For over a century, the expectation in Canadian parties has been that party delegates, members or supporters in each riding should pick candidates at local nominating conventions (Carty, Reference Carty and Kenneth2002; Farney and Koop, Reference Farney and Koop2018; Siegfried, Reference Siegfried1906). However, there is mounting evidence that both central party actors (such as party leaders, their staff, or party executive directors) and local party actors (such as riding association executives) exert influence over candidate selection behind the scenes (Cheng and Tavits, Reference Cheng and Tavits2011; Cross, Reference Cross, Pammett and Dornan2006, Reference Cross2016; Cross and Prusyers, Reference Cross and Pruysers2019; Koop and Bittner, Reference Koop and Bittner2011; Marland and DeCillia, Reference Marland and DeCillia2020; Pruysers and Cross, Reference Pruysers and Cross2016; Thomas and Morden, Reference Thomas and Morden2019; Tolley, Reference Tolley2019). Given the evidence that central and local actors can influence the outcomes of candidate selection, Cross (Reference Cross2018) reconceptualizes candidate selection as an area of shared authority rather than local autonomy. While we know that central and local party actors can influence the outcomes of candidate selection through these practices, we know relatively little about why central and local party actors decide to exert influence over local nomination races. Why do central and local party actors engage in gatekeeping in certain nomination races but not others?

In this article, I present a theory of gatekeeping by central and local party actors. This theory provides a synthesis of past findings from Canadian and comparative parties scholarship, along with insights from rational choice and sociological institutionalism. Under this theory, central and local party actors have different—at times, conflicting—goals over candidate selection. These goals sometimes lead them to prefer different nomination candidates. Both central and local party actors have access to gatekeeping practices through which they can influence the outcomes of candidate selection, but central party actors are more able to block particular candidates from running and keep nominations from becoming contested. When central and local party actors disagree over which prospective candidate should win the nomination, the outcome is generally a contested nomination and/or gatekeeping by central party actors to prevent a contested nomination. While gatekeeping by central party actors is not always effective in determining the outcome, it substantially reduces the probability of a contested nomination.

I build this theory with material from a 20-month multi-method field study of candidate nominations for the 2018 New Brunswick provincial election. I conducted 93 interviews with 70 party insiders, nomination candidates, potential candidates, and other individuals with knowledge of candidate selection in New Brunswick's political parties, and I conducted participant-observation of 25 nominating conventions. I reviewed documentary evidence on candidate selection, including newspaper coverage, party rules, court records and social media posts. I created an original dataset on nominations in the Liberal and Progressive-Conservative (PC) Parties that combines electoral results and political finance records on nomination races with qualitative evidence on the use of gatekeeping from interviews, participant-observation and documentary evidence.

This study makes three main contributions. First, it brings together past findings on candidate selection into a theoretical account of how party insiders exert influence over candidate selection. Second, it demonstrates that gatekeeping plays a major role in explaining why nominations go uncontested, even in competitive and safe seats. Third, it generates several testable claims about gatekeeping for future studies of candidate selection in other places, time periods and levels of government in Canada.

The Concept of Gatekeeping

By gatekeeping, I mean party actors’ use of institutional rules or practices to influence the outcomes of candidate selection, despite formal rules and party norms that allow party members or supporters to vote on the choice of the local candidate. Gatekeeping occurs because party actors have preferences over potential candidates and institutional rules and practices through which they can influence candidate selection. The recruitment process often shapes party actors’ preferences and gatekeeping decisions, but recruitment is analytically separate from gatekeeping. Gatekeeping can serve either to help preferred candidates win nominations or to prevent non-preferred candidates—or even unacceptable candidates—from winning nominations.

This concept of gatekeeping is distinct from two related concepts. First, it is distinct from what American parties scholars call “party control” over nominations (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Karol, Noel and Zaller2009; Hassell, Reference Hassell2017; Masket, Reference Masket2009). Unlike party control, gatekeeping does not presume that the party organization generally unifies behind a single preferred candidate. Instead, different actors within a party organization—such as central and local party actors in Canada—may engage in gatekeeping on behalf of different preferred candidates. Second, gatekeeping is distinct from what gender scholars call “informal influences” in candidate selection (Cheng and Tavits, Reference Cheng and Tavits2011). Gatekeeping differs from informal influences because it includes both formal (written) and informal (unwritten) institutional activities. For example, when vetting committees keep prospective nomination candidates from running, they are using a formal power under party rules. By contrast, when party leaders or their staff influence the date of a nominating convention, they are using an informal practice to help their preferred candidate win.Footnote 1

I identify two types of gatekeeping—competitive and anti-competitive gatekeeping. Party actors engage in competitive gatekeeping when they provide resources to preferred candidates’ nomination campaigns. For example, various party actors can provide advice to their preferred candidates or refer them to organizers or volunteers who can help them with their nomination campaigns. Similarly, as I observed during my fieldwork, former candidates and elected members can provide endorsements to their preferred candidates.

By contrast, party actors engage in anti-competitive gatekeeping when they take actions to make it more difficult for non-preferred candidates to run, let alone win. For example, in Canadian parties, any party actor may attempt to discourage non-preferred candidates from running by talking to them. Party leaders can refuse to sign non-preferred candidates’ nomination papers (Courtney, Reference Courtney1978; Cross, Reference Cross, Pammett and Dornan2006; Erickson and Carty, Reference Erickson and Carty1991). Vetting committees can prevent non-preferred candidates from running by rejecting their candidate applications (Marland and DeCillia, Reference Marland and DeCillia2020; Pruysers and Cross, Reference Pruysers and Cross2016). Central party organizations can manipulate the dates of nominating conventions to make it more difficult for non-preferred candidates to run or win (Pruysers and Cross, Reference Pruysers and Cross2016; Thomas and Morden, Reference Thomas and Morden2019). For example, they may call early conventions (nominating conventions early within the nominations cycle, usually more than a year before the next election) or snap conventions (nominating conventions on short notice). Early conventions make it more difficult for non-preferred candidates by calling a nominating convention before those candidates even express an interest in running. Usually, they take place when central party organizations have recruited a preferred candidate, and no other candidate has expressed an interest in running. Snap conventions make it more difficult for non-preferred candidates to win because those candidates have limited time to convince their supporters to sign up as party members or turn out at the nominating convention. Typically, central party actors will call a snap convention when they believe a non-preferred candidate could become more likely to win than their preferred candidate if the nomination campaign ran over a longer period of time.

