out of 38 cases). In these cases, referendums are normally used as a tool for legitimizing the overseas entities’ political status, sometimes through UN mediation. Currently, there are still 17 territories that remain on the UN list of Non-Self-Governing Territories. The second type of decision referendum refers to non-colonial territories. These cases are a minority (only three cases). In some contexts, these referendums are the result of a post-conflict agreement, such as in Montenegro (2006). In that case, the referendum was supervised and agreed to not only by the parent state but also by international actors (Oklopcic, Reference Oklopcic2012). In other contexts, such as the Scottish referendum on independence (2014), these referendums are the result of domestic ad hoc agreements between parent-state and regional authorities (Cetrà and Harvey, Reference Cetrà and Harvey2018) or previous constitutional clauses (Nevis).

d. Ratification. This kind of referendum is generally foreseen in previous agreements reached by political authorities. In current practice, the referendum is generally used as the end of a peace process in post-conflict contexts. Recent cases in the dataset include East Timor (1999) and South Sudan (2011). These referendums normally seal peace agreements and send an end-of-conflict message to the internal population and to external actors. A historical example beyond the scope of this article is the Norwegian independence referendum held in 1905. In this case, the Swedish government was ready to declare the union with Norway dissolved when the Norwegian Parliament declared the dissolution of the union with Sweden. After an overwhelming majority supported the dissolution in a plebiscite, Swedish authorities officially recognized the independence of the Kingdom of Norway. This process can also be labelled as consensual secession (Buchanan and Moore, Reference Buchanan and Moore2003).

Analysis

In this section, I apply the strategic functions described in the typology to an analysis of independence referendums, regarding their distribution over time, turnout and support for secession, and outcomes.

