Carotid stenosis is responsible for up to 20% of strokes in the adult population.Reference Linfante, Andreone, Akkawi and Wakhloo 1 Carotid artery stenting has been shown to be an effective and safe alternative to carotid endarterectomy, especially in patients at high risk for surgery.Reference Mas, Chatellier and Beyssen 2 , Reference Mantese, Timaran, Chiu, Begg and Brott 3

There is uncertainty about how stents actually remodel plaque and how they affect arterial diameters.Reference Benndorf, Ionescu, Alvarado, Hipp and Metcalfe 4 Although numerous studies have reported an improvement in flow and an increase in luminal diameter poststenting,Reference Lownie, Pelz, Lee, Men, Gulka and Kalapos 5 - Reference Coward, Featherstone and Brown 8 there is a lack of information about the relative effects of stent self-expansion on the plaque itself and the native arterial wall.

The purpose of this prospective study is to evaluate the relative effects of self-expanding nitinol stents on plaque remodeling and lumen and vessel diameter by analyzing pre- and postoperative carotid Doppler sonography (CDS) in stented patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

Between January 2006 and January 2008, 32 patients were selected from a prospectively maintained database of 136 patients for analysis based on the following criteria.

-

∙ Carotid artery stenting performed for either symptomatic carotid stenosis or high grade of asymptomatic (>70% based on North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial [NASCET] criteria) stenosis in the setting of a clinical trial. 9

-

∙ Pre- and postprocedural CDS available for the study.

-

∙ Patients with poor quality CDS images (vessel too deep for adequate insonation or extensive calcified plaque obscuring the lumen) were not included in the analysis.

Carotid Stenting Procedure

Patients were taking dual antiplatelet medication for at least 3 days before the intervention (either acetylsalicylic acid or clopidogrel); this was continued up to the time of the intervention. Clopidogrel was discontinued at 6 weeks of follow-up, whereas acetylsalicylic acid was continued indefinitely. The procedure was performed according to our previously published protocol.Reference Lownie, Pelz, Lee, Men, Gulka and Kalapos 5 The stenosis was crossed with an 8-mm-diameter x 40-mm-length self-expanding stent, either with Acculink (Abbott) in 20% of cases, or Precise stent (Cordis) in 80% of cases. According to our previous experience,Reference Lownie, Pelz, Lee, Men, Gulka and Kalapos 5 balloon assistance was used only when necessary to initially cross a severe stenosis with the stent, or if a significant stenosis remained after deployment of the stent, usually resulting from a circumferential plaque calcification. Distal protection devices can add risk to the procedureReference Cremonesi, Manetti, Setacci, Setacci and Castriota 10 and are not included in our routine treatment protocol. Following stent deployment, angiographic views of the neck and head were obtained. The heparinization was allowed to gradually wear off.

Radiological Assessment

The degree of stenosis before stent deployment was quantitated using the NASCET criteria. 9 Follow-up assessment was done with periodic CDS. These studies were carried out within 1 week of the procedure, then once or twice in the next 6 months, once again during the next 12 months, and every 6 months or annually thereafter. The effect on carotid remodeling was assessed by comparing the preprocedural results and the last follow-up results available.

CDS Measurements

All measurements were assessed by a neuroradiologist not involved in the stent deployment (DHL). For better evaluation of the remodeling effects of internal carotid artery (ICA) stenting, the CDS examinations were performed using the same machine. A two-dimensional ultrasound system, equipped with a 10-MHz scanning frequency in real-time B-mode and 6 MHz scanning frequency in pulsed Doppler mode, was used. The examination included the longitudinal view of the affected extra cranial carotid artery. These were chosen rather than transverse planes to better assess the region of plaque. Total vessel diameter and ventral plaque and dorsal plaque thickness were assessed using the real-time B-mode at the most stenotic site (Figure 1). The middle, proximal, and distal diameters were assessed using the color-coded flow imaging in the Doppler mode (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Follow-up representative B-mode ultrasound from patient 11 in our series detailing the measurements obtained for statistical analysis. The stent (white arrows) is visualized as a hyperecogenous signal in the periphery of the vessel. The proximal (p) and distal diameter (d) of the vessel is measured at 1 cm from the plaque edge, as shown in the image (*) in millimeters. The ventral (v) and dorsal (d) plaque thickness and mid-vessel diameter (+) are measured in millimeters at the midpoint of the plaque (arrowhead).

