1. Introduction

Noun classifiers (distinct from more familiar numeral classifiers) are a typologically rare class of grammatical item attested in only a limited set of language families, including the Q'anjob’alan branch of Mayan languages (Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald2000, Grinevald Reference Grinevald and Senft2000). Though Q'anjob’alan noun classifiers have received considerable attention in the Mayanist literature (see, e.g., Craig Reference Craig1986 on Popti’; Buenrostro et al. Reference Buenrostro, Díaz and Zavala1989 and Royer Reference Royer, Nee, Cychosz, Hayes, Lau and Remirez2017 on Chuj; Zavala Reference Zavala and Senft2000 on Akatek; Mateo Toledo Reference Mateo Toledo, Aissen, England and Maldonado2017 on Q'anjob’al; and Hopkins Reference Hopkins2012b on the Q'anjob’alan languages more generally), they have received little study in formal semantics. This article aims to fill this gap, by taking a close look at the distribution of noun classifiers in one Q'anjob’alan language: Chuj. In particular, I show that the distribution of noun classifiers can inform us on the underlying syntax and semantics of the distinction between weak and strong definites (Schwarz Reference Schwarz2009, Reference Schwarz2013, Reference Schwarz, Aguilar-Guevara, Loyo and Maldonado2019), and how this distinction connects to pronouns, if pronouns are to also be understood as definite descriptions (Postal Reference Postal1966, Evans Reference Evans1977, Cooper Reference Cooper, Henry and Schnelle1979, Déchaine and Wiltschko Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002, Elbourne Reference Elbourne2005).

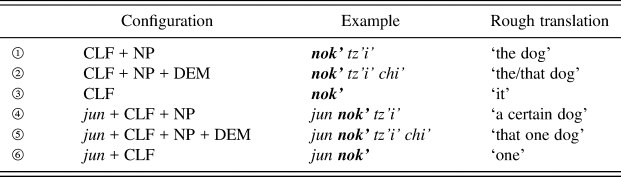

Chuj is spoken by about 70,000 speakers in Guatemala and Mexico (Piedrasanta Reference Piedrasanta2009, Buenrostro Reference Buenrostro2013). In the variant under study, there are 16 noun classifiers, described in more detail below, which classify nouns according to physical and social attributes (Maxwell Reference Maxwell1981, Buenrostro et al. Reference Buenrostro, Díaz and Zavala1989). Chuj's noun classifiers exhibit a wide distribution, appearing in a variety of syntactic and semantic environments, and playing what appears to be a central role in the composition of DP. Table 1 summarizes the syntactic environments in which they appear.Footnote 1

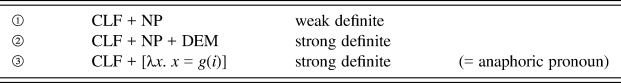

In this article, I focus on the configurations in ①-③ of Table 1: when classifiers appear alone with nouns, when they co-occur with a demonstrative, and when they appear alone as pronouns. Building on observations in previous work (Buenrostro et al. Reference Buenrostro, Díaz and Zavala1989, García Pablo and Domingo Pascual Reference García Pablo and Pascual2007), I argue that noun classifiers are best analyzed as weak definite determiners in the sense of Schwarz Reference Schwarz2009: they contribute a uniqueness presupposition. I further argue that the distribution of Chuj noun classifiers offers important insight into the growing literature that establishes a distinction between weak and strong definites (Schwarz Reference Schwarz2009, Aguilar-Guevara et al. Reference Aguilar-Guevara, Loyo and Maldonado2019). As we will see, this distinction in Chuj is clearly achieved compositionally, rather than being lexically encoded in separate determiners, as proposed in Schwarz Reference Schwarz2009, Arkoh and Matthewson Reference Arkoh and Matthewson2013, and Jenks Reference Jenks2018.

In a nutshell, I will argue that noun classifiers occur in the configurations in ①-③ of Table 1 because these configurations all involve a uniqueness presupposition, contributed by noun classifiers, which I analyze as weak definite determiners. This accounts for the use of noun classifiers alone with nouns ①. To create strong definites, which further contribute an anaphoricity (or familiarity) presupposition (Schwarz Reference Schwarz2009), noun classifiers must combine with additional morphology. In particular, the anaphoricity presupposition, formalized with an index interpreted relative to a contextually-determined assignment function, is triggered by demonstratives ②.

Table 1: Possible DP configurations with noun classifiers

Finally, if noun classifiers are uniformly weak definite determiners, a question arises as to why they can be used alone as pronouns ③, which in most cases are used anaphorically. I argue that anaphoric third person classifier pronouns in Chuj are essentially E-type pronouns (Cooper Reference Cooper, Henry and Schnelle1979, Heim Reference Heim1990): weak definite classifiers that combine with a covert index-introducing predicate. As such, classifier pronouns are just an alternative form of strong definite, with the anaphoricity presupposition being introduced covertly.Footnote 2 The proposed semantic outputs for each of the configurations in ①-③ are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Classifier configurations and semantic output

This article focuses only on the configurations in rows ①-③ of Table 1. The presence of noun classifiers in rows ④-⑥, where the classifier co-occurs with the indefinite jun, also the numeral ‘one’ in Chuj (García Pablo and Domingo Pascual Reference García Pablo and Pascual2007), may at first glance seem incompatible with the proposal that classifiers are weak definite determiners. However, in other work (Royer Reference Royer, Baird and Pestesky2019) I argue that when combined with an indefinite determiner, noun classifiers force specific interpretations of indefinites, and that these observations can be captured by maintaining an analysis of classifiers as weak definite determiners. I argue that in such cases classifiers introduce a covert NP, with the DP headed by the classifier type-shifting to restrict the domain of the indefinite determiner DP to a singleton set, creating a singleton indefinite (Schwarzschild Reference Schwarzschild2002). In the rest of this paper, I set aside the data in ④-⑥, and assume that even in their co-occurrence with jun, noun classifiers could be analyzed as morphemes that presuppose uniqueness.

In section 2, I provide information on Chuj and briefly discuss previous analyses of noun classifiers in Q'anjob’alan languages. In section 3, I summarize the discussion of weak and strong definite determiners in Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009) and argue that Chuj noun classifiers are weak definites. In section 4, I argue that strong definites are built compositionally in Chuj, and provide a formal analysis of this composition. In section 5, I account for pronominal uses of noun classifiers.

2. Chuj noun classifiers

Like most Mayan languages, Chuj exhibits basic verb-initial word order, though SVO is also common since DPs appear preverbally when topicalized or focused (see England Reference England1991, Aissen Reference Aissen1992, and Clemens and Coon Reference Clemens and Coon2018 on Mayan word order). Chuj is a head-marking language and there is no case morphology on nominals.Footnote 3

A notable aspect of Q'anjob’alan languages is their extensive system of nominal classification, described at length in Day (Reference Day1973); Craig (Reference Craig1977, Reference Craig1986); Zavala (Reference Zavala1992, Reference Zavala and Senft2000); and Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2012b). As an example, consider the morphemes that classify the noun ajb'ulej ‘person from B'ulej’ in the following naturally-occurring utterance:

In (1), a total of three morphemes covary based on the properties of the noun ajb'ulej. First, -wanh is a numeral classifier signalling that the noun is animate. Second, heb’ is a plural marker that appears only with human-denoting nominals. Finally, the noun classifier winh indicates that the noun is male.

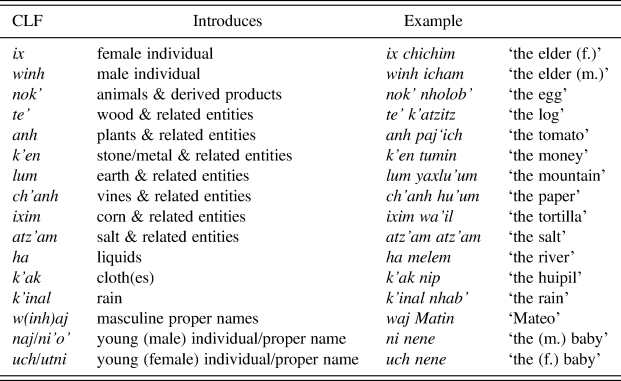

Crucially, noun classifiers and numeral classifiers are distinct morphemes, evidenced by the fact that they may sometimes co-occur, as in (1). Here we focus only on the syntactic and semantic distribution of noun classifiers, provided in Table 3 (see Hopkins Reference Hopkins1970, Reference Hopkins2012a on numeral classifiers in Chuj).