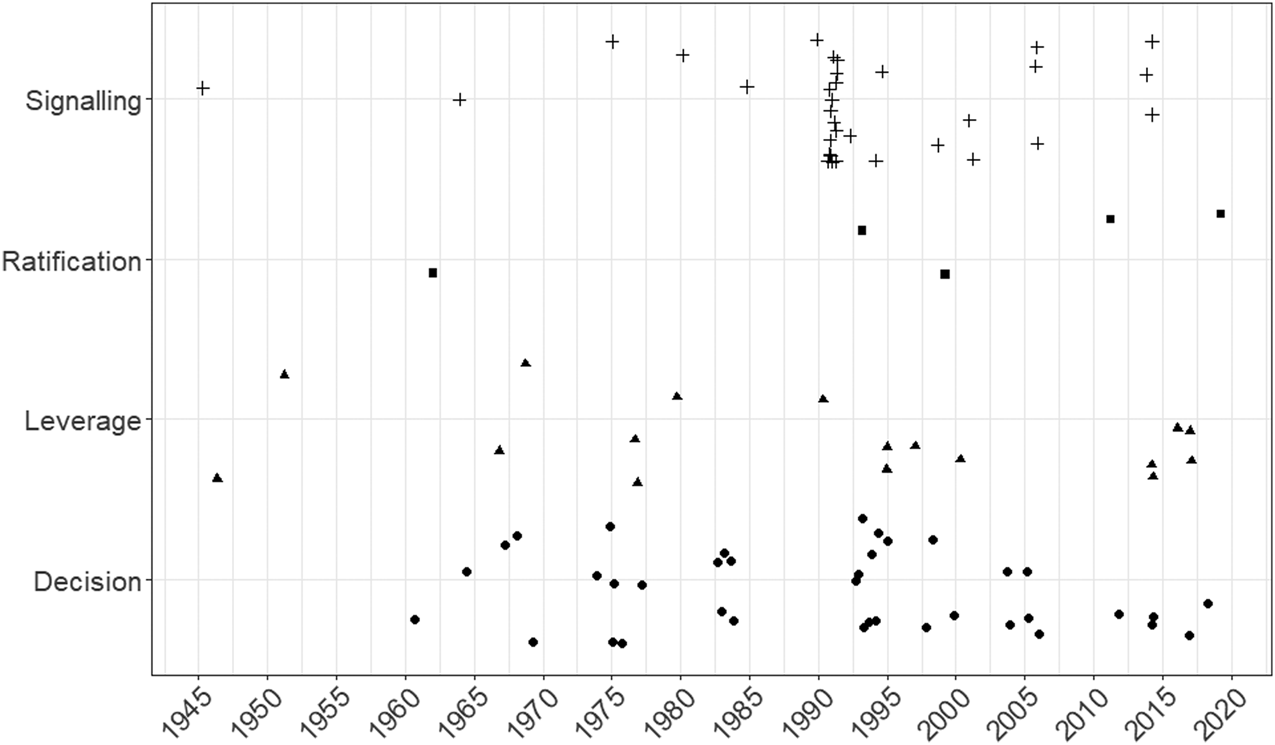

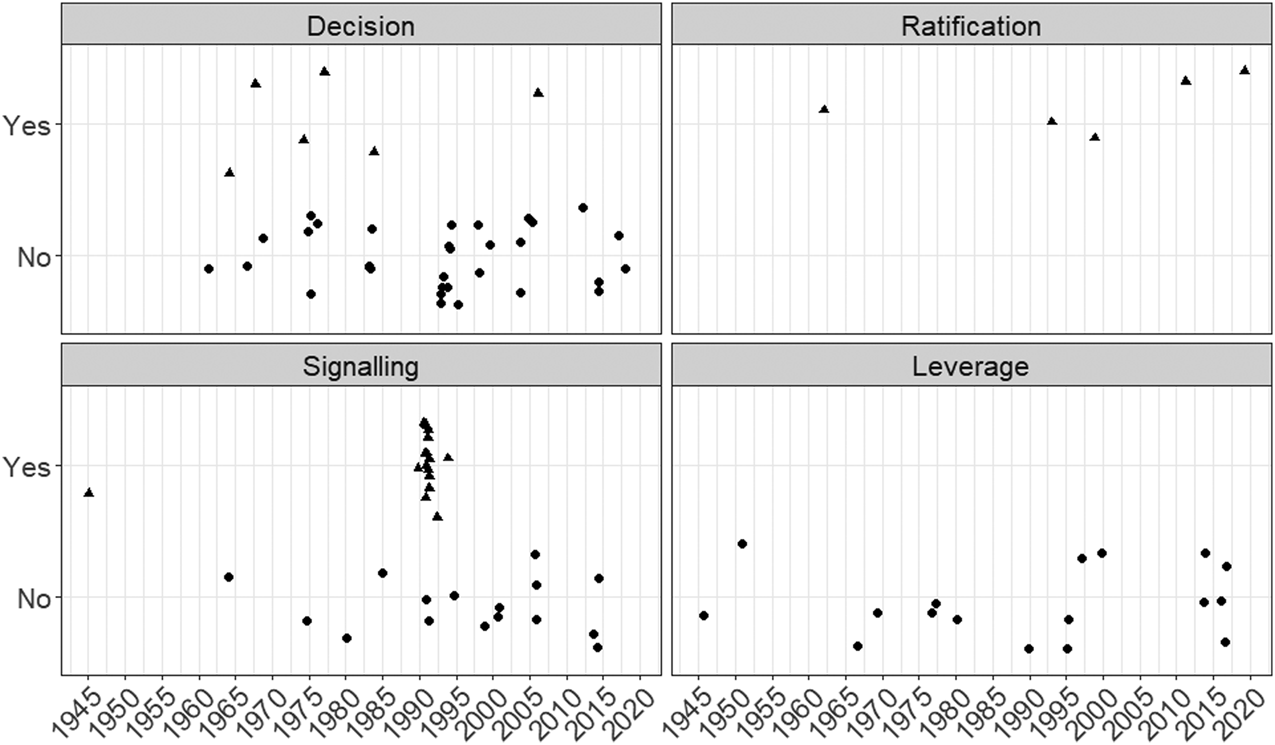

Distribution over time

The proliferation of signalling and leverage referendums since 1989 shows the impact of the change to international rules (see Figure 2). These referendums had been used in the past, but the dissolution of the USSR and Yugoslavia marked a clear turning point, as mentioned in the first section. During the last two decades, there have been 15 independence referendums in contiguous territories (no salt-water), and only 3 of them were non-unilateral (South Sudan, 2011, ratification; Montenegro, 2006, and Scotland, 2014, decision. On the contrary, the other 12 cases were unilateral and did not succeed in creating any internationally recognized state: 7 had a signalling function in de facto independent territories (South Ossetia 2001, 2006; Somaliland, 2001; Transdniestria, 2001; Nagorno-Karabakh, 2006; Crimea, 2014; Donetsk, 2014) and 5 had a leverage function (Catalonia, 2014, 2017; South Tyrol, 2014; South Brazil, 2016; Kurdistan, 2017).

