Background

Functional neurological disorder (FND) is a common cause for disabling neurological symptoms, including altered awareness, motor, and sensory changes. Reference Edwards and Bhatia1 Many terms are used to describe this disorder: psychogenic, conversion, somatization, nonorganic, hysteria, shell shock, and medically unexplained. Reference Edwards and Bhatia1–Reference Linden and Jones4 The criteria for diagnosis have shifted from a diagnosis of exclusion to a diagnosis emphasizing positive signs and other features. Reference Abdelnour and El-Nagi5,Reference Gasca-Salas and Lang6 Multiple diagnostic criteria have been proposed over the years for various types of functional symptoms (psychogenic non-epileptic attack [PNEA], functional movement disorders), resulting in significant heterogeneity in how the diagnosis is made. Reference Gasca-Salas and Lang6

Due to the lack of demonstrable structural abnormalities, a common misconception among care providers is that FND is benign. A systematic review examining the prognosis of FND found that a majority of patients continue to experience symptoms and disability years after their initial presentation, often with morbidity equal to or greater than that of other neurological conditions, although the included studies likely underestimate recovery potential, as patients did not receive treatment. Reference Gelauff, Stone, Edwards and Carson7 Thus, there exists a considerable need to investigate treatment approaches for FND.

There is evidence for multidisciplinary treatment of FND with a symptom-based approach. Reference Jacob, Smith and Jablonski8,Reference Demartini, Batla, Petrochilos, Fisher, Edwards and Joyce9 Multidisciplinary teams often include specialists from neurology, psychiatry, psychology, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech and language pathology, and chronic pain. Reference Jacob, Smith and Jablonski8,Reference Demartini, Batla, Petrochilos, Fisher, Edwards and Joyce9 However, what has not been clearly defined is the preferred setting for delivery of treatment, whether it be as an inpatient in acute, psychiatric, or rehabilitation wards, or provided through outpatient clinics. In the current landscape of FND treatment, patients are seen and managed in outpatient specialty clinics, when available. Reference Cock and Edwards10 Unfortunately, resources for the treatment of FND are frequently limited, and globally, many patients do not have access to specialists for diagnosis or treatment. Reference Cock and Edwards10 Inpatient treatment of FND, especially in the case where admission is elective, is uncommon due to a severe lack of resources. In some centers, patients may be admitted to the hospital if outpatient treatment fails to improve symptoms, if disability is high, or if the symptoms present acutely requiring further investigation and intensive treatment. Reference Saifee, Pareés and Kojovic11 Of particular interest are the outcomes of patients requiring inpatient care due to severity of symptoms, as this subset of FND patients may have higher disability, risk of iatrogenic harm, and incur a greater cost to health care systems. Reference Saifee, Pareés and Kojovic11

Inpatients with FND can be divided into two distinct subgroups: (1) patients who present acutely after developing symptoms and (2) patients admitted electively for intensive inpatient treatment of chronic symptoms. The aim of this scoping review was to understand the clinical characteristics of FND patients admitted and treated in the hospital setting. Additionally, this review was intended to better delineate which patient subgroups may benefit from inpatient treatment. This is necessary for the appropriate allocation of limited resources, as well as to maximize the recovery potential of patients. Given the well-known heterogeneity within treatment approaches, direct comparison between programs was not possible. Thus, the purpose of this paper was to understand and not to compare individual treatment programs. Furthermore, the ideal inpatient setting for delivery of therapy, whether it be an acute care unit, psychiatric unit, or rehabilitation unit, is unknown.

Methods

A scoping review was done to map the emerging research on inpatient functional treatment, reveal methodological gaps, and identify areas for future research. Reference Arksey and O’Malley12 This review included the following five key phases: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. Reference Arksey and O’Malley12 This framework was used to answer the following research questions:

-

1. What are the characteristics of adult patients who require admission to the hospital for functional neurological symptoms?

-

2. What interventions are provided for inpatients with functional neurological symptoms?

-

3. What are the outcomes for inpatients with acute and chronic presentations of functional neurological symptoms?

Search Strategy

Relevant healthcare databases were chosen for the initial search strategy in consultation with a research librarian for the scope of this review. A search strategy was developed after a preliminary iterative search of the databases. The initial search of databases was conducted on January 22, 2019 in PubMed (1946–Present), Medline (1946–Present), CINAHL (1981–Present), and PsychINFO (1987–Present). A hand search of relevant review and expert articles was undertaken in February 2019. Given the diverse terms used to describe functional symptoms, both historically and across disciplines, a broad search strategy was employed. The terms functional movement disorder, functional symptoms, conversion disorder, conversion, psychogenic, and somatoform were combined with the following appropriate MeSH terms: inpatient, hospital, ward, acute care, neurology, rehabilitation, psychiatry, physiatry, physiotherapy, therapy, and behavioral therapy. Grey literature searches were conducted through relevant websites (e.g. neurosymptoms.org, fndhope.org), relevant conference proceedings, and Google Advanced Search. An a priori decision was made to only search the first 100 Google results given the time necessary to review each result. We also utilized Mendeley Reference Management “Suggest” function based on uploaded articles. The search was limited to French and English language articles only. No date restrictions were applied.