Table 3: Chuj noun classifiers (see also Hopkins Reference Hopkins2012b)

Note that all noun classifiers closely resemble a noun in the language, a fact that Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2012b) attributes to the recent development of the noun classifier system. For instance, ix, the classifier for female entities, is homophonous with the noun ix ‘woman’, and nok’, the classifier for animals, is homophonous with nok’ ‘animal’.

The wide distribution of noun classifiers, highlighted in Table 1, has led previous researchers to offer more general accounts of their distribution. Craig (Reference Craig1986) and Zavala (Reference Zavala and Senft2000), working on Popti’ and Akatek (both closely-related to Chuj), argue that noun classifiers are related to notions of “referentiality”, such as the marking of “pragmatically important participants in discourse”. These accounts, however, are either not sufficiently defined such that they make clear predictions – for example, “referential” is left undefined – or make wrong predictions.Footnote 5 To illustrate how these accounts make wrong predictions, consider the following narrative sequence:

An account that treats noun classifiers as markers of important participants in discourse predicts that their presence should sometimes, if not always, be optional. In the narrative sequence in (2), the speaker is telling the addressee that Xun, a man that they know, was lying unconscious on the floor. The noun pwerta ‘door’ is not an important participant in this conversation, yet the presence of a classifier is enforced.

In the rest of this article, I depart from these more general accounts. In particular, I propose that noun classifiers instantiate weak definite determiners, in the sense of Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009, Reference Schwarz2013). For Reference SchwarzSchwarz, weak definites are “Fregean” (Frege Reference Frege, Geach and Black1892), in that they encode a presupposition that there is a unique satisfier of the predicate that they take as an argument (see also Strawson Reference Strawson1950; Heim Reference Heim, von Stechow and Wunderlich1991; Elbourne Reference Elbourne2005, Reference Elbourne2013). Following Percus (Reference Percus2000), Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009, Reference Schwarz2012), and Elbourne (Reference Elbourne2013), I further assume that determiners involve a syntactically represented but unpronounced situation pronoun (Barwise and Perry Reference Barwise and Perry1983; Kratzer Reference Kratzer1989, Reference Kratzer2019), which in part serves to restrict the domain of the determiner. The proposed denotation for noun classifiers is provided in (3).Footnote 6 As suggested for the weak definite determiner in Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009), I propose that the noun classifier takes two arguments, a situation pronoun and an NP predicate, and returns the unique satisfier of that NP in the situation. If there is no unique satisfier of the NP in the situation, the uniqueness presupposition in (3) is not met and the output is undefined.

(3) Denotation of noun classifiers (= weak definite determiner)Footnote 7

⟦ CLF ⟧ = λs.λP 〈e,〈s,t〉〉:

$\exists$!x[P(x)(s)].

$\exists$!x[P(x)(s)]. $\iota$x[P(x)(s)]

$\iota$x[P(x)(s)]

3. Chuj classifiers as weak definite determiners

After providing background on the distinction between weak and strong definites, this section provides evidence that noun classifiers are weak definite determiners. I then argue in section 4 that strong definites are derived compositionally in Chuj, by combining weak definite classifiers with additional morphology. Section 5 then accounts for pronominal uses of noun classifiers

3.1 Background: Two kinds of definites across languages

Though there are many approaches to the semantics of definiteness, two families of accounts stand out. On the one hand, some accounts posit that definite determiners introduce a uniqueness (or maximality) presupposition (e.g., Frege Reference Frege, Geach and Black1892; Russell Reference Russell1905; Strawson Reference Strawson1950; Hawkins Reference Hawkins1978; Heim Reference Heim, von Stechow and Wunderlich1991; Heim and Kratzer Reference Heim and Kratzer1998; Elbourne Reference Elbourne2005, Reference Elbourne2013; Coppock and Beaver Reference Coppock and Beaver2015). On the other hand, some accounts posit that definite determiners encode a presupposition that the speaker and addressee are familiar with the referent of the DP (Christophersen Reference Christophersen1939, Kamp Reference Kamp, Groenendijk, Janssen and Stokhof1981, Heim Reference Heim1982, Chierchia Reference Chierchia1995). There are also hybrid accounts, which incorporate aspects of both views (e.g., Farkas Reference Farkas2002, Roberts Reference Roberts2003).Footnote 8

More recently, based on observations in Ebert Reference Ebert and Wunderlich1971 that some languages overtly distinguish between different kinds of definite articles, Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009) proposes that there are two kinds of definite determiners crosslinguistically: weak definites, which encode only uniqueness, and strong definites, which encode both uniqueness and anaphoricity. The overt contrast between weak and strong definites is observed in German in the ability of different article forms to contract with prepositions. Weak definite forms of articles occur in environments where the referent of the DP is unique in the context, but where it has been neither previously mentioned in discourse nor deictically identified. Example (4) illustrates this, with the key feature to notice being that the weak article phonologically contracts with the preposition von:

(4) Weak definite article in German

Der Empfang wurde vom /#von dem Bürgermeister eröffnet.

the reception was by.theweak /by thestrong mayor open

‘The reception was opened by the mayor.’ (Schwarz Reference Schwarz2009: 42)

Strong definites, on the other hand, are required when the referent of the DP is present in prior discourse as well as when the referent is deictically identified. In that case, contraction with the preposition is not possible, as illustrated in (5):

As Reference SchwarzSchwarz shows, the above two examples are only a subset of environments in which weak and strong definites are observed. In sections 3.2 and 4, I discuss a broader range of environments in which both kinds of definites arise. As we will see, Chuj consistently marks the distinction characterized by Reference SchwarzSchwarz.

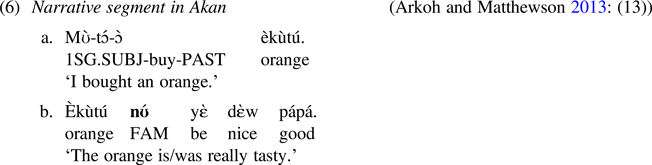

While the weak/strong definite contrast in German is only perceivable when a determiner appears adjacent to a preposition, we will see that it is perceivable throughout all definite environments in Chuj. This is also the case in other languages that have been reported to exhibit a contrast between weak and strong definites. For instance, Arkoh and Matthewson (Reference Arkoh and Matthewson2013) argue that while weak definites are realized as bare nouns in Akan (Kwa, Niger-Congo), strong definites require the ‘familiar’ determiner nʊ́. An example illustrating this use of nʊ́ is provided in (6).

In (6b), the referent of èkùtú ‘orange’ has already been introduced in the previous sentence (6a), and is therefore familiar. The use of nʊ́ in (6b) is enforced.

Akan weak definites, on the other hand, do not tolerate the presence of nʊ́. According to Arkoh and Matthewson (Reference Arkoh and Matthewson2013), the sentence in (7) is odd given the context they provide, because the referent of bànkyí is not familiar to the hearer.

In recent work, Jenks (Reference Jenks2018) highlights similar facts in Mandarin: while weak definites are realized as bare nouns in this language, strong definites obligatorily appear with a demonstrative. As we will see, this is even more similar to Chuj, which also requires the use of demonstratives with strong definites. For example, consider the following narrative segment, adapted from Jenks (Reference Jenks2018):

As shown above, definites that have been previously introduced in discourse in Mandarin require the presence of a demonstrative. This is contrary to weak definites, which according to Reference JenksJenks, must surface as bare nouns (see, for instance, the absence of a demonstrative with the noun jiaoshi ‘classroom’).

Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009), Arkoh and Matthewson (Reference Arkoh and Matthewson2013) and Jenks (Reference Jenks2018) all provide an account of the weak/strong definite distinction by assuming that they are separate lexical items. In particular, they argue that strong definites have the same core semantics as weak definites, with the minimal addition that strong definites take an extra index-introducing argument. The denotations for weak and strong definite determiners, modelled in situation semantics (Barwise and Perry Reference Barwise and Perry1983, Kratzer Reference Kratzer1989), are reproduced below from Schwarz Reference Schwarz2009:

In the above denotations, both the weak definite (9a) and the strong definite (9b) presuppose uniqueness within a particular situation. The crucial difference lies in the fact that the strong definite takes an extra index argument (λy), which has the effect of introducing an anaphoricity (or familiarity) condition.Footnote 9 Assuming that the index argument is saturated by a covert variable, whose value will be determined by the assignment function, the denotation of strong definites will only be defined if the satisfier of the NP argument is also in the range of the assignment function, and thus anaphorically or deictically identifiable to the speaker and hearer.

Importantly, Reference Arkoh and MatthewsonArkoh and Matthewson and Reference JenksJenks share the assumption in Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009) that the distinction between weak and strong definites is realized by separate lexical items. While weak definites are derived via a covert determiner in Akan and Mandarin (as in, e.g., Chierchia Reference Chierchia1998), strong definites independently encode both a uniqueness and anaphoricity presupposition.

In addition to Arkoh and Matthewson (Reference Arkoh and Matthewson2013) and Jenks (Reference Jenks2018) on Akan and Mandarin, Reference SchwarzSchwarz's (Reference Schwarz2009) observations on the crosslinguistic nature of definiteness have led to a large body of work, with a great deal of evidence that languages across various families distinguish weak and strong definites (e.g., Jenks Reference Jenks, D'Antonio, Moroney and Little2015 on Thai, Cho Reference Cho2016 on Korean, Ingason Reference Ingason2016 on Icelandic, Simpson Reference Simpson2017 on the Jinyun variety of Chinese, Cisnero Reference Cisnero, Aguilar-Guevara, Loyo and Maldonado2019 on Cuevas Mixtec, Irani Reference Irani, Aguilar-Guevara, Loyo and Maldonado2019 on American Sign Language, Schwarz Reference Schwarz, Aguilar-Guevara, Loyo and Maldonado2019 on various languages, Šereikaitė Reference Šereikaitė, Aguilar-Guevara, Loyo and Maldonado2019 on Lithuanian, and Little Reference Little2020 on Ch'ol). In the following sections, I contribute to this view of definiteness with additional empirical support from Chuj, showing that it also overtly marks this distinction. However, I show that Chuj strong definites are transparently decomposed with a weak definite, namely the classifier, as their core. As such, Chuj shows overt evidence that strong definites can be derived compositionally, contrasting with the theories developed in Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009), Arkoh and Matthewson (Reference Arkoh and Matthewson2013) and Jenks (Reference Jenks2018), where weak and strong definites are hardwired as separate lexical items. In providing a decompositional account, my proposal aligns with a recent proposal by Hanink (Reference Hanink2018, Reference Hanink2020), who also provides a decompositional account of this distinction in German and Washo. I will, however, argue for a different compositional route to strong definiteness. This will have important consequences for the resulting interpretation, namely whether the uniqueness presupposition of strong definites is evaluated relative to the intersection of the NP predicate with the index argument, as in Hanink Reference Hanink2018 and other work, or only with respect to the NP predicate itself. In arguing for the latter option, the current proposal ultimately suggests that there may be variation in the interpretive properties of strong definites across languages.

3.2 Weak definites in Chuj

Based on crosslinguistic evidence, Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009, Reference Schwarz2013, Reference Schwarz, Aguilar-Guevara, Loyo and Maldonado2019) argues that the different uses of definite determiners in (10) all involve “weak definites”. As we will see below, all of these subtypes of definites in Chuj are realized by combining a classifier with a noun, suggesting that noun classifiers pattern like weak definite articles.Footnote 10

(10) Subtypes of weak definites

1. “Immediate” situation uses of definites

2. “Larger/global” situation uses of definites

3. Kind-denoting definites

4. Situation-dependent covarying uses of definites

The terms “immediate” and “larger situation uses” are due to Hawkins (Reference Hawkins1978), who argues for a uniqueness-based approach to definite determiners. Briefly, immediate-situation uses occur when a speaker makes reference to a unique entity present in the immediate context (e.g., the table, if the speaker is in a kitchen). Larger situation uses, on the other hand, occur when a speaker makes reference to a unique entity in a larger context (e.g., the president, if the speaker is in Guatemala and is referring to the current president of Guatemala).

In Chuj, both immediate and larger situation uses of definite articles require the presence of a noun classifier, as expected if classifiers are weak definites. Examples of immediate and larger situation uses are provided in (11) and (12):

Importantly, if there is no unique satisfier of the NP predicate in (11) and (12), a classifier–noun construction cannot be used. Consider, for instance, (13):

The third use identified in (10) is the use of definite articles to refer to kinds, a relatively common pattern across languages (see, e.g., Chierchia Reference Chierchia1998). As illustrated in (14), Chuj classifiers are required in such cases:

In the above example, nok’ ajawchan ‘the rattlesnake’ does not refer to a particular rattlesnake, but to rattlesnakes in general. Again, the necessity for the classifier to combine with kind-denoting predicates is expected if classifiers are weak definite determiners.

Finally, Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009) argues that weak definites can sometimes have “covarying” uses, crucially when they are not preceded by an antecedent. This use of the weak definite can also be observed in Chuj, as seen in (15).

Under the most salient interpretation of (15), the (weak) definite description winh alkal ‘the mayor’ covaries with respect to each town Xun visited. That is, Xun spoke with the unique mayor of each town. As argued in detail in Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009), sections 3.2.2.3. and 4.3, and Jenks (Reference Jenks2018), a situation semantics account of weak definite articles like in (3) can capture such examples. The situation pronoun of the definite article can be bound by a quantifier over situations, such that the uniqueness presupposition is relativized to the situation variable that the universal quantifies over. This yields an interpretation paraphrasable as “in every situation s, Matin met the unique mayor in s”, with the uniqueness presupposition projecting universally.

Importantly, if the uniqueness presupposition is not met in each situation, then the use of a DP with a classifier is considered infelicitous:

In sum, we saw that noun classifiers pattern like weak definite articles. They presuppose, given a certain situation, that there is exactly one satisfier of the NP in that situation. We now turn to strong definites.

4. Decomposing strong definites in Chuj

In this section, we will see that strong definites, despite also requiring a noun classifier, are differentiated by their requirement for additional morphology. I will argue that this is because strong definites are compositionally derived from weak definite determiners in Chuj.

4.1 Strong definites in Chuj

Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009) lists the cases in (17) as environments requiring a strong definite. As we will see, all of these environments in Chuj require morphology in addition to the classifier: they must appear with a demonstrative.

(17) Subtypes of strong definites Footnote 11

1. Anaphoric uses of definites.

2. Covarying anaphoric definites (e.g., donkey sentences).

3. Producer-product bridging uses of definites.

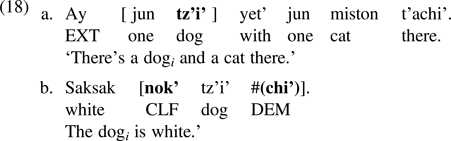

Full DPs (i.e., not pronouns, see section 5) whose referents have already been introduced in discourse generally require the addition of a demonstrative particle (glossed as DEM below), as shown by the possible continuation of (18a) in (18b). Note that Chuj features two demonstrative particles (distal chi’ and proximal tik), both of which can be used with deictic and anaphoric DPs.

In (18b), the noun classifier must obligatorily co-occur with the demonstrative chi’, since the referent of the nominal has already been introduced in the discourse.Footnote 12

It is widely agreed that strong forms of definite articles are also required in covarying anaphoric uses of full definite descriptions, such as donkey anaphora (Schwarz Reference Schwarz2009, Jenks Reference Jenks2018). Contrary to the covarying use of weak definites observed in the previous section (16), covarying anaphoric uses have an overt antecedent in the sentence. This is the case in donkey sentences, where the entity denoted by the donkey co-varies based on its owner.

(19) Every man who owns [ a donkey ]i loves [ thestrong donkey ]i.