Figure 2 Distribution of Types of Referendums over Time, 1945–2020

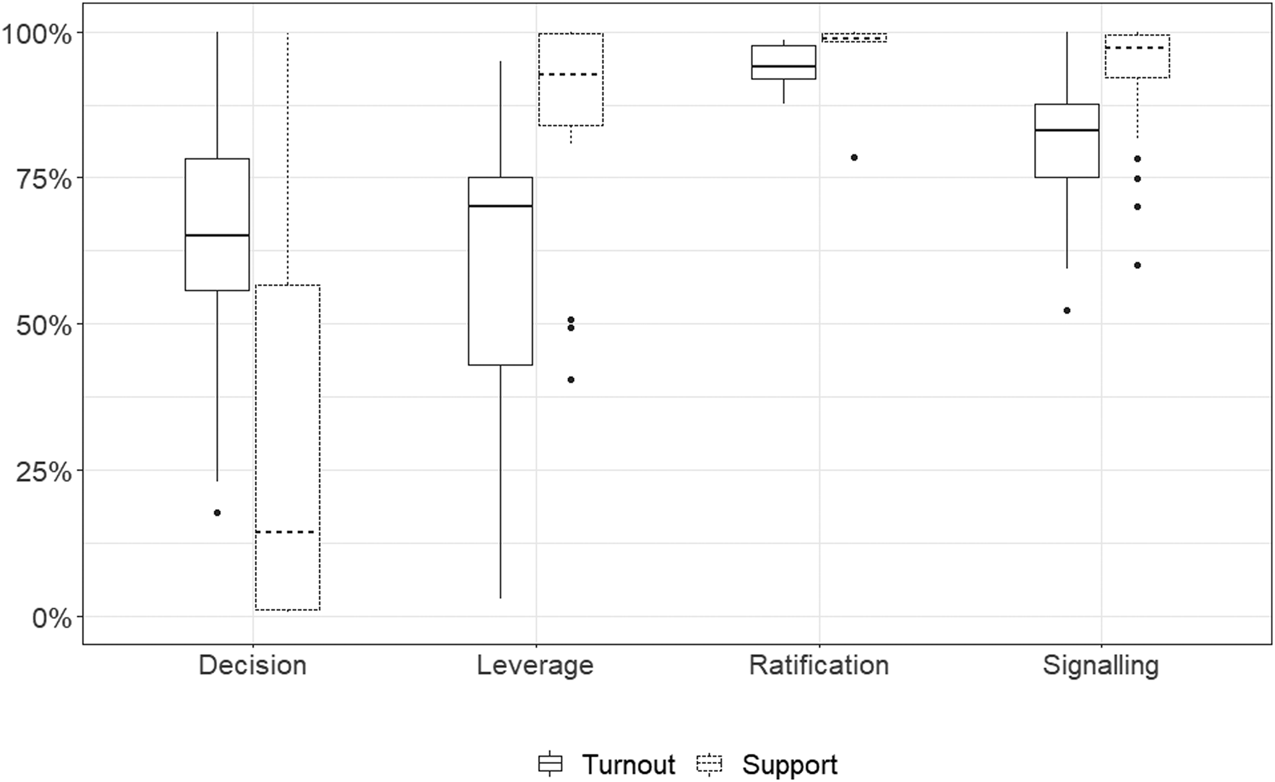

Turnout and support for secession

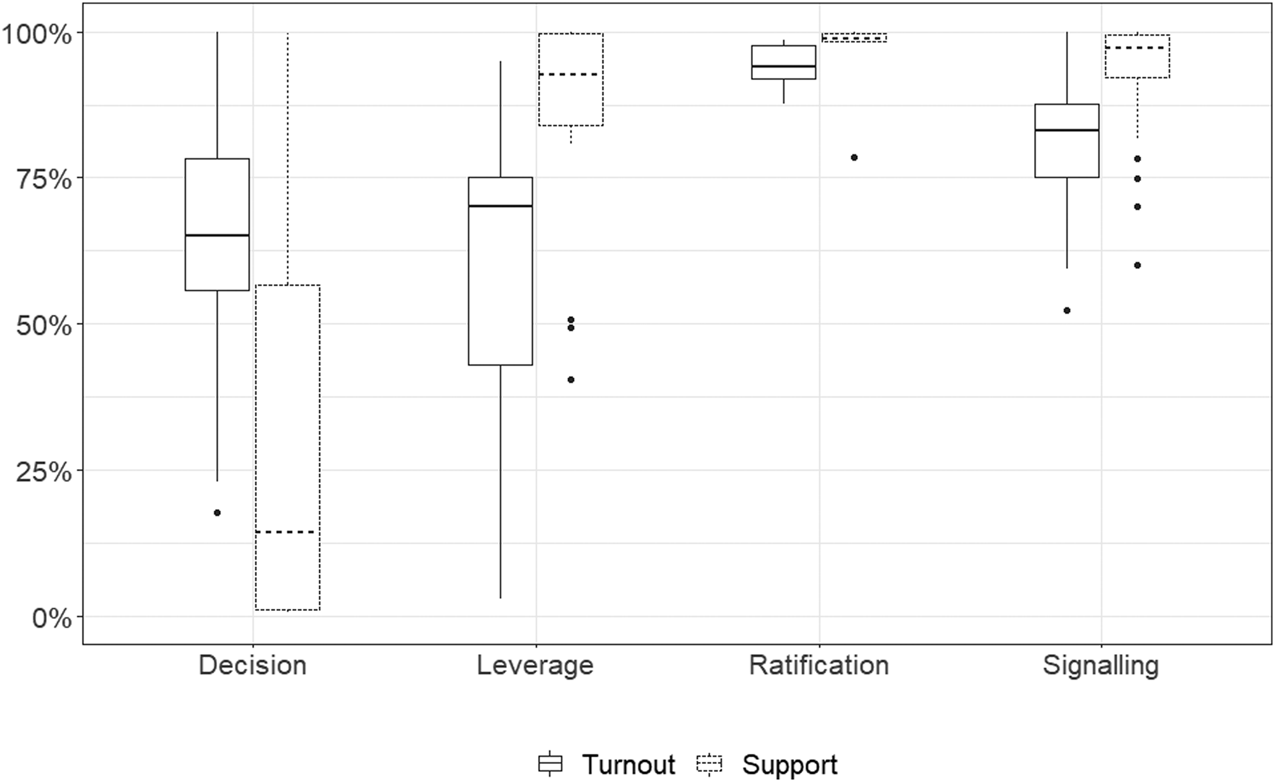

Turnout and support for independence show high variability across types (see Figure 3). Logically, ratification and signalling referendums show high levels of support for secession and turnout. In fact, none of the 76 cases included in these categories voted against independence. Once independence is a fact and the territory is somewhat under control of secessionist authorities, independence referendums either ratify the status quo or signal the existence of an independent authority, depending on the degree of agreement with their respective parent-state government. Leverage referendums show a similar pattern, although in this case, there is a higher variability. In most cases, sub-state authorities calling for an independence referendum obtain overwhelming support for independence, although they often do so with a very low turnout, as in “referendums” called by parties or movements (for example, South Tyrol, 15 per cent; Southern Brazil, 2.9 per cent) or by autonomous regions in decentralized or federal states (for example, Catalonia, 2014, 2017; Kurdistan, 2017).