Figure 2 Color Doppler image of the same patient, which was used to obtain the luminal diameter. Three-dimensional color Doppler ultrasound, sagittal view. Red=blood flow. *Luminal diameter measured in millimeters at the most stenosed segment.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0. Testing was done using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student t test distribution for paired samples. A two-tailed p value<.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Thirty-two patients were initially included in the study. After reviewing the ultrasound images, two patients were excluded for having heavy calcified plaques. Of the 30 individuals studied, 18 men and 12 women with an average age of 70 years (range, 54-91) were included. Thirteen percent of the patients were asymptomatic and 87% had symptoms related to the site of the stenosis. Symptoms included 17 patients with transient ischemic attacks, eight with stroke, and one with amaurosis fugax. Five patients had moderate stenosis; the remainder had severe stenosis. Mean of degree of stenosis, according to NASCET criteria, 9 was 77.2% preprocedure and 39.7% after the main procedure.

Nine patients had intraprocedural angioplasty; two had prestent angioplasty and seven had angioplasty poststent stent deployment. No protective devices were used in any patient. Pairwise comparison testing did not show significant differences in terms of lumen diameter, vessel diameter, or plaque thickness between those patients additionally treated with angioplasty and those who received the self-expandable stent without pre- or postangioplasty (p>0.05).

None of the patients who received the self-expandable stent without additional angioplasty experienced any direct complication derived from the procedure or new neurological deficits. One of the patients treated with postprocedural angioplasty had an auto-limited episode of 20 minutes of amaurosis fugax. It was managed conservatively and the patient recovered to his baseline state.

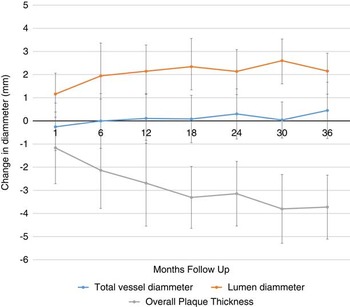

Paired results of pre- and postprocedure angiography were available in all 30 patients. Average follow-up was 22 months (range, 1-50 months). Eight patients had less than 1-year of follow-up. Changes in vessel diameter, lumen diameter, and plaque thickness during the follow up are represented in Figure 3.

Figure 3 CDS measurements along the study follow-up.

The changes in CDS parameters between the prestent studies and last follow-up are listed in Table 1. Significant differences poststenting occurred for the plaque morphology (either ventral or dorsal) and luminal measurements, but not for the proximal, mid, or distal outer arterial vessel diameter.

Table 1 Mean difference±SD for each of the 6 measured values between the baseline (i.e. pretreatment) and final poststent ultrasound

p values demonstrate the results of paired t test and repeated measures ANOVA analysis of the baseline and final poststent measurements.

Pairwise comparison testing indicates no difference in stent expansion in terms of its effect on the ventral and dorsal plaque (i.e. they each remodel to an equal degree; p>0.05).

DISCUSSION

Carotid stents can expand for up to 6 months after the procedure.Reference Lownie, Pelz, Lee, Men, Gulka and Kalapos 5 , Reference Willfort-Ehringer, Ahmadi and Gruber 6 , Reference Clark, Lessio, O’Donoghue, Tsalamandris, Schainfeld and Rosenfield 11 . This finding is confirmed in the present study, showing an average diameter increase of more than 2 mm over an average follow-up of 22 months. However, little is known about the relative effect of the stent on plaque thickness compared with overall expansion of the external arterial wall. In vitro experimental studies based on the use of rigid polytetrafluoroethylene stents have suggested that stents affect plaques symmetrically because of radial effects,Reference Benndorf, Ionescu, Alvarado, Hipp and Metcalfe 4 , Reference Mohr, Wenke and Roemer 12 but this finding has not yet been shown in humans.

