Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 January 2020

In what follows I propose to consider the relevance of Plato's early claim that his Forms are explanatory to the structure of, and several of the main arguments of, the Parmenides. The first section of the paper looks into some implications of separate existence, exploring connections between the criticism of separation and the conception of Forms as explanatory principles. I focus attention on what the Forms do not explain, and suggest that the burden of much of Parmenides’ criticism centers on that question. Part two deals with Plato's evidently changing stance on the issue of explaining the Forms themselves. The third section takes up passages from the Parmenides in support of the view that Plato came to believe that his Forms stood in need of the same sort of explanation as he had originally thought was required for sensory particulars. The discussion is largely exploratory, and the connections adumbrated are intended as guidelines for further investigation.

1 Contrast the tradition beginning with Aristotle (Met. 1078b30, 1086b2) which maintains that Plato took Socratic definitions and universals and gave them separate existence. If that were a correct description, the question “Why separate existence?” would make perfectly good sense. But . Aristotle viewed the Platonic theory through conceptual lenses that were the first to pick up a distinction between universal and particular as well as one between substance and non-substantial categories of being. His comments are critical rather than descriptive.

2 Aristotle's Physics Books I and II; translated by Charlton, W. (Oxford, 1970) p. 5.Google Scholar

3 “Forms and Explanation in the Phaedo”, Phronesis ( XXI (1976) ). Cherniss, apparently followed by Charlton (op. cit. p. 59), remarks that Aristotle's explanation of Parmenides' error is equivalent to the logical critique of Plato's, Sophist (Aristotle's Criticism of Presocratic Philosophy, New York (1971), p. 73).Google Scholar But the failure to distinguish between property and owner is corrected by the early theory of Forms. The second point Aristotle makes, however, was not clearly seen by Plato.

4 But that does not mean Aristotle thought that Plato's doctrine of Forms as ![]() in the Phaedo was an attempt to answer Parmenides. His own testimony indicates that he did not. What baffles Aristotle most about the account in the Phaedo is the oddity of positing Forms as sufficient

in the Phaedo was an attempt to answer Parmenides. His own testimony indicates that he did not. What baffles Aristotle most about the account in the Phaedo is the oddity of positing Forms as sufficient ![]() of generation and destruction (De Gen. et Corr. 335b9-16, Met. 991b3-9, 1080a2- 8) while at the same time denying them any efficacy in producing change (Met. 988a8-10, 98Bb2-4, 991a11, 992a24-26, 1079b14).

of generation and destruction (De Gen. et Corr. 335b9-16, Met. 991b3-9, 1080a2- 8) while at the same time denying them any efficacy in producing change (Met. 988a8-10, 98Bb2-4, 991a11, 992a24-26, 1079b14).

5 Cf. “Forms and Explanation in the Phaedo”.

6 Cf. Phaedo 101b1.

7 Met. 1086b6-7; cf. 997b5-8, 1033b19-29, 1040a8-9, 18-19, 1040b27-33, Z, 14.

8 In the Phaedo Plato does not use![]() and cognates in connection with the Forms, though he does use them to describe the condition of the soul in separation from the body (e.g., 67a1, c6, d4, d9). Separation is implicit, however, in the expression

and cognates in connection with the Forms, though he does use them to describe the condition of the soul in separation from the body (e.g., 67a1, c6, d4, d9). Separation is implicit, however, in the expression ![]() ,which is commonly used to depict the status of the Forms in the Phaedo. The frequent occurrence of

,which is commonly used to depict the status of the Forms in the Phaedo. The frequent occurrence of![]() in the Parmenides appears to signify an increasing interest on the part of Plato and his critics in that feature of the theory.

in the Parmenides appears to signify an increasing interest on the part of Plato and his critics in that feature of the theory.

9 Met. 1086b10, 1040b33, 997b7.

10 Met. 1038b34; Soph. El. 178b37; d. also Met. 990b33-991a8, 1079a30-1079b3.

11 The problem in sorting out the differences between (1) and (2) cannot therefore be summed up merely as a matter of distinguishing between predication and identity. See, for example, Taylor, A.E. “Parmenides, Zeno and Socrates”, Proc. Arist.Soc. N.S., XVI, (1915-16), p. 254.Google Scholar That distinction among others is in the very process of being drawn. The predication-identity dichotomy may even have the effect of blinding us to the conceptual mechanisms through which the distinction these philosophical categories are designed to illuminate actually evolved.

12 That is not to say that Plato never uses descriptive language in talking about his Forms or that when he does so, in contexts such as Symposium 211-212, for example, we may not receive the initial impression that the Forms are selfpredicational. Rather it is to say (1) that he would very likely not have done so with such abandon, had he previously considered the function of statements such as “The Beautiful is beautiful” and (2) that he is by no means committed to self-predication by his early theory — indeed, that the question could not have arisen for him within the context of the early theory of Forms.