Figure 3 Turnout and Support of Independence by Type of Referendum

Surprisingly, there were only two cases in which secessionist leaders failed to obtain a majority support for secession, and both were in Quebec (1980, 1995). The Quebec case is somewhat exceptional, since among the 37 cases of leverage referendums, only those held in Quebec were legal (but unilateral at the same time). However, they cannot be labelled as decision referendums according to the typology proposed in the previous section, since these votes were not called consensually with central authorities. In both cases, 1980 and 1995, the question wording included future (hypothetical) negotiations with federal authorities in case of a secessionist victory, and the referendum result was clearly expected to be a leverage tool to negotiate with the central government (at least from the independentist leaders perspective). In any case, Quebec referendums results follow a common pattern of decision referendums: high turnout and low support for secession. Among the decision referendums, few resulted in more than a 50 per cent vote for independence. In fact, a most of these referendums were used by former colonial powers or metropolitan powers (France, Netherlands, United States) in remote territories (islands) to decide on their final status. Nevis (1998), Montenegro (2006) and Scotland (2014) are three exceptions, since they occurred in parent-state territories (contiguous territories) not belonging to former colonial domains. However, only in the case of Montenegro was the outcome an independent state (the referendum was held in May 2006, and Montenegro became the 192nd member state of the UN in June 2006).

Outcomes and leverage referendums

Following the typology, the most interesting kinds of referendums in terms of a secessionist strategy are leverage referendums. In these cases, referendums are used as a tool to achieve independence by sub-state authorities and movements. Unlike in signalling referendums, independence is still far from being a reality on the terrain, because of the opposition of the parent state and the lack of de facto power. Paradoxically, as the literature has suggested, the success rate (that is, achieving internationally recognized statehood) of these referendums is very low: while secession is overwhelmingly supported in these votes (with variable turnout rates), the results are rarely implemented because of parent-state refusal to recognize them. A glimpse at the rate of success in terms of achieving internationally recognized statehood by categories of referendums clarifies this point (see Table 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 4 Success per Type of Referendum and Time

Table 3 Success Rate per Type of Referendum

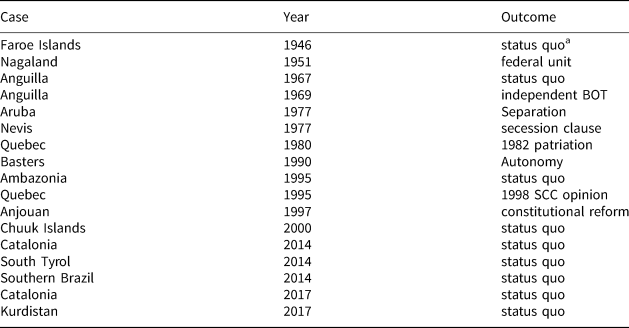

Table 4 shows the complete list of leverage referendums since 1945. These referendums proved extremely unsuccessful in achieving independence, as we have seen. In fact, none of them has served to achieve independence. Probably Anguillan and Aruban cases can be regarded as the most successful, since these territories achieved an independent status within their respective former colonial-power scheme of governance (UK and Netherlands) sometime after holding independence referendums.

Table 4 Leverage Referendums: Outcomes, 1945–2020

a Status quo here means that nothing changes.

Exploring the reasons of the outcomes of these referendums would require a more in-depth analysis of each case that falls beyond the scope of this article. The literature has pointed out several explanations for why secessions do not occur, including psychological factors (Dion, Reference Dion1996) and economic and political variables (Hechter, Reference Hechter1992). Moreover, peaceful secessions are rare and involve a high degree of consensus and a constitutional or legal framework (Young, Reference Young1994). However, with the empirical evidence I have accumulated, I can propose some ideas on the use of independence referendums as a leverage.