Given the norms of intra-party democracy, competitive gatekeeping is generally more acceptable than anti-competitive gatekeeping. Competitive gatekeeping practices are socially understood as routine occurrences, and they do not usually prevent anyone from running for the nomination. Anti-competitive gatekeeping practices are hard to reconcile with the idea that party members and supporters should have the right to select local candidates, because they deny party members and supporters the ability to choose certain candidates.

A Theory of Gatekeeping

This section outlines an institutionalist theory of gatekeeping by central and local party actors. The theory draws on insights from rational choice and sociological institutionalism (Hall and Taylor, Reference Hall and Taylor1996) and brings together many of the existing findings on candidate selection from Canada and elsewhere. It applies to parties that (1) run in district elections (rather than one nationwide proportional representation system), (2) regularly win seats and (3) have both central and local organizations. Throughout this section, I highlight observable implications of the theory. Below, I use qualitative and quantitative evidence to show that these observable implications hold in practice.

In any political party, the structure of the party organization shapes which actors are relevant gatekeepers. In Canada, gatekeepers can include not only riding association executives but also party leaders and their staff, party executives and employees, elected officials, other nominated candidates, and retired politicians. For the sake of parsimony, I simplify the actors into two networks—central (party leaders’ offices, formal party organizations, and prominent non-local party members) and local (riding associations and prominent local party members). I call them networks to make the link explicit between this study and others that conceptualize political parties as networks (Koger et al., Reference Koger, Masket and Noel2009; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1990).

Party institutions can empower different actors to engage in gatekeeping. Since 1970, central party actors—including party leaders and vetting committees—have gained access to gatekeeping practices as political parties have become regulated in law and changed their own rules. In 1970, the Canada Elections Act added party labels to the ballot for the first time. To ensure that only official party candidates can claim the party label on the ballot, the law stipulates that party leaders must sign candidates’ nomination papers. Party leaders and their staff realized that they could use this power as a “leader's veto.” They could block unacceptable candidates by refusing to sign their nomination papers, even if the candidates had won the nomination through a nominating convention (Courtney, Reference Courtney1978; Erickson and Carty, Reference Erickson and Carty1991). Since the 1990s, Canadian parties have adopted candidate-vetting processes that require candidates to submit candidate applications and undergo background checks (Marland and DeCillia, Reference Marland and DeCillia2020). Over time, this vetting process has come to include in-depth social media checks by party researchers. Vetting committees can reject candidate applications and keep “undesirable” candidates off the ballot at nominating conventions. Finally, in the early 1990s, the Liberal Party of Canada gave the party leader the explicit power to appoint candidates, bypassing the usual nominating process (Baisley, Reference Baisley2020; Koene, Reference Koene2008; Koop and Bittner, Reference Koop and Bittner2011). Provincial Liberal parties have since adopted similar appointment powers. These changes in party institutions have given central party actors new gatekeeping practices through which they can prevent prospective candidates from running in the first place or ensure that their preferred candidates win nominations uncontested.

At the same time, party institutions and norms can constrain party actors’ ability to gatekeep. In Canadian parties, there is a “norm of non-interference” in candidate nominations in which local associations are supposed to choose their own candidates without interference from the centre (Carty, Reference Carty and Kenneth1991, Reference Carty and Kenneth2002, Reference Carty2004). The norm of non-interference rests on the commonplace understanding that candidate nominations are supposed to be internally democratic. As with all social norms, the existence of the norm does not mean that everyone always follows the norm.Footnote 2 Indeed, the norm of non-interference exist even though “in no instances are the local members able to select a candidate completely free from the interference of central party dictates, while in many cases the central party is able to select a candidate without local party members being able to influence the choice” (Cross, Reference Cross, Pammett and Dornan2006: 176). Although anti-competitive gatekeeping practices, such as the leader's veto, rejecting candidates after vetting, and manipulating nominating conventions, are accepted practices among party insiders, they contravene the social understanding that local party members or supporters are supposed to be the ones who pick the local candidates, not the centre. The use of anti-competitive gatekeeping practices by central party actors can provoke a backlash from local party actors that can attract unwanted media attention for central party actors. This risk of backlash is particularly acute for party leaders, who face the most media scrutiny.

Observable Implication 1: Party actors acknowledge the existence of a norm of non-interference in candidate selection and the constraints the norm of non-interference place on their use of gatekeeping.

Various party actors typically have multiple goals that shape their preferences over potential candidates. In addition, they frequently have first- or secondhand knowledge of potential candidates, which helps them determine which potential candidates will help them meet their goals. Importantly, different actors within the same party can have conflicting goals over candidate selection (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1990).