Our major findings were as follows: (1) self-expanding nitinol stents alter the baseline ventral and dorsal plaque thickness to a significant degree, while not significantly affecting the native arterial wall; and (2) stenting appears to impact the ventral and dorsal components of the plaque equally, which would be expected given their radial expansion.Reference Voute, Hendriks and van Laanen 13 , Reference Ghriallais and Bruzzi 14

Our results suggest that an increase in luminal diameter is achieved by a process of plaque remodeling and is not accompanied by native arterial expansion. The radial outward force produced by a self-expanding stent compresses the plaque component in all directions in a similar manner, but this force is not enough to produce a dilatation of the arterial wall, avoiding the risk of vessel rupture. No previous investigators have looked at changes in outer vessel wall diameter, although there have been reports of vessel wall rupture with subsequent hematoma and pseudo aneurysm formation.Reference Stirling, Smith and McCann 15 , Reference Broadbent, Moran, Cross and Derdeyn 16 It is unclear whether these complications were due to balloon expansion, by the stent, or by a combination of both. It is well-known that artery wall disruption and other complications are much more common in angioplasty with angioplasty balloons and balloon expandable stents than with self-expanding stents alone.Reference Rosenkranz, Eckert, Niesen, Weiller and Sliwka 17 , Reference Dieter, Ikram, Satler, Babrowicz, Reddy and Laird 18 This is a potential benefit of self-expanding stents over balloon-expandable stents. Self-expanding stents gradually reduce the stenosis over time, without inducing changes in the external arterial wall, reducing rupture risk. There is good evidence that arterial injury with both balloons and stents leads to an inflammatory response and activates a proliferative repair process, the end result of which can lead to luminal narrowing and in-stent restenosis.Reference Willfort-Ehringer, Ahmadi and Gruber 6 , Reference Clark, Lessio, O’Donoghue, Tsalamandris, Schainfeld and Rosenfield 11 , Reference Farb, John, Acampado, Kolodgie, Prescott and Virmani 19 , Reference Barth 20 These results could not be confirmed in our study, but this could be influenced by small size of the sample. Avoidance or limitation of arterial injury associated with balloon inflation may also be beneficial in minimizing such restenosis.Reference Rosenkranz, Eckert, Niesen, Weiller and Sliwka 17 , Reference von Birgelen, Kutryk and Serruys 21 It is believed that balloon distention of the carotid sinus is responsible for hemodynamic depression intra- or postoperatively.Reference Qazi, Obeid and Enwerem 22 , Reference Leisch, Kerschner and Hofmann 23 The use of self-expanding stents alone can minimize this risk.Reference Bussiere, Pelz and Kalapos 24

The acceptable reproducibility and interobserver reliability of the measurements of the plaque thickness and lumen diameter has been previously reported.Reference Willfort-Ehringer, Ahmadi and Gruber 6

Limitations of this study include metallic artifact produced by the stent, which can underestimate the real value of the lumen diameter on CDS.

Several papersReference Willfort-Ehringer, Ahmadi and Gruber 6 , Reference Clark, Lessio, O’Donoghue, Tsalamandris, Schainfeld and Rosenfield 11 have remarked that neointimal proliferation prevails at an early stage, up to 12 months, which corresponds to the period of maximal stent expansion. Rarely, this can result in early restenosis. Later on, the neointimal proliferation remains stable and positive remodeling gains prominence. In our series, 26% of patients examined were followed for less than 1 year, and the degree of intimal remodeling may be underestimated.

Use of CDS has some limitations. Plaque with dense calcification, a carotid bifurcation with marked tortuosity, and a high cervical stenosis may not be adequately imaged. 9 Two of our patients had to be excluded from the study for having heavy calcified plaques.

Our two-dimensional carotid Doppler date demonstrates changes in ventral and dorsal plaque thickness, without significant differences in thickness between dorsal and ventral. A three-dimensional radiological diagnostic method, such a high-resolution computed tomography scan would confirm whether this changes truly occur equally in all the plaque in vivo, particularly in areas of heavy calcification.

CONCLUSIONS

The plaque is remodeled by the outward radial force produced by the self-expandable stents, without producing changes in diameter by expanding the external carotid wall, Stenting appears to impact the ventral and dorsal components of the plaque equally, which would be expected given their proposed method of radial expansion.

Acknowledgments and Funding

The authors have no source of funding relative to the research or elaboration of this work.

Disclosures

RPM has received research support from the Fundacion Alfonso Martin Escudero, Madrid, Spain, for his fellowship at Western University. The remaining authors do not have any disclosures.