Eligibility Criteria

Articles were included in the final review if they included data on adults (18+ years) who were admitted with functional neurological symptoms to an inpatient care setting. Articles that focused on the care of those with PNEA or treatment delivered exclusively in an outpatient setting were excluded.

Study Selection

All citations were imported to the Mendeley Citation Management, and duplicates were removed. All potentially relevant citations were independently screened by the two authors by title and abstract. Full-text articles were screened by the two authors to ensure criteria for inclusion were met. Meetings between the two authors were held regularly to discuss differences or ambiguity in the application of inclusion criteria during selection.

Data Extraction

A standardized form was created to extract data from included studies. Detailed information, including author, title, publication year, country of origin, methodology, sample size, institutional setting, admission type, characteristics of admitted patients, interventions, outcomes, follow-up, identified gaps, challenges, and limitations, were obtained upon the second reading of the articles. Data extraction was performed on all eligible studies by both investigators.

Data Synthesis

Given the heterogeneity of the included articles, a narrative synthesis was used to organize and summarize the data. Reference Popay, Roberts and Sowden13 Papers were grouped according to the duration of symptoms prior to admission, with symptoms present for less than 3 months being considered acute presentations and longer than 3 months being chronic presentations. Publications were reported by the admission setting and admission type. The quality of included studies was not assessed, as this is not typical for a scoping review.

Results

Search and Selection

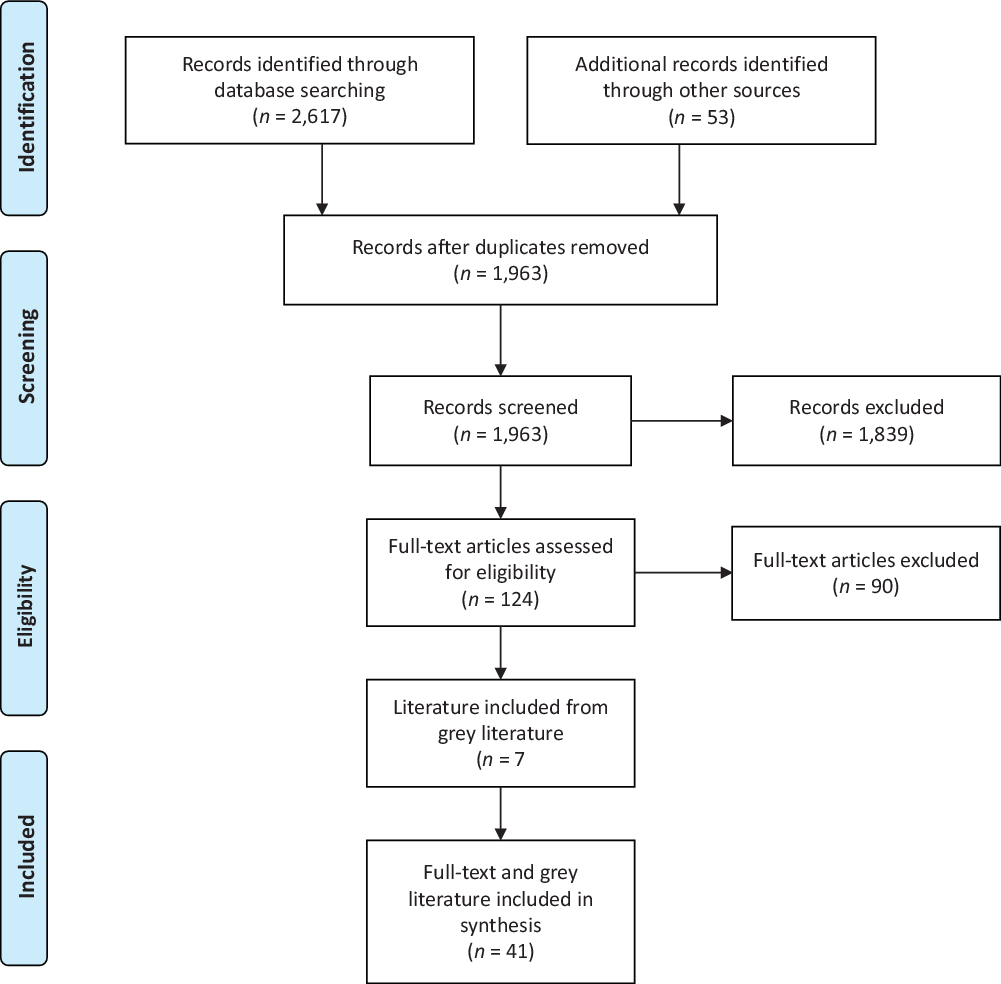

In total, the search strategy identified 2670 citations. After duplicates were removed, 1963 citations were screened using the inclusion criteria. The title and abstract screen resulted in the retrieval of 124 articles for full-text review. A total of 34 full-text articles met criteria for the final synthesis (Figure 1). After the review of relevant grey literature, seven abstracts were selected from conference proceedings. Attempts were made to contact the authors to obtain supportive evidence and other data relevant to the research questions.

Figure 1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram indicated the number of citations included at each stage of review.