First, unilateral independence referendums, when used by sub-state entities without territorial control (de facto independence) do not seem to be useful as a way of achieving independence. That is, no case of leverage referendum has ever led to internationally recognized statehood. However, stating that these kinds of referendums are somewhat useless would be a hasty conclusion. As I show in Table 4, movements or sub-state governments holding these referendums often change their status quo over time. Cases such as Nevis show that popular sovereignty expressions in unilateral referendums may be taken into account in future negotiations over these territories. In this tiny Caribbean island, the referendum held in 1977 resulted in overwhelming support for secession. At the time, the result was ignored and repressed by British authorities. However, later on, when the territory ceased to be under colonial rule together with the island of Saint Kitts, the federal constitution of the new political union respected the right of Nevis to secede.

Second, repression is the most immediate outcome of leverage referendums. In almost all cases, leaders who called for an independence referendum faced serious legal and political consequences, ranging from legal prosecution to military occupation. Exceptions include very low turnout referendums organized as polls by small parties (Southern Brazil, South Tyrol) or referendum results against independence, as in Quebec. In the case of the Faroe Islands (1946), electoral results after the referendum vote, which was in favour of independence, did not support the pro-independence mandate of the referendum. However, Danish authorities dissolved the Faroese institutions and declared void the referendum result.

Third, some cases show a more complex balance in terms of costs and benefits for secessionist movements unilaterally calling for independence referendums. The experience of Quebec has inspired some reflections on the right to secede. There is a common perception that in spite of the quality of the Supreme Court ruling of 1998 on Quebec secession,Footnote 9 the results of the 1980 and 1995 referendums have not been favourable to the interests of Quebec secessionists. This conclusion is related not only to the referendums’ results—both rejected the secessionist option—but to the Canadian constitutional response to the referendums. In the 1980s, the referendum result was part of the reason for the 1982 Constitution, and the Quebec government deciding not to “sign on” to the 1982 constitutional package fuelled two rounds of failed constitutional reform negotiations. Indeed, Brian Mulroney ran for prime minister in 1984 on the promise of bringing Quebec back into the constitutional family. The failure of these accords, more so the Meech Lake Accord, led to increased support for independence, which led to a Parti Québécois electoral victory in 1994 and then the 1995 referendum.Footnote 10 The second referendum, in 1995, did not open a constitutional reform, but it generated a harsh debate on the right to secede that finally translated into the well-known 1998 Supreme Court opinion and the Clarity Act.Footnote 11 Regarded as leverage referendums, both experiences gave Quebec an enormous salience and a unique asymmetry in comparative terms. However, they also reinforced the Canadian constitutional system in terms of federal “patriotism” and established significant hurdles for future secessionist attempts (Rocher, Reference Rocher2014).

Discussion

The analysis presented in this article shows some aspects that secession theories should take into account. First, the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 precipitated a major change in the rules of the game for accessing internationally recognized statehood. Democracy became a relevant part of accessing statehood, and holding a referendum became almost a norm. Beran's (Reference Beran1984) theory may be regarded, at least from this historical perspective, as a successful normative proposal avant la lettre.Footnote 12 However, this does not mean that decision referendums increased after 1989. On the contrary, according to the typology proposed in this article, signalling and leverage referendums became more fashionable than ever. The USSR and Yugoslavia dissolution popularized the use of referendums in regime change contexts, and later on, signalling and leverage referendums were almost universally used by secessionist movements.

Thus, the second aspect derived from this empirical outlook is that referendums may look like a device to decide on secession, but they aren't most of the time. Few actually serve the purpose derived from this normative theorization. Besides decision referendums, the other three categories in the typology do not obey this objective. The unanimity shown by the electorate voting in these referendums is somewhat conclusive: in most of these cases, majorities in favour of seceding are overwhelming—even close to 100 per cent. Within the category of decision referendums, one might think that independence is actually at stake in these cases. However, this is not exact, since 35 out of a total of 38 cases correspond to former colonial territories or overseas territories in which “independence” appears on the ballot generally mixed with other intermediate options, such as associations or different overseas status (depending on the former colonial power). Therefore, sensu stricto according to the data presented in this article, only the cases of Nevis (Reference Palermo and Kössler1998), Montenegro (2006) and Scotland (2014) meet the normative idea of “deciding over independence,” as plebiscitarian theories suggest.

