Choreoballism (CB) can develop as a complication of diabetes mellitus (DM). Although the recurrence of CB was reported, it was related to drug discontinuation or transient hyperglycaemia or was without evident provoking factors.Reference Oh, Lee, Im and Lee 1 Herein, we report a case of hyperglycaemic CB that persisted for longer than a year, was resolved by cerebral infarction, and then returned after medical illness.

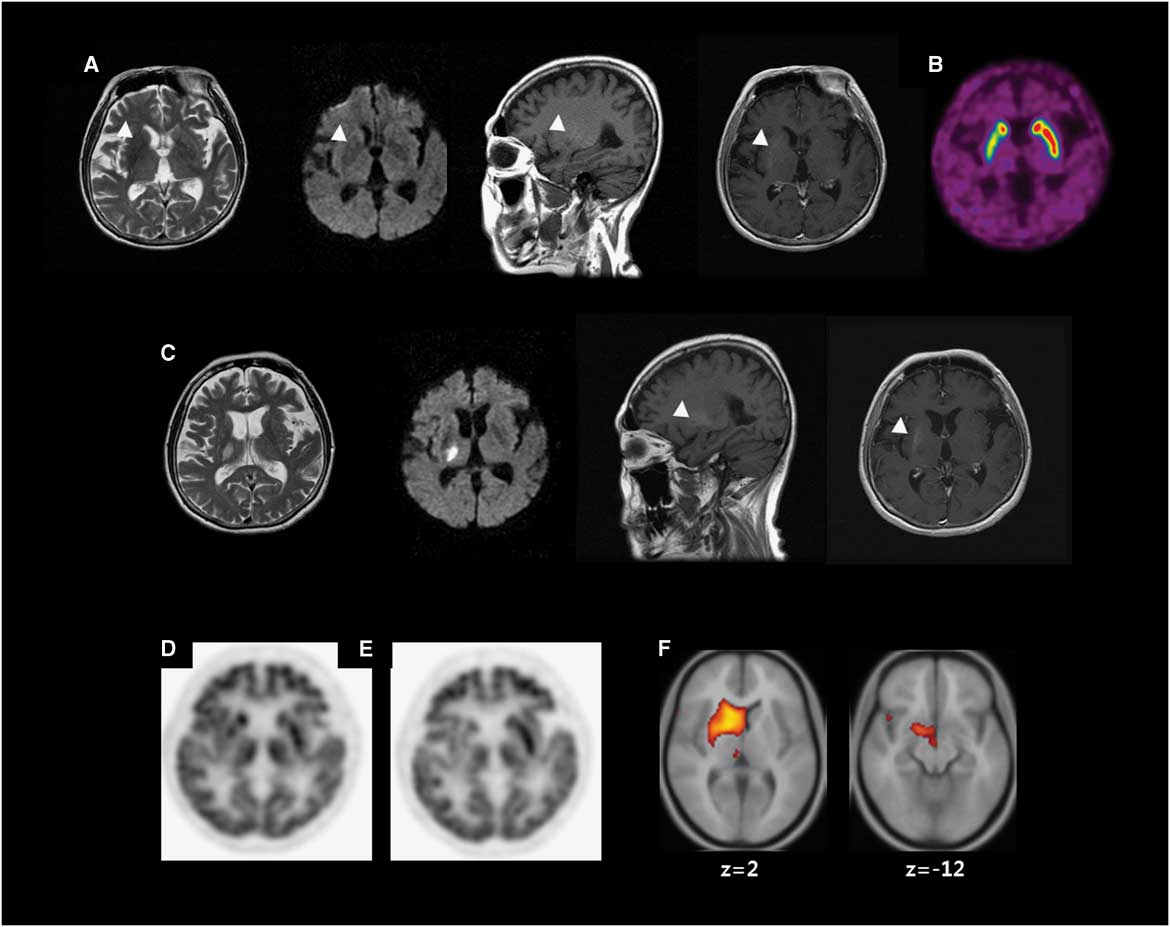

A 62-year-old woman with poorly controlled DM visited our department due to sudden-onset involuntary movements. Her neurological examination (NE) was normal, with the exception of involuntary movements consisting of continuous, irregular, mixed choreic and ballistic movements involving the left face, arm and leg. At admission, her serum glucose was 195 mg/dl and her glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) 16.2%. MRI showed hypointensities on T2-weighted image, hyperintensities on T1-weighted image and normal diffusion-weighted image in the right putamen (Figure 1A). 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG–PET) showed hypometabolism in the right putamen (Figure 1D).