General Characteristics

Full-text studies (Tables 1–3) and available grey literature (Table 4) were organized by symptom onset, admission type, and study design. The earliest published study of inpatient treatment of functional patients was in 1970. Reference Trieschmann, Stolov and Montgomery37 The majority of studies were published between 2010 and 2019 (n = 16). An evolution in terms used to describe functional symptoms has occurred over time. The term “conversion” was used most frequently (n = 18) by studies in this review. More recently, the term “functional” has gained traction in the inpatient literature. Since 2014, there were 13 studies that used the term. Other terminologies included psychogenic (n = 3), hysteric (n = 2), and nonorganic (n = 1).

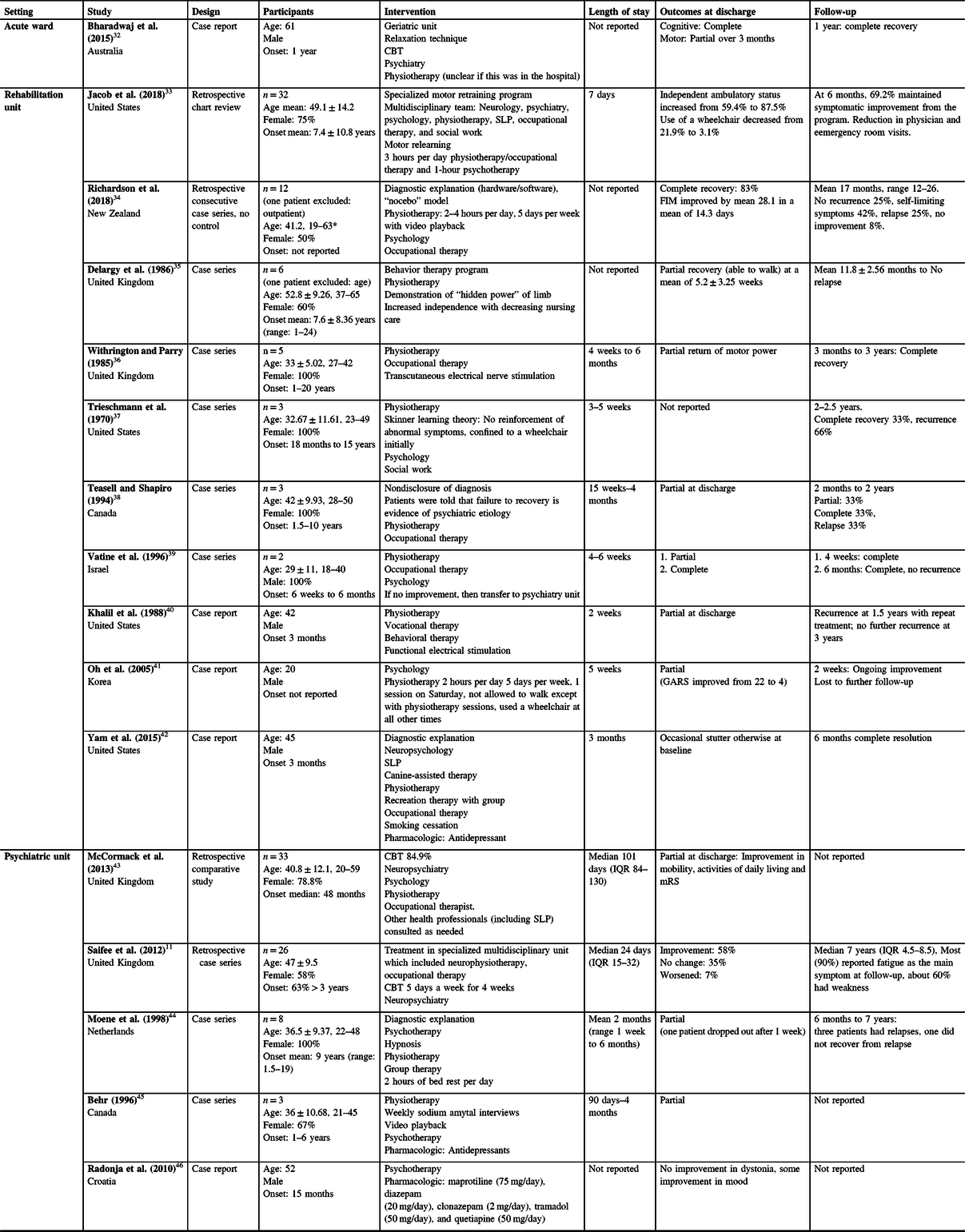

Table 1: Acute and chronic presentations

Acute and chronic presentations of FND. Study characteristics, characteristics of inpatients, interventions, and outcomes, organized by the setting of inpatient admission. FIM = Functional Independence Measure; MAOi = monoamine oxidase inhibitor; MRMI = Modified Rivermead Mobility Index; PNEA = psychogenic non-epileptic attacks; SF-12 = 12-Item Short Form Survey; TCA = tricyclic antidepressant. *Unable to calculate the standard deviation with data provided in the study.

Table 2: Acute presentation

Acute presentations of FND. Study characteristics, characteristics of inpatients, interventions, and outcomes, organized by the setting of inpatient admission. ADL = activities of daily living; ED = emergency department; FAST = face arm speech test; IV = intravenous; MRC = Medical Research Council; PNEA = psychogenic non-epileptic attacks; PRN = as needed; SLP = speech and language pathology; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Table 3: Chronic presentation

Chronic presentations of FND. Study characteristics, characteristics of inpatients, interventions, and outcomes, organized by the setting of inpatient admission. CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; FIM = Functional Independence Measure; GARS = Gait Abnormality Rating Scale; IQR = interquartile range; SLP = speech and language pathology. *Unable to calculate the standard deviation with data provided in the study.