In Canada, central and local party networks can have different goals that shape their preferences in candidate selection. Traditionally, policy considerations have not been major factors in local nomination races in Canada, particularly in the Liberal and Conservative Parties (Carty, Reference Carty and Kenneth1991; Sayers, Reference Sayers1999). Instead, the central network tends to prioritize winning the most—or a majority—of seats, ensuring that prospective cabinet ministers win nominations in ridings they are likely to win, obtaining positive news coverage, and avoiding negative news coverage, especially about the leader. For these reasons, central networks are more likely to prioritize the selection of women and racialized minority groups, as Canadian and comparative work suggests (Bjårnegard and Zetterberg, Reference Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2016; Cross et al., Reference Cross, Kenig, Pruysers and Rahat2016; Hazan and Rahat, Reference Hazan and Rahat2010; Norris, Reference Norris, LeDuc, Niemi and Norris1996). By contrast, local networks tend to prioritize winning that seat and picking “good constituency representatives” who will attend events in the riding, respond to constituency casework and otherwise advocate for people in the riding. For example, in the 2018 Liberal nomination race in Kent North, the preferred candidate of the central network was Dan Murphy, former executive director of the New Brunswick Liberal Association, while the preferred candidate of the riding association was Emery Comeau, former executive assistant to outgoing incumbent Bertrand LeBlanc. The central network viewed Kent North as an opportunity to run a potential cabinet minister in a safe seat (Interviews 18, 29). However, Emery Comeau had experience handling constituency casework and working with a members riding association before the 2013 redistribution, which gave him strong local connections (Interview 18).

Although party actors may have many goals that shape their approach to candidate selection, electoral competition plays a major role in shaping the dynamics of candidate selection (Carty, Reference Carty and Kenneth1991; Carty and Eagles, Reference Carty and Eagles2005; Sayers, Reference Sayers1999). As party actors’ impressions of the party's chances of winning the seat in the general election become more optimistic, that party's nomination becomes more desirable, and contested nominations become more likely. In addition, rational party actors value each candidate's ability to generate a “personal vote” in the riding the most when the choice of candidate can make a difference at the margin in whether the party wins an additional seat—that is, in the most competitive ridings in general elections. They do not value candidates’ personal votes at all when there is no reason to expect that the candidate will make any difference in whether the party wins an additional seat, as in “hopeless” or “safe” ridings. Finally, although the central network is, in principle, always able to engage in gatekeeping over nominations, local networks vary considerably in terms of their organizational strength. Local party organizations tend to be stronger where parties perform better in general elections (Carty, Reference Carty and Kenneth1991; Carty and Eagles, Reference Carty and Eagles2005; Sayers, Reference Sayers1999). Stronger local organizations can help or resist the centre.

Observable Implication 2: Contested nominations are more likely to occur as ridings become more competitive.

Incumbents play a major role in shaping the preferences of party actors. Due to their experience and social ties, they are typically capable of constructing local campaign organizations. These organizations play an important part in general election outcomes (Carty and Eagles, Reference Carty and Eagles2005; Cross, Reference Cross2016). However, they also allow incumbents to fend off nomination challenges. When a candidate wins a nomination, that candidate may “stack” the executive of the local party organization with their supporters from the nomination campaign (Koop, Reference Koop2010). These dedicated supporters will tend to support an incumbent. On top of these relationships, local and central networks typically have electoral incentives to value incumbents. It is hard to know which candidates will perform well in elections, but incumbents are proven winners. Unless incumbents are inattentive to their ridings or face major scandals or otherwise give party actors reasons to think they are a liability, central and local actors tend to agree on renominating them. In fact, in recent decades, Liberal and Conservative party leaders have guaranteed the renomination of all incumbents—or incumbents who meet pre-set campaign targets (Cross, Reference Cross, Pammett and Dornan2006; Thomas and Morden, Reference Thomas and Morden2019).

Observable Implication 3: Contested nominations are more likely to occur in ridings without incumbents than ridings with incumbents.

In non-incumbent ridings, competitive nomination races tend to emerge when different actors within party organizations prefer different candidates. In Canadian parties, central and local networks often engage in their own recruitment processes, and relatively few individuals (25 per cent) become candidates without contact from either network (Cross and Young, Reference Cross, Young, Bittner and Koop2013). When central and local actors recruit candidates or identify promising candidates who step forward on their own, they develop preferences over potential candidates. Both central and local actors usually favour candidates they themselves recruited. When the central and local networks agree over a preferred candidate, they are often able to orchestrate that individual's nomination, especially when the other interested candidates are inexperienced amateurs. When they disagree, however, they either engage in competing gatekeeping efforts to influence the process behind the scenes or allow a competitive nomination process to resolve the conflict over who will become the candidate.

Observable Implication 4: If central and local party networks agree on a single preferred candidate and no insurgent candidates seek the nomination, the nomination is likely to go uncontested.

Observable Implication 5: If competing party networks disagree over their preferred candidates, then either (1) the central party network will engage in anti-competitive gatekeeping to prevent the nomination from becoming contested or (2) competing preferred candidates run against each other in a contested nomination. This expectation means that the combination of an uncontested nomination and no anti-competitive gatekeeping is unexpected when competing party networks disagree over their preferred candidates.

It is possible for non-preferred (or outsider) candidates to run for and win nominations even when central and local party actors engage in gatekeeping. Some outsider candidates are amateurs who have little support within the party and, consequently, often lose. Others are insurgent candidates who have backing from outside organizations that can help them win nominations despite a lack of insider support. Past work identifies two major types of insurgent candidates. The first consists of candidates who mobilize support from within immigrant communities of a shared national origin (Cross, Reference Cross2004, Reference Cross, Pammett and Dornan2006; Scarrow, Reference Scarrow1964). Ethnic networks are a powerful means of mobilizing individuals to sign up as members and turn out to vote. The second consists of candidates who have the backing of movement organizations, particularly social conservative organizations (Baisley, Reference Baisley2020; Cross, Reference Cross2004, Reference Cross, Pammett and Dornan2006). These candidates may have support from organizers that understand how the nomination process works and can help them sign up members using the organization's list of supporters. Insurgent candidates may put pressure on central and local party actors to work together to help another candidate win. For example, both central and local party actors may prefer not to nominate candidates who have stronger ties to outside organizations than to the party organization itself. If so, then the threat of an insurgent candidate may push them to work together. Even if central and local party actors want to keep these insurgent candidates from winning the nomination, they may not be successful in doing so, especially if they allow the nomination to become contested. Although insurgent candidates undoubtedly exist in federal politics, I put insurgent candidates aside because I did not observe such candidates during my fieldwork in New Brunswick.

