Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 January 2020

Letting  denote ‘would’ counterfactual conditionals like

denote ‘would’ counterfactual conditionals like

(A) If I had looked in my pocket, I would have found a penny and letting  denote ‘might’ counterfactual conditionals like

denote ‘might’ counterfactual conditionals like

(B) If I had looked in my pocket, I might have found a penny,

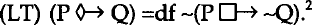

David Lewis’s thesis (LT) regarding the connection between these two types of conditionals is that

1 Thanks to John Carroll and David Lewis for helpful comments.

2 Lewis, D. Counterfactuals (Oxford: Basil Blackwell 1973), 2, 21-4Google Scholar

3 Inquiry (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press 1984), 145. Stalnaker writes: ‘I do not think that Lewis’s example is plainly false since the epistemic reading, according to which it’s true, seems to be one perfectly reasonable interpretation of it. I can also see the nonepistemic sense that Lewis had in mind, but I think that this sense can also be captured by treating might as a possibility operator on the conditional.’

4 Given some very plausible background assumptions (e.g., that your looking would not have produced a penny that you could have found).

5 Stalnaker takes ![]() to express a possibility that

to express a possibility that ![]() ; the ‘might’ in

; the ‘might’ in ![]() is ‘a possibility operator on the conditional’ (Inquiry, 145). How close Stalnaker’s view comes to (ET) depends upon what kind of possibility of

is ‘a possibility operator on the conditional’ (Inquiry, 145). How close Stalnaker’s view comes to (ET) depends upon what kind of possibility of ![]() he thinks

he thinks ![]() expresses. His suggestion is that ‘might, when it occurs in conditional contexts, has the same range of senses as it has outside of conditional contexts’ (143). Since Stalnaker thinks that ‘might’ most commonly expresses an epistemic possibility (143), his view is close to (ET); but since he thinks the range of possibilities ‘might’ can express also includes nonepistemic, and ‘quasi-epistemic’ possibilities (see 143-6), the exact relation his view bears to (ET) is quite complex.

expresses. His suggestion is that ‘might, when it occurs in conditional contexts, has the same range of senses as it has outside of conditional contexts’ (143). Since Stalnaker thinks that ‘might’ most commonly expresses an epistemic possibility (143), his view is close to (ET); but since he thinks the range of possibilities ‘might’ can express also includes nonepistemic, and ‘quasi-epistemic’ possibilities (see 143-6), the exact relation his view bears to (ET) is quite complex.

6 In ‘Epistemic Possibilities,’ The Philosophical Review 100 (1991) 581-605, I argue that assertions of the form, ‘It is possible that P,’ where the embedded P is in the indicative mood, are true if and only if (1) no member of the relevant community knows that P is false and (2) there is no relevant way by which members of the relevant community can come to know that P is false, where who is and who is not a member of the relevant community and what is and what is not a relevant way of coming to know are flexible matters that vary with context. In my paper, ‘“Might“ and “Would” Counterfactual Conditionals: The Epistemic Connection,’ I defend (ET) where the ‘epistemic possibilities’ are construed as I construe them in ’Epistemic Possibilities’: as those possibilities that the sentences described above typically express, and not, as they often are, as simply a matter of the speaker not knowing that P is false.

7 Lewis at least seems to intend this in Counterfactuals. In later work, he suggests that ’might’ counterfactual conditionals like (B) may be ambiguous between the reading according to which (LT) is true, and another reading. See D. Lewis, Philosophical Papers, Vol. II (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1984), 63-4. But since this other reading that Lewis allows is not an epistemic one (see 64, n.S), it cannot help with the present case, in which the truth of the ‘might’ conditional depends on what the speaker knows. This case demands an epistemic treatment of the ‘might’ conditional, a treatment which Lewis has yet to acknowledge the need for.

8 Lewis, D. ‘Probabilities of Conditionals and Conditional Probabilities,’ The Philosophical Review 85 (1976), 297.Google Scholar Lewis goes on to agree with Ernest Adams that ordinary indicative conditionals are an exception to the rule that assertability goes with subjective probability.