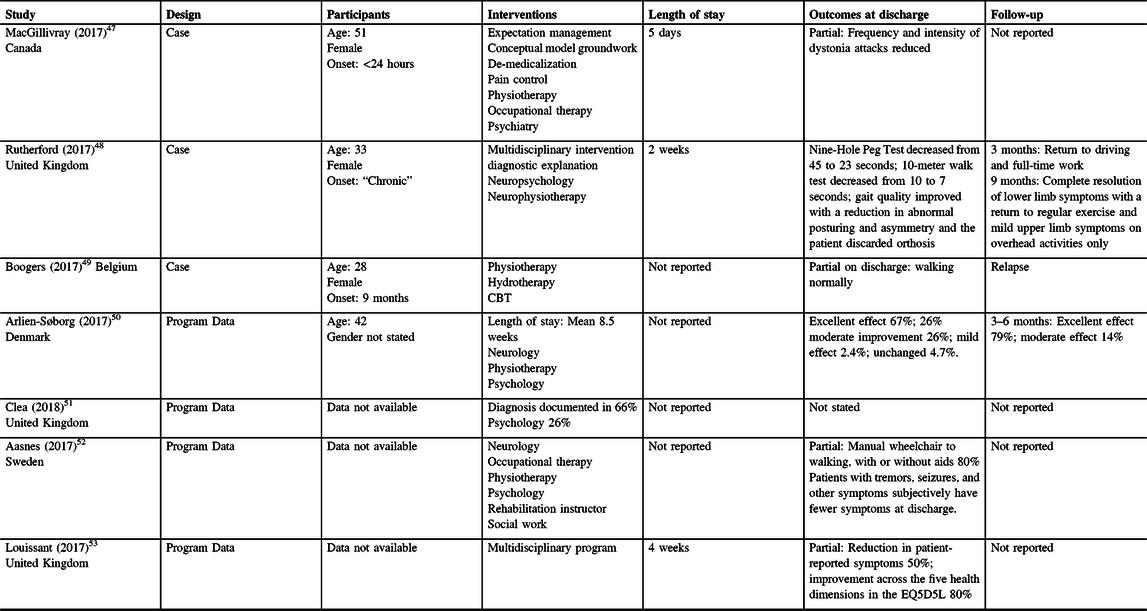

Table 4: Grey literature

Grey literature characteristics of inpatients, interventions, and outcomes. (CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; EQ5D5L = EuroQol-5D, an instrument for measuring quality of life).

Most studies were located in the United States (n = 13) and the United Kingdom (n = 6). Fifty percent of studies were case series. The majority of studies were performed on rehabilitation units (n = 16); other units included medical/surgical wards or psychiatric units. Most studies included patients who were admitted electively (n = 27) from outpatient specialty clinics or from referral from general practitioners.

Patient Characteristics

Thirty-four studies addressed baseline patient characteristics (Tables 1–3). A total of 458 patients with FND were described, 66% of whom are female and 34% are male. The age range of all patients was 18–70 years, with a pooled mean of 40.6 years.

All 34 included studies described the type of functional symptoms leading to admission for inpatient treatment. There did not appear to be differences in the presenting symptoms of patients with acute onset compared to those with chronic symptoms. The most common functional symptoms were motor symptoms, including weakness, dystonia, tremor, and gait disorder, present in 350 of 458 patients. Additional functional symptoms in order of frequency were: PNEA (n = 27), sensory (n = 17), urinary (n = 12), cognitive (n = 6), visual (n = 4), speech (n = 2), and hearing loss (n = 2). The authors specifically described 80 patients presenting with multiple functional symptoms, with many studies not providing details beyond the most prominent symptom. The most commonly discussed comorbid symptoms include pain (53 patients) and fatigue (6 patients).

Only nine studies specifically described psychiatric comorbidity, beyond a diagnosis of conversion disorder or somatization disorder. Reference Dickes20,Reference O’Neal and Dworetzky23,Reference Silver27,Reference Bharadwaj, Lee and Moffat32,Reference Jacob, Kaelin, Roach, Ziegler and LaFaver33,Reference Vatine, Milun and Avni39,Reference Yam, Rickards, Pawlowski, Harris, Karandikar and Yutsis42–Reference Moene, Hoogduin and Dyck44 Comorbid psychiatric diseases included depression (30 patients), PTSD (30 patients), anxiety (23 patients), ADHD (1 patient), and specific phobia (1 patient). In many larger trials, patients with comorbid psychiatric disease were excluded.