Competitive and anti-competitive gatekeeping practices have different implications for the probability of contested nominations. Competitive gatekeeping practices usually take place when party actors expect a contested nomination to occur. By contrast, anti-competitive gatekeeping practices usually take place when party actors would prefer to avoid a contested nomination in the first place. Anti-competitive gatekeeping practices are effective in reducing the probability of a contested nomination. Some anti-competitive gatekeeping practices, such as the leader's refusal to sign a candidate's nomination papers or rejecting a candidate's application to run after the vetting process, can be completely effective in ensuring that a nomination goes uncontested. If party leaders refuse to sign the nomination papers of anyone who could compete with their preferred candidate, or vetting committees only approve one candidate application, they can ensure the nomination goes uncontested. In practice, however, party leaders and vetting committees may only use these anti-competitive gatekeeping practices to block particularly undesirable candidates but not other non-preferred candidates. Other anti-competitive gatekeeping practices, such as calling early or snap conventions, may not always work. When non-preferred candidates are familiar with early or snap conventions, they are better able to anticipate their use and mount nomination campaigns anyway.

Observable Implication 6: When central party actors use anti-competitive gatekeeping practices in a nomination race, contested nominations become less likely to occur.

Case Selection

This theory of gatekeeping generates several observable implications that require not only quantitative data across ridings but also qualitative insight into perceptions of the norm of non-interference, the preferred candidates of different party actors, and their gatekeeping practices. Unfortunately, Canada is too geographically large to gain such qualitative information across all parties and ridings. For this reason, I conducted a study of party nominations during and after the 2018 New Brunswick election. New Brunswick's small size makes it feasible to visit every riding and observe individual nomination races across parties and ridings.

New Brunswick offers theoretical advantages over other provinces. Past research on candidate selection overwhelmingly focuses on federal politics. New Brunswick resembles federal politics in some important respects that do not hold for other provinces. Most notably, New Brunswick is the only province whose linguistic and religious demographics have historically resembled Canada as a whole. New Brunswick's party system shares many of the same linguistic and religious divisions that have historically shaped federal party politics (Carty and Eagles, Reference Carty and Eagles2003; Cross and Stewart, Reference Cross and Stewart2002; Cross and Young, Reference Cross, Young and Cross2007). In addition, New Brunswick's provincial political parties share many of the same candidate selection institutions as in federal politics, apart from lower or even no membership dues (Cross and Young, Reference Cross, Young and Cross2007). Finally, New Brunswick's federal and provincial parties are highly vertically integrated in terms of personnel (Koop, Reference Koop2011).Footnote 3 This overlapping membership makes it likely that federal and provincial party actors will learn from one another's gatekeeping practices, as they do with electoral strategies (Esselment, Reference Esselment2010).

New Brunswick provincial politics has a few main differences from federal politics that shape candidate selection. First, New Brunswick's small scale, which is critical to making this project feasible, may affect the research findings. In New Brunswick, political, economic and social elites fall within relatively small networks. These connections may make it easier for central party actors to run centralized recruitment efforts—and identify preferred candidates—without relying on local party actors. By contrast, in federal politics, it may be more difficult for central party organizations to identify promising local candidates without help from local or provincial actors. Second, New Brunswick has not been a major destination for immigrants since the nineteenth century. New Brunswick's low levels of immigration may help explain why New Brunswick's parties do not have to contend with insurgent candidates who rely on support from within immigrant communities. Third, outside organizations, such as social conservative organizations, have largely not attempted to run their own candidates in provincial nominations in New Brunswick. As a result, in New Brunswick, central and local party networks do not face the same threat of insurgent candidates that federal parties do, which may lead them to disagree over competing preferred candidates rather than unite to stop an insurgent candidate. Although these aspects of the New Brunswick case undoubtedly limit the ability of this study to generalize to federal politics, some of the claims of the theory already have support in federal politics, including the importance of riding competitiveness and incumbency (Carty, Reference Carty and Kenneth1991; Carty and Eagles, Reference Carty and Eagles2005; Sayers, Reference Sayers1999) and the existence of central and local disagreement over preferred candidates (Erickson and Carty, Reference Erickson and Carty1991).

Data and Methodology

I spent over 20 months conducting fieldwork in New Brunswick, including 16 months before the 2018 New Brunswick election. During that time, I conducted 93 interviews with 70 individuals familiar with different aspects of candidate selection in New Brunswick's political parties. Interviewees included current and former nomination candidates, potential nomination candidates, party leaders, their staff, executive directors, riding association presidents, staffers involved in vetting candidates, and other individuals with knowledge of candidate selection in New Brunswick's parties. Since the backroom politics of nominations is often sensitive, I made the decision in advance to conduct the interviews as confidential but quotable without attribution. I allowed respondents to go completely off the record, as needed, to gain additional insight into the nominations process. I offered interviewees a choice between English or French interviews. I conducted all but two interviews in English. For additional details on the interview methodology, please see the supplementary materials. These interviews help substantiate the norm of non-interference, identify cases of intra-party disagreement over preferred candidates, and identify the use of gatekeeping practices in particular nomination races.