Now consider a similar donkey sentence in Chuj, shown in (20). As can be observed, covarying anaphoric uses of definites require the presence of both a classifier and a demonstrative. That is, under a covarying reading in which every person hunted a different bird, the demonstrative cannot be felicitously omitted; in fact, omission of the demonstrative leads to an interpretation in which every person hunted the same bird.

Strong definites are also argued to arise with a subtype of “bridging definite” (Clark Reference Clark, Johnson-Laird and Wason1975), also known as “associative anaphora” (Hawkins Reference Hawkins1978) or “inferrables” (Prince Reference Prince and Cole1981). The kind of bridging definite that requires strong definites is the “producer-product bridging definite”. An English example is provided below.

In the above example, the author picks out the author of the book that was introduced in the previous sentence. As discussed in Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009), such definites require the strong article form. Consider now the following bridging definite in Chuj:

As demonstrated in (22), producer-product bridging definites in Chuj require the presence of both the classifier and the demonstrative, as expected if classifier–noun–demonstrative sequences form strong definites.

In sum, we have seen that Chuj demonstratives play a crucial role, together with noun classifiers, in deriving strong definites in the language. While weak definite environments involve a classifier, strong definite environments require both a classifier and a demonstrative.Footnote 14

Before moving on, it is worth further highlighting the clear similarities between Chuj and Mandarin: both derive strong definites with demonstratives. Crucially, however, the Chuj data suggest a departure from previous accounts of strong definites. Recall from above that in Jenks (Reference Jenks2018), there are two separate definite articles. One is ![]() $\iota$, a null definite determiner with the semantics of the weak definite. The other is the demonstrative, which incorporates the semantics of

$\iota$, a null definite determiner with the semantics of the weak definite. The other is the demonstrative, which incorporates the semantics of ![]() $\iota$ but adds an index argument. The Chuj data seem to indicate that strong definites can in fact be decomposed, an observation which I account for in the next subsection.

$\iota$ but adds an index argument. The Chuj data seem to indicate that strong definites can in fact be decomposed, an observation which I account for in the next subsection.

4.2 Building strong definites from weak definites

I propose that strong definites in Chuj are derived compositionally from two ingredients: (i) noun classifiers, which trigger a uniqueness presupposition, and (ii) demonstratives, which introduce an index that essentially imposes an anaphoricity condition. The account builds on Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009, Reference Schwarz2013, Reference Schwarz, Aguilar-Guevara, Loyo and Maldonado2019); Arkoh and Matthewson (Reference Arkoh and Matthewson2013); Jenks (Reference Jenks2018); and Hanink (Reference Hanink2018, Reference Hanink2020), but departs from these authors in two respects. First, while Reference SchwarzSchwarz, Reference Arkoh and MatthewsonArkoh and Matthewson, and Reference JenksJenks attribute the distinction between weak and strong definites to a lexical ambiguity, I argue, with Reference HaninkHanink, that the distinction is achieved compositionally. Second, the proposal differs from all previous accounts with regard to the resulting presupposition of strong definites: while uniqueness is evaluated with respect to the intersection of the NP predicate with the index-introducing argument in previous accounts, I propose that it is only evaluated with respect to the NP predicate in Chuj, and provide support for this choice in section 4.2.1.

As already discussed in the previous sections, I argue that Chuj noun classifiers have the denotation in (3), repeated as (23) for convenience. This denotation of the classifier accounts for all instances of weak definites seen in section 3.2, where a classifier appears alone with a nominal.

(23) Denotation of noun classifiers (= weak definite determiner)

⟦ CLF ⟧ = λs.λP 〈e,〈s,t〉〉:

$\exists$!x[P(x)(s)].

$\exists$!x[P(x)(s)]. $\iota$x[P(x)(s)]

$\iota$x[P(x)(s)]

In words, noun classifiers first take a situation pronoun as argument, and then combine with a predicate to yield an argument of type e, namely the unique satisfier of the NP in the situation. Accordingly, classifiers trigger the presupposition that there is only one satisfier of the predicate in the situation.

I propose that the sole contribution of demonstratives, then, is to introduce an “anaphoricity” (or “familiarity”) presupposition. The entry is provided in (24). The demonstrative denotes a partial identity function of type 〈e,e〉. In the presupposition, the demonstrative makes use of an index interpreted relative to a contextually provided assignment function.

(24)

$[\hskip-1pt[$ DEMi

$[\hskip-1pt[$ DEMi  $]\hskip-1pt]$g = λx: x = g(i). x

$]\hskip-1pt]$g = λx: x = g(i). x

To illustrate how strong definites are derived in Chuj, consider the structure and composition for the strong definite DP in (24). As shown, I assume that the noun first combines with the classifier, and that the demonstrative is then combined with the classifer–noun constituent.Footnote 15

In this derivation, the classifier nok’ first introduces a uniqueness presupposition (23), requiring that there be exactly one salient dog in s 1. If this presupposition is met, the classifier returns that entity. The second step is for the demonstrative to compose with the classifier–noun constituent. Given (24), the demonstrative bears an index, which must be in the domain of the variable assignment, and presupposes that its entity argument is identical to the value of this index (i.e., the ‘anaphoricity’ presupposition). I propose that for the relevant “dog” in (25) to be in the range of the assignment function, it must have either already been introduced in discourse, or be deictically identifiable. The condition thus captures non-deictic as well as deictic uses of demonstratives. If the anaphoricity presupposition (underlined in (26)) is met – namely if the relevant dog is picked out by the index 3 in the variable assignment – then the demonstrative chi’ composes with the unique salient dog in the situation, returning it as the referent of the DP. The overall result is a strong definite, realized compositionally by combining the weak definite semantics of the noun classifier in (23) with the semantics of the demonstrative in (24).Footnote 16

As an anonymous reviewer points out, the decompositional analysis just provided reveals an entailment relation between Chuj ‘weak’ and ‘strong’ definites. Uniqueness is still presupposed with strong definites (see (26)), and therefore ‘strong definiteness’ entails ‘weak definiteness’. That is, when the classifier appears with a noun by itself, it triggers a uniqueness presupposition, and when a demonstrative is added, the presupposition of the classifier survives and the demonstrative adds an additional anaphoricity presupposition. Assuming that the two constructions are ‘competitors’, then the obligatoriness of the demonstrative with strong definites in Chuj could be understood as an instance of Maximize Presupposition! (Heim Reference Heim, von Stechow and Wunderlich1991).

The next three subsections are divided as follows. I first discuss in section 4.2.1 a prediction regarding the scope of the quantifier introducing the uniqueness presupposition that follows from the decompositional account of noun classifiers just put forth, and which contrasts with the analysis provided in Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009), Arkoh and Matthewson (Reference Arkoh and Matthewson2013), Jenks (Reference Jenks2018) and Hanink (Reference Hanink2018), and I show that at least in Chuj, this prediction is borne out. I then discuss in section 4.2.2 an apparent exception to the appearance of demonstratives with strong definites, namely when strong definites appear inside a topicalized DP. Finally, I address in section 4.2.3 the fact that the proposed denotation for weak definite classifiers also encodes an existence presupposition, which Coppock and Beaver (Reference Coppock and Beaver2015) recently contest in relation to the definite article in English, and I argue that the issues discussed by Reference Coppock and BeaverCoppock and Beaver do not straightforwardly extend to Chuj.

4.2.1 The scope of uniqueness and deixis

The decompositional account of strong definites just proposed departs from the analysis of strong definites in previous work in one crucial respect. Recall that for these proposals, the index plays a role in the content of the uniqueness presupposition. Consider, again, Reference SchwarzSchwarz's entry for the strong definite in (27). A uniqueness presupposition is triggered for the intersection of the NP predicate with the index-introducing argument (where the index comes from a covert variable that saturates the third argument). The relevant segment is underlined for convenience.

(27) ⟦thestrong⟧ = λs r.λP.λy: ∃!x[P(x)(s r)

$\wedge$ x = y].

$\wedge$ x = y].  $\iota$x[P(x)(s r)

$\iota$x[P(x)(s r)  $\wedge$ x = y]

$\wedge$ x = y]

Within the presupposition of the strong definite article (underlined), the quantifier enforcing uniqueness (![]() $\exists$!) takes scope over the indexical argument (λy). This has important consequences for the content of the uniqueness presupposition: it will be satisfied when there is exactly one entity which is both a satisfier of the NP and identical to the index. This means that one could utter a strong definite description even if there is more than one salient satisfier of the NP predicate in the situation, since at most one entity will ever be identical to the index.