Figure 1 Neuroimaging. (A) Brain MRI at the first presentation of hemichorea shows low signal intensity on T2-weighted image (T2WI), high signal intensity (HSI) on T1-weighted image (T1WI) without (sagittal) or with (axial) gadolinium enhancement and diffusion weighted image (DWI) (arrow heads). (B) 18F-fluorinated N-3-fluoropropyl-2-beta-carboxymethoxy-3-beta-(4-iodophenyl) nortropane (18F-FPCIT) positron emission tomography (PET) shows decreased 18F-FPCIT uptake in the right putamen. (C) The third MRI shows acute infarction in the right thalamus on T2WI and DWI. T1WI without (sagittal) or with (axial) gadolinium enhancement shows persistent HSI in the right putamen (arrow heads). (D) 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET shows hypometabolism in the right putamen. (E) A follow-up 18F-FDG–PET shows hypometabolism in the right caudate nucleus (CN), putamen and thalamus (54 months after the initial 18F-FDG–PET). (F) Voxel-based subtraction analysis of 18F-FDG–PET shows decreased metabolism of the right CN, putamen, subthalamic area and thalamus in the follow-up scan.

Serum glucose was controlled (HbA1c<7 %). Various drugs including haloperidol and tetrabenazine were ineffective for CB. She showed postural instability after anti-dopaminergic drugs including clozapine. The second MRI showed no new lesions. 18F-fluorinated N-3-fluoropropyl-2-beta-carboxymethoxy-3-beta-(4-iodophenyl) nortropane (18F-FPCIT) PET showed decreased uptake in the right putamen (Figure 1B). Levodopa was effective. Both clozapine and levodopa were tapered, leaving CB as the lone symptom.

She had been followed up for persistent CB for 15 months until sudden-onset left hemiparesis developed. The third MRI showed an acute infarction in the right thalamus (Th) and corona radiata (CR; Figure 1C). NE showed left hemiparesis without sensory deficit. After she recovered from hemiparesis, she remained free of CB.

Three years later, she was hospitalized for coronary heart disease and an appendectomy (HbA1c<7.5%). The hemichorea returned during hospitalization without any suspected drugs. Choreic movements of her left hand were temporarily mixed with dystonia in the early follow-up but became purely choreic later. No new lesion was demonstrated on the fourth MRI. 18F-FDG–PET was repeated and compared with the previous using voxel-based subtraction analysis, demonstrating decreased metabolism in the right subthalamic nucleus (STN), caudate nucleus (CN), putamen and Th (Figure 1E–F).

Because of multiple morbidities and mildly severe hemichorea, only clonazepam was added. Her hemichorea persisted for longer than a year.

The patient’s CB was present for 15 months before an infarction and persisted after recurrence. The protracted clinical course was not related to DM control. Delayed introduction of DRB and an extended lesion were suggested as risk factors for persistent CB, but were not applicable to our case.Reference Su, Chang, Liu, Lan and Liu 2

Because dystonic movement was mixed with chorea in the early phase of the recurrence, post-stroke dystonia or pseudoathetosis related to the thalamic infarction is to be considered. Interestingly, the involuntary movements became purely choreic afterwards. The phenotypic transition could be a result of repositioning the role of Th upon recurrence.

A few cases with essential tremor have been reduced by structural lesions interrupting the corticospinal tract or cerebellar connection.Reference Hallett 3 One case of hyperglycaemic CB resolved due to an infarction that affected the CR and putamen.Reference Kim, Cho, Song and Chung 4 In the present case, the infarction affected the CR and Th, a key BG loop structure that activates the cortex. The thalamic lesion hampered activation of the cerebral cortex, which played a critical role in terminating her CB in addition to CR infarction.

PET subtraction analysis revealed hypometabolism in the CN and STN. Focal lesions in either the CN or STN have been shown to result in secondary CB. Thus, the recurrence of her hemichorea could be related to STN or CN dysfunction, which could dominate over the beneficial effect of pre-existing Th infarction on her CB. Previously, we suggested that a faulty network for CB had formed during the first episode as a pathologic basis for recurrence in a patient with hypoglycaemic CB.Reference Lee, Lee, Ahn, Hong and Kim 5 Similarly, an aberrant network could have been generated during the initial episode under the influence of the putaminal lesion. This network might have been further modified by an additional thalamic lesion, which was evidenced by a temporary combination of chorea and dystonia. Although the direct mechanism of hypometabolism in the CN and STN was uncertain, this network might consist of structural lesions in the putamen and thalamus and metabolic derangement of the CN and STN. The pathologic network might have been submerged, until it may be relinquished in association with multiple factors such as unstable circulation and surgery.Reference Lee, Lee, Ahn, Hong and Kim 5 The relationship between this hypothetical network and the prolongation of CB remains to be studied.

An abnormal dopamine transporter scan was once reported in a patient without parkinsonism.Reference Belcastro, Pierguidi, Tambasco, Sironi, Sacco and Corso 6 In this case, as 18F-FPCIT–PET was normal in the left putamen, her postural instability recovered, and no other parkinsonian symptoms and signs were observed during follow-up, and she was not suffering from ongoing de novo parkinsonism. However, striatal dopamine deficiency might be a risk factor for her vulnerability to clozapine.

This case captures uncommon features of hyperglycaemic CB, such as repeated prolongation of clinical course and recurrence. To our knowledge, this is the first case of CB resolution by Th infarction. In addition, recurrence related to STN and CN hypometabolism is also unprecedented, providing insight into CB pathophysiology.

Disclosures

The authors hereby declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2016.265