In addition to the interviews, I conducted participant-observation of 25 nominating conventions. These nominating conventions included all but two contested nominations across the five parties that had a chance of winning at least one seat in the Legislative Assembly—the Progressive-Conservative (PC) Party, the Liberal Party, the New Democratic Party (NDP), the Green Party and the People's Alliance of New Brunswick (PANB). The exceptions were the contested PANB nomination in Southwest Miramichi–Bay du Vin, which took place at the same time as a contested PC nomination in Fundy–The Isles–Saint John West, and the contested PC nomination in Albert, which took place at the same time as a contested Liberal nomination in Kent North. For full details on the ridings observed, please consult the supplementary materials. Informal chats with party insiders at nominating conventions shed light on the norm of non-interference, their preferred candidates, and their use of gatekeeping practices. Attending nominating conventions also helped me recruit interview participants, since many interviewees were more likely to respond to a recruitment letter or email if they had already met me.

I also draw on documentary evidence. During the field research, I read newspaper coverage of nomination races, nomination candidates’ Facebook and Twitter pages, and all the documents and information on nomination contests available on political parties’ websites. These documents have valuable information both on the formal rules and on nomination races that became major news stories. I also gathered court documents from a legal dispute between Chris Duffie and the New Brunswick PCs over the Carleton–York PC nomination.

In addition, I constructed an original nominations dataset for the 2018 provincial election. I built the dataset by starting with riding-level electoral results from the 2014 and 2018 elections and political finance records on nomination races for the 2018 election. In 2015, New Brunswick became the first province to regulate nomination races under political finance law. Under the new political finance regulations, each party must file a Certificate of Nominating Convention that lists the date of the nominating convention, the location of the convention, the contestants for the nomination and the name of the winner. Nomination candidates must also file disclosure reports that either declare that the funds raised for their nomination campaign fall under $2,000 or detail their donations and expenses if they raise $2,000 or more. I use the publicly available data to code contested nominations (0 = one nomination candidate, 1 = more than one nomination candidate).Footnote 4

I supplement the publicly available data with several variables from my fieldwork. I code disagreement between central and local party actors over their preferred candidates based on the interviews, participant-observation and documentary evidence (0 = no disagreement, 1 = disagreement). I code the use of anti-competitive gatekeeping practices by the central party organization as a binary variable (0 = no gatekeeping observed, 1 = gatekeeping observed). These practices include discouragement, snap conventions, early conventions and rejecting candidates after the vetting process.Footnote 5 They do not include competitive gatekeeping practices because they do not generally influence the outcome by preventing a contested nomination from taking place. This variable is binary for both theoretical and practical reasons. Theoretically, the claims about gatekeeping and contested nominations are about the use—or not—of anti-competitive gatekeeping practices. For this reason, I do not include competitive gatekeeping practices in the variable. The theory also does not generate clear expectations about the number of anti-competitive gatekeeping practices used. Indeed, the use of multiple anti-competitive gatekeeping practices in the same nomination race may be a sign that an attempt at anti-competitive gatekeeping failed, and central party actors turned to an alternative solution later. Empirically, there is little variation in the number of gatekeeping practices used given that one gatekeeping practice is used. In addition, I code the perceived electoral competitiveness of each riding (0 = hopeless, 1 = competitive, 2 = safe) based on interviews. In the online supplementary materials, I replicate the analyses that use this variable using the party's vote share in the 2014 election as a measure of the actual competitiveness of each riding.

I do not claim to have identified every case of disagreement and gatekeeping, since party actors are generally reluctant to discuss the backroom politics of nominations. While I identify many cases of disagreement and gatekeeping from questions about specific nomination races, party insiders may not have mentioned every instance of disagreement or gatekeeping. As a result, these known cases serve as lower bounds for the true extent of disagreement and gatekeeping. This possibility of understating the true extent of disagreement and gatekeeping is particularly salient for some PC insiders, who were more reluctant to discuss internal party business.

I use the qualitative and quantitative material to present evidence for each of the observable implications, in the same order as the observable implications appear above.

The Norm of Non-Interference: Interview Evidence

I present evidence for the “norm of non-interference” using evidence from my interviews. Many party actors, particularly in the central party network, face a “norm of non-interference” that constrains their ability to engage in gatekeeping in candidate selection (Observable Implication 1). Across many interviews, party insiders emphasized that the norm was for the party leader's office, the party's legislative office, party headquarters, the party's legislative caucus, and the president of the local riding association to remain neutral in nomination races. For many party insiders, this neutrality was an important part of keeping nominations democratic. Party insiders acknowledged the importance of this norm even though they overwhelmingly acknowledged that these actors usually were not neutral in practice.

Both party actors and news media enforce this norm. When riding associations perceive “interference” from the centre, they can resist it by bolting from the party (Interviews 63, 69). For example, the Liberal riding association executive in Moncton Centre resigned after Premier Brian Gallant expelled local member and Speaker Chris Collins from caucus over allegations of sexual misconduct (Poitras, Reference Poitras2018). Mass resignations deprive the central party organization of a pre-existing local organization for the general election. Journalists also play a major role in enforcing this norm. A Liberal from the Premier's Office said, “We [political staffers] are all terrified of the story [of manipulation] in the newspaper” (Interview 58). PC insiders likewise agreed that interference risked a backlash (Interviews 10, 19).

This norm of non-interference, combined with the risk of public criticism for violating it, explains why central party actors do not simply use anti-competitive gatekeeping practices in every nomination race. Party leaders generally do not use their most powerful gatekeeping powers, such as appointments or the leader's veto. These gatekeeping activities not only publicly violate the norm of non-interference but also risk antagonizing a potential candidate who could go to the news media with a story that could damage the party leader. Rejecting candidates after the vetting process does not pose the same risks because the vetting process insulates the leader from criticism by giving the authority to block undesirable candidates from running to a committee (Interview 1, Interview 2). For this reason, rejecting candidates’ applications has become more common than appointments or the leader's veto.