$\exists$!) takes scope over the indexical argument (λy). This has important consequences for the content of the uniqueness presupposition: it will be satisfied when there is exactly one entity which is both a satisfier of the NP and identical to the index. This means that one could utter a strong definite description even if there is more than one salient satisfier of the NP predicate in the situation, since at most one entity will ever be identical to the index.

Reference HaninkHanink's (Reference Hanink2018, Reference Hanink2020) decompositional account of strong definites in German and Washo makes the same prediction. For Reference HaninkHanink, the index-introducing argument, which she proposes denotes a property, first combines with the NP via Predicate Modification (Heim and Kratzer Reference Heim and Kratzer1998). The uniqueness presupposition is subsequently evaluated with respect to the result of this combination. Lexical entries and a relevant decomposition for the strong definite DP the dog are provided in (28).

As seen in the underlined part of (28c), the uniqueness presupposition of the weak definite article is again evaluated with respect to the intersection of the NP with the indexical property. Since g(3) will only ever pick out a single entity, the uniqueness presupposition can be met even if there is more than one dog in the context. The decompositional account I have proposed is slightly different. If the index is introduced outside of the uniqueness trigger, then the anaphoricity presupposition will be added on top of the presupposition that there is a unique satisfier of the NP in the situation, and so uniqueness in the situation should still hold. The presupposition in (26) is repeated as (28) for convenience:

(29) Presuppositions resulting from composition of nok’ tz'i’ chi’ in (25):

P:

$\exists$!x[x is a dog in s 1]

$\exists$!x[x is a dog in s 1]  $\wedge$ ɩx[x is a dog in s 1] = g(3)

$\wedge$ ɩx[x is a dog in s 1] = g(3)

This presupposition imposes the condition that there be a unique satisfier of the NP in s 1, a dog in this case, and that the unique dog of s 1 be identical to an entity in the range of the assignment function, namely g(3). Therefore, contrary to (27) and (28), the condition that there be one satisfier of the NP in the situation is maintained.

We might expect the result in (28) to have consequences for the felicity conditions of classifier–noun–demonstrative constructions, especially when used deictically. That is, it might be infelicitous to utter (24) if there is more than one dog.Footnote 17 Though more work is needed to properly understand deictic uses of demonstratives in Chuj, preliminary investigation suggests that this prediction is, at least partially, borne out.

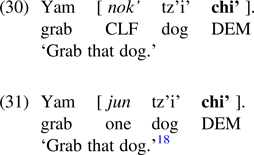

There are at least two ways demonstratives can be used for deixis in Chuj:

While the noun and the demonstrative co-occur with a classifier in (30), they co-occur with the numeral jun ‘one’ in (31). While it is acceptable to utter both of these sentences in a context where there is only one dog, the speakers I have consulted indicate a clear preference for (30) if the context contains more than one dog (32b). That is, an imperative like (30) is judged perfectly acceptable in a setting like (32a), but less so in a setting like (32b). The sentence in (31) without a noun classifier, on the other hand, is judged equally felicitous in both settings in (32).Footnote 19

(32)

The fact that (30) is dispreferred by speakers in a context where there is more than one dog supports the decomposition proposed in this article: classifiers impose a uniqueness presupposition on top of which the demonstrative adds an anaphoricity condition. We should therefore expect to see the effects of the uniqueness presupposition in classifier–noun–demonstrative constructions when there is more than one satisfier of the NP, as seems to be the case.

It should be noted, though, that the judgments are not categorical, and that there is considerable speaker variability. In particular, of the three speakers I have been able to consult on this datapoint, one judged (30) as infelicitous in (32b), whereas two judged it as more or less acceptable. Crucially though, all indicated a clear preference for (32b) in this setting. It is important to note that this kind of variability is not entirely unexpected given a situation semantics approach to definiteness. That is, the uniqueness presupposition is evaluated with respect to the situation picked out by the situation variable, which does the domain restriction (Schwarz Reference Schwarz2009). If the situation variable is set, for instance, as the entire utterance situation, a failure of the uniqueness presupposition is expected. On the other hand, speakers may sometimes be willing to admit a more ‘minimal’ value for the situation variable (e.g., one in which only the dog that is being pointed at is considered, and the other dogs are discarded). In that case, it would be possible for the uniqueness presupposition to hold even if there are several dogs in the larger utterance context. Exactly how domain restriction should be constrained is not an issue I can address in this article (see also footnote 7). However, the essential point for our concerns is that if the classifier takes scope below the demonstrative, as proposed here, then we should sometimes perceive the effects of the uniqueness presupposition, as is observed in the dispreference for (30) in a context with more than one dog.

In sum, though this subsection has presented some evidence that situational uniqueness must hold for strong definites with demonstratives in Chuj, it does not have to be the case that all strong definites across languages are so construed. In fact, in section 5, I will claim that contrary to strong definites with overt NPs, anaphoric uses of pronouns involve an indexical argument that applies in the scope of the uniqueness trigger, yielding a result equivalent to the denotations for strong definites provided in previous work.

4.2.2 Strong definites and topichood

There is an exception to to the generalization that demonstratives are needed for strong definites: when a Chuj DP is topicalized, the demonstrative is optional. Chuj topics tend to appear at the left periphery (with the topic marker ha), and they obligatorily corefer with a resumptive pronoun in the main clause (Bielig Reference Bielig2015, Royer Reference Royer, Caponigro, Torrence and Maldonado2021). This is shown in (33b), which could naturally follow the utterance in (18a), repeated here as (33a).

I tentatively propose that topicalized projections involve a topic head that introduces a presupposition requiring the referent of the DP to be discourse-old, and that this circumvents the need for an additional demonstrative. Topicalized constituents are cross-linguistically associated with discourse-old referents (see, e.g., Prince Reference Prince, Mann and Thompson1992, von Fintel Reference von Fintel1994, and Aissen Reference Aissen1992 on Mayan). If only constituents whose referent is discourse-old can be topics in Chuj, then it follows that topicalized constituents will always be anaphoric, even without a demonstrative. Interestingly, Mandarin exhibits the same exception with strong definites – demonstratives are optional with topicalized DPs (Jenks Reference Jenks2018, Section 5.3) – suggesting that this may be a general property of strong definites across languages.Footnote 20 I leave a detailed analysis for future work.

4.2.3 Do classifiers also presuppose existence?

In recent work, Coppock and Beaver (Reference Coppock and Beaver2015) argue that the English definite determiner does not encode an existence presupposition, a presupposition it has commonly been associated with since at least Frege Reference Frege, Geach and Black1892. They offer a denotation along the lines of (34).

(34) ⟦ the ⟧ = λP: |P| ≤ 1. λx. P(x)

Under this denotation, the definite determiner combines with NP predicates to yield a predicative meaning – the dog denotes the predicate of being a dog, defined only if there is one or less than one dog in the context. In other words, Reference Coppock and BeaverCoppock and Beaver take predicative uses of definite articles, as in (35), to be their most basic use. This is in opposition to the denotation proposed here, as well as in Schwarz Reference Schwarz2009 and subsequent work, where the definite determiner is understood to (i) yield an entity (rather than a predicate), and (ii) trigger an existence presupposition.

As Reference Coppock and BeaverCoppock and Beaver note, the absence of an existence presupposition is especially supported in examples like (35a). For them, only author of Waverley denotes a predicate which holds of an entity if and only if that entity and no other is an author of Waverley. But under its most salient interpretation, (35a) conveys that Scott is one of at least two authors of Waverley, in which case there is no satisfier of only author of Waverley. Since the sentence is felicitous, they conclude that the should not presuppose existence. To account for argumental type e definites, Reference Coppock and BeaverCoppock and Beaver propose two type-shifts based on Partee Reference Partee, Groenendijk, Jongh and Stokhof1986 (IOTA and EX), which together type-shift the-predicates to type e arguments (IOTA) or existential quantifiers (EX).