Thirty-one studies (Tables 1–3) discussed the duration of functional symptoms that patients reported prior to being admitted for treatment, with a range of less than 24 hours to 15 years reported. Seven larger studies included a total of 206 patients with both acute and chronic symptoms, with a range of less than 1 day to 15 years (Table 1). In a prospective case series of patients receiving inpatient treatment, Matthews et al. (2016) divided 35 patients into 21 patients presenting with acute symptoms (1 day to 1 month), and 14 patients admitted with chronic symptoms (2 months to 10 years). Reference Matthews, Brown and Stone14 Jordbru et al. (2014) enrolled 60 patients with a mean duration of symptoms of 9.5 months in a randomized, controlled trial of a 3-week inpatient rehabilitation program.Reference Jordbru, Smedstad, Klungsoyr and Martinsen16 Shapiro and Teasell (2004) described 9 patients with symptoms for less than 2 months and 30 patients with symptoms greater than 6 months in a case series. Reference Shapiro and Teasell17 Fahn and Williams (1988) simply stated that 21 patients in a case series had a duration of symptoms between less than 1 month and 15 years. Reference Fahn and Williams15

Patient Characteristics: Acute Presentations

Eleven studies described a total of 115 patients with acute presentations of FND admitted to the hospital, 67% of whom were female (Table 2). The pooled mean age was 46.9 years. Among studies describing patients with acute presentations, 10 studies provided details on the duration of symptoms for individual patients, with a mean duration of 5.2 ± 7.8 days and a median of 1 day. Reference Letonoff, Williams and Sidhu22–Reference Gill31 Gargalas et al. (2017) reported a mean of 13.3 hours for 98 patients admitted to a hyperacute stroke ward with functional stroke symptoms. Reference Gargalas, Weeks and Khan-Bourne21

All 115 patients in all 11 studies experienced motor symptoms. Additional symptoms included: sensory (n = 6), cognitive (n = 3), visual (n = 3), speech (n = 2), and urinary (n = 1). In addition to neurological symptoms, patients with acute symptom onset also experienced pain (n = 5) and fatigue (n = 1). Reference Gargalas, Weeks and Khan-Bourne21,Reference Letonoff, Williams and Sidhu22,Reference Atan, Seçkin and Bodur25,Reference Silver27,Reference Ness28,Reference Hersen, Matherne, Gulliock and Harbert30 Only two studies specifically described patients having psychiatric comorbidities, in both cases generalized anxiety disorder. Reference O’Neal and Dworetzky23,Reference Silver27

Patient Characteristics: Chronic Presentation

Sixteen studies described a total of 136 patients with chronic FND symptoms admitted to the hospital (Table 3). Of those patients with chronic FND symptoms, 70% were female, and the pooled mean age for all patients was 43.7 years. Eleven studies reported the duration of symptoms of specific patients prior to admission, with a mean duration of 5.8 ± 6.4 years and a median of 3 years. Reference Bharadwaj, Lee and Moffat32,Reference Delargy, Peatfield and Burt35–Reference Khalil, Abdel-Moty, Asfour, Fishbain, Rosomoff and Rosomoff40,Reference Yam, Rickards, Pawlowski, Harris, Karandikar and Yutsis42,Reference Moene, Hoogduin and Dyck44–Reference Radonja, Ružić and Grahovac46 Larger elective admission studies presented the duration of symptoms using alternative intervals. Thirty-two patients with a mean duration of symptoms of 7.4 years were described in a retrospective chart review by Jacob et al. (2018). Reference Jacob, Kaelin, Roach, Ziegler and LaFaver33 Fewer details regarding the duration of symptoms were given by Saifee et al. (2012), simply that 63% of the 26 patients responding to a survey after inpatient admission had a duration of symptoms greater than 3 years. Reference Saifee, Pareés and Kojovic11 McCormack et al. (2014) reported a median duration of 48 months in 33 patients. Reference McCormack, Moriarty and Mellers43

All patients in the 16 studies experienced motor symptoms. Additional symptoms included: PNEA (n = 6), sensory (n = 4), cognitive (n = 3), speech (n = 2), urinary (n = 1), and dysphagia (n = 1). Additionally, some studies described patients experiencing pain (n = 6) and fatigue (n = 1). Seven studies specifically described patients with psychiatric comorbidities, which included: major depressive disorder (n = 5), post-traumatic stress disorder (n = 3), generalized anxiety disorder (n = 2), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (n = 1), and a specific phobia (n = 1). Reference Bharadwaj, Lee and Moffat32,Reference Jacob, Kaelin, Roach, Ziegler and LaFaver33,Reference Yam, Rickards, Pawlowski, Harris, Karandikar and Yutsis42–Reference Radonja, Ružić and Grahovac46

Interventions

Thirty-three studies broadly discussed the types of interventions given to patients while admitted to the hospital (Tables 1–3). The most common types of intervention included physiotherapy (n = 29) and psychotherapeutic strategies (n = 27). Other common interventions included occupational therapy (n = 18), psychiatry (n = 15), antidepressant medications (n = 6), speech and language pathology (n = 3), transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and electromyography biofeedback (n = 5), recreation therapy (n = 2), hypnosis (n = 2), and confinement to a wheelchair when not in therapy (n = 2). Two studies described behavioral therapy strategies in which patients were told that failure to recover was proof that their symptoms were psychological in origin, thus providing motivation for recovery. Reference Shapiro and Teasell17,Reference Teasell and Shapiro38 Isolated studies described the use of placebo, Reference Fahn and Williams15 canine therapy, Reference Yam, Rickards, Pawlowski, Harris, Karandikar and Yutsis42 sodium amytal with video playback, Reference Behr45 positive reinforcement for improvement, Reference Dickes20 and daily bed rest. Reference Moene, Hoogduin and Dyck44 Only seven studies specifically discussed diagnostic explanation as a therapeutic strategy. Reference Matthews, Brown and Stone14–Reference Jordbru, Smedstad, Klungsoyr and Martinsen16,Reference O’Neal and Dworetzky23,Reference Richardson, Isbister and Nicholson34,Reference Yam, Rickards, Pawlowski, Harris, Karandikar and Yutsis42,Reference Moene, Hoogduin and Dyck44

Multidisciplinary approaches were utilized in 26 studies, with various combinations of specialties, including psychology, psychiatry, neurology, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech and language pathology, and recreation therapy often described, although not always specifically labeled as a multidisciplinary team.