When allowed by parent states, independence referendums seem to be a tool of managing a territorial political status in which independence is an option but not the most preferred option. This fact may explain the difference between turnout and support for secession as being mainly a selection effect.Footnote 13 Central governments and non-secessionist actors allow or participate in these referendums when independence is expected to be defeated at the ballot box. Besides these cases, referendums may be used as a ratification device of internationally sponsored political agreements in post-conflict cases (in which independence was decided in the battlefield rather than in the ratification vote). On the contrary, when referendums are used by secessionist movements generally, either look for proof of popular support (in many cases, overwhelmingly in favour of secession) or ratification of de facto authority (effectiveness) over the territory. Plebiscitarianism is more a performative ideal to legitimate strategic functions within the secessionist playing field than a democratic theory of secession.

So when are decisions on independence left to the electorate? Is plebiscitarianism possible in a secessionist conflict? One can reasonably speculate that this may happen (as in the cases of Nevis, Montenegro and Scotland) (a) only in non-performative contexts—that is, when “who is the people” is not the contest and (b) when both when the parent state and the seceding territory authorities expect to win the vote. In Scotland (2014), the odds of independence winning the vote were very low when Prime Minister David Cameron reached an agreement with Scottish authorities. In Nevis (1998) and Montenegro (2006), in radically different contexts, constitutional rules and political agreements raised the bar for qualified majorities requirements, making plebiscitarianism easier to digest for central authorities. In both cases, voters preferred independence, but in Nevis, support for breaking up did not reach the two-thirds majority, while in Montenegro, it slightly surpassed the 55 per cent threshold.

Conclusions

The typology presented in this article describes four different strategic functions of independence referendums since 1945: leverage, signalling, decision and ratification. In spite of the universal requirement of independence referendums to access statehood since 1989, realpolitik and not the ballot box decides issues of secession (Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2020). The description of independence referendums through the lens of this typology shows that the ballot box is rarely used as a decision mechanism but that it is used as a strategic one. Political functions of independence referendums generally obey a strategic and performative function in the larger picture of a secessionist conflict. This conclusion is consistent with previous literature on this topic (Cortés-Rivera, Reference Cortés-Rivera2020; Kelle & Sienknecht, Reference Kelle and Sienknecht2020; Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup2020).

On the one hand, referendums, when unilaterally used by secessionist authorities or movements, are either a leverage tool to force the parent state to acquiesce or a mechanism to signal the existence of a de facto independent territory to the international community (and the former parent state). In both cases, results are generally overwhelmingly in favour of seceding, but often they bear no consequences. On the other hand, most of the cases of non-unilateral referendums since 1945 took place in post-colonial contexts or in post-conflict situations. In a nutshell, decision referendums are rare because for this kind of referendum to occur, there needs to be a previous agreement between the parent state and the seceding unit (in which the “who is the people” is established) and expectations to win the vote on both sides. In the typology proposed in this article, even the category of decision referendum contains a majority of referendums in which the break-up option was merely added to the ballot box, without any chance of it being a majority choice. Deciding on secession through referendum can occur, but it's rare. Cases such as Nevis (1998), Montenegro (2006) and Scotland (2014) show both the existence and rarity of this possibility.

These findings have normative implications. The international success of referendums since 1989 is a sweet-and-sour victory for plebiscitarianism. It has not meant a success of the ballot box over realpolitik. International community and sub-state authorities and movements seem to be enthusiasts of independence referendums, while states rarely allow them beyond the function of managing the governance of overseas territories. Democratic secession understood as an independence process decided through referendum is possible but also rare in practice. In fact, more often than not, referendums are used as an accessory source of legitimacy to the ones that already decided who the people are. Plebiscitarian theories of secession, and normative approaches in general, should take this reality into account.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423921000421.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge the comments I received on earlier versions of this article from the participants at the Political Theory Research Group (GRTP) at Universitat Pompeu Fabra and from various anonymous reviewers. All errors are mine.