It is not clear, however, that this analysis of the definite article naturally extends to Chuj classifiers. One reason is that Chuj classifier–noun constructions are categorically banned from surfacing as predicates (this has also been noted by Craig Reference Craig1986 for Popti’ and by Zavala Reference Zavala1992, Reference Zavala and Senft2000 for Akatek). This is shown in (36).

The inability of classifier–noun constructions to appear in predicative positions is clearly a challenge for any analysis that would attempt to treat them as predicative in their most basic use.

Moreover, the morpheme usually used to convey the meaning of only in Chuj, nhej, is not compatible with predicative nominals (regardless of the presence of a classifier), as opposed to the English example in (35a).Footnote 21 This means that it is impossible to test utterances like English (35a) in Chuj, and therefore it is impossible to verify the key evidence presented in Coppock and Beaver (Reference Coppock and Beaver2015) against an analysis of definite determiners as presupposing existence.

In sum, though a predicative analysis of noun classifiers along the lines of Reference Coppock and BeaverCoppock and Beaver's account of the definite article in English could in principle be adapted to account for the distribution of noun classifiers in Chuj, we saw that classifier–noun configurations cannot be used predicatively. This casts doubt on treating classifier DPs as basically predicative. Moreover, Reference Coppock and BeaverCoppock and Beaver provide evidence from examples like (35a) that English the should not also presuppose existence. In Chuj, however, configurations like (35a), where only appears under the scope of negation, are simply ineffable. I conclude that there is no reason to remove the existence presupposition from noun classifiers, and therefore maintain the denotation of classifiers as in (3) and (23).

4.2.4 Summary

I have proposed a decompositional account of strong definites in Chuj. While noun classifiers introduce a uniqueness (and existence) presupposition, demonstratives contribute an anaphoricity presupposition, namely that the entity output by the weak definite classifier is in the range of the assignment function. In the next section, we turn to an apparent problem for this account: the fact that classifiers can appear alone, and crucially without demonstratives, as anaphoric pronouns. I provide a solution, which essentially proposes a view of pronouns as concealed definite descriptions (Postal Reference Postal1966; Evans Reference Evans1977; Cooper Reference Cooper, Henry and Schnelle1979; Heim Reference Heim1990; Elbourne Reference Elbourne2005, Reference Elbourne2013, among many others). Building on Cooper (Reference Cooper1983) and Heim (Reference Heim1990), I assume that classifier uses of anaphoric pronouns are definite determiners that combine with a null predicative variable, which also serves to introduce an index. In that sense, classifier pronouns are conceived of as just another kind of strong definite. However, they also differ from the strong definites with demonstratives discussed in this section, in that the index argument is introduced below the classifier, yielding a strong definite with the same scopal properties as the ones in work like Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2009), Arkoh and Matthewson (Reference Arkoh and Matthewson2013), Jenks (Reference Jenks2018), and Hanink (Reference Hanink2018, Reference Hanink2020).

5. Decomposing pronouns

Mayan languages are generally robustly pro-drop (Coon Reference Coon2016; Aissen et al. Reference Aissen, England, Maldonado, Aissen, England and Maldonado2017). However, Q'anjob’alan languages are an exception, since noun classifiers serve as third person pronouns (henceforth “classifier pronouns”), and under most circumstances cannot be dropped. Consider (38).

In the above example, there are two sentences. In the first, an indefinite jun tz'i’ ‘a dog’ introduces a new referent into the discourse. In the second, the use of the classifier nok’ alone is sufficient to refer back to the dog that was introduced in the previous sentence.

The example in (38) is somewhat surprising given the proposal from the previous section that strong definites in Chuj can be decomposed. That is, if classifiers introduce only a uniqueness presupposition (and not an anaphoricity presupposition), then why can they surface alone as anaphoric pronouns? Perhaps even more surprising is the fact that the classifier pronoun in (38) cannot co-occur with a demonstrative, even when used anaphorically:Footnote 22

This starkly contrasts with anaphoric uses of classifiers with overt nominals, which, as shown in examples like (18), require the presence of a demonstrative.

Another important observation concerns the use of classifier pronouns in donkey sentences:

Again, the absence of a demonstrative in (40) is surprising given the fact that anaphoric uses of definite descriptions in donkey sentences with overt nominals usually require one, as illustrated in (20) above).Footnote 23

If we want to maintain the semantics of noun classifiers as weak definite determiners, as proposed in (3), two questions must be addressed: (i) why can noun classifiers appear alone as anaphoric pronouns? and (ii) how is anaphoricity encoded, if not with a demonstrative? In what follows, I address these questions.

5.1 Pronouns as definite descriptions

Since Postal (Reference Postal1966), many syntactic and semantic analyses of pronouns, or at least a subtype of what have been referred to as pronouns, posit that they are actually definite determiners with null or elided NPs (e.g., Cooper Reference Cooper, Henry and Schnelle1979, Abney Reference Abney1987, Heim Reference Heim1990, Ritter Reference Ritter1995, Déchaine and Wiltschko Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002, Elbourne Reference Elbourne2005, Arkoh and Matthewson Reference Arkoh and Matthewson2013, Clem Reference Clem, Lamont and Tetzloff2017, Patel-Grosz and Grosz Reference Patel-Grosz and Grosz2017, Reference Bi, Jenks, Espinal, Castroviejo, Leonetti, McNally and Real-PuigdollersBi and Jenks Reference Bi, Jenks, Espinal, Castroviejo, Leonetti, McNally and Real-Puigdollers2019). There are many reasons to support this view. For one, pronominal elements and determiners often look alike (German examples are from Elbourne Reference Elbourne2001):

Furthermore, it has long been observed that pronouns tend to share more with determiners than they do with nouns in their distribution (Postal Reference Postal1966, Abney Reference Abney1987). A classic example comes from first and second person pronouns in English, which pattern like determiners, and unlike nouns, in admitting an overt noun (Postal Reference Postal1966).

(43) we (linguists), you (people), you (liar), them (artists)…

Finally, pronouns and definite determiners often show similar effects, notably in cases of donkey anaphora like (44) (Heim Reference Heim1990, Elbourne Reference Elbourne2005); also compare the Chuj examples in (20) and (40) above.

(44) Every person who owns a donkey loves it / the donkey.

At least two types of accounts have been proposed to explain the similarity between pronouns and definite descriptions. On the one hand, Elbourne (Reference Elbourne2013) proposes that the only difference between full DPs and pronouns is NP-deletion. In other words, the and pronouns such as it, she, and he exhibit identical semantics. The contrast between articles and pronouns lies solely in the phonology: while the appears before overt NPs, the pronominal forms appear before elided NP complements:

Another strategy has been to assume that pronouns are definite determiners that combine with special unpronounced morphology, and which must critically involve an index interpreted relative to the assignment function (see, e.g., Cooper Reference Cooper, Henry and Schnelle1979; Heim Reference Heim1990; Elbourne Reference Elbourne2001, Reference Elbourne2005). For such theories, pronouns in English are also considered as morphophonological variants of the definite article:

Interestingly, the Chuj data appear to favour one of these two accounts. Recall from (39) that classifier pronouns do not generally co-occur with demonstratives, which obligatorily appear with strong definites in Chuj. All else being equal, an NP-deletion account of pronouns (e.g., Elbourne Reference Elbourne2013) would therefore predict that anaphoric classifier pronouns always appear with demonstratives. That is, if pronominal uses of classifiers were identical to determiner uses of classifiers, except for deletion of the NP in the phonology, then we would expect that both would require a demonstrative when used anaphorically. However, as already seen in (39), this prediction is not borne out. An analysis with a covert index, on the other hand, offers a straightforward account of the absence of demonstratives with anaphoric pronouns. Under such accounts, weak definite articles combine with a null variable, which introduces an index. This means that adding an index-introducing demonstrative would have no further effect – it would render the demonstrative's contribution vacuous. To the extent that the introduction of trivial presuppositions is not tolerated, given basic conversational principles such as the Maxim of Manner (Grice Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975), we do not generally expect demonstratives to occur with classifier pronouns. Alternatively, the absence of the demonstrative with classifier pronouns could also be explained given general structural economy constraints on the addition of redundant structure, in line with Cardinaletti and Starke (Reference Cardinaletti, Starke and van Riemsdijk1999), Schlenker (Reference Schlenker2005), Patel-Grosz and Grosz (Reference Patel-Grosz and Grosz2017).