Treatment elements and disciplines delivered did not differ significantly based on the setting of admission or whether patients were admitted with chronic or acute symptoms. Physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and multidisciplinary teams were more commonly utilized for patients admitted to neurology and rehabilitation, whereas pharmacologic treatments for mood were more commonly used in inpatient psychiatry settings.

Twenty-two studies reported on the length of stay, with a total of 303 patients described. The pooled mean duration of inpatient admission was 24.4 days, with a range of 1.54–180 days. When comparing patients with acute symptoms to those with chronic symptoms, patients admitted with acute symptoms had much shorter lengths of stay (pooled mean 2.9 days) compared to those admitted with chronic symptoms (pooled mean 27.8 days). Longer durations of stay are described in psychiatric admissions (89.8 days), followed by rehabilitation admissions (20.3 days) and inpatient neurology (6.3 days).

Outcomes

A large number of case studies and case series commented on the reversal of symptoms or attainment of independence as qualitative measures of outcomes. Only 10 studies captured health domains, such as degree of disability, cognitive, emotional, and quality of life with specific tools. Reference Saifee, Pareés and Kojovic11,Reference Matthews, Brown and Stone14,Reference Jordbru, Smedstad, Klungsoyr and Martinsen16,Reference Speed19,Reference Bharadwaj, Lee and Moffat32–Reference Richardson, Isbister and Nicholson34,Reference Oh, Yoo and Yi41–Reference McCormack, Moriarty and Mellers43 Degree of disability was most commonly captured with the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) (n = 3) Reference Matthews, Brown and Stone14,Reference Bharadwaj, Lee and Moffat32,Reference Richardson, Isbister and Nicholson34 and Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) (n = 2). Reference Jordbru, Smedstad, Klungsoyr and Martinsen16,Reference Jacob, Kaelin, Roach, Ziegler and LaFaver33 Impact on quality of life was assessed using the health-related quality of life scale in two studies. Reference Richardson, Isbister and Nicholson34,Reference Oh, Yoo and Yi41

Many studies reported partial or complete resolution of symptoms after hospitalization. Thirty-nine patients (8%) were reported to have no change or worsening of symptoms after hospitalization. Reference Saifee, Pareés and Kojovic11,Reference Matthews, Brown and Stone14,Reference Shapiro and Teasell17,Reference Heruti, Reznik, Adunski, Levy, Weingarden and Ohry18,Reference Yam, Rickards, Pawlowski, Harris, Karandikar and Yutsis42,Reference Moene, Hoogduin and Dyck44,Reference Behr45 Of those who did not improve, the authors cited premorbid psychiatric diagnosis, Reference Saifee, Pareés and Kojovic11,Reference Heruti, Reznik, Adunski, Levy, Weingarden and Ohry18,Reference Moene, Hoogduin and Dyck44,Reference Behr45 long duration of symptoms, Reference Saifee, Pareés and Kojovic11,Reference Yam, Rickards, Pawlowski, Harris, Karandikar and Yutsis42 or attrition Reference Matthews, Brown and Stone14 as likely factors for poor outcome. Among patients admitted with chronic symptoms, 8.7% had no change or worsened during hospitalization. All of these patients were admitted to psychiatric units. Reference Saifee, Pareés and Kojovic11,Reference Radonja, Ružić and Grahovac46 There were no reported cases of patients worsening or remaining at their pretreatment level of disability in the acute onset group; however, this must be interpreted cautiously given the implicit reporting bias of published case reports and case series.

The follow-up period after inpatient stay was reported between 2 weeks and as long as 8.5 years, although most studies followed patients within 1 year of treatment. Follow-up symptoms were described in a total of 78 chronic patients (follow-up pooled mean 12.7 months), 14 acute patients (follow-up mean 18.0 months, median 8 months), and 60 unspecified patients (follow-up pooled mean 13.2 months). Reference Saifee, Pareés and Kojovic11,Reference Jordbru, Smedstad, Klungsoyr and Martinsen16,Reference Speed19,Reference Letonoff, Williams and Sidhu22–Reference Atan, Seçkin and Bodur25,Reference Ness28,Reference Bharadwaj, Lee and Moffat32–Reference Yam, Rickards, Pawlowski, Harris, Karandikar and Yutsis42,Reference Moene, Hoogduin and Dyck44 A total of 16 chronic patients (18% of patients with reported follow-up) had a recurrence of symptoms in the follow-up period ranging from 1 month to 2.5 years. Reference Richardson, Isbister and Nicholson34,Reference Trieschmann, Stolov and Montgomery37,Reference Teasell and Shapiro38,Reference Khalil, Abdel-Moty, Asfour, Fishbain, Rosomoff and Rosomoff40,Reference Moene, Hoogduin and Dyck44 Jacob et al. (2018) reported eight patients that either had no change in symptoms or worsening symptoms at 6 months, but did not distinguish how many of these patients were relapses or non-responders. Reference Jacob, Kaelin, Roach, Ziegler and LaFaver33 None of the 14 acute patients in which follow-up was reported had relapses. Reference Letonoff, Williams and Sidhu22–Reference Atan, Seçkin and Bodur25,Reference Ness28 None of the patients with duration of symptoms not clearly specified had reported relapses. Reference Jordbru, Smedstad, Klungsoyr and Martinsen16,Reference Speed19 Notably, reported relapses emphasized motor symptoms.