13 I do not mean that self-predication is the only fallacy in the arguments of part one, but merely that that assumption might be exposed (and could therefore be confronted) by the question “in virtue of what ![]() is The Large itself large” (cf. 132a-b).

is The Large itself large” (cf. 132a-b).

14 The Sophist and other mature works of Plato indicate that he was on his way toward this necessary refinement of his theory.

15 See, for example, the following discussions: Robinson, R. Plato's Earlier Dialectic, Second Edition (Oxford, 1953)Google Scholar, Ch. IX; Hackforth, R. Plato's Phaedo (Cambridge, 1955)Google Scholar, Ch. XVI; Bluck, R.S. Plato's Phaedo(London, 1955)Google Scholar, Ch. 4, Appendix VI; Ross, W.D. Plato's Theory of Ideas(Oxford, 1951)Google Scholar, Ch. III; T.G. Rosen meyer, “Plato's Hypothesis and the Upward Path”, AJP (1960), pp. 393–407.

16 The sense in which the consequences of a hypothesis agree (or disagree) with one another (101d5) must be different from that in which something else, a thesis about causes, for example, agrees (100a5) with the hypothesis. The latter must be a stronger sense of ![]() , which is probably not technical in these passages.

, which is probably not technical in these passages.

17 Socrates’ objection to the ![]() at 101e is that they demand an account of the Forms before the theory and its consequences have even been fully stated. If told that A is the cause of B their response is to ask contentiously for the cause of A without regard for the philosophical implications of the original hypothesis. The account requested would be an explanation. But Plato does not mean by

at 101e is that they demand an account of the Forms before the theory and its consequences have even been fully stated. If told that A is the cause of B their response is to ask contentiously for the cause of A without regard for the philosophical implications of the original hypothesis. The account requested would be an explanation. But Plato does not mean by ![]() a definition (Bluck, op.cit., p. 169) or a proof that the hypothesis is true (Robinson, op. cit., p. 136).

a definition (Bluck, op.cit., p. 169) or a proof that the hypothesis is true (Robinson, op. cit., p. 136).

18 Aristotle's comment at Metaphysics 990a34-b8 (1078b32-1079a4) implies that the Forms are no less in need of explanation than the particulars they have been introduced to explain. “For the Forms are almost equal to ― or no less than―those things which, when they sought to explain them, they proceeded from them to the Forms”.

19 Cf. 66a, 67b, 78d, 79d, 80b.

20 I do not mean to minimize the importance for Plato of a teleological explanation. Socrates’ interest in teleology was apparent in the Phaedo, where he expressed disappointment in Anaxagoras’ doctrine of ![]() as the cause of all things (97c-99d). My chief concern, however, is to establish a sense in which the Good is not explanatory of the Forms in the Republic.

as the cause of all things (97c-99d). My chief concern, however, is to establish a sense in which the Good is not explanatory of the Forms in the Republic.

21 The ![]() Socrates is referring to resulted from the capacity of sensory particulars to admit opposite predicates, hence from what had appeared to be their makeup as “mixtures” of opposites. Cf. “Forms and Explanation in the Phaedo”.

Socrates is referring to resulted from the capacity of sensory particulars to admit opposite predicates, hence from what had appeared to be their makeup as “mixtures” of opposites. Cf. “Forms and Explanation in the Phaedo”.

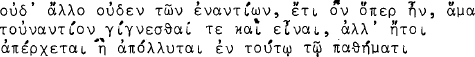

22 129c2-3. Cf. Socrates’ categorical statement at Phaedo 102e7-103a2:  At Philebus 15a-e statements in which Forms are the subjects of discourse are still considered troublesome and worthy of serious consideration.

At Philebus 15a-e statements in which Forms are the subjects of discourse are still considered troublesome and worthy of serious consideration.

23 The implications of mixture among Forms extend further. The theory of separately existing Forms of course did not rule out relationships between Forms and particulars (participation), nor did it rule out relationships among the Forms themselves (Phaedo 105a). But the separateness of a Form, its most definitive feature, does seem incompatible with mixture. How can traits such as ![]() which are by definition incompatible with mixture between Forms and sensory particulars, be accommodated to mixture among the Forms themselves? Many have thought they cannot, but Plato never stopped referring to his Forms in this way even after he wrote the Sophist (cf. Phil. 59c, Tim. 27d, 35a, 37a-b, 51e), in which the mixing of Forms is acknowledged to be necessary for intelligible discourse. One of the tasks of the Sophist may well be to show how mixture among the Forms does not cancel those traits definitive of the Form as a separate existent. What remains after the accommodation is another story.

which are by definition incompatible with mixture between Forms and sensory particulars, be accommodated to mixture among the Forms themselves? Many have thought they cannot, but Plato never stopped referring to his Forms in this way even after he wrote the Sophist (cf. Phil. 59c, Tim. 27d, 35a, 37a-b, 51e), in which the mixing of Forms is acknowledged to be necessary for intelligible discourse. One of the tasks of the Sophist may well be to show how mixture among the Forms does not cancel those traits definitive of the Form as a separate existent. What remains after the accommodation is another story.