Instead, both central and local party networks rely on private means to influence the nomination race (Cross, Reference Cross, Pammett and Dornan2006; Koop, Reference Koop2010; Pruysers and Cross, Reference Pruysers and Cross2016; Sayers, Reference Sayers1999). A senior Liberal insider described the usual approach: “You try to do it without being caught. You quietly, aggressively recruit people you want. You give them advice. Maybe you call a few good organizers. You pick a date at a time that suits your preferred candidate. If you are in a larger, rural riding, you pick a location that suits your preferred candidate” (Interview 58). The same insider indicated that these activities “all have plausible deniability. . . . You do things you can deny. If a leader calls someone to tell them not to run, they can't say they were drunk and called the wrong person” (Interview 58). Other former Liberal and PC insiders described the process similarly (Interview 8, 10). Private gatekeeping activities are often not as powerful as public activities, but they are often more desirable. They help party actors subject to the norm of non-interference avoid the impression that they are exerting influence over candidate selection, even when they are.

Explaining Contested Nominations: Quantitative Nominations Data

I explain why some nominations became contested using the quantitative data on Liberal and PC nominations for the 2018 New Brunswick Election. First, I show that contested nominations are more likely to occur in ridings where the party is more competitive (Observable Implication 2) and in ridings where the party does not have an incumbent (Observable Implication 3). Second, I demonstrate that nominations go uncontested when party actors do not disagree over their preferred candidates (Observable Implication 4). Third, I show that disagreement between different party actors is associated with either the use of gatekeeping practices by central party actors or the emergence of contested nominations (Observable Implication 5). Finally, I present quantitative evidence that gatekeeping by central party actors reduces the likelihood of contested nominations (Observable Implication 6).

Figure 1 displays the frequency of disagreement among party actors over preferred candidates and contested nominations across four types of districts.Footnote 6 Based on the theoretical framework outlined above, I group ridings in which an incumbent is seeking re-election, and then I subdivide non-incumbent ridings into three categories of perceived electoral competitiveness (safe, competitive and hopeless). These categories of electoral competitiveness draw on the general perceptions of party insiders and New Brunswick politics experts from my field research. Party insiders tend to view the competitiveness of ridings in subjective categories, rather than as continuous variables (Bodet, Reference Bodet2013). These subjective perceptions incorporate information about riding histories, local disgruntlement with incumbents, and other information that objective measures of competitiveness may miss. Finally, subjective perceptions of competitiveness better align with the theory. In the online supplementary materials, I include additional checks using the party's margin of victory or loss in the 2014 election.

Figure 1 Internal Disagreement and Contested Nominations for the 2018 New Brunswick Election, by Party and Riding Context

Note: N = 49 for both the Liberals and the PCs in each panel.

As Figure 1 shows, both disagreement over preferred candidates and contested nominations are rare in incumbent seats. In non-incumbent seats, the greater the party's chances of winning the riding, the more likely there is disagreement within the party over preferred candidates, and the more likely the nomination is contested. This is true for both the Liberals and the PCs.

Next, I examine theoretical prediction that disagreement over preferred candidates leads to contested nominations (Observable Implication 5). Figure 2 shows a bivariate graph of the relationship between pre-convention intra-party disagreement over preferred candidates and a contested nomination. As it makes clear, intra-party disagreement is a very strong predictor of contested nominations. The cross-tabulations for these graphs are highly statistically significant using a chi-square test (for the Liberals, χ 2 = 22.47 and p < .001; for the PCs, χ 2 =19.25 and p < .001). When there is no observed intra-party disagreement on a preferred candidate, the nomination usually goes uncontested (Observable Implication 4). However, intra-party disagreement does not always lead to a contested nomination. This bivariate graph illustrates that contested nominations are generally the product of disagreement between different actors within the party organization in recruitment, rather than outside candidates seeking the nomination. Figure 2 may understate the strength of intra-party disagreement because I code cases of disagreement only when I observed it in interviews or in participant-observation, even if I suspected that party insiders were not being forthcoming about disagreement.

Figure 2 Percentage of Contested Nominations, by Intra-party Disagreement and Party

Note: N = 49 for both the Liberals and the PCs.

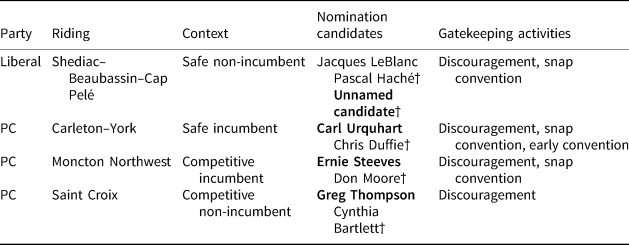

I turn to the prediction that disagreement will result either in gatekeeping or a contested nomination (Observable Implication 5). Since this claim only applies in cases in which competing party networks disagree over their choice of candidate, I restrict the analysis to cases in which I observed disagreement in my field research. Table 1 displays the use of gatekeeping activities in nomination races when central and local party actors disagreed over their preferred candidates. Given the small number of cases, it is important to interpret Table 1 with caution. That said, Table 1 shows that when different networks in the Liberal and PC Parties disagreed over their choice of a preferred candidate, the outcome was either gatekeeping or a contested nomination. The cell for no gatekeeping and an uncontested nomination is empty, as predicted.

Table 1 The Use of Gatekeeping Activities and Contested Nominations, Cases of Disagreement over Preferred Candidates Only, by Party

Finally, I examine the expectation that gatekeeping by central party actors reduces the probability of a contested nomination (Observable Implication 6). Table 1 also illustrates the effectiveness of gatekeeping in cases of intra-party disagreement over preferred candidates. In bivariate analyses, it is important to restrict the analysis to cases of intra-party disagreement because party actors tend not to engage in gatekeeping when there are multiple prospective candidates unless there is some reason why they perceive an interest in influencing the nomination. Since gatekeeping and contested nominations both tend to occur in cases of disagreement, similar bivariate analyses on the full dataset suggest that gatekeeping increases contested nominations. This result is a bias of not controlling for intra-party disagreement.