An alternate diagnosis was rarely reported in the inpatient literature. Heruti et al. (2002) found four patients who did not improve met criteria for malingering. Reference Heruti, Reznik, Adunski, Levy, Weingarden and Ohry18 Thirty-two of 68 (47%) patients in Gargalas et al. (2017) had comorbid psychiatric diagnoses (depression and stress-related conditions) upon follow-up of general practitioner records, in addition to functional symptoms. Reference Gargalas, Weeks and Khan-Bourne21

Discussion

We used a narrative synthesis framework to interpret the data given the heterogeneity of the included literature. Consistent with previous reviews, patients with functional symptoms who required admission to hospital were predominantly female. Reference Tsui, Deptula and Yuan2 We found that the majority (76%) of patients admitted to the hospital had functional motor symptoms. When comparing acute to chronic onset of symptoms, we found that acute presentations were older (46.9 vs. 43.7 years) and had a higher representation of men (33% vs. 30%).

In our review of the literature, we found that no study of either patients with acute or chronic FND symptoms explicitly gave reason or provided criteria for admission to the hospital. Most studies described patients being admitted electively with functional neurological symptoms after the diagnosis is made in an outpatient specialty clinic, particularly those describing patients with chronic symptoms. Elective admissions were more likely to have symptoms for greater than 1 month, but the exact criteria for admission were not explicitly described beyond the presence of functional symptomatology and the patient being agreeable to admission.

Recently, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) has made significant revisions to the diagnostic criteria for FND, such as including positive clinical findings on physical examination, removal of identification of underlying stressors, and eliminating the need to rule out malingering or organic disease. Reference Abdelnour and El-Nagi5 Importantly, the addition of positive clinical findings on examination requires adoption and expert performance of a validated physical examination and consistent reporting of findings. Many studies included in this review did not specify criteria the patient met or which clinical findings best supported the diagnosis of FND. Given the prevalence of functional symptoms in inpatient practice and the need for larger scale randomized trials, validated diagnostic tools and a severity scale would be of significant benefit to advance research on effective treatment.

The evolution of terminology describing functional symptoms in the literature reflects the changes in the DSM-V. Reference Tsui, Deptula and Yuan2 Historically, functional symptoms have been viewed as psychopathology, either as hysteria or conversion of psychological complaints to somatic symptoms. Reference Tsui, Deptula and Yuan2 In this review of patients admitted with functional symptoms, we found that only 26% of studies described psychiatric comorbidity, with only 19% of included patients having diagnosed psychiatric comorbidity. The assumption that neurologic symptoms are a result of psychiatric illness is echoed throughout the literature; however, exploration of comorbid psychiatric conditions was not adequately captured in the included studies to comment on the need for psychiatric intervention for admitted patients. Reference Tsui, Deptula and Yuan2,Reference Moene, Hoogduin and Dyck44,Reference Behr45 Results of psychotherapeutic intervention in this review are mixed, but very few studies included tools that would capture the benefit of psychiatric intervention. Reference Jordbru, Smedstad, Klungsoyr and Martinsen16,Reference Bharadwaj, Lee and Moffat32,Reference Jacob, Kaelin, Roach, Ziegler and LaFaver33,Reference Yam, Rickards, Pawlowski, Harris, Karandikar and Yutsis42 Admission to a psychiatric unit had a higher use of pharmacologic treatments and, generally, had a longer length of stay, with similar mobility outcomes to other settings. There may be a subset of patients with functional neurological symptoms who will benefit more from psychological intervention than others, but this question requires further investigation.

The literature from the 1970s until now demonstrates an evolution from a paternalistic model where the diagnosis was not discussed and privileges were earned to a shared clinical diagnosis and treatment, with an increasing emphasis on self-managed care. Previous deceptive approaches reinforce the misconception that patients are “faking” and that “saving face” allows acceptance. Reference Nielsen, Stone and Edwards54 Another paternalistic approach described had patients earn privileges back slowly through participation in therapies. The concern with this technique is that this reinforces an external locus of control and downplays self-management strategies, further perpetuating reliance on the healthcare provider and system. Reference Nielsen, Stone and Edwards54 In reality, approaches that reinforce the passive and “faking” behaviors are a significant barrier to patients having access to appropriate treatment. Approaches to the management of functional symptoms need to ensure that trust and accountability underlie the care provider and patient relationship.

The studies included in this review suggest that inpatient intervention can have a positive impact on outcomes for those with functional symptoms. Inpatient populations add an additional challenge to understand the impact of each intervention, as multiple therapies are occurring simultaneously. Reference Nielsen, Stone and Edwards54 A multidisciplinary approach is often cited in the literature, but who is involved is dependent on available resources. The rationale for the selection of rehabilitation specialists was often not discussed.