24 Parmenides calls it a hypothesis at 136a4 and speaks of the implications that follow from it ![]() At 128d-e the method of drawing out the implications of a hypothesis is attributed to Parmenides’ antagonists, and Zeno claims to have followed the same method in his treatise.

At 128d-e the method of drawing out the implications of a hypothesis is attributed to Parmenides’ antagonists, and Zeno claims to have followed the same method in his treatise.

25 The specific antinomies produced would no doubt depend on the concept examined, but the implication seems to be that some antinomies could be deduced from any hypothesis in which a Form is subject. At Philebus 15a “man”, “ox”, “the beautiful”, and “the good” are mentioned as yielding the conclusion that the one is many and the many one. The paradox of the one and many is said to be involved in every statement ever uttered (15d6).

26 For this reason the debate over whether or not, in fact or in Plato's mind, the deductions are “valid” seems to me unpromising. Nor do I think, along with Cornford (Plato and Parmenides, London (1939), pp. 110–112), that Plato is simply trying to draw attention to the ambiguity of the concepts “one” and “being”. His point must be that, as things stand, there is nothing to guide us in construing the meaning, and hence deducing the implications, of the sample hypothesis. That is, given the limitations of the early theory of Forms, anything will do. It is crucial to Plato's purpose that all the consequences be accepted, because from the very fact that contradictory consequences issue from both a proposition and its negation we are compelled to reflect on its meaning. That is not the same as saying that because its implications are absurd the proposition is illegitimate (cf. Ryle, “Plato's Parmenides”, in Studies in Plato's Metaphysics,ed. Allen, R.E. London (1965) p. 123).Google Scholar

27 F.M. Cornford wrote, “Since every definition is a statement about a Form entirely in terms of other Forms, we may suspect that the preliminary exercise needed before any definition is undertaken will have some bearing on that question of the relation of Forms among themselves” (op. cit., p. 104).

28 The question (“in virtue of what…’) is raised in the Sophist in the process ∼f sorting out the “greatest kinds”. Note, for example, the explanatory force of ![]() with the accusative and

with the accusative and ![]() at 255e5, 256a1, 256b1-4, 256d11-e3, 259a7. The fact that

at 255e5, 256a1, 256b1-4, 256d11-e3, 259a7. The fact that ![]() drops out as an explanatory term in these contexts may indicate that Plato has become more aware of the logical nature of his inquiry. The complexities of charting out the interrelationships among Forms seem to have been appreciated by Plato. Such a program necessitated an investigation into the possibilities for combination among the Forms (253-254d) as well as the analysis of statements as a “weaving together” of subject and predicate (262-263), all of this necessary groundwork for the new methodology of division and subsequent attempts to define the Forms.

drops out as an explanatory term in these contexts may indicate that Plato has become more aware of the logical nature of his inquiry. The complexities of charting out the interrelationships among Forms seem to have been appreciated by Plato. Such a program necessitated an investigation into the possibilities for combination among the Forms (253-254d) as well as the analysis of statements as a “weaving together” of subject and predicate (262-263), all of this necessary groundwork for the new methodology of division and subsequent attempts to define the Forms.

29 I cannot believe that Plato meant the absurdity that the Form Knowledge itself knows the other Forms. That reading (also self-predicational) makes the Form Knowledge the most perfect knower, whereas at 134c it is the god who is said to know the Forms. The interpretation given above makes better sense of the passage, even though the uses of ![]() at 134b6 and 134b11 are not strictly parallel.

at 134b6 and 134b11 are not strictly parallel.

30 Passages frequently cited as evidence of self-predication in the early theory are Phaedo 74d, 100c, 103e, Symposium 211-212, Protagoras 330c-e, Hippias Major 292e, Lysis 217d.

31 I have assumed throughout that ![]() are, for all practical purposes, synonymous. If they are not, we shall have to say that while Socrates has examined the

are, for all practical purposes, synonymous. If they are not, we shall have to say that while Socrates has examined the ![]() of his hypothesis, he has failed to consider its

of his hypothesis, he has failed to consider its ![]() It makes better sense to say that he has not examined the consequences

It makes better sense to say that he has not examined the consequences ![]() of his hypothesis thoroughly enough and that he has failed to treat particular statements about the Forms as separate hypotheses.

of his hypothesis thoroughly enough and that he has failed to treat particular statements about the Forms as separate hypotheses.

32 A similar version of this paper was presented at a workshop in Greek philosophy at the University of Alberta in November 1974. I owe thanks to many of the participants for their helpful comments.