I therefore propose that anaphoric uses of classifier pronouns involve a null predicative variable, provided in (49), whose sole contribution is to introduce an index. Since this index can presumably be bound, it is possible to account for the use of classifier pronouns in donkey sentences (see (40)).

(49) ⟦ pro i ⟧g = λx. x = g(i)

Classifier pronouns are thus E-type pronouns in essence, and denote the unique entity identical to a contextually-determined entity in the range of the assignment function, as in (50).

(50) ⟦ ⟦ CLF s 1 ] pro i ] ⟧ g =

$\exists$!x[x = g(3) in s 1].

$\exists$!x[x = g(3) in s 1].  $\iota$x[x = g(3) in s 1]

$\iota$x[x = g(3) in s 1]

As suggested by an anonymous reviewer, there may be a second empirical reason to favour an E-type approach to classifier pronouns like the one illustrated in (50). If only NP-deletion were at issue, we might expect pronouns to always trigger a uniqueness presupposition, and we would expect sentences like (51) to be infelicitous, since there is clearly no unique elder woman in the context in (51). This prediction is not borne out; (51) is judged felicitous by speakers.

An E-type approach, on the other hand, does not make this prediction. Since there will always be at most one entity that is identical to any given index, the uniqueness presupposition in (50) can be met, even if there are several elder women in the situation. This means that the use of an (E-type) classifier pronoun in Chuj should be possible in sentences similar to (50), as is indeed the case.

In sum, we now have answers to the questions set out at the end of the previous subsection: (i) why can noun classifiers be used alone as anaphoric pronouns? and (ii) how is anaphoricity introduced, if not with a demonstrative?

Regarding (i), I showed that it was possible to keep with the weak definite semantics of classifiers in (3) if classifiers combine with a null predicative variable, as independently proposed for E-type pronouns by Cooper (Reference Cooper, Henry and Schnelle1979) and Heim (Reference Heim1990). This theory of pronoun formation relies on the widely-held assumption that pronouns are concealed definite descriptions, an assumption that is especially compelling for Chuj, since pronouns and determiner uses of classifiers exhibit no allomorphic variation (unlike determiners and pronouns in, say, English).

Regarding (ii), I argued that in their use as pronouns, classifiers can combine with a null index-introducing variable, thereby bleeding the need for an independent index-introducing demonstrative (possibly due to structural economy constraints). However, I proposed that with classifier pronouns, the anaphoricity presupposition is introduced below the uniqueness trigger, revealing a denotation for the strong definite that is slightly different to the one that results from the composition of classifier–noun–demonstrative constructions, where the anaphoricity presupposition is evaluated on top of the uniqueness presupposition (compare (50) with (29)). This denotation for anaphoric classifier pronouns can therefore be seen as an alternative compositional path to strong definiteness in Chuj, one which aligns more closely with the proposed denotations for the strong definite article in previous work.

Finally, the proposal has implications for theories of pronouns that view them as (weak) definite descriptions with elided NPs (e.g., Elbourne Reference Elbourne2013). That is, I showed that this view of anaphoric pronouns would make a wrong prediction for sentences like (51) in Chuj, and that anaphoric pronouns were better understood as determiners which combine with covert index-introducing predicates.

5.2 Are there weak definite pronouns?

I have just proposed that, as weak definite determiners, noun classifiers can combine with a covert index-introducing predicate to yield an E-type pronoun. This accounts for most pronominal cases of classifiers, since classifier pronouns tend to be anaphoric. However, given that classifiers are weak definites, it is interesting to consider whether they could also be used non-anaphorically, or in other words as “weak definite pronouns”. In this subsection, I show that classifier pronouns can sometimes behave as weak definites, and propose that it is only in such cases that Chuj pronouns are truly definite determiners with elided NPs, as proposed more generally for pronouns by Elbourne (Reference Elbourne2013).

The idea that the pronominal system of a language might be influenced by its determiner system is not new. This hypothesis is put forth by Matthewson (Reference Matthewson, Friedman and Ito2008), who states that “perhaps in general, the semantics of third-person pronouns in a language L is based on the semantics of determiners in L”. More recently, Bi and Jenks (Reference Bi, Jenks, Espinal, Castroviejo, Leonetti, McNally and Real-Puigdollers2019), building on work by Patel-Grosz and Grosz (Reference Patel-Grosz and Grosz2017) on German, and Clem (Reference Clem, Lamont and Tetzloff2017) on Tswefap, explicitly argue that a language's pronominal inventory should be isomorphic to its determiners, proposing the following generalization:

To support this generalization, Bi and Jenks (Reference Bi, Jenks, Espinal, Castroviejo, Leonetti, McNally and Real-Puigdollers2019) argue that Mandarin, which, recall from section 3.1, marks the distinction between weak and strong definites, also marks it in its pronominal system, as shown in Table 4. As summarized in the table below, while “weak definite pronouns” are entirely covert and combine with ![]() $\iota$, “strong definite pronouns” tend to require a demonstrative.Footnote 24 Note that Reference Bi, Jenks, Espinal, Castroviejo, Leonetti, McNally and Real-PuigdollersBi and Jenks follow Elbourne (Reference Elbourne2005) in assuming that pronouns involve elided NPs.

$\iota$, “strong definite pronouns” tend to require a demonstrative.Footnote 24 Note that Reference Bi, Jenks, Espinal, Castroviejo, Leonetti, McNally and Real-PuigdollersBi and Jenks follow Elbourne (Reference Elbourne2005) in assuming that pronouns involve elided NPs.

Table 4: Determiner/pronoun configurations in Mandarin discussed in Reference Bi, Jenks, Espinal, Castroviejo, Leonetti, McNally and Real-PuigdollersBi and Jenks Reference Bi, Jenks, Espinal, Castroviejo, Leonetti, McNally and Real-Puigdollers2019

Reference Bi, Jenks, Espinal, Castroviejo, Leonetti, McNally and Real-PuigdollersBi and Jenks establish a number of tests to contrast weak definite from strong definite pronouns. One proposed environment for weak definite pronouns is anaphora to indefinites under the scope of negation within a conditional or disjunction, or so-called “bathroom sentences” (Roberts Reference Roberts1989, due to Barbara Partee):

(53) Either the building does not have [ a bathroom ]i, or iti is in a funny place.

Since the most salient (and perhaps only) interpretation of (53) is one in which the indefinite a bathroom appears under the scope of negation, there is no entity that satisfies the property of being a bathroom in the first conjunct of (53). This means that there is no individual in the discourse that can get picked up by the assignment function, and so it must be a weak definite in (53). As corroborated by Reference Bi, Jenks, Espinal, Castroviejo, Leonetti, McNally and Real-PuigdollersBi and Jenks (their examples (12) and (13)), demonstrative pronouns are expectedly infelicitous in Mandarin “bathroom sentences”, and a null pronoun must instead be used.

In Chuj, noun classifiers can appear as pronouns in “bathroom sentences”:

As seen above, the classifier pronoun k'en can be used even though it has no antecedent in the discourse. This suggests that classifier pronouns can be weak definites, a welcome result if classifiers encode weak definiteness.

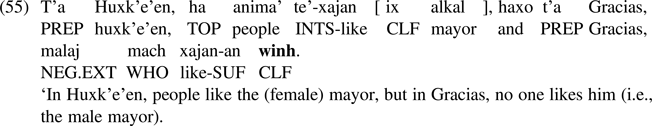

Reference Bi, Jenks, Espinal, Castroviejo, Leonetti, McNally and Real-PuigdollersBi and Jenks also show that weak (null) pronouns in Mandarin are forced in cases of situation-dependent covariation or so-called “president sentences” (Evans Reference Evans1977). Consider the following example:

In (55), the use of the pronoun winh has again no clear antecedent (i.e., the unique (female) mayor of Huxk'e’en is not also the unique (male) mayor of Gracias). Since Chuj classifier pronouns are allowed in such sentences, we are again led to conclude that classifier pronouns can sometimes track weak definites.