Although the number of cases is small, Table 1 shows that contested nominations are less likely when central party networks engage in gatekeeping. This pattern exists in both parties. However, gatekeeping does not always work. In both parties, contested nominations still occurred despite the use of gatekeeping. I run Fisher's exact test to estimate the probability that these results are not due to chance. Fisher's exact test is more suitable than a chi-square test for small cell sizes. When I pool both major parties, that cross-tabulation is statistically significant (p < 0.01). For the Liberals, this cross-tabulation falls short of statistical significance (p = 0.2). However, for the PCs, it is statistically significant (p < 0.05) despite the small cell counts.

As an additional test that anti-competitive gatekeeping reduces the probability of a contested nomination, I model contested nominations as a function of perceived district competitiveness, incumbency, observed intra-party disagreement and observed anti-competitive gatekeeping.Footnote 7 I run these models on both Liberals and PC nominations together, given the small number of ridings in New Brunswick. I estimate these models using penalized maximum likelihood (Firth, Reference Firth1993), which is more appropriate in small samples than conventional maximum likelihood (Rainey and McCaskey, Reference Rainey and McCaskey2021). Table 2 displays the results of this model. In the online supplementary materials, I replicate these results using the party's win margin in 2014 as an objective measure of district competitiveness. The results are substantively similar to the ones presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Logistic Regression of Contested Nomination on Perceived District Competitiveness, Incumbency, Observed Intra-party Disagreement and Observed Anti-competitive Gatekeeping, Estimated with Penalized Maximum Likelihood

Note: The reference category for district competitiveness is hopeless districts. The brackets include 95% confidence intervals. * p < .05.

As Table 2 shows, contested nominations are more likely in competitive and safe ridings (Observable Implication 2). They are less likely in incumbent ridings (Observable Implication 3). Although the coefficients for these variables have the expected signs, neither perceived electoral competitiveness nor incumbency is statistically significant given the small number of observations. (In the online supplementary materials, I present additional models that indicate that the inclusion of observed intra-party disagreement and anti-competitive gatekeeping helps explain the non-significance of these variables.) Observed intra-party disagreement predicts contested nominations (Observable Implication 5). Finally, observed anti-competitive gatekeeping is associated with a lower probability of a contested nomination (Observable Implication 6). Both observed intra-party disagreement and anti-competitive gatekeeping are statistically significant. This model generally confirms the expectations of the theory outlined above.

Figure 3 helps illustrate the substantive implications of the model in Table 2. It displays the predicted probability of a contested nomination based on observed disagreement and anti-competitive gatekeeping from the model in Table 2. Figure 3 indicates that the predicted probability of a contested nomination is around 0.06 when there is no observed disagreement as opposed to 0.76 when there is observed disagreement—a difference of 0.70. In the same model, the predicted probability of a contested nomination is 0.20 when gatekeeping is not observed, as opposed to 0.06 when gatekeeping is observed—a difference of −0.16. These differences in predicted probabilities are statistically significant (p = 0.05).

Figure 3 Predicted Probability of Contested Nominations, by Observed Intra-party Disagreement and Anti-competitive Gatekeeping

Note: The model also includes controls for perceived district competitiveness and incumbency. The results for these variables are available in Table 2. N = 98.

Anti-Competitive in Near-Contested Nominations: Four Case Studies

I examine why central party actors engaged in anti-competitive gatekeeping and how their activities prevented contested nominations (as Observable Implication 6 suggests) through case studies of near-contested nominations. By near-contested nominations, I mean cases in which two or more nomination candidates expressed an interest in running at the same time but the nomination went uncontested.

I focus on near-contested nominations for three reasons. First, near-contested nominations are the most likely cases to find anti-competitive gatekeeping activities. When only one person wants the nomination, party actors have no reason to engage in gatekeeping, as it will not affect the outcome. Likewise, contested nominations may occur because party actors simply did not engage in anti-competitive gatekeeping in the first place. Second, near-contested nominations are the most likely cases to illustrate that gatekeeping activities can meaningfully prevent a prospective candidate from running the nomination. Third, these near-contested nominations help substantiate claims about why party actors engage in gatekeeping through a close study of mechanisms.

I observed four public cases of near-contested nominations. I limit the analysis to public cases to avoid presenting case studies that could potentially identify interview participants. I display these cases in Table 3. For each nomination, I present the party, the riding, the riding context (incumbent seats, safe non-incumbent seats, competitive non-incumbent seats and hopeless non-incumbent seats), the names of the prospective nomination candidates (if they are public information) and the gatekeeping activities observed. I indicate the central party organization's preferred candidates in bold and candidates blocked or deterred from running using a dagger (†).

Table 3 Gatekeeping Activities in Near-Contested Nominations for the 2018 New Brunswick Election

Note: The central party organization's preferred candidates are shown in bold; candidates blocked or deterred from running are marked with a †.