The appropriate length of inpatient treatment remains unclear, but it can be inferred from this review that it is appropriate to admit patients with the goal of functional independence, but not total symptom resolution. When comparing symptom onset, patients presenting acutely had a mean length of stay of 2.9 days when compared to a mean of 27.8 days for those with symptoms occurring for greater than 3 months. This difference in length of stay likely reflects the differing goals of admission, with patients admitted acutely being discharged after the diagnosis is made rather than after deliberate aspects of treatment. Additionally, those with chronic symptoms had a mean onset of 5.8 ± 6.4 years compared to acute presentations of 5.2 ± 7.8 days. This has significant implications for healthcare utilization and cost. Future studies exploring a “staged approach” to functional symptoms, such as acute admission for motor symptoms followed by outpatient programs to support other comorbidities, such as depression, cognitive changes, pain, and fatigue, may be helpful in ensuring timely, appropriate diagnosis and treatment while reducing system burden.

The prognosis for patients with functional symptoms is often cited as poor in the literature, although previous studies likely underestimate recovery potential, as most patients do not receive treatment. Reference Lehn, Gelauff and Hoeritzauer55 Our review of inpatient treatment of functional symptoms is promising in terms of motor outcomes. Physiotherapy was consistently used as an inpatient intervention with positive results. The majority of patients return to independent function, but remain symptomatic after an inpatient stay, with the caveat that this review captures many patients described only in case reports and small case series. Patients admitted to psychiatric units were more likely to not improve or worsen compared to those admitted to acute care or rehabilitation wards, perhaps reflecting more complex psychiatric comorbidities and manifesting more severe disease; however, given the quality of the studies available, no recommendation can be made for an optimal inpatient setting to treat FND. Consistent use of validated tools is needed to better delineate outcomes based on settings, rehabilitation methods, and other interventions.

In terms of outcomes after discharge from hospital, most reported motor symptom recurrence occurred within a year after hospitalization with reported relapses occurring between 1 month and 2.5 years. For patients that did relapse, most recovered to functional independence with rehabilitation. All reported instances of symptom recurrence were described in patients with chronic symptoms (18% of chronic patients with reported follow-up); however, many acute presentation studies only followed patients for 1–3 months after discharge. Reference Richardson, Isbister and Nicholson34,Reference Trieschmann, Stolov and Montgomery37,Reference Teasell and Shapiro38,Reference Khalil, Abdel-Moty, Asfour, Fishbain, Rosomoff and Rosomoff40,Reference Moene, Hoogduin and Dyck44

The strengths of this review included the diverse terms for FND used and lack of constraints on date range, allowing for an extensive review of available literature. Furthermore, by not limiting publication date to a specific range, this review was able to capture a historical perspective and the shifting views of FND. Limitations of this review include restriction of language to English and French due to available translation resources, and the majority of the studies are case reports and case series, thus limiting the interpretation of the available data. In keeping with the intent of a scoping review, we did not formally address the quality of the included literature. The majority of patients in the included studies had motor symptoms, making conclusions difficult to apply to FND patients with non-motor symptoms. We believe that there may be a bias among clinicians to admit patients with motor symptoms, as these symptoms are often considered to be more amenable to standard neurorehabilitation programs. The duration of symptoms is likely often underestimated by patients and clinicians, with clinical experience revealing many patients often have functional symptoms, frequently non-neurological, occurring even in childhood. There is significant heterogeneity among inpatient therapy programs provided limiting any comparison between programs. Finally, it is a limitation to group together patients admitted electively with chronic symptoms and those admitted emergently with acute symptoms, as these patients are at very different points on their illness trajectory and, in some cases, may represent different FND populations. Attempts were made to separate these patients into distinct groups as part of this scoping review, but this was not always possible with the available data.

This scoping review summarizes the available literature on the inpatient treatment of both chronic and emergently admitted patients with FND in a variety of settings. With the current evidence, it remains unclear which patients benefit most from inpatient treatment of FND. This question may be a complicated one, with specific patient characteristics, such as primary motor symptoms and acute presentations, possibly leading to better outcomes in inpatient settings. This review identified that patients presenting with acute symptoms (<3 months) had better outcomes at discharge, without any reported relapses during the follow-up period. In contrast, patients presenting with longer duration of symptoms preceding admission had worse outcomes. Although not found in this review, possibly due to reporting bias, clinical experience indicates that patients with chronic symptoms may even decompensate in hospital. We postulate, based on the available inpatient data, that early diagnosis and inpatient rehabilitation in the acute phase could have a positive impact on outcomes for patients with FND.

There are several important areas within the field identified by this review that need to be addressed to ensure treatment is informed by high-quality data. Critically, there must be agreed-upon diagnostic criteria with standardized reporting, so that comparisons can be made between programs. In most countries, inpatient treatment is limited due to high cost and resource allocation. An important area of future research could be early, goal-directed therapy with the incorporation of standardized outcome tools, investigating specific patient characteristics preferentially responding to inpatient treatment that may guide the appropriate triaging of limited resources.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Gilmour has nothing to disclose. Ms. Jenkins has nothing to disclose.

Statement of authorship

GG: Conceptual idea for the article, literature search, data analysis, manuscript writing, and critical revisions. JJ: Conceptual idea for the article, literature search, data analysis, manuscript writing, and critical revisions. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.