The examples in (54) and (55) ultimately suggest that there must be more than one type of classifier pronoun in Chuj. Classifier pronouns cannot always involve a null index-introducing predicate, as was proposed for classifier pronouns in section 5.1, since in the weak definite uses of pronouns seen in (54) and (55), the assignment function cannot supply a value for the index that would be required by strong definite pronouns. Therefore, I propose that weak uses of classifier pronouns instantiate cases of definite determiners with elided NPs in Chuj. As such, while strong uses of classifier pronouns in Chuj involve a classifier with a null predicate that introduces an index, weak uses involve an elided NP:

(56) (At least) two kinds of pronouns in Chuj:

a. CLF + g(i) = strong pronoun

b. CLF + NP = weak pronoun

It should be acknowledged that if configurations like (56b) are sometimes possible for ‘weak’ pronouns, it is mysterious why [CLF + NP + DEM] configurations are not also generally possible to form ‘strong’ pronouns (see (39) above). I tentatively propose that the preference for (56a) results from structural economy constraints, as proposed for similar phenomena by Cardinaletti and Starke (Reference Cardinaletti, Starke and van Riemsdijk1999), Schlenker (Reference Schlenker2005), Katzir (Reference Katzir2011), and Patel-Grosz and Grosz (Reference Patel-Grosz and Grosz2017). Concretely, since [CLF + g(i)] is structurally less complex than [CLF + NP + DEM], the former is favoured. Note, though, that classifier pronouns do sometimes exceptionally co-occur with demonstratives (see footnote 22), most commonly when topicalized or focused. Though I have decided to set this observation aside here, it could very well be that the structural economy constraint can sometimes be lifted.

To summarize, I have extended the generalization proposed by Reference Bi, Jenks, Espinal, Castroviejo, Leonetti, McNally and Real-PuigdollersBi and Jenks in (52) to Chuj. Though I have argued that the generalization is formally correct for Chuj – since there are two kinds of pronouns – the distinction between weak and strong definites is not overtly reflected in Chuj's pronominal system. The conclusion that emerges is that languages that overtly distinguish weak and strong definites in their determiner system will not necessarily make this distinction overtly in their pronominal system.

6. Conclusions and cross-linguistic implications

In this article, I have proposed a decompositional account of definiteness and pronoun formation in Chuj. At the heart of all of the constructions we observed were noun classifiers. I argued that noun classifiers are best characterized as weak definite determiners: they trigger the presupposition that there is a unique satisfier of the NP in a situation. I then argued that strong definites (including anaphoric pronouns) are derived compositionally, by combining the weak definite semantics of noun classifiers with additional overt (or covert) morphemes signalling anaphoricity. Overall, while weak definites are always realized by combining a classifier with an NP, there are at least three strategies to obtain strong definiteness, summarized in Table 5.

Table 5: Classifier configurations

As discussed in section 5, the account has implications for theories of pronoun formation. Based on previous work on the distinction between weak definite pronouns and strong definite pronouns (Clem Reference Clem, Lamont and Tetzloff2017, Patel-Grosz and Grosz Reference Patel-Grosz and Grosz2017, and Bi and Jenks Reference Bi, Jenks, Espinal, Castroviejo, Leonetti, McNally and Real-Puigdollers2019), I argued that there are two kinds of pronominal constructions in Chuj, which together reflect the distinction between weak and strong definites. I proposed that while anaphoric pronouns combine with covert index-introducing predicates to form E-type pronouns, weak definite uses of classifier pronouns involve NP ellipsis, and thus lack an index.

Finally, I suggested that the index responsible for introducing the anaphoricity presupposition with strong definites can vary across languages as to where it is evaluated with respect to the uniqueness trigger. Specifically, the index is introduced at a wide-scope position above the uniqueness trigger in classifier–noun–demonstrative constructions, but below the uniqueness trigger with anaphoric pronouns. This could be a general point of cross-linguistic variation, and so “strong definites” might be expected to differ slightly in their presuppositions from language to language.

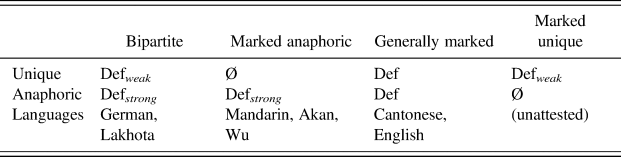

One question for future work concerns the extent to which strong definites are crosslinguistically decomposable. As already discussed in section 4, the compositional nature of strong definites observed for Chuj is not straightforwardly captured in previous proposals, including the recent typology of definiteness marking in Jenks (Reference Jenks2018), reproduced in Table 6.

Table 6: Typology of definiteness marking (Jenks Reference Jenks2018)

In this typology, bipartite languages overtly and distinctively mark the contrast between weak and strong definites; marked anaphoric languages only overtly mark strong definites, but not weak definites; generally marked languages overtly mark definiteness, but do not make a distinction between weak and strong definites; and marked unique languages would correspond to the other logical but unattested possibility: languages that mark weak definites, but not strong definites.

Crucially, under this typology of definiteness marking, weak and strong definite determiners are conceived of as separate lexical items. At first glance, Chuj appears to fit as a bipartite language insofar as it overtly and distinctively marks the distinction between weak and strong definites. However, the distribution of weak and strong definites in Chuj points toward another type of language: one that marks the distinction compositionally, as argued in section 4.2, as opposed to marking the distinction via the use of separate lexical items.

Taking this observation one step further, the distribution of Chuj definites opens up the possibility that the distinction between weak and strong definites is always compositional, as also proposed in Hanink (Reference Hanink2018, Reference Hanink2020) for German and Washo. If this is the case, the account of weak and strong definites in Jenks (Reference Jenks2018) for Mandarin requires minimal modification: ![]() $\iota$ could derive the uniqueness presupposition for both weak and strong definites, and the Mandarin demonstrative's sole contribution, then, would be to introduce an anaphoricity presupposition.

$\iota$ could derive the uniqueness presupposition for both weak and strong definites, and the Mandarin demonstrative's sole contribution, then, would be to introduce an anaphoricity presupposition.

Since weak definite articles are not overtly realized in Mandarin, it is not immediately obvious whether we should favour the current proposal, extended to Mandarin, or the proposal in Jenks (Reference Jenks2018), which derives the distinction via separate lexical items. However, since weak and strong definites share a common core – they both presuppose uniqueness – a decompositional account seems inviting. A lexical-ambiguity theory renders the common core accidental – ![]() $\iota$ and the demonstrative independently encode uniqueness. A decompositional account, on the other hand, depends on it directly –

$\iota$ and the demonstrative independently encode uniqueness. A decompositional account, on the other hand, depends on it directly – ![]() $\iota$ is responsible for deriving the uniqueness presupposition with both weak and strong definites. And if the current proposal is adopted, the parallel with Chuj and Mandarin becomes clear: while both Chuj and Mandarin overtly realize the anaphoricity presupposition of strong definites with a demonstrative, the uniqueness presupposition is achieved overtly with classifiers in Chuj, but covertly with

$\iota$ is responsible for deriving the uniqueness presupposition with both weak and strong definites. And if the current proposal is adopted, the parallel with Chuj and Mandarin becomes clear: while both Chuj and Mandarin overtly realize the anaphoricity presupposition of strong definites with a demonstrative, the uniqueness presupposition is achieved overtly with classifiers in Chuj, but covertly with ![]() $\iota$ in Mandarin (note again that whether the index appears under or over the unique existential quantifier could potentially vary across languages).

$\iota$ in Mandarin (note again that whether the index appears under or over the unique existential quantifier could potentially vary across languages).

There is, moreover, a typological reason to favour decompositional analyses, a point on which I conclude. As highlighted in Jenks (Reference Jenks2018) and in Table 6, there is a gap in the typology of definite determiners: no language only marks weak definites. While lexical-ambiguity theories do not straightforwardly predict this gap, decompositional accounts do.Footnote 25 That is, languages which only have definite determiners that trigger uniqueness presuppositions will always come out as “generally marked”, since weak definiteness is just one piece in the composition of strong definites.