I observed one near-contested Liberal nomination. In Shediac–Beaubassin–Cap Pelé, one of the safest Liberal seats in New Brunswick, the Premier's Office attempted to recruit a woman to run (Interviews 29, 58). However, Shediac mayor Jacques LeBlanc began campaigning for the nomination as soon as it became clear that long-time Liberal incumbent Victor Boudreau was retiring (Interview 23). Ultimately, LeBlanc deterred the central network's preferred candidate from running by obtaining substantial support from local party actors (Interview 29, 58). The central party network approved a nomination call for January 27. This snap convention was enough to deter another interested candidate, Pascal Haché, from running.Footnote 8

For the PCs, I found three near-contested nominations. The most well-documented case is the PC nomination in Carleton–York. There, Chris Duffie sought to challenge incumbent PC Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) Carl Urquhart. Duffie previously ran for a PC nomination for the 2010 election. He expressed an interest in running as the PC candidate in Carleton–York after Urquhart retired. Urquhart took him as a protégé and gave him “exposure” by involving him in constituency work (Interviews 17, 39). Until late in 2016, the understanding was that Urquhart was not going to run in the next election (Interviews 17, 19, 22, 39). Urquhart changed his mind, and Duffie had a falling out with Urquhart over that decision. In 2017, Duffie spent months campaigning for the nomination (Interviews 17, 19, 22). One PC insider suggested that Duffie would have been “the favourite” if Urquhart had not run again (Interview 38). However, when Duffie decided to challenge Urquhart, central and local PC insiders took several actions to prevent him from appearing on the ballot at the nominating convention.

PC central party insiders made it very clear in interviews that they did not want Duffie to run, especially against a popular incumbent (Interviews 19, 22). In April 2017, Fredericton party actors tried to dissuade Duffie from running against a sitting MLA (Interviews 17, 19).Footnote 9 According to an interviewee in the room at the time, one of them suggested that Duffie could run in another riding, such as Fredericton South (Interview 17). Fredericton South was a much less desirable seat, since Green Party leader David Coon had won it in a four-way race in 2014. Duffie claimed that he had a meeting with PC leader Blaine Higgs and his chief of staff, Dominic Cardy, in which Cardy offered Duffie a job not to run, though Cardy denied this.Footnote 10

On May 4, 2017, PC Party of New Brunswick president and acting executive director Don Moore sent out an email to its members advising them of upcoming nomination contests—the first email communication of the 2017–2018 nominations cycle. It did not mention that May 5 was the deadline for submitting paperwork to the party to run in the riding of Carleton–York. Instead, on May 4, the party organization notified potential nomination contestants and the party membership of the convention through an ad on page C3 of the Life section of the Fredericton Daily Gleaner.Footnote 11 The ad called the convention for May 19, 2017—the Friday of Victoria Day long weekend. The party set the location as Canterbury High School—a relatively small venue in a rural community in the southwestern part of the riding where PC leader Blaine Higgs had attended.

Duffie did not find out about the nomination call until he ran into someone at Costco on May 6. He sent an email to PC Party president and acting executive director Don Moore that day declaring his intent to run.Footnote 12 The following Monday, May 8, he went to the PC Party headquarters to try to submit his paperwork to contest the nomination, along with membership forms and payment for dues. A few members of his campaign team went with him. PC Party president and acting executive director Don Moore called the police when party employees let him know about the situation. In the end, the police escorted Duffie into the office—alone—to drop off his documents. The party organization rejected his application to contest the nomination for being late. Duffie later brought a court case against the PC Party of New Brunswick for violating its formal rules. He lost.

After Duffie lost the court case, he sought the Liberal nomination in the same riding. Despite support from the Liberal riding association, the Liberal green-light committee rejected his application to run during the vetting process, in large part due to statements he made that were critical of Premier Gallant on social media.

Although the Carleton–York case is the most well documented, there were two other near-contested PC nominations. In Moncton Northwest, former party president and acting executive director Don Moore filed paperwork to run against incumbent PC MLA Ernie Steeves based on the perception that some Moncton Northwest PCs were unhappy with Steeves as their MLA.Footnote 13 According to one interviewee, central party actors met with Moore to convince him that it was not in his best interest to run against a sitting incumbent, since it could ruin his chances of running in the future (Interview 22). Then, the central and local organizations arranged a snap convention. According to a PC insider, Moore withdrew from the race because he knew he was not going to unseat an incumbent candidate without time to sign up his supporters as members (Interview 22). In Saint Croix, Cynthia Bartlett announced her interest in running for the nomination, but later long-time former MP Greg Thompson decided to run. Since Thompson won every election in the federal riding that includes Saint Croix from 1988 to 2008, many central and local PC insiders overwhelmingly viewed him as the best chance to win the riding. According to a Saint Croix PC familiar with the case, party insiders met with Bartlett to discourage her from running in part by highlighting the potential for other candidates to mount strong nomination campaigns. She withdrew before the convention because of this discouragement (Interview 49).

Ultimately, central party actors’ anti-competitive gatekeeping activities explain the four cases of near-contested nominations I examine in this section. These case studies illustrate not only the use of anti-competitive gatekeeping activities but also the reasons for and consequences of those anti-competitive gatekeeping activities in practice. They also highlight the reliance of central party actors on techniques such as discouragement, snap conventions and early conventions, rather than more powerful tools such as appointments or the leader's veto.

Discussion

In this article, I present a theory of gatekeeping that I build through an in-depth multi-method field study of candidate nominations for the 2018 New Brunswick election. I identify six observable implications of this theory and present evidence for each of them. I illustrate the existence and constraints of the norm of non-interference with interviews with party insiders. I present evidence on the role of district competitiveness, incumbency, intra-party disagreement and anti-competitive gatekeeping in shaping the probability of contested nominations through quantitative data on Liberal and PC nominations. Finally, I illustrate the motivations and mechanisms that produce anti-competitive gatekeeping through four case studies of near-contested nominations.

This article makes three main contributions. First, it synthesizes past research on candidate selection and field observations into a theory of gatekeeping in candidate selection. Second, it demonstrates the importance of anti-competitive gatekeeping for explaining why nominations go uncontested, even in competitive and safe ridings. Finally, it generates claims about intra-party disagreement and gatekeeping that are testable in future studies of candidate selection in other places, time periods and levels of government